Minnie Fisher Cunningham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Minnie Fisher Cunningham (March 19, 1882 – December 9, 1964) was an American suffrage politician, who was the first executive secretary of the

Cunningham broadened her network base by reaching out to labor union organizers such as Eva Goldsmith, president of Texas District Council of United Garment Workers Union. In 1915, Cunningham contributed five women's suffrage articles to the Texas State Federation of Labor (TSFL) publication ''Labor Dispatch''. She devoted considerable time and effort to promote the TWSA petition to the Texas State Legislature for an amendment to the state constitution to enable women to vote. Towards the amendment push, Californian Helen Todd was brought in to speak at events, as was

Cunningham broadened her network base by reaching out to labor union organizers such as Eva Goldsmith, president of Texas District Council of United Garment Workers Union. In 1915, Cunningham contributed five women's suffrage articles to the Texas State Federation of Labor (TSFL) publication ''Labor Dispatch''. She devoted considerable time and effort to promote the TWSA petition to the Texas State Legislature for an amendment to the state constitution to enable women to vote. Towards the amendment push, Californian Helen Todd was brought in to speak at events, as was

She was a founding member of the Woman's National Democratic Club.McArthur, Judith. ''Minnie Fisher Cunningham : A Suffragist's Life in Politics'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, page 124.

She was a founding member of the Woman's National Democratic Club.McArthur, Judith. ''Minnie Fisher Cunningham : A Suffragist's Life in Politics'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2005, page 124.

Cunningham ran in the 1928 election to represent the state of Texas in the United States Senate, the first woman in Texas to do so. Her opponent was the incumbent Earle B. Mayfield. Her goal in choosing to run was to elevate the status of women in the electorate. She ran on issues, forsaking the combative style of politics that historically dominated elections. In doing so, she disregarded advice from many, including her long-time ally Alexander Caswell Ellis. Cunningham lost in the state's primary.

Cunningham ran in the 1928 election to represent the state of Texas in the United States Senate, the first woman in Texas to do so. Her opponent was the incumbent Earle B. Mayfield. Her goal in choosing to run was to elevate the status of women in the electorate. She ran on issues, forsaking the combative style of politics that historically dominated elections. In doing so, she disregarded advice from many, including her long-time ally Alexander Caswell Ellis. Cunningham lost in the state's primary.

League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV or the League) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization in the United States. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for vot ...

, and worked for the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution giving women the vote. A political worker with liberal views, she became one of the founding members of the Woman's National Democratic Club. In her position overseeing the club's finances, she assisted in the organization's purchase of its Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

headquarters, which is still in use.

Cunningham was descended from wealthy plantation slaveholders who had moved to Texas from Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

. By the time she was born in 1882, the family fortunes had been dissipated by the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, forcing her mother to sell vegetables to make ends meet. She holds the distinction of being the first female student of the University of Texas Medical Branch

The University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) is a public academic health science center in Galveston, Texas. It is part of the University of Texas System. UTMB includes the oldest medical school in Texas, and has about 11,000 employees. In Febr ...

in Galveston

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

to earn a Graduate of Pharmacy degree.

As a member of the National American Women's Suffrage Association, Cunningham helped persuade Senator Andrieus Aristieus Jones of New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

, chair of the Senate Woman Suffrage Committee, to introduce the amendment for a vote. Cunningham was part of a team who met with President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

in the Oval Office, successfully coaxing the President into releasing a statement expressing a leaning towards suffrage. When Texas Governor James E. Ferguson actively opposed the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Cunningham formed a coalition that helped impeach the governor.

She was active for decades in both national and Texas state politics. In 1928, Cunningham became the first woman from Texas to run for the United States Senate. She supported the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

policies and programs of Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, and sought to uplift the status of the disenfranchised in the country. Cunningham saw the connection between poverty and nutrition, and worked for government legislation to require nutrient enrichment of flour and bread. Cunningham's 1944 Texas gubernatorial candidacy against incumbent Coke Stevenson

Coke Robert Stevenson (March 20, 1888 – June 28, 1975) was an American politician who served as the 35th governor of Texas from 1941 to 1947. He was the first Texan politician to hold its three highest offices (Speaker of the Texas Hou ...

garnered her second place in a field of nine candidates. To meet the expenses of running a county campaign office for John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

's presidential race, she sold used clothing.

Early life and background

Minnie Fisher was born the seventh of eight children to Horatio White Fisher and his wife Sallie Comer Abercrombie Fisher on March 19, 1882, inNew Waverly, Texas

New Waverly is a city in Walker County, Texas, United States. The population was 914 at the 2020 census.

Geography

New Waverly is located at (30.539226, –95.479862).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area o ...

, on land that would become known as Fisher Farms. Sallie Comer Abercrombie was the only child of John Comer Abercrombie and Jane Minerva Sims Abercrombie, who had moved to Texas in the 1850s from Macon County, Alabama

Macon County is a county located in the east central part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the population was 19,532. Its county seat is Tuskegee. Its name is in honor of Nathaniel Macon, a member of the United States Senat ...

to become one of the largest land holders in Walker County. Minnie's paternal grandfather William Phillips Fisher had moved to Walker County from Lowndes County, Alabama

Lowndes County is in the central part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the county's population was 10,311. Its county seat is Hayneville. The county is named in honor of William Lowndes, a member of the United States Con ...

and was the owner of 92 slaves. Minnie's father Horatio had been the owner of 72 slaves and was elected to Texas State Legislature

The Texas Legislature is the state legislature of the US state of Texas. It is a bicameral body composed of a 31-member Senate and a 150-member House of Representatives. The state legislature meets at the Capitol in Austin. It is a powerful arm ...

in 1857. When Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

broke out, Horatio raised a cavalry company for the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

. On furlough during the war, Horatio married Sallie. Of their eight children, seven survived to adulthood.

Waverly had been settled in Walker County in 1835 by an Alabama plantation owner named James W. Winters. When San Jacinto County was formed in 1870, Waverly became a part of the new county. The Houston and Great Northern Railroad was denied right-of-way through Waverly, and instead laid tracks ten miles to the west in Walker County where it placed Waverly Station. Many from the original Waverly were attracted to the locale, and it became New Waverly. The Waverly in San Jacinto became known as Old Waverly. The war and reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

stripped Horatio and Sallie of their wealth, and they were forced to move in with Sallie's parents. It was at the Abercrombie plantation where Minnie and her siblings grew up. By that point in time, slave labor had been replaced by sharecroppers. The children were home schooled by Sallie until 1894. The family business became selling produce to railroad workers, eventually expanding to marketing the produce in Houston. Sallie used the proceeds of the produce business to finance formal schooling for her children.

Minnie received her spiritual grounding from the Methodists and was instrumental in helping found a Methodist church in New Waverly. After the Galveston Hurricane of 1900

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

, Minnie and her mother Sallie held a fund raising effort in New Waverly. Her political interests stemmed from her father. Although she passed the state teacher certification examination, Minnie chose medicine as her field of study. She enrolled at the University of Texas Medical Branch

The University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) is a public academic health science center in Galveston, Texas. It is part of the University of Texas System. UTMB includes the oldest medical school in Texas, and has about 11,000 employees. In Febr ...

in Galveston

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

School of Pharmacy. In 1901, Minnie became her alma mater's sole female to earn a Graduate of Pharmacy Degree. She found employment in Huntsville

Huntsville is a city in Madison County, Limestone County, and Morgan County, Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Madison County. Located in the Appalachian region of northern Alabama, Huntsville is the most populous city in th ...

, but earned less than half the wages of her less-educated male co-workers. Minnie would later cite this experience as her motivation in elevating the status of women.

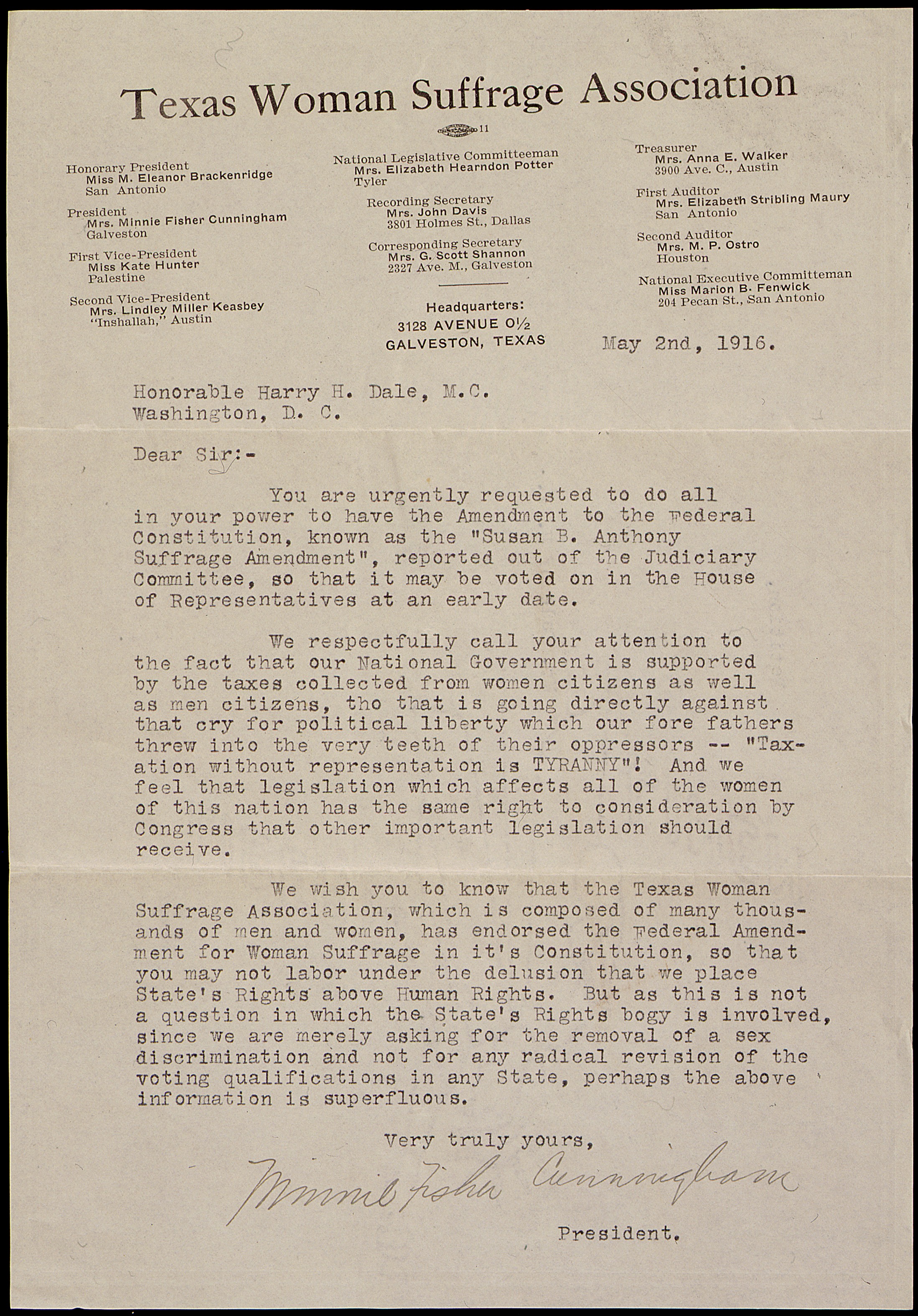

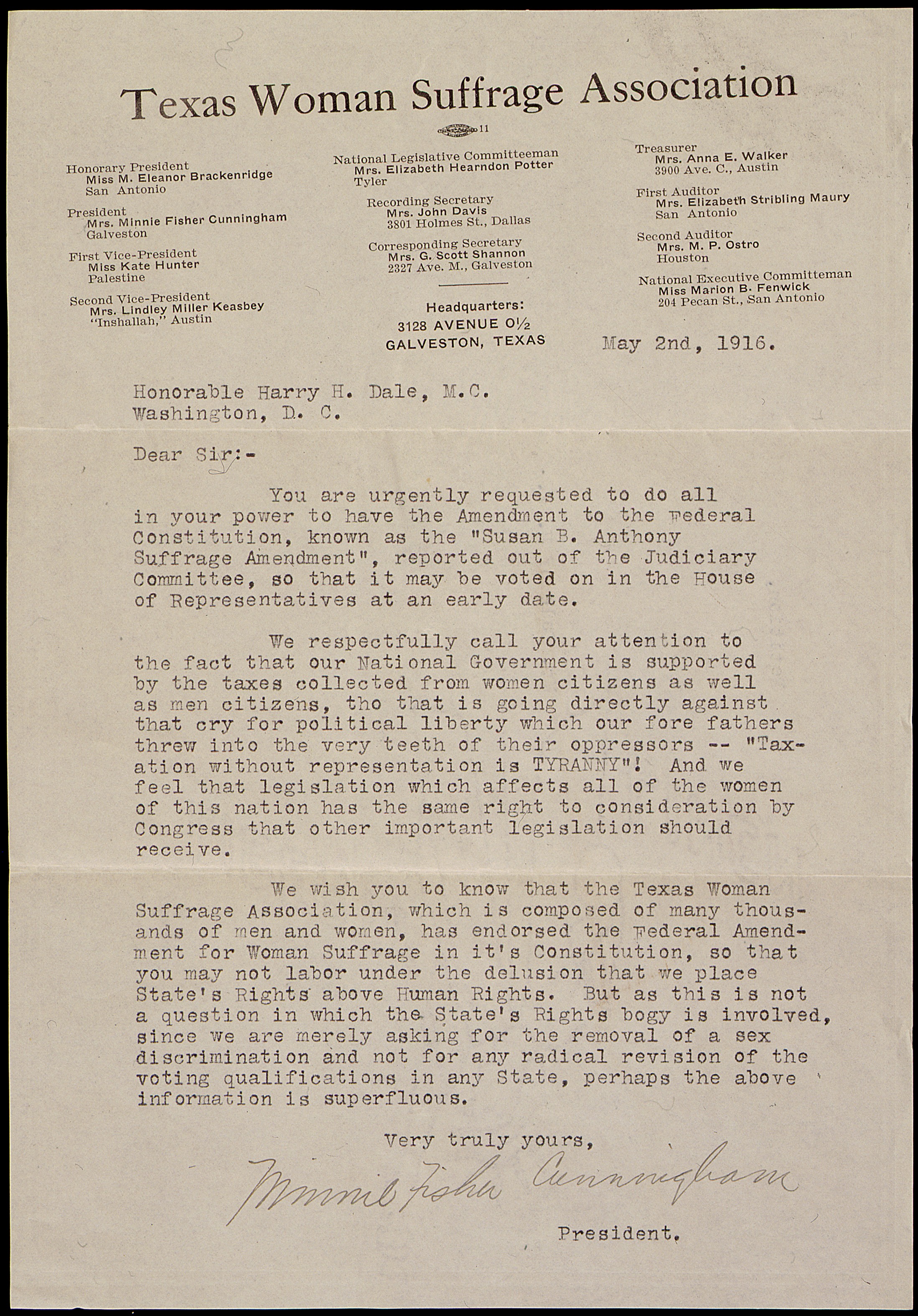

First involvement with suffrage issues

After her 1902 marriage to B. J. Cunningham, she became involved in volunteer organizations. One of these in 1912 was the Wednesday Club, which in part focused on women's suffrage and children's rights. She further became interested in women's issues as a member of theWomen's Health Protective Association

Women's Health Protective Association (sometimes, Woman's Health Protective Association; original parent body, Ladies' Health Protective Association) was a US women's organization focused on improving a city's public health and protecting the imme ...

(WHPA) and the Galveston Equal Suffrage Association (GESA). It was in these organizations where Cunningham developed her skill for public oratory, accepting speaking engagements at public events and before groups of legislators Cunningham became involved with the Texas Woman Suffrage Association (TWSA). In 1913, the organization became affiliated with the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA). In 1914, Cunningham was elected president of GESA. She began networking with other prominent suffrage persons such as TWSA president Mary Eleanor Brackenridge

Mary Eleanor Brackenridge (March 7, 1837 – February 14, 1924) was one of three women on the first board of regents at Texas Woman's University, the first women in the state of Texas to sit on a governing board of any university. She was active in ...

of San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= U.S. state, State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, s ...

, British politician Ethel Snowden

Ethel Snowden, Viscountess Snowden (born Ethel Annakin; 8 September 1881 – 22 February 1951), was a British socialist, human rights activist, and feminist politician. From a middle-class background, she became a Christian Socialist thro ...

and TWSA co-leader Annette Finnigan

Annette Finnigan (1873 – July 17, 1940) was an American suffragette, philanthropist, and patron of the arts.

Early life

Annette Finnigan was born in 1873 to Katherine McRedmond and John Finnigan in West Columbia, Texas. John was a successful ...

of Houston,Texas Through Women's Eyes (2010) p.27 who became Cunningham's mentor. Under Cunningham's guidance, GESA held a public department store event on May 2, 1914, that included speeches by Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

attorney and lobbyist Annette Funk. Cunningham organized GESA events during the Galveston Cotton Carnival, featuring speaker Perle Penfield, a Galveston university medical student hired by Finnigan as a summer intern.

Cunningham broadened her network base by reaching out to labor union organizers such as Eva Goldsmith, president of Texas District Council of United Garment Workers Union. In 1915, Cunningham contributed five women's suffrage articles to the Texas State Federation of Labor (TSFL) publication ''Labor Dispatch''. She devoted considerable time and effort to promote the TWSA petition to the Texas State Legislature for an amendment to the state constitution to enable women to vote. Towards the amendment push, Californian Helen Todd was brought in to speak at events, as was

Cunningham broadened her network base by reaching out to labor union organizers such as Eva Goldsmith, president of Texas District Council of United Garment Workers Union. In 1915, Cunningham contributed five women's suffrage articles to the Texas State Federation of Labor (TSFL) publication ''Labor Dispatch''. She devoted considerable time and effort to promote the TWSA petition to the Texas State Legislature for an amendment to the state constitution to enable women to vote. Towards the amendment push, Californian Helen Todd was brought in to speak at events, as was Harriot Stanton Blatch

Harriot Eaton Blatch ( Stanton; January 20, 1856–November 20, 1940) was an American writer and suffragist. She was the daughter of pioneering women's rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Biography

Harriot Eaton Stanton was born, the sixt ...

, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

. Although the amendment was defeated, Cunningham continued to work tirelessly on suffrage, hosting physician, minister and suffrage supporter Anna Howard Shaw

Anna Howard Shaw (February 14, 1847 – July 2, 1919) was a leader of the women's suffrage movement in the United States. She was also a physician and one of the first ordained female Methodist ministers in the United States.

Early life

Shaw ...

.

In 1915, TWSA elected Cunningham as its president. Over the long haul, Cunningham would serve as president until 1919. In 1916, TWSA changed its name to Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA). Finances of TESA and how to make the organization self-sustaining were at the forefront of Cunningham's agenda. She often borrowed money to fund TESA. She ran TESA from her own home, using it as the organization's headquarters. International Woman Suffrage Alliance

The International Alliance of Women (IAW; french: Alliance Internationale des Femmes, AIF) is an international non-governmental organization that works to promote women's rights and gender equality. It was historically the main international org ...

president Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (; January 9, 1859 Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt ...

sent freelance organizer Elizabeth Freeman

Elizabeth Freeman ( 1744 December 28, 1829), also known as Bet, Mum Bett, or MumBet, was the first enslaved African American to file and win a freedom suit in Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruling, in Freeman's favor, ...

and NAWSA freelance organizer Lavinia Engle

Lavinia Margaret Engle (May 23, 1892 – May 29, 1979) was an American suffragette and politician. She was a member of the Maryland House of Delegates and Montgomery County, Maryland, Montgomery County Board of Commissioners, leader of the Nationa ...

from Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

to rally support.

James E. Ferguson

Texas Governor James E. Ferguson and former United States Senator from TexasJoseph Weldon Bailey

Joseph Weldon Bailey, Sr. (October 6, 1862April 13, 1929), was a United States senator, United States Representative, lawyer, and Bourbon Democrat who was famous for his speeches extolling conservative causes, such as opposition to woman suffrag ...

stood in staunch opposition to a Constitutional amendment for women's suffrage in 1916, lumping it together with prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

as a states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

issue. They spoke against it at the state Democratic convention in San Antonio, and as part of the minority report presented at the Democratic National Convention in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

. As part of the NAWSA contingent at the convention, Cunningham led a protest against Ferguson. When Cunningham returned to Texas, she and Lavinia Engle toured south Texas urging people to vote against Ferguson in the primary.

Cunningham moved the TESA headquarters to Austin in 1917 when the Texas State Legislature

The Texas Legislature is the state legislature of the US state of Texas. It is a bicameral body composed of a 31-member Senate and a 150-member House of Representatives. The state legislature meets at the Capitol in Austin. It is a powerful arm ...

began considering a primary suffrage bill that ultimately failed to pass. At the same time, there was a growing possibility of impeachment of Governor Ferguson over numerous practices that included appropriations and appointments at the University of Texas. Cunningham made an alliance with university professor Mary Gearing and Austin suffrage people to form the Women's Campaign for Good Government (WCGG). The organization was joined by the Ex-Students Association and William Clifford Hogg, son of former Governor Jim Hogg. The coalition deluged legislators with letters and telegrams. The legislature called a special investigative session, and the WCGG took to the streets and handed out a flyer listing what it believed were impeachable acts of Ferguson. Ferguson was impeached on ten counts, and forbidden to hold office in Texas. He resigned from office on August 25, 1917.

After the American entry into World War I

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry

...

, Cunningham involved TESA in patriotic work, such as the campaign for Liberty bond

A liberty bond (or liberty loan) was a war bond that was sold in the United States to support the Allied cause in World War I. Subscribing to the bonds became a symbol of patriotic duty in the United States and introduced the idea of financia ...

s. The organization became involved in an anti-vice campaign focused on military bases. The Woman's Anti-Vice Committee was aimed at providing wholesome alternatives to bars and a deterrent to prostitution, as was the Texas Social Hygiene Association. In 1918, Cunningham received an appointment to the Texas Military Welfare Commission.

In spite of the terms of his impeachment banning him from elected office, Ferguson announced his candidacy for governor in 1918. Acting governor William P. Hobby

William Pettus Hobby (March 26, 1878 – June 7, 1964) was known as the publisher/owner of the '' Beaumont Enterprise'' when he entered politics and the Democratic Party. Elected in 1914 as Lieutenant Governor of Texas, in 1917 he succeeded t ...

was likely to be voted out of office in the wake of Ferguson's illegitimate candidacy. Cunningham worked behind the scenes with state representative Charles Metcalfe to cut a deal for primary suffrage, which would allow women in Texas to vote in the primary elections but not in the general elections. If he would get a primary suffrage bill passed, and signed by Governor Hobby, she would deliver him the women's votes. Metcalfe got the bill passed and Hobby signed the bill on May 26. The women conducted a grass roots campaign named Women's Hobby Clubs to deliver promised votes. The group persuaded university professor Annie Webb Blanton to run for State Superintendent of Public Instruction. The women's vote helped propel Blanton to a primary victory. Blanton went on to win in the November general election and became the first woman in Texas elected to statewide office.

Passage of the 19th amendment

Cunningham made arrangements with United States Senator from TexasMorris Sheppard

John Morris Sheppard (May 28, 1875April 9, 1941) was a Democratic United States Congressman and United States Senator from Texas. He authored the Eighteenth Amendment (Prohibition) and introduced it in the Senate, and is referred to as "the fa ...

in 1917 for a conference in his Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

office for women to state their perspectives on the proposed suffrage amendment to the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. She and NAWSA lobbyist Maud Wood Park

Maud Wood Park (January 25, 1871 – May 8, 1955) was an American suffragist and women's rights activist.

Career overview

She was born in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1887 she graduated from St. Agnes School in Albany, New York, after which she ta ...

, who would become the first president of the League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV or the League) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization in the United States. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for vot ...

, initiated a campaign for constituents to flood the offices of their representatives with telegrams in favor of passage.McArthur, Smith (2005) p.70 The United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

passed the first version of the Nineteenth Amendment on January 10, 1918, but it failed in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

.

Alexander Caswell Ellis, a professor at the University of Texas who had been fired by Governor Ferguson, and reinstated after Ferguson's resignation of office, teamed up with Cunningham to pressure Texas newspapers to run editorials in favor of the amendment. Senator Charles Allen Culberson, who had also been the 21st Governor of Texas, was anti-suffrage. Caswell and Cunningham clipped pro-suffrage editorials from Texas newspapers and forwarded the clippings to Culberson's office daily.

NAWSA pressed Cunningham into service as a lobbyist, to persuade Senator Andrieus Aristieus Jones of New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

, chair of the Senate Woman Suffrage Committee, to introduce the amendment for a vote. Jones complied. They also recruited Cunningham as part of a team to meet with President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

in the Oval Office, successfully coaxing the President into releasing a statement expressing a leaning towards suffrage.McArthur, Smith (2005) pp.71,72

In January 1919, the Texas state legislature passed a state amendment authorizing full suffrage for women. It was subject to referendum by state voters, and subsequently failed the referendum. A joint resolution on the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed by the United States House of Representatives on May 21, 1919, passing in the United States Senate on June 4, 1919. Cunningham proceeded immediately to campaign for ratification by the Texas legislature. Texas became the first southern state to ratify the amendment on June 28, 1919. Cunningham teamed with Jessie Jack Hooper

Jessie Annette Jack Hooper (November 9, 1865 – May 7, 1935) was an American peace activist and suffragist, who was the first president of the Wisconsin League of Women Voters. She became involved in women's suffrage as an empowerment for wo ...

, first vice president of Wisconsin Women's Suffrage Association, on a national tour for ratification. The thirty-six states out of the then existing forty-eight needed for the three-fourths ratification was reached on August 26, 1920.

League of Women Voters

With the amendment now a reality, NAWSA became theLeague of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV or the League) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization in the United States. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for vot ...

(LWV). Cunningham was chosen as a delegate at large to the 1920 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco. TESA became Texas League of Women Voters (TLWV) in 1919.

R. Ewing Thomason

Robert Ewing Thomason known as R. Ewing Thomason (May 30, 1879 – November 8, 1973) was a Texas politician, a member and Speaker of the Texas House of Representatives, the mayor of El Paso, a Democratic member of the United States House of Repr ...

was a member of the Texas House of Representatives and had been on the committee that investigated Governor Ferguson. In 1920, Thomason ran for governor against Joseph Weldon Bailey

Joseph Weldon Bailey, Sr. (October 6, 1862April 13, 1929), was a United States senator, United States Representative, lawyer, and Bourbon Democrat who was famous for his speeches extolling conservative causes, such as opposition to woman suffrag ...

and lost. Cunningham had organized the Woman's Committee for Thomason and considered it a victory that Thomason had forced Bailey into a run-off against the eventual winner Pat Neff

Pat Morris Neff (November 26, 1871 – January 20, 1952) was an American politician, educator and administrator, and the 28th Governor of Texas from 1921 to 1925, ninth President of Baylor University from 1932 to 1947, and twenty-fifth presid ...

.

Maud Wood Park was elected in 1920 as president of the Women's Joint Congressional Committee (WJCC) lobby organization. Park brought Cunningham back into service to work with Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

Congressman Horace Mann Towner

Horace Mann Towner (October 23, 1855 – November 23, 1937) was an American politician who served as a member of the United States House of Representatives from Iowa's 8th congressional district and appointed the governor of Puerto Rico. In an ...

and Texas Senator Morris Sheppard

John Morris Sheppard (May 28, 1875April 9, 1941) was a Democratic United States Congressman and United States Senator from Texas. He authored the Eighteenth Amendment (Prohibition) and introduced it in the Senate, and is referred to as "the fa ...

to pass the 1921 Sheppard-Towner Maternity and Infancy Act. The act was designed to lower infant mortality rate, and Cunningham, as executive secretary of the LWV, campaigned to get the individual states to accept the Act. Cunningham became Park's right hand and pinch hitter. The duo worked together with Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

Congressman John L. Cable for passage of the 1922 Married Women's Independent Citizenship Act, and for its 1930 and 1931 amending. Prior to this Act, women's citizenship, or lack thereof, was totally dependent upon their husband's status. The bill was designed for a woman's citizenship to be based solely on her own status.

Cunningham and Lavinia Engle worked together to combine the LWV's 1922 Baltimore convention with the Pan-American Conference of Women

Pan-American Conference of Women occurred in Baltimore, Maryland, US in 1922. It was held in connection with the third annual convention of the League of Women Voters, National League of Women Voters in Baltimore on April 20 to 29, 1922. Cooperat ...

. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party, holding office during the onset of the Gr ...

helped insure the Pan American women delegates were women of achievement, not trophy wives of diplomats. The conference concluded by forming the Pan-American Association for the Advancement of Women, with Carrie Chapman Catt as president. Cunningham was appointed chair of the Negro Problems Committee.

Politics

Cunningham directed the LWV's 1924 Get Out The Vote Campaign, for which she toured several states. The campaign was her final act as an officer of LWV. Cunningham acceptedEleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

's invitation to join Democratic National Committee (DNC) vice chair Emily Newell Blair

Emily Newell Blair (January 9, 1877 – August 3, 1951) was an American writer, suffragist, feminist, national Democratic Party political leader, and a founder of the League of Women Voters.

Biography

Early life and ancestors

Emily Jane Newel ...

's Democratic Women's Advisory Committee (DWAC). It was authorized by DNC chair Cordell Hull

Cordell Hull (October 2, 1871July 23, 1955) was an American politician from Tennessee and the longest-serving U.S. Secretary of State, holding the position for 11 years (1933–1944) in the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ...

and met in 1924 in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. Eleanor Roosevelt was the committee chair. The DNC platform committee refused to meet with the DWAC, but Cunningham was able to meet with the platform committee as part of the LWV. Watching the platform committee undermine her presentations became a learning curve for Cunningham, who was beginning to believe women needed more involvement in partisan politics.

Former Texas Governor James E. Ferguson, who was forbidden by the articles of impeachment from holding office, put his homemaker wife Miriam A. Ferguson

Miriam Amanda Wallace "Ma" Ferguson (June 13, 1875 – June 25, 1961) was an American politician who served two non-consecutive terms as the governor of Texas: from 1925 to 1927, and from 1933 to 1935. She was the first female governor of Texas, ...

up as the Democratic candidate in the 1924 gubernatorial election. That turn of events prompted Cunningham to support Republican candidate George C. Butte. Cunningham served as chair of the Texas League of Women Voters (TLWV) Committee on Prison Reform. She was also a member of the Texas Committee on Prisons and Prison Labor (CPPL), hoping to reform the Texas practice of incarcerating prisoners as cotton plantation labor. In 1925, CPPL's Elizabeth Speer named Cunningham to chair a committee to present the findings of a National Committee on Prisons and Prison Labor to the state legislature. Governor Miriam Ferguson vetoed the CPPL's recommendation of taking the prisoners off the plantations and housing them in a new facility to be built in Austin.

Emily Newell Blair

Emily Newell Blair (January 9, 1877 – August 3, 1951) was an American writer, suffragist, feminist, national Democratic Party political leader, and a founder of the League of Women Voters.

Biography

Early life and ancestors

Emily Jane Newel ...

was the club's principal founder, and also served it as secretary (1922–1926) and then later as president (1928–1929). Edith Bolling Galt Wilson

Edith Wilson ( Bolling, formerly Galt; October 15, 1872 – December 28, 1961) was the first lady of the United States from 1915 to 1921 and the second wife of President Woodrow Wilson. She married the widower Wilson in December 1915, during hi ...

headed the club's board of governors when it opened formally in 1924.

Running for U.S. Senate

Cunningham ran in the 1928 election to represent the state of Texas in the United States Senate, the first woman in Texas to do so. Her opponent was the incumbent Earle B. Mayfield. Her goal in choosing to run was to elevate the status of women in the electorate. She ran on issues, forsaking the combative style of politics that historically dominated elections. In doing so, she disregarded advice from many, including her long-time ally Alexander Caswell Ellis. Cunningham lost in the state's primary.

Cunningham ran in the 1928 election to represent the state of Texas in the United States Senate, the first woman in Texas to do so. Her opponent was the incumbent Earle B. Mayfield. Her goal in choosing to run was to elevate the status of women in the electorate. She ran on issues, forsaking the combative style of politics that historically dominated elections. In doing so, she disregarded advice from many, including her long-time ally Alexander Caswell Ellis. Cunningham lost in the state's primary.

New Deal

Cunningham was appointed associate editor at the Texas Extension Service in 1930. In 1934, she became acting editor. She was a guest speaker at the 1937 Texas Agricultural Association (TAA) meeting and was a 1938 advisor to the association. She became interested in the link between poverty and poor nutrition, and in 1939 began working for the Agriculture Adjustment Administration (AAA). Cunningham worked in tandem with the Texas Federation of Women's Clubs (TFWC) to advocate bakers enrich flour with basic vitamin and mineral content. She was appointed Senior Specialist of the AAA's Information Division in 1939.McArthur, Smith (2005) pp.154–155,157 She formed the Women's Committee for Economic Policy (WCEP) in 1938. And in 1941 whenLyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

ran as a candidate for the United States Senate, the WCEP had an agreement with him that in exchange for his making freight-rate reform a top priority, they would get out the vote for him. The WCEP also advocated a fully funded teacher retirement system and pensions for needy elderly persons who did not qualify for Social Security. In 1940, Cunningham became chief of the National Defense Advisory Commission Consumer Division's Civic Contracts Unit. Cunningham became frustrated with anti-New Deal elements within the Department of Agriculture and its subsequent gag order on the AAA. She resigned in 1943 and went home to Texas.

1944 Campaign for governor and Texas liberals

After returning home to Texas, Cunningham ran for governor in 1944, to oppose what she believed were GovernorCoke Stevenson

Coke Robert Stevenson (March 20, 1888 – June 28, 1975) was an American politician who served as the 35th governor of Texas from 1941 to 1947. He was the first Texan politician to hold its three highest offices (Speaker of the Texas Hou ...

's behind-the-scenes manipulations to undermine Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's price controls. She was particularly incensed with his cutting pensions for the elderly to balance his state budget. The anti-Roosevelt Democrats in the South conspired to throw the next Presidential election into the House of Representatives. The Texas Regulars, as the group was called in the state, operated at the behest of the oil and gas lobby, as did Stevenson. Cunningham, Bob Eckhardt, John Henry Faulk

John Henry Faulk (August 21, 1913 – April 9, 1990) was an American storyteller and radio show host. His successful lawsuit against the entertainment industry helped to bring an end to the Hollywood blacklist.

Early life

John Henry Faulk wa ...

and other Texas liberals of the time had tried in vain to convince J. Frank Dobie

James Frank Dobie (September 26, 1888 – September 18, 1964) was an American folklorist, writer, and newspaper columnist best known for his many books depicting the richness and traditions of life in rural Texas during the days of the open rang ...

to run against Stevenson. That same group of liberals later formed the 1946 People's Legislative Committee (PLC), to give a voice to the disenfranchised. With little or no funding, Cunningham sold lumber from trees on Fisher Farms to raise money for her filing fee. Liz Carpenter

Mary Elizabeth Sutherland Carpenter (September 1, 1920 – March 20, 2010) was a writer, feminist, reporter, media advisor, speechwriter, political humorist, and public relations expert. As the first woman executive assistant to Vice Presiden ...

served as Cunningham's press secretary. Stevenson was forced to stay in Texas campaigning for re-election, rather than attend the national convention in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

. The 1944 campaign served to meld liberals into a cohesive unit in Texas. Although she lost in the primary, Cunningham did come in second in the nine-candidate race.Sicherman, Green (1986) pp.176,177 At Cunningham's urging, Sarah T. Hughes

Sarah Tilghman Hughes (August 2, 1896 – April 23, 1985) was an American lawyer and federal judge who served on the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas. She is best known as the judge who swore in Lyndon B. Johnson ...

ran for Congress against Joseph Franklin Wilson, losing in a post-primary runoff.

Governor W. Lee O'Daniel

Wilbert Lee "Pappy" O'Daniel (March 11, 1890May 11, 1969) was an American Democratic Party politician from Texas, who came to prominence by hosting a popular radio program. Known for his populist appeal and support of Texas's business commun ...

stacked the University of Texas Board of Regents with Texas Regulars, a practice continued with Stevenson. University president Homer Rainey

Homer Price Rainey (January 19, 1896 – December 19, 1985) was an American college professor, administrator, minister, and politician. He served as the president of several universities, most notably the University of Texas at Austin from 1 ...

was fired in 1944 for his continued conflicts with the regents over their firing of professors. Cunningham formed the Women's Committee for Educational Freedom (WCEF) in 1945 as a call to arms over practices of the university regents. Rainey ran for governor in 1946, but lost to Beauford H. Jester.

Shivercrats and final years

A farm labor organization named the Texas Social and Legislative Conference (TSLC) was primarily the concept of Cunningham and Alexander Caswell Ellis. They worked to create a coalition of parties with a vested interest in New Deal policies. As a result of their efforts, James Carey of theCongress of Industrial Organizations

The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was a federation of unions that organized workers in industrial unions in the United States and Canada from 1935 to 1955. Originally created in 1935 as a committee within the American Federation of ...

, Frank Overturf of the Texas Farmer's Union and James Patton of the National Farmers Union formed the TSLC in February 1944. Cunningham continued to be involved with the Democratic Party, supporting Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

in 1948.

When Texas Governor Beauford H. Jester unexpectedly died in office July 11, 1949, then Lieutenant Governor Allan Shivers

Robert Allan Shivers (; October 5, 1907 – January 14, 1985) was an American politician who served as the 37th governor of Texas. Shivers was a leader of the Texas Democratic Party during the turbulent 1940s and 1950s and developed the lieutena ...

ascended to the governor's mansion. Shivers controlled the wing of the Texas Democratic Party that were Dixiecrat

The States' Rights Democratic Party (whose members are often called the Dixiecrats) was a short-lived segregationist political party in the United States, active primarily in the South. It arose due to a Southern regional split in opposition t ...

s, or States' Rights, holdovers. An internal contest for the party played out, with Shivers intent on delivering the state of Texas to Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

in 1952. Those who aligned themselves with Shivers were called Shivercrats. At the state convention, the Shivercrats controlled the party and influenced the Democrats to vote Republican for Eisenhower, rather than the Democratic party standard bearer Adlai Stevenson. Cunningham and Lillian Collier ran the Texas Women for Stevenson organization out of Austin. In 1953, Cunningham instituted the Texas Democratic Women's State Committee (TDSW), with a constitution that required individual member support for the federal level of the Democratic party. The organization drew the disenfranchised of the state Democrats, the minorities and liberals who were otherwise shut out by the Shivercrats. Ralph Yarborough

Ralph Webster Yarborough (June 8, 1903 – January 27, 1996) was an American politician and lawyer. He was a Texas Democratic politician who served in the United States Senate from 1957 to 1971 and was a leader of the progressive wing of his p ...

was supported by the TDSW when he ran against Shivers in 1952 and 1954.

Cunningham had penned her "Countryside and Town" column in the ''State Observer'' since 1944, and was convinced the liberals needed media focus on their platforms and activities. The paper was put up for sale in 1954 by publisher Paul Holcomb. She offered to mortgage Fisher Farms to buy the paper, but Holcomb refused to sell to her. She and Lillian Collier arranged with Franklin Jones of the ''East Texas Democrat'' to merge the two papers. Frankie Carter Randolph provided the funding, and the paper was renamed ''The Texas Observer

''The Texas Observer'' (also known as the ''Observer'') is an American magazine with a liberal political outlook. The ''Observer'' is published bimonthly by a 501(c)(3)

The Democrats held statewide events in 1958 to honor Cunningham's contributions. The Texas Democrats sent Lyndon Johnson as head of the Texas faction to the 1960 Democratic National Convention. The TDSW ran Cunningham in the 1960 Texas primary in a Favorite Daughter campaign, sidestepping any support for either Shivers or Johnson. Cunningham was an invited guest to the inauguration of President

Woman's National Democratic ClubLeague of Women Voters-National OfficeLeague of Women Voters of Texas

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cunningham, Minnie Fisher 1882 births 1964 deaths American democracy activists American feminists Methodists from Texas American suffragists History of women in Texas History of women's rights in the United States People from New Waverly, Texas Texas Democrats Women in Texas politics Clubwomen Texas suffrage Members of the League of Women Voters

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

, a nod from Kennedy for her assistance in helping him carry the predominantly Republican Walker County in 1960. The campaign headquarters she had set up for Kennedy in New Waverly was financed by the sale of used clothing.

Personal life and death

Minnie Fisher married insurance executive Beverly Jean (B.J.) Cunningham on November 27, 1902. Her husband was elected County Attorney in 1904. In 1905 they relocated to Houston where her husband managed a branch office ofTravelers Insurance

The Travelers Companies, Inc., commonly known as Travelers, is an American insurance company. It is the second-largest writer of U.S. commercial property casualty insurance, and the sixth-largest writer of U.S. personal insurance through indepen ...

. Two years later, they moved to Galveston to facilitate his management of American National Insurance Company

American National Insurance Company (ANICO) is a major American insurance corporation based in Galveston, Texas. The company and its subsidiaries operate in all 50 U.S. states and Puerto Rico.

Company description

American National was founded in ...

. B.J. died March 20, 1928.

Her father Horatio White Fisher died in 1906. After his death, Fisher's widow Sallie lived with her daughter and son-in-law, Ella and Richard M. Traylor at Fisher Farms. Shortly after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, Minnie Cunningham moved in with the Traylors to become Sallie's primary caregiver. In between jobs, Cunningham would repeatedly return to Texas to be a full-time caregiver for her mother. Sallie Fisher died in 1930. Ella Traylor died in 1944. Richard M. Traylor died in 1962.

Although she continued to be active, Cunningham had declining health in her final years. She suffered from heart problems and broke her hip in 1964. On December 9, 1964, Minnie Fisher Cunningham died of congestive heart failure. She was buried at the Hardy Cemetery in New Waverly, Texas.McArthur, Smith (2005) pp.202,203

Notes

References

* *} *External links

Woman's National Democratic Club

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cunningham, Minnie Fisher 1882 births 1964 deaths American democracy activists American feminists Methodists from Texas American suffragists History of women in Texas History of women's rights in the United States People from New Waverly, Texas Texas Democrats Women in Texas politics Clubwomen Texas suffrage Members of the League of Women Voters