Michael Murray Hordern on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Michael Murray Hordern

"Hordern, Michael Murray (1911–1995)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, online edition, May 2009, accessed 22 July 2015 was an English actor whose career spanned nearly 60 years. He is best known for his

Hordern was born 3 October 1911 at

Hordern was born 3 October 1911 at  Four years after the birth of Peter, a pregnant Margaret returned to England, where Michael Hordern, her third son, was born. Still stationed abroad, Edward was promoted to the rank of

Four years after the birth of Peter, a pregnant Margaret returned to England, where Michael Hordern, her third son, was born. Still stationed abroad, Edward was promoted to the rank of

''

In mid-1937 the theatre proprietor Ronald Russell offered Hordern a part in his

In mid-1937 the theatre proprietor Ronald Russell offered Hordern a part in his

In 1940, after a minor role in ''Without the Prince'' at the Whitehall Theatre, Hordern played the small, uncredited part of a BBC official alongside James Hayter in Arthur Askey's comedy film ''

In 1940, after a minor role in ''Without the Prince'' at the Whitehall Theatre, Hordern played the small, uncredited part of a BBC official alongside James Hayter in Arthur Askey's comedy film ''

by Michael Billington. ''The Guardian'', 25 October 2002, accessed 21 August 2015. The play proved popular with audiences, but not so with theatrical commentators. Hordern liked the piece, calling it "bitter and interesting",Hordern, p. 90. but the press, who extensively reported on the competition throughout each stage, thought differently and condemned it for winning. This infuriated the actors

Hordern cited ''Saint's Day''s negative publicity as having done his career "the power of good" as it brought him to the attention of the director

Hordern cited ''Saint's Day''s negative publicity as having done his career "the power of good" as it brought him to the attention of the director

Hordern's contract at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre lasted until mid-1952, and on its expiration, he secured a position within Michael Benthall's theatrical company at

Hordern's contract at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre lasted until mid-1952, and on its expiration, he secured a position within Michael Benthall's theatrical company at

the Old Vic theatre programme: 1953/54 season, accessed 25 August 2015. The lead character initially went to an unknown and inexperienced young actor, but the part was re-cast with Hordern in the role.Hordern, p. 100. Hordern described ''King John'' as being "a difficult play in the sense that it has no common purpose or apparent theme". Simultaneously to this, he was commuting back to

In early 1955 Hordern was asked by the British theatre manager and producer

In early 1955 Hordern was asked by the British theatre manager and producer

Hordern viewed the 1950s as a good decade to appear in film, although he did not then particularly care for the medium. Writing in 1993 he said: "With cinema one has to leap into battle fully armed. From the start of the film the character has to be pinned down like a butterfly on a board. One does not always get this right, of course, sometimes starting at the beginning of shooting a film on a comedic level that cannot be sustained."Hordern, p. 165. He disliked his physical appearance, which he found to be "repulsive", and as a result loathed watching back his performances. He preferred radio because the audience only heard his voice, which he then considered his best attribute. Another reason was his recognition of the differences between his sense of personal achievement within a theatre compared to that on a film set: "You get a certain sort of satisfaction in delivering what the director wants of you, but the chances of being emotionally involved are slim." He acknowledged his good ability at learning lines, something which he found to be especially helpful for learning film scripts which frequently changed. He enjoyed the challenge of earning as much value as possible out of a scene and revelled in being able to hit "the right mark for the camera". With the experience of ''Nina'' still fresh in his mind, Hordern took a break from the stage and decided to concentrate on his film career.Hordern, p. 108.

Hordern was appearing in three to four films a year by 1953, a count that increased as the decade progressed. In 1956 he took a leading part in '' The Spanish Gardener'' for which he spent many months filming in southern Spain alongside

Hordern viewed the 1950s as a good decade to appear in film, although he did not then particularly care for the medium. Writing in 1993 he said: "With cinema one has to leap into battle fully armed. From the start of the film the character has to be pinned down like a butterfly on a board. One does not always get this right, of course, sometimes starting at the beginning of shooting a film on a comedic level that cannot be sustained."Hordern, p. 165. He disliked his physical appearance, which he found to be "repulsive", and as a result loathed watching back his performances. He preferred radio because the audience only heard his voice, which he then considered his best attribute. Another reason was his recognition of the differences between his sense of personal achievement within a theatre compared to that on a film set: "You get a certain sort of satisfaction in delivering what the director wants of you, but the chances of being emotionally involved are slim." He acknowledged his good ability at learning lines, something which he found to be especially helpful for learning film scripts which frequently changed. He enjoyed the challenge of earning as much value as possible out of a scene and revelled in being able to hit "the right mark for the camera". With the experience of ''Nina'' still fresh in his mind, Hordern took a break from the stage and decided to concentrate on his film career.Hordern, p. 108.

Hordern was appearing in three to four films a year by 1953, a count that increased as the decade progressed. In 1956 he took a leading part in '' The Spanish Gardener'' for which he spent many months filming in southern Spain alongside

CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(3 October 19112 May 1995)Morley, Sheridan"Hordern, Michael Murray (1911–1995)"

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004, online edition, May 2009, accessed 22 July 2015 was an English actor whose career spanned nearly 60 years. He is best known for his

Shakespearean

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

roles, especially that of King Lear

''King Lear'' is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare.

It is based on the mythological Leir of Britain. King Lear, in preparation for his old age, divides his power and land between two of his daughters. He becomes destitute and insane an ...

, which he played to much acclaim on stage in Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon (), commonly known as just Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-we ...

in 1969 and London in 1970. He then successfully assumed the role on television five years later. He often appeared in film, rising from a bit part

In acting, a bit part is a role in which there is direct interaction with the principal actors and no more than five lines of dialogue, often referred to as a five-or-less or under-five in the United States, or under sixes in British television, ...

actor in the late 1930s to a member of the main cast; by the time of his death he had appeared in nearly 140 cinema roles. His later work was predominantly in television and radio.

Born in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire

Berkhamsted ( ) is a historic market town in Hertfordshire, England, in the River Bulbourne, Bulbourne valley, north-west of London. The town is a civil parishes in England, civil parish with a town council within the borough of Dacorum which ...

, into a family with no theatrical connections, Hordern was educated at Windlesham House School

Windlesham House School is an independent boarding and day school for boys and girls aged 4 to 13 on the South Downs, in Pulborough, West Sussex, England. It was founded in 1837 by Charles Robert Malden and was the first boys' preparatory school ...

in Pulborough

Pulborough is a large village and civil parish in the Horsham district of West Sussex, England, with some 5,000 inhabitants. It is located almost centrally within West Sussex and is south west of London. It is at the junction of the north–south ...

, West Sussex

West Sussex is a county in South East England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the shire districts of Adur, Arun, Chichester, Horsham, and Mid Sussex, and the boroughs of Crawley and Worthing. Covering an ar ...

, where he became interested in drama. He went on to Brighton College

Brighton College is an independent, co-educational boarding and day school for boys and girls aged 3 to 18 in Brighton, England. The school has three sites: Brighton College (the senior school, ages 11 to 18); Brighton College Preparatory Sc ...

where his interest in the theatre developed. After leaving the college he joined an amateur dramatics

An amateur () is generally considered a person who pursues an avocation independent from their source of income. Amateurs and their pursuits are also described as popular, informal, self-taught, user-generated, DIY, and hobbyist.

History

Hist ...

company, and came to the notice of several influential Shakespearean directors who cast him in minor roles in ''Othello

''Othello'' (full title: ''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'') is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare, probably in 1603, set in the contemporary Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573) fought for the control of the Island of Cypru ...

'' and ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

''. During the Second World War he served on HMS ''Illustrious'' where he reached the rank of lieutenant commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

. Upon his demobilisation

Demobilization or demobilisation (see spelling differences) is the process of standing down a nation's armed forces from combat-ready status. This may be as a result of victory in war, or because a crisis has been peacefully resolved and militar ...

he resumed his acting career and made his television debut, becoming a reliable bit-part actor in many films, particularly in the war film

War film is a film genre concerned with warfare, typically about naval, air, or land battles, with combat scenes central to the drama. It has been strongly associated with the 20th century. The fateful nature of battle scenes means that war fi ...

genre.

Hordern came to prominence in the early 1950s when he took part in a theatrical competition at the Arts Theatre

The Arts Theatre is a theatre in Great Newport Street, in Westminster, Central London.

History

It opened on 20 April 1927 as a members-only club for the performance of unlicensed plays, thus avoiding theatre censorship by the Lord Chamberl ...

in London. There, he impressed Glen Byam Shaw

Glencairn Alexander "Glen" Byam Shaw, CBE (13 December 1904 – 29 April 1986) was an English actor and theatre director, known for his dramatic productions in the 1950s and his operatic productions in the 1960s and later.

In the 1920s and 1930s ...

who secured the actor a season-long contract at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre

The Royal Shakespeare Theatre (RST) (originally called the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre) is a grade II* listed 1,040+ seat thrust stage theatre owned by the Royal Shakespeare Company dedicated to the English playwright and poet William Shakespea ...

where he played major parts, including Caliban

Caliban ( ), son of the witch Sycorax, is an important character in William Shakespeare's play '' The Tempest''.

His character is one of the few Shakespearean figures to take on a life of its own "outside" Shakespeare's own work: as Russell ...

in '' The Tempest'', Jaques Jaques is a given name and surname, a variant of Jacques.

People with the given name Jaques

* Jaques Bagratuni (1879-1943), Armenian prince

* Jaques Bisan (b. 1993) Beninese footballer

* Jaques Étienne Gay (1786-1864) Swiss-French botanist

* Jaq ...

in ''As You Like It

''As You Like It'' is a pastoral comedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written in 1599 and first published in the First Folio in 1623. The play's first performance is uncertain, though a performance at Wilton House in 1603 has b ...

'', and Sir Politick Would-Be in Ben Jonson's comedy ''Volpone

''Volpone'' (, Italian for "sly fox") is a comedy play by English playwright Ben Jonson first produced in 1605–1606, drawing on elements of city comedy and beast fable. A merciless satire of greed and lust, it remains Jonson's most-perform ...

''. The following season Hordern joined Michael Benthall's company at the Old Vic

The Old Vic is a 1,000-seat, nonprofit organization, not-for-profit producing house, producing theatre in Waterloo, London, Waterloo, London, England. Established in 1818 as the Royal Coburg Theatre, and renamed in 1833 the Royal Victoria Th ...

where, among other parts, he played Polonius

Polonius is a character in William Shakespeare's play ''Hamlet''. He is chief counsellor of the play's ultimate villain, Claudius, and the father of Laertes and Ophelia. Generally regarded as wrong in every judgment he makes over the course of ...

in ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'', and the title role in ''King John King John may refer to:

Rulers

* John, King of England (1166–1216)

* John I of Jerusalem (c. 1170–1237)

* John Balliol, King of Scotland (c. 1249–1314)

* John I of France (15–20 November 1316)

* John II of France (1319–1364)

* John I o ...

''. In 1957 he won a best actor

Best Actor is the name of an award which is presented by various film, television and theatre organizations, festivals, and people's awards to leading actors in a film, television series, television film or play.

The term most often refers to th ...

award at that year's British Academy Television Awards

The BAFTA TV Awards, or British Academy Television Awards are presented in an annual award show hosted by the BAFTA. They have been awarded annually since 1955.

Background

The first-ever Awards, given in 1955, consisted of six categories. Until ...

for his role as the barrister in John Mortimer's courtroom drama ''The Dock Brief

''The Dock Brief'' (US title ''Trial and Error'') is a 1962 black-and-white British legal satire directed by James Hill, starring Peter Sellers and Richard Attenborough, and based on the play of the same name written by John Mortimer (creator o ...

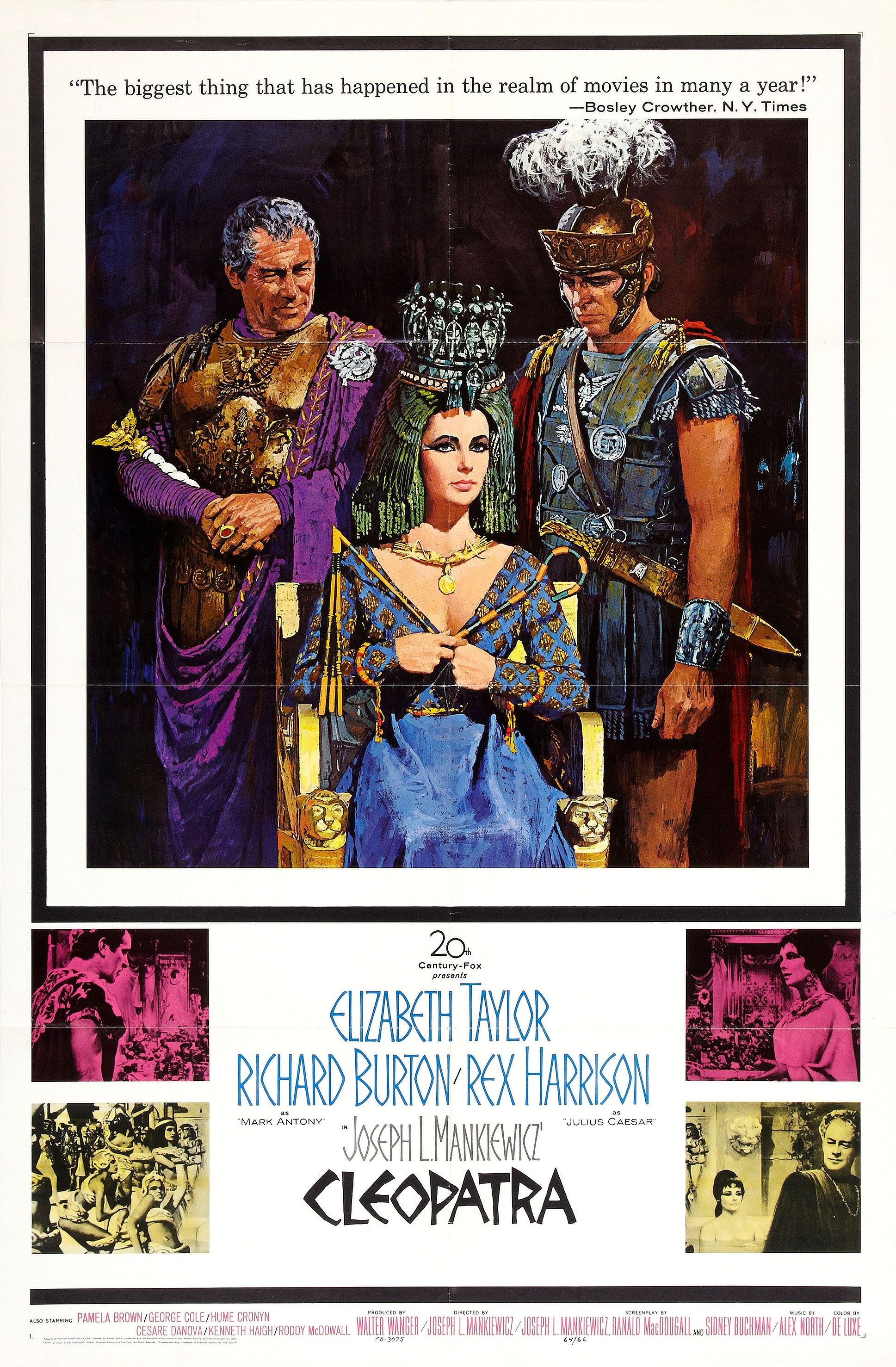

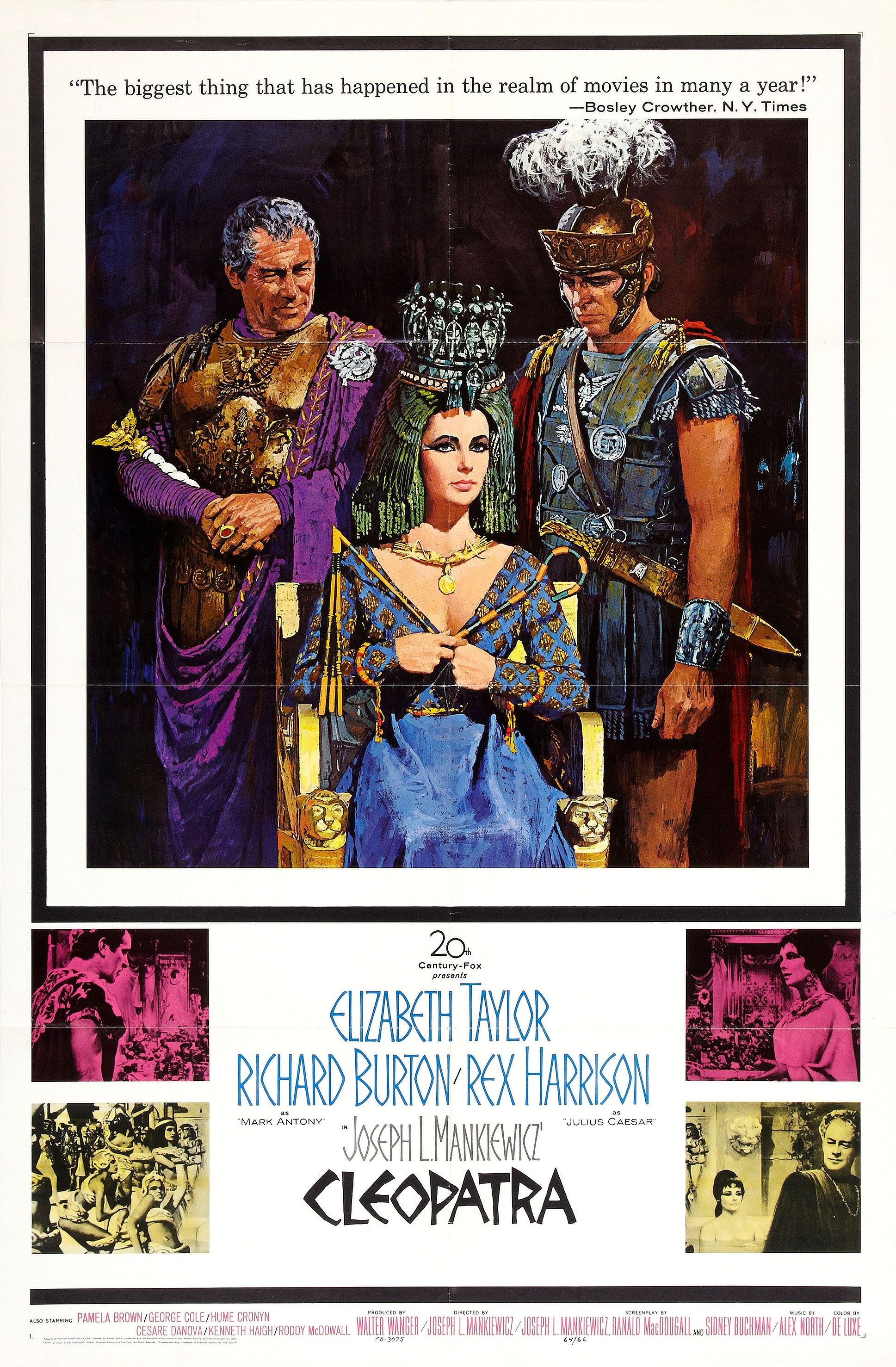

''. Along with his theatrical responsibilities Hordern had regular supporting roles in various films including ''Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler.She was also a ...

'' (1963), and ''A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum

''A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum'' is a musical with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim and book by Burt Shevelove and Larry Gelbart.

Inspired by the farces of the ancient Roman playwright Plautus (254–184 BC), specifica ...

'' (1966).

In the late 1960s Hordern met the British theatre director Jonathan Miller

Sir Jonathan Wolfe Miller CBE (21 July 1934 – 27 November 2019) was an English theatre and opera director, actor, author, television presenter, humourist and physician. After training in medicine and specialising in neurology in the late 19 ...

, who cast him in ''Whistle and I'll Come to You

"Whistle and I'll Come to You" is a 1968 BBC television drama adaptation of the 1904 ghost story 'Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to You, My Lad' by M. R. James. It tells of an eccentric and distracted professor who happens upon a strange whistle whi ...

'', which was recorded for television and received wide praise. Hordern's next major play was ''Jumpers

Jumper or Jumpers may refer to:

Clothing

* Jumper (sweater), a long-sleeve article of clothing; also called a top, pullover, or sweater

**A waist-length top garment of dense wool, part of the Royal Navy uniform and the uniform of the United Stat ...

'' which appeared at the Royal National Theatre

The Royal National Theatre in London, commonly known as the National Theatre (NT), is one of the United Kingdom's three most prominent publicly funded performing arts venues, alongside the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal Opera House. I ...

at the start of 1972. His performance was praised by critics and he reprised the role four years later. His television commitments increased towards the end of his life. His credits include ''Paradise Postponed

''Paradise Postponed'' (1986) is a British 11-episode TV serial based on the 1985 novel by writer John Mortimer. The series covered a span of 30 years of postwar British history, set in a small village.

Plot

The series explores the mystery of ...

'', the BAFTA award-winning ''Memento Mori

''Memento mori'' (Latin for 'remember that you ave todie'BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

adaptation of ''Middlemarch

''Middlemarch, A Study of Provincial Life'' is a novel by the English author Mary Anne Evans, who wrote as George Eliot. It first appeared in eight installments (volumes) in 1871 and 1872. Set in Middlemarch, a fictional English Midland town, ...

''. He was appointed a CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

in 1972 and was knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

eleven years later. Hordern suffered from kidney disease during the 1990s and died from it in 1995 at the age of 83.

Life and career

Early life and education

Hordern was born 3 October 1911 at

Hordern was born 3 October 1911 at Berkhamsted

Berkhamsted ( ) is a historic market town in Hertfordshire, England, in the Bulbourne valley, north-west of London. The town is a civil parish with a town council within the borough of Dacorum which is based in the neighbouring large new town ...

, Hertfordshire, third son of Edward Joseph Calveley Hordern (1867-1945), of a family of Hampshire landed gentry with a strong clerical tradition, and Margaret Emily, daughter of mechanical engineer Edward Francis Murray.

Edward Hordern's father, Rev. Joseph Calveley Hordern, was the rector at the Holy Trinity Church in Bury

Bury may refer to:

*The burial of human remains

*-bury, a suffix in English placenames

Places England

* Bury, Cambridgeshire, a village

* Bury, Greater Manchester, a town, historically in Lancashire

** Bury (UK Parliament constituency) (1832–19 ...

. As a young man Edward joined the Royal Indian Marines and gained the rank of lieutenant. During a short break on home-leave he fell in love with Margaret, after they were introduced by one of his brothers. The courtship was brief and the young couple married in Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

on 28 November 1903. They had their first child, a son, Geoffrey, in 1905, followed by another, Peter, in 1907.

Margaret was descended from James Murray, an Irish physician whose research into digestion led to his discovery of the stomach aid milk of magnesia

Magnesium hydroxide is the inorganic compound with the chemical formula Mg(OH)2. It occurs in nature as the mineral brucite. It is a white solid with low solubility in water (). Magnesium hydroxide is a common component of antacids, such as milk ...

in 1829. The invention earned him a knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

and brought the family great wealth. Margaret grew up in England, and attended St Audries School for Girls in Somerset.

Four years after the birth of Peter, a pregnant Margaret returned to England, where Michael Hordern, her third son, was born. Still stationed abroad, Edward was promoted to the rank of

Four years after the birth of Peter, a pregnant Margaret returned to England, where Michael Hordern, her third son, was born. Still stationed abroad, Edward was promoted to the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

, for which he received a good salary. The family lived in comfort, and Margaret employed a scullery maid

In great houses, scullery maids were the lowest-ranked and often the youngest of the female domestic servants and acted as assistant to a kitchen maid.

Description

The scullery maid reported (through the kitchen maid) to the cook or chef. Along ...

, nanny, groundsman, and full-time cook.Hordern, p. 4.

Margaret left for India to visit her husband in 1916. The trip, although planned only as a short term stay, lasted two years because of the ferocity of the First World War. In her absence, Hordern was sent to Windlesham House School

Windlesham House School is an independent boarding and day school for boys and girls aged 4 to 13 on the South Downs, in Pulborough, West Sussex, England. It was founded in 1837 by Charles Robert Malden and was the first boys' preparatory school ...

in Sussex at the age of five. His young age exempted him from full-time studies but he was allowed to partake in extracurricular activities, including swimming, football, rugby and fishing.Hordern, p. 6. After a few years, and along with a fellow enthusiast, he set up the "A Acting Association" (AAA), a small theatrical committee, which organised productions on behalf of the school. As well as the organisation of plays, Hordern arranged a regular group of players, himself included, to perform various plays which they wrote, directed, and choreographed themselves. He stayed at Windlesham House for nine years, later describing his time there as "enormous fun".

Hordern was 14 when he left Windlesham House to continue his schooling as a member of Chichester House at Brighton College

Brighton College is an independent, co-educational boarding and day school for boys and girls aged 3 to 18 in Brighton, England. The school has three sites: Brighton College (the senior school, ages 11 to 18); Brighton College Preparatory Sc ...

.Sir Michael Hordern''

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'', 4 May 1995, accessed 28 June 2015. By the time of his enrolment, his interest in acting had matured. In his 1993 autobiography, ''A World Elsewhere'', he admitted: "I didn't excel in any area apart from singing; I couldn't read music but I sang quite well." There he helped organise amateur performances of various Gilbert and Sullivan

Gilbert and Sullivan was a Victorian era, Victorian-era theatrical partnership of the dramatist W. S. Gilbert (1836–1911) and the composer Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900), who jointly created fourteen comic operas between 1871 and 1896, of which ...

operas. The first of these was ''The Gondoliers

''The Gondoliers; or, The King of Barataria'' is a Savoy Opera, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert. It premiered at the Savoy Theatre on 7 December 1889 and ran for a very successful 554 performances (at that time the ...

'', in which he played the role of the Duchess. The tutors called his performance a great success, and he was given a position within the men's chorus in the next piece, ''Iolanthe

''Iolanthe; or, The Peer and the Peri'' () is a comic opera with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, first performed in 1882. It is one of the Savoy operas and is the seventh of fourteen operatic collaborations by Gilbert ...

''. Over the next few years, he took part in ''The Mikado

''The Mikado; or, The Town of Titipu'' is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, their ninth of fourteen Gilbert and Sullivan, operatic collaborations. It opened on 14 March 1885, in London, whe ...

'' as a member of the chorus, and then appeared as the Major-General in ''The Pirates of Penzance

''The Pirates of Penzance; or, The Slave of Duty'' is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert, W. S. Gilbert. Its official premiere was at the Fifth Avenue Theatre in New York City on 31 ...

''. It was a period which he later acknowledged as being the start of his career.Hordern, p. 13. When the war ended in 1918, Edward, who was by now a port officer in Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

, arranged for Margaret to return to England. With her, she brought home an orphaned baby girl named Jocelyn, whom she adopted.Hordern, p. 9. The following year, Edward retired from active service and returned to England, where he relocated his family to Haywards Heath

Haywards Heath is a town in West Sussex, England, south of London, north of Brighton, south of Gatwick Airport and northeast of the county town, Chichester. Nearby towns include Burgess Hill to the southwest, Horsham to the northwest, Crawl ...

in Sussex. There, Michael developed a love for fishing, a hobby about which he remained passionate for the rest of his life.

In his autobiography Hordern admitted that his family showed no interest in the theatre and that he had not seen his first professional play, ''Ever Green

Ever may refer to:

* Ever (artist), creator of street art, from Buenos Aires, Argentina

* Ever, Kentucky

* -ever, an English suffix added to interrogative words in forms like ''wherever''

* KT Tech EVER, a South Korean mobile phone manufacturer o ...

'', until he was 19. Around this time he met Christopher Hassall

Christopher Vernon Hassall (24 March 1912 – 25 April 1963) was an English actor, dramatist, librettist, lyricist and poet, who found his greatest fame in a memorable musical partnership with the actor and composer Ivor Novello after work ...

, a fellow student at Brighton College. Hassall, who also went on to have a successful stage career, was, as Hordern noted, instrumental in his decision to become an actor. In 1925 Hordern moved to Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite which forms the uplands dates from the Carboniferous ...

with his family where they converted a disused barn into a farm house. For Hordern the move was ideal; his love of fishing had become stronger and he was able to explore the remote landscape and its isolated rivers.

Early acting career (1930–39)

Theatrical beginnings

Hordern left Brighton College in the early 1930s and secured a job as a teaching assistant in a prep school inBeaconsfield

Beaconsfield ( ) is a market town and civil parish within the unitary authority of Buckinghamshire, England, west-northwest of central London and south-southeast of Aylesbury. Three other towns are within : Gerrards Cross, Amersham and High W ...

. He joined an amateur dramatics

An amateur () is generally considered a person who pursues an avocation independent from their source of income. Amateurs and their pursuits are also described as popular, informal, self-taught, user-generated, DIY, and hobbyist.

History

Hist ...

company and in his spare time, rehearsed for the company's only play, ''Ritzio's Boots'', which was entered into a British Drama League competition, with Hordern in the title role. The play did well but conceded the prize, a professional production at a leading London theatre, to ''Not This Man'', a drama written by Sydney Box

Frank Sydney Box (29 April 1907 – 25 May 1983) was a British film producer and screenwriter, and brother of British film producer Betty Box. In 1940, he founded the documentary film company Verity Films with Jay Lewis.

He produced and co-wro ...

. So envious was he of the rival show's success that Hordern supplied a scathing review to ''The Welwyn Times'' calling Box's show a "blasphemous bunk and cheap theatrical claptrap".Hordern, pp. 30–31. The comment infuriated Box, who issued the actor with a writ to attend court on a count of slander

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

. Hordern won the case and left Box liable for the proceeding's expenses. Years later the two men met on a film set where Box, much to Hordern's surprise, thanked him for helping to kick-start his career in film making, as he had received a lot of publicity as a result of the court case.

With the death of his mother in January 1933, Hordern decided to pursue a professional acting career. He briefly took a job at a prep schoolHordern, p. 40. but fell ill with poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 70% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe sym ...

and had to leave. Upon his recuperation,Hordern, p. 39. he was offered a job as a travelling salesman for the British Educational Suppliers Association

British Educational Suppliers Association (BESA) is a British trade association of manufacturers and distributors of equipment for the education market. Its members supply to both the UK and international markets.

The association has more than 40 ...

, a family-run business belonging to a former school friend at Windlesham House. As part of his job he spent some time in Stevenage

Stevenage ( ) is a large town and borough in Hertfordshire, England, about north of London. Stevenage is east of junctions 7 and 8 of the A1(M), between Letchworth Garden City to the north and Welwyn Garden City to the south. In 1946, Stevena ...

where he joined an amateur dramatics company and appeared in two plays; ''Journey's End

''Journey's End'' is a 1928 dramatic play by English playwright R. C. Sherriff, set in the trenches near Saint-Quentin, Aisne, towards the end of the First World War. The story plays out in the officers' dugout of a British Army infantry comp ...

'', in which he played Raleigh, and ''Diplomacy'', a piece which the actor disliked as he considered it to be "too old-fashioned". Both productions provided him with the chance to work with a cue-script, something which he found to be helpful for the rest of his career. That summer he joined a Shakespearean theatre company which toured stately homes throughout the United Kingdom. His first performance was Orlando

Orlando () is a city in the U.S. state of Florida and is the county seat of Orange County. In Central Florida, it is the center of the Orlando metropolitan area, which had a population of 2,509,831, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures rele ...

in ''As You Like It

''As You Like It'' is a pastoral comedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written in 1599 and first published in the First Folio in 1623. The play's first performance is uncertain, though a performance at Wilton House in 1603 has b ...

'', followed by ''Love's Labour's Lost

''Love's Labour's Lost'' is one of William Shakespeare's early comedies, believed to have been written in the mid-1590s for a performance at the Inns of Court before Elizabeth I of England, Queen Elizabeth I. It follows the King of Navarre and ...

'', in which he co-starred with Osmond Daltry. Hordern admired Daltry's acting ability and later admitted to him being a constant influence on his Shakespearean career.Hordern, p. 41.

In addition to his Shakespearean commitments, Hordern joined the St Pancras People's Theatre, a London-based company partly funded by the theatrical manager Lilian Baylis

Lilian Mary Baylis

CH (9 May 187425 November 1937) was an English theatrical producer and manager. She managed the Old Vic and Sadler's Wells theatres in London and ran an opera company, which became the English National Opera (ENO); a theatre ...

. Hordern enjoyed his time there, despite the tiresome commute between Sussex and London, and stayed with the company for five years. By the end of 1936 he had left his sales job in Beaconsfield to pursue a full-time acting career. He moved into a small flat at Marble Arch

The Marble Arch is a 19th-century white marble-faced triumphal arch in London, England. The structure was designed by John Nash (architect), John Nash in 1827 to be the state entrance to the cour d'honneur of Buckingham Palace; it stood near th ...

and became one of the many jobbing actors eager to make a name for themselves on the London stage.

London debut

Hordern's London debut came in January 1937, as anunderstudy

In theater, an understudy, referred to in opera as cover or covering, is a performer who learns the lines and blocking or choreography of a regular actor, actress, or other performer in a play. Should the regular actor or actress be unable to ap ...

to Bernard Lee

John Bernard Lee (10 January 190816 January 1981) was an English actor, best known for his role as M in the first eleven Eon-produced James Bond films. Lee's film career spanned the years 1934 to 1979, though he had appeared on stage from t ...

in the play ''Night Sky'' at the Savoy Theatre

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre was designed by C. J. Phipps for Richard D'Oyly Carte and opened on 10 October 1881 on a site previously occupied by the Savoy Pala ...

. On nights when he was not required, Hordern would be called upon to undertake the duties of assistant stage manager

Stage management is a broad field that is generally defined as the practice of organization and coordination of an event or theatrical production. Stage management may encompass a variety of activities including the overseeing of the rehearsal p ...

, for which he was paid £2.10s a week. In March, Daltry, who had since formed his own company, Westminster Productions, cast Hordern as Ludovico in ''Othello

''Othello'' (full title: ''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'') is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare, probably in 1603, set in the contemporary Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573) fought for the control of the Island of Cypru ...

''.

The part became Hordern's first paid role as an actor for a theatre company. The play was an instant hit and ran at the People's Theatre in Mile End

Mile End is a district of the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in the East End of London, England, east-northeast of Charing Cross. Situated on the London-to-Colchester road, it was one of the earliest suburbs of London. It became part of the m ...

for two weeks. It also starred the English actor Stephen Murray in the title role, but he became contractually obliged elsewhere towards the end of the run. This allowed Hordern to take his place for which Daltry paid Hordern an extra £1 a week.Hordern, p. 48.

After ''Othellos closure, Daltry undertook a tour of Scandinavia and the Baltic with two plays, ''Outward Bound

Outward Bound (OB) is an international network of outdoor education organizations that was founded in the United Kingdom by Lawrence Holt and Kurt Hahn in 1941. Today there are organizations, called schools, in over 35 countries which are att ...

'', and ''Arms and the Man

''Arms and the Man'' is a comedy by George Bernard Shaw, whose title comes from the opening words of Virgil's ''Aeneid'', in Latin:

''Arma virumque cano'' ("Of arms and the man I sing").

The play was first produced on 21 April 1894 at the Aven ...

''. He employed Hordern in both with the first being the more successful. It was a time that the actor recognised as being a turning point in his professional acting career. On his return to London, and after spending a few weeks in unemployment, he was offered a part in the ill-fated ''Ninety Sail''. The play, about Sir Christopher Wren's time in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

, was cancelled on the day Hordern was due to start work, with "unforeseen problems" cited as the reason by its producers.

Bristol repertory theatre

In mid-1937 the theatre proprietor Ronald Russell offered Hordern a part in his

In mid-1937 the theatre proprietor Ronald Russell offered Hordern a part in his repertory

A repertory theatre is a theatre in which a resident company presents works from a specified repertoire, usually in alternation or rotation.

United Kingdom

Annie Horniman founded the first modern repertory theatre in Manchester after withdrawing ...

company, the Rapier Players, who were then based at Colston Hall

Bristol Beacon, previously known as Colston Hall, is a concert hall and Grade II listed building on Colston Street, Bristol, England. It is owned by Bristol City Council. Since 2011, management of the hall has been the direct responsibility of ...

in Bristol. Hordern's first acting role within the company was as Uncle HarryHordern, pp. 52–53. in the play '' Someone at the Door''. Because of the play's success, Russell employed him in the same type of role, the monotony of which frustrated the actor who longed to play the leading man

A leading actor, leading actress, or simply lead (), plays the role of the protagonist of a film, television show or play. The word ''lead'' may also refer to the largest role in the piece, and ''leading actor'' may refer to a person who typica ...

. It was whilst with the Rapier Players that Hordern fell in love with Eve Mortimer, a juvenile actress who appeared in minor roles in many of Russell's productions. Hordern considered his experience with the Rapier Players to be invaluable; it taught him how a professional theatre company worked under a strict time frame and how it operated with an even stricter budget. He was allowed two minutes to study each page of the script, but because of the frequent mistakes and many stalled lines, rehearsals became long and laborious. Hordern described the company's props

A prop, formally known as (theatrical) property, is an object used on stage or screen by actors during a performance or screen production. In practical terms, a prop is considered to be anything movable or portable on a stage or a set, distinc ...

as being made to a very high standard, despite being bought on a shoe-string budget.

After a brief holiday with Eve in Scotland in 1938,Hordern, p. 57. Hordern returned to London, where he appeared in ''Quinneys'', a radio play broadcast by the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

in June of that year. The main part went to Henry Ainley

Henry Hinchliffe Ainley (21 August 1879 – 31 October 1945) was an English actor.

Life and career

Early years

Ainley was born in Morley, near Leeds, on 21 August 1879, the only son and eldest child of Richard Ainley (1851–1919), a textile ...

whom Hordern described as "a great actor, who, sadly, was past his best".

Hordern then made a return to Bristol to prepare for the following season with the Rapier Players. One production singled out in the ''Western Daily Press

The ''Western Daily Press'' is a regional newspaper covering parts of South West England, mainly Gloucestershire, Wiltshire and Somerset as well as the metropolitan areas of Bath and North East Somerset and the Bristol area. It is published Mon ...

'' as particularly good was ''Love in Idleness'', in which Hordern played the lead character. A reporter for the paper thought that the play "had been noticed" among theatrical critics and that the players "filled their respective roles excellently".

By the end of 1938 Hordern's father had sold the family home and had bought a cottage in Holt

Holt or holte may refer to:

Natural world

*Holt (den), an otter den

* Holt, an area of woodland

Places Australia

* Holt, Australian Capital Territory

* Division of Holt, an electoral district in the Australian House of Representatives in Vic ...

, near Bath, Somerset

Bath () is a city in the Bath and North East Somerset unitary area in the county of Somerset, England, known for and named after its Roman-built baths. At the 2021 Census, the population was 101,557. Bath is in the valley of the River Avon, ...

. The arrangement was convenient for the young actor, who used the premises as a base while he appeared in shows with the Rapier Players. One such piece was an adaption of Stella Gibbons

Stella Dorothea Gibbons (5 January 1902 – 19 December 1989) was an English writer, journalist, and poet. She established her reputation with her first novel, ''Cold Comfort Farm'' (1932) which has been reprinted many times. Although she ...

's ''Cold Comfort Farm

''Cold Comfort Farm'' is a comic novel by English author Stella Gibbons, published in 1932. It parodies the romanticised, sometimes doom-laden accounts of rural life popular at the time, by writers such as Mary Webb.

Plot summary

Following ...

'', which starred Mabel Constanduros

Mabel Constanduros (' Tilling; 29 March 1880 – 8 February 1957) was an English actress and screenwriter. She gained public notice playing Mrs.Buggins on the radio programme '' The Buggins Family'', which ran from 1928 to 1948. As well as writi ...

, who had adapted the book with Gibbons's permission. Hordern was cast in the supporting role of Seth, a part he described as being fun to perform. The modernised script was "adored" by the cast, according to Hordern, but loathed by the audience who expected it to be exactly like the book.

Second World War and film debut

Hordern and Eve left Bristol in 1939 forHarrogate

Harrogate ( ) is a spa town and the administrative centre of the Borough of Harrogate in North Yorkshire, England. Historic counties of England, Historically in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the town is a tourist destination and its visitor at ...

, where Eve joined a small repertory company called the White Rose Players. After a brief spell of unemployment, and with the outbreak of war, Hordern volunteered for a post within the Air Raid Precautions

Air Raid Precautions (ARP) refers to a number of organisations and guidelines in the United Kingdom dedicated to the protection of civilians from the danger of air raids. Government consideration for air raid precautions increased in the 1920s an ...

(ARP).Hordern, pp. 57–59. He was accepted but soon grew frustrated at not being able to conduct any rescues because of the lack of enemy action. He decided that it was "not a very good way to fight the war" and enlisted instead as a gunner with the Royal Navy. While he was waiting to be accepted he and Eve responded to an advertisement in ''The Stage

''The Stage'' is a British weekly newspaper and website covering the entertainment industry and particularly theatre. It was founded in 1880. It contains news, reviews, opinion, features, and recruitment advertising, mainly directed at those wh ...

'' for actors in a repertory company in Bath. They were appointed as the company's leading man and lady. Their first and only engagement was in a play entitled ''Bats in the Belfry'' which opened at the city's Assembly Rooms

In Great Britain and Ireland, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, assembly rooms were gathering places for members of the higher social classes open to members of both sexes. At that time most entertaining was done at home and there were ...

on 16 October. Hordern's elation at finally becoming a leading man was short-lived when he received his call-up that December. In the interest of helping to boost public morale, Hordern sought permission from the navy to allow him to complete his theatrical commitment in Bath and to appear in his first film, a thriller called ''Girl in the News

''The Girl in the News'' is a 1940 British thriller film directed by Carol Reed and starring Margaret Lockwood, Barry K. Barnes and Emlyn Williams. It was based on the eponymous novel by Roy Vickers, released the same year.

Plot

After her el ...

'', directed by Carol Reed

Sir Carol Reed (30 December 1906 – 25 April 1976) was an English film director and producer, best known for ''Odd Man Out'' (1947), '' The Fallen Idol'' (1948), ''The Third Man'' (1949), and '' Oliver!'' (1968), for which he was awarded the ...

; his request was accepted, and he was told to report for duty at Plymouth Barracks in the early months of 1940 when the show had finished and he was free from filming responsibilities.

In 1940, after a minor role in ''Without the Prince'' at the Whitehall Theatre, Hordern played the small, uncredited part of a BBC official alongside James Hayter in Arthur Askey's comedy film ''

In 1940, after a minor role in ''Without the Prince'' at the Whitehall Theatre, Hordern played the small, uncredited part of a BBC official alongside James Hayter in Arthur Askey's comedy film ''Band Waggon

''Band Waggon'' was a comedy radio show broadcast by the BBC from 1938 to 1940. The first series featured Arthur Askey and Richard Murdoch, Richard "Stinker" Murdoch. In the second series, Askey and Murdoch were joined by Syd Walker, and the thir ...

''. Soon after, he began his naval gunnery training on board ''City of Florence'', a defensively equipped merchant ship

Defensively equipped merchant ship (DEMS) was an Admiralty Trade Division programme established in June 1939, to arm 5,500 British merchant ships with an adequate defence against enemy submarines and aircraft. The acronym DEMS was used to descri ...

(DEMS) which delivered ammunition to the city of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

for the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

. He found that although his middle class upbringing hindered his ability to make friends on board the ship, it helped with his commanding officers.Hordern, pp. 66–67.

By 1941 radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

was slowly being introduced to the Navy and Hordern was appointed as one of the first operatives who communicated enemy movements to the RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

. He later said the post was owed to his clear diction and deep vocal range. His commentary impressed his superior officers so much that by early 1942 he had been given the job as a Fighter Direction Officer and then first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

on board . Shortly after the departure of his superior, he was promoted to lieutenant commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding rank i ...

, a rank which he held for two years. Alongside his naval responsibilities, he was also appointed as the ship's entertainment officer and was responsible for organising shows featuring members of the crew.

Marriage and post-war years

During a short visit to Liverpool in 1943, Hordern proposed to Eve; they married on 27 April of that year with the actorCyril Luckham

Cyril Alexander Garland Luckham (25 July 1907 – 8 February 1989) was an English film, television and theatre actor. He was the husband of stage and screen actress Violet Lamb.

Career

The son of a paymaster captain in the Royal Navy, Cyril Lu ...

as best man. After the honeymoon, Hordern resumed his duties on ''Illustrious'' while Eve returned to repertory theatre in Southport

Southport is a seaside town in the Metropolitan Borough of Sefton in Merseyside, England. At the 2001 census, it had a population of 90,336, making it the eleventh most populous settlement in North West England.

Southport lies on the Irish ...

. In the months after the end of the war in 1945, he was transferred to the Admiralty where he worked briefly as a ship dispatcher. The Horderns rented a flat in Elvaston Place

Elvaston Place is a street in South Kensington, London.

Elvaston Place runs west to east from Gloucester Road to Queen's Gate.

The Embassy of Gabon, London is at number 27. The High Commission of Mauritius, London is at number 32/33. The Embas ...

in Kensington

Kensington is a district in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in the West End of London, West of Central London.

The district's commercial heart is Kensington High Street, running on an east–west axis. The north-east is taken up b ...

, London, and he began to seek work as an actor. After a short while, he was approached by André Obey

André Obey (; 8 May 1892 at Douai, France – 11 April 1975 at Montsoreau, near the river Loire) was a prominent French playwright during the inter-war years, and into the 1950s.

He began as a novelist and produced an autobiographical novel abou ...

who cast him in his first television role, Noah, in a play adapted from the book of the same name. Hordern was apprehensive about performing in the new medium and found the rehearsal and live performance to be exhausting; but he was generously paid, earning £45 for the entire engagement.Hordern, p. 80.

Hordern's first role in 1946 came as Torvald Helmar in ''A Doll's House

''A Doll's House'' (Danish and nb, Et dukkehjem; also translated as ''A Doll House'') is a three-act play written by Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen. It premiered at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, Denmark, on 21 December 1879, having bee ...

'' at the Intimate Theatre

The Intimate Theatre was a repertory theatre in Palmers Green, London from 1937 to 1987, and is the name commonly used for St. Monica's Church Hall.

History

St. Monica's Church Hall was built in 1931, and the actor John Clements turned the buil ...

in Palmers Green

Palmers Green is a suburban area and electoral ward in North London, England, within the London Borough of Enfield. It is located within the N13 postcode district, around north of Charing Cross. It is home to the largest population of Greek Cy ...

.Hordern, p. 82. This was followed by the part of Richard Fenton, a murder victim, in ''Dear Murderer'' which premiered at the Aldwych Theatre

The Aldwych Theatre is a West End theatre, located in Aldwych in the City of Westminster, central London. It was listed Grade II on 20 July 1971. Its seating capacity is 1,200 on three levels.

History

Origins

The theatre was constructed in th ...

on 31 July. The play was a success and ran for 85 performances until its closure on 12 October. ''Dear Murderer'' thrilled the critics and Hordern was singled out by one reporter for the ''Hull Daily Mail

The ''Hull Daily Mail'' is an English regional daily newspaper for Kingston upon Hull, in the East Riding of Yorkshire. The ''Hull Daily Mail'' has been circulated in various guises since 1885. A second edition, the ''East Riding Mail'', covers ...

'' who thought that the actor brought "sincerity to a difficult role". The following month Eve gave birth to the couple's only child, a daughter, Joanna, who was born at Queen Charlotte's Hospital

Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea Hospital is one of the oldest maternity hospitals in Europe, founded in 1739 in London. Until October 2000, it occupied a site at 339–351 Goldhawk Road, Hammersmith, but is now located between East Acton and White ...

in Chelsea

Chelsea or Chelsey may refer to:

Places Australia

* Chelsea, Victoria

Canada

* Chelsea, Nova Scotia

* Chelsea, Quebec

United Kingdom

* Chelsea, London, an area of London, bounded to the south by the River Thames

** Chelsea (UK Parliament consti ...

. That Christmas he took the role of Nick Bottom

Nick Bottom is a character in Shakespeare's ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' who provides comic relief throughout the play. A weaver by trade, he is famously known for getting his head transformed into that of a donkey by the elusive Puck. Bott ...

in a festive reworking of Henry Purcell

Henry Purcell (, rare: September 1659 – 21 November 1695) was an English composer.

Purcell's style of Baroque music was uniquely English, although it incorporated Italian and French elements. Generally considered among the greatest E ...

's ''The Fairy-Queen

''The Fairy-Queen'' (1692; Purcell catalogue number Z.629) is a semi-opera by Henry Purcell; a "Restoration spectacular". The libretto is an anonymous adaptation of William Shakespeare's comedy '' A Midsummer Night's Dream''. First performed ...

''. The play was the first performance by the Covent Garden Opera Company, which later became known as The Royal Opera

The Royal Opera is a British opera company based in central London, resident at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden. Along with the English National Opera, it is one of the two principal opera companies in London. Founded in 1946 as the Cove ...

.

Towards the end of April 1947, Hordern accepted the small part of Captain Hoyle in Richard Llewellyn's comic drama film ''Noose''. Two other roles occurred that year: as Maxim de Winter in a television adaption of Daphne du Maurier's novel ''Rebecca

Rebecca, ; Syriac: , ) from the Hebrew (lit., 'connection'), from Semitic root , 'to tie, couple or join', 'to secure', or 'to snare') () appears in the Hebrew Bible as the wife of Isaac and the mother of Jacob and Esau. According to biblical ...

'', followed by the part of a detective in ''Good-Time Girl

''Good-Time Girl'' is a 1948 British film noir-crime drama film directed by David MacDonald. A homeless girl is asked to explain her bad behaviour in the juvenile court, and says she’s run away from home because she’s unhappy there. They ex ...

'', alongside Dennis Price

Dennistoun Franklyn John Rose Price (23 June 1915 – 6 October 1973) was an English actor, best remembered for his role as Louis Mazzini in the film ''Kind Hearts and Coronets'' (1949) and for his portrayal of the omnicompetent valet Jeeves ...

and Jean Kent

Jean Kent (born Joan Mildred Field; 29 June 1921 − 30 November 2013) was an English film and television actress.

Biography

Born Joan Mildred Field (sometimes incorrectly cited as Summerfield) in Brixton, London in 1921, the only child of va ...

. The following year he took part in three plays: Peter Ustinov's ''The Indifferent Shepherd'', which appeared at the newly opened Q Theatre

The Q Theatre was a British theatre located near Kew Bridge in Brentford, west London, which operated between 1924 and 1958. It was built on the site of the former Kew Bridge Studios.

The theatre, seating 490 in 25 rows with a central aisle, wa ...

in Brentford

Brentford is a suburban town in West London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It lies at the confluence of the River Brent and the Thames, west of Charing Cross.

Its economy has diverse company headquarters buildings whi ...

, West London; Ibsen's ''Ghosts

A ghost is the soul or spirit of a dead person or animal that is believed to be able to appear to the living. In ghostlore, descriptions of ghosts vary widely from an invisible presence to translucent or barely visible wispy shapes, to rea ...

''; and an adaptation of ''The Wind in the Willows

''The Wind in the Willows'' is a children's novel by the British novelist Kenneth Grahame, first published in 1908. It details the story of Mole, Ratty, and Badger as they try to help Mr. Toad, after he becomes obsessed with motorcars and gets ...

'' at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre

The Royal Shakespeare Theatre (RST) (originally called the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre) is a grade II* listed 1,040+ seat thrust stage theatre owned by the Royal Shakespeare Company dedicated to the English playwright and poet William Shakespea ...

in Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon (), commonly known as just Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-we ...

in which he portrayed the part of the blustery, eccentric Mr Toad.Hordern, p. 86.

In early 1949 Hordern appeared as Pascal in the Michael Redgrave

Sir Michael Scudamore Redgrave CBE (20 March 1908 – 21 March 1985) was an English stage and film actor, director, manager and author. He received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in ''Mourning Becomes Elect ...

-directed comedy ''A Woman in Love'', but disliked the experience because of the hostile relationship between Redgrave and the show's star, Margaret Rawlings

Margaret Rawlings, Lady Barlow (5 June 1906 – 19 May 1996) was an English stage actress, born in Osaka, Japan, daughter of the Rev. George William Rawlings and his wife Lilian (née Boddington) Rawlings. Personal life/affiliations

She was e ...

.Hordern, p. 88. Next, he was engaged in the minor role of Bashford in the critically acclaimed Ealing comedy

The Ealing comedies is an informal name for a series of comedy films produced by the London-based Ealing Studios during a ten-year period from 1947 to 1957. Often considered to reflect Britain's post-war spirit, the most celebrated films in the ...

''Passport to Pimlico

''Passport to Pimlico'' is a 1949 British comedy film made by Ealing Studios and starring Stanley Holloway, Margaret Rutherford and Hermione Baddeley. It was directed by Henry Cornelius and written by T. E. B. Clarke. The story concerns the unea ...

'', a performance which he described as "tense and hyperactive".

1950–1960s

''Ivanov'' and ''Saint's Day''

By the 1950s Hordern had come to the notice of many influential directors. In his autobiography, the actor recognised the decade as being an important era of his career. It started with a major role in Anton Chekhov's ''Ivanov

Ivanov, Ivanoff or Ivanow (masculine, bg, Иванов, russian: ИвановSometimes the stress is on Ива́нов in Bulgarian if it is a middle name, or in Russian as a rare variant of pronunciation), or Ivanova (feminine, bg, Иванов ...

'' in 1950. The production took place at the Arts Theatre

The Arts Theatre is a theatre in Great Newport Street, in Westminster, Central London.

History

It opened on 20 April 1927 as a members-only club for the performance of unlicensed plays, thus avoiding theatre censorship by the Lord Chamberl ...

in Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

and excited audiences because of its 25-year absence from the English stage. The writer T. C. Worsley

Thomas Cuthbert Worsley (1907–1977) was a British teacher, writer, editor, and theatre and television critic. He is best remembered for his autobiographical '' Flannelled Fool: A Slice of a Life in the Thirties''.

Biography

Cuthbert Worsley wa ...

was impressed by Hordern's performance and wrote: "Perhaps an actor with star quality might have imposed on us more successfully than Mr Michael Hordern, and won our sympathy for Ivanov by his own personality. But such a performance would have raised the level of expectation all round. As it is, Mr Hordern is rich in intelligence, sensitivity and grasp, and with very few exceptions, the company give his impressive playing the right kind of support." The title character in ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'', directed by Alec Clunes

Alexander Sheriff de Moro Clunes (17 May 1912 – 13 March 1970) was an English actor and theatrical manager.

Among the plays he presented were Christopher Fry's ''The Lady's Not For Burning''. He gave the actor and dramatist Peter Ustinov h ...

, was Hordern's next engagement. Critics wrote of their dislike of Clunes's version, but the theatre reviewer Audrey Williamson

Audrey Doreen Swayne Williamson (''later Mitchell'') (28 September 1926 – 29 April 2010)John Whiting

John Robert Whiting (15 November 1917 – 16 June 1963) was an English actor, dramatist and critic.

Life and career

Born in Salisbury, he was educated at Taunton School, "the particular hellish life which is the English public school" as he ...

, trying to make a name for himself in the theatre after the war, was called by Clunes to take part in a theatrical competition at the Arts Theatre

The Arts Theatre is a theatre in Great Newport Street, in Westminster, Central London.

History

It opened on 20 April 1927 as a members-only club for the performance of unlicensed plays, thus avoiding theatre censorship by the Lord Chamberl ...

in London in 1951, for which he entered his play ''Saint's Day''. Several other amateur directors also competed for the prize, which was to have their play funded and professionally displayed at the Arts. Having seen him perform the previous year, Whiting hired Hordern for the lead role of Paul Southman, a cantankerous old poet who fights off three rebellious army deserters who threaten the tranquillity of his sleepy country village."Saint's Day"by Michael Billington. ''The Guardian'', 25 October 2002, accessed 21 August 2015. The play proved popular with audiences, but not so with theatrical commentators. Hordern liked the piece, calling it "bitter and interesting",Hordern, p. 90. but the press, who extensively reported on the competition throughout each stage, thought differently and condemned it for winning. This infuriated the actors

Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

and John Gielgud

Sir Arthur John Gielgud, (; 14 April 1904 – 21 May 2000) was an English actor and theatre director whose career spanned eight decades. With Ralph Richardson and Laurence Olivier, he was one of the trinity of actors who dominated the Briti ...

, who wrote letters of complaint to the press.

Shakespeare Memorial Theatre

Hordern cited ''Saint's Day''s negative publicity as having done his career "the power of good" as it brought him to the attention of the director

Hordern cited ''Saint's Day''s negative publicity as having done his career "the power of good" as it brought him to the attention of the director Glen Byam Shaw

Glencairn Alexander "Glen" Byam Shaw, CBE (13 December 1904 – 29 April 1986) was an English actor and theatre director, known for his dramatic productions in the 1950s and his operatic productions in the 1960s and later.

In the 1920s and 1930s ...

, who cast him in a series of plays at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in 1951. Among the roles were Caliban

Caliban ( ), son of the witch Sycorax, is an important character in William Shakespeare's play '' The Tempest''.

His character is one of the few Shakespearean figures to take on a life of its own "outside" Shakespeare's own work: as Russell ...

in '' The Tempest'', Jaques Jaques is a given name and surname, a variant of Jacques.

People with the given name Jaques

* Jaques Bagratuni (1879-1943), Armenian prince

* Jaques Bisan (b. 1993) Beninese footballer

* Jaques Étienne Gay (1786-1864) Swiss-French botanist

* Jaq ...

in ''As You Like It'', and Sir Politick Would-Be in Ben Jonson's comedy ''Volpone

''Volpone'' (, Italian for "sly fox") is a comedy play by English playwright Ben Jonson first produced in 1605–1606, drawing on elements of city comedy and beast fable. A merciless satire of greed and lust, it remains Jonson's most-perform ...

''. Hordern claimed to know very little about the bard's works and sought advice from friends about how best to prepare for the roles. The same year, he travelled down to Nettlefold Studios

Walton Studios, previously named Hepworth Studios and Nettlefold Studios, was a film production studio in Walton-on-Thames in Surrey, England.Walton-on-Thames

Walton-on-Thames, locally known as Walton, is a market town on the south bank of the Thames in the Elmbridge borough of Surrey, England. Walton forms part of the Greater London built-up area, within the KT postcode and is served by a wide ran ...

, to film '' Scrooge'', an adaptation of Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

's ''A Christmas Carol

''A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas'', commonly known as ''A Christmas Carol'', is a novella by Charles Dickens, first published in London by Chapman & Hall in 1843 and illustrated by John Leech. ''A Christmas C ...

'', in which he played Marley's ghost

Jacob Marley is a fictional character in Charles Dickens's 1843 novella ''A Christmas Carol'', a former business partner of the miser Ebenezer Scrooge, who has been dead for seven years.Hawes, Donal''Who's Who in Dickens'' Routledge (1998), Goog ...

. Reviews were mixed with ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' giving it a favourable write-up, while ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine remained ambivalent. The ''Aberdeen Evening Express'' echoed the comments made by an American reviewer by calling ''Scrooge'' a "trenchant and inspiring Christmas show". The author Fred Guida, writing in his book ''Christmas Carol and Its Adaptations: A Critical Examination'' in 2000, thought that Marley's ghost, though a "small but pivotal role", was "brilliantly played" by Hordern.

With the first play of the season imminent, the Horderns moved to Stratford and took temporary accommodation at Goldicote House, a large country property situated on the River Avon. The first of his two plays, ''The Tempest'', caused Hordern to doubt his own acting ability when he compared his interpretation of Caliban to that of Alec Guinness

Sir Alec Guinness (born Alec Guinness de Cuffe; 2 April 1914 – 5 August 2000) was an English actor. After an early career on the stage, Guinness was featured in several of the Ealing comedies, including ''Kind Hearts and Coronets'' (194 ...

, who had played the same role four years earlier. Reassured by Byam Shaw, Hordern remained in the role for the entire run. A few days later, the actor was thrilled to receive a letter of appreciation from Michael Redgrave, who thought Hordern's Caliban was "immensely fine, with all the pity and pathos... but with real terror and humour as well".Hordern, p. 93. More praise was received as the season continued; an anonymous theatre reviewer, quoted in Hordern's autobiography, called the actor's portrayal of Menenius Aggripa "a dryly acute study of the 'humorous patrician' and one moreover that can move our compassion in the Volscian cameo", before going on to say "we had felt that it would be long before Alec Guinness's Menenius could be matched. The fact that Michael Hordern's different reading can now stand beside the other does credit to a player who will be a Stratford prize."Hordern, p. 94.

The Old Vic

Hordern's contract at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre lasted until mid-1952, and on its expiration, he secured a position within Michael Benthall's theatrical company at

Hordern's contract at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre lasted until mid-1952, and on its expiration, he secured a position within Michael Benthall's theatrical company at the Old Vic

The Old Vic is a 1,000-seat, nonprofit organization, not-for-profit producing house, producing theatre in Waterloo, London, Waterloo, London, England. Established in 1818 as the Royal Coburg Theatre, and renamed in 1833 the Royal Victoria Th ...

in London. The company's first play, ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'', starred Richard Burton

Richard Burton (; born Richard Walter Jenkins Jr.; 10 November 1925 – 5 August 1984) was a Welsh actor. Noted for his baritone voice, Burton established himself as a formidable Shakespearean actor in the 1950s, and he gave a memorable pe ...

, Claire Bloom

Patricia Claire Bloom (born 15 February 1931) is an English actress. She is known for leading roles in plays such as ''A Streetcar Named Desire,'' ''A Doll's House'', and '' Long Day's Journey into Night'', and has starred in nearly sixty film ...

, and Fay Compton

Virginia Lilian Emmeline Compton-Mackenzie, (; 18 September 1894 – 12 December 1978), known professionally as Fay Compton, was an English actress. She appeared in several films, and made many broadcasts, but was best known for her stage per ...

,Hordern, p. 96. and opened on 14 September 1953. Hordern called it "the perfect play with which to open the season" as it featured "fine strong parts for everyone and asa good showpiece for an actor's latent vanity".Hordern, p. 97. Shortly after opening, it was transferred to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, where it took part at the Fringe

Fringe may refer to:

Arts

* Edinburgh Festival Fringe, the world's largest arts festival, known as "the Fringe"

* Adelaide Fringe, the world's second-largest annual arts festival

* Fringe theatre, a name for alternative theatre

* The Fringe, the ...

before returning to London. For his role of Polonius

Polonius is a character in William Shakespeare's play ''Hamlet''. He is chief counsellor of the play's ultimate villain, Claudius, and the father of Laertes and Ophelia. Generally regarded as wrong in every judgment he makes over the course of ...

, Hordern received mixed reviews, with one critic saying: "He was at his best in his early scenes with Ophelia... but towards the end of the performance he began to obscure less matter with more art". After Edinburgh, Benthall took ''Hamlet'' on a provincial tour and the play had a successful run of 101 performances.

In mid-1953 the Danish government invited Benthall and his company to Helsingør (Elsinore) to perform ''Hamlet'' for the Norwegian Royal Family. The play was well received by the royals. On the whole, the actor enjoyed his time in ''Hamlet'' but behind the scenes, relations between him and Burton were strained. Hordern noted his colleague's "likeability, charm and charisma"Quote by the author; Hordern, p. 98. but thought that Burton had a tendency to get easily "ratty"Quote by the author; Hordern, p. 99. with him in social situations. Hordern described their working relationship as "love-hate" and admitted they were envious of each other's success; Burton of Hordern because of the latter's good reviews, and Hordern of Burton who received more attention from fans. When Burton left for Hollywood years later, he recommended Hordern to various casting directors; Hordern was subsequently engaged in six of Burton's films.

''King John King John may refer to:

Rulers

* John, King of England (1166–1216)

* John I of Jerusalem (c. 1170–1237)

* John Balliol, King of Scotland (c. 1249–1314)

* John I of France (15–20 November 1316)

* John II of France (1319–1364)

* John I o ...

'' was next for Benthall's company and opened on 26 October 1953."The Old Vic Company: The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark"the Old Vic theatre programme: 1953/54 season, accessed 25 August 2015. The lead character initially went to an unknown and inexperienced young actor, but the part was re-cast with Hordern in the role.Hordern, p. 100. Hordern described ''King John'' as being "a difficult play in the sense that it has no common purpose or apparent theme". Simultaneously to this, he was commuting back to

Pinewood Studios

Pinewood Studios is a British film and television studio located in the village of Iver Heath, England. It is approximately west of central London.

The studio has been the base for many productions over the years from large-scale films to te ...

where he was filming ''Forbidden Cargo Forbidden Cargo may refer to:

* Forbidden Cargo (1925 film), ''Forbidden Cargo'' (1925 film), an American film starring Boris Karloff: rum-running from Bahamas to United States

* Forbidden Cargo (1954 film), ''Forbidden Cargo'' (1954 film), a Brit ...

''. The hectic schedule brought on a bout of exhaustion for which he received medical advice to reduce his workload.