Mennonitism In The United States on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mennonites are groups of

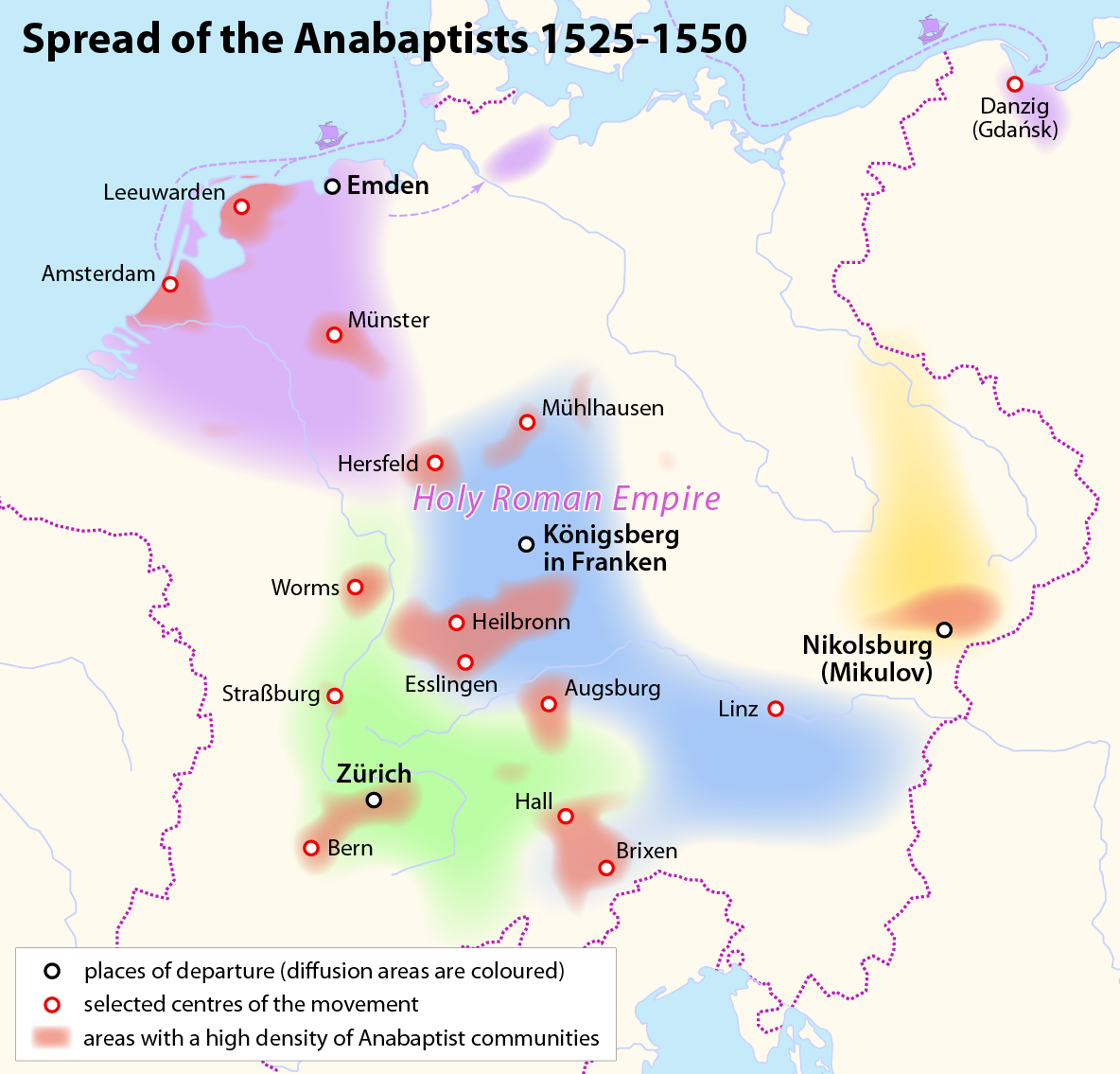

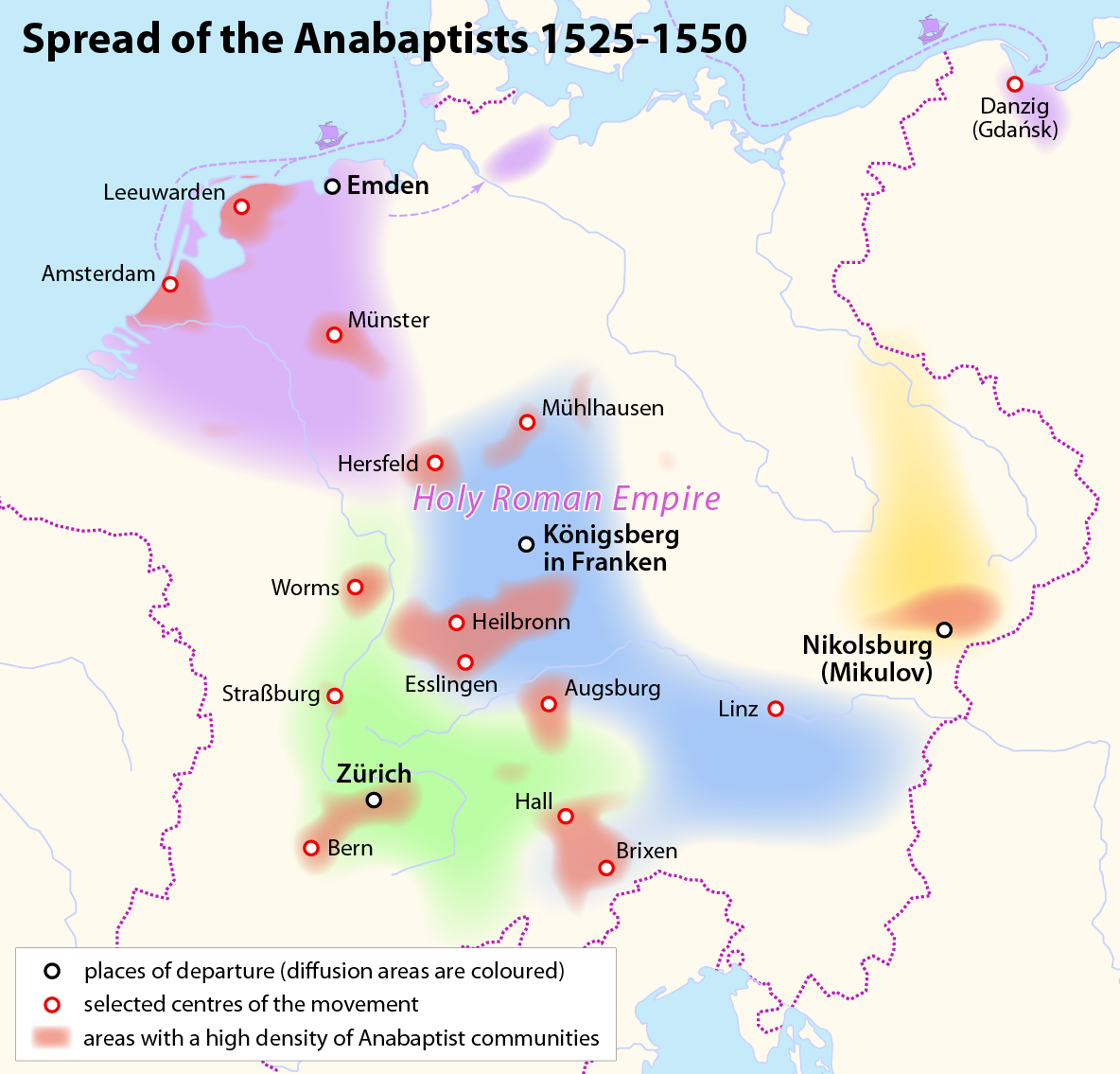

The early history of the Mennonites starts with the Anabaptists in the German and Dutch-speaking regions of central Europe. The German term is ''Täufer'' or ''Wiedertäufer'' ("Again-Baptists" or "Anabaptists" using the Greek ''ana'' again". These forerunners of modern Mennonites were part of the

The early history of the Mennonites starts with the Anabaptists in the German and Dutch-speaking regions of central Europe. The German term is ''Täufer'' or ''Wiedertäufer'' ("Again-Baptists" or "Anabaptists" using the Greek ''ana'' again". These forerunners of modern Mennonites were part of the  In the early days of the Anabaptist movement,

In the early days of the Anabaptist movement,

During the 16th century, the Mennonites and other Anabaptists were relentlessly

During the 16th century, the Mennonites and other Anabaptists were relentlessly

Persecution and the search for employment forced Mennonites out of the Netherlands eastward to Germany in the 17th century. As

Persecution and the search for employment forced Mennonites out of the Netherlands eastward to Germany in the 17th century. As

1780s–1790s

* St. Jacobs, Ontario c.1819 *

During

During

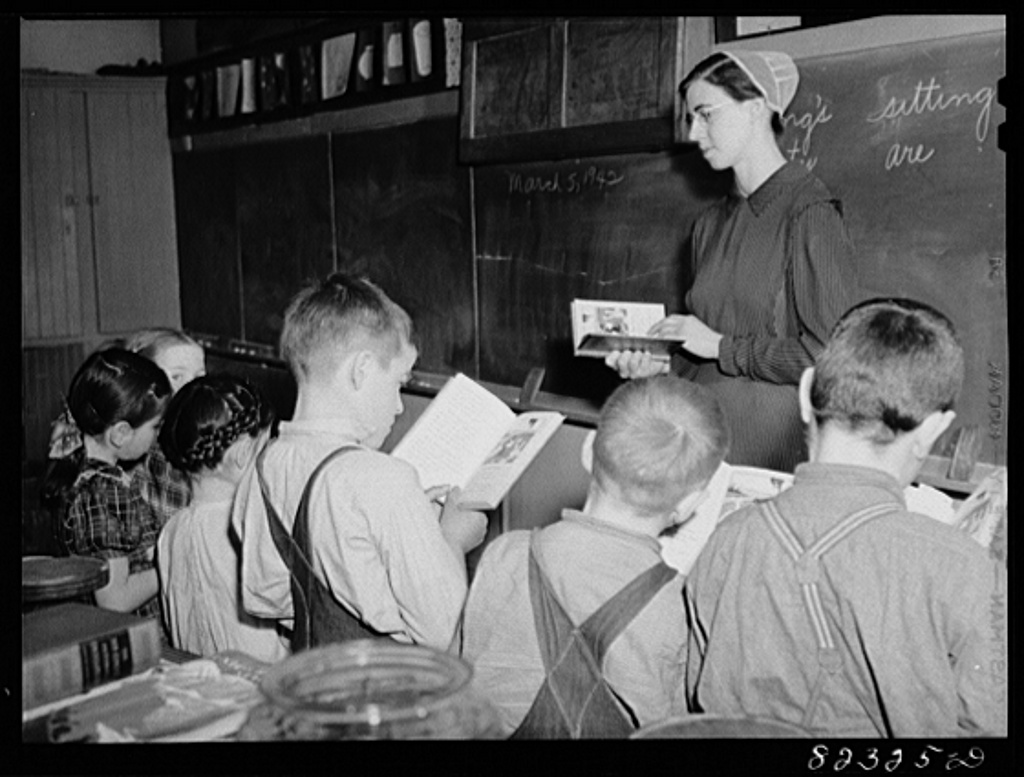

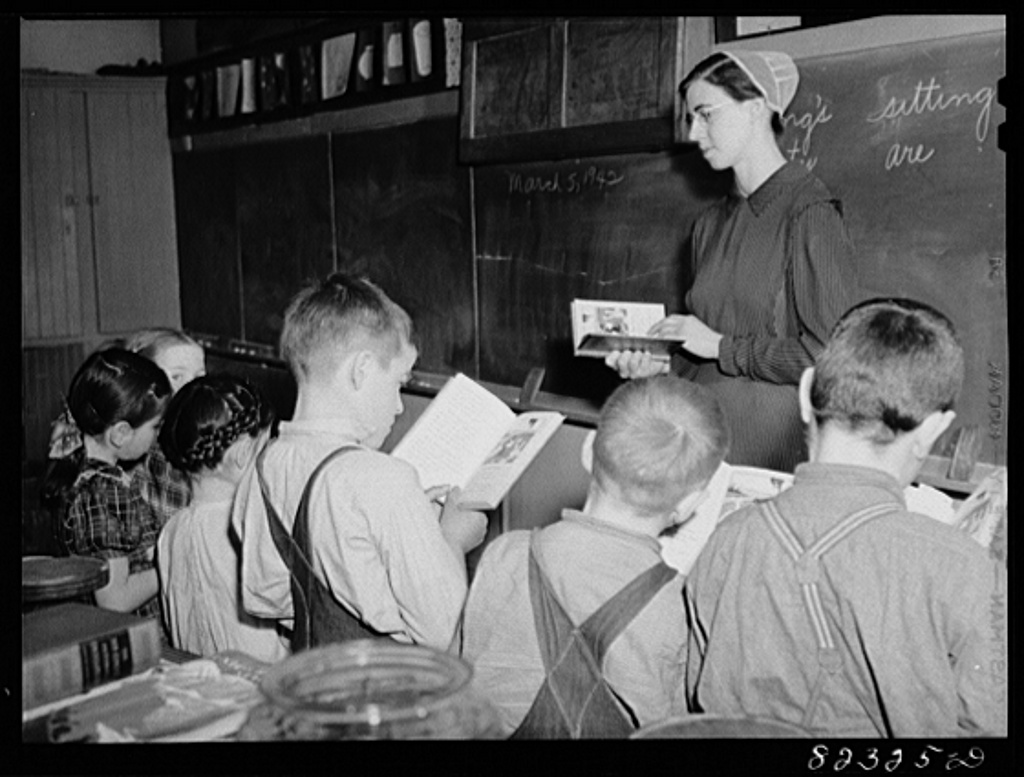

Several Mennonite groups established schools, universities and seminaries.Conservative groups, like the Holdeman, have not only their own schools, but their own curriculum and teaching staff (usually, but not exclusively, young unmarried women).

Several Mennonite groups established schools, universities and seminaries.Conservative groups, like the Holdeman, have not only their own schools, but their own curriculum and teaching staff (usually, but not exclusively, young unmarried women).

According to a 2018 census by the

According to a 2018 census by the

The most basic unit of organization among Mennonites is the church. There are hundreds or thousands of Mennonite churches and groups, many of which are separate from all others. Some churches are members of regional or area conferences. And some regional or area conferences are affiliated with larger national or international conferences. There is no single world authority on among Mennonites, however there is a Mennonite World Committee (MWC) includes Mennonites from 53 countries. The MWC does not make binding decisions on behalf of members but coordinates Mennonite causes aligning with the MWC's shared convictions.

For the most part, there is a host of independent Mennonite churches along with a myriad of separate conferences with no particular responsibility to any other group. Independent churches can contain as few as fifty members or as many as 20,000 members. Similar size differences occur among separate conferences. Worship, church discipline and lifestyles vary widely between progressive, moderate, conservative, Old Order and orthodox Mennonites in a vast panoply of distinct, independent, and widely dispersed classifications. There is no central authority that claims to speak for all Mennonites, as the 20th century passed, cultural distinctiveness between Mennonite groups has decreased.

The twelve largest Mennonite/Anabaptist groups are:

#

The most basic unit of organization among Mennonites is the church. There are hundreds or thousands of Mennonite churches and groups, many of which are separate from all others. Some churches are members of regional or area conferences. And some regional or area conferences are affiliated with larger national or international conferences. There is no single world authority on among Mennonites, however there is a Mennonite World Committee (MWC) includes Mennonites from 53 countries. The MWC does not make binding decisions on behalf of members but coordinates Mennonite causes aligning with the MWC's shared convictions.

For the most part, there is a host of independent Mennonite churches along with a myriad of separate conferences with no particular responsibility to any other group. Independent churches can contain as few as fifty members or as many as 20,000 members. Similar size differences occur among separate conferences. Worship, church discipline and lifestyles vary widely between progressive, moderate, conservative, Old Order and orthodox Mennonites in a vast panoply of distinct, independent, and widely dispersed classifications. There is no central authority that claims to speak for all Mennonites, as the 20th century passed, cultural distinctiveness between Mennonite groups has decreased.

The twelve largest Mennonite/Anabaptist groups are:

#

In 2015, there were 538,839 baptized members organized into 41 bodies in United States, according to the Mennonite World Conference. The largest group of that number is the Old Order Amish, perhaps numbering as high as 300,000. The

In 2015, there were 538,839 baptized members organized into 41 bodies in United States, according to the Mennonite World Conference. The largest group of that number is the Old Order Amish, perhaps numbering as high as 300,000. The

Germany has the largest contingent of Mennonites in Europe. The Mennonite World Conference counts 47,202 baptized members within 7 organized bodies in 2015. The largest group is the ''Bruderschaft der Christengemeinde in Deutschland'' (Mennonite Brethren), which had 20,000 members in 2010. Another such body is the Union of German Mennonite Congregations or ''Vereinigung der Deutschen Mennonitengemeinden''. Founded in 1886, it has 27 Congregations with 5,724 members and is part of the larger "Arbeitsgemeinschaft Mennonitischer Gemeinden in Deutschland" or AMG (Assembly/Council of Mennonite Churches in Germany), which claims 40,000 overall members from various groups. Other AMG member groups include: ''Rußland-Deutschen Mennoniten'', ''Mennoniten-Brüdergemeinden''(Independent Mennonite Brethren congregations), ''WEBB-Gemeinden'', and the ''Mennonitischen Heimatmission''. However, not all German Mennonites belong to this larger AMG body. Upwards of 40,000 Mennonites emigrated from Russia to Germany starting in the 1970s.

The Mennonite presence remaining in the Netherlands, ''Algemene Doopsgezinde Societeit'' or ADS (translated as ''General Mennonite Society''), maintains a seminary, as well as organizing relief, peace, and mission work, the latter primarily in Central Java and New Guinea. They have 121 congregations with 10,200 members according to the World Council of Churches, although the Mennonite World Conference cites only 7680 members.

Switzerland had 2350 Mennonites belonging to 14 Congregations which are part of the ''Konferenz der Mennoniten der Schweiz (Alttäufer), Conférence mennonite suisse (Anabaptiste)'' (Swiss Mennonite Conference).

In 2015, there were 2078 Mennonites in France. The country's 32 autonomous Mennonite congregations have formed the ''Association des Églises Évangéliques Mennonites de France''.

While Ukraine was once home to tens of thousands of Mennonites, in 2015 the number totalled just 499. They are organized among three denominations: ''Association of Mennonite Brethren Churches of Ukraine'', ''Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (Ukraine)'', and ''Evangelical Mennonite Churches of Ukraine (Beachy Amish Church – Ukraine)''.

The U.K. had but 326 members within two organized bodies as of 2015. There is the Nationwide Fellowship Churches (UK) and the larger Brethren in Christ Church United Kingdom. Additionally, there is the registered charity, ''The Mennonite Trust'' (formerly known as "London Mennonite Centre"), which seeks to promote understanding of Mennonite and Anabaptist practices and values.

Germany has the largest contingent of Mennonites in Europe. The Mennonite World Conference counts 47,202 baptized members within 7 organized bodies in 2015. The largest group is the ''Bruderschaft der Christengemeinde in Deutschland'' (Mennonite Brethren), which had 20,000 members in 2010. Another such body is the Union of German Mennonite Congregations or ''Vereinigung der Deutschen Mennonitengemeinden''. Founded in 1886, it has 27 Congregations with 5,724 members and is part of the larger "Arbeitsgemeinschaft Mennonitischer Gemeinden in Deutschland" or AMG (Assembly/Council of Mennonite Churches in Germany), which claims 40,000 overall members from various groups. Other AMG member groups include: ''Rußland-Deutschen Mennoniten'', ''Mennoniten-Brüdergemeinden''(Independent Mennonite Brethren congregations), ''WEBB-Gemeinden'', and the ''Mennonitischen Heimatmission''. However, not all German Mennonites belong to this larger AMG body. Upwards of 40,000 Mennonites emigrated from Russia to Germany starting in the 1970s.

The Mennonite presence remaining in the Netherlands, ''Algemene Doopsgezinde Societeit'' or ADS (translated as ''General Mennonite Society''), maintains a seminary, as well as organizing relief, peace, and mission work, the latter primarily in Central Java and New Guinea. They have 121 congregations with 10,200 members according to the World Council of Churches, although the Mennonite World Conference cites only 7680 members.

Switzerland had 2350 Mennonites belonging to 14 Congregations which are part of the ''Konferenz der Mennoniten der Schweiz (Alttäufer), Conférence mennonite suisse (Anabaptiste)'' (Swiss Mennonite Conference).

In 2015, there were 2078 Mennonites in France. The country's 32 autonomous Mennonite congregations have formed the ''Association des Églises Évangéliques Mennonites de France''.

While Ukraine was once home to tens of thousands of Mennonites, in 2015 the number totalled just 499. They are organized among three denominations: ''Association of Mennonite Brethren Churches of Ukraine'', ''Church of God in Christ, Mennonite (Ukraine)'', and ''Evangelical Mennonite Churches of Ukraine (Beachy Amish Church – Ukraine)''.

The U.K. had but 326 members within two organized bodies as of 2015. There is the Nationwide Fellowship Churches (UK) and the larger Brethren in Christ Church United Kingdom. Additionally, there is the registered charity, ''The Mennonite Trust'' (formerly known as "London Mennonite Centre"), which seeks to promote understanding of Mennonite and Anabaptist practices and values.

Mennonite Religion was a Family Religion': A Historiography,"

''Journal of Mennonite Studies'' (2005), Vol. 23 pp. 9–22. * Hinojosa, Felipe (2014). ''Latino Mennonites: Civil Rights, Faith, and Evangelical Culture.'' Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. * Horsch, James E. (Ed.) (1999), ''Mennonite Directory'', Herald Press. * Kinberg, Clare. "Mennonites." om ''Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America,'' edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 3, Gale, 2014), pp. 171–182

Online

* Pamela Klassen, Klassen, Pamela E. ''Going by the Moon and the Stars: Stories of Two Russian Mennonite Women''. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1994. * Krahn, Cornelius, Gingerich, Melvin & Harms, Orlando (Eds.) (1955). ''The Mennonite Encyclopedia'', Volume I, pp. 76–78. Mennonite Publishing House. * Kraybill, D. B. ''Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites'' (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010). * Mennonite & Brethren in Christ World Directory 2003. Available On-line a

MWC – World Directory

* Pannabecker, Samuel Floyd (1975), ''Open Doors: A History of the General Conference Mennonite Church'', Faith and Life Press. * * Stephen Scott (writer), Scott, Stephen (1995), ''An Introduction to Old Order and Conservative Mennonite Groups'', Good Books, * Smith, C. Henry (1981), ''Smith's Story of the Mennonites'' (5th ed. Faith and Life Press). * Van Braght, Thielman J. (1660), ''Martyrs Mirror'' (2nd English ed. Herald Press)

Lancaster Mennonite Historical Society, in Pennsylvania

*

Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online (GAMEO)

Global Anabaptist Wiki

Mennonite World Conference

Pilgrim Ministry: Conservative Mennonite church directory

The Swiss Mennonite Cultural and Historical Association

* {{Authority control Mennonites, Mennonitism, Christian pacifism Christianity in Ohio Mennonite denominations Mennonitism in the United States Peace churches Pennsylvania culture Protestant denominations established in the 16th century Protestantism in Indiana Anabaptism in Pennsylvania Religion in Lancaster, Pennsylvania Religious abstentions Religious organizations established in the 1530s Simple living

Anabaptist

Anabaptism (from New Latin language, Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re- ...

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

church communities of denominations. The name is derived from the founder of the movement, Menno Simons

Menno Simons (1496 – 31 January 1561) was a Roman Catholic priest from the Friesland region of the Low Countries who was excommunicated from the Catholic Church and became an influential Anabaptist religious leader. Simons was a contemporary o ...

(1496–1561) of Friesland

Friesland (, ; official fry, Fryslân ), historically and traditionally known as Frisia, is a province of the Netherlands located in the country's northern part. It is situated west of Groningen, northwest of Drenthe and Overijssel, north of ...

. Through his writings about Reformed Christianity

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Calv ...

during the Radical Reformation

The Radical Reformation represented a response to corruption both in the Catholic Church and in the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland in the 16th century, the Ra ...

, Simons articulated and formalized the teachings of earlier Swiss founders, with the early teachings of the Mennonites founded on the belief in both the mission and ministry of Jesus

The ministry of Jesus, in the canonical gospels, begins with his baptism in the countryside of Roman Judea and Transjordan, near the River Jordan by John the Baptist, and ends in Jerusalem, following the Last Supper with his disciples.''Chri ...

, which the original Anabaptist followers held with great conviction, despite persecution by various Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

and Mainline Protestant

The mainline Protestant churches (also called mainstream Protestant and sometimes oldline Protestant) are a group of Protestant denominations in the United States that contrast in history and practice with evangelical, fundamentalist, and charis ...

states. Formal Mennonite beliefs were codified in the Dordrecht Confession of Faith

The Dordrecht Confession of Faith is a statement of religious beliefs adopted by Dutch Mennonite leaders at a meeting in Dordrecht, the Netherlands, on 21 April 1632. Its 18 articles emphasize belief in salvation through Jesus Christ, baptism, ...

in 1632, which affirmed "the baptism of believers only, the washing of the feet as a symbol of servanthood, church discipline, the shunning of the excommunicated, the non-swearing of oaths, marriage within the same church, strict pacifistic physical nonresistance Nonresistance (or non-resistance) is "the practice or principle of not resisting authority, even when it is unjustly exercised". At its core is discouragement of, even opposition to, physical resistance to an enemy. It is considered as a form of pri ...

, anti-Catholicism

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestant states, including England, Prussia, Scotland, and the Uni ...

and in general, more emphasis on "true Christianity" involving "being Christian and obeying Christ" however they interpret it from the Holy Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

.

The majority of the early Mennonite followers, rather than fighting, survived by fleeing to neighboring states where ruling families were tolerant of their belief in believer's baptism

Believer's baptism or adult baptism (occasionally called credobaptism, from the Latin word meaning "I believe") is the practice of baptizing those who are able to make a conscious profession of faith, as contrasted to the practice of baptizing ...

. Over the years, Mennonites have become known as one of the historic peace churches

Peace churches are Christian churches, groups or communities advocating Christian pacifism or Biblical nonresistance. The term historic peace churches refers specifically only to three church groups among pacifist churches:

* Church of the Brethr ...

, due to their commitment to pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

.

Congregations worldwide embody the full scope of Mennonite practice, from Old Order Mennonite

Old Order Mennonites (Pennsylvania Dutch language, Pennsylvania German: ) form a branch of the Mennonite tradition. Old Order Movement, Old Order are those Mennonite groups of Swiss people, Swiss German and south Germans, German heritage who pract ...

s (who practice a lifestyle without certain elements of modern technology) to Conservative Mennonites

Conservative Mennonites include numerous Conservative Anabaptist groups that identify with the theologically conservative element among Mennonite Anabaptist Christian fellowships, but who are not Old Order groups or mainline denominations.

Con ...

(who hold to traditional theological distinctives, wear plain dress

Plain dress is a practice among some religious groups, primarily some Christian churches in which people dress in clothes of traditional modest design, sturdy fabric, and conservative cut. It is intended to show acceptance of traditional gender ...

and use modern conveniences) to mainline Mennonites (those who are indistinguishable in dress and appearance from the general population). Mennonites can be found in communities in 87 countries on six continents. Seven ordinances have been taught in many traditional Mennonite churches, which include "baptism, communion, footwashing, marriage, anointing with oil, the holy kiss, and the prayer covering." The largest populations of Mennonites are found in Canada, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, and the United States. There are Mennonite colonies in Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Colombia. The Mennonite Church in the Netherlands

The Mennonite Church in the Netherlands, or ''Algemene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit'', is a body of Mennonite Christians in the Netherlands.

The Mennonites (or Mennisten or Doopsgezinden) are named for Menno Simons (1496–1561), a Dutch Roman Catholi ...

still continues where Simons was born.

Though Mennonites are a global denomination with church membership from Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas, certain Mennonite communities with ethno-cultural origins in Switzerland and the Netherlands bear the designation of ethnic Mennonites

The term ethnic Mennonite refers to Mennonites of Central European ancestry and culture who are considered to be members of a Mennonite ethnic or ethnoreligious group. The term is also used for aspects of their culture, such as language, dress, and ...

.

History

The early history of the Mennonites starts with the Anabaptists in the German and Dutch-speaking regions of central Europe. The German term is ''Täufer'' or ''Wiedertäufer'' ("Again-Baptists" or "Anabaptists" using the Greek ''ana'' again". These forerunners of modern Mennonites were part of the

The early history of the Mennonites starts with the Anabaptists in the German and Dutch-speaking regions of central Europe. The German term is ''Täufer'' or ''Wiedertäufer'' ("Again-Baptists" or "Anabaptists" using the Greek ''ana'' again". These forerunners of modern Mennonites were part of the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, a broad reaction against the practices and theology of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Its most distinguishing feature is the rejection of infant baptism

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

, an act that had both religious and political meaning since almost every infant born in western Europe was baptized in the Roman Catholic Church. Other significant theological views of the Mennonites developed in opposition to Roman Catholic views or to the views of Protestant reformers such as Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

and Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Unive ...

.

Some of the followers of Zwingli's Reformed church

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

thought that requiring church membership beginning at birth was inconsistent with the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

example. They believed that the church should be completely removed from government (the proto–free church

A free church is a Christian denomination that is intrinsically separate from government (as opposed to a state church). A free church does not define government policy, and a free church does not accept church theology or policy definitions fr ...

tradition), and that individuals should join only when willing to publicly acknowledge belief in Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

and the desire to live in accordance with his teachings. At a small meeting in Zurich on January 21, 1525, Conrad Grebel

Conrad Grebel (c. 1498 – 1526), son of a prominent Swiss merchant and councilman, was a co-founder of the Swiss Brethren movement.

Early life

Conrad Grebel was born, probably in Grüningen in the Canton of Zurich, about 1498 to Junker Jako ...

, Felix Manz

Felix Manz (also Felix Mantz) (c. 1498 – 5 January 1527) was an Anabaptist, a co-founder of the original Swiss Brethren congregation in Zürich, Switzerland, and the first martyr of the Radical Reformation.

Birth and life

Manz was born an ...

, and George Blaurock

Jörg vom Haus Jacob (Georg Cajacob, or George of the House of Jacob), commonly known as George Blaurock (c. 1491 – September 6, 1529), was an Anabaptist leader and evangelist. Along with Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz, he was a co-founder ...

, along with twelve others, baptized each other. This meeting marks the beginning of the Anabaptist movement. In the spirit of the times, other groups came to preach about reducing hierarchy, relations with the state, eschatology

Eschatology (; ) concerns expectations of the end of the present age, human history, or of the world itself. The end of the world or end times is predicted by several world religions (both Abrahamic and non-Abrahamic), which teach that negati ...

, and sexual license, running from utter abandon to extreme chastity

Chastity, also known as purity, is a virtue related to temperance. Someone who is ''chaste'' refrains either from sexual activity considered immoral or any sexual activity, according to their state of life. In some contexts, for example when mak ...

. These movements are together referred to as the "Radical Reformation

The Radical Reformation represented a response to corruption both in the Catholic Church and in the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland in the 16th century, the Ra ...

".

Many government and religious leaders, both Protestant and Roman Catholic, considered voluntary church membership to be dangerous—the concern of some deepened by reports of the Münster Rebellion

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state distr ...

, led by a violent sect of Anabaptists. They joined forces to fight the movement, using methods such as banishment, torture, burning, drowning or beheading.

Despite strong repressive efforts of the state churches, the movement spread slowly around western Europe, primarily along the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

. Officials killed many of the earliest Anabaptist leaders in an attempt to purge Europe of the new sect. By 1530, most of the founding leaders had been killed for refusing to renounce their beliefs. Many believed that God did not condone killing or the use of force for any reason and were, therefore, unwilling to fight for their lives. The non-resistant branches often survived by seeking refuge in neutral cities or nations, such as Strasbourg

Strasbourg (, , ; german: Straßburg ; gsw, label=Bas Rhin Alsatian, Strossburi , gsw, label=Haut Rhin Alsatian, Strossburig ) is the prefecture and largest city of the Grand Est region of eastern France and the official seat of the Eu ...

. Their safety was often tenuous, as a shift in alliances or an invasion could mean resumed persecution. Other groups of Anabaptists, such as the Batenburgers

The Batenburgers were members of a radical Anabaptist sect led by Jan van Batenburg, that flourished briefly in the 1530s in the Netherlands, in the aftermath of the Münster Rebellion. They were called Zwaardgeesten (sword-minded) by the nonvio ...

, were eventually destroyed by their willingness to fight. This played a large part in the evolution of Anabaptist theology. They believed that Jesus taught that any use of force to get back at anyone was wrong, and taught to forgive.

In the early days of the Anabaptist movement,

In the early days of the Anabaptist movement, Menno Simons

Menno Simons (1496 – 31 January 1561) was a Roman Catholic priest from the Friesland region of the Low Countries who was excommunicated from the Catholic Church and became an influential Anabaptist religious leader. Simons was a contemporary o ...

, a Catholic priest in the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, heard of the movement and started to rethink his Catholic faith. He questioned the doctrine of transubstantiation

Transubstantiation (Latin: ''transubstantiatio''; Greek: μετουσίωσις ''metousiosis'') is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of th ...

but was reluctant to leave the Roman Catholic Church. His brother, a member of an Anabaptist group, was killed when he and his companions were attacked and refused to defend themselves. In 1536, at the age of 40, Simons left the Roman Catholic Church. He soon became a leader within the Anabaptist movement and was wanted by authorities for the rest of his life. His name became associated with scattered groups of nonviolent Anabaptists whom he helped to organize and consolidate.

Fragmentation and variation

During the 16th century, the Mennonites and other Anabaptists were relentlessly

During the 16th century, the Mennonites and other Anabaptists were relentlessly persecuted

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these terms ...

. This period of persecution has had a significant impact on Mennonite identity. ''Martyrs Mirror

''Martyr's Mirror'' or ''The Bloody Theater'', first published in Holland in 1660 in Dutch by Thieleman J. van Braght, documents the stories and testimonies of Christian martyrs, especially Anabaptists. The full title of the book is ''The Bloody ...

'', published in 1660, documents much of the persecution of Anabaptists and their predecessors, including accounts of over 4,000 burnings of individuals, and numerous stoning

Stoning, or lapidation, is a method of capital punishment where a group throws stones at a person until the subject dies from blunt trauma. It has been attested as a form of punishment for grave misdeeds since ancient times.

The Torah and Ta ...

s, imprisonment

Imprisonment is the restraint of a person's liberty, for any cause whatsoever, whether by authority of the government, or by a person acting without such authority. In the latter case it is "false imprisonment". Imprisonment does not necessari ...

s, and live burials. Today, the book is still the most important book besides the Bible for many Mennonites and Amish, in particular for the Swiss-South German branch of the Mennonites. Persecution was still going on until 1710 in various parts of Switzerland.

In 1693, Jakob Ammann

Jakob Ammann (also Jacob Amman, Amann; 12 February 1644 – between 1712 and 1730) was an Anabaptist leader and namesake of the Amish religious movement.

Personal life

The full facts about the personal life of Jacob Ammann are incomplete ...

led an effort to reform the Mennonite church in Switzerland and South Germany to include shunning

Shunning can be the act of social rejection, or emotional distance. In a religious context, shunning is a formal decision by a denomination or a congregation to cease interaction with an individual or a group, and follows a particular set of rule ...

, to hold communion more often, and other differences. When the discussions fell through, Ammann and his followers split from the other Mennonite congregations. Ammann's followers became known as the Amish

The Amish (; pdc, Amisch; german: link=no, Amische), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptist Christian church fellowships with Swiss German and Alsatian origins. They are closely related to Mennonite churches ...

Mennonites or just Amish. In later years, other schisms among Amish resulted in such groups as the Old Order Amish

The Amish (; pdc, Amisch; german: link=no, Amische), formally the Old Order Amish, are a group of traditionalist Anabaptist Christian church fellowships with Swiss German and Alsatian origins. They are closely related to Mennonite church ...

, New Order Amish

The New Order Amish are a subgroup of Amish that split away from the Old Order Amish in the 1960s for a variety of reasons, which included a desire for "clean" youth courting standards, meaning they do not condone the practice of bundling, or non ...

, Kauffman Amish Mennonite

The Kauffman Amish Mennonites, also called Sleeping Preacher Churches or Tampico Amish Mennonite Churches, are a plain, car-driving branch of the Amish Mennonites whose tradition goes back to John D. Kauffman (1847-1913) who preached while being ...

, Swartzentruber Amish The Swartzentruber Amish are the best-known and one of the largest and most conservative subgroups of Old Order Amish. Swartzentruber Amish are considered a subgroup of the Old Order Amish, although they do not fellowship or intermarry with more li ...

, Conservative Mennonite Conference

The Conservative Mennonite Conference (CMC) is a Christian body of Mennonite churches in the Anabaptist tradition. Its members are mostly of Amish descent.

Despite its name, the Conservative Mennonite Conference is not generally considered to ali ...

and Biblical Mennonite Alliance __NOTOC__

Biblical Mennonite Alliance (BMA) is an organization of Conservative Mennonite Anabaptist congregations located primarily in the eastern two thirds of the US and Canada, with some international affiliates. The BMA congregations are organ ...

. For instance, near the beginning of the 20th century, some members in the Amish church wanted to begin having Sunday school

A Sunday school is an educational institution, usually (but not always) Christian in character. Other religions including Buddhism, Islam, and Judaism have also organised Sunday schools in their temples and mosques, particularly in the West.

Su ...

s and participate in progressive Protestant-style para-church evangelism. Unable to persuade the rest of the Amish, they separated and formed a number of separate groups including the Conservative Mennonite Conference. Mennonites in Canada and other countries typically have independent denominations because of the practical considerations of distance and, in some cases, language. Many times these divisions took place along family lines, with each extended family supporting its own branch.

Political rulers often admitted the Menists or Mennonites into their states because they were honest, hardworking and peaceful. When their practices upset the powerful state churches, princes would renege on exemptions for military service, or a new monarch would take power, and the Mennonites would be forced to flee again, usually leaving everything but their families behind. Often, another monarch in another state would grant them welcome, at least for a while.

While Mennonites in Colonial America

The colonial history of the United States covers the history of European colonization of North America from the early 17th century until the incorporation of the Thirteen Colonies into the United States after the Revolutionary War. In the ...

were enjoying considerable religious freedom, their counterparts in Europe continued to struggle with persecution and temporary refuge under certain ruling monarchs. They were sometimes invited to settle in areas of poor soil that no one else could farm. By contrast, in the Netherlands, the Mennonites enjoyed a relatively high degree of tolerance. Because the land still needed to be tended, the ruler would not drive out the Mennonites but would pass laws to force them to stay, while at the same time severely limiting their freedom. Mennonites had to build their churches facing onto back streets or alleys, and they were forbidden from announcing the beginning of services with the sound of a bell.

A strong emphasis on "community" was developed under these circumstances. It continues to be typical of Mennonite churches. As a result of frequently being required to give up possessions in order to retain individual freedoms, Mennonites learned to live very simply. This was reflected both in the home and at church, where their dress and their buildings were plain. The music at church, usually simple German chorales, was performed ''a cappella

''A cappella'' (, also , ; ) music is a performance by a singer or a singing group without instrumental accompaniment, or a piece intended to be performed in this way. The term ''a cappella'' was originally intended to differentiate between Ren ...

''. This style of music serves as a reminder to many Mennonites of their simple lives, as well as their history as a persecuted people. Some branches of Mennonites have retained this "plain" lifestyle into modern times.

Statistics

TheMennonite World Conference

The Mennonite World Conference (MWC) is a Mennonite Anabaptist Christian denomination. Its headquarters are in Kitchener, Ontario, Canada.

History

The first ''Mennonite World Conference'' was held in Basel in 1925. Its main purpose was to celebra ...

was founded at the first conference in Basel

, french: link=no, Bâlois(e), it, Basilese

, neighboring_municipalities= Allschwil (BL), Hégenheim (FR-68), Binningen (BL), Birsfelden (BL), Bottmingen (BL), Huningue (FR-68), Münchenstein (BL), Muttenz (BL), Reinach (BL), Riehen (BS ...

, Switzerland, in 1925 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Anabaptism

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. ...

. In 2022, the organization would have it would have 109 member denominations in 59 countries, and 1.47 million baptized members in 10,300 churches.

Beliefs and practices

The beliefs of the movement are those of theBelievers' Church The believers' Church is a theological doctrine of Evangelical Christianity that teaches that one becomes a member of the Church by new birth and profession of faith. Adherence to this doctrine is a common feature of defining an Evangelical Christia ...

.

One of the earliest expressions of Mennonite Anabaptist faith was the Schleitheim Confession

The Schleitheim Confession was the most representative statement of Anabaptist principles, by a group of Swiss Anabaptists in 1527 in Schleitheim, Switzerland. The real title is ''Brüderliche vereynigung etzlicher Kinder Gottes siben Artickel bet ...

, adopted on February 24, 1527. Its seven articles covered:

* The Ban (excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

)

* Breaking of bread ( Communion)

* Separation from and shunning of the abomination

Abomination may refer to:

* Abomination (Bible), covering Biblical references

**Abomination (Judaism)

*Abomination (character)

The Abomination is a fictional character appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. The original ...

(the Roman Catholic Church and other "worldly" groups and practices)

* Believer's baptism

* Pastor

A pastor (abbreviated as "Pr" or "Ptr" , or "Ps" ) is the leader of a Christian congregation who also gives advice and counsel to people from the community or congregation. In Lutheranism, Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy and ...

s in the church

* Renunciation of the sword (Christian pacifism

Christian pacifism is the theological and ethical position according to which pacifism and non-violence have both a scriptural and rational basis for Christians, and affirms that any form of violence is incompatible with the Christian faith. Chr ...

)

* Renunciation of the oath (swearing as proof of truth)

The Dordrecht Confession of Faith

The Dordrecht Confession of Faith is a statement of religious beliefs adopted by Dutch Mennonite leaders at a meeting in Dordrecht, the Netherlands, on 21 April 1632. Its 18 articles emphasize belief in salvation through Jesus Christ, baptism, ...

was adopted on April 21, 1632, by Dutch Mennonites, by Alsatian Mennonites in 1660, and by North American Mennonites in 1725. It has been followed by many Mennonite groups over the centuries. With regard to salvation

Salvation (from Latin: ''salvatio'', from ''salva'', 'safe, saved') is the state of being saved or protected from harm or a dire situation. In religion and theology, ''salvation'' generally refers to the deliverance of the soul from sin and its c ...

, Mennonites believe:

Traditionally, Mennonites sought to continue the beliefs of early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish ...

and thus practice the lovefeast

An agape feast or lovefeast (also spelled love feast or love-feast, sometimes capitalized) is a communal meal shared among Christians. The name comes from ''agape'', a Greek term for 'love' in its broadest sense.

The lovefeast custom originat ...

(which includes footwashing

Maundy (from Old French ''mandé'', from Latin ''mandatum'' meaning "command"), or Washing of the Saints' Feet, Washing of the Feet, or Pedelavium or Pedilavium, is a religious rite observed by various Christian denominations. The Latin word ...

, the holy kiss

The kiss of peace is an ancient traditional Christian greeting, sometimes also called the "holy kiss", "brother kiss" (among men), or "sister kiss" (among women). Such greetings signify a wish and blessing that peace be with the recipient, and be ...

and communion), headcovering, nonresistance Nonresistance (or non-resistance) is "the practice or principle of not resisting authority, even when it is unjustly exercised". At its core is discouragement of, even opposition to, physical resistance to an enemy. It is considered as a form of pri ...

, the sharing of possessions and nonconformity to the world; these things are heavily emphasized in Old Order Mennonite

Old Order Mennonites (Pennsylvania Dutch language, Pennsylvania German: ) form a branch of the Mennonite tradition. Old Order Movement, Old Order are those Mennonite groups of Swiss people, Swiss German and south Germans, German heritage who pract ...

and Conservative Mennonite

Conservative Mennonites include numerous Conservative Anabaptist groups that identify with the theologically conservative element among Mennonite Anabaptist Christian fellowships, but who are not Old Order groups or mainline denominations.

Con ...

denominations.

Seven ordinances have been taught in many traditional Mennonite churches, which include "baptism, communion, footwashing, marriage, anointing with oil, the holy kiss, and the prayer covering."

In 1911, the Mennonite church in the Netherlands () was the first Dutch church to have a female pastor authorized; she was Anne Zernike.

There is a wide scope of worship, doctrine and traditions among Mennonites today. This section shows the ''main'' types of Mennonites as seen from North America. It is far from a specific study of all Mennonite classifications worldwide but it does show a somewhat representative sample of the complicated classifications within the Mennonite faith worldwide.

Moderate Mennonites include the largest denominations, the Mennonite Brethren

The Mennonite Brethren Church is an evangelical Mennonite Anabaptist movement with congregations.

History

The conference was established among Plautdietsch-speaking Russian Mennonites in 1860. During the 1850s, some Mennonites were influenced b ...

and the Mennonite Church. In most forms of worship and practice, they differ very little from many Protestant congregations. There is no special form of dress and no restrictions on use of technology. Worship styles vary greatly between different congregations. There is no formal liturgy; services typically consist of singing, scripture reading, prayer and a sermon. Some churches prefer hymns and choirs; others make use of contemporary Christian music with electronic instruments. Mennonite congregations are self-supporting and appoint their own ministers. There is no requirement for ministers to be approved by the denomination, and sometimes ministers from other denominations will be appointed. A small sum, based on membership numbers, is paid to the denomination, which is used to support central functions such as publication of newsletters and interactions with other denominations and other countries. The distinguishing characteristics of moderate Mennonite churches tend to be ones of emphasis rather than rule. There is an emphasis on peace, community and service. However, members do not live in a separate community—they participate in the general community as "salt and light" to the world (Matthew 5

Matthew 5 is the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament. It contains the first portion of the Sermon on the Mount, the other portions of which are contained in chapters 6 and 7. Portions are similar to the Sermon on the ...

:13,14). The main elements of Menno Simons' doctrine are retained but in a moderated form. Banning is rarely practiced and would, in any event, have much less effect than in those denominations where the community is more tightly knit. Excommunication can occur and was notably applied by the Mennonite Brethren to members who joined the military during the Second World War. Service in the military is generally not permitted, but service in the legal profession or law enforcement is acceptable. Outreach and help to the wider community at home and abroad is encouraged. The Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) is a leader in foreign aid provision.

Traditionally, very modest dress was expected, particularly in Conservative Mennonite

Conservative Mennonites include numerous Conservative Anabaptist groups that identify with the theologically conservative element among Mennonite Anabaptist Christian fellowships, but who are not Old Order groups or mainline denominations.

Con ...

circles. As the Mennonite population has become urbanized and more integrated into the wider culture, this visible difference has disappeared outside of Conservative Mennonite groups.

The Reformed Mennonite

The Reformed Mennonite Church is an Anabaptist religious denomination that officially separated from the main North American Mennonite body in 1812.

History

The Reformed Mennonite Church was founded on May 30, 1812, in Lancaster County, Pennsyl ...

Church, with members in the United States and Canada, represents the first division in the original North American Mennonite body. Called the "First Keepers of the Old Way" by author Stephen Scott, the Reformed Mennonite Church formed in the very early 19th century. Reformed Mennonites see themselves as true followers of Menno Simons' teachings and of the teachings of the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

. They have no church rules, but they rely solely on the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

as their guide. They insist on strict separation from all other forms of worship and dress in conservative plain garb that preserves 18th century Mennonite details. However, they refrain from forcing their Mennonite faith on their children, allow their children to attend public schools, and have permitted the use of automobiles. They are notable for being the church of Milton S. Hershey

Milton Snavely Hershey (September 13, 1857 – October 13, 1945) was an American chocolatier, businessman, and philanthropist.

Trained in the confectionery business, Hershey pioneered the manufacture of caramel, using fresh milk. He launched t ...

's mother and famous for the long and bitter ban of Robert Bear, a Pennsylvania farmer who rebelled against what he saw as dishonesty and disunity in the leadership.

The Church of God in Christ, Mennonite

The Church of God in Christ, Mennonite, also called Holdeman Mennonite, is a Christian Church of Anabaptist heritage. Its formation started in 1859 under its first leader, a self-described prophet named John Holdeman (1832-1900), who was a ba ...

, a group often called Holdeman Mennonites after their founder John Holdeman, was founded from a schism in 1859. They emphasize Evangelical conversion and strict church discipline. They stay separate from other Mennonite groups because of their emphasis on the one-true-church doctrine and their use of avoidance toward their own excommunicated members. The Holdeman Mennonites do not believe that the use of modern technology is a sin in itself, but they discourage too intensive a use of the Internet and avoid television, cameras and radio. The group had 24,400 baptized members in 2013.

Old Order Mennonites

Old Order Mennonites ( Pennsylvania German: ) form a branch of the Mennonite tradition. Old Order are those Mennonite groups of Swiss German and south German heritage who practice a lifestyle without some elements of modern technology, who still ...

cover several distinct groups. Some groups use horse and buggy for transportation and speak German while others drive cars and speak English. What most Old Orders share in common is conservative doctrine, dress, and traditions, common roots in 19th-century and early 20th-century schisms, and a refusal to participate in politics and other so-called "sins of the world". Most Old Order groups also school their children in Mennonite-operated schools.

* Horse and Buggy Old Order Mennonites came from the main series of Old Order schisms that began in 1872 and ended in 1901 in Ontario, Pennsylvania, and the U.S. Midwest, as conservative Mennonites fought the radical changes that the influence of 19th century American Revivalism had on Mennonite worship. Most Horse and Buggy Old Order Mennonites allow the use of tractors for farming, although some groups insist on steel-wheeled tractors to prevent tractors from being used for road transportation. Like the Stauffer or Pike Mennonites (origin 1845 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania), the Groffdale Conference, and the Old Order Mennonite Conference of Ontario, they stress separation from the world, excommunication, and the wearing of plain clothes. Some Old Order Mennonite groups are unlike the Stauffer or Pike Mennonites in that their form of the ban is less severe because the ex-communicant is not shunned, and is therefore not excluded from the family table, shunned by their spouse, or cut off from business dealings.

* Automobile Old Order Mennonites

Old Order Mennonites ( Pennsylvania German: ) form a branch of the Mennonite tradition. Old Order are those Mennonite groups of Swiss German and south German heritage who practice a lifestyle without some elements of modern technology, who still ...

, also known as Weaverland Conference Mennonites (having their origins in the Weaverland District of the Lancaster Conference—also calling "Horning"), or Wisler Mennonites in the U.S. Midwest, or the Markham-Waterloo Mennonite Conference

The Markham-Waterloo Mennonite Conference (MWMC) is a Canadian, progressive Old Order Mennonite church established in 1939 in Ontario, Canada. It has its roots in the Old Order Mennonite Conference in Markham, Ontario, and in what is now called th ...

having its origins from the Old Order Mennonites of Ontario, Canada, also evolved from the main series of Old Order schisms from 1872 to 1901. They often share the same meeting houses with, and adhere to almost identical forms of Old Order worship as their Horse and Buggy Old Order brethren with whom they parted ways in the early 20th century. Although this group began using cars in 1927, the cars were required to be plain and painted black. The largest group of Automobile Old Orders are still known today as "Black Bumper" Mennonites because some members still paint their chrome bumpers black.

Stauffer Mennonite The Stauffer Mennonites, or "Pikers", are a group of Old Order Mennonites. They are also called "Team Mennonites", because they use horse drawn transportation. In 2015 the Stauffer Mennonites had 1,792 adult members.

History

The original Church ...

s, or Pike Mennonites, represent one of the first and most conservative forms of North American Horse and Buggy Mennonites. They were founded in 1845, following conflicts about how to discipline children and spousal abuse

Domestic violence (also known as domestic abuse or family violence) is violence or other abuse that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage or cohabitation. ''Domestic violence'' is often used as a synonym for ''intimate partner ...

by a few Mennonite Church members. They almost immediately began to split into separate churches themselves. Today these groups are among the most conservative of all Swiss Mennonites outside the Amish. They stress strict separation from "the world", adhere to "strict withdrawal from and shunning of apostate and separated members", forbid and limit cars and technology and wear plain clothing.

Conservative Mennonites

Conservative Mennonites include numerous Conservative Anabaptist groups that identify with the theologically conservative element among Mennonite Anabaptist Christian fellowships, but who are not Old Order groups or mainline denominations.

Con ...

are generally considered those Mennonites who maintain somewhat conservative dress, although carefully accepting other technology. They are not a unified group and are divided into various independent conferences and fellowships such as the Eastern Pennsylvania Mennonite Church Conference. Despite the rapid changes that precipitated the Old Order schisms in the last quarter of the 19th century, most Mennonites in the United States and Canada retained a core of traditional beliefs based on a literal interpretation of the New Testament scriptures as well as more external "plain" practices into the beginning of the 20th century. However, disagreements in the United States and Canada between conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

and progressive (i.e. less emphasis on literal interpretation of scriptures) leaders began in the first half of the 20th century and continue to some extent today. Following WWII, a conservative movement emerged from scattered separatist groups as a reaction to the Mennonite churches drifting away from their historical traditions. "Plain" became passé as open criticisms of traditional beliefs and practices broke out in the 1950s and 1960s. The first conservative withdrawals from the progressive group began in the 1950s. These withdrawals continue to the present day in what is now the growing Conservative Movement formed from Mennonite schisms and from combinations with progressive Amish groups. While moderate and progressive Mennonite congregations have dwindled in size, the Conservative Movement congregations continue to exhibit considerable growth. Other conservative Mennonite groups descended from the former Amish-Mennonite churches which split, like the Wisler Mennonites, from the Old Order Amish in the latter part of the 19th century. (The Wisler Mennonites are a grouping descended from the Old Mennonite Church.) There are also other Conservative Mennonite churches that descended from more recent groups that have left the Amish like the Beachy Amish

The Beachy Amish Mennonites, also known as the Beachy Mennonites, are an Anabaptist group of churches in the Conservative Mennonite tradition that have Amish roots. Although they have retained the name "Amish" they are quite different from the O ...

or the Tennessee Brotherhood Churches.

In North America, there are structures and traditions taught as in the Confession of Faith in a Mennonite Perspective of Mennonite Church Canada and Mennonite Church USA.

Progressive Mennonite churches allow LGBTQ+

' is an initialism that stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender. In use since the 1990s, the initialism, as well as some of its common variants, functions as an umbrella term for sexuality and gender identity.

The LGBT term is ...

members to worship as church members and have been banned from membership, in some cases in the moderate groups as a result. The Germantown Mennonite Church in Germantown, Pennsylvania is one example of such a progressive Mennonite church.

Some progressive Mennonite Churches place a great emphasis on the Mennonite tradition's teachings on pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

and non-violence

Nonviolence is the personal practice of not causing harm to others under any condition. It may come from the belief that hurting people, animals and/or the environment is unnecessary to achieve an outcome and it may refer to a general philosoph ...

. Some progressive Mennonite Churches are part of moderate Mennonite denominations (such as the Mennonite Church USA) while others are independent congregations.

Sexuality, marriage, and family mores

Most Mennonite denominations hold a conservative position on homosexuality. The Brethren Mennonite Council for LGBT Interests was founded in 1976 in the USA and has member churches of different denominations in the USA and Canada. TheMennonite Church Canada

Mennonite Church Canada is a Mennonite denomination in Canada, with head offices in Winnipeg, Manitoba. It is a member of the Mennonite World Conference and the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada.

History

The first Mennonites in Canada arrived from ...

leaves the choice to each church for same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same Legal sex and gender, sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being ...

.

The Mennonite Church in the Netherlands

The Mennonite Church in the Netherlands, or ''Algemene Doopsgezinde Sociëteit'', is a body of Mennonite Christians in the Netherlands.

The Mennonites (or Mennisten or Doopsgezinden) are named for Menno Simons (1496–1561), a Dutch Roman Catholi ...

and the Mennonite Church USA

The Mennonite Church USA (MC USA) is an Anabaptist Christian denomination in the United States. Although the organization is a recent 2002 merger of the Mennonite Church and the General Conference Mennonite Church, the body has roots in the Radi ...

permit same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same Legal sex and gender, sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being ...

.

Russian Mennonites

The "Russian Mennonites" (German: "Russlandmennoniten") today are descended from DutchAnabaptists

Anabaptism (from New Latin language, Neo-Latin , from the Greek language, Greek : 're-' and 'baptism', german: Täufer, earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re- ...

, who came from the Netherlands and started around 1530 to settle around Danzig and in West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

, where they lived for about 250 years. During that time they mixed with German Mennonites from different regions. Starting in 1791 they established colonies in the south-west of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

(present-day Ukraine) and beginning in 1854 also in Volga region

The Volga Region (russian: Поволжье, ''Povolzhye'', literally: "along the Volga") is a historical region in Russia that encompasses the drainage basin of the Volga River, the longest river in Europe, in central and southern European Russ ...

and Orenburg Governorate

Orenburg Governorate (russian: Оренбургская губерния) was an administrative division (a '' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire with the center in the city of Orenburg, Ufa (1802-1865).

The governorate was created in 1744 from ...

(present-day Russia). Their ethno-language is Plautdietsch, a Germanic dialect of the East Low German

East Low German (german: ostniederdeutsche Dialekte, ostniederdeutsche Mundarten, Ostniederdeutsch; nds, Oostplattdütsch) is a group of Low German dialects spoken in north-eastern Germany as well as by minorities in northern Poland. Together ...

group, with some Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

admixture. Today, many traditional Russian Mennonites use Standard German

Standard High German (SHG), less precisely Standard German or High German (not to be confused with High German dialects, more precisely Upper German dialects) (german: Standardhochdeutsch, , or, in Switzerland, ), is the standardized variety ...

in church and for reading and writing.

In the 1770s Catherine the Great

, en, Catherine Alexeievna Romanova, link=yes

, house =

, father = Christian August, Prince of Anhalt-Zerbst

, mother = Joanna Elisabeth of Holstein-Gottorp

, birth_date =

, birth_name = Princess Sophie of Anhal ...

of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

acquired a great deal of land north of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

(in present-day Ukraine) following the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histo ...

and the takeover of the Ottoman vassal, the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to ...

. Russian government officials invited Mennonites living in the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

to farm the Ukrainian steppes depopulated by Tatar raids in exchange for religious freedom and military exemption. Over the years Mennonite farmers and businesses were very successful.

In 1854, according to the new Russian government official invitation, Mennonites from Prussia established colonies in Russia's Volga region

The Volga Region (russian: Поволжье, ''Povolzhye'', literally: "along the Volga") is a historical region in Russia that encompasses the drainage basin of the Volga River, the longest river in Europe, in central and southern European Russ ...

, and later in Orenburg Governorate

Orenburg Governorate (russian: Оренбургская губерния) was an administrative division (a '' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire with the center in the city of Orenburg, Ufa (1802-1865).

The governorate was created in 1744 from ...

(Neu Samara Colony

Neu Samara was a colony of Plautdietsch-speaking Mennonites in the Orenburg region of Russia.

Founding

Neu Samara was formed by Mennonite settlers of Plautdietsch language, culture and ancestry in 1891-92 who came from the Molotschna mother col ...

).

Between 1874 and 1880 some 16,000 Mennonites of approximately 45,000 left Russia. About nine thousand departed for the United States (mainly Kansas and Nebraska) and seven thousand for Canada (mainly Manitoba). In the 1920s, Russian Mennonites from Canada started to migrate to Latin America (Mexico and Paraguay), soon followed by Mennonite refugees from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

. Further migrations of these Mennonites led to settlements in Peru, Brazil, Uruguay, Belize, Bolivia and Argentina.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the Mennonites in Russia owned large agricultural estates and some had become successful as industrial entrepreneurs in the cities, employing wage labor. After the Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

and the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

(1917–1921), all of these farms (whose owners were called Kulak

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ove ...

s) and enterprises were expropriated by local peasants or the Soviet government. Beyond expropriation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

, Mennonites suffered severe persecution during the course of the Civil War, at the hands of workers, the Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and, particularly, the Anarcho-Communists

Anarcho-communism, also known as anarchist communism, (or, colloquially, ''ancom'' or ''ancomm'') is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retains res ...

of Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, The surname "Makhno" ( uk, Махно́) was itself a corruption of Nestor's father's surname "Mikhnenko" ( uk, Міхненко). ( 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ("Father Makhno"),; According to ...

, who considered the Mennonites to be privileged foreigners of the upper class and targeted them. During expropriation, hundreds of Mennonite men, women and children were murdered in these attacks. After the Ukrainian–Soviet War

The Ukrainian–Soviet War ( uk, радянсько-українська війна, translit=radiansko-ukrainska viina) was an armed conflict from 1917 to 1921 between the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Bolsheviks (Soviet Ukraine and So ...

and the takeover of Ukraine by the Soviet Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

, people who openly practiced religion were in many cases imprisoned by the Soviet government. This led to a wave of Mennonite emigration to the Americas (U.S., Canada and Paraguay).

When the German army invaded the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941 during World War II, many in the Mennonite community perceived them as liberators from the communist regime under which they had suffered. Many Russian Mennonites actively collaborated with the Nazis, including in the rounding up and extermination of their Jewish neighbors, although some also resisted them. When the tide of war turned, many of the Mennonites fled with the German army back to Germany where they were accepted as ''Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of '' volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

''. The Soviet government believed that the Mennonites had "collectively collaborated" with the Germans. After the war, many Mennonites in the Soviet Union were forcibly relocated to Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

and Kazakhstan. Many were sent to gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

s as part of the Soviet program of mass internal deportations of various ethnic groups whose loyalty was seen as questionable. Many German-Russian Mennonites who lived to the east (not in Ukraine) were deported to Siberia before the German army's invasion and were also often placed in labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

s. In the decades that followed, as the Soviet regime became less brutal, a number of Mennonites returned to Ukraine and Western Russia where they had formerly lived. In the 1990s the governments of Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine gave these people the opportunity to emigrate, and the vast majority emigrated to Germany. The Russian Mennonite immigrants in Germany from the 1990s outnumber the pre-1989 community of Mennonites by three to one.

By 2015, the majority of Russian Mennonites and their descendants live in Latin America, Germany and Canada.

The world's most conservative Mennonites (in terms of culture and technology) are the Mennonites affiliated with the Lower and Upper Barton Creek Colonies in Belize. Lower Barton is inhabited by Plautdietsch speaking Russian Mennonites, whereas Upper Barton Creek is mainly inhabited by Pennsylvania Dutch language

Pennsylvania Dutch (, or ), referred to as Pennsylvania German in scholarly literature, is a variety (linguistics), variety of Palatine German language, Palatine German, also known as Palatine Dutch, spoken by the Amish, Old Order Amish, Old Or ...

-speaking Mennonites from North America. Neither group uses motors or paint.

North America

Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

Evangelists moved into Germany they received a sympathetic audience among the larger of these German-Mennonite congregations around Krefeld

Krefeld ( , ; li, Krieëvel ), also spelled Crefeld until 1925 (though the spelling was still being used in British papers throughout the Second World War), is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located northwest of Düsseldorf, i ...

, Altona, Hamburg

Altona (), also called Hamburg-Altona, is the westernmost urban borough (''Bezirk'') of the German city state of Hamburg, on the right bank of the Elbe river. From 1640 to 1864, Altona was under the administration of the Danish monarchy. Alto ...

, Gronau and Emden

Emden () is an independent city and seaport in Lower Saxony in the northwest of Germany, on the river Ems. It is the main city of the region of East Frisia and, in 2011, had a total population of 51,528.

History

The exact founding date of E ...

. It was among this group of Quakers and Mennonites, living under ongoing discrimination, that William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

solicited settlers for his new colony. The first permanent settlement of Mennonites in the American colonies consisted of one Mennonite family and twelve Mennonite-Quaker families of German extraction who arrived from Krefeld

Krefeld ( , ; li, Krieëvel ), also spelled Crefeld until 1925 (though the spelling was still being used in British papers throughout the Second World War), is a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is located northwest of Düsseldorf, i ...

, Germany, in 1683 and settled in Germantown, Pennsylvania. Among these early settlers was William Rittenhouse

William Rittenhouse (1644 – 1708) was an American papermaker and businessman. He served as an apprentice papermaker in the Netherlands and, after moving to the Pennsylvania Colony, established the first paper mill in the North American colon ...

, a lay minister and owner of the first American paper mill. Jacob Gottschalk

Jacob Gottschalk (Godtschalk) Henricks van der Heggen (c.1670 – c.1763) was the first person to serve as a Mennonite bishop in America.

Life

Gottschalk was born around 1670 in Germany, in Goch, a town at the Dutch border. In 1701, he receiv ...

was the first bishop of this Germantown congregation. This early group of Mennonites and Mennonite-Quakers wrote the first formal protest against slavery in the United States. The treatise was addressed to slave-holding Quakers in an effort to persuade them to change their ways.

In the early 18th century, 100,000 Germans from the Palatinate emigrated to Pennsylvania, where they became known collectively as the Pennsylvania Dutch (from the Anglicization of ''Deutsch

Deutsch or Deutsche may refer to:

*''Deutsch'' or ''(das) Deutsche'': the German language, in Germany and other places

*''Deutsche'': Germans, as a weak masculine, feminine or plural demonym

*Deutsch (word), originally referring to the Germanic ve ...

'' or German.) The Palatinate region had been repeatedly overrun by the French in religious wars, and Queen Anne had invited the Germans to go to the British colonies. Of these immigrants, around 2,500 were Mennonites and 500 were Amish. This group settled farther west than the first group, choosing less expensive land in the Lancaster area. The oldest Mennonite meetinghouse in the United States is the Hans Herr House

The Hans Herr House, also known as the Christian Herr House, is a historic home located in West Lampeter Township, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It was built in 1719, and is a -story, rectangular sandstone Germanic dwelling. It measures 37 ...

in West Lampeter Township

West Lampeter Township is a township in central Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, United States. The population was 17,365 at the 2020 census.

History

The Johannes Harnish Farmstead, Christian and Emma Herr Farm, Hans Herr House, Lime Valley Cov ...

. ''Note:'' This includes A member of this second group, Christopher Dock