Medical leech on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Hirudo medicinalis'', the European medicinal leech, is one of several

Their range extends over almost the whole of

Their range extends over almost the whole of

The first description of leech therapy, classified as

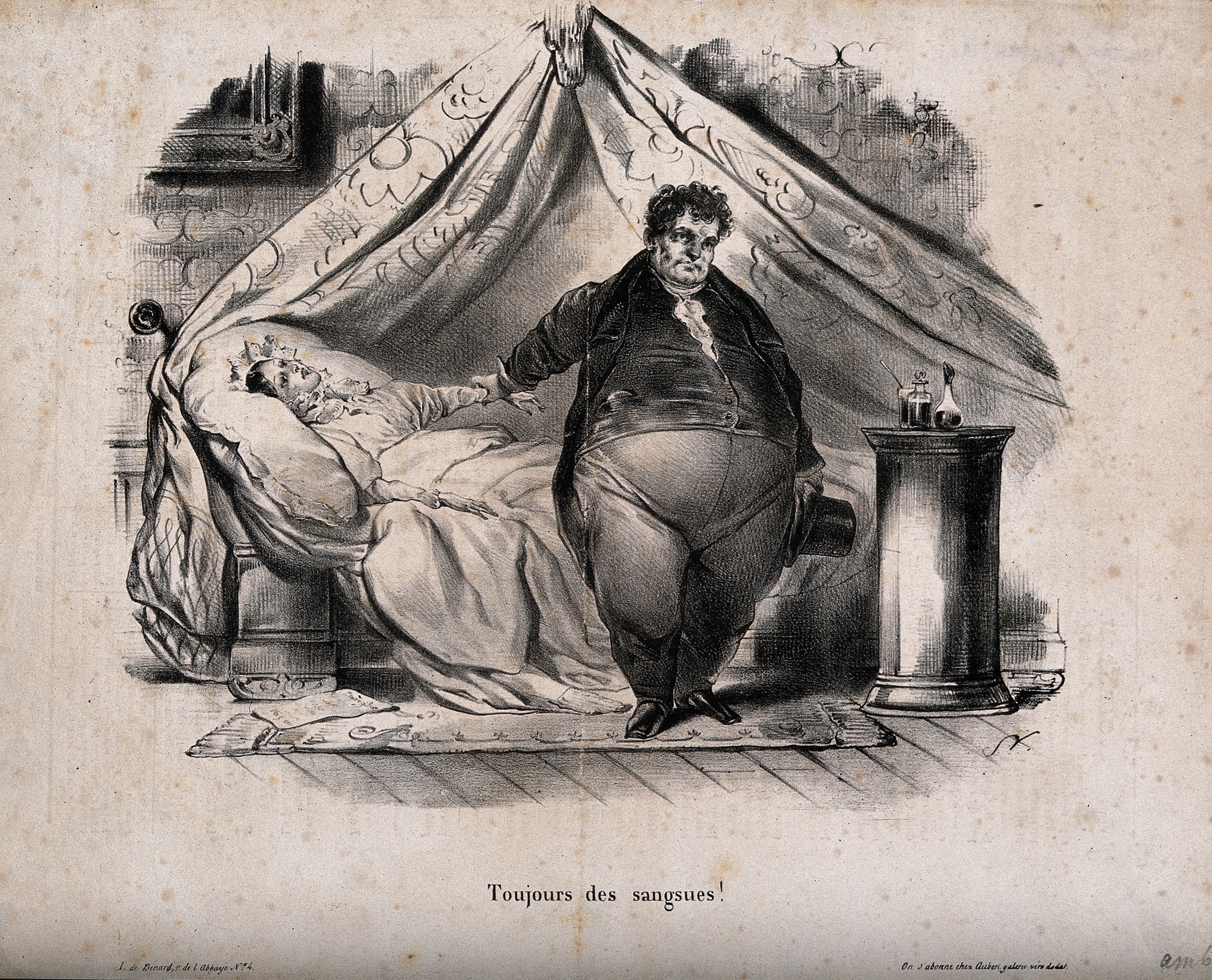

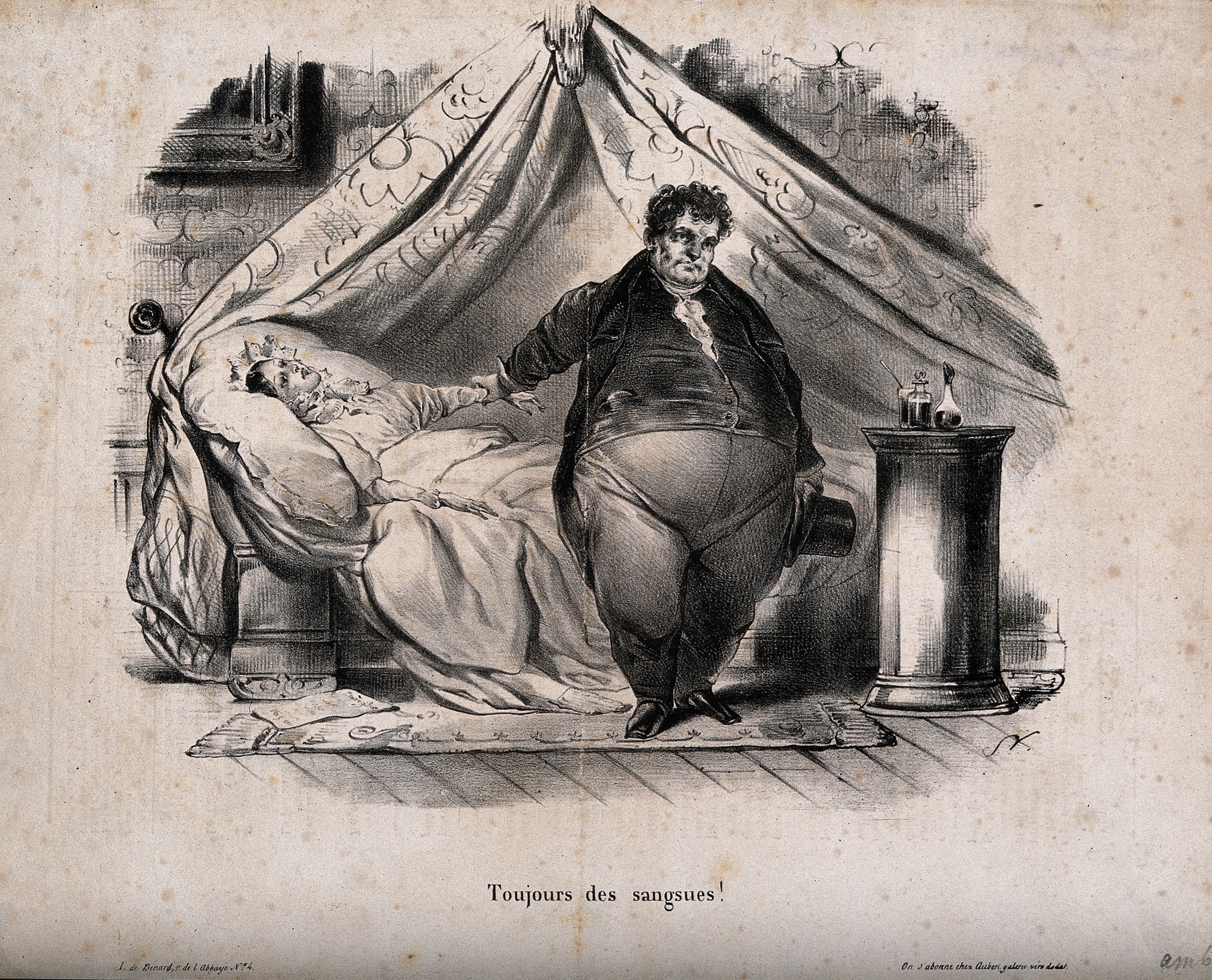

The first description of leech therapy, classified as  In medieval and early modern medicine, the medicinal leech (''Hirudo medicinalis'' and its congeners ''H. verbana'', ''H. troctina'', and ''H. orientalis'') was used to remove blood from a patient as part of a process to balance the

In medieval and early modern medicine, the medicinal leech (''Hirudo medicinalis'' and its congeners ''H. verbana'', ''H. troctina'', and ''H. orientalis'') was used to remove blood from a patient as part of a process to balance the

Taxonomy page

in

Documentary about alternative medicine with leeches and maggots

* ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yP_7yDlCMG8 Video footage of the unique Bedale Leech Housebr>Leeches eshop

in Lodeksa with many excellent references {{Taxonbar, from=Q30041 Animals described in 1758 Biologically-based therapies Leeches Plastic surgery Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Traditional medicine

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of leeches

Leeches are segmented parasitism, parasitic or Predation, predatory worms that comprise the Class (biology), subclass Hirudinea within the phylum Annelida. They are closely related to the Oligochaeta, oligochaetes, which include the earthwor ...

used as "medicinal leeches".

Other species of ''Hirudo

''Hirudo'' is a genus of leeches of the family Hirudinidae. It was described by Carl Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus (; 23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after his ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné Blunt (2004), p. 171. (), was a ...

'' sometimes also used as medicinal leeches include '' H. orientalis'', ''H. troctina'', and '' H. verbana''. The Asian medicinal leech includes '' Hirudinaria manillensis'', and the North American medicinal leech is '' Macrobdella decora''.

Morphology

The generalmorphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

of medicinal leeches follows that of most other leeches. Fully mature adults can be up to 20 cm in length, and are green, brown, or greenish-brown with a darker tone on the dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

* Dorsal co ...

side and a lighter ventral

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek language, Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. Th ...

side. The dorsal side also has a thin red stripe. These organisms have two suckers, one at each end, called the anterior

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

and posterior suckers. The posterior is used mainly for leverage, whereas the anterior sucker, consisting of the jaw

The jaw is any opposable articulated structure at the entrance of the mouth, typically used for grasping and manipulating food. The term ''jaws'' is also broadly applied to the whole of the structures constituting the vault of the mouth and serv ...

and teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, tear ...

, is where the feeding takes place. Medicinal leeches have three jaws (tripartite) that resemble saws, on which are approximately 100 sharp edges used to incise the host. The incision leaves a mark that is an inverted Y inside of a circle. After piercing the skin, they suck out blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells. Blood in the c ...

while injecting anticoagulant

Anticoagulants, commonly known as blood thinners, are chemical substances that prevent or reduce coagulation of blood, prolonging the clotting time. Some of them occur naturally in blood-eating animals such as leeches and mosquitoes, where the ...

s (hirudin

Hirudin is a naturally occurring peptide in the salivary glands of blood-sucking leeches (such as ''Hirudo medicinalis'') that has a blood anticoagulant property. This is fundamental for the leeches’ habit of feeding on blood, since it keeps a h ...

). Large adults can consume up to ten times their body weight in a single meal, with 5–15 mL being the average volume taken. These leeches can live for up to a year between feeding.

Medicinal leeches are hermaphrodite

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrate ...

s that reproduce by sex

Sex is the trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing animal or plant produces male or female gametes. Male plants and animals produce smaller mobile gametes (spermatozoa, sperm, pollen), while females produce larger ones (ova, oft ...

ual mating, laying eggs in clutches of up to 50 near (but not under) water, and in shaded, humid places. A study done in Poland concluded that they have been found inside the nest of large aquatic birds although, their effect on the bird is largely unknown.

Range and ecology

Their range extends over almost the whole of

Their range extends over almost the whole of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

and into Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

as far as Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

and Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked cou ...

. The preferred habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

for this species is muddy freshwater pools and ditches with plentiful weed growth in temperate climates.

Over-exploitation

Overexploitation, also called overharvesting, refers to harvesting a renewable resource to the point of diminishing returns. Continued overexploitation can lead to the destruction of the resource, as it will be unable to replenish. The term app ...

by leech collector

A leech collector, leech gatherer, or leech finder was a person occupied with procuring medicinal leeches, which were in growing demand in 19th-century Europe. Leeches were used in bloodletting but were not easy for medical practitioners to obtai ...

s in the 19th century has left only scattered populations, and reduction in natural habitat through drainage has also contributed to their decline. Another factor has been the replacement of horses

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

in farming

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people to ...

(horses were medicinal leeches' preferred food source) and provision of artificial water supplies for cattle. As a result, this species is now considered near threatened

A near-threatened species is a species which has been categorized as "Near Threatened" (NT) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as that may be vulnerable to endangerment in the near future, but it does not currently qualify fo ...

by the IUCN

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

, and European medicinal leeches are legally protected through nearly all of their natural range. They are particularly sparsely distributed in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, and in the UK there may be as few as 20 remaining isolated populations (all widely scattered). The largest (at Lydd

Lydd is a town and electoral ward in Kent, England, lying on Romney Marsh. It is one of the larger settlements on the marsh, and the most southerly town in Kent. Lydd reached the height of its prosperity during the 13th century, when it was a co ...

) is estimated to contain several thousand individuals; 12 of these areas have been designated Sites of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle of ...

. There are small, transplanted populations in several countries outside their natural range, including the USA.

The species is protected under Appendix II of CITES

CITES (shorter name for the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, also known as the Washington Convention) is a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of interna ...

meaning international trade (including in parts and derivatives) is regulated by the CITES permitting system.

Medical usage

Beneficial secretions

Medicinal leeches have been found to secretesaliva

Saliva (commonly referred to as spit) is an extracellular fluid produced and secreted by salivary glands in the mouth. In humans, saliva is around 99% water, plus electrolytes, mucus, white blood cells, epithelial cells (from which DNA can be ...

containing about 60 different proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

. These achieve a wide variety of goals useful to the leech as it feeds, helping to keep the blood in liquid form and increasing blood flow in the affected area. Several of these secreted proteins serve as anticoagulant

Anticoagulants, commonly known as blood thinners, are chemical substances that prevent or reduce coagulation of blood, prolonging the clotting time. Some of them occur naturally in blood-eating animals such as leeches and mosquitoes, where the ...

s (such as hirudin

Hirudin is a naturally occurring peptide in the salivary glands of blood-sucking leeches (such as ''Hirudo medicinalis'') that has a blood anticoagulant property. This is fundamental for the leeches’ habit of feeding on blood, since it keeps a h ...

), platelet aggregation

Platelets, also called thrombocytes (from Greek θρόμβος, "clot" and κύτος, "cell"), are a component of blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping, thereby ini ...

inhibitors (most notably apyrase

Apyrase (, ''ATP-diphosphatase'', adenosine diphosphatase, ''ADPase'', ''ATP diphosphohydrolase'') is a calcium-activated plasma membrane-bound enzyme (magnesium can also activate it) () that catalyses the hydrolysis of ATP to yield AMP and ino ...

, collagenase

Collagenases are enzymes that break the peptide bonds in collagen. They assist in destroying extracellular structures in the pathogenesis of bacteria such as ''Clostridium''. They are considered a virulence factor, facilitating the spread of ga ...

, and calin), vasodilators

Vasodilation is the widening of blood vessels. It results from relaxation of smooth muscle cells within the vessel walls, in particular in the large veins, large arteries, and smaller arterioles. The process is the opposite of vasoconstriction, ...

, and proteinase

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the for ...

inhibitors. It is also thought that the saliva contains an anesthetic

An anesthetic (American English) or anaesthetic (British English; see spelling differences) is a drug used to induce anesthesia — in other words, to result in a temporary loss of sensation or awareness. They may be divided into two ...

, as leech bites are generally not painful.

Historically

The first description of leech therapy, classified as

The first description of leech therapy, classified as blood letting

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) is the withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and other bodily fl ...

, is found in the ''Sushruta Samhita

The ''Sushruta Samhita'' (सुश्रुतसंहिता, IAST: ''Suśrutasaṃhitā'', literally "Suśruta's Compendium") is an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and surgery, and one of the most important such treatises on this subj ...

'', an ancient Sanskrit medical text. It describes 12 types of leeches (6 venomous and 6 non-venomous).

Diseases where leech therapy was indicated include skin diseases, sciatica

Sciatica is pain going down the leg from the lower back. This pain may go down the back, outside, or front of the leg. Onset is often sudden following activities like heavy lifting, though gradual onset may also occur. The pain is often described ...

, and musculoskeletal pains.

humors

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek medicine, Ancient Greek and Medicine in ancient Rome, Roman physicians and Greek philosoph ...

that, according to Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be one of ...

, must be kept in balance for the human body to function properly. (The four humors of ancient medical philosophy were blood, phlegm

Phlegm (; , ''phlégma'', "inflammation", "humour caused by heat") is mucus produced by the respiratory system, excluding that produced by the nasal passages. It often refers to respiratory mucus expelled by coughing, otherwise known as sputum ...

, black bile

Melancholia or melancholy (from el, µέλαινα χολή ',Burton, Bk. I, p. 147 meaning black bile) is a concept found throughout History of medicine#Greece and Roman Empire, ancient, medieval medicine of Western Europe, medieval and Lear ...

, and yellow bile

Humorism, the humoral theory, or humoralism, was a system of medicine detailing a supposed makeup and workings of the human body, adopted by Ancient Greek and Roman physicians and philosophers.

Humorism began to fall out of favor in the 1850s ...

.) Any sickness that caused the subject's skin to become red (e.g. fever

Fever, also referred to as pyrexia, is defined as having a body temperature, temperature above the human body temperature, normal range due to an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, set point. There is not a single ...

and inflammation), so the theory went, must have arisen from too much blood in the body. Similarly, any person whose behavior was strident and sanguine was thought to be suffering from an excess of blood. Leeches were often gathered by leech collectors and were eventually farmed in large numbers. A unique 19th-century " Leech House" survives in Bedale

Bedale ( ) is a market town and civil parish in the district of Hambleton, North Yorkshire, England. Historically part of the North Riding of Yorkshire, it is north of Leeds, south-west of Middlesbrough and south-west of the county town of ...

, North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is the largest ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county (lieutenancy area) in England, covering an area of . Around 40% of the county is covered by National parks of the United Kingdom, national parks, including most of ...

on the bank of the Bedale Beck, used to store medicinal leeches until the early 20th century.

A recorded use of leeches in medicine was also found during 200 BC by the Greek physician Nicander

Nicander of Colophon ( grc-gre, Νίκανδρος ὁ Κολοφώνιος, Níkandros ho Kolophṓnios; fl. 2nd century BC), Greek poet, physician and grammarian, was born at Claros (Ahmetbeyli in modern Turkey), near Colophon, where his famil ...

in Colophon. Medical use of leeches was discussed by Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

in ''The Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' ( ar, القانون في الطب, italic=yes ''al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb''; fa, قانون در طب, italic=yes, ''Qanun-e dâr Tâb'') is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Persian physician-phi ...

'' (1020s), and by Abd al-Latif al-Baghdadi

ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-Baghdādī ( ar, عبداللطيف البغدادي, 1162 Baghdad–1231 Baghdad), short for Muwaffaq al-Dīn Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Laṭīf ibn Yūsuf al-Baghdādī ( ar, موفق الدين محمد عبد اللطيف بن ...

in the 12th century. The use of leeches began to become less widespread towards the end of the 19th century.

Manchester Royal Infirmary

Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI) is a large NHS teaching hospital in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, England. Founded by Charles White in 1752 as part of the voluntary hospital movement of the 18th century, it is now a major regional and nati ...

used 50,000 leeches a year in 1831. The price of leeches varied between one penny and threepence halfpenny each. In 1832 leeches accounted for 4.4% of the total hospital expenditure. The hospital maintained an aquarium for leeches until the 1930s.

Today

Medicinal leech therapy (also referred to as ''Hirudotherapy'' or ''Hirudin therapy'') made an international comeback in the 1970s inmicrosurgery

Microsurgery is a general term for surgery requiring an operating microscope. The most obvious developments have been procedures developed to allow anastomosis of successively smaller blood vessels and nerves (typically 1 mm in diameter) which ...

, used to stimulate circulation to salvage skin grafts and other tissue threatened by postoperative venous congestion, particularly in finger reattachment and reconstructive surgery

Reconstructive surgery is surgery performed to restore normal appearance and function to body parts malformed by a disease or medical condition.

Description

Reconstructive surgery is a term with training, clinical, and reimbursement implica ...

of the ear, nose, lip, and eyelid. Other clinical applications of medicinal leech therapy include varicose veins

Varicose veins, also known as varicoses, are a medical condition in which superficial veins become enlarged and twisted. These veins typically develop in the legs, just under the skin. Varicose veins usually cause few symptoms. However, some indi ...

, muscle cramps, thrombophlebitis

Thrombophlebitis is a phlebitis (inflammation of a vein) related to a thrombus (blood clot). When it occurs repeatedly in different locations, it is known as thrombophlebitis migrans (migratory thrombophlebitis).

Signs and symptoms

The following s ...

, and osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a type of degenerative joint disease that results from breakdown of joint cartilage and underlying bone which affects 1 in 7 adults in the United States. It is believed to be the fourth leading cause of disability in the w ...

, among many varied conditions. The therapeutic effect is not from the small amount of blood taken in the meal, but from the continued and steady bleeding from the wound left after the leech has detached, as well as the anesthetizing, anti-inflammatory, and vasodilating properties of the secreted leech saliva. The most common complication from leech treatment is prolonged bleeding, which can easily be treated, but more serious allergic reactions and bacterial infections may also occur. Leech therapy was classified by the US Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respon ...

as a medical device in 2004.

Because of the minuscule amounts of hirudin

Hirudin is a naturally occurring peptide in the salivary glands of blood-sucking leeches (such as ''Hirudo medicinalis'') that has a blood anticoagulant property. This is fundamental for the leeches’ habit of feeding on blood, since it keeps a h ...

present in leeches, it is impractical to harvest the substance for widespread medical use. Hirudin (and related substances) are synthesized using recombinant techniques. Devices called "mechanical leeches" that dispense heparin

Heparin, also known as unfractionated heparin (UFH), is a medication and naturally occurring glycosaminoglycan. Since heparins depend on the activity of antithrombin, they are considered anticoagulants. Specifically it is also used in the treatm ...

and perform the same function as medicinal leeches have been developed, but they are not yet commercially available.

See also

*Helminthic therapy

Helminthic therapy, an experimental type of immunotherapy, is the treatment of autoimmune diseases and immune disorders by means of deliberate infestation with a helminth or with the eggs of a helminth. Helminths are parasitic worms such as hoo ...

– other medical use of parasites

*Ichthyotherapy

Ichthyotherapy is the use of fish such as '' Garra rufa'' for cleaning skin wounds or treating other skin conditions. The name ichthyotherapy comes from the Greek name for fish – ichthys. The history of such treatment in traditional medicine is s ...

– medical use of fish

References

External links

Taxonomy page

in

PubMed

PubMed is a free search engine accessing primarily the MEDLINE database of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics. The United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) at the National Institutes of Health maintain the ...

with many excellent referencesDocumentary about alternative medicine with leeches and maggots

* ttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yP_7yDlCMG8 Video footage of the unique Bedale Leech Housebr>Leeches eshop

in Lodeksa with many excellent references {{Taxonbar, from=Q30041 Animals described in 1758 Biologically-based therapies Leeches Plastic surgery Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Traditional medicine