Mellismo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mellismo () was a political practice of Spanish ultra-

Mellismo () was a political practice of Spanish ultra-

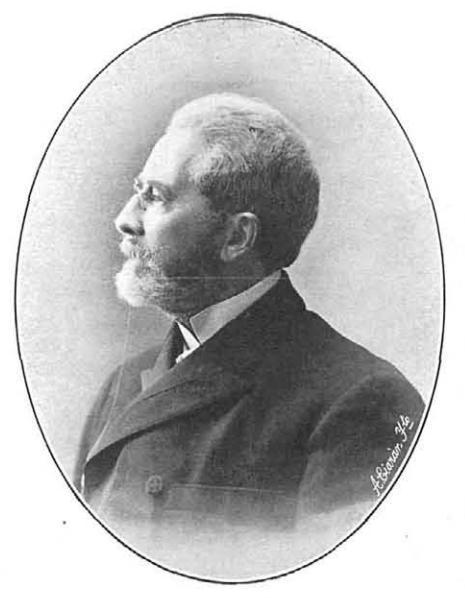

Generally historiographical works do not refer to Mellismo or to Mellistas prior to 1910; press of the era started to use this term as late as 1919. When discussing internal groupings within Carlism in the early years of the 20th century, scholars refer to the faction more inclined towards alliances with other parties as "posibilistas", while those tending to side with a deposed leader marqués de Cerralbo are dubbed "cerralbistas"; this is also how Vázquez de Mella preferred to refer to himself. However, he started to gain supporters and admirers of his own already in the 1890s, initially lured by his charismatic oratory skills rather than by his theoretical vision or specific political strategy. In fact, his stand might have seemed puzzling: he declared himself enemy of the Restoration system but advocated political alliances with established parties, enthusiastically took part in electoral game but was engaged in conspiracy to stage military coup in 1898–1900, supported minimalist electoral coalitions but preached maximalist objectives, claimed doctrinal Traditionalist orthodoxy but remained in uneasy relationship with the king and revealed cautious penchant towards non-dynastical solutions.

After " La Octubrada", a series of minor Carlist 1900 revolts, Mella sought refuge in

Generally historiographical works do not refer to Mellismo or to Mellistas prior to 1910; press of the era started to use this term as late as 1919. When discussing internal groupings within Carlism in the early years of the 20th century, scholars refer to the faction more inclined towards alliances with other parties as "posibilistas", while those tending to side with a deposed leader marqués de Cerralbo are dubbed "cerralbistas"; this is also how Vázquez de Mella preferred to refer to himself. However, he started to gain supporters and admirers of his own already in the 1890s, initially lured by his charismatic oratory skills rather than by his theoretical vision or specific political strategy. In fact, his stand might have seemed puzzling: he declared himself enemy of the Restoration system but advocated political alliances with established parties, enthusiastically took part in electoral game but was engaged in conspiracy to stage military coup in 1898–1900, supported minimalist electoral coalitions but preached maximalist objectives, claimed doctrinal Traditionalist orthodoxy but remained in uneasy relationship with the king and revealed cautious penchant towards non-dynastical solutions.

After " La Octubrada", a series of minor Carlist 1900 revolts, Mella sought refuge in  Following death of Carlos VII his son as the new Carlist king Jaime III found himself pressed by the Cerralbistas to dismiss Feliú; he opted for a compromise, confirming the nomination but appointing Mella as his own personal secretary. After few months the two spent together in 1910 Vázquez de Mella ceased, disillusioned – rather mutually – with his new monarch. During the Cortes campaign of 1910 Mellismo first emerged as a strategy: while Feliú authorized local accords strictly conditioned by dynastic claims, Vázquez de Mella mounted an anti-revolutionary, ultra-conservative, Catholic coalition with

Following death of Carlos VII his son as the new Carlist king Jaime III found himself pressed by the Cerralbistas to dismiss Feliú; he opted for a compromise, confirming the nomination but appointing Mella as his own personal secretary. After few months the two spent together in 1910 Vázquez de Mella ceased, disillusioned – rather mutually – with his new monarch. During the Cortes campaign of 1910 Mellismo first emerged as a strategy: while Feliú authorized local accords strictly conditioned by dynastic claims, Vázquez de Mella mounted an anti-revolutionary, ultra-conservative, Catholic coalition with

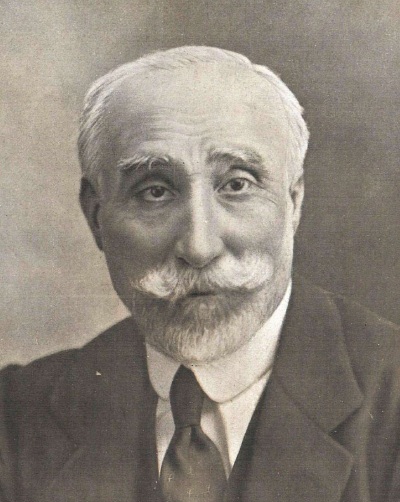

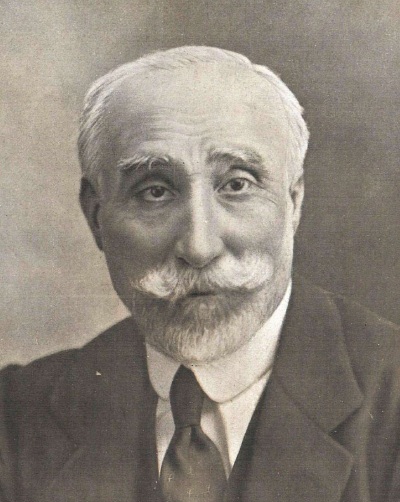

Some scholars claim that with de Cerralbo increasingly fascinated by Vázquez de Mella though also aging, tired of conflict and irresolute, the latter assumed actual command of party structures, while Carlist policy was increasingly formed by Mellismo. The parliamentarian contingent was clearly dominated by Vázquez de Mella's personality; nearly half of its members were Mellistas anyway, the other ones mostly vacillating and only Feliú and Llorens prepared to take a decisive stand. In the 30-member party top body, Junta Superior, around one third were leaning towards Mellismo, including regional jefes of Vascongadas,

Some scholars claim that with de Cerralbo increasingly fascinated by Vázquez de Mella though also aging, tired of conflict and irresolute, the latter assumed actual command of party structures, while Carlist policy was increasingly formed by Mellismo. The parliamentarian contingent was clearly dominated by Vázquez de Mella's personality; nearly half of its members were Mellistas anyway, the other ones mostly vacillating and only Feliú and Llorens prepared to take a decisive stand. In the 30-member party top body, Junta Superior, around one third were leaning towards Mellismo, including regional jefes of Vascongadas,  Following outbreak of the Great War earlier demonstrated pro-German Mellist sympathies turned into a full-blown campaign. Though booklets or lectures technically supported Spanish neutrality, they raised sentiment favoring

Following outbreak of the Great War earlier demonstrated pro-German Mellist sympathies turned into a full-blown campaign. Though booklets or lectures technically supported Spanish neutrality, they raised sentiment favoring

In 1918 Mellismo seemed to have been losing ground: electoral alliances failed to produce major gains, course of the Great War made pro-German attitude pointless and undermined position of its advocates, some regional jefaturas kept voicing dissent and de Cerralbo, increasingly tired of his own double-loyalty, finally managed to get his resignation accepted, temporarily replaced by another Mellista,

In 1918 Mellismo seemed to have been losing ground: electoral alliances failed to produce major gains, course of the Great War made pro-German attitude pointless and undermined position of its advocates, some regional jefaturas kept voicing dissent and de Cerralbo, increasingly tired of his own double-loyalty, finally managed to get his resignation accepted, temporarily replaced by another Mellista,  Many Carlist deputies and senators of the early 20th century turned Mellados: apart from Vázquez de Mella also Luis Garcia Guijarro, Dalmacio Iglesias Garcia, José Ampuero y del Rio, Cesáreo Sanz Escartín, Ignacio Gonzales de Careaga and Víctor Pradera Larumbe; among regional leaders the key to be mentioned were Tirso de Olazábal, José María Juaristi, marqués de Valde-Espina and

Many Carlist deputies and senators of the early 20th century turned Mellados: apart from Vázquez de Mella also Luis Garcia Guijarro, Dalmacio Iglesias Garcia, José Ampuero y del Rio, Cesáreo Sanz Escartín, Ignacio Gonzales de Careaga and Víctor Pradera Larumbe; among regional leaders the key to be mentioned were Tirso de Olazábal, José María Juaristi, marqués de Valde-Espina and

During 1919 the Mellistas were busy institutionalizing the movement. Its backbone were local Centros de Acción Tradicionalista, emergent throughout the country; in

During 1919 the Mellistas were busy institutionalizing the movement. Its backbone were local Centros de Acción Tradicionalista, emergent throughout the country; in  In late 1920 it was already clear that Mellismo is stalled, failing to gain ground on national political scene and getting increasingly paralyzed by two competing strategies. While Vázquez de Mella stuck to his plan of grand extreme-Right federation, at least partially committed to maximalist Traditionalist vision, Pradera emerged as champion of another concept, namely that alliance should be concluded on a minimalist basis, the lowest common denominator having been conservative anti-revolutionary Catholicism. Furthermore, Vázquez de Mella pursued an anti-system and non-dynastical strategy, at best ready to support an acceptable government from the outside, while Pradera was prepared to work within the Restoration Alfonsist framework and to accept jobs in governmental structures. Mellismo suffered another blow when many of its followers joined Partido Social Popular. In 1921 Vázquez de Mella was already in doubt as to launching an own party and seemed pondering upon his role of an ideological pundit providing guidance from the back seat.

In late 1920 it was already clear that Mellismo is stalled, failing to gain ground on national political scene and getting increasingly paralyzed by two competing strategies. While Vázquez de Mella stuck to his plan of grand extreme-Right federation, at least partially committed to maximalist Traditionalist vision, Pradera emerged as champion of another concept, namely that alliance should be concluded on a minimalist basis, the lowest common denominator having been conservative anti-revolutionary Catholicism. Furthermore, Vázquez de Mella pursued an anti-system and non-dynastical strategy, at best ready to support an acceptable government from the outside, while Pradera was prepared to work within the Restoration Alfonsist framework and to accept jobs in governmental structures. Mellismo suffered another blow when many of its followers joined Partido Social Popular. In 1921 Vázquez de Mella was already in doubt as to launching an own party and seemed pondering upon his role of an ideological pundit providing guidance from the back seat.

The long overdue grand Mellist assembly eventually materialized in October 1922 in

The long overdue grand Mellist assembly eventually materialized in October 1922 in

Theoretical work of Mella served as point of reference for generations and was studied far beyond Spain, from

Theoretical work of Mella served as point of reference for generations and was studied far beyond Spain, from

present-day Anglophobiapresent-day Germanophobia

* {{Conservatism Carlism Catholicism and far-right politics Far-right politics in Spain Political movements in Spain

Right

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical ...

of the early 20th century. Born within Carlism, it was designed and championed by Juan Vázquez de Mella, who became its independent political leader after the 1919 breakup. The strategy consisted of an attempt to build a grand ultra-Right party, which in turn would ensure transition from liberal democracy of Restauración to corporative

Corporatism is a Collectivism and individualism, collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by Corporate group (sociology), corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guil ...

Traditionalist monarchy. Following secession from Carlism Mellismo assumed formal shape of Partido Católico-Tradicionalista, but it failed as an amalgamating force and decomposed shortly afterwards. Theoretical vision of Mella is usually considered part of the Carlist concept and does not count as Mellismo; the strategy to achieve it does. In historiography its followers are usually referred to as Mellistas, though initially the term Mellados seemed to prevail. Occasionally they are also named Tradicionalistas, but the term is extremely ambiguous and might denote also other concepts.

Mellismo nascent (1900–1912)

Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and remained there for a few years, estranged also by the claimant who officially dubbed those involved traitors. Having obtained royal pardon in 1903 he resumed parliamentarian career in 1905. As Carlist leaders were usually in their 60s or older, Vázquez de Mella emerged as the most dynamic representative of mid-age generation and most charismatic Carlist politician at all, as a theorist presiding over general overhaul of Carlism. His position consolidated mostly thanks to harangues delivered both in the Cortes

Cortes, Cortés, Cortês, Corts, or Cortès may refer to:

People

* Cortes (surname), including a list of people with the name

** Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), a Spanish conquistador

Places

* Cortes, Navarre, a village in the South border of ...

and at public gatherings; he did not hold official party positions except in its press tribune, ''El Correo Español

''El Correo'' (; ) is a leading daily newspaper in Bilbao and the Basque Country of northern Spain. It is among best-selling general interest newspapers in Spain.

History and profile

The brothers Ybarra y de la Revilla – Fernando, Gabriel and ...

''. His personal prestige soon became sort of a problem for both the claimant and the then political leader, Matías Barrio y Mier, appointed to keep the Cerralbistas in check. On orders of Carlos VII Barrio pursued cautious policy of electoral alliances, confronting possibilist vision of malmenorismo-guided coalitions and trying to curb Vázquez de Mella's influence in ''Correo''. As one of his last political decisions in 1909 the claimant appointed a relatively unknown academic, Bartolomé Feliú y Pérez, as successor of the ailing Barrio; the decision came as a blow to supporters of de Mella, considering him obvious candidate for leadership.

Antonio Maura

Antonio Maura Montaner (2 May 1853 – 13 December 1925) was Prime Minister of Spain on five separate occasions.

Early life

Maura was born in Palma, on the island of Mallorca, and studied law in Madrid. In 1878, Maura married Constanc ...

and his faction of the Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

. During the next 2 years the group already dubbed Mellistas sabotaged Jefe Delegado, their campaign directed against Feliú as incompetent leader and steering clear of the alliance question. In 1912 Mella accused Feliú of illegitimately holding the jefatura and demanded his deposition, threatening the claimant with rejecting his rule as deprived of "legitimacy of execution". Don Jaime gave in and by the end of 1912 he re-appointed de Cerralbo as president of Junta Superior.

In full swing (1912–1919)

Some scholars claim that with de Cerralbo increasingly fascinated by Vázquez de Mella though also aging, tired of conflict and irresolute, the latter assumed actual command of party structures, while Carlist policy was increasingly formed by Mellismo. The parliamentarian contingent was clearly dominated by Vázquez de Mella's personality; nearly half of its members were Mellistas anyway, the other ones mostly vacillating and only Feliú and Llorens prepared to take a decisive stand. In the 30-member party top body, Junta Superior, around one third were leaning towards Mellismo, including regional jefes of Vascongadas,

Some scholars claim that with de Cerralbo increasingly fascinated by Vázquez de Mella though also aging, tired of conflict and irresolute, the latter assumed actual command of party structures, while Carlist policy was increasingly formed by Mellismo. The parliamentarian contingent was clearly dominated by Vázquez de Mella's personality; nearly half of its members were Mellistas anyway, the other ones mostly vacillating and only Feliú and Llorens prepared to take a decisive stand. In the 30-member party top body, Junta Superior, around one third were leaning towards Mellismo, including regional jefes of Vascongadas, Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a '' nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the nort ...

and Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the autonomous community of Valencia and the third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is also the capital of the province of the same name. The wider urban area al ...

. As de Cerralbo re-organized the national executive forming 10 dedicated sections, Mella monopolized the ones of propaganda and press while other Mellistas dominated in electoral and organization ones. ''El Correo Español'' kept having been a battlefield with Don Jaime struggling to retain his influence, but it was getting increasingly dominated by Mellistas, especially Peñaflor.

With Don Jaime hardly contactable in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

following outbreak of the Great War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the Mellistas took almost full control of the party; the Carlist Cortes campaigns of 1914

This year saw the beginning of what became known as World War I, after Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the Austrian throne was Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, assassinated by Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip. It als ...

, 1916

Events

Below, the events of the First World War have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 1 – The British Royal Army Medical Corps carries out the first successful blood transfusion, using blood that had been stored and cooled.

* ...

and 1918

This year is noted for the end of the First World War, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, as well as for the Spanish flu pandemic that killed 50–100 million people worldwide.

Events

Below, the events ...

were visibly marked by Mellista-nurtured long-term strategy. With dramatically declining turnover at the polls and growing fragmentation of two partidos turnistas, it was becoming evident that political system of Restauración was crumbling. Mella nurtured a plan for minimalist alliance of the Right, leading in turn to emergence of a maximalist ultra-Right party, possibly a new incarnation of Traditionalism. That formation was supposed to do away with liberal democracy – a strategy dubbed by some scholars as "catastrofismo" – and ensure passage to Traditionalist, corporative system, with dynastical question parked in obscurity. Though in 1914 provincial jefes were largely left free to conclude any electoral alliances that might produce best possible results, Vázquez de Mella and Maura kept working that they took form of Carlist-Maurist accords. During the 1916 campaign Vázquez de Mella for the first time explicitly referred to a future union of extrema derecha, new terms like "mauro-mellistas", "mauro-jaimistas" or "carlomauristas" entered into circulation and Maura started to make vague anti-system references of altering "ambiente de la vida pública". The strategy, however, demonstrated its limitations. Alliances did not outlive electoral campaigns; Jaimist candidates kept winning around 10 mandates, hardly an impressive improvement compared to the 1890s or 1900s; finally, in regions with strong local identity some party militants grumbled that fuerismo might suffer in a hypothetical ultra-Right alliance.

Following outbreak of the Great War earlier demonstrated pro-German Mellist sympathies turned into a full-blown campaign. Though booklets or lectures technically supported Spanish neutrality, they raised sentiment favoring

Following outbreak of the Great War earlier demonstrated pro-German Mellist sympathies turned into a full-blown campaign. Though booklets or lectures technically supported Spanish neutrality, they raised sentiment favoring Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in ...

and aimed against Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

. After 1916, when pro- Entente feelings were gaining strength, the focus of Mellistas shifted to preventing a would-be Spanish joining the Allies. The claimant, during most of the war unreachable in his Austrian residence, remained ambiguous; officially he supported neutrality, in private leaning towards Entente and sending notes not disavowing pro-German tones of the Mellistas. Scholars differ as to how the World War One issue related to Mellismo. Very few consider it central and even reduce the outlook to pro-German stance. Most suggest that it stemmed from ideological Mellista vision, quote passages praising anti-Liberal German regime and lambasting Masonic

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to Fraternity, fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of Stonemasonry, stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their inte ...

, democratic, parliamentarian British and French systems. Some comments suggest that victory of the Central Powers was expected to facilitate takeover of Spanish political scene by extreme Right, while there are students who suggest that the war issue was of no relevance at all.

1919 breakup

Cesáreo Sanz Escartín

Romualdo Cesáreo Sanz Escartín (1844-1923) was a Spanish Carlist politician and military leader. He is known mostly as a longtime Cortes Generales, Cortes member, first as a deputy and later as a senator, in both cases representing Navarre. In ...

. In early 1919 the claimant was released from his house arrest in Austria, arrived in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

and after 2 years of almost total silence came out with 2 manifestos. In somewhat unclear circumstances published in early February in ''Correo Español'', they explicitly denounced disobedience of unnamed Carlist leaders failing to sustain neutral policy and indicated that command structures of the party would be re-organized.

The Mellistas concluded that the strategy employed previously in struggle for domination in the party – cornering the claimant to elicit his conformity – would no longer work and that an ultimate all-out confrontation was imminent. They mounted a media counter-offensive, going public with charges disseminated privately in 1912 and presenting Don Jaime as a ruler who lost his legitimacy: for years he remained passive and inactive, pursued hypocritical policy declaring neutrality but in fact supporting Entente, departed from Catholic orthodoxy, ignored traditional Carlist collegial bodies embarking on Cesarist policy, toyed with the party and – clear reference to his lack of offspring – behaved irresponsibly; all in all, his latest moves were nothing but a "Jaimada", a coup within and against Traditionalism. None of the conflicting parties referred to the question of political strategy as to the point of contention.

Though initially it might have appeared that the strengths of both sides were comparable, Don Jaime soon tilted the balance in his favor. His men reclaimed control over ''El Correo Español'' and he replaced San Escartín with former germanophile politicians who seemed pro-Mellistas but turned loyal to the royal house, first Pascual Comín and then Luis Hernando de Larramendi. When Alfonsist and Liberal press cheered anticipated demise of conflict-ridden Carlism, many party members earlier demonstrating unease about Don Jaime started to have second thoughts. Vázquez de Mella, conscious of his strong position among MPs and local jefes, responded with a call to stage a grand assembly. Though he explicitly referred to Carlism and Traditionalism, some scholars claim that at that point he already acknowledged that the struggle to control Jaimist structures was pointless; they interpret this appeal as decision to walk out and build a new party. The showdown lasted no longer than two weeks. By the end of February 1919 the Mellistas opted for an own organization, setting Centro de Acción Tradicionalista as their temporary headquarters in Madrid.

Many Carlist deputies and senators of the early 20th century turned Mellados: apart from Vázquez de Mella also Luis Garcia Guijarro, Dalmacio Iglesias Garcia, José Ampuero y del Rio, Cesáreo Sanz Escartín, Ignacio Gonzales de Careaga and Víctor Pradera Larumbe; among regional leaders the key to be mentioned were Tirso de Olazábal, José María Juaristi, marqués de Valde-Espina and

Many Carlist deputies and senators of the early 20th century turned Mellados: apart from Vázquez de Mella also Luis Garcia Guijarro, Dalmacio Iglesias Garcia, José Ampuero y del Rio, Cesáreo Sanz Escartín, Ignacio Gonzales de Careaga and Víctor Pradera Larumbe; among regional leaders the key to be mentioned were Tirso de Olazábal, José María Juaristi, marqués de Valde-Espina and Luis

Luis is a given name. It is the Spanish form of the originally Germanic name or . Other Iberian Romance languages have comparable forms: (with an accent mark on the i) in Portuguese and Galician, in Aragonese and Catalan, while is archaic ...

and Manuel Lezama Leguizamón (Vascongadas), Antonio Mazarrasa (Alava), Doña Marina and Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

(New Castile), Teodoro de Mas, Miguel Salellas Ferrer, Tomas Boada Borrell and duque de Solferino (Catalonia), Manuel Simó Marín and Jaime Chicharro Sánchez-Guió

Jaime Chicharro Sánchez-Guió (1889–1934) was a Spanish Conservative and Carlist politician. He is known mostly as the moving spirit behind turning a fishing bay in Burriana into a modern port, facilitating export of oranges grown in the area. ...

(Valencia) and José Díez de la Cortina (Andalusia); the group was completed by two prolific journalists, Miguel Fernández (Peñaflor) and Claro Abanades Lopez. Most of the breakaways came from 2 regions: Vascongadas (especially Gipuzkoa

Gipuzkoa (, , ; es, Guipúzcoa ; french: Guipuscoa) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the autonomous community of the Basque Country. Its capital city is Donostia-San Sebastián. Gipuzkoa shares borders with the French depa ...

) and Catalonia. Some of regional Jaimist dailies adhered to Mella, though the most important ones, ''El Correo Español'', '' El Pensamiento Navarro'' and '' El Correo Catalán'', stood by the claimant. The impact on the rank-and-file was far less material. In regions where Carlism was a minor force, like Old Castile

Old Castile ( es, Castilla la Vieja ) is a historic region of Spain, which had different definitions along the centuries. Its extension was formally defined in the 1833 territorial division of Spain as the sum of the following provinces: San ...

or Valencia, the breakup added to confusion and further marginalisation of the movement, but in Vascongadas, Navarre

Navarre (; es, Navarra ; eu, Nafarroa ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre ( es, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, links=no ; eu, Nafarroako Foru Komunitatea, links=no ), is a foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, ...

and Catalonia the rural social base of Carlism remained mostly intact.

Reformatting and crisis (1919–1922)

During 1919 the Mellistas were busy institutionalizing the movement. Its backbone were local Centros de Acción Tradicionalista, emergent throughout the country; in

During 1919 the Mellistas were busy institutionalizing the movement. Its backbone were local Centros de Acción Tradicionalista, emergent throughout the country; in Madrid

Madrid ( , ) is the capital and most populous city of Spain. The city has almost 3.4 million inhabitants and a metropolitan area population of approximately 6.7 million. It is the second-largest city in the European Union (EU), and ...

'' El Pensamiento Español'' was set up as the national press tribune and there were also attempts to build an affiliated youth and shirt organization, Juventudes y Requetés Tradicionalistas. Though Mella rejected a ministerial post in a new government of national unity, claiming he could never align himself with the 1876 constitution and its system, in May Mellismo assumed shape of Centro Católico Tradicionalista, set up before the 1919 elections and intended as a stepping stone towards an ultra-Right alliance dominated by the Traditionalists. Not constrained by dynastic Carlist bounds any more though rejecting also the Alfonsist monarchy as corrupted by Liberalism, CCT was an attempt to use Catholic platform to lure right-wing offshoots from the Conservative Party, mostly the Mauristas

Maurism (''Maurismo'' in Spanish) was a conservative political movement that bloomed in Spain from 1913 around the political figure of Antonio Maura after a schism in the Conservative Party between ''idóneos'' ('apt ones') and ''mauristas'' ('maur ...

and the Ciervistas. Other potential alliances reported were those with the Integrists and Unión Monárquica Nacional. The elections produced 4 mandates; Mella himself failed to gain a ticket.

Since the summer of 1919 the Mellistas started to gear up for a grand Asamblea Nacional, supposed to launch a new party and set its political course; though "Católico Nacional" was considered as the party name, it eventually materialized as Partido Católico-Tradicionalista. Regional Mellista gatherings were staged in the Biscay

Biscay (; eu, Bizkaia ; es, Vizcaya ) is a province of Spain and a historical territory of the Basque Country, heir of the ancient Lordship of Biscay, lying on the south shore of the eponymous bay. The capital and largest city is Bilbao.

B ...

Archanda (August 1919) and in the Catalan Badalona

Badalona (, , , ) is a Municipalities of Spain, municipality to the immediate north east of Barcelona in Catalonia, Spain. It is located on the left bank of the Besòs River and on the Mediterranean Sea, in the Barcelona metropolitan area. By popu ...

(April 1920). However, as the new 1920 electoral campaign unfolded it was getting evident that like before, different groupings of the Right were ready to conclude circumstantial deals, but none was willing to enter integration path towards a new party of ultra derecha. Different Mellista personalities were getting inclined to pursue alliance talks on their own, usually purely pragmatic basis: some like Pradera negotiated with the Mauristas, some like Chicharro talked to the Ciervistas, some were approaching the social-Catholic initiative of former Vázquez de Mella sympathizers Aznar and Minguijón and some neared a monarchist Catholic idea advocated by ''El Debate

''El Debate'' is a defunct Spanish Catholic daily newspaper, published in Madrid between 1910 and 1936. It was the most important Catholic newspaper of its time in Spain.

History and profile

''El Debate'' was founded in 1910 by Guillermo de Rivas ...

''. The elections produced mere 2 Mellista mandates; Vázquez de Mella, who lost again, soon launched his bid for seat in Tribunal Supremo, but failed to mount sufficient support among conservative parties and suffered prestigious defeat.

In late 1920 it was already clear that Mellismo is stalled, failing to gain ground on national political scene and getting increasingly paralyzed by two competing strategies. While Vázquez de Mella stuck to his plan of grand extreme-Right federation, at least partially committed to maximalist Traditionalist vision, Pradera emerged as champion of another concept, namely that alliance should be concluded on a minimalist basis, the lowest common denominator having been conservative anti-revolutionary Catholicism. Furthermore, Vázquez de Mella pursued an anti-system and non-dynastical strategy, at best ready to support an acceptable government from the outside, while Pradera was prepared to work within the Restoration Alfonsist framework and to accept jobs in governmental structures. Mellismo suffered another blow when many of its followers joined Partido Social Popular. In 1921 Vázquez de Mella was already in doubt as to launching an own party and seemed pondering upon his role of an ideological pundit providing guidance from the back seat.

In late 1920 it was already clear that Mellismo is stalled, failing to gain ground on national political scene and getting increasingly paralyzed by two competing strategies. While Vázquez de Mella stuck to his plan of grand extreme-Right federation, at least partially committed to maximalist Traditionalist vision, Pradera emerged as champion of another concept, namely that alliance should be concluded on a minimalist basis, the lowest common denominator having been conservative anti-revolutionary Catholicism. Furthermore, Vázquez de Mella pursued an anti-system and non-dynastical strategy, at best ready to support an acceptable government from the outside, while Pradera was prepared to work within the Restoration Alfonsist framework and to accept jobs in governmental structures. Mellismo suffered another blow when many of its followers joined Partido Social Popular. In 1921 Vázquez de Mella was already in doubt as to launching an own party and seemed pondering upon his role of an ideological pundit providing guidance from the back seat.

Demise (1922 and after)

The long overdue grand Mellist assembly eventually materialized in October 1922 in

The long overdue grand Mellist assembly eventually materialized in October 1922 in Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

, though it was anything but what Vázquez de Mella had originally intended. Many Mellistas who broke with Don Jaime almost 4 years earlier had departed for other political initiatives in the meantime, others lost enthusiasm following 2 unsuccessful electoral campaigns and disillusioned by the movement having been stuck with apparent loss of direction, little progress on path towards a Rightist alliance and Vázquez de Mella increasingly withdrawing into long periods of inactivity. The gathering was dominated by the Praderistas and Vázquez de Mella himself did not attend; instead he sent a letter, boiling down to his political last will. Once again reasserting his anti-system views he confirmed Traditionalist monarchy as an ultimate goal and declared himself committed to work towards it as theorist and ideologue, though not as a politician any more. Members of the presidency acknowledged the letter and politely declared themselves looking forward to reversal of Vázquez de Mella's decision; the assembly ended in favor of setting up a new Catholic party.

The Zaragoza assembly was effectively the funeral of Mellismo, even though in the last Restauración elections of 1923 there were two candidates successfully running on the Catholic-Traditionalist ticket. During almost a year following the Zaragoza meeting further Vázquez de Mella followers joined other political initiatives. In 1923 national party life came to a standstill once Primo de Rivera Primo de Rivera is a Spanish family prominent in politics of the 19th and 20th centuries:

*Fernando Primo de Rivera (1831–1921), Spanish politician and soldier

*Miguel Primo de Rivera (1870–1930), nephew of Fernando, military officer and dictat ...

dictatorship was declared and all political organizations were dissolved; likewise, Partido Católico-Tradicionalista ceased to exist. Some Mellistas engaged in primoderiverista structures: few of them assumed high administrative positions and Pradera emerged even as dictatorship's iconic figure, but scholars do not agree whether that activity had anything to do with Mellismo. There are students who claim that Mellistas "headed by Pradera" engaged in Unión Patriotica and reconciled with the Alfonsine monarchy, pointing to gradual demise of the group only after the Vázquez de Mella's death. Other authors consider Mellismo defunct as political grouping and at best refer to "seudotradicionalismo" or "mellistas praderistas", underlining only loose association with original "mellismo ortodoxo". Some dub the co-operative strategy “Praderismo” and note that co-operation with the Primo regime, deprived of any ideological backbone let alone a Traditionalist one, had little to do with Mellism.

Vázquez de Mella withdrew into privacy; his last public appearance was in 1924 and he died in 1928. In 1931-1932 many former Vázquez de Mella followers re-united with mainstream Carlism joining Comunión Tradicionalista; this is probably the last moment to which some historians apply the term Mellists, though others are more cautious and prefer to refer to post-mellistas. Within the Comunión structures the former Mellists did not form any visible grouping or faction, though there are scholars who claim that during the Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII, and was di ...

and the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

some of the Mellist-Jaimist divisions got reproduced as a pattern. In non-scholarly public dispute the term "mellistas" is at times used in most arbitrary and whimsical circumstances, e.g. to denote pro-Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

Spaniards of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Reception and legacy

Theoretical work of Mella served as point of reference for generations and was studied far beyond Spain, from

Theoretical work of Mella served as point of reference for generations and was studied far beyond Spain, from Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

or the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

to Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

. However, it is universally approached as intrinsic part of Traditionalist doctrine, not infrequently presented as its most refined, in-depth, and systematic component, in fact the climax of Traditionalist political philosophy. The term "Mellismo" is not applied to it, used only as reference to political strategy pursued by Vázquez de Mella and his followers; as such, it generated far lesser interest.

In historiography until the late 20th century the Mellistas were acknowledged mostly in works dealing with different dimensions of Carlism. The authors tended to focus on the 1919 breakup, sometimes portrayed as another one in long history of ruptures in the movement; the secession was presented as resulting either from clash of personalities or from conflicting views on Spanish stand during the First World War. It was the first major monograph, published in 2000, which systematically re-defined Mellismo as a strategy to build an ultra-Right formation leading the transition from liberal democracy of late Restauración to corporative Traditionalist monarchy. According to this theory, the grouping envisaged was supposed to consist of three tiers: complete amalgamation based on common program, federation with those who accepted it partially, and circumstantial co-operation with other groups.

Apart from origins of the 1919 rupture, there are questions pertaining to other issues which remain unanswered. It is not clear whether Mella intended to take over Carlism by reducing the claimant to a decorative role or whether he consciously aimed at a secession. It remains to be traced how a question of foreign policy, usually of secondary importance for most political parties, managed to trigger a schism, especially given in 1919 the war was over and Carlism has always demonstrated little interest, if not indeed contempt, for anything beyond the borders of Spain. One may ask how come that Mellism was potent enough to devastate one of the oldest European political movements but it proved entirely ineffective as a project on its own. There are questions pertaining to the time frame, namely whether Vázquez de Mella's grip on Carlism prior to 1919 and co-operation with primoderiverista institutions after 1923 count as Mellismo. Explanation is yet to be provided as to motives of personalities who were iconic for their loyalty to Carlist kings, but decided to join the Mellistas, like it was the case of Tirso Olazábal."la posición de los notables no fue tan clara, Tirso Olazábal que se encontraba retirado de la vida pública, fue un ejemplo de notable local fiel al rey; sin embargo, su actitud le llevó esta vez a secundar a Vázquez de Mella. Guipuzcoanos, Vizcaínos y Catalanes fueron los que en mayoría formaron las huestes mellistas", Orella Martínez 2012, pp. 182–3

See also

*Anglophobia

Anti-English sentiment or Anglophobia (from Latin ''Anglus'' "English" and Greek φόβος, ''phobos'', "fear") means opposition to, dislike of, fear of, hatred of, or the oppression and persecution of England and/or English people.''Oxford ...

* Carlism

* Electoral Carlism (Restoration)

Electoral Carlism of Restoration was vital to sustain Traditionalism in the period between the Third Carlist War and the Primo de Rivera dictatorship. Carlism, defeated in 1876, during the Restauración period recalibrated its focus from militar ...

* Jaime, Duke of Madrid

Jaime de Borbón y de Borbón-Parma, known as Duke of Madrid and as Jacques de Bourbon, Duke of Anjou in France (27 June 1870 – 2 October 1931), was the Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain under the name Jaime III and the Legitimist c ...

* Juan Vázquez de Mella

Footnotes

Further reading

* Francisco Javier Alonso Vázquez, ''El siglo futuro, El correo español y Vázquez de Mella en sus invectivas a la masonería ante el desastre del 98'', n:J. A. Ferrer Benimeli (ed.), ''La masonería española y la crisis colonial del 98'', vol. 2, Barcelona, 1999, pp. 503–525 * Luis Aguirre Prado, ''Vázquez de Mella'', Madrid 1959 * Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, ''El caso Feliú y el dominio de Mella en el partido carlista en el período 1909–1912'', n:''Historia contemporánea'' 10 (1997), pp. 99–116 * Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, ''El cisma mellista. Historia de una ambición política'', Madrid 2000, * Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, ''El control mellista del órgano carlista oficial. "El Correo Español" antes de la Gran Guerra'', n:''Aportes'' 40/2 (1999), pp. 67–78 * Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, ''Precedentes del proyecto ultraderechista mellista en el periodo 1900-1912'', n:''Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia'' 202/1 (2005), pp. 119–134 * Jacek Bartyzel, ''Synteza doktrynalna: Vázquez de Mella'', n:Jacek Bartyzel, ''Umierać ale powoli'', Kraków 2002, , pp. 276–285 * Jacek Bartyzel, ''Tradycjonalistyczna wizja regionalizmu Juana Vazqueza de Melli'', n:Jacek Bartyzel, ''Nic bez Boga, nic wbrew tradycji'', Radzymin 2015, , pp. 189–201 * Boyd D. Cathey, ''Juan Vázquez de Mella and the Transformation of Spanish Carlism, 1885-1936'', n:Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, John Radzilowski (eds.), ''Spanish Carlism and Polish Nationalism: The Borderlands of Europe in the 19th and 20th Centuries'', Charlottesville 2003, * Agustín Fernández Escudero, ''El marqués de Cerralbo (1845-1922): biografía politica'' hD thesis Madrid 2012 * Agustín Fernández Escudero, ''El marqués de Cerralbo. Una vida entre el carlismo y la arqueología'', Madrid 2015, * José María García Escudero, ''El pensamiento de El Debate: un diario católico en la crisis de España (1911-1936)'', Madrid 1983, * Pedro Carlos Gonzales Cuevas, ''El pensamiento socio-político de la derecha maurista'', n:''Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia'' 190/3 (1993), pp. 365–426 * Juan María Guasch Borrat, ''El Debate y la crisis de la Restauración 1910-1923'', Pamplona 1986, * José Javier López Antón, ''Trayectoria ideológica del carlismo bajo don Jaime III, 1909-1931'', n:''Aportes'' 15 (1990), pp. 36–50 * Osvaldo Lira, ''Nostalgía de Vázquez de Mella'', Buenos Aires 2007, * Raimundo de Miguel López, ''La política tradicionalista para D. Juan Vázquez de Mella'', Sevilla 1982 * Raimundo de Miguel López, ''Liberalismo y tradicionalismo para don Juan Vázquez de Mella'', Sevilla 1980 * Maria Cruz Mina Apat, ''La escisión carlista de 1919 y la unión de las derechas'', n:J. J. Garcia Delgado (ed.), ''La crisis de la Restauración. España entre la primera guerra mundial y la II República'', Madrid 1986, , pp. 149–164 * Jaime Lluis Navas, ''Las divisones internas del carlismo a través de su historia: ensayo sobre su razón de ser (1814-1936)'', n:Juan Maluquer de Motes y Nicolau (ed.), ''Homenajes a Jaime Vicens Vives'', vol. 2, Barcelona 1967, pp. 307–345 * José Luis Orella Martínez, ''Consecuencias de la Gran Guerra Mundial en el abanico político español'', n:''Aportes'' 84 (2014), pp. 105–134 * José Luis Orella Martínez, ''El origen del primer católicismo social español'' hD thesis UNED Madrid 2012 * José Luis Orella Martínez, ''Víctor Pradera: Un católico en la vida pública de principios de siglo'', Madrid 2000, * José Luis Orella Martínez, ''Víctor Pradera y la derecha católica española'' hD thesis Deusto Bilbao 1995 * Manuel Rodríguez Carrajo, ''Vázquez de Mella, sobre su vida y su obra'', n:''Estudios'' 29 (1973), pp. 525–673 * Francisco Sevilla Benito, ''Sociedad y regionalismo en Vázquez de Mella. La sistematización doctrinal del carlismo'', Madrid 2009,External links

*present-day Anglophobia

* {{Conservatism Carlism Catholicism and far-right politics Far-right politics in Spain Political movements in Spain