Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller ( ; born Meta Vaux Warrick; June 9, 1877 – March 18, 1968) was an

Due to her parents' success, she was given access to various cultural and educational opportunities. Warrick trained in art, music, dance and

Due to her parents' success, she was given access to various cultural and educational opportunities. Warrick trained in art, music, dance and

African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

artist who celebrated Afrocentric themes. At the fore of the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

, Warrick was known for being a poet, painter, theater designer, and sculptor of the black American experience. At the turn of the 20th century, she had achieved a reputation as the first black sculptress and was a well-known sculptor in Paris before returning to the United States. Warrick was a protégée of Auguste Rodin

François Auguste René Rodin (12 November 184017 November 1917) was a French sculptor, generally considered the founder of modern sculpture. He was schooled traditionally and took a craftsman-like approach to his work. Rodin possessed a uniqu ...

, and has been described as "one of the most imaginative Black artists of her generation." The editors compare Warrick with her contemporary, May Howard Jackson, another African-American sculptor from Philadelphia, who was also born in 1877. Through adopting a horror-based figural style and choosing to depict events of racial injustice, like the lynching of Mary Turner, Warrick used her platform to address the societal traumas of African Americans.

Early life

Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller was born inPhiladelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, on June 9, 1877. Her parents were Emma (née Jones) Warrick, an accomplished wig maker and beautician

Cosmetology (from Greek , ''kosmētikos'', "beautifying"; and , ''-logia'') is the study and application of beauty treatment. Branches of specialty include hairstyling, skin care, cosmetics, manicures/pedicures, non-permanent hair removal such as ...

for upperclass white women, and William H. Warrick, a successful barber

A barber is a person whose occupation is mainly to cut, dress, groom, style and shave men's and boys' hair or beards. A barber's place of work is known as a "barbershop" or a "barber's". Barbershops are also places of social interaction and publi ...

and caterer. Her father owned several barber shops and her mother owned her own beauty salon. Warrick was, in fact, named after Meta Vaux, the daughter of Senator Richard Vaux

Richard Vaux (December 19, 1816 – March 22, 1895) was an American politician. He was mayor of Philadelphia and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania.

Early life and education

Richard Vaux was born in Philadelphia, P ...

, one of her mother's customers. Her maternal grandfather, Henry Jones, was a successful caterer in the city. Both of her parents were considered to have influential positions in African-American society.

Her family's class status was a special privilege that was afforded to them through their talent and their location. After an influx of free blacks began making a home in Philadelphia, the available jobs were generally physically hard and low-paying. Only a few people were able to find desirable jobs as ministers, physicians, barbers, teachers, and caterers. During the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

, due to racism, legalized racial segregation laws, including Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

limited social progress of African Americans into the 20th century. Despite this, Warrick's parents were able to find creative success amongst the "vibrant political, cultural, and economic center" the African-American community of Philadelphia had established.

Due to her parents' success, she was given access to various cultural and educational opportunities. Warrick trained in art, music, dance and

Due to her parents' success, she was given access to various cultural and educational opportunities. Warrick trained in art, music, dance and horseback riding

Equestrianism (from Latin , , , 'horseman', 'horse'), commonly known as horse riding (Commonwealth English) or horseback riding (American English), includes the disciplines of riding, driving, and vaulting. This broad description includes the ...

. Warrick's art education and art influences began at home, nurtured from childhood by her older sister Blanche, who studied art, and visits to Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) is a museum and private art school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her older sister, who later became a beautician like their mother, kept clay that Meta was able to use to create art. She was enrolled in 1893 in the Girls' High School in Philadelphia, where she studied art as well as academic courses. Warrick was among the few gifted artists selected from the Philadelphia public schools to study art and design at J. Liberty Tadd's art program at the Philadelphia School of Industrial Art in the early 1890s.

Her brother and grandfather entertained and fascinated her with endless horror stories. These influences partly shaped her sculpture, as she eventually developed as an internationally trained artist known as "the sculptor of horrors."

Marriage and family

In 1907, Warrick marriedDr. Solomon Carter Fuller

Solomon Carter Fuller (August 1, 1872 – January 16, 1953) was a pioneering Liberian neurologist, psychiatrist, pathologist, and professor. Born in Monrovia, Liberia, he completed his college education and medical degree (MD) in the United States ...

, a prominent physician and psychiatrist, known for his work with Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegeneration, neurodegenerative disease that usually starts slowly and progressively worsens. It is the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in short-term me ...

. Born in Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

, Dr. Fuller was one of the first black psychiatrists in the United States. The couple settled on Warren Road in Framingham, Massachusetts

Framingham () is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. Incorporated in 1700, it is located in Middlesex County and the MetroWest subregion of the Greater Boston metropolitan area. The city proper covers with a popu ...

where they were one of the first black families to join the community. She continued to create works of art, against the stigma that she should settle down and become a housewife once she and her husband had three children one of which , her son Perry, went on to become a sculptor as well. Prominent African-American people visited their house, as did the Prince of Siam. Within the community, Warrick Fuller helped establish and was involved in the lighting of productions put on by the Framingham Dramatic Society. She was an active member of the St. Andrew's Episcopal Church where she directed and costumed their plays and pageants.

After the fire in 1910, Warrick Fuller built a studio in the back of her house, something which her husband strongly opposed. Between domestic duties, she found herself inspired by her religion and began to sculpt traditional biblical scenes. Warrick believed making art was her divine calling so her being cast out didn't discourage her reignited motivation to create.

Dr. Fuller died in 1953. Warrick Fuller died on March 18, 1968, at Cardinal Cushing Hospital in Framingham, Massachusetts

Framingham () is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. Incorporated in 1700, it is located in Middlesex County and the MetroWest subregion of the Greater Boston metropolitan area. The city proper covers with a popu ...

.

Education

Warrick's career as an artist began after one of her high-school projects was chosen to be included in the 1893World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordi ...

in Chicago. Based upon this work, she won a four-year scholarship to the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art The Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art (PMSIA), also referred to as the School of Applied Art, was chartered by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania on February 26, 1876, as both a museum and teaching institution. This was in response to t ...

(now The University of the Arts

The University of the Arts (UArts) is a private art university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Its campus makes up part of the Avenue of the Arts in Center City, Philadelphia. Dating back to the 1870s, it is one of the oldest schools of art o ...

College of Art and Design) in 1894, where her gift for sculpture emerged. In an act of independence and nonconformity as an up-and-coming woman artist, Warrick defied traditionally "feminine" themes by sculpting pieces influenced by the gruesome imagery found in the ''fin de siècle

() is a French term meaning "end of century,” a phrase which typically encompasses both the meaning of the similar English idiom "turn of the century" and also makes reference to the closing of one era and onset of another. Without context ...

'' movement of the Symbolist

Symbolism was a late 19th-century art movement of French and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts seeking to represent absolute truths symbolically through language and metaphorical images, mainly as a reaction against naturalism and realis ...

era. At various times, she was a literary sculptor, at others a creator of portrait art - which she studied under Charles Grafly

Charles Allan Grafly, Jr. (December 3, 1862May 5, 1929) was an American sculptor, and teacher. Instructor of Sculpture at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for 37 years, his students included Paul Manship, Albin Polasek, and Walker Hanc ...

at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) is a museum and private art school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. as well as a scholarship for an additional year of study.

Upon graduation in 1899, Warrick traveled to

Warrick created works of the African-American experience that were revolutionary. They touched on the complexities of nature, religion, identity, and nation. She is considered part of the

Warrick created works of the African-American experience that were revolutionary. They touched on the complexities of nature, religion, identity, and nation. She is considered part of the

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, where she studied with Raphaël Collin

Louis-Joseph-Raphaël Collin (17 June 1850 – 21 October 1916) was a French painter born and raised in Paris, where he became a prominent academic painter and a teacher. He is principally known for the links he created between French and Japa ...

, working on sculpture and anatomy at the Académie Colarossi

The Académie Colarossi (1870–1930) was an art school in Paris founded in 1870 by the Italian model and sculptor Filippo Colarossi. It was originally located on the Île de la Cité, and it moved in 1879 to 10 rue de la Grande-Chaumière in the ...

and drawing at the École des Beaux-Arts

École des Beaux-Arts (; ) refers to a number of influential art schools in France. The term is associated with the Beaux-Arts style in architecture and city planning that thrived in France and other countries during the late nineteenth century ...

. Warrick had to deal with racial discrimination at the American Women's Club, where she was refused lodging although she had made reservations before arriving in the city. African-American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner

Henry Ossawa Tanner (June 21, 1859 – May 25, 1937) was an American artist and the first African-American painter to gain international acclaim. Tanner moved to Paris, France, in 1891 to study at the Académie Julian and gained acclaim in Fren ...

, a family friend, found lodging for her and gave her community amongst his group of friends.

Warrick's work grew stronger in Paris, where she studied until 1902. Influenced by the conceptual realism of Auguste Rodin

François Auguste René Rodin (12 November 184017 November 1917) was a French sculptor, generally considered the founder of modern sculpture. He was schooled traditionally and took a craftsman-like approach to his work. Rodin possessed a uniqu ...

, she became so adept at depicting the spirituality of human suffering that the French press named her "the delicate sculptor of horrors." In 1902, she became the protege of Rodin

François Auguste René Rodin (12 November 184017 November 1917) was a French sculptor, generally considered the founder of modern sculpture. He was schooled traditionally and took a craftsman-like approach to his work. Rodin possessed a uniqu ...

. Of her plaster sketch entitled ''Man Eating His Heart,'' Rodin remarked, "My child, you are a sculptor; you have the sense of form in your fingers."

Career

Warrick created works of the African-American experience that were revolutionary. They touched on the complexities of nature, religion, identity, and nation. She is considered part of the

Warrick created works of the African-American experience that were revolutionary. They touched on the complexities of nature, religion, identity, and nation. She is considered part of the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

, a flourishing in New York of African Americans making art of various genres, literature, plays and poetry. The Danforth Museum Danforth Art Museum at Framingham State University (formerly Danforth Museum of Art) is a museum and school in Framingham, Massachusetts. It is part of Framingham State University.

History

The Danforth Museum Corporation was established on Augus ...

, which received a $40,000 grant from the Henry Luce Foundation to safeguard Warrick Fuller's work, states that Fuller is "generally considered one of the first African-American female sculptors of importance."

Paris

In Paris, she met American sociologistW. E. B. DuBois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian Sociology, sociologist, Socialism, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanism, Pan-Africanist Civil and political civil rights activist. Bor ...

, who became a lifelong friend and confidant. He encouraged Warrick to draw from African and African-American themes in her work. She met French sculptor Auguste Rodin, who encouraged her sculpting. Her real mentor was Henry Ossawa Tanner while learning from Raphaël Collin

Louis-Joseph-Raphaël Collin (17 June 1850 – 21 October 1916) was a French painter born and raised in Paris, where he became a prominent academic painter and a teacher. He is principally known for the links he created between French and Japa ...

. It was the "masculinity and primitive power" of her sculptures that drew the French crowds to her work and generated her acclaim. The Paris crowd was astonished that a woman could produce works that depicted such "horror, pain, and sorrow." It was a relief for Warrick that her gender wasn't an inhibitor for how the public reacted to her racially themed pieces, as it would be in the United States. By the end of her time in Paris, she was widely known and had had her works exhibited in many galleries.

Samuel Bing, patron of Aubrey Beardsley

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley (21 August 187216 March 1898) was an English illustrator and author. His black ink drawings were influenced by Woodblock printing in Japan, Japanese woodcuts, and depicted the grotesque, the decadent, and the erotic. He ...

, Mary Cassatt

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (; May 22, 1844June 14, 1926) was an American painter and printmaker. She was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh's North Side), but lived much of her adult life in France, where she befriended Edgar De ...

, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Comte Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (24 November 1864 – 9 September 1901) was a French painter, printmaker, draughtsman, caricaturist and illustrator whose immersion in the colourful and theatrical life of Paris in the ...

, recognized her abilities by sponsoring a one-woman exhibition including Siegfried Bing

Samuel Siegfried Bing (26 February 1838 – 6 September 1905), who usually gave his name as S. Bing (not to be confused with his brother, Samuel Otto Bing, 1850–1905), was a German-French art dealer who lived in Paris as an adult, and who ...

's Salon de l'Art Nouveau (Maison de l'Art Nouveau). In 1903, just before Warrick returned to the United States, two of her works, ''The Wretched'' and ''The Impenitent Thief,'' were exhibited at the Paris Salon

The Salon (french: Salon), or rarely Paris Salon (French: ''Salon de Paris'' ), beginning in 1667 was the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Between 1748 and 1890 it was arguably the greatest annual or biennial art ...

.

United States

Returning to Philadelphia in 1903, Warrick was shunned by members of the Philadelphia art scene because of her race and because her art was considered "domestic." However, Fuller became the first African-American woman to receive a U.S. government commission. For this award, she created a series of tableaux depicting African-American historical events for the Jamestown Tercentennial Exposition, held in Norfolk, Virginia in 1907. The display included fourteen dioramas and 130 painted plaster figures depicting scenes such as slaves arriving in Virginia in 1619 and the home lives of black peoples. ''Mary Turner'' was her response to the 1918 lynching of a young, pregnant black woman inLowndes County, Georgia

Lowndes County is a county located in the south central portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2020 census the population was 118,251. The county seat is Valdosta. The county was created December 23, 1825.

Lowndes County is included ...

. Fuller's contemporary, Angelina Weld Grimké

Angelina Weld Grimké (February 27, 1880 – June 10, 1958) was an African-American journalist, teacher, playwright, and poet.

By ancestry, Grimké was three-quarters white — the child of a white mother and a half-white father — and consi ...

, wrote the short story "Goldie" based on this murder. Warrick's activism also spanned into feminist work. She participated in the Women's Peace Party and the Equal Suffrage Movement, but abruptly stopped once she realized that black women were not included in the fight for equal voting rights. She often sold pieces to fund voter registration campaigns in the South.

Warrick exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) is a museum and private art school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She exhibited there again in 1908. In 1910, a fire at a warehouse in Philadelphia, where she kept tools and stored numerous paintings and sculptures, destroyed her belongings; she lost 16 years' worth of work. Among her oeuvre, only a few early works stored elsewhere were preserved. The losses were emotionally devastating for her.

Fuller exhibited at the

Fuller exhibited at the

Exhibitions

1907 Jamestown Tercentennial

In February 1907, Warrick secured a contract to create 14 dioramas depicting the African-American experience. At the time, it was described as the "Historic Tableaux of the Negroes' Progress." Historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage has described Fuller's tableaux as one that suggested "the expansiveness of black abilities, aspirations and experiences, resentinga cogent alternative to white representations of history." Warrick's tableaux were given prominent display in the Negro Building at the Jamestown Tercentennial, where they occupied 15,000 square feet. Each scene consisted of painted plaster figures and extensive painted backdrops. The 14 tableaux depicted the following: the landing of the first slaves at Jamestown; slaves at work in a cotton field; a fugitive slave in hiding; a gathering of the firstAfrican Methodist Episcopal Church

The African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the AME Church or AME, is a Black church, predominantly African American Methodist Religious denomination, denomination. It adheres to Wesleyan-Arminian theology and has a connexionalism, c ...

; a slave defending his owner's home during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

; newly freed slaves building their own home; an independent black farmer, builder and contractor; a black businessman and banker; scenes inside a modern African-American home, church and school; and finally, a college commencement. For her work on the tableaux, Warrick was awarded a gold medal by the directors of the exposition.

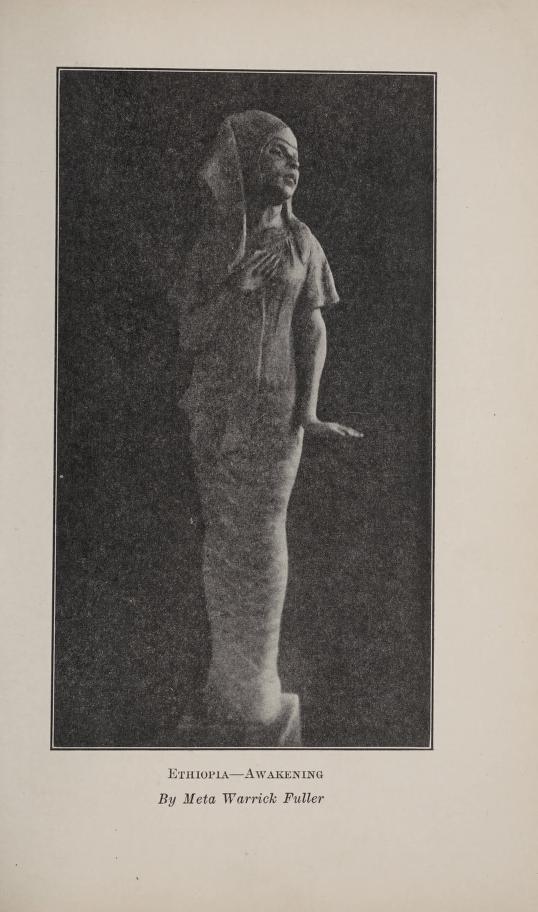

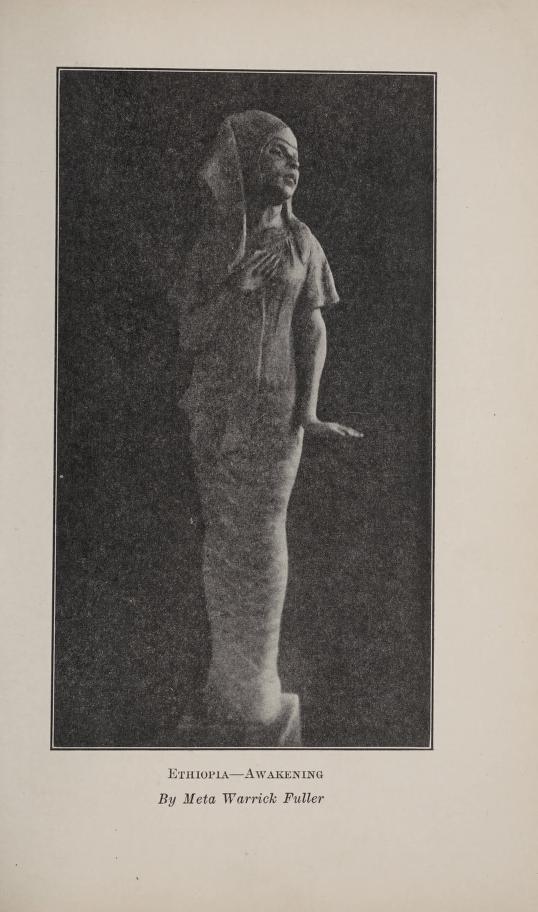

''Ethiopia'' and beyond

Fuller exhibited at the

Fuller exhibited at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) is a museum and private art school in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This event was meant to highlight immigrants' contributions to US artistic society and culture. This sculpture was featured in the exhibition's "colored section," and it symbolized a new black identity that was emerging through the Harlem Renaissance. It represented the pride of African Americans in African and black heritage and identity. ''Ethiopia'', drawn from Egyptian sculptural concepts, is an academic sculpture of an African woman emerging from a

* ''Bacchante,'' painted plaster sculpture, 1930

* ''Emancipation'', in plaster, 1913; in bronze, 1999. Featured on the

* ''Bacchante,'' painted plaster sculpture, 1930

* ''Emancipation'', in plaster, 1913; in bronze, 1999. Featured on the

Danforth Museum of Art. 11 May 2014. * ''La petite danseuse'', bronze sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art * ''Les Miserables,'' bronze sculpture, Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington * ''Lazy Bones in the Shade,'' sculpture, * ''Man Eating Out His Heart,'' painted plaster sculpture, 1905–1906. It represents a kneeling male nude eating his heart. * ''Mary Turner (A Silent Protest Against Mob Violence),'' painted plaster sculpture, 1919, Museum of Afro-American History, Boston, Massachusetts * ''Mother and Child,'' cast bronze sculpture, 1962, Massachusetts Institute of Technology * ''Peace Halting the Ruthlessness of War'', c.1917, renamed and unveiled as "Ravages of War" on October 15, 1999 at

SIRIS database search. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

"Meta Warrick Fuller"

''Unladylike2020''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Fuller, Meta Vaux Warrick American women sculptors 1877 births 1968 deaths Artists from Philadelphia University of the Arts (Philadelphia) alumni Académie Colarossi alumni American women poets American alumni of the École des Beaux-Arts African-American poets Harlem Renaissance 20th-century American sculptors 20th-century American women artists African-American sculptors Sculptors from Pennsylvania 20th-century African-American women 20th-century African-American artists African-American women writers

mummy

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay fu ...

's wrappings, like a chrysalis

A pupa ( la, pupa, "doll"; plural: ''pupae'') is the life stage of some insects undergoing transformation between immature and mature stages. Insects that go through a pupal stage are holometabolous: they go through four distinct stages in their ...

from a cocoon, represented her statement on black consciousness globally. Fuller made multiple versions of ''Ethiopia'', including a small maquette with the figure's left hand projecting from its body (now lost) and two full-size bronze casts, one with the left hand projecting and a second made incorrectly, with the left hand flush to the figure's side.

In 1922, Fuller showed her sculpture work at the Boston Public Library

The Boston Public Library is a municipal public library system in Boston, Massachusetts, United States, founded in 1848. The Boston Public Library is also the Library for the Commonwealth (formerly ''library of last recourse'') of the Commonweal ...

. Her work was included in an exhibition for the Tanner League, held in the studios of Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

The federal commissions kept her employed, but she did not receive as much encouragement in the US as she had in Paris. Fuller continued to exhibit her work until her last show (1961) at Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is classified among "R2: Doctoral Universities – High research activity" and accredited by the Middle States Commissi ...

(Washington, D.C.) in 1961.

Poetry

Her poem "Departure" was included in the 1991 collection ''Now is Your Time! The African-American Struggle for Freedom.'' :The time is near (reluctance laid aside) :I see the barque afloat upon the ebbing tide :While on the shores my friends and loved ones stand. :I wave to them a cheerful parting hand, :Then take my place withCharon

In Greek mythology, Charon or Kharon (; grc, Χάρων) is a psychopomp, the ferryman of Hades, the Greek underworld. He carries the souls of those who have been given funeral rites across the rivers Acheron and Styx, which separate the wo ...

at the helm,

:And turn and wave again to them.

:Oh, may the voyage not be arduous nor long,

:But echoing with chant and joyful song,

:May I behold with reverence and grace,

:The wondrous vision of the Master's face.

Theater

Warrick Fuller made significant contributions to theater. She was a multi-faceted designer, director, and actress. One of her focuses was stage lighting, which was not considered a true art form until the late 1920s; moreover, lighting design was dominated by men. Fuller was able to design for both African-American and white theater companies, which was unheard of at the time. In 1918, she joined theater organizations in Boston, Massachusetts. She was known for her paintings of "living pictures" as well as the creation of props, scenery, and masks. ''The Answer'' was an African-American stage production where Fuller designed costumes while also performing a small role. She became active in the Civic League Players (CLS) in the late 1920s and was the only African-American of the organization. With the CLS, Fuller worked on over thirty shows in all different areas of production and taught workshops. In 1928, she was taking theater classes at Wellesley College and Columbia University that focused on pageantry, lighting, and playwriting. After becoming less active in the CLS, Fuller joined a Black theater company called the Allied Arts Theatre Group (AATG) where she worked as a head designer, director, and board member. She was involved with the AATG until the founder's death in 1936. Even with her commitments of being an artist and working in theater, Fuller wrote at least six plays under the pseudonym, Danny Deaver. The following is an excerpt of stage directions in her production titled, ''A Call After Midnight'':"On the long hall table is a lamp, which the characters snap on and off, as they stop to look for mail, which is left in a receptacle for that purpose. The wall lights of the room are controlled by a switch at right of entrance, but these are of dull amber, the candle variety, the light is never bright."

Legacy

Warrick Fuller's work has received new interest since the late 20th century. Her work was featured in 1988 in a traveling exhibition at theCrocker Art Museum

The Crocker Art Museum is the oldest art museum in the Western United States, located in Sacramento, California. Founded in 1885, the museum holds one of the premier collections of Californian art. The collection includes American works dating f ...

, along with artists Aaron Douglas, Palmer C. Hayden and James Van Der Zee

James Augustus Van Der Zee (June 29, 1886 – May 15, 1983) was an American photographer best known for his portraits of black New Yorkers. He was a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Aside from the artistic merits of his work, Van Der Zee ...

. Her work was also featured in a traveling exhibition called ''Three Generations of African American Women Sculptors: A Study in Paradox,'' in Georgia in 1998.

The Danforth Museum Danforth Art Museum at Framingham State University (formerly Danforth Museum of Art) is a museum and school in Framingham, Massachusetts. It is part of Framingham State University.

History

The Danforth Museum Corporation was established on Augus ...

has a large collection of Fuller's sculptures, including many unfinished works from her home studio. Many were exhibited in a solo retrospective show of her work from November 2008 to May 2009.

Fuller's work was included in the 2015 exhibition '' We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s-1970s'' at the Woodmere Art Museum

Woodmere Art Museum, located in the Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has a collection of paintings, prints, sculpture and photographs focusing on artists from the Delaware Valley and includes works by Thomas Pollock Anshutz, S ...

.

Works

* ''Bacchante,'' painted plaster sculpture, 1930

* ''Emancipation'', in plaster, 1913; in bronze, 1999. Featured on the

* ''Bacchante,'' painted plaster sculpture, 1930

* ''Emancipation'', in plaster, 1913; in bronze, 1999. Featured on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail

The Boston Women's Heritage Trail is a series of walking tours in Boston, Massachusetts, leading past sites important to Boston women's history. The tours wind through several neighborhoods, including the Back Bay and Beacon Hill, commemorating w ...

.

* ''Ethiopia'', small maquette cast in plaster and painted to resemble bronze, c. 1921, 13 × 3 1/2 × 3 7/8 in., National Museum of African American History and Culture.

* ''Ethiopia Awakening,'' bronze sculpture, greenish-black patina, with hand incorrectly placed flush with the figure's side, , 67 x 16 x 20 in., Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

* ''Henry Gilbert,'' painted plaster sculpture, 1928

* ''Jason,'' painted plaster sculpture, Danfort Museum''Meta Warrick Fuller : Sculptures from the Studio.''Danforth Museum of Art. 11 May 2014. * ''La petite danseuse'', bronze sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art * ''Les Miserables,'' bronze sculpture, Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, Washington * ''Lazy Bones in the Shade,'' sculpture, * ''Man Eating Out His Heart,'' painted plaster sculpture, 1905–1906. It represents a kneeling male nude eating his heart. * ''Mary Turner (A Silent Protest Against Mob Violence),'' painted plaster sculpture, 1919, Museum of Afro-American History, Boston, Massachusetts * ''Mother and Child,'' cast bronze sculpture, 1962, Massachusetts Institute of Technology * ''Peace Halting the Ruthlessness of War'', c.1917, renamed and unveiled as "Ravages of War" on October 15, 1999 at

West Virginia State College

West Virginia State University (WVSU) is a public historically black, land-grant university in Institute, West Virginia. Founded in 1891 as the West Virginia Colored Institute, it is one of the original 19 land-grant colleges and universities ...

"'Ravages' Unveiling Oct. 15 at WVSC." ''The Charleston Gazette,'' Oct 14, 1999.

* ''Phyllis Wheatley (c. 1753-1784),'' painted plaster sculpture, . It was made based upon an engraving published in 1773

* ''Refugee, sculpture'', . Hunched male figure with a cane in his hand

* ''Talking Skull,'' bronze sculpture, 1937, Museum of Afro-American History, Boston, Massachusetts. Kneeling male figure facing a skull

* ''The Good Shepherd,'' painted plaster sculpture,

* ''Waterboy,'' sculpture, 1930''Meta Warrick Fuller.''SIRIS database search. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

See also

*Lois Mailou Jones

Lois Mailou Jones (1905-1998) was an artist and educator. Her work can be found in the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum o ...

* Sargent Claude Johnson

Sargent Claude Johnson (October 7, 1888 – October 10, 1967) was one of the first African-American artists working in California to achieve a national reputation.

* Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Armstead Lawrence (September 7, 1917 – June 9, 2000) was an American painter known for his portrayal of African-American historical subjects and contemporary life. Lawrence referred to his style as "dynamic cubism", although by his own ...

* Archibald Motley

Archibald John Motley, Jr. (October 7, 1891 – January 16, 1981), was an American visual artist. He studied painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago during the 1910s, graduating in 1918. Motley is most famous for his colorful chroni ...

* Romare Bearden

Romare Bearden (September 2, 1911 – March 12, 1988) was an American artist, author, and songwriter. He worked with many types of media including cartoons, oils, and collages. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, Bearden grew up in New York City a ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* Ater, Renée. ''Remaking Race and History: The Sculpture of Meta Warrick Fuller.'' Berkeley: University of California Press. 2011. * * * Driskell, David C. et al. ''Harlem Renaissance: Art of Black America,'' New York, 1994. * Igoe, Lynn Moody with James Igoe, ''250 years of Afro-American Art: An Annotated Bibliography''. New York: Bowker, 1981. * ''An Independent Woman: The Life and Art of Meta Warrick Fuller (1877-1968).'' Framingham, MA: Danforth Museum of Art. 1984. Exhibition catalogue. * Kerr, N. ''God-Given Work: The Life and Times of Sculptor Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, 1877-1968,'' Amherst, 1987. * King-Hammond, L. et al. ''3 Generations of African American Women Sculptors: A Study in Paradox,'' Philadelphia, 1996. * * Powell, Richard J. and David A. Bailey. ''Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance,'' 1997.External links

"Meta Warrick Fuller"

''Unladylike2020''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Fuller, Meta Vaux Warrick American women sculptors 1877 births 1968 deaths Artists from Philadelphia University of the Arts (Philadelphia) alumni Académie Colarossi alumni American women poets American alumni of the École des Beaux-Arts African-American poets Harlem Renaissance 20th-century American sculptors 20th-century American women artists African-American sculptors Sculptors from Pennsylvania 20th-century African-American women 20th-century African-American artists African-American women writers