Micronesia Navigation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Micronesian navigation techniques are those navigation skills used for thousands of years by the navigators who voyaged between the thousands of small islands in the western

Micronesian navigation techniques are those navigation skills used for thousands of years by the navigators who voyaged between the thousands of small islands in the western

Mau Piailug was the best-known teacher of traditional, non-instrument wayfinding methods for open-ocean voyaging. He was a master

Mau Piailug was the best-known teacher of traditional, non-instrument wayfinding methods for open-ocean voyaging. He was a master

The positions of the stars helped guide voyages. Stars, as opposed to planets, hold fixed celestial positions year-round, changing only their rising time with the seasons. Each star has a specific declination, and can give a bearing for navigation as it rises or sets.

For navigators near the equator, (as navigators sailing between the islands of Micronesia),

The positions of the stars helped guide voyages. Stars, as opposed to planets, hold fixed celestial positions year-round, changing only their rising time with the seasons. Each star has a specific declination, and can give a bearing for navigation as it rises or sets.

For navigators near the equator, (as navigators sailing between the islands of Micronesia),

Navigators could also observe the direction of the wave and swell formations to navigate caused by islands. Many of the habitable areas of the Pacific Ocean are groups of islands (or atolls) in chains hundreds of kilometres long. Island chains have predictable effects on waves and currents. Navigators who lived within a group of islands would learn the effect various islands had on the swell shape, direction, and motion, and would have been able to correct their path accordingly. Even when they arrived in the vicinity of an unfamiliar chain of islands, they may have been able to detect signs similar to those of their home.

The energy transferred from the wind to the sea produces wind waves. The waves that are created when the energy travels down away from the source area (like ripples) are known as swell. When the winds are strong at the source area, the swell is larger. The longer the wind blows, the longer the swell lasts. Because the swells of the ocean can remain consistent for days, navigators relied on them to carry their canoe in a straight line from one house (or point) on the star compass to the opposite house of the same name. Navigators were not always able to see stars; because of this, they relied on the swells of the ocean. Swell patterns are a much more reliable method of navigation than waves, which are determined by the local winds. Swells move in a straight direction which makes it easier for the navigator to determine whether the canoe is heading in the correct direction.

The people of the

Navigators could also observe the direction of the wave and swell formations to navigate caused by islands. Many of the habitable areas of the Pacific Ocean are groups of islands (or atolls) in chains hundreds of kilometres long. Island chains have predictable effects on waves and currents. Navigators who lived within a group of islands would learn the effect various islands had on the swell shape, direction, and motion, and would have been able to correct their path accordingly. Even when they arrived in the vicinity of an unfamiliar chain of islands, they may have been able to detect signs similar to those of their home.

The energy transferred from the wind to the sea produces wind waves. The waves that are created when the energy travels down away from the source area (like ripples) are known as swell. When the winds are strong at the source area, the swell is larger. The longer the wind blows, the longer the swell lasts. Because the swells of the ocean can remain consistent for days, navigators relied on them to carry their canoe in a straight line from one house (or point) on the star compass to the opposite house of the same name. Navigators were not always able to see stars; because of this, they relied on the swells of the ocean. Swell patterns are a much more reliable method of navigation than waves, which are determined by the local winds. Swells move in a straight direction which makes it easier for the navigator to determine whether the canoe is heading in the correct direction.

The people of the

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contine ...

in the subregion

A subregion is a part of a larger region or continent and is usually based on location. Cardinal directions, such as south are commonly used to define a subregion.

United Nations subregions

The Statistics Division of the United Nations (UN) ...

of Oceania

Oceania (, , ) is a region, geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern Hemisphere, Eastern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of ...

, that is commonly known as Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

. These voyagers used wayfinding techniques such as the navigation by the stars, and observations of birds, ocean swells, and wind patterns, and relied on a large body of knowledge from oral tradition.

These navigation techniques continued to be held by Polynesian navigators and navigators from the Santa Cruz Islands. The re-creations of Polynesian voyaging in the late 20th century used traditional stellar navigational methods that had remained in everyday use in the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

.

Early voyaging

Based on the current scientific consensus, the Micronesians are considered, by linguistic, archaeological, and human genetic evidence, to be a subset of the sea-migratingAustronesian people

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and Madagascar that speak Austr ...

, who include the Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

n people and the Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, ...

n people. Austronesians were the first people to invent oceangoing sailing technologies (notably double-hulled sailing canoes, outrigger boat

Outrigger boats are various watercraft featuring one or more lateral support floats known as outriggers, which are fastened to one or both sides of the main hull. They can range from small dugout canoes to large plank-built vessels. Outrigger ...

s, lashed-lug

Lashed-lug boats are ancient boat-building techniques of the Austronesian peoples. It is characterized by the use of sewn holes and later dowels ("treenails") to stitch planks edge-to-edge onto a dugout keel and solid carved wood pieces that fo ...

boat building

Boat building is the design and construction of boats and their systems. This includes at a minimum a hull, with propulsion, mechanical, navigation, safety and other systems as a craft requires.

Construction materials and methods

Wood

W ...

, and the crab claw sail

The crab claw sail is a fore-and-aft triangular sail with spars along upper and lower edges. The crab claw sail was first developed by the Austronesian peoples some time around 1500 BC. It is used in many traditional Austronesian cultures in Isl ...

), which enabled their rapid dispersal into the islands of the Indo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is a vast biogeographic region of Earth.

In a narrow sense, sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific or Indo-Pacific Asia, it comprises the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and the ...

. From 2000 BCE they assimilated (or were assimilated by) the earlier populations on the islands in their migration pathway.

The Mariana Islands were first settled around 1500 to 1400 BCE by migrants departing from the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. This was followed by a second migration from the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

during the first millennium CE, and a third migration from Island Southeast Asia (likely the Philippines or eastern Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

) by 900 CE.

People from the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

had regular contact with the Chamorro people

The Chamorro people (; also CHamoru) are the indigenous people of the Mariana Islands, politically divided between the United States territory of Guam and the encompassing Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands in Micronesia. Today, si ...

of the Marianas Islands, as well as rarer voyages into the eastern islands of the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

.

20th Century navigators

Mau Piailug was the best-known teacher of traditional, non-instrument wayfinding methods for open-ocean voyaging. He was a master

Mau Piailug was the best-known teacher of traditional, non-instrument wayfinding methods for open-ocean voyaging. He was a master navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

from the Carolinian island of Satawal

Satawal is a solitary coral atoll of one island with about 500 people on just over 1 km2 located in the Caroline Islands in the Pacific Ocean. It forms a legislative district in Yap State in the Federated States of Micronesia. Satawal is t ...

. He earned the title of master navigator (''palu'') by the age of eighteen in 1950; which involved the sacred

Sacred describes something that is dedicated or set apart for the service or worship of a deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or godd ...

initiation ritual known as ''Pwo {{for, Pwo languages, Pwo languages

Pwo is a sacred initiation ritual, in which students of traditional navigation in the Caroline Islands in Micronesia become navigators (''palu'') and are initiated in the associated secrets. Many islanders in th ...

''. As he neared middle age, he grew concerned that the practice of navigation in Satawal would disappear as his people became acculturated to Western values. In the hope that the navigational tradition would be preserved for future generations, Mau shared his knowledge with the Polynesian Voyaging Society

The Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS) is a non-profit research and educational corporation based in Honolulu, Hawaii. PVS was established to research and perpetuate traditional Polynesian voyaging methods. Using replicas of traditional double-hul ...

(PVS). With Mau's help, PVS recreated and tested lost Hawaiian navigational techniques on the '' Hōkūle‘a'', a modern reconstruction of a double-hulled Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only ...

an voyaging canoe

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the term ...

.

Hipour was a master navigator from the navigational school of Weriyeng and the island of Puluwat. which greatly reinvigorated interest in traditional Pacific celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space (or on the surface ...

. In 1969, Hipour accompanied David Henry Lewis on his ketch ''Isbjorn'' from Puluwat in Chuuk to Saipan

Saipan ( ch, Sa’ipan, cal, Seipél, formerly in es, Saipán, and in ja, 彩帆島, Saipan-tō) is the largest island of the Northern Mariana Islands, a commonwealth of the United States in the western Pacific Ocean. According to 2020 est ...

in the Northern Mariana Islands

The Northern Mariana Islands, officially the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI; ch, Sankattan Siha Na Islas Mariånas; cal, Commonwealth Téél Falúw kka Efáng llól Marianas), is an unincorporated territory and commonwe ...

, and back, using traditional navigation techniques; a distance of approximately each way.

In April 1970, Repunglug and Repunglap, half-brothers, navigated from Satawal to Saipan in a traditional Carolinian outrigger canoe, which was approximately long, and equipped with a canvas sail. This voyage was understood on Satawal to be the first time in the 20th century that a traditional canoe had made the voyage to Saipan. While they used a small boat compass, they relied on their knowledge of traditional stellar navigation and wave patterns to sail approximately to West Fayu, where they waited for favourable winds before continuing on the voyage to Saipan. They later made the return journey to Satawal.

In the early 1970's there were at least 17 men who could serve as a master navigator (''palu'') for voyages to the Marianas. They include Sautan on Elato; Orupi, a Satawal man residing on Lamotrek; Ikegun, Epaimai, Repunglug, Repunglap, and Mau Piailug from Satawal

Satawal is a solitary coral atoll of one island with about 500 people on just over 1 km2 located in the Caroline Islands in the Pacific Ocean. It forms a legislative district in Yap State in the Federated States of Micronesia. Satawal is t ...

; Ikuliman, Ikefie, Manipi, Rapwi, Faipiy, Faluta, Filewa and Hipour, all from Puluwat; Yaitiluk from Pulap, and Amanto from Tamatam. There were also six or seven apprentice navigators learning the art of traditional navigation on Satawal, including Epoumai and Repunglug's son Olakiman.

Navigational techniques

The Carolinian navigation system, used by Mau Piailug, relies on navigational clues using the Sun and stars, winds and clouds, seas and swells, observing the flight path of birds, and the patterns ofbioluminescence

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some fungi, microorganisms including some ...

that indicated the direction in which islands were located, was acquired through rote learning passed down through teachings in the oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985 ...

.

Once they had arrived fairly close to a destination island, the navigator would have been able to pinpoint its location by sightings of land-based birds, the cloud formations that form over islands, as well as the reflections of shallow water made on the undersides of clouds. Subtle differences in the colour of the sky also could be recognised as resulting from the presence of lagoons or shallow waters, as deep water was a poor reflector of light while the lighter colour of the water of lagoons and shallow waters could be identified in the reflection in the sky.

These wayfinding navigation technique relies heavily on constant observation and memorization. Navigators have to memorize where they have sailed from in order to know where they are. The sun was the main guide for navigators because they could follow its exact points as it rose and set. Once the sun had set they would use the rising and setting points of the stars. When there were no stars because of a cloudy night or during daylight, a navigator would use the winds and swells as guides.

Navigation by the stars

The positions of the stars helped guide voyages. Stars, as opposed to planets, hold fixed celestial positions year-round, changing only their rising time with the seasons. Each star has a specific declination, and can give a bearing for navigation as it rises or sets.

For navigators near the equator, (as navigators sailing between the islands of Micronesia),

The positions of the stars helped guide voyages. Stars, as opposed to planets, hold fixed celestial positions year-round, changing only their rising time with the seasons. Each star has a specific declination, and can give a bearing for navigation as it rises or sets.

For navigators near the equator, (as navigators sailing between the islands of Micronesia), celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space (or on the surface ...

is simplified, given that the whole celestial sphere is exposed. Any star that passes through the zenith

The zenith (, ) is an imaginary point directly "above" a particular location, on the celestial sphere. "Above" means in the vertical direction ( plumb line) opposite to the gravity direction at that location ( nadir). The zenith is the "high ...

(overhead) moves along the celestial equator, the basis of the equatorial coordinate system. Voyagers would set a heading by a star near the horizon, switching to a new one once the first rose too high. A specific sequence of stars would be memorized for each route.

Navigating by the stars requires knowledge of when particular stars, as they rotated through the night sky, would pass over the island to which the voyagers were sailing. The technique of "sailing down the latitude" was used.

That is, knowledge that the movement of stars over different islands followed a similar pattern, (by recognising that different islands have a similar relationship to the night sky) provided the navigators with a sense of latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north po ...

, so that they could sail with the prevailing wind, before turning east or west to reach the island that was their destination.

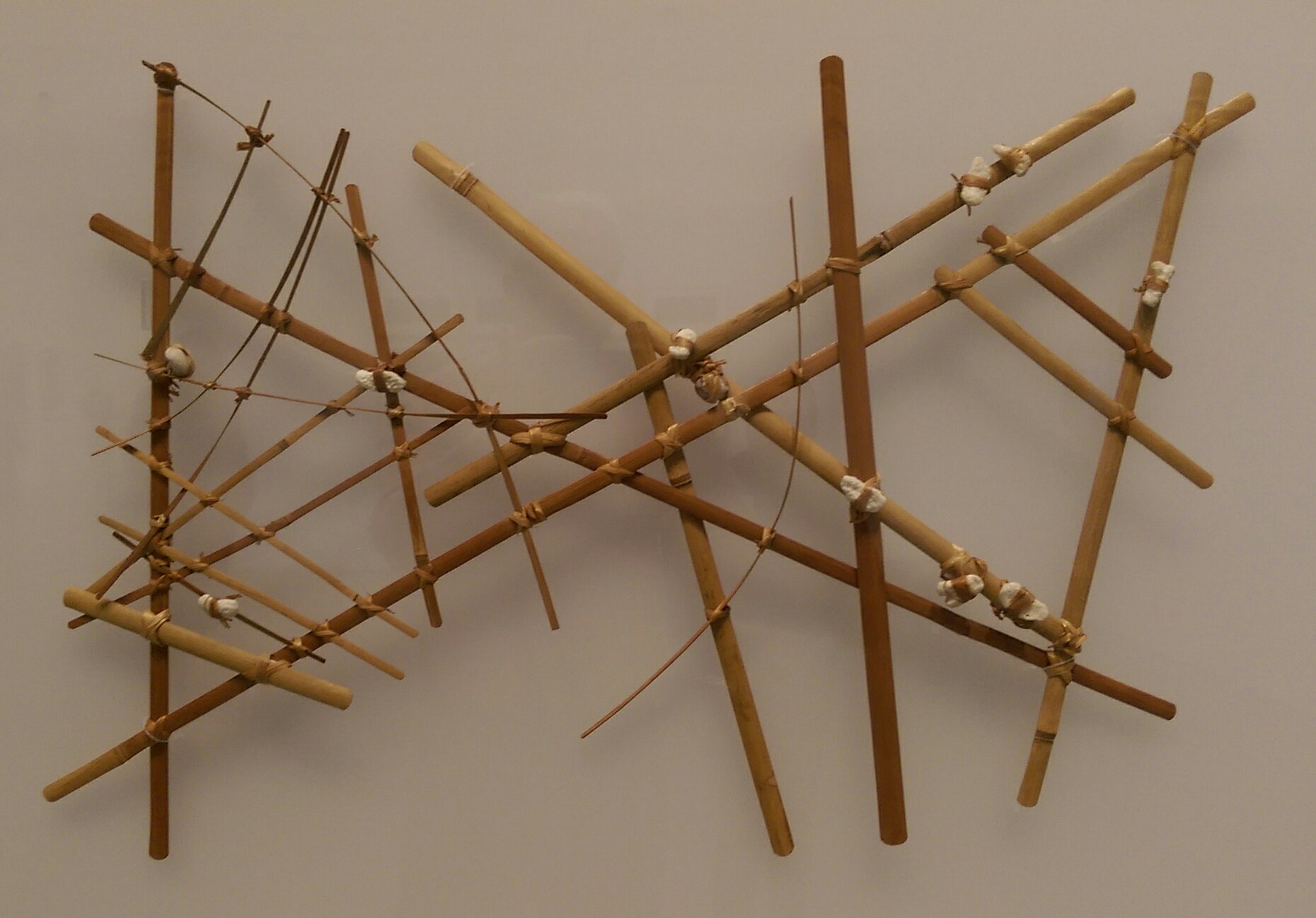

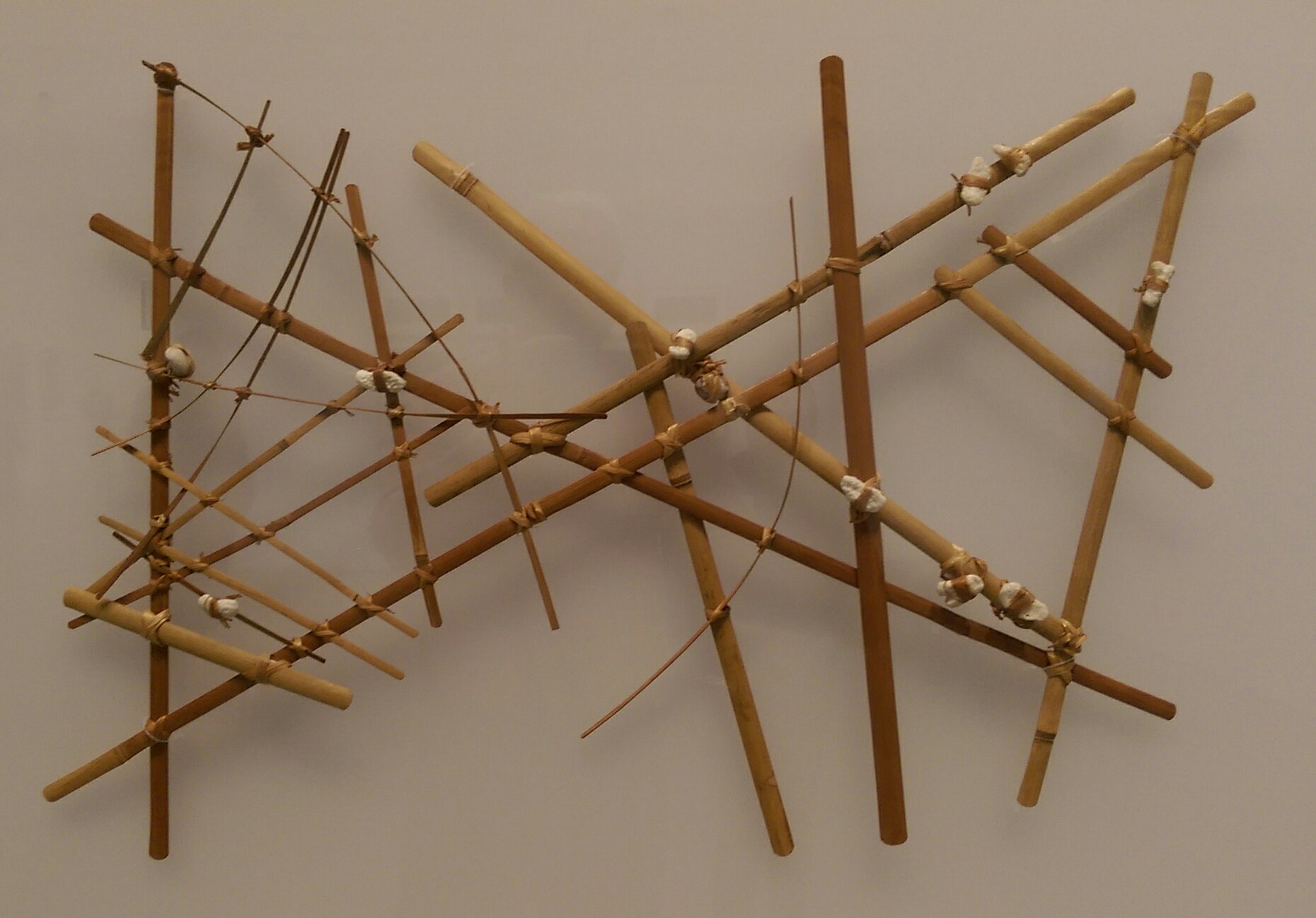

Recording wave and swell formation in navigational devices

Navigators could also observe the direction of the wave and swell formations to navigate caused by islands. Many of the habitable areas of the Pacific Ocean are groups of islands (or atolls) in chains hundreds of kilometres long. Island chains have predictable effects on waves and currents. Navigators who lived within a group of islands would learn the effect various islands had on the swell shape, direction, and motion, and would have been able to correct their path accordingly. Even when they arrived in the vicinity of an unfamiliar chain of islands, they may have been able to detect signs similar to those of their home.

The energy transferred from the wind to the sea produces wind waves. The waves that are created when the energy travels down away from the source area (like ripples) are known as swell. When the winds are strong at the source area, the swell is larger. The longer the wind blows, the longer the swell lasts. Because the swells of the ocean can remain consistent for days, navigators relied on them to carry their canoe in a straight line from one house (or point) on the star compass to the opposite house of the same name. Navigators were not always able to see stars; because of this, they relied on the swells of the ocean. Swell patterns are a much more reliable method of navigation than waves, which are determined by the local winds. Swells move in a straight direction which makes it easier for the navigator to determine whether the canoe is heading in the correct direction.

The people of the

Navigators could also observe the direction of the wave and swell formations to navigate caused by islands. Many of the habitable areas of the Pacific Ocean are groups of islands (or atolls) in chains hundreds of kilometres long. Island chains have predictable effects on waves and currents. Navigators who lived within a group of islands would learn the effect various islands had on the swell shape, direction, and motion, and would have been able to correct their path accordingly. Even when they arrived in the vicinity of an unfamiliar chain of islands, they may have been able to detect signs similar to those of their home.

The energy transferred from the wind to the sea produces wind waves. The waves that are created when the energy travels down away from the source area (like ripples) are known as swell. When the winds are strong at the source area, the swell is larger. The longer the wind blows, the longer the swell lasts. Because the swells of the ocean can remain consistent for days, navigators relied on them to carry their canoe in a straight line from one house (or point) on the star compass to the opposite house of the same name. Navigators were not always able to see stars; because of this, they relied on the swells of the ocean. Swell patterns are a much more reliable method of navigation than waves, which are determined by the local winds. Swells move in a straight direction which makes it easier for the navigator to determine whether the canoe is heading in the correct direction.

The people of the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Internati ...

have a history of using stick charts, to serve as spatial representations of islands and the conditions around them; with the curvature and meeting-points of the coconut ribs indicating the wave motion that was the result of islands standing in the path of the prevailing wind and the run of the waves. The charts represented major ocean swell patterns and the ways the islands disrupted those patterns, typically determined by sensing disruptions in ocean swells by islands during sea navigation. Most stick charts were made from the midribs of coconut fronds that were tied together to form an open framework. Island locations were represented by shells tied to the framework, or by the lashed junction of two or more sticks. The threads represented prevailing ocean surface wave

In fluid dynamics, a wind wave, water wave, or wind-generated water wave, is a surface wave that occurs on the free surface of bodies of water as a result from the wind blowing over the water surface. The contact distance in the direction o ...

-crests and directions they took as they approached islands and met other similar wave-crests formed by the ebb and flow of breakers. Individual charts varied so much in form and interpretation that the individual navigator who made the chart was the only person who could fully interpret and use it. The use of stick charts ended after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

when new electronic technologies made navigation more accessible and travel among islands by canoe lessened.

Vessels

* Wa (watercraft) * Sakman * baurua * walapSources

*. *. *References

{{Trade route 2 Navigation History of navigation Prehistoric migrations Cartography by country Micronesian culture Traditional knowledge