Mendelian ratio on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological

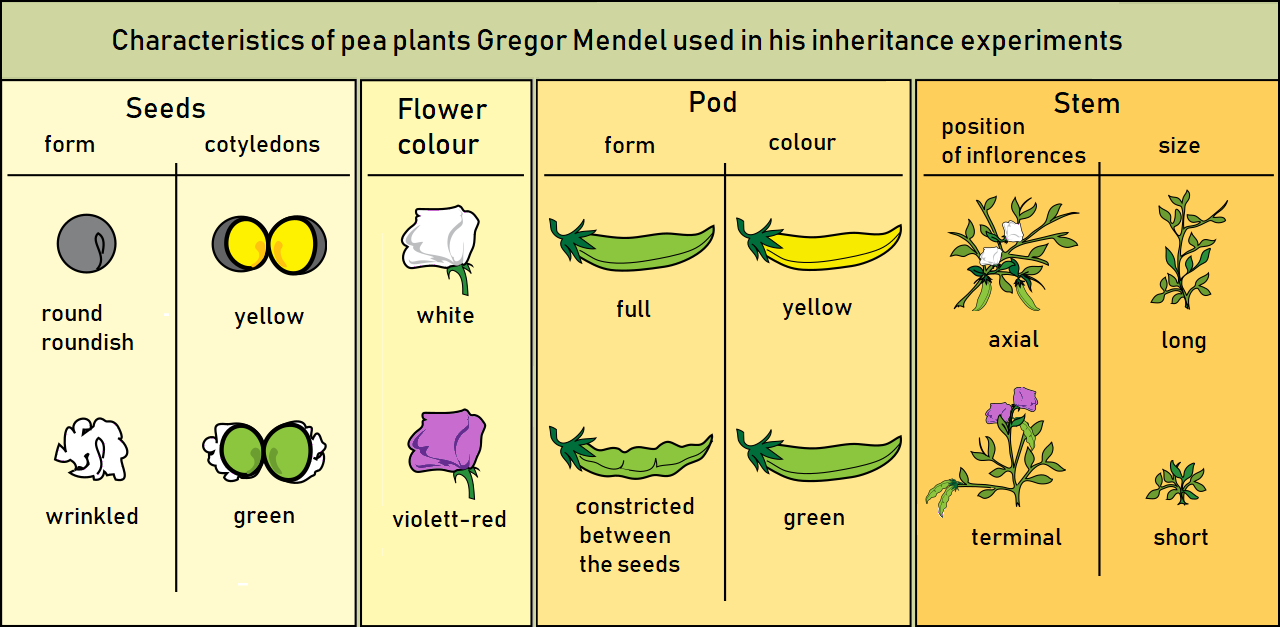

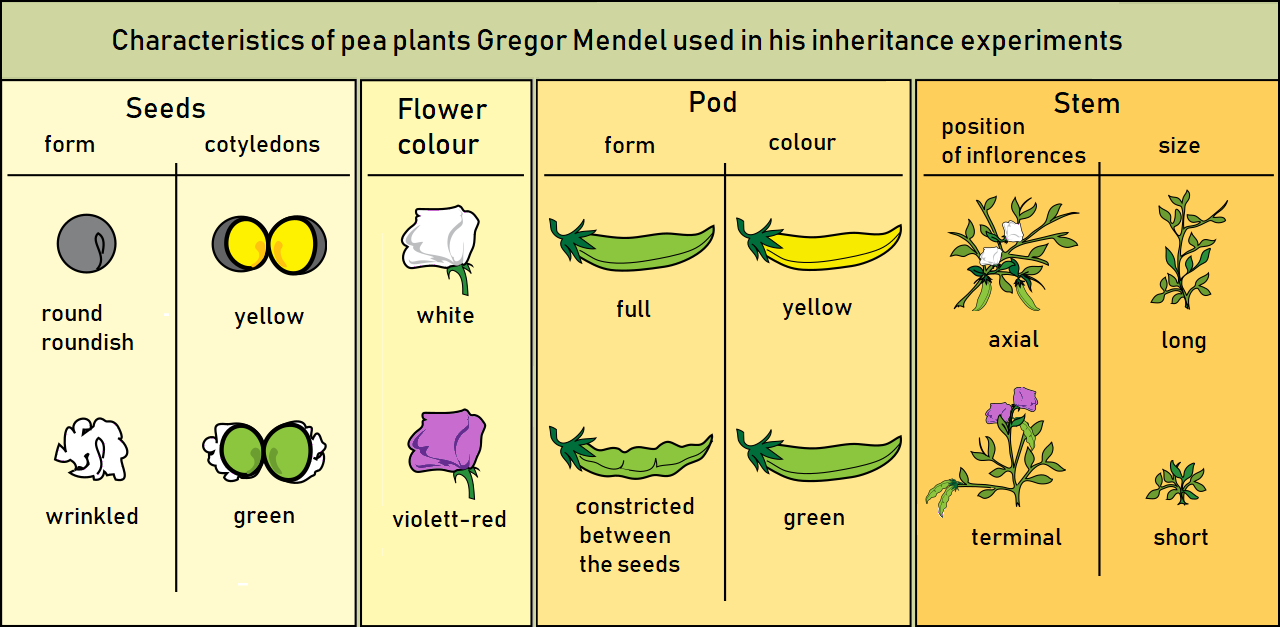

Mendel selected for the experiment the following characters of pea plants:

* Form of the ripe seeds (round or roundish, surface shallow or wrinkled)

* Colour of the seed–coat (white, gray, or brown, with or without violet spotting)

* Colour of the

Mendel selected for the experiment the following characters of pea plants:

* Form of the ripe seeds (round or roundish, surface shallow or wrinkled)

* Colour of the seed–coat (white, gray, or brown, with or without violet spotting)

* Colour of the

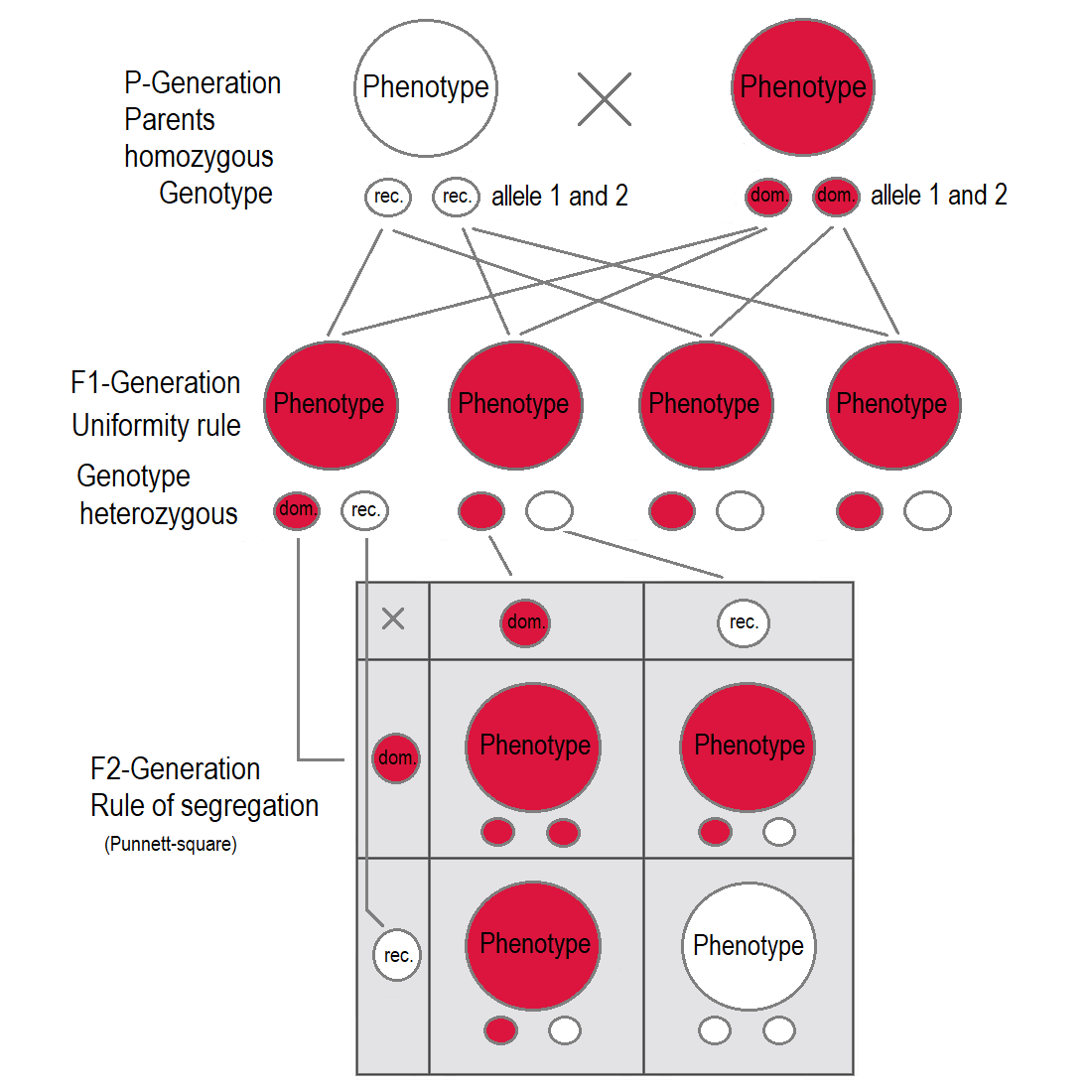

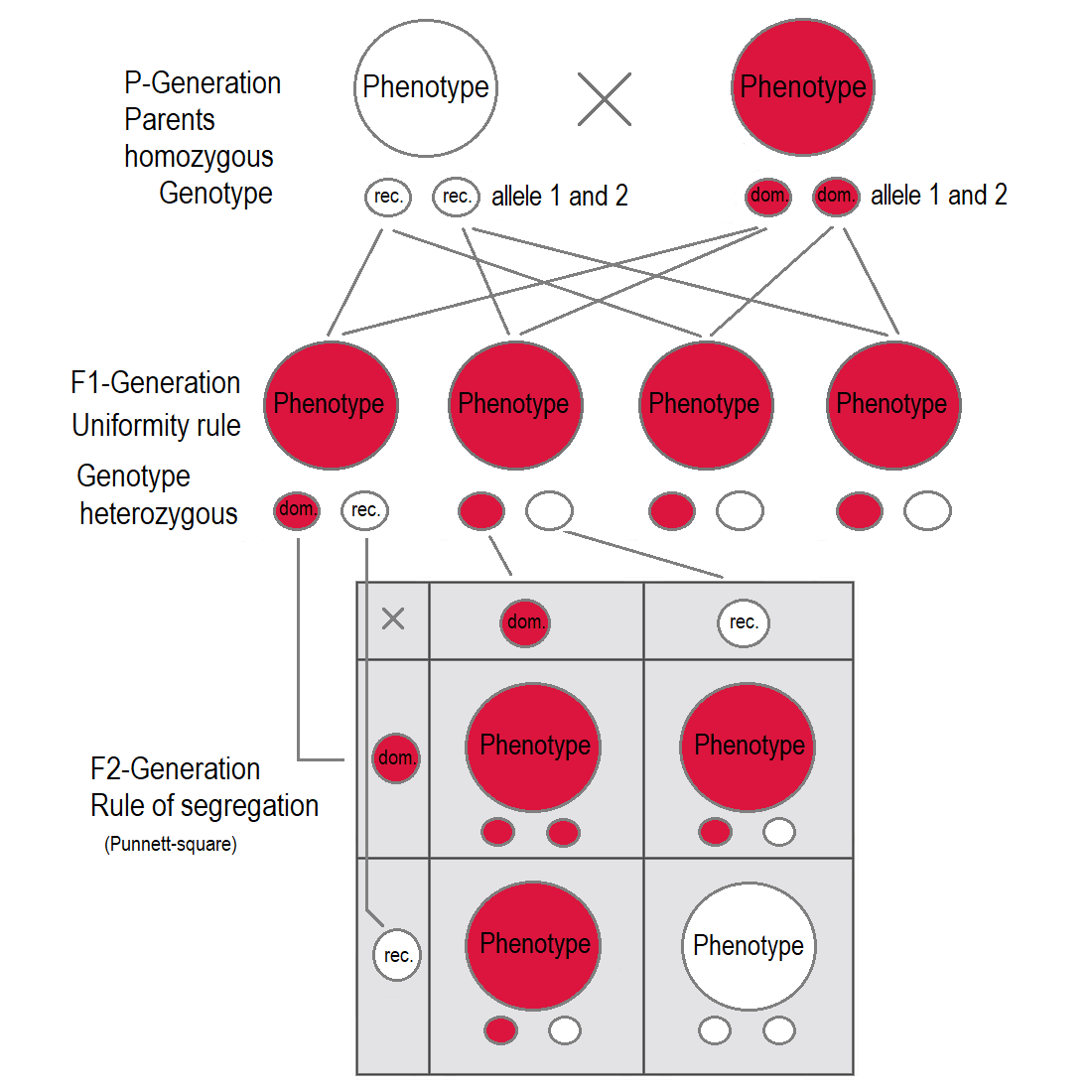

If two parents are mated with each other who differ in one genetic characteristic for which they are both

If two parents are mated with each other who differ in one genetic characteristic for which they are both

The Law of Segregation of genes applies when two individuals, both heterozygous for a certain trait are crossed, for example hybrids of the F1-generation. The offspring in the F2-generation differ in genotype and phenotype, so that the characteristics of the grandparents (P-generation) regularly occur again. In a dominant-recessive inheritance an average of 25% are homozygous with the dominant trait, 50% are heterozygous showing the dominant trait in the phenotype (

The Law of Segregation of genes applies when two individuals, both heterozygous for a certain trait are crossed, for example hybrids of the F1-generation. The offspring in the F2-generation differ in genotype and phenotype, so that the characteristics of the grandparents (P-generation) regularly occur again. In a dominant-recessive inheritance an average of 25% are homozygous with the dominant trait, 50% are heterozygous showing the dominant trait in the phenotype (

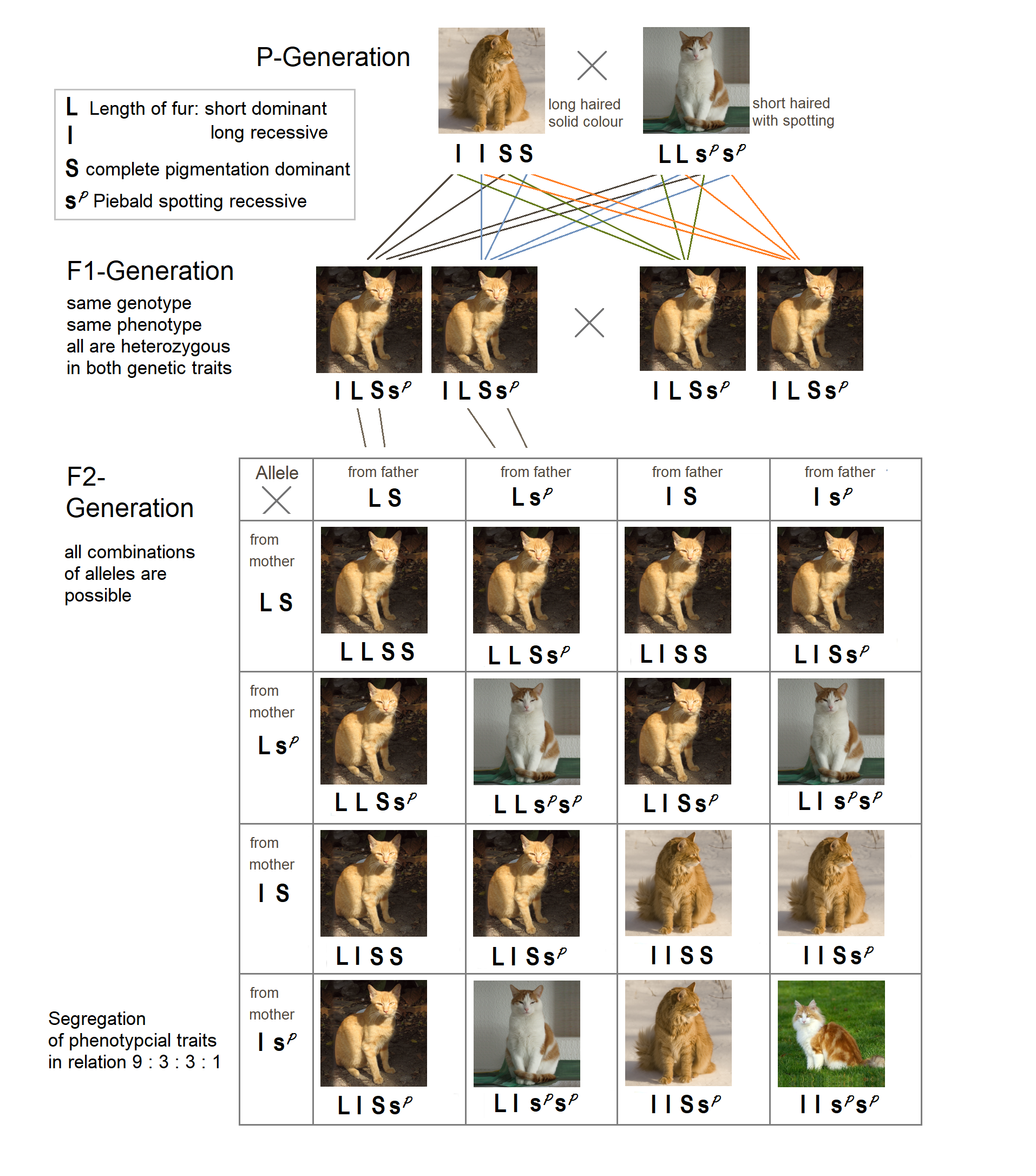

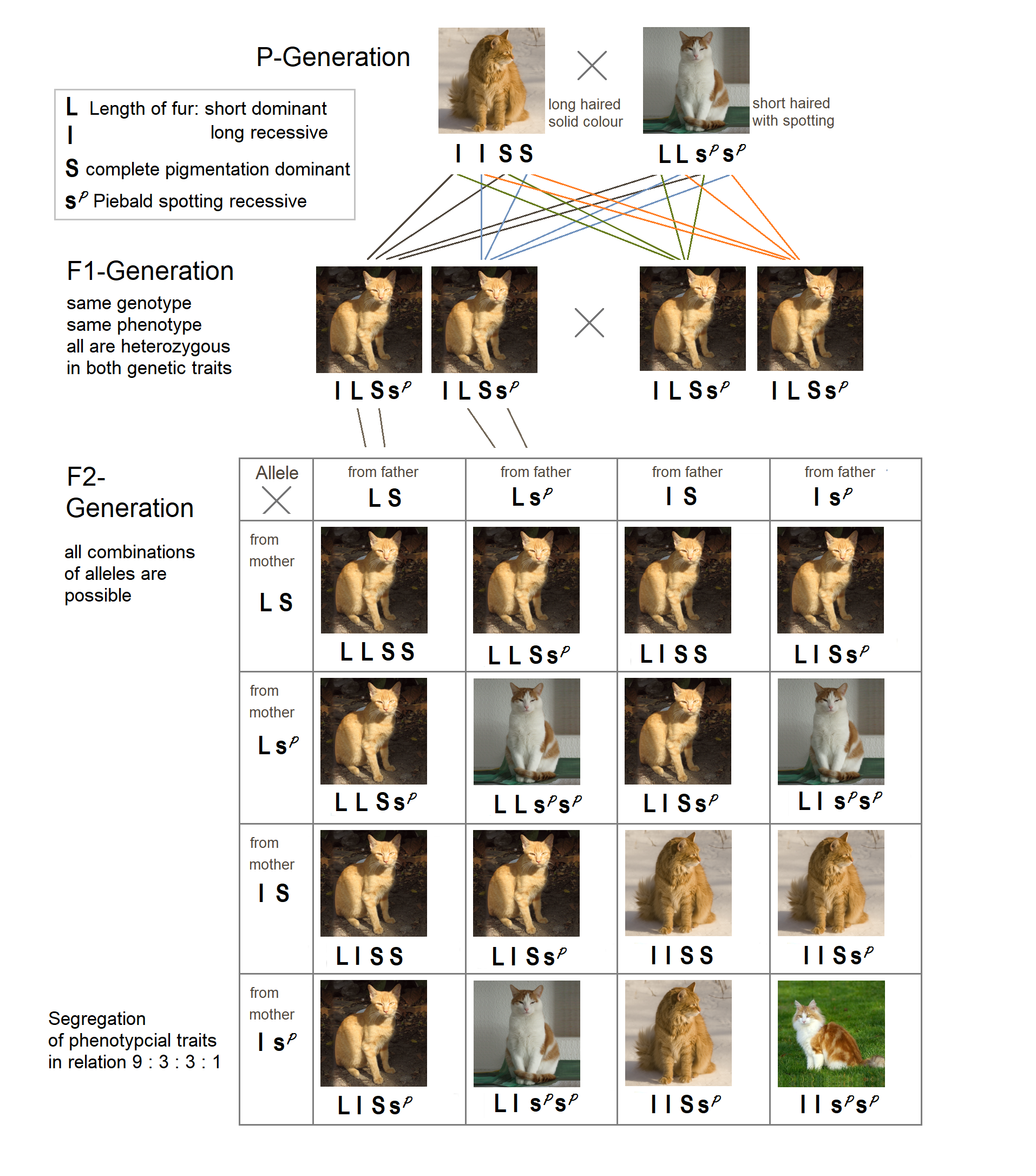

The Law of Independent Assortment states that alleles for separate traits are passed independently of one another. That is, the biological selection of an allele for one trait has nothing to do with the selection of an allele for any other trait. Mendel found support for this law in his dihybrid cross experiments. In his monohybrid crosses, an idealized 3:1 ratio between dominant and recessive phenotypes resulted. In dihybrid crosses, however, he found a 9:3:3:1 ratios. This shows that each of the two alleles is inherited independently from the other, with a 3:1 phenotypic ratio for each.

Independent assortment occurs in

The Law of Independent Assortment states that alleles for separate traits are passed independently of one another. That is, the biological selection of an allele for one trait has nothing to do with the selection of an allele for any other trait. Mendel found support for this law in his dihybrid cross experiments. In his monohybrid crosses, an idealized 3:1 ratio between dominant and recessive phenotypes resulted. In dihybrid crosses, however, he found a 9:3:3:1 ratios. This shows that each of the two alleles is inherited independently from the other, with a 3:1 phenotypic ratio for each.

Independent assortment occurs in

Variations on Mendel's laws (overview)

/ref> For example, Mendel focused on traits whose genes have only two alleles, such as "A" and "a". However, many genes have more than two alleles. He also focused on traits determined by a single gene. But some traits, such as height, depend on many genes rather than just one. Traits dependent on multiple genes are called

Khan Academy, video lecture

Mendel's principles of Inheritance

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mendelian Inheritance Classical genetics

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, Title (property), titles, debts, entitlements, Privilege (law), privileges, rights, and Law of obligations, obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ ...

following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, Augustinians, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thomas' Abbey in Br� ...

in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries () (16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware o ...

and Carl Correns

Carl Erich Correns (19 September 1864 – 14 February 1933) was a German botanist and geneticist notable primarily for his independent discovery of the principles of heredity, which he achieved simultaneously but independently of the botanist ...

, and later popularized by William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscove ...

. These principles were initially controversial. When Mendel's theories were integrated with the Boveri–Sutton chromosome theory

The Boveri–Sutton chromosome theory (also known as the chromosome theory of inheritance or the Sutton–Boveri theory) is a fundamental unifying theory of genetics which identifies chromosomes as the carriers of genetic material.< ...

of inheritance by Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role tha ...

in 1915, they became the core of classical genetics

Classical genetics is the branch of genetics based solely on visible results of reproductive acts. It is the oldest discipline in the field of genetics, going back to the experiments on Mendelian inheritance by Gregor Mendel who made it possible t ...

. Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who a ...

combined these ideas with the theory of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

in his 1930 book ''The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection

''The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection'' is a book by Ronald Fisher which combines Mendelian genetics with Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection, with Fisher being the first to argue that "Mendelism therefore validates Darwinism" and ...

'', putting evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

onto a mathematical

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

footing and forming the basis for population genetics

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and between populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as adaptation, speciation, and pop ...

within the modern evolutionary synthesis.

History

The principles of Mendelian inheritance were named for and first derived byGregor Johann Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinian friar and abbot of St. Thomas' Abbey in Brünn (''Brno''), Margraviate of Moravia. Mendel was ...

, a nineteenth-century Moravian monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

who formulated his ideas after conducting simple hybridisation experiments with pea plants (''Pisum sativum

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

'') he had planted in the garden of his monastery. Between 1856 and 1863, Mendel cultivated and tested some 5,000 pea plants. From these experiments, he induced two generalizations which later became known as ''Mendel's Principles of Heredity'' or ''Mendelian inheritance''. He described his experiments in a two-part paper, ''Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden'' (''Experiments on Plant Hybridization

"Experiments on Plant Hybridization" (German: "Versuche über Pflanzen-Hybriden") is a seminal paper written in 1865 and published in 1866 by Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian friar considered to be the founder of modern genetics. The paper was the r ...

''), that he presented to the Natural History Society of Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

on 8 February and 8 March 1865, and which was published in 1866.

Mendel's results were at first largely ignored. Although they were not completely unknown to biologists of the time, they were not seen as generally applicable, even by Mendel himself, who thought they only applied to certain categories of species or traits. A major roadblock to understanding their significance was the importance attached by 19th-century biologists to the apparent blending of many inherited traits in the overall appearance of the progeny, now known to be due to multi-gene interactions, in contrast to the organ-specific binary characters studied by Mendel. In 1900, however, his work was "re-discovered" by three European scientists, Hugo de Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries () (16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware o ...

, Carl Correns

Carl Erich Correns (19 September 1864 – 14 February 1933) was a German botanist and geneticist notable primarily for his independent discovery of the principles of heredity, which he achieved simultaneously but independently of the botanist ...

, and Erich von Tschermak Erich Tschermak, Edler von Seysenegg (15 November 1871 – 11 October 1962) was an Austrian agronomist who developed several new disease-resistant crops, including wheat-rye and oat hybrids. He was a son of the Moravia-born mineralogist Gustav ...

. The exact nature of the "re-discovery" has been debated: De Vries published first on the subject, mentioning Mendel in a footnote, while Correns pointed out Mendel's priority after having read De Vries' paper and realizing that he himself did not have priority. De Vries may not have acknowledged truthfully how much of his knowledge of the laws came from his own work and how much came only after reading Mendel's paper. Later scholars have accused Von Tschermak of not truly understanding the results at all.

Regardless, the "re-discovery" made Mendelism an important but controversial theory. Its most vigorous promoter in Europe was William Bateson

William Bateson (8 August 1861 – 8 February 1926) was an English biologist who was the first person to use the term genetics to describe the study of heredity, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscove ...

, who coined the terms "genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

" and "allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

" to describe many of its tenets. The model of heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

was contested by other biologists because it implied that heredity was discontinuous, in opposition to the apparently continuous variation observable for many traits. Many biologists also dismissed the theory because they were not sure it would apply to all species. However, later work by biologists and statisticians such as Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who a ...

showed that if multiple Mendelian factors were involved in the expression of an individual trait, they could produce the diverse results observed, thus demonstrating that Mendelian genetics is compatible with natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

. Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role tha ...

and his assistants later integrated Mendel's theoretical model with the chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

theory of inheritance, in which the chromosomes of cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery ...

s were thought to hold the actual hereditary material, and created what is now known as classical genetics

Classical genetics is the branch of genetics based solely on visible results of reproductive acts. It is the oldest discipline in the field of genetics, going back to the experiments on Mendelian inheritance by Gregor Mendel who made it possible t ...

, a highly successful foundation which eventually cemented Mendel's place in history.

Mendel's findings allowed scientists such as Fisher and J.B.S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (; 5 November 18921 December 1964), nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biolog ...

to predict the expression of traits on the basis of mathematical probabilities. An important aspect of Mendel's success can be traced to his decision to start his crosses only with plants he demonstrated were true-breeding. He only measured discrete (binary) characteristics, such as color, shape, and position of the seeds, rather than quantitatively variable characteristics. He expressed his results numerically and subjected them to statistical analysis. His method of data analysis and his large sample size

Sample size determination is the act of choosing the number of observations or Replication (statistics), replicates to include in a statistical sample. The sample size is an important feature of any empirical study in which the goal is to make stat ...

gave credibility to his data. He had the foresight to follow several successive generations (P, F1, F2, F3) of pea plants and record their variations. Finally, he performed "test crosses" ( backcrossing descendants of the initial hybridization to the initial true-breeding lines) to reveal the presence and proportions of recessive

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and t ...

characters.

Mendel's genetic discoveries

Five parts of Mendel's discoveries were an important divergence from the common theories at the time and were the prerequisite for the establishment of his rules. # Characters are unitary, that is, they are discrete e.g.: purple ''vs''. white, tall ''vs''. dwarf. There is no medium-sized plant or light purple flower. # Genetic characteristics have alternate forms, each inherited from one of two parents. Today these are calledallele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

s.

# One allele is dominant over the other. The phenotype reflects the dominant allele.

# Gametes are created by random segregation. Heterozygotic individuals produce gametes with an equal frequency of the two alleles.

# Different traits have independent assortment. In modern terms, genes are unlinked.

According to customary terminology, the principles of inheritance discovered by Gregor Mendel are here referred to as Mendelian laws, although today's geneticists also speak of ''Mendelian rules'' or ''Mendelian principles'', as there are many exceptions summarized under the collective term Non-Mendelian inheritance

Non-Mendelian inheritance is any pattern in which traits do not segregate in accordance with Mendel's laws. These laws describe the inheritance of traits linked to single genes on chromosomes in the nucleus. In Mendelian inheritance, each paren ...

.

Mendel selected for the experiment the following characters of pea plants:

* Form of the ripe seeds (round or roundish, surface shallow or wrinkled)

* Colour of the seed–coat (white, gray, or brown, with or without violet spotting)

* Colour of the

Mendel selected for the experiment the following characters of pea plants:

* Form of the ripe seeds (round or roundish, surface shallow or wrinkled)

* Colour of the seed–coat (white, gray, or brown, with or without violet spotting)

* Colour of the seed

A seed is an embryonic plant enclosed in a protective outer covering, along with a food reserve. The formation of the seed is a part of the process of reproduction in seed plants, the spermatophytes, including the gymnosperm and angiospe ...

s and cotyledon

A cotyledon (; ; ; , gen. (), ) is a significant part of the embryo within the seed of a plant, and is defined as "the embryonic leaf in seed-bearing plants, one or more of which are the first to appear from a germinating seed." The numb ...

s (yellow or green)

* Flower colour (white or violet-red)

* Form of the ripe pods (simply inflated, not contracted, or constricted between the seeds and wrinkled)

* Colour of the unripe pods (yellow or green)

* Position of the flowers (axial or terminal)

* Length of the stem

When he crossed purebred white flower and purple flower pea plants (the parental or P generation) by artificial

Artificiality (the state of being artificial or manmade) is the state of being the product of intentional human manufacture, rather than occurring naturally through processes not involving or requiring human activity.

Connotations

Artificiality ...

pollination, the resulting flower colour was not a blend. Rather than being a mix of the two, the offspring in the first generation ( F1-generation) were all purple-flowered. Therefore, he called this biological trait

A phenotypic trait, simply trait, or character state is a distinct variant of a phenotypic characteristic of an organism; it may be either inherited or determined environmentally, but typically occurs as a combination of the two.Lawrence, Eleano ...

dominant. When he allowed self-fertilization

Autogamy, or self-fertilization, refers to the fusion of two gametes that come from one individual. Autogamy is predominantly observed in the form of self-pollination, a reproductive mechanism employed by many flowering plants. However, species o ...

in the uniform looking F1-generation, he obtained both colours in the F2 generation with a purple flower to white flower ratio of 3 : 1. In some of the other characters also one of the traits was dominant.

He then conceived the idea of heredity units, which he called hereditary "factors". Mendel found that there are alternative forms of factors—now called gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s—that account for variations in inherited characteristics. For example, the gene for flower color in pea plants exists in two forms, one for purple and the other for white. The alternative "forms" are now called allele

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

s. For each trait, an organism inherits two alleles, one from each parent. These alleles may be the same or different. An organism that has two identical alleles for a gene is said to be homozygous

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

for that gene (and is called a homozygote). An organism that has two different alleles for a gene is said be heterozygous

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

for that gene (and is called a heterozygote).

Mendel hypothesized that allele pairs separate randomly, or segregate, from each other during the production of the gametes

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce ...

in the seed plant (egg cell

The egg cell, or ovum (plural ova), is the female reproductive cell, or gamete, in most anisogamous organisms (organisms that reproduce sexually with a larger, female gamete and a smaller, male one). The term is used when the female gamete is ...

) and the pollen plant (sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, whi ...

). Because allele pairs separate during gamete production, a sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, whi ...

or egg

An egg is an organic vessel grown by an animal to carry a possibly fertilized egg cell (a zygote) and to incubate from it an embryo within the egg until the embryo has become an animal fetus that can survive on its own, at which point the a ...

carries only one allele for each inherited trait. When sperm and egg unite at fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Proce ...

, each contributes its allele, restoring the paired condition in the offspring. Mendel also found that each pair of alleles segregates independently of the other pairs of alleles during gamete formation.

The genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

of an individual is made up of the many alleles it possesses. The phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

is the result of the expression

Expression may refer to:

Linguistics

* Expression (linguistics), a word, phrase, or sentence

* Fixed expression, a form of words with a specific meaning

* Idiom, a type of fixed expression

* Metaphorical expression, a particular word, phrase, o ...

of all characteristics that are genetically determined by its alleles as well as by its environment. The presence of an allele does not mean that the trait will be expressed in the individual that possesses it. If the two alleles of an inherited pair differ (the heterozygous condition), then one determines the organism's appearance and is called the dominant allele

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and t ...

; the other has no noticeable effect on the organism's appearance and is called the recessive allele

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and t ...

.

Law of Dominance and Uniformity

If two parents are mated with each other who differ in one genetic characteristic for which they are both

If two parents are mated with each other who differ in one genetic characteristic for which they are both homozygous

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mo ...

(each pure-bred), all offspring in the first generation (F1) are equal to the examined characteristic in genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

and phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

showing the dominant trait. This ''uniformity rule'' or ''reciprocity rule'' applies to all individuals of the F1-generation.

The principle of dominant inheritance discovered by Mendel states that in a heterozygote the dominant allele will cause the recessive allele to be "masked": that is, not expressed in the phenotype. Only if an individual is homozygous with respect to the recessive allele will the recessive trait be expressed. Therefore, a cross between a homozygous dominant and a homozygous recessive organism yields a heterozygous organism whose phenotype displays only the dominant trait.

The F1 offspring of Mendel's pea crosses always looked like one of the two parental varieties. In this situation of "complete dominance," the dominant allele had the same phenotypic effect whether present in one or two copies.

But for some characteristics, the F1 hybrids have an appearance ''in between'' the phenotypes of the two parental varieties. A cross between two four o'clock (''Mirabilis jalapa

''Mirabilis jalapa'', the marvel of Peru or four o'clock flower, is the most commonly grown ornamental species of ''Mirabilis'' plant, and is available in a range of colors. ''Mirabilis'' in Latin means wonderful and Xalapa, Jalapa (or Xalapa) is ...

'') plants shows an exception to Mendel's principle, called ''incomplete dominance''. Flowers of heterozygous plants have a phenotype somewhere between the two homozygous genotypes. In cases of intermediate inheritance (incomplete dominance) in the F1-generation Mendel's principle of uniformity in genotype and phenotype applies as well. Research about intermediate inheritance was done by other scientists. The first was Carl Correns

Carl Erich Correns (19 September 1864 – 14 February 1933) was a German botanist and geneticist notable primarily for his independent discovery of the principles of heredity, which he achieved simultaneously but independently of the botanist ...

with his studies about Mirabilis jalapa.

Law of Segregation of genes

genetic carrier

A hereditary carrier (genetic carrier or just carrier), is a person or other organism that has inherited a recessive allele for a genetic trait or mutation but usually does not display that trait or show symptoms of the disease. Carriers are, ho ...

s), 25% are homozygous with the recessive trait and therefore express the recessive trait in the phenotype. The genotypic ratio is 1 : 2 : 1, the phenotypic ratio is 3 : 1.

In the pea plant example, the capital "B" represents the dominant allele for purple blossom and lowercase "b" represents the recessive allele for white blossom. The pistil

Gynoecium (; ) is most commonly used as a collective term for the parts of a flower that produce ovules and ultimately develop into the fruit and seeds. The gynoecium is the innermost whorl of a flower; it consists of (one or more) ''pistils'' ...

plant and the pollen

Pollen is a powdery substance produced by seed plants. It consists of pollen grains (highly reduced microgametophytes), which produce male gametes (sperm cells). Pollen grains have a hard coat made of sporopollenin that protects the gametophyt ...

plant are both F1-hybrids with genotype "B b". Each has one allele for purple and one allele for white. In the offspring, in the F2-plants in the Punnett-square, three combinations are possible. The genotypic ratio is 1 ''BB'' : 2 ''Bb'' : 1 ''bb''. But the phenotypic ratio of plants with purple blossoms to those with white blossoms is 3 : 1 due to the dominance of the allele for purple. Plants with homozygous "b b" are white flowered like one of the grandparents in the P-generation.

In cases of incomplete dominance

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and ...

the same segregation of alleles takes place in the F2-generation, but here also the phenotypes show a ratio of 1 : 2 : 1, as the heterozygous are different in phenotype from the homozygous because the genetic expression of one allele compensates the missing expression of the other allele only partially. This results in an intermediate inheritance which was later described by other scientists.

In some literature sources the principle of segregation is cited as "first law". Nevertheless, Mendel did his crossing experiments with heterozygous plants after obtaining these hybrids by crossing two purebred plants, discovering the principle of dominance and uniformity first. Neil A. Campbell, Jane B. Reece

Jane B. Reece (born 15 April 1944) is an American scientist and textbook author. Along with American biologist Neil Campbell, she wrote the widely used Campbell/Reece ''Biology'' textbooks.

Reece received an A.B. in Biology from Harvard Univers ...

: Biologie. Spektrum-Verlag 2003, page 293-315.

Molecular proof of segregation of genes was subsequently found through observation of meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately resu ...

by two scientists independently, the German botanist Oscar Hertwig

Oscar Hertwig (21 April 1849 in Friedberg – 25 October 1922 in Berlin) was a German embryologist and zoologist known for his research in developmental biology and evolution. Hertwig is credited as the first man to observe sexual reproduction ...

in 1876, and the Belgian zoologist Edouard Van Beneden in 1883. Most alleles are located in chromosomes

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

in the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (pl. nuclei; from Latin or , meaning ''kernel'' or ''seed'') is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryotic cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, h ...

. Paternal and maternal chromosomes get separated in meiosis, because during spermatogenesis

Spermatogenesis is the process by which haploid spermatozoa develop from germ cells in the seminiferous tubules of the testis. This process starts with the mitotic division of the stem cells located close to the basement membrane of the tubule ...

the chromosomes are segregated on the four sperm cells that arise from one mother sperm cell, and during oogenesis

Oogenesis, ovogenesis, or oögenesis is the differentiation of the ovum (egg cell) into a cell competent to further develop when fertilized. It is developed from the primary oocyte by maturation. Oogenesis is initiated in the embryonic stage.

O ...

the chromosomes are distributed between the polar bodies

A polar body is a small haploid cell that is formed at the same time as an egg cell during oogenesis, but generally does not have the ability to be fertilized. It is named from its polar position in the egg.

When certain diploid cells in animals ...

and the egg cell

The egg cell, or ovum (plural ova), is the female reproductive cell, or gamete, in most anisogamous organisms (organisms that reproduce sexually with a larger, female gamete and a smaller, male one). The term is used when the female gamete is ...

. Every individual organism contains two alleles for each trait. They segregate (separate) during meiosis such that each gamete

A gamete (; , ultimately ) is a haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as sex cells. In species that produce t ...

contains only one of the alleles. When the gametes unite in the zygote

A zygote (, ) is a eukaryotic cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes. The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individual organism.

In multicellula ...

the alleles—one from the mother one from the father—get passed on to the offspring. An offspring thus receives a pair of alleles for a trait by inheriting homologous chromosome

A couple of homologous chromosomes, or homologs, are a set of one maternal and one paternal chromosome that pair up with each other inside a cell during fertilization. Homologs have the same genes in the same loci where they provide points alon ...

s from the parent organisms: one allele for each trait from each parent. Heterozygous individuals with the dominant trait in the phenotype are genetic carrier

A hereditary carrier (genetic carrier or just carrier), is a person or other organism that has inherited a recessive allele for a genetic trait or mutation but usually does not display that trait or show symptoms of the disease. Carriers are, ho ...

s of the recessive trait.

Law of Independent Assortment

The Law of Independent Assortment states that alleles for separate traits are passed independently of one another. That is, the biological selection of an allele for one trait has nothing to do with the selection of an allele for any other trait. Mendel found support for this law in his dihybrid cross experiments. In his monohybrid crosses, an idealized 3:1 ratio between dominant and recessive phenotypes resulted. In dihybrid crosses, however, he found a 9:3:3:1 ratios. This shows that each of the two alleles is inherited independently from the other, with a 3:1 phenotypic ratio for each.

Independent assortment occurs in

The Law of Independent Assortment states that alleles for separate traits are passed independently of one another. That is, the biological selection of an allele for one trait has nothing to do with the selection of an allele for any other trait. Mendel found support for this law in his dihybrid cross experiments. In his monohybrid crosses, an idealized 3:1 ratio between dominant and recessive phenotypes resulted. In dihybrid crosses, however, he found a 9:3:3:1 ratios. This shows that each of the two alleles is inherited independently from the other, with a 3:1 phenotypic ratio for each.

Independent assortment occurs in eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

organisms during meiotic metaphase I, and produces a gamete with a mixture of the organism's chromosomes. The physical basis of the independent assortment of chromosomes is the random orientation of each bivalent chromosome along the metaphase plate with respect to the other bivalent chromosomes. Along with crossing over, independent assortment increases genetic diversity by producing novel genetic combinations.

There are many deviations from the principle of independent assortment due to genetic linkage

Genetic linkage is the tendency of DNA sequences that are close together on a chromosome to be inherited together during the meiosis phase of sexual reproduction. Two genetic markers that are physically near to each other are unlikely to be separ ...

.

Of the 46 chromosomes in a normal diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

human cell, half are maternally derived (from the mother's egg

An egg is an organic vessel grown by an animal to carry a possibly fertilized egg cell (a zygote) and to incubate from it an embryo within the egg until the embryo has become an animal fetus that can survive on its own, at which point the a ...

) and half are paternally derived (from the father's sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, whi ...

). This occurs as sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

involves the fusion of two haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Sets of chromosomes refer to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, respectively ...

gametes (the egg and sperm) to produce a zygote and a new organism, in which every cell has two sets of chromosomes (diploid). During gametogenesis

Gametogenesis is a biological process by which diploid or haploid precursor cells undergo cell division and differentiation to form mature haploid gametes. Depending on the biological life cycle of the organism, gametogenesis occurs by meiotic d ...

the normal complement of 46 chromosomes needs to be halved to 23 to ensure that the resulting haploid gamete can join with another haploid gamete to produce a diploid organism.

In independent assortment, the chromosomes that result are randomly sorted from all possible maternal and paternal chromosomes. Because zygotes end up with a mix instead of a pre-defined "set" from either parent, chromosomes are therefore considered assorted independently. As such, the zygote can end up with any combination of paternal or maternal chromosomes. For human gametes, with 23 chromosomes, the number of possibilities is 223 or 8,388,608 possible combinations. This contributes to the genetic variability of progeny. Generally, the recombination of genes has important implications for many evolutionary processes.

Mendelian trait

A Mendelian trait is one whose inheritance follows Mendel’s principles—namely, the trait depends only on a singlelocus

Locus (plural loci) is Latin for "place". It may refer to:

Entertainment

* Locus (comics), a Marvel Comics mutant villainess, a member of the Mutant Liberation Front

* ''Locus'' (magazine), science fiction and fantasy magazine

** ''Locus Award' ...

, whose alleles

An allele (, ; ; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος ''állos'', "other") is a variation of the same sequence of nucleotides at the same place on a long DNA molecule, as described in leading textbooks on genetics and evolution.

::"The chro ...

are either dominant or recessive.

Many traits are inherited in a non-Mendelian fashion.

Non-Mendelian inheritance

Mendel himself warned that care was needed in extrapolating his patterns to other organisms or traits. Indeed, many organisms have traits whose inheritance works differently from the principles he described; these traits are called non-Mendelian.Khan AcademyVariations on Mendel's laws (overview)

/ref> For example, Mendel focused on traits whose genes have only two alleles, such as "A" and "a". However, many genes have more than two alleles. He also focused on traits determined by a single gene. But some traits, such as height, depend on many genes rather than just one. Traits dependent on multiple genes are called

polygenic traits

A quantitative trait locus (QTL) is a locus (section of DNA) that correlates with variation of a quantitative trait in the phenotype of a population of organisms. QTLs are mapped by identifying which molecular markers (such as SNPs or AFLPs) co ...

.See also

*List of Mendelian traits in humans

Mendelian traits in humans are human traits that are substantially influenced by Mendelian inheritance. Most — if not all — Mendelian triaits are also influenced by other genes, the environment, immune responses, and chance. Therefore no ...

* Mendelian disease

A genetic disorder is a health problem caused by one or more abnormalities in the genome. It can be caused by a mutation in a single gene (monogenic) or multiple genes (polygenic) or by a chromosomal abnormality. Although polygenic disorders ...

s (monogenic disease)

* Mendelian error

A Mendelian error in the genetic analysis of a species, describes an allele in an individual which could not have been received from either of its biological parents by Mendelian inheritance. Inheritance is defined by a set of related individual ...

* Particulate inheritance

Particulate inheritance is a pattern of inheritance discovered by Mendelian genetics theorists, such as William Bateson, Ronald Fisher or Gregor Mendel himself, showing that phenotypic traits can be passed from generation to generation through " ...

* Punnett square

References

Notes

* * *External links

Khan Academy, video lecture

Mendel's principles of Inheritance

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mendelian Inheritance Classical genetics

Genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar wor ...

it:Gregor Mendel#Le leggi di Mendel