Meir Dizengoff on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Meir Dizengoff ( he, מֵאִיר דִּיזֶנְגּוֹף, russian: Меер Янкелевич Дизенгоф ''Meer Yankelevich Dizengof'', 25 February 1861 – 23 September 1936) was a

In Kishinev Dizengoff met

In Kishinev Dizengoff met

Dizengoff was one of the founders of the Ahuzat Bayit Company, organized to establish a modern Jewish quarter near the Arab city of

Dizengoff was one of the founders of the Ahuzat Bayit Company, organized to establish a modern Jewish quarter near the Arab city of

Dizengoff was consequently involved with the development of the city, and encouraged its rapid expansion—carrying out daily inspections, and paying attention to details such as entertainment. He was always present at the head of the ''

Dizengoff was consequently involved with the development of the city, and encouraged its rapid expansion—carrying out daily inspections, and paying attention to details such as entertainment. He was always present at the head of the ''

Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

leader and politician and the founder and first mayor of Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

(1911-1922 as head of town planning, 1922-1936 as mayor). Dizengoff's actions in Ottoman Palestine

Ottoman Syria ( ar, سوريا العثمانية) refers to divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of Syria, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Arabian Desert and south ...

and the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. The manda ...

helped lead to the creation of the State of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the name ...

declared Israeli independence in 1948 at Dizengoff's residence in Tel Aviv. Dizengoff House is now Israel's Independence Hall

Independence Hall is a historic civic building in Philadelphia, where both the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were debated and adopted by America's Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Fa ...

.

Early life

Meir Dizengoff was born on Shushan Purim, 25 February 1861 in the village of Ekimovtsy nearOrhei

Orhei (; Yiddish ''Uriv'' – אוריװ), also formerly known as Orgeev (russian: Орге́ев), is a city, municipality and the administrative centre of Orhei District in the Moldova, Republic of Moldova, with a population of 21,065. Orhei ...

, Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Be ...

. In 1878, his family moved to Kishinev, where he graduated from high school and studied at the polytechnic school. In 1882, he volunteered in the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

, serving in Zhytomyr

Zhytomyr ( uk, Жито́мир, translit=Zhytomyr ; russian: Жито́мир, Zhitomir ; pl, Żytomierz ; yi, זשיטאָמיר, Zhitomir; german: Schytomyr ) is a city in the north of the western half of Ukraine. It is the Capital city, a ...

(now in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

) until 1884. There he first met , whom he married in the early 1890s. After his military service, Dizengoff remained in Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, where he became involved in the ''Narodnaya Volya

Narodnaya Volya ( rus, Наро́дная во́ля, p=nɐˈrodnəjə ˈvolʲə, t=People's Will) was a late 19th-century revolutionary political organization in the Russian Empire which conducted assassinations of government officials in an att ...

'' underground. In 1885, he was arrested for insurgency and spent 8 months in jail. In Odessa, he met Leon Pinsker

yi, לעאָן פינסקער

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Tomaszów Lubelski, Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = Odessa, Russian Empire

, known_for = Zionism

, occupation = Physician, political activ ...

, Ahad Ha’am and others, and joined the Hovevei Zion

Hovevei Zion ( he, חובבי ציון, lit. ''hose who areLovers of Zion''), also known as Hibbat Zion ( he, חיבת ציון), refers to a variety of organizations which were founded in 1881 in response to the Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian ...

movement. Upon his release from prison, Dizengoff returned to Kishinev and founded the Bessarabian branch of Hovevei Zion, which he represented at the 1887 conference. He left Kishinev in 1888 to study chemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials int ...

at the Sorbonne

Sorbonne may refer to:

* Sorbonne (building), historic building in Paris, which housed the University of Paris and is now shared among multiple universities.

*the University of Paris (c. 1150 – 1970)

*one of its components or linked institution, ...

in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. At the Sorbonne he met Elie Scheid, a representative of Baron Edmond de Rothschild

Baron Abraham Edmond Benjamin James de Rothschild (Hebrew: הברון אברהם אדמונד בנימין ג'יימס רוטשילד - ''HaBaron Avraham Edmond Binyamin Ya'akov Rotshield''; 19 August 1845 – 2 November 1934) was a French memb ...

's projects in Ottoman Palestine

Ottoman Syria ( ar, سوريا العثمانية) refers to divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of Syria, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Arabian Desert and south ...

.

Zionist leadership

In Kishinev Dizengoff met

In Kishinev Dizengoff met Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern p ...

and became an ardent follower. However, Dizengoff strongly opposed the British Uganda Scheme

The Uganda Scheme was a proposal presented at the Sixth World Zionist Congress in Basel in 1903 by Zionism founder Theodor Herzl to create a Jewish homeland in a portion of British East Africa. He presented it as a temporary refuge for Jews to ...

promoted by Herzl at the Sixth Zionist Congress

The Sixth Zionist Congress was held in Basel, opening on August 23, 1903. Theodor Herzl caused great division amongst the delegates when he presented the " Uganda Scheme", a proposed Jewish colony in what is now part of Kenya. Herzl died the follo ...

. Instead, Dizengoff favored the formation of Jewish communities in Palestine. Dizengoff became actively involved in land purchases and establishment of Jewish communities, most notably Tel Aviv.

Dizengoff was widely regarded as a leader of the Jewish community prior to the establishment of the State of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. Many notable world leaders who traveled to Ottoman Palestine

Ottoman Syria ( ar, سوريا العثمانية) refers to divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of Syria, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Arabian Desert and south ...

and the British Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. The manda ...

met with Meir Dizengoff as a representative of the Jewish community.

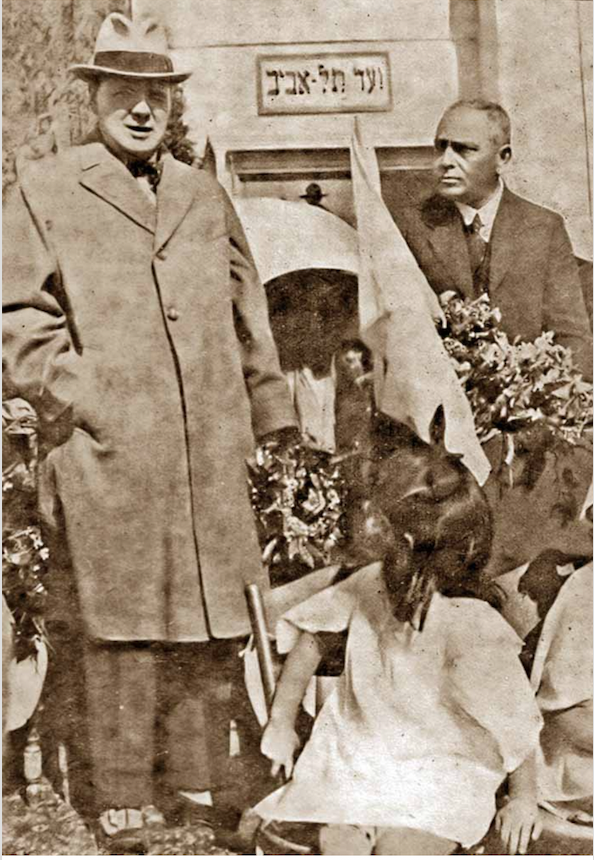

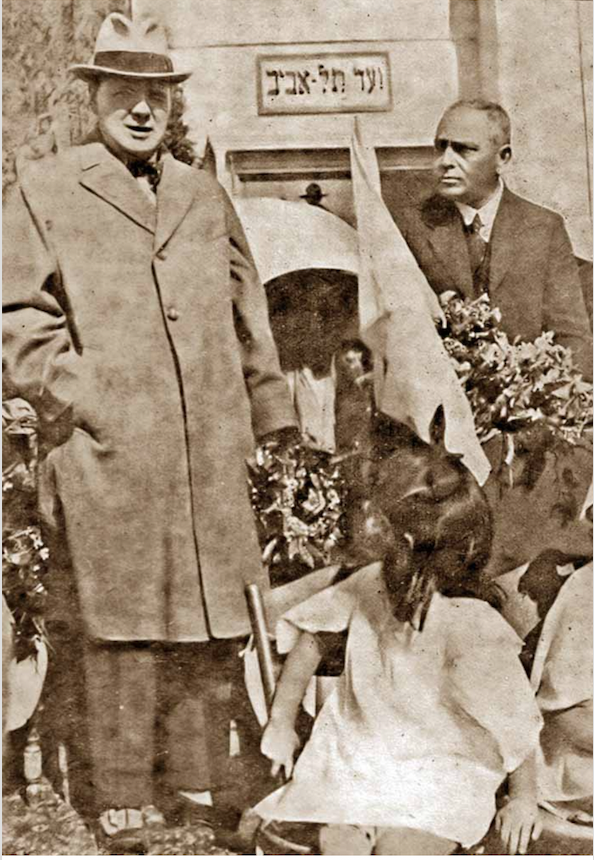

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

visited Palestine in March 1921 and met with Dizengoff. During a ceremonial speech with Churchill, Dizengoff declared: “this small town of Tel-Aviv, which is hardly 12 years old, has been conquered by us on sand dunes, and we have built it with our work and our exertions.” Churchill was impressed with the motivation and determination of the pioneers, under the leadership of Dizengoff. In Palestine, Churchill told an anti-Zionist delegation: “This country has been very much neglected in the past and starved and even mutilated by Turkish misgovernment… you can see with your own eyes in many parts of this country the work which has already been done by Jewish colonies; how sandy wastes have been reclaimed and thriving farms and orangeries planted in their stead.” That same day he told a Jewish delegation he would inform London that the Zionists are “transforming waste into fertile..planting trees and developing agriculture in desert lands...making for an increase in wealth and cultivation" and further that the Arab population is “deriving great benefit, sharing in the general improvement and advancement.”

Business ventures

While studyingchemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials int ...

at the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

, Dizengoff met Edmond James de Rothschild

Baron Abraham Edmond Benjamin James de Rothschild (Hebrew: הברון אברהם אדמונד בנימין ג'יימס רוטשילד - ''HaBaron Avraham Edmond Binyamin Ya'akov Rotshield''; 19 August 1845 – 2 November 1934) was a French memb ...

, who sent him to Ottoman-ruled Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

to establish a glass factory

Glass is a non-crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling (quenching) of ...

which would supply bottles for Rothschild's wineries. Dizengoff opened the factory in Tantura

Tantura ( ar, الطنطورة, ''al-Tantura'', lit. ''The Peak''; Hebrew and Phoenician: דור, ''Dor'') was a Palestinian Arab fishing village located northwest of Zikhron Ya'akov on the Mediterranean coast of Israel. Near the village, lies ...

in 1892, but it proved unsuccessful due to impurities in the sand, and Dizengoff soon returned to Kishinev.

In 1905, spurred by his Zionist beliefs, Dizengoff returned to Palestine and settled in Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

. He established the ''Geulah'' company, which bought up land in Palestine from Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

, and became involved in the import

An import is the receiving country in an export from the sending country. Importation and exportation are the defining financial transactions of international trade.

In international trade, the importation and exportation of goods are limited ...

business, especially machinery and automobiles to replace the horse-drawn carriages that had served as the primary transportation from Jaffa port to Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

and other towns. He also co-founded a boat company that bore his name, and served as the Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

.

When Dizengoff learned that residents were organizing to build a new neighborhood, Tel Aviv, he formed a partnership with the ''Ahuzat Bayit

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the ...

'' company and bought land on the outskirts of Jaffa, which was parceled out to the early settlers by lot.

Founding of Tel Aviv

Dizengoff was one of the founders of the Ahuzat Bayit Company, organized to establish a modern Jewish quarter near the Arab city of

Dizengoff was one of the founders of the Ahuzat Bayit Company, organized to establish a modern Jewish quarter near the Arab city of Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

in 1909.

On April 11, 1909, sixty-six families gathered on the sandy shoreline to divide up lots of what was to become Tel Aviv. Meir Dizengoff, the civic leader who would be the city's first mayor, participated in the lottery. The moment was captured on film by Abraham Suskind. In the iconic image, members of the collective can be seen standing on sand dunes in the exact location where Rothschild Boulevard

Rothschild Boulevard (, ''Sderot Rotshild'') is one of the principal streets in the center of Tel Aviv, Israel, beginning in Neve Tzedek at its southwestern edge and running north to Habima Theatre. It is one of the most expensive streets in the c ...

currently runs. According to legend, the man standing behind the group, on the slope of the sand dune, is a man who opposed the idea, allegedly telling the others that they are mad because there is no water at the location.

Mayor of Tel Aviv

Dizengoff and his wife were among the first sixty-six families who gathered on 11 April 1909 on a sand dune north of Jaffa to hold a lottery to distribute plots of land which established what eventually became the city of Tel Aviv. Dizengoff became head of the town planning in 1911, a position that he held until 1922. When Tel Aviv was recognized as a city, Dizengoff was elected mayor. He remained in office until shortly before his death, apart from a three-year hiatus in 1925–1928. DuringWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the Ottomans drove out a large part of the population and Dizengoff was the liaison between the exiles and the Ottoman authorities. In this position he dealt with aid sent to the exiles of Tel Aviv and received the nickname '' Reish Galuta''. He widely circulated and publicized the plight of the exiles, mainly via newspapers, and succeeded in convincing the rulers to agree to a regular supply of food and provisions to the exiles. In 1917, after having received funding from Nili

NILI was a Jewish espionage network which assisted the United Kingdom in its fight against the Ottoman Empire in Palestine between 1915 and 1917, during World War I. NILI is an acronym which stands for the Hebrew phrase "Netzah Yisrael Lo Yesha ...

, Dizengoff refused not only to provide funds to free Nili member Yosef Lishansky

Yosef Lishansky ( he, יוסף לישנסקי; 1890 – 16 December 1917) was a Jewish paramilitary and a spy for the British in Ottoman Palestine. Upon his arrival in Palestine, Lishansky sought to join HaShomer but, denied membership, ...

, but even funds to provide the succor that Dizengoff provided other prisoners and even anti-Zionists, despite having received the money from Nili.

Right after the Arab riots of April–May 1921, he persuaded the authorities of the British Mandate to recognize Tel Aviv as an independent municipality and not a part of Jaffa. In the early 1920s Dizengoff was able to entice several cultural icons to live in Tel Aviv. After Asher Zvi Greenberg, known as Ahad Ha-Am

Asher Zvi Hirsch Ginsberg (18 August 1856 – 2 January 1927), primarily known by his Hebrew name and pen name Ahad Ha'am ( he, אחד העם, lit. 'one of the people', Genesis 26:10), was a Hebrew essayist, and one of the foremost pre-state Zi ...

, arrived in Israel in 1922, Dizengoff offered him a teaching position at Tel Aviv's first Hebrew-speaking high school, Herzliya Gymnasium

The Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium ( he, הַגִּימְנַסְיָה הָעִבְרִית הֶרְצְלִיָּה, ''HaGymnasia HaIvrit Herzliya'', Also known as ''Gymnasia Herzliya''), originally known as HaGymnasia HaIvrit (lit. Hebrew High Scho ...

. Although Greenberg was living in Jerusalem at the time, the offer of a job, and a house on the newly named Ahad ha-Am Street, convinced the Zionist philosopher to move to Tel Aviv. The poet Hayim Nahman Bialik

Hayim Nahman Bialik ( he, חיים נחמן ביאַליק; January 9, 1873 – July 4, 1934), was a Jewish poet who wrote primarily in Hebrew but also in Yiddish. Bialik was one of the pioneers of modern Hebrew poetry. He was part of the vangu ...

also decided not to move to Jerusalem due to Dizengoff's offer of a house, a job and a street named after him if he moved to Tel Aviv, which he did in 1924. The artist Reuven Rubin

Reuven Rubin ( he, ראובן רובין; November 13, 1893 – October 13, 1974) was a Romanian-born Israeli painter and Israel's first ambassador to Romania.

Biography

Rubin Zelicovici (later Reuven Rubin) was born in Galaţi to a poor Roma ...

also was persuaded by Dizengoff to move to Tel Aviv.

Many committees and associations came into being during Dizengoff's term as mayor. One was the Levant Fair

The Levant Fair (Hebrew: יריד המזרח; Yarid HaMizrach) was an international trade fair held in Tel Aviv during the 1920s and 1930s.

History

Early years

One of the early precursors to the Levant Fair, an exhibition titled the "Exhibiti ...

(Hebrew ''Yarid HaMizrah'') committee, founded in 1932, which organized its first fair that year. Initially, the fair was held in the south of the city, but after its great success, a fairground with designated buildings was built in north Tel Aviv. A large international fair was held in 1934, followed by a second fair two years later.

Dizengoff was consequently involved with the development of the city, and encouraged its rapid expansion—carrying out daily inspections, and paying attention to details such as entertainment. He was always present at the head of the ''

Dizengoff was consequently involved with the development of the city, and encouraged its rapid expansion—carrying out daily inspections, and paying attention to details such as entertainment. He was always present at the head of the ''Adloyada

Adloyada (Hebrew: , lit. "Until one no longer knows") is a humorous procession held in Israel on the Jewish holiday of Purim (or in Shushan Purim the second day of Purim, commanded to be celebrated in "walled cities", nowadays only in Jerusal ...

'', the annual Purim

Purim (; , ; see Name below) is a Jewish holiday which commemorates the saving of the Jews, Jewish people from Haman, an official of the Achaemenid Empire who was planning to have all of Persia's Jewish subjects killed, as recounted in the Boo ...

carnival

Carnival is a Catholic Christian festive season that occurs before the liturgical season of Lent. The main events typically occur during February or early March, during the period historically known as Shrovetide (or Pre-Lent). Carnival typi ...

. After his wife's death, he donated his house to the city of Tel Aviv, for use as an art museum, and he influenced many important artists to donate their work to improve the museum.

In 1936, with the outbreak of the Arab revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, الثورة العربية الكبرى, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On t ...

, the Arabs closed the port of Jaffa with the intention of halting the rapid expansion of Jewish settlements in Mandatory Palestine. Dizengoff pressured the government to give him permission to open a port in his new city of Tel Aviv, and before his death he managed to dedicate the first pier of Tel Aviv's new port. His dedication began with the words: "Ladies and gentlemen, I can still remember the day when Tel Aviv had no port".

After years of building houses, hospitals, public institutions, a synagogue, etc. Dizengoff wrote “we began to feel the need to foster beauty”. On a visit to Paris, Dizengoff created an artistic committee. Marc Chagall

Marc Chagall; russian: link=no, Марк Заха́рович Шага́л ; be, Марк Захаравіч Шагал . (born Moishe Shagal; 28 March 1985) was a Russian-French artist. An early modernism, modernist, he was associated with se ...

wrote: “Mr. Dizengoff came to me in Paris, asking for help in building a museum. I couldn’t believe the man was seventy years old, his eyes sparkled…though I intended several times to go to the Land of Israel, and every time I cancelled the trip- this time, Mr. Dizengoff’s enthusiasm influenced me.. I packed my things and decided to give him a hand.”

In June 1931, Marc Chagall and his family traveled to Tel Aviv, on the invitation of Dizengoff, in conjunction with his plan to build a Jewish Museum in the new city. They were invited to stay at Dizengoff's house in Tel Aviv.

Dizengoff House / Independence Hall

In 1930, after the death of his wife, Dizengoff donated his house to his beloved city of Tel Aviv and requested that it be turned into a museum. The house underwent extensive renovations and became theTel Aviv Museum of Art

Tel Aviv Museum of Art ( he, מוזיאון תל אביב לאמנות ''Muzeon Tel Aviv Leomanut'') is an art museum in Tel Aviv, Israel. The museum is dedicated to the preservation and display of modern and contemporary art from Israel and aroun ...

in 1932. The museum moved to its current location in 1971. On 14 May 1948, David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the name ...

declared the independence of the State of Israel at the Dizengoff residence. The building is now a history museum and known as Independence Hall.

There is a monument at Dizengoff House (Independence Hall) honoring both the 66 original families of Tel Aviv as well as a statue of Dizengoff riding his famous horse.

Death

Dizengoff died on September 23, 1936. He is buried in theTrumpeldor Cemetery

Trumpeldor Cemetery ( he, בית הקברות טרומפלדור), often referred to as the "Old Cemetery," is a historic cemetery on Trumpeldor Street in Tel Aviv, Israel. The cemetery covers 10.6 acres, and contains approximately 5,000 graves. ...

in Tel Aviv.

Commemoration

Meir Park andDizengoff Street

Dizengoff Street ( he, רחוב דיזנגוף, ''Rehov Dizengoff'') is a major street in central Tel Aviv, named after Tel Aviv's first mayor, Meir Dizengoff.

The street runs from the corner of Ibn Gabirol Street in its southernmost point to the ...

are named after him. His name also lives on in Israeli slang: It was used as a verb—''lehizdangeff''—which means "to walk down Dizengoff," i.e., go out on the town. Dizengoff Square

Dizengoff Square or Dizengoff Circus ( he, כִּכָּר דִיזֶנְגוֹף, fully Zina Dizengoff Square, , ''Kikar Tsina Dizengof'') is an iconicYaacov Agam

Yaacov Agam ( he, יעקב אגם) (born 11 May 1928) is an Israeli sculptor and experimental artist widely known for his contributions to optical and kinetic art.

Biography

Yaacov Gibstein (later Agam) was born in Israel, which, at that time ...

, is named after his wife, Zina.

References

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Dizengoff, Meir 1861 births 1936 deaths People from Orhei District Jews from the Russian Empire Emigrants from the Russian Empire to the Ottoman Empire Jewish mayors Jewish National Council members Jews in Mandatory Palestine Members of the Assembly of Representatives (Mandatory Palestine) Mayors of Tel Aviv-Yafo Narodnaya Volya Jewish socialists University of Paris alumni Burials at Trumpeldor Cemetery Expatriates from the Russian Empire in France