Melqart on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Melqart (also Melkarth or Melicarthus) was the tutelary god of the

Melqart (also Melkarth or Melicarthus) was the tutelary god of the

Melqart is likely to have been the particular

Melqart is likely to have been the particular

Melqart (also Melkarth or Melicarthus) was the tutelary god of the

Melqart (also Melkarth or Melicarthus) was the tutelary god of the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

n city-state of Tyre and a major deity in the Phoenician and Punic pantheons. Often titled the "Lord of Tyre" (''Ba‘al

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity. From its use among people, it came to be applied to ...

Ṣūr''), he was also known as the Son of Baal

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during Ancient Near East, antiquity. From its use among people, it cam ...

or El (the Ruler of the Universe), King of the Underworld, and Protector of the Universe. He symbolized the annual cycle of vegetation and was associated with the Phoenician maternal goddess Astarte

Astarte (; , ) is the Hellenized form of the Ancient Near Eastern goddess Ashtart or Athtart (Northwest Semitic), a deity closely related to Ishtar (East Semitic), who was worshipped from the Bronze Age through classical antiquity. The name i ...

.

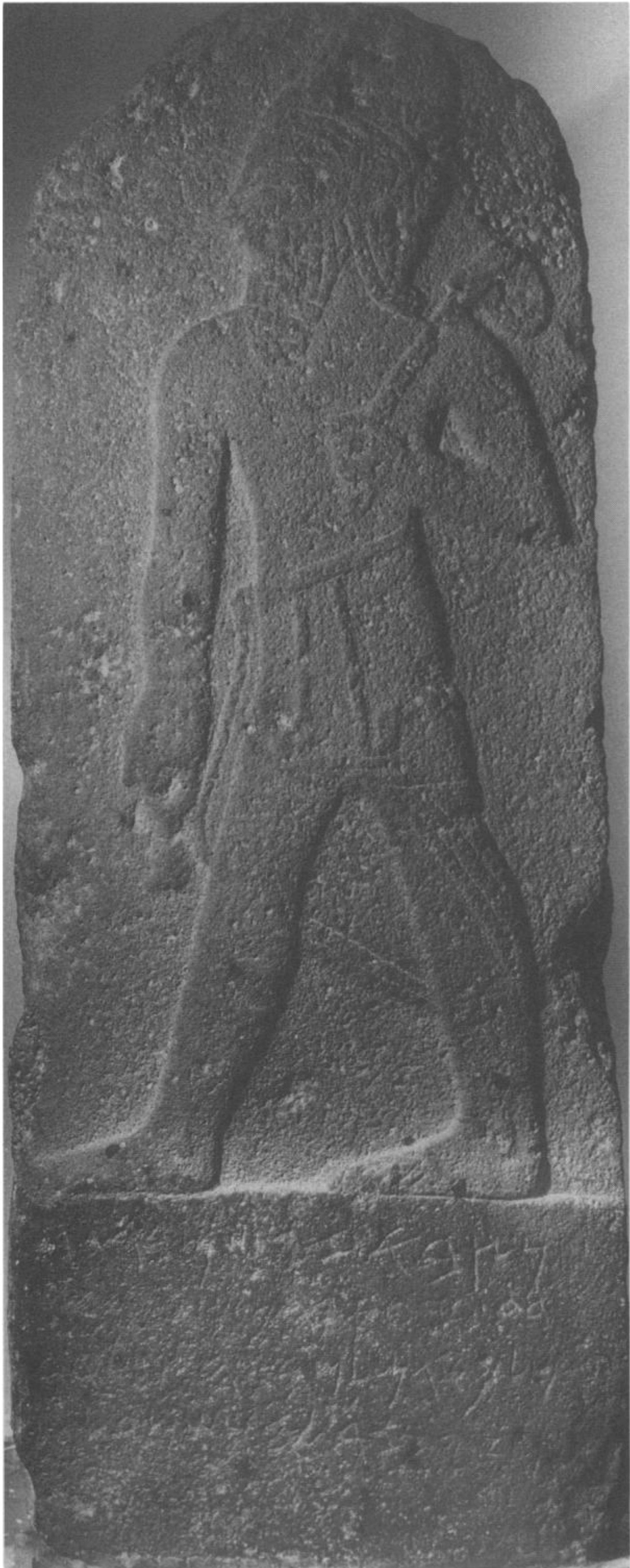

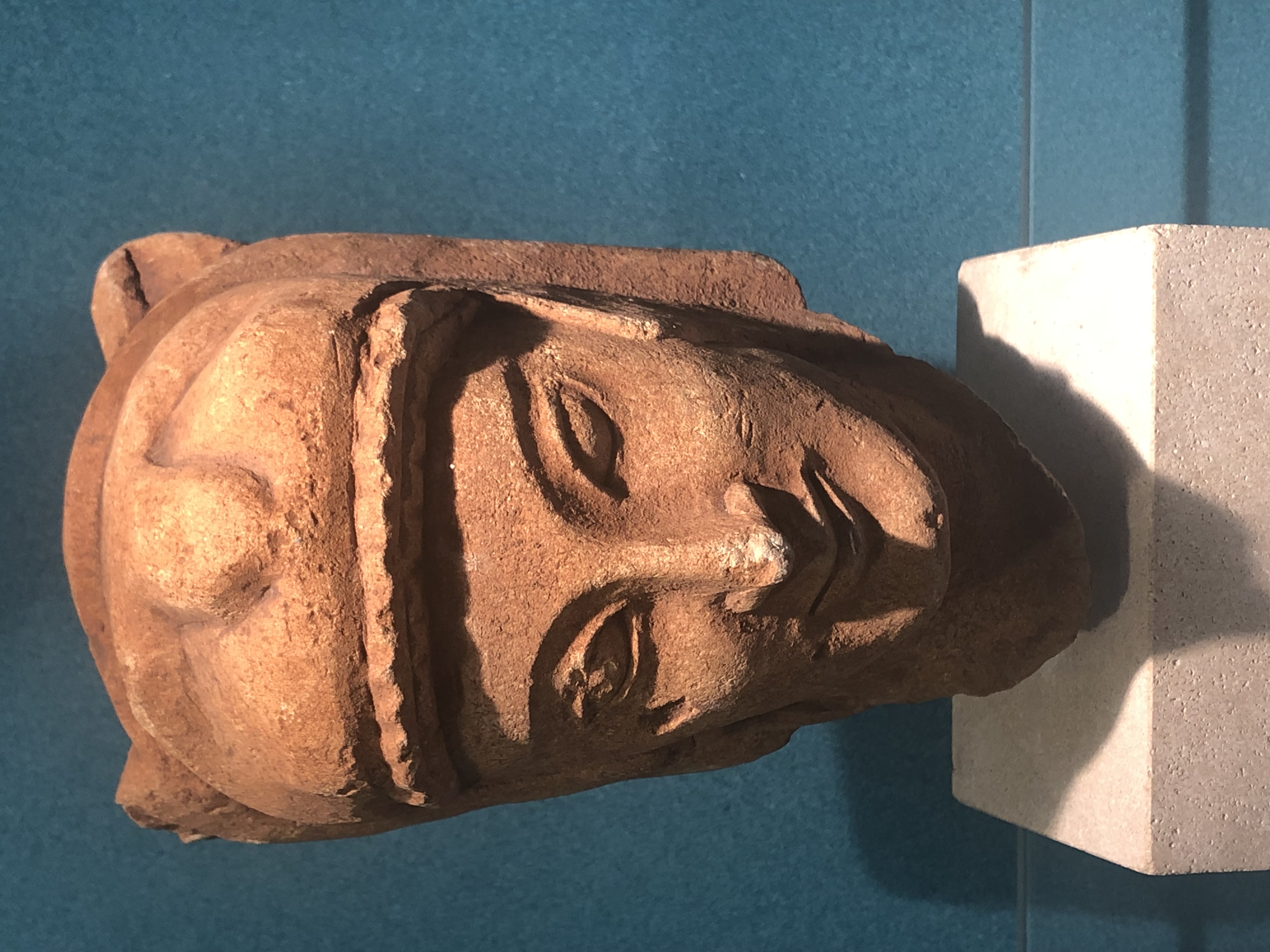

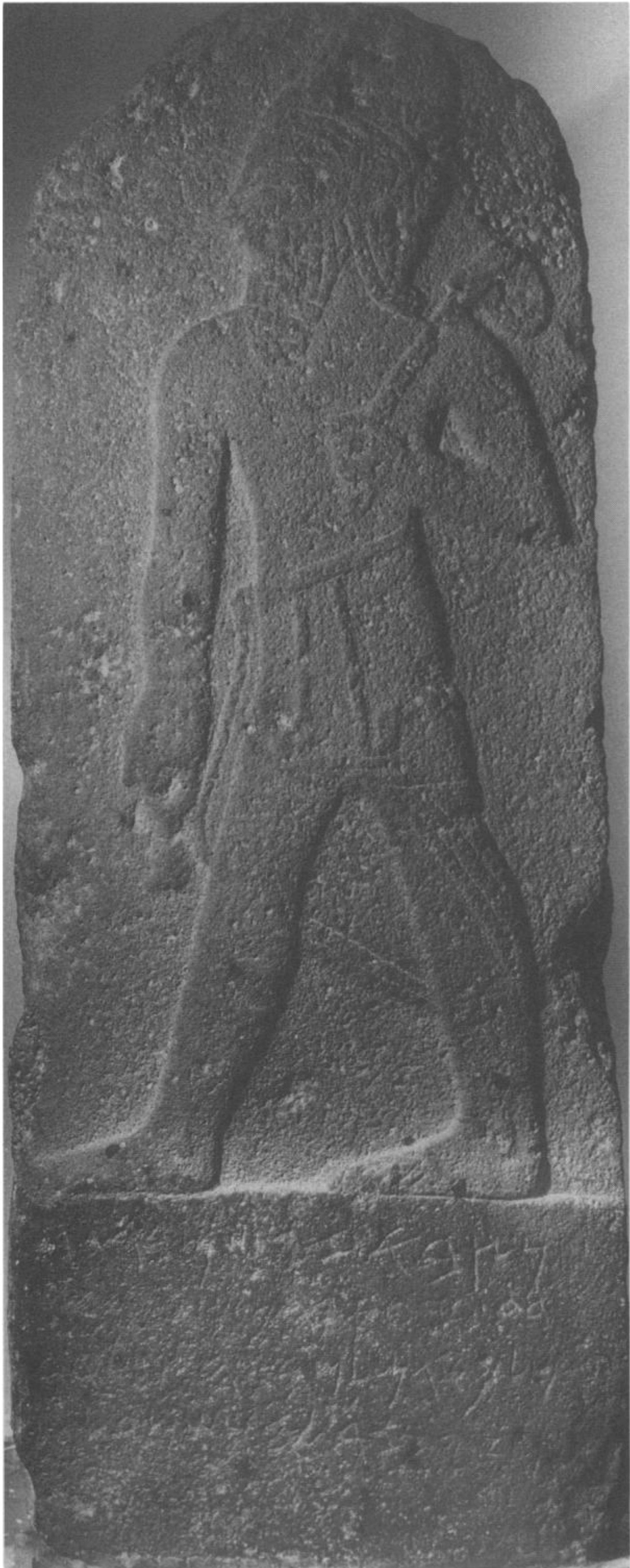

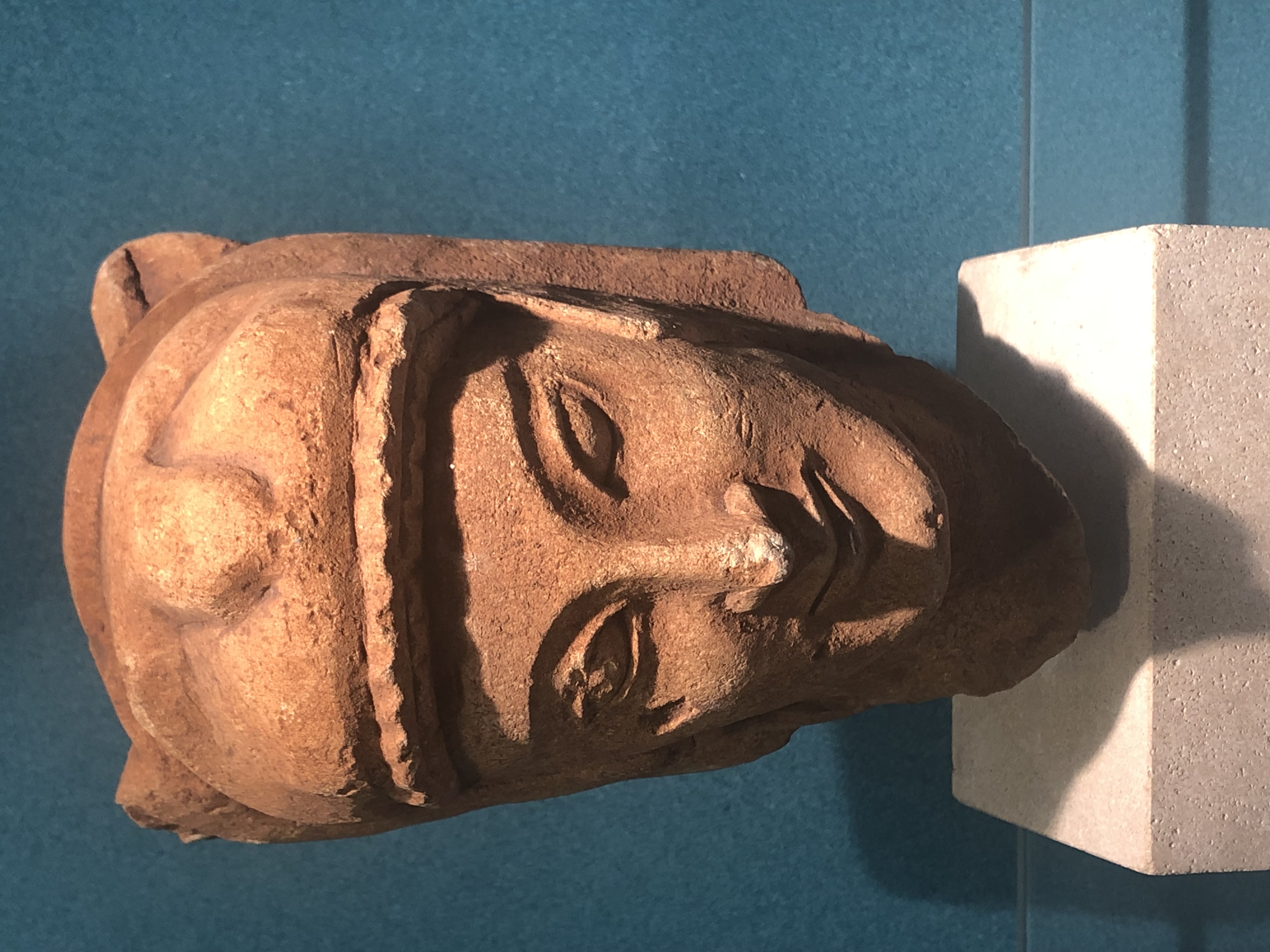

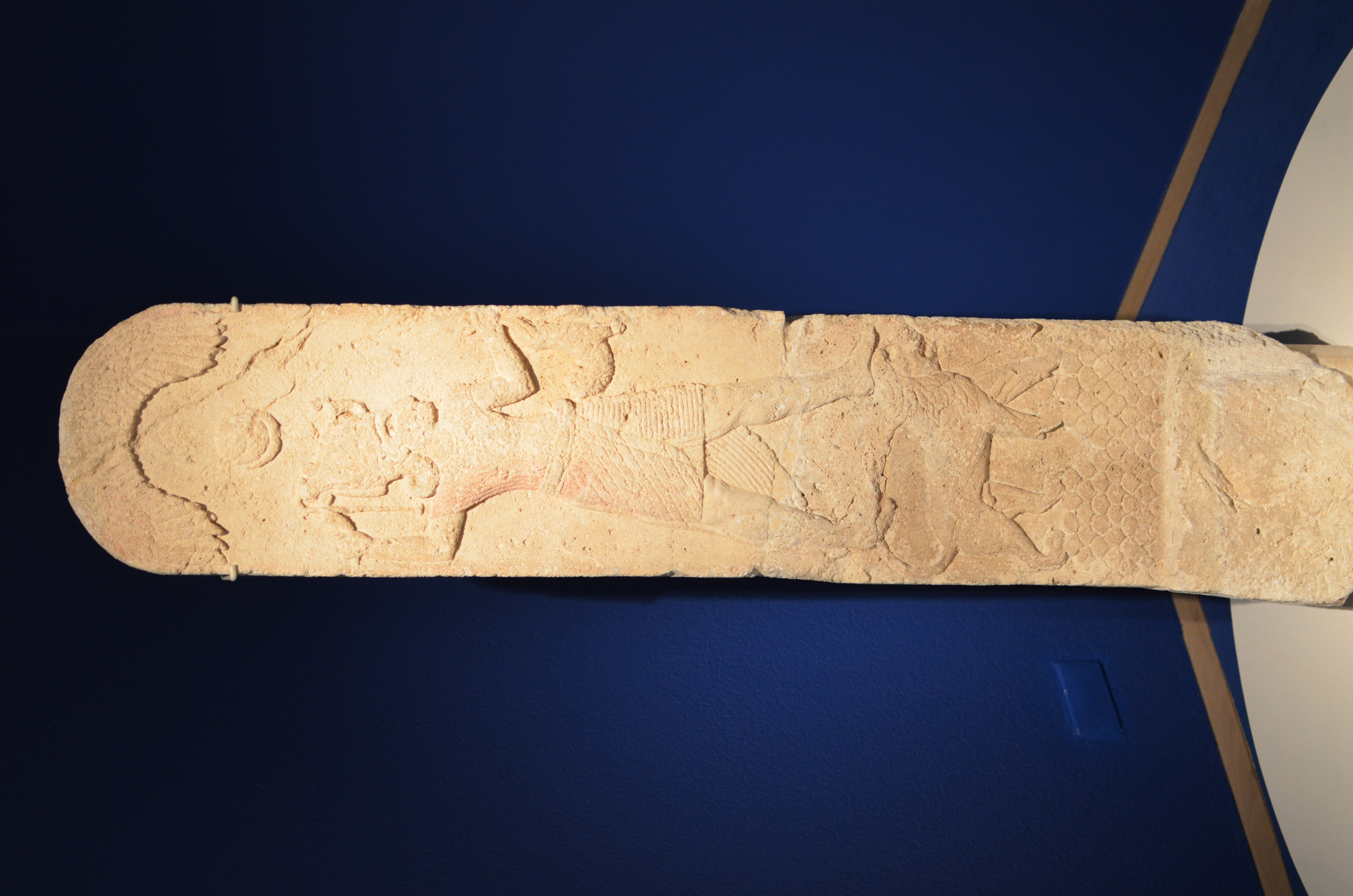

Melqart was typically depicted as a bearded figure, dressed only in a rounded hat and loincloth. Reflecting his dual role as both protector of the world and ruler of the underworld, he was often shown holding an Egyptian ankh or lotus flower as a symbol of life and a fenestrated axe as a symbol of death.

As Tyrian trade and settlement expanded, Melqart became venerated in Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

n and Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

cultures across the Mediterranean, especially its colonies of Carthage and Cadiz. During the high point of Phoenician civilization between 1000 and 500 BCE, Melqart was associated with other pantheons and often venerated accordingly. Most notably, he was identified with the Greek Herakles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptive ...

(Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Gr ...

) since at least the sixth century BCE, and eventually became interchangeable with his Greek counterpart.

Etymology

Melqart was written in the Phoenicianabjad

An abjad (, ar, أبجد; also abgad) is a writing system in which only consonants are represented, leaving vowel sounds to be inferred by the reader. This contrasts with other alphabets, which provide graphemes for both consonants and vowels ...

as ( phn, 𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕 ''Malqārt''). Edward Lipinski theorizes that it was derived from ( ''Mīlk-Qārtī''), which means "King of the City". The name is sometimes transcribed as Melkart, Melkarth, or Melgart. In Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo- syllabi ...

, his name was written Milqartu.

To the Greeks and the Romans, who identified Melqart with Hercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Gr ...

, he was often distinguished as the .

Cult

Melqart is likely to have been the particular

Melqart is likely to have been the particular Ba‘al

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity. From its use among people, it came to be applied to ...

found in the Tanakh

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''

''

1 Kings 16.31–10.26) whose worship was prominently introduced to

The first occurrence of the name is in the 9th-century BCE the "Ben-Hadad" inscription found in 1939 north of

The first occurrence of the name is in the 9th-century BCE the "Ben-Hadad" inscription found in 1939 north of

''Or.'' 33.47

who mentions the beautiful pyre which the Tarsians used to build for their Heracles, referring here to the

Melqart - World History EncyclopediaTemple of Melqart

a circumstantial review that gives a good sketch of Aubet's book, in which Melqart figures strongly; Aubet concentrates on Tyre and its colonies and ends, ca 550 BCE, with the rise of Carthage.

L'iconographie de Melqart (article in PDF eng.)

{{Authority control West Semitic gods Tutelary deities Deities in the Hebrew Bible Phoenician mythology Hellenistic Asian deities Heracles Baal

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

by King Ahab

Ahab (; akk, 𒀀𒄩𒀊𒁍 ''Aḫâbbu'' 'a-ḫa-ab-bu'' grc-koi, Ἀχαάβ ''Achaáb''; la, Achab) was the seventh king of Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), Israel, the son and successor of King Omri and the husband of Jezebel of Sidon, ...

and largely eradicated by King Jehu

) as depicted on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

, succession = King of Northern Israel

, reign = c. 841–814 BCE

, coronation = Ramoth-Gilead, Israel

, birth_date = c. 882 BCE

, death_date = c. 814 BCE

, burial_place = ...

. In 1 Kings 18.27, it is possible that there is a mocking reference to legendary Heraclean journeys made by the god and to the annual ''egersis'' ("awakening") of the god:

And it came to pass at noon that Elijah mocked them and said, "Cry out loud: for he is a god; either he is lost in thought, or he has wandered away, or he is on a journey, or perhaps he is sleeping and must be awakened."The Hellenistic novelist,

Heliodorus of Emesa

Heliodorus Emesenus or Heliodorus of Emesa ( grc, Ἡλιόδωρος ὁ Ἐμεσηνός) is the author of the ancient Greek novel called the ''Aethiopica'' () or ''Theagenes and Chariclea'' (), which has been dated to the 220s or 370s AD.

Ide ...

, in his ''Aethiopica

The ''Aethiopica'' (; grc, Αἰθιοπικά, , 'Ethiopian Stories') or ''Theagenes and Chariclea'' (; grc, Θεαγένης καὶ Χαρίκλεια, link=no, ) is an ancient Greek novel which has been dated to the 220s or 370s AD. It was ...

,'' refers to the dancing

Dance is a performing art form consisting of sequences of movement, either improvised or purposefully selected. This movement has aesthetic and often symbolic value. Dance can be categorized and described by its choreography, by its repertoire ...

of sailors in honor of the Tyrian Heracles: "Now they leap spiritedly into the air, now they bend their knees to the ground and revolve on them like persons possessed".

The historian Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

recorded (2.44):

In the wish to get the best information that I could on these matters, I made a voyage to Tyre in Phoenicia, hearing there was a temple of Heracles at that place, very highly venerated. I visited the temple, and found it richly adorned with a number of offerings, among which were two pillars, one of pure gold, the other of '' smaragdos'', shining with great brilliance at night. In a conversation which I held with the priests, I inquired how long their temple had been built, and found by their answer that they, too, differed from the Hellenes. They said that the temple was built at the same time that the city was founded, and that the foundation of the city took place 2,300 years ago. In Tyre I remarked another temple where the same god was worshipped as the Thasian Heracles. So I went on toThasos Thasos or Thassos ( el, Θάσος, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area. The island has an area of and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate re ..., where I found a temple of Heracles which had been built by the Phoenicians who colonised that island when they sailed in search ofEuropa Europa may refer to: Places * Europe * Europa (Roman province), a province within the Diocese of Thrace * Europa (Seville Metro), Seville, Spain; a station on the Seville Metro * Europa City, Paris, France; a planned development * Europa Cliff .... Even this was five generations earlier than the time when Heracles, son ofAmphitryon Amphitryon (; Ancient Greek: Ἀμφιτρύων, ''gen''.: Ἀμφιτρύωνος; usually interpreted as "harassing either side", Latin: Amphitruo), in Greek mythology, was a son of Alcaeus, king of Tiryns in Argolis. His mother was named ei ..., was born in Hellas. These researches show plainly that there is an ancient god Heracles; and my own opinion is that those Hellenes act most wisely who build and maintain two temples of Heracles, in the one of which the Heracles worshipped is known by the name of Olympian, and has sacrifice offered to him as an immortal, while in the other the honours paid are such as are due to a hero.

Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

records (''Antiquities'' 8.5.3), following Menander of Ephesus Menander of Ephesus ( grc-gre, Μένανδρος; fl. c. early 2nd century BC) was the historian whose lost work on the history of Tyre was used by Josephus, who quotes Menander's list of kings of Tyre in his apologia for the Jews, ''Against Apio ...

the historian, concerning King Hiram I

Hiram I ( Phoenician: 𐤇𐤓𐤌 ''Ḥirōm'' "my brother is exalted"; Hebrew: ''Ḥīrām'', Modern Arabic: حيرام, also called ''Hirom'' or ''Huram'')

was the Phoenician king of Tyre according to the Hebrew Bible. His regnal years have b ...

of Tyre (c. 965–935 BCE):

He also went and cut down materials of timber out of the mountain calledThe annual celebration of the revival of Melqart's "awakening" may identify Melqart as aLebanon Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ..., for the roof of temples; and when he had pulled down the ancient temples, he both built the temple of Heracles and that of`Ashtart Astarte (; , ) is the Hellenized form of the Ancient Near Eastern goddess Ashtart or Athtart (Northwest Semitic), a deity closely related to Ishtar ( East Semitic), who was worshipped from the Bronze Age through classical antiquity. The name ...; and he was the first to celebrate the awakening (''egersis'') of Heracles in the month Peritius.

life-death-rebirth deity

A dying-and-rising, death-rebirth, or resurrection deity is a religious motif in which a god or goddess dies and is resurrected.Leeming, "Dying god" (2004)Miles 2009, 193 Examples of gods who die and later return to life are most often cited f ...

.

The Roman Emperor Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa (Roman province), Africa. As a young man he advanced thro ...

was a native of Lepcis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by other names in antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Originally a 7th-centuryBC Phoenician foundation, it was great ...

in Africa, an originally Phoenician city where worship of Melqart was widespread. He is known to have constructed in Rome a temple dedicated to "Liber

In ancient Roman religion and mythology, Liber ( , ; "the free one"), also known as Liber Pater ("the free Father"), was a god of viticulture and wine, male fertility and freedom. He was a patron deity of Rome's plebeians and was part of the ...

and Hercules", and it is assumed that the Emperor, seeking to honour the god of his native city, identified Melqart with the Roman god Liber.

Archaeological evidence

Aleppo

)), is an adjective which means "white-colored mixed with black".

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, image_map1 =

...

in today northern Syria; it had been erected by the son of the king of Aram

Aram may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Aram'' (film), 2002 French action drama

* Aram, a fictional character in Japanese manga series '' MeruPuri''

* Aram Quartet, an Italian music group

* ''Aram'' (Kural book), the first of the three ...

"for his lord Melqart, which he vowed to him and he heard his voice".

Archaeological evidence for Melqart's cult is found earliest in Tyre and seems to have spread westward with the Phoenician colonies established by Tyre as well as eventually overshadowing the worship of Eshmun in Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

. The name of Melqart was invoked in oaths sanctioning contracts, according to Dr. Aubet, thus it was customary to build a temple to Melqart, as protector of Tyrian traders, in each new Phoenician colony: at Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

, the temple to Melqart is as early as the earliest vestiges of Phoenician occupation. (The Greeks followed a parallel practice in respect to Heracles.) Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

even sent a yearly tribute of 10% of the public treasury to the god in Tyre up until the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

.

In Tyre, the high priest of Melqart ranked second only to the king. Many names in Carthage reflected this importance of Melqart, for example, the names Hamilcar __NOTOC__

Hamilcar ( xpu, 𐤇𐤌𐤋𐤊 , ,. or , , "Melqart is Gracious"; grc-gre, Ἁμίλκας, ''Hamílkas'';) was a common Carthaginian masculine given name. The name was particularly common among the ruling families of ancient Carthage. ...

and Bomilcar; but ''Ba‘l'' "Lord" as a name-element in Carthaginian names such as Hasdrubal and Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

almost certainly does not refer to Melqart but instead refers to Ba`al Hammon, chief god of Carthage, a god identified by Greeks with Cronus

In Ancient Greek religion and mythology, Cronus, Cronos, or Kronos ( or , from el, Κρόνος, ''Krónos'') was the leader and youngest of the first generation of Titans, the divine descendants of the primordial Gaia (Mother Earth) and ...

and by Romans with Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

, or is simply used as a title.

Melqart protected the Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

areas of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, such as Cefalù, which was known under Carthaginian rule as "Cape Melqart" ( xpu, 𐤓𐤔 𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕, ). Melqart's head, indistinguishable from a Heracles, appeared on its coins of the 4th century BCE.

The Cippi of Melqart

The Cippi of Melqart are a pair of Phoenician marble cippi that were unearthed in Malta under undocumented circumstances and dated to the 2nd century BC. These are votive offerings to the god Melqart, and are inscribed in two languages, Ancie ...

, found on Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and dedicated to the god as an ex voto

An ex-voto is a votive offering to a saint or to a divinity; the term is usually restricted to Christian examples. It is given in fulfillment of a vow (hence the Latin term, short for ''ex voto suscepto'', "from the vow made") or in gratitude o ...

offering, provided the key to understanding the Phoenician language

Phoenician ( ) is an extinct language, extinct Canaanite languages, Canaanite Semitic languages, Semitic language originally spoken in the region surrounding the cities of Tyre, Lebanon, Tyre and Sidon. Extensive Tyro-Sidonian trade and commerci ...

, as the inscriptions on the cippi were written in both Phoenician and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

.

Temple sites

Temples to Melqart are found at at least three Phoenician/Punic sites in Spain: Cádiz, Ibiza in theBalearic Islands

The Balearic Islands ( es, Islas Baleares ; or ca, Illes Balears ) are an archipelago in the Balearic Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The archipelago is an autonomous community and a province of Spain; its capital is ...

and Cartagena. Near Gades/Gádeira (modern Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

) was the westernmost temple of Tyrian Heracles, near the eastern shore of the island (Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

3.5.2–3). Strabo notes (3.5.5–6) that the two bronze pillars within the temple, each 8 cubits high, were widely proclaimed to be the true Pillars of Heracles

The Pillars of Hercules ( la, Columnae Herculis, grc, Ἡράκλειαι Στῆλαι, , ar, أعمدة هرقل, Aʿmidat Hiraql, es, Columnas de Hércules) was the phrase that was applied in Antiquity to the promontories that flank t ...

by many who had visited the place and had sacrificed to Heracles there. Strabo believes the account to be fraudulent, in part noting that the inscriptions on those pillars mentioned nothing about Heracles, speaking only of the expenses incurred by the Phoenicians in their making.

Another temple to Melqart was at Ebyssus (Ibiza

Ibiza (natively and officially in ca, Eivissa, ) is a Spanish island in the Mediterranean Sea off the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. It is from the city of Valencia. It is the third largest of the Balearic Islands, in Spain. Its l ...

), in one of four Phoenician sites on the island's south coast. In 2004 a highway crew in the Avinguda Espanya, (one of the main routes into Ibiza), uncovered a further Punic temple in the excavated roadbed. Texts found mention Melqart among other Punic gods Eshmun, Astarte and Baʻl.

Another Iberian temple to Melqart has been identified at Carthago Nova

Cartagena () is a Spanish city and a major naval station on the Mediterranean coast, south-eastern Iberia. As of January 2018, it has a population of 218,943 inhabitants, being the region's second-largest municipality and the country's sixth-la ...

( Cartagena). The Tyrian god's protection extended to the sacred promontory (Cape Saint Vincent

Cape St. Vincent ( pt, Cabo de São Vicente, ) is a headland in the Municipalities of Portugal, municipality of Vila do Bispo, in the Algarve, southern Portugal. It is the southwesternmost point of Portugal and of mainland Europe.

History

Cape ...

) of the Iberian peninsula, the westernmost point of the known world, ground so sacred it was forbidden even to spend the night.

Another temple to Melqart was at Lixus Lixus may refer to:

* ''lixus'', the Latin word for "boiled"

* Lixus (ancient city) in Morocco

* ''Lixus (beetle)'', a genus of true weevils

* Lixus, one of the sons of Aegyptus and Caliadne

Caliadne (; Ancient Greek: Καλιάδνης ) or Cali ...

, on the Atlantic coast of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

.

Hannibal and Melqart

Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

was a faithful worshiper of Melqart: the Roman historian Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Ancient Rome, Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditiona ...

records the story that just before setting off on his march to Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

he made a pilgrimage to Gades, the most ancient seat of Phoenician worship in the west. Hannibal strengthened himself spiritually by prayer and sacrifice at the Altar of Melqart. He returned to New Carthage with his mind focused on the god and on the eve of departure to Italy he saw a strange vision which he believed was sent by Melqart.Livy XXI, 21-23

A youth of divine beauty appeared to Hannibal in the night. The youth told Hannibal he had been sent by supreme deity, Jupiter, to guide the son of Hamilcar __NOTOC__

Hamilcar ( xpu, 𐤇𐤌𐤋𐤊 , ,. or , , "Melqart is Gracious"; grc-gre, Ἁμίλκας, ''Hamílkas'';) was a common Carthaginian masculine given name. The name was particularly common among the ruling families of ancient Carthage. ...

to Italy. “Follow me,” said the ghostly visitor, “and see that that thou look not behind thee.” Hannibal followed the instructions of the visitor. His curiosity, however, overcame him, and as he turned his head, Hannibal saw a serpent crashing through forest and thicket causing destruction everywhere. It moved as a black tempest with claps of thunder and flashes of lightning gathered behind the serpent. When Hannibal asked the meaning of the vision the being replied, “What thou beholdest is the desolation of Italy. Follow thy star and inquire no farther into the dark counsels of heaven.”

Graeco-Roman traditions

It was suggested by some writers that the PhoenicianMelicertes

In Greek mythology, Melicertes ( grc, Μελικέρτης, Melikértēs, sometimes Melecertes), later called Palaemon or Palaimon (), was a Boeotian prince as the son of King Athamas and Ino, daughter of King Cadmus of Thebes. He was the brot ...

son of Ino found in Greek mythology was in origin a reflection of Melqart. Though no classical source explicitly connects the two, Ino is the daughter of Cadmus

In Greek mythology, Cadmus (; grc-gre, Κάδμος, Kádmos) was the legendary Phoenician founder of Boeotian Thebes. He was the first Greek hero and, alongside Perseus and Bellerophon, the greatest hero and slayer of monsters before the da ...

of Tyre. Lewis Farnell thought not, referring in 1916 to "the accidental resemblance in sound of Melikertes and Melqart, seeing that Melqart, the bearded god, had no affinity in form or myth with the child- or boy-deity, and was moreover always identified with Herakles: nor do we know anything about Melqart that would explain the figure of Ino that is aboriginally inseparable from Melikertes."

Athenaeus

Athenaeus of Naucratis (; grc, Ἀθήναιος ὁ Nαυκρατίτης or Nαυκράτιος, ''Athēnaios Naukratitēs'' or ''Naukratios''; la, Athenaeus Naucratita) was a Greek rhetorician and grammarian, flourishing about the end of th ...

(392d) summarizes a story by Eudoxus of Cnidus

Eudoxus of Cnidus (; grc, Εὔδοξος ὁ Κνίδιος, ''Eúdoxos ho Knídios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer, mathematician, scholar, and student of Archytas and Plato. All of his original works are lost, though some fragments are ...

(c. 355 BCE) telling how Heracles

Heracles ( ; grc-gre, Ἡρακλῆς, , glory/fame of Hera), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of Zeus and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptive ...

the son of Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=Genitive case, genitive Aeolic Greek, Boeotian Aeolic and Doric Greek#Laconian, Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=Genitive case, genitive el, Δίας, ''D� ...

by Asteria (= ‘Ashtart ?) was killed by Typhon

Typhon (; grc, Τυφῶν, Typhôn, ), also Typhoeus (; grc, Τυφωεύς, Typhōeús, label=none), Typhaon ( grc, Τυφάων, Typháōn, label=none) or Typhos ( grc, Τυφώς, Typhṓs, label=none), was a monstrous serpentine giant an ...

in Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

. Heracles' companion Iolaus

In Greek mythology, Iolaus (; Ancient Greek: Ἰόλαος ''Iólaos'') was a Theban divine hero. He was famed for being Heracles' nephew and for helping with some of his Labors, and also for being one of the Argonauts.

Family

Iolaus was t ...

brought a quail to the dead god (presumably a roasted quail) and its delicious scent roused Heracles back to life. This purports to explain why the Phoenicians sacrifice quails to Heracles. It seems that Melqart had a companion similar to the Hellenic Iolaus, who was himself a native of the Tyrian colony of Thebes. Sanchuniathon

Sanchuniathon (; Ancient Greek: ; probably from Phoenician: , "Sakon has given"), also known as Sanchoniatho the Berytian, was a Phoenician author. His three works, originally written in the Phoenician language, survive only in partial paraphras ...

also makes Melqart under the name Malcarthos or Melcathros, the son of Hadad

Hadad ( uga, ), Haddad, Adad (Akkadian: 𒀭𒅎 '' DIM'', pronounced as ''Adād''), or Iškur ( Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions.

He was attested in Ebla as "Hadda" in c. 2500 BCE. ...

, who is normally identified with Zeus.

The '' Pseudo-Clementine Recognitions'' (10.24) speaks of the tombs of various gods, including "that of Heracles at Tyre, where he was burnt with fire." The Hellenic Heracles also died on a pyre, but the event was located on Mount Oeta

Mount Oeta (; el, Οίτη, polytonic , ''Oiti'', also transcribed as ''Oite'') is a mountain in Central Greece. A southeastern offshoot of the Pindus range, it is high. Since 1966, the core area of the mountain is a national park, and much of t ...

in Trachis

Trachis ( grc-gre, , ''Trakhís'') was a region in ancient Greece. Situated south of the river Spercheios, it was populated by the Malians. It was also a polis (city-state).

Its main town was also called ''Trachis'' until 426 BC, when it was re ...

. A similar tradition is recorded by Dio Chrysostom

Dio Chrysostom (; el, Δίων Χρυσόστομος ''Dion Chrysostomos''), Dion of Prusa or Cocceianus Dio (c. 40 – c. 115 AD), was a Greek orator, writer, philosopher and historian of the Roman Empire in the 1st century AD. Eighty of his ...

''Or.'' 33.47

who mentions the beautiful pyre which the Tarsians used to build for their Heracles, referring here to the

Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

n god Sandon.

In Nonnus' ''Dionysiaca'' (40.366–580) the Tyrian Heracles is very much a Sun-god

A solar deity or sun deity is a deity who represents the Sun, or an aspect of it. Such deities are usually associated with power and strength. Solar deities and Sun worship can be found throughout most of recorded history in various forms. The ...

. However, there is a tendency in the later Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

and Roman periods for almost all gods to develop solar attributes, and for almost all eastern gods to be identified with the Sun. Nonnus gives the title ''Astrochiton'' 'Starclad' to Tyrian Heracles and has his Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

recite a hymn to this Heracles, saluting him as "the son of Time, he who causes the threefold image of the Moon, the all-shining Eye of the heavens". Rain is ascribed to the shaking from his head of the waters of his bath in the eastern Ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

. His Sun-disk is praised as the cause of growth in plants. Then, in a climactic burst of syncretism, Dionysus identifies the Tyrian Heracles with Belus on the Euphrates, Ammon

Ammon (Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; he, עַמּוֹן ''ʻAmmōn''; ar, عمّون, ʻAmmūn) was an ancient Semitic-speaking nation occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Arnon and Jabbok, in p ...

in Libya, Apis by the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

, Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

n Cronus, Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n Zeus, Serapis

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian deity. The cult of Serapis was promoted during the third century BC on the orders of Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt as a means to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his r ...

, Zeus of Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Cronus

In Ancient Greek religion and mythology, Cronus, Cronos, or Kronos ( or , from el, Κρόνος, ''Krónos'') was the leader and youngest of the first generation of Titans, the divine descendants of the primordial Gaia (Mother Earth) and ...

, Phaethon

Phaethon (; grc, Φαέθων, Phaéthōn, ), also spelled Phaëthon, was the son of the Oceanid Clymene and the sun-god Helios in Greek mythology.

According to most authors, Phaethon is the son of Helios, and out of desire to have his par ...

, Mithras

Mithraism, also known as the Mithraic mysteries or the Cult of Mithras, was a Roman mystery religion centered on the god Mithras. Although inspired by Iranian worship of the Zoroastrian divinity (''yazata'') Mithra, the Roman Mithras is linke ...

, Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), in ancient times was a sacred precinct that served as the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. The oracle ...

c Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label=Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label= ...

, ''Gamos'' 'Marriage', and ''Paeon'' 'Healer'.

The Tyrian Heracles answers by appearing to Dionysus. There is red light in the fiery eyes of this shining god who clothed in a robe embroidered like the sky (presumably with various constellations). He has yellow, sparkling cheeks and a starry beard. The god reveals how he taught the primeval, earthborn inhabitants of Phoenicia how to build the first boat and instructed them to sail out to a pair of floating, rocky islands. On one of the islands there grew an olive tree with a serpent at its foot, an eagle at its summit, and which glowed in the middle with fire that burned but did not consume. Following the god's instructions, these primeval humans sacrificed the eagle to Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

, Zeus, and the other gods. Thereupon the islands rooted themselves to the bottom of the sea. On these islands the city of Tyre was founded.

Gregory of Nazianzus

Gregory of Nazianzus ( el, Γρηγόριος ὁ Ναζιανζηνός, ''Grēgorios ho Nazianzēnos''; ''Liturgy of the Hours'' Volume I, Proper of Saints, 2 January. – 25 January 390,), also known as Gregory the Theologian or Gregory N ...

(''Oratio'' 4.108) and Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Roman statesman, renowned scholar of antiquity, and writer serving in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senator'' w ...

(''Variae'' 1.2) relate how Tyrian Heracles and the nymph

A nymph ( grc, νύμφη, nýmphē, el, script=Latn, nímfi, label=Modern Greek; , ) in ancient Greek folklore is a minor female nature deity. Different from Greek goddesses, nymphs are generally regarded as personifications of nature, are ty ...

Tyrus were walking along the beach when Heracles' dog, who was accompanying them, devoured a murex snail and gained a beautiful purple color around its mouth. Tyrus told Heracles she would never accept him as her lover until he gave her a robe of that same colour. So Heracles gathered many murex shells, extracted the dye from them, and dyed the first garment of the colour later called Tyrian purple

Tyrian purple ( grc, πορφύρα ''porphúra''; la, purpura), also known as Phoenician red, Phoenician purple, royal purple, imperial purple, or imperial dye, is a reddish-purple natural dye. The name Tyrian refers to Tyre, Lebanon. It is ...

. The murex shell appears on the very earliest Tyrian coins and then reappears again on coins in Imperial Roman times.

From the sixth century BCE. onward in Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, where there was strong Phoenician cultural influence on the western side of the island, Melquat was often depicted with Heracles' traditional symbols of a lion skin and club, although it is unclear how strongly this connection between the figures was throughout the rest of Phoenician culture.

Attempts at a synthesis

The paucity of evidence on Melqart has led to debate as to the nature of his cult and his place in the Phoenician pantheon.William F. Albright

William Foxwell Albright (May 24, 1891– September 19, 1971) was an American archaeologist, biblical scholar, philologist, and expert on ceramics. He is considered "one of the twentieth century's most influential American biblical scholars."

...

suggested he was a god of the underworld partly because the god Malku, who may be Melqart, is sometimes equated with the Mesopotamian god Nergal

Nergal ( Sumerian: d''KIŠ.UNU'' or ; ; Aramaic: ܢܸܪܓܲܠ; la, Nirgal) was a Mesopotamian god worshiped through all periods of Mesopotamian history, from Early Dynastic to Neo-Babylonian times, with a few attestations under indicating hi ...

, a god of the underworld, whose name also means 'King of the City'.''Archaeology and the Religion of Israel'' (Baltimore, 1953; pp. 81, 196) Others take this to be coincidental, since what is known about Melqart from other sources does not suggest an underworld god, and the city in question could conceivably be Tyre. It has been suggested that Melqart began as a sea god who was later given solar attributes, or alternatively that he began as a solar god who later received the attributes of a sea god.

See also

* For information on the title Ba‘al which was applied to many gods who would not normally be identified with Melqart seeBa‘al

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity. From its use among people, it came to be applied to ...

.

* For views about whether and how Melqart connects with biblical references to Moloch, see Moloch

Moloch (; ''Mōleḵ'' or הַמֹּלֶךְ ''hamMōleḵ''; grc, Μόλοχ, la, Moloch; also Molech or Molek) is a name or a term which appears in the Hebrew Bible several times, primarily in the book of Leviticus. The Bible strongly co ...

.

* For views about whether and how Melqart connects with the names of God in Islam, see Malek

References

Citations

Bibliography

* Bonnet, Corinne, ''Melqart: Cultes et mythes de l'Héraclès tyrien en Méditerranée'' (Leuven and Namur) 1988. The standard summary of the evidences. * .External links

Melqart - World History Encyclopedia

a circumstantial review that gives a good sketch of Aubet's book, in which Melqart figures strongly; Aubet concentrates on Tyre and its colonies and ends, ca 550 BCE, with the rise of Carthage.

L'iconographie de Melqart (article in PDF eng.)

{{Authority control West Semitic gods Tutelary deities Deities in the Hebrew Bible Phoenician mythology Hellenistic Asian deities Heracles Baal