Miriam Soljak on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Miriam Bridelia Soljak (; 15 June 1879 – 28 March 1971) was a pioneering New Zealand

New Zealand's first nationality law, the Aliens Act of 1866, specified that foreign women who married New Zealanders automatically acquired the nationality of the husband. It applied only to the wives of

New Zealand's first nationality law, the Aliens Act of 1866, specified that foreign women who married New Zealanders automatically acquired the nationality of the husband. It applied only to the wives of

From 1926, Soljak worked on women's issues. She fought for women to receive

From 1926, Soljak worked on women's issues. She fought for women to receive  Soljak joined the New Zealand Rationalist Association in 1940 and in 1941 was elected to serve on the executive committee. The organisation protested the government's treatment of

Soljak joined the New Zealand Rationalist Association in 1940 and in 1941 was elected to serve on the executive committee. The organisation protested the government's treatment of

feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

, communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, unemployed rights activist and supporter of family planning

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marita ...

efforts. Born in Thames, New Zealand

Thames () ( mi, Pārāwai) is a town at the southwestern end of the Coromandel Peninsula in New Zealand's North Island. It is located on the Firth of Thames close to the mouth of the Waihou River. The town is the seat of the Thames-Coromandel (di ...

, she was raised as a Catholic and studied to be a teacher. From 1898 to 1912, she taught in native schools, learning about Māori culture

Māori culture () is the customs, cultural practices, and beliefs of the indigenous Māori people of New Zealand. It originated from, and is still part of, Polynesians, Eastern Polynesian culture. Māori culture forms a distinctive part of Cul ...

and becoming fluent in the language. In 1908, she married Peter Soljak, an immigrant from Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

, now part of Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

, but at the time part of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

. In 1919, because of war legislation, she was denaturalised

Denaturalization is the loss of citizenship against the will of the person concerned. Denaturalization is often applied to ethnic minorities and political dissidents. Denaturalization can be a penalty for actions considered criminal by the state ...

and forced to register as an enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

, because of her marriage. Despite their divorce in 1939, Soljak was unable to recover her British nationality.

In protest, Soljak led a campaign that lasted for nearly thirty years for women to have their own individual nationality in New Zealand. She was involved in health issues which included child welfare, family planning and contraception, infant and maternal mortality, and sex education. Economic concerns such as mother's endowments, pensions for elders and the infirm, unemployment compensation for women, as well as policies that assisted homeless women, widows, and separated women were also a focus of Soljak's work. She also strove to support indigenous communities, becoming involved in the protection of Māori women and girls and Samoan independence movement, though she was a pacifist. In 1946, New Zealand amended the nationality law

Nationality law is the law of a sovereign state, and of each of its jurisdictions, that defines the legal manner in which a national identity is acquired and how it may be lost. In international law, the legal means to acquire nationality and for ...

, changing the policy that a woman automatically acquired her husband's nationality upon marriage.

Early life and education

Miriam Bridelia Cummings was born on 15 June 1879 in Thames to Annie () and Matthew Cummings. Her mother was of Scottish heritage and her father, a carpenter, was from Ireland. There were eight siblings in the family and because of their parents' religious differences, the boys were raised as Protestant and the girls as Catholic. Cummings attended school in Thames andNew Plymouth

New Plymouth ( mi, Ngāmotu) is the major city of the Taranaki region on the west coast of the North Island of New Zealand. It is named after the English city of Plymouth, Devon from where the first English settlers to New Plymouth migrated. ...

for her high school education. In 1896, she entered the pupil-teacher

Pupil teacher was a training program in wide use before the twentieth century, as an apprentice system for teachers. With the emergence in the beginning of the nineteenth century of education for the masses, demand for teachers increased. By 1840, ...

programme at New Plymouth Central School and finished her apprenticeship at Kauaeranga School in Thames.

Teaching (1898–1919)

In 1898, Cummings took up a teaching post at Taumarere Native School in Northland. Moving to Pukaru (also shown as Pakaru), near Kawakawa, she lived with a Māori family and taught at the native school. Cummings became very interested in theMāori culture

Māori culture () is the customs, cultural practices, and beliefs of the indigenous Māori people of New Zealand. It originated from, and is still part of, Polynesians, Eastern Polynesian culture. Māori culture forms a distinctive part of Cul ...

and the welfare of the Ngāpuhi

Ngāpuhi (or Ngā Puhi) is a Māori iwi associated with the Northland region of New Zealand and centred in the Hokianga, the Bay of Islands, and Whangārei.

According to the 2018 New Zealand census, the estimated population of Ngāpuhi is 165, ...

Maori communities in that area. She became fluent in the Māori language

Māori (), or ('the Māori language'), also known as ('the language'), is an Eastern Polynesian language spoken by the Māori people, the indigenous population of mainland New Zealand. Closely related to Cook Islands Māori, Tuamotuan, and ...

. She left the area and in 1905 had a daughter, Dorothea Grace, in Auckland. Moving to Rotorua

Rotorua () is a city in the Bay of Plenty region of New Zealand's North Island. The city lies on the southern shores of Lake Rotorua, from which it takes its name. It is the seat of the Rotorua Lakes District, a territorial authority encompass ...

, she worked as a domestic in private homes until 10 June 1908, when she married Peter Soljak. He was an immigrant from Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; hr, Dalmacija ; it, Dalmazia; see #Name, names in other languages) is one of the four historical region, historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a narrow belt of the east shore of ...

, at the time part of the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

, who had little education or fluency in English, but was prepared to work at various jobs to support the family. He had left his homeland to avoid conscription into the Austrian army and strongly opposed Austrian rule in Dalmatia. At one time he worked as a gumdigger and at the time of their marriage, was a restaurateur.

Resuming her teaching at Pukaru in 1910, Soljak was provided with nursery care for her children because of her skill working with Māori students. Peter worked nearby in Kawakawa building a bridge. When Soljak gave birth to her fourth child in 1912, she left teaching and the family moved to Tauranga

Tauranga () is a coastal city in the Bay of Plenty region and the fifth most populous city of New Zealand, with an urban population of , or roughly 3% of the national population. It was settled by Māori late in the 13th century, colonised by ...

, where Peter worked on various construction and transport projects. They struggled financially and moved often. Soon after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

ended, when her seventh child, Paul, was born in 1919, Soljak was refused a bed in the maternity home and told it was because she was an enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

and had forfeited her nationality

Nationality is a legal identification of a person in international law, establishing the person as a subject, a ''national'', of a sovereign state. It affords the state jurisdiction over the person and affords the person the protection of the ...

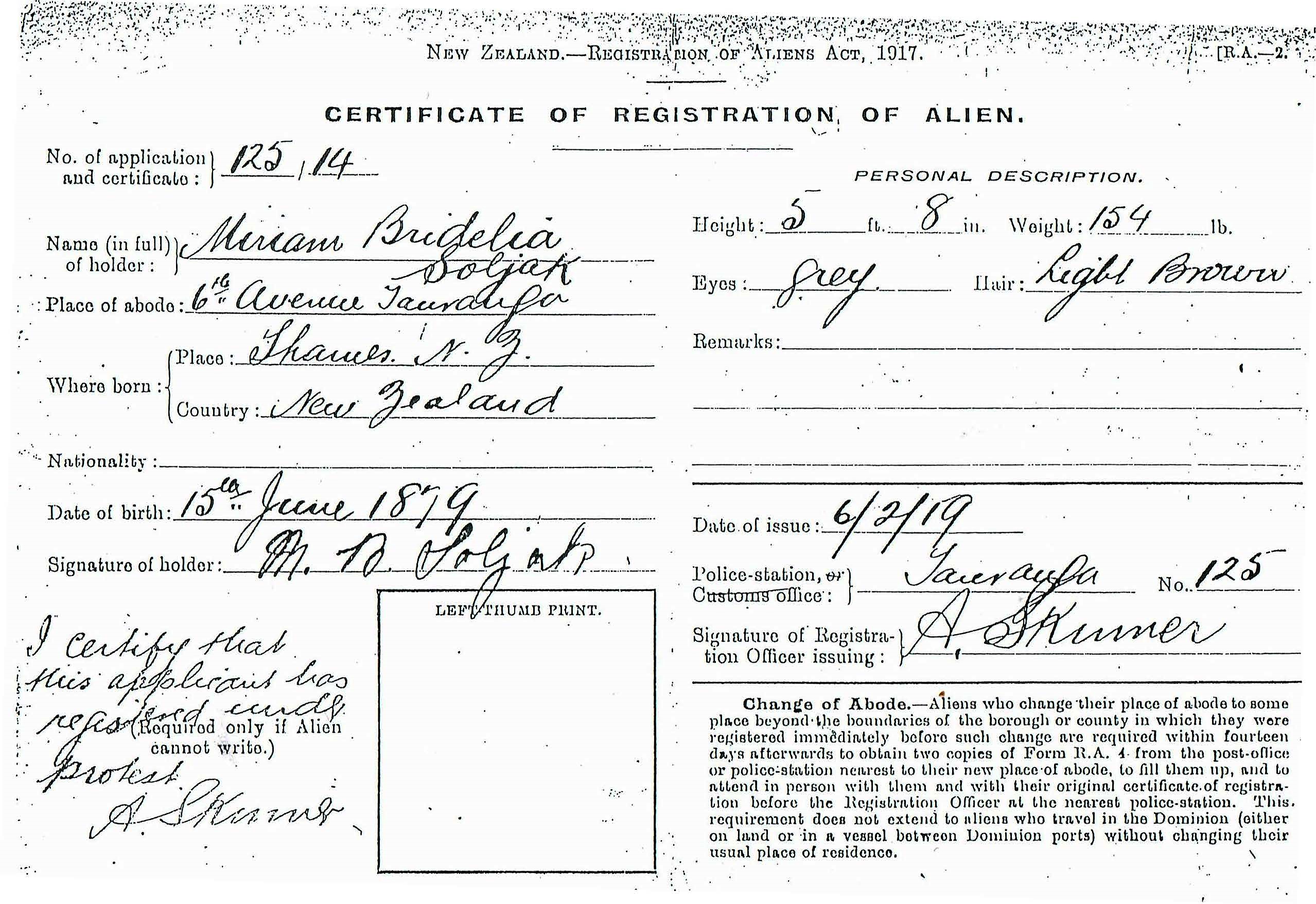

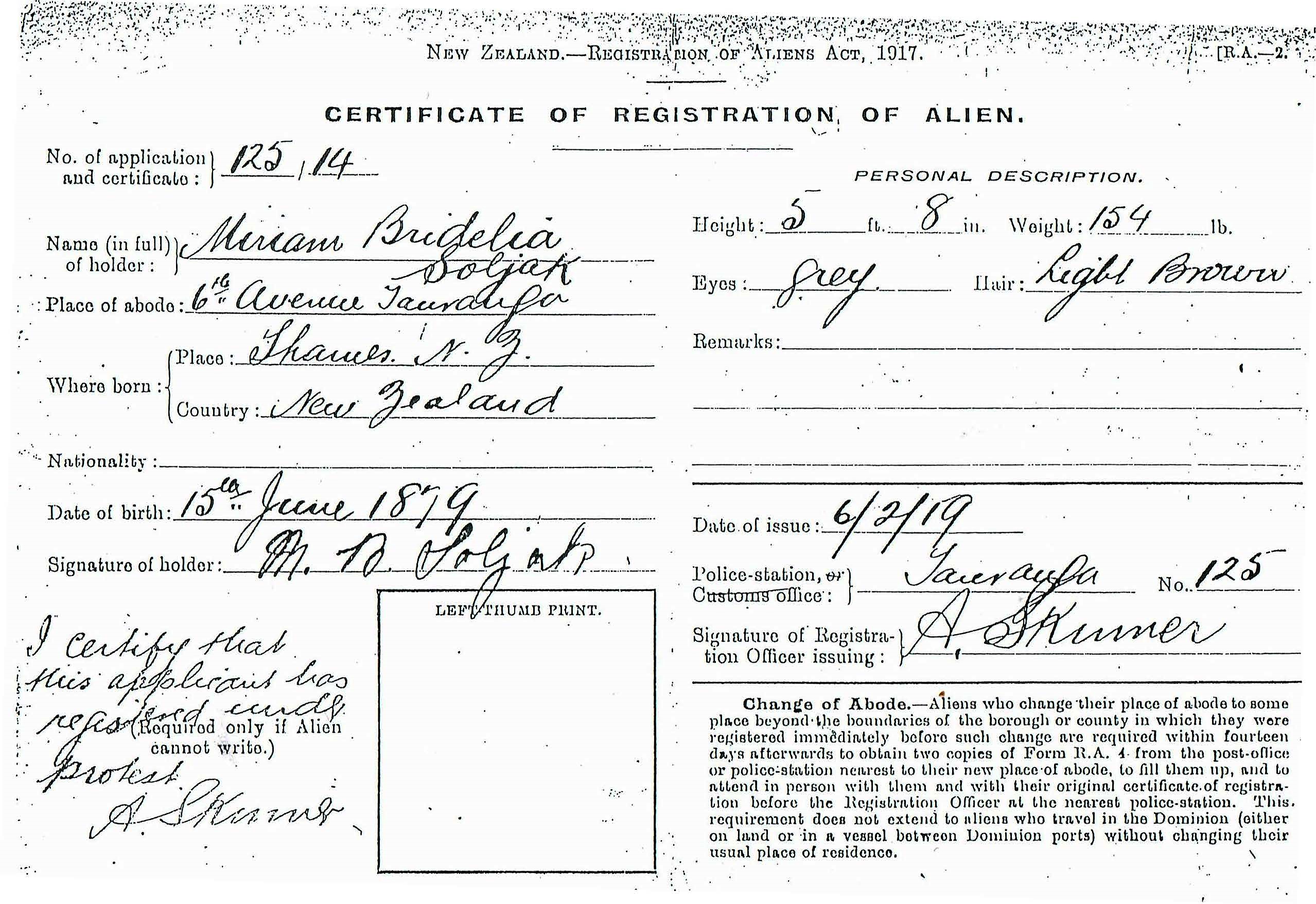

by marrying a foreigner. Given the option of prison or registration, Soljak registered as an alien "under protest". The action also revoked her right to vote.

Nationality issues and beginning of activism

New Zealand's first nationality law, the Aliens Act of 1866, specified that foreign women who married New Zealanders automatically acquired the nationality of the husband. It applied only to the wives of

New Zealand's first nationality law, the Aliens Act of 1866, specified that foreign women who married New Zealanders automatically acquired the nationality of the husband. It applied only to the wives of British subjects

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

. Because of the way British nationality laws were drafted, persons became subjects or were naturalised as British based upon local definitions for each jurisdiction. There was not an overriding imperial definition for who was a British subject. This meant that someone could be a British subject in one part of the empire, but not considered British in another part of the dominions of Britain. In 1914, this was rectified when the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act provided that the nationality of a British subject would be the same for each place within the realm. New Zealand introduced a measure to adopt the common code of British nationality in 1914, but passage was postponed by the outbreak of the war.

War measures such as the 1916 Amendment to the War Regulations Act and the Revocation of Naturalisation Act and Registration of Aliens Act of 1917 addressed denaturalisation procedures for women. Under the 1916 amendment, wives of enemy aliens were automatically denaturalised as enemy aliens, even if they had been born British. Provisions in the 1917 Revocation of Naturalisation Act stated that revocation of an enemy alien's nationality did not impact his wife and minor children. The Registration Act merely required an alien to list the names and ages of his wife and children. However, an amendment to the Registration of Aliens Act in 1920 clarified that married women in New Zealand who lost their nationality because of marriage were required to register as aliens. Despite the contradictory provisions in the law, women like Soljak were deprived of their nationality during the war. The experience turned her life towards activism, bringing her to national prominence.

Political activism (1920–1946)

In 1920, the family moved to Auckland and Soljak joined the Auckland Women's Political League, which five years later became the Auckland women's branch of theNew Zealand Labour Party

The New Zealand Labour Party ( mi, Rōpū Reipa o Aotearoa), or simply Labour (), is a centre-left political party in New Zealand. The party's platform programme describes its founding principle as democratic socialism, while observers descr ...

. Soljak led a public fight, alongside Elizabeth McCombs

Elizabeth Reid McCombs (née Henderson, 19 November 1873 – 7 June 1935) was a New Zealand politician of the Labour Party who in 1933 became the first woman elected to the New Zealand Parliament. New Zealand women gained the right to vote in ...

, against the nationality laws, speaking to Parliament and publishing articles in the local papers on the unfairness of the legislation. With the break-up of the Austrian Empire, Peter chose to align his nationality with the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes

Kingdom commonly refers to:

* A monarchy ruled by a king or queen

* Kingdom (biology), a category in biological taxonomy

Kingdom may also refer to:

Arts and media Television

* ''Kingdom'' (British TV series), a 2007 British television drama s ...

, later Yugoslavia, in 1922. In 1923, New Zealand adopted the British nationality scheme, which clearly specified that New Zealand women who married foreign men automatically lost their nationality upon marriage. Working with allies like Emily Gibson and Peter Fraser

Peter Fraser (; 28 August 1884 – 12 December 1950) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 24th prime minister of New Zealand from 27 March 1940 until 13 December 1949. Considered a major figure in the history of the New Zealand Lab ...

, Soljak pressed for legislation for women to have independent nationality. Fraser introduced a bill in 1927, but it was unsuccessful. In 1928, Peter Soljak naturalised, and through his action Soljak regained her British nationality under an amendment passed in 1935, but only while in New Zealand. When travelling abroad, she had to use a passport which was marked "New Zealand born, wife of an alien, now naturalised" and regularly register with the police.

From 1926, Soljak worked on women's issues. She fought for women to receive

From 1926, Soljak worked on women's issues. She fought for women to receive unemployment benefits

Unemployment benefits, also called unemployment insurance, unemployment payment, unemployment compensation, or simply unemployment, are payments made by authorized bodies to unemployment, unemployed people. In the United States, benefits are fun ...

, as politicians ignored their homelessness

Homelessness or houselessness – also known as a state of being unhoused or unsheltered – is the condition of lacking stable, safe, and adequate housing. People can be categorized as homeless if they are:

* living on the streets, also kn ...

and their need to work. In 1931, she worked on the Auckland Unemployed Women's Emergency Committee, but resigned when she realised there were no funds to help women and that their actions would only be to compile a registry of unemployed women. Because of the perception that many Māori women participated in prostitution

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in Sex work, sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, n ...

, Soljak pressed for training to combat their economic hardships and the social ostracism they experienced in the workplace. She stressed that Māori women and girls had civil rights and should be able to choose their own employment and be free of exploitation. She pointed out that Māori women often had to take whatever work they could find. This was borne out in an inquiry undertaken by the Labour Department at the insistence of the Akarana Maori Association, which found few instances of immorality among Maori girls and women, but noted they had difficulty earning enough to provide for themselves and their families. She suggested that hostels be established to train Māori women in child care, domestic service, and nursing.

Soljak was involved in the pacifist movement, as well as advocating for sex education

Sex education, also known as sexual education, sexuality education or sex ed, is the instruction of issues relating to human sexuality, including emotional relations and responsibilities, human sexual anatomy, Human sexual activity, sexual acti ...

and programmes to address maternal and child mortality, child welfare, and payments to mothers to recognise their contributions to the nation through raising children. She began working as a freelance journalist

''Freelance'' (sometimes spelled ''free-lance'' or ''free lance''), ''freelancer'', or ''freelance worker'', are terms commonly used for a person who is self-employed and not necessarily committed to a particular employer long-term. Freelance w ...

and was a sought-after public speaker, though her style was hard-hitting and confrontational. In 1928, Soljak was elected president of the Auckland women's branch of the Labour Party and re-elected to the post in 1929. The Soljaks separated in 1929, primarily because Peter did not agree with her radical politics and the people with whom she was associating. The following year, she sought a legal separation, but Peter refused to agree, denying Soljak alimony

Alimony, also called aliment (Scotland), maintenance (England, Ireland, Northern Ireland, Wales, Canada, New Zealand), spousal support (U.S., Canada) and spouse maintenance (Australia), is a legal obligation on a person to provide financial suppo ...

or child maintenance

Child support (or child maintenance) is an ongoing, periodic payment made by a parent for the financial benefit of a child (or parent, caregiver, guardian) following the end of a marriage or other similar relationship. Child maintenance is paid d ...

. Working with the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom

The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) is a non-profit non-governmental organization working "to bring together women of different political views and philosophical and religious backgrounds determined to study and make kno ...

between 1930 and 1931, she led an initiative to assist women in Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

. She condemned the suppression of Samoa's pro-independence Mau movement

The Mau was a non-violent movement for Samoan independence from colonial rule during the first half of the 20th century. ''Mau'' means ‘resolute’ or ‘resolved’ in the sense of ‘opinion’, ‘unwavering’, ‘to be decided’, or ...

in 1930, and was at odds with the Labour Party hierarchy over the issue. After she wrote an article in May, which was published in the ''Samoa Guardian'' protesting searches of the homes of independence leaders, she was ousted from the women's branch of the Labour Party. She then aligned with the Communist Party of New Zealand

The Communist Party of New Zealand (CPNZ) was a communist party in New Zealand which existed from 1921 to 1994. Although spurred to life by events in Soviet Russia in the aftermath of World War I, the party had roots in pre-existing revolutiona ...

and joined other radical organisations.

After being counselled by a priest that family size could be controlled by abstinence, Soljak left the Catholic church and began campaigning for women to be able to gain access to contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

and family planning

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marita ...

. Using the pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

"Zealandia", she wrote a series of articles for ''The New Zealand Herald

''The New Zealand Herald'' is a daily newspaper published in Auckland, New Zealand, owned by New Zealand Media and Entertainment, and considered a newspaper of record for New Zealand. It has the largest newspaper circulation of all newspapers ...

'' on the topic and attended a Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

conference in 1934, advocating for birth control. After the conference, she helped found the Sex Hygiene and Birth Regulation Society, renamed the New Zealand Family Planning Association in 1940. In 1935, Soljak led a deputation of members of the Women Workers' Movement to the Prime Minister's office to demand changes to the Women's Unemployment Committees. In the manifesto she presented were demands to disband the committees and terminate the current leadership replacing them with labour bureaux for women, which would be run by women; for government employment placement services for women; for payments to elders, the infirm, and widows; and revised policies concerning separated wives of men who were obtaining relief subsidies.

Under the sponsorship of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, Soljak attended a Commonwealth women's conference in London (1936–37), where presentations covered such topics as the lack of equal rights for women, peace and social initiatives, trafficking, and women's nationality and immigration rights. She presented a talk to the conference on women's nationality issues in New Zealand. Soljak was finally awarded family maintenance in 1936, but during her trip abroad, Peter attempted to terminate the payments. In 1938, she filed for divorce and was granted a decree nisi

A decree nisi or rule nisi () is a court order that will come into force at a future date unless a particular condition is met. Unless the condition is met, the ruling becomes a decree absolute (rule absolute), and is binding. Typically, the condi ...

, and the divorce was finalised in 1939. Soljak found that she was still classed as a foreign national

A foreign national is any person (including an organization) who is not a national of a specific country. ("The term 'person' means an individual or an organization.") For example, in the United States and in its territories, a foreign national ...

, despite her New Zealand birth and the termination of her marriage, as the law had no provisions for a woman to recover her nationality lost upon marriage. When the Social Security Act

The Social Security Act of 1935 is a law enacted by the 74th United States Congress and signed into law by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The law created the Social Security program as well as insurance against unemployment. The law was pa ...

was passed in 1938, she wrote an article in ''Women Today'' criticising the fact that though the act entitled single women workers to an unemployment benefit, it paid married women's benefits to their husbands.

Soljak joined the New Zealand Rationalist Association in 1940 and in 1941 was elected to serve on the executive committee. The organisation protested the government's treatment of

Soljak joined the New Zealand Rationalist Association in 1940 and in 1941 was elected to serve on the executive committee. The organisation protested the government's treatment of conscientious objector

A conscientious objector (often shortened to conchie) is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion. The term has also been extended to object ...

s. That year she continued her campaign against the nationality law, speaking on behalf of the United Women's Movement delegation to the Minister of Internal Affairs

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

. She pointed out that women should have their own nationality and that the current law also impacted the nationality of their children. Soljak continued to campaign throughout the war on behalf of the United Women's Movement, serving as its treasurer in 1944, and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. She pressed for adequate housing for families, as most of the available units had been given to soldiers; for not allowing children's protection to lose focus because of attention to the war effort; and for peace initiatives. At the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, she retired from public life to look after her son Paul, who had been wounded in the war. They lived in Point Chevalier

Point Chevalier (; commonly known as Point Chev and an original colonial name of Point Bunbury after Thomas Bunbury) is a residential suburb and peninsula in the city of Auckland in the north of New Zealand. It is located five kilometres to th ...

. In 1946, Soljak's nationality was restored, when the New Zealand nationality law was finally revised to grant women individual nationality. In the letter from the Internal Affairs Minister, signed by under-secretary Joe Heenan

Sir Joseph William Allan Heenan (17 January 1888 – 11 October 1951) was a New Zealand law draftsman, senior public servant, administrator and writer. He was born in Greymouth, New Zealand, on 17 January 1888.

Heenan was awarded the King Ge ...

, which responded to her request for restoration of her nationality, he stated, "you are deemed never to have lost your British nationality". Eventually, she rejoined the Labour Party and was given a gold badge of service for her work over many years.

Death and legacy

Soljak died in Auckland on 28 March 1971. She is remembered for her advocacy on behalf of working women and the Māori people, as well as her decades-long efforts to address gender discrimination in nationality laws. The Soljak family papers are housed in the Dalmatian Archive of the Auckland Council Libraries. Her son Philip became an author and her daughterConnie Purdue

Constance Miriam Purdue (née Soljak, 23 May 1912 – 16 March 2000) was a New Zealand trade unionist. Formerly a communist and a New Zealand Labour Party, Labour Party member, she later became a conservative Catholic and an anti-abortion acti ...

went on to become a leading name in the New Zealand anti-abortion

Anti-abortion movements, also self-styled as pro-life or abolitionist movements, are involved in the abortion debate advocating against the practice of abortion and its legality. Many anti-abortion movements began as countermovements in respons ...

movement. In 2020, Soljak was the subject of a series of mixed-media acrylic paintings, featured at the Waiheke Community Art Gallery as "Signed under Protest" and created by her granddaughter, Katy Soljak.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Soljak, Miriam 1879 births 1971 deaths 19th-century New Zealand women 20th-century New Zealand women politicians 20th-century New Zealand politicians New Zealand communists New Zealand pacifists New Zealand people of Irish descent New Zealand people of Scottish descent New Zealand socialist feminists New Zealand women's rights activists Pacifist feminists People from Hastings, New Zealand People from Thames, New Zealand Women's International League for Peace and Freedom people