McMahonвҖ“Hussein Correspondence on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The McMahonвҖ“Hussein Correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during

The McMahonвҖ“Hussein Correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during

McMahon's letter to Hussein dated 24 October 1915 declared Britain's willingness to recognize the independence of the Arabs subject to certain exemptions. The original correspondence was conducted in both English and Arabic; slightly differing English translations are extant.

The correspondence was written first in English before being translated to Arabic and vice versa; the identity of the writer and translator is unclear. Kedourie and others assumed the likeliest candidate for primary author is

McMahon's letter to Hussein dated 24 October 1915 declared Britain's willingness to recognize the independence of the Arabs subject to certain exemptions. The original correspondence was conducted in both English and Arabic; slightly differing English translations are extant.

The correspondence was written first in English before being translated to Arabic and vice versa; the identity of the writer and translator is unclear. Kedourie and others assumed the likeliest candidate for primary author is

CAB/24/214, CP 271 (30)

. McMahon described conversations with a

A committee established by the British in 1939 to clarify the arguments said many commitments had been made during and after the war and that all of them would have to be studied together. The Arab representatives submitted a statement from Sir

A committee established by the British in 1939 to clarify the arguments said many commitments had been made during and after the war and that all of them would have to be studied together. The Arab representatives submitted a statement from Sir

pdf version

(0.3 MB)

Original pdf

(7.3MB) * * * * * * * *

The Arabian Peninsula in 1914

Җ”UK National Archives (including information on the HusseinвҖ“McMahon Correspondence) {{DEFAULTSORT:Mcmahon-Hussein Correspondence 1915 documents 1915 in international relations 1915 in Ottoman Syria 1916 documents 1916 in international relations 1916 in Ottoman Syria Arab Revolt Collection of The National Archives (United Kingdom) Correspondences Documents of Mandatory Palestine France in World War I United Kingdom in World War I World War I documents

The McMahonвҖ“Hussein Correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during

The McMahonвҖ“Hussein Correspondence is a series of letters that were exchanged during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

in which the Government of the United Kingdom

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a MhГІrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal coat of arms of t ...

agreed to recognize Arab independence in a large region after the war in exchange for the Sharif of Mecca

The Sharif of Mecca ( ar, ШҙШұЩҠЩҒ Щ…ЩғШ©, SharД«f Makkah) or Hejaz ( ar, ШҙШұЩҠЩҒ Ш§Щ„ШӯШ¬Ш§ШІ, SharД«f al-бёӨijДҒz, links=no) was the title of the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca, traditional steward of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and ...

launching the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, Ш§Щ„Ш«ЩҲШұШ© Ш§Щ„Ш№ШұШЁЩҠШ©, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, Ш§Щ„Ш«ЩҲШұШ© Ш§Щ„Ш№ШұШЁЩҠШ© Ш§Щ„ЩғШЁШұЩү, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

against the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, РһОёПүОјОұОҪО№ОәО® О‘П…П„ОҝОәПҒОұП„ОҝПҒОҜОұ, OthЕҚmanikД“ Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The correspondence had a significant influence on Middle Eastern history during and after the war; a dispute over Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East J ...

continued thereafter.

The correspondence is composed of ten letters that were exchanged from July 1915 to March 1916 between Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca

Hussein bin Ali al-Hashimi ( ar, Ш§Щ„ШӯШіЩҠЩҶ ШЁЩҶ Ш№Щ„ЩҠ Ш§Щ„ЩҮШ§ШҙЩ…ЩҠ, al-бёӨusayn bin вҖҳAlД« al-HДҒshimД«; 1 May 18544 June 1931) was an Arab leader from the Banu Hashim clan who was the Sharif and Emir of Mecca from 1908 and, after procla ...

and Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry McMahon

Sir Arthur Henry McMahon (28 November 1862 вҖ“ 29 December 1949) was a British Indian Army officer and diplomat who served as the High Commissioner in Egypt from 1915 to 1917. He was also an administrator in British India and served twice a ...

, British High Commissioner to Egypt. Whilst there was some military value in the Arab manpower and local knowledge alongside the British Army, the primary reason for the arrangement was to counteract the Ottoman declaration of ''jihad'' ("holy war") against the Allies, and to maintain the support of the 70 million Muslims in British India (particularly those in the Indian Army that had been deployed in all major theatres of the wider war). The area of Arab independence was defined to be "in the limits and boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca

The Sharif of Mecca ( ar, ШҙШұЩҠЩҒ Щ…ЩғШ©, SharД«f Makkah) or Hejaz ( ar, ШҙШұЩҠЩҒ Ш§Щ„ШӯШ¬Ш§ШІ, SharД«f al-бёӨijДҒz, links=no) was the title of the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca, traditional steward of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and ...

" with the exception of "portions of Syria" lying to the west of "the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama

Hama ( ar, ШӯЩҺЩ…ЩҺШ§Ш© ', ; syr, ЬҡЬЎЬ¬, Д§(Йҷ)mЙ‘Оё, lit=fortress; Biblical Hebrew: ''бёӨamДҒб№Ҝ'') is a city on the banks of the Orontes River in west-central Syria. It is located north of Damascus and north of Homs. It is the provinci ...

and Aleppo"; conflicting interpretations of this description were to cause great controversy in subsequent years. One particular dispute, which continues to the present, is the extent of the coastal exclusion.

Following the publication of the November 1917 Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

(a letter written by British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour to Baron Rothschild, a wealthy and prominent leader in the British Jewish community), which promised a national home for the Jews in Palestine, and the subsequent leaking of the secret 1916 SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement

The SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, to define their mutually agreed Sphere of influence, spheres of influence and control in a ...

in which Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and France proposed to split and occupy parts of the territory, the Sharif and other Arab leaders considered the agreements made in the McMahonвҖ“Hussein Correspondence had been violated. Hussein refused to ratify the 1919 Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: TraitГ© de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1 ...

and, in response to a 1921 British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English ...

proposal to sign a treaty accepting the Mandate system, stated that he could not be expected to "affix his name to a document assigning Palestine to the Zionists and Syria to foreigners". A further British attempt to reach a treaty failed in 1923вҖ“24, with negotiations suspended in March 1924; within six months, the British withdrew their support in favour of their central Arabian ally Ibn Saud

Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud ( ar, Ш№ШЁШҜ Ш§Щ„Ш№ШІЩҠШІ ШЁЩҶ Ш№ШЁШҜ Ш§Щ„ШұШӯЩ…ЩҶ ШўЩ„ ШіШ№ЩҲШҜ, КҝAbd al КҝAzД«z bin КҝAbd ar RaбёҘman ДҖl SuКҝЕ«d; 15 January 1875Ibn Saud's birth year has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted ...

, who proceeded to conquer Hussein's kingdom.

The correspondence "haunted Anglo-Arab relations" for many decades thereafter. In January 1923, unofficial excerpts were published by Joseph N. M. Jeffries in the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' and copies of the letters circulated in the Arab press. Excerpts were published in the 1937 Peel Commission Report and the correspondence was published in full in George Antonius

George Habib Antonius, CBE (hon.) ( ar, Ш¬ЩҲШұШ¬ ШӯШЁЩҠШЁ ШЈЩҶШ·ЩҲЩҶЩҠЩҲШі; October 9, 1891May 21, 1942) was a Lebanese author and diplomat who settled in Jerusalem. He was one of the first historians of Arab nationalism. Born in Deir al Qamar ...

's 1938 book ''The Arab Awakening

''The Arab Awakening'' is a 1938 book by George Antonius, published in London by Hamish Hamilton. It is viewed as the foundational textbook of the history of modern Arab nationalism. According to Martin Kramer, ''The Arab Awakening'' "became the p ...

'', then officially in 1939 as '' Cmd. 5957''. Further documents were declassified in 1964.

Background

Initial discussions

The first documented discussions between the UK and theHashemites

The Hashemites ( ar, Ш§Щ„ЩҮШ§ШҙЩ…ЩҠЩҲЩҶ, al-HДҒshimД«yЕ«n), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916вҖ“1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (19 ...

took place in February 1914, five months prior to the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. Discussions were between the Consul-General in Egypt Lord Kitchener Lord Kitchener may refer to:

* Earl Kitchener, for the title

* Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener

Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, (; 24 June 1850 вҖ“ 5 June 1916) was a senior British Army officer and colonial administrator. ...

and Abdullah bin al-Hussein, the second son of Hussein bin Ali

AbЕ« КҝAbd AllДҒh al-бёӨusayn ibn КҝAlД« ibn AbД« ṬДҒlib ( ar, ШЈШЁЩҲ Ш№ШЁШҜ Ш§Щ„Щ„ЩҮ Ш§Щ„ШӯШіЩҠЩҶ ШЁЩҶ Ш№Щ„ЩҠ ШЁЩҶ ШЈШЁЩҠ Ш·Ш§Щ„ШЁ; 10 January 626 вҖ“ 10 October 680) was a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a son of Ali ibn Abi ...

, Sharif of Mecca

The Sharif of Mecca ( ar, ШҙШұЩҠЩҒ Щ…ЩғШ©, SharД«f Makkah) or Hejaz ( ar, ШҙШұЩҠЩҒ Ш§Щ„ШӯШ¬Ш§ШІ, SharД«f al-бёӨijДҒz, links=no) was the title of the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca, traditional steward of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina and ...

. Hussein had grown uncomfortable with the newly appointed Ottoman governor in his Hejaz Vilayet, Wehib Pasha

Wehib Pasha also known as Vehip Pasha, Mehmed Wehib Pasha, Mehmet Vehip Pasha (modern Turkish: ''KaГ§Дұ Vehip PaЕҹa'' or ''Mehmet Vehip (KaГ§Дұ)'', 1877вҖ“1940), was a general in the Ottoman Army. He fought in the Balkan Wars and in several the ...

, reflecting on rising tensions since the 1908 completion of the Hejaz railway, which threatened to support increased Ottoman centralization in the region. Discussions culminated in a telegram sent on 1 November 1914 from KitchenerвҖ”who had recently been appointed as Secretary of WarвҖ”to Hussein wherein Great Britain would, in exchange for support from the Arabs of Hejaz, "...guarantee the independence, rights and privileges of the Sharifate against all external foreign aggression, in particular, that of the Ottomans". The Sharif indicated he could not break with the Ottomans immediately but the entry of the Ottomans on Germany's side in World War I on 11 November 1914 brought about an abrupt shift in British political interests concerning an Arab revolt against the Ottomans. According to historian David Charlwood, the failure in Gallipoli led to an increased desire on the part of the UK to negotiate a deal with the Arabs. Lieshout gives further background on the reasoning behind the shift in British thinking.

Damascus Protocol

On 23 May 1915,Emir

Emir (; ar, ШЈЩ…ЩҠШұ ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cer ...

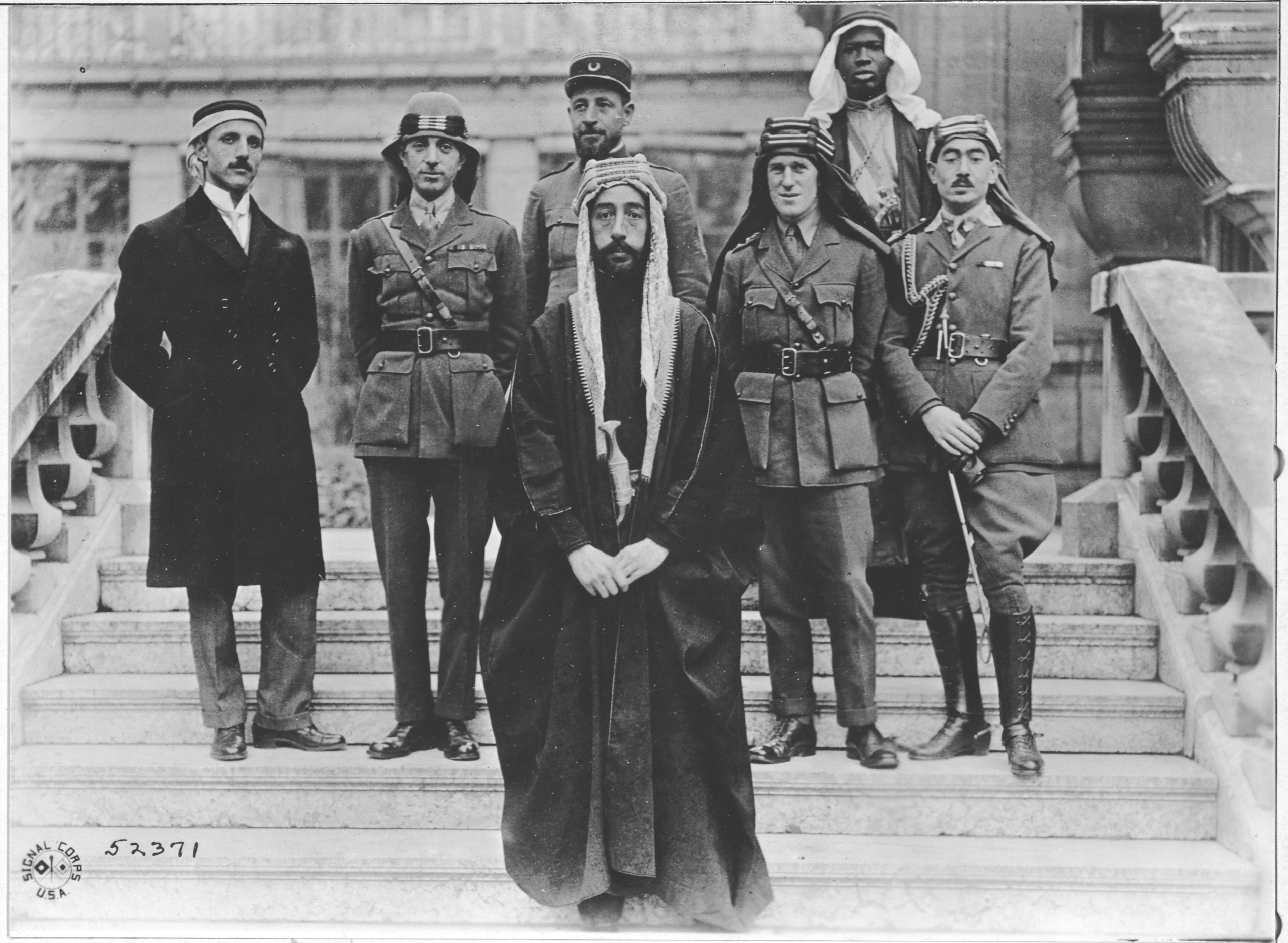

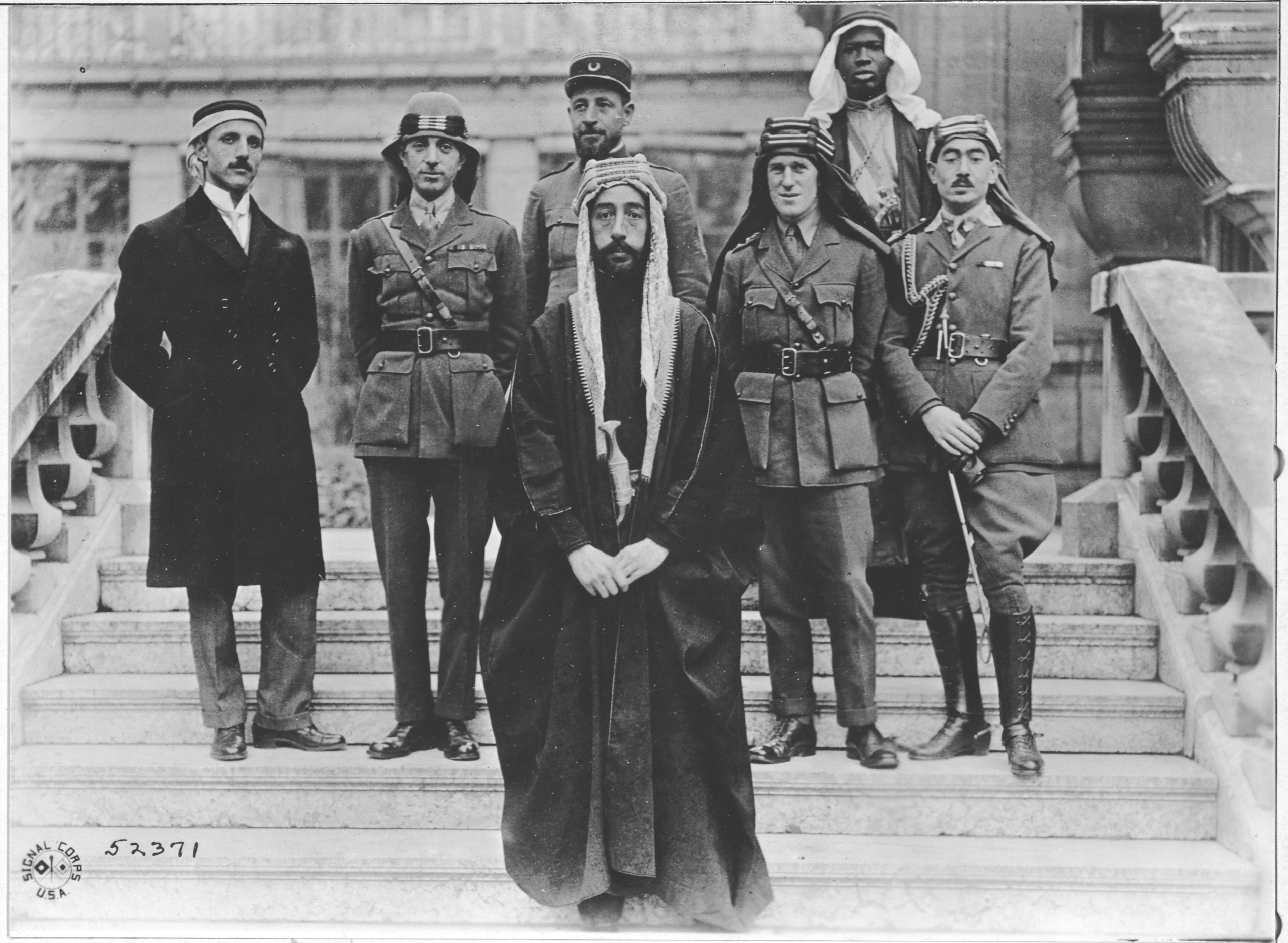

Faisal bin Hussein

Faisal I bin Al-Hussein bin Ali Al-Hashemi ( ar, ЩҒЩҠШөЩ„ Ш§Щ„ШЈЩҲЩ„ ШЁЩҶ Ш§Щ„ШӯШіЩҠЩҶ ШЁЩҶ Ш№Щ„ЩҠ Ш§Щ„ЩҮШ§ШҙЩ…ЩҠ, ''Faysal el-Evvel bin al-бёӨusayn bin AlД« el-HГўЕҹimГ®''; 20 May 1885 вҖ“ 8 September 1933) was King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria ...

вҖ”the third son of HusseinвҖ”was presented with the document that became known as the Damascus Protocol. Faisal was in Damascus to resume talks with the Arab secret societies al-Fatat

Al-Fatat or the Young Arab Society ( ar, Ш¬Щ…Ш№ЩҠШ© Ш§Щ„Ш№ШұШЁЩҠШ© Ш§Щ„ЩҒШӘШ§Ш©, JamвҖҷiyat al-вҖҷArabiya al-Fatat) was an underground Arab nationalist organization in the Ottoman Empire. Its aims were to gain independence and unify various Arab te ...

and Al-'Ahd that he had met in March/April; in the interim he had visited Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, Д°stanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, ОҡПүОҪПғП„ОұОҪП„О№ОҪОҝПҚПҖОҝО»О№ПӮ; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

to confront the Grand Vizier with evidence of an Ottoman plot to depose his father. The document declared the Arabs would revolt in alliance with the United Kingdom and in return the UK would recognize Arab independence in an area running from the 37th parallel near the Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains (Turkish language, Turkish: ''Toros DaДҹlarДұ'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain range, mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean Region, Turkey, Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolia# ...

on the southern border of Turkey, to be bounded in the east by Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

and the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, Ш®Щ„ЫҢШ¬ ЩҒШ§ШұШі, translit=xalij-e fГўrs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, Ш§ЩҺЩ„Щ’Ш®ЩҺЩ„ЩҗЩҠЩ’Ш¬ЩҸ ЩұЩ„Щ’Ш№ЩҺШұЩҺШЁЩҗЩҠЩҸЩ‘, Al-KhalД«j al-ЛҒArabД«), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bo ...

, in the west by the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

and in the south by the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea ( ar, Ш§ЩҺЩ„Щ’ШЁЩҺШӯШұЩ’ ЩұЩ„Щ’Ш№ЩҺШұЩҺШЁЩҗЩҠЩҸЩ‘, Al-Bahr al-ЛҒArabД«) is a region of the northern Indian Ocean bounded on the north by Pakistan, Iran and the Gulf of Oman, on the west by the Gulf of Aden, Guardafui Channel ...

.

Letters, July 1915 to March 1916

Following deliberations atTa'if

Taif ( ar, , translit=aб№ӯ-ṬДҒКҫif, lit=The circulated or encircled, ) is a city and governorate in the Makkan Region of Saudi Arabia. Located at an elevation of in the slopes of the Hijaz Mountains, which themselves are part of the Sarat M ...

between Hussein and his sons in June 1915, during which Faisal counselled caution, Ali

КҝAlД« ibn AbД« ṬДҒlib ( ar, Ш№ЩҺЩ„ЩҗЩҠЩ‘ ШЁЩ’ЩҶ ШЈЩҺШЁЩҗЩҠ Ш·ЩҺШ§Щ„ЩҗШЁ; 600 вҖ“ 661 CE) was the last of four Rightly Guided Caliphs to rule Islam (r. 656 вҖ“ 661) immediately after the death of Muhammad, and he was the first Shia Imam ...

argued against rebellion and Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, KargДұ, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

advocated action and encouraged his father to enter into correspondence with Sir Henry McMahon

Sir Arthur Henry McMahon (28 November 1862 вҖ“ 29 December 1949) was a British Indian Army officer and diplomat who served as the High Commissioner in Egypt from 1915 to 1917. He was also an administrator in British India and served twice a ...

; over the period 14 July 1915 to 10 March 1916. Ten lettersвҖ”five from each sideвҖ”were exchanged between Sir Henry McMahon and Sharif Hussein. McMahon was in contact with British Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

Edward Grey throughout; Grey was to authorise and be ultimately responsible for the correspondence.

Historians have used an excerpt from a private letter sent on 4 December 1915 by McMahon halfway through the eight-month period of the correspondence as evidence of possible British duplicity:

do not takethe idea of a future strong united independent Arab State ... too seriously ... the conditions of Arabia do not and will not for a very long time to come, lend themselves to such a thing ... I do not for one moment go to the length of imagining that the present negotiations will go far to shape the future form of Arabia or to either establish our rights or to bind our hands in that country. The situation and its elements are much too nebulous for that. What we have to arrive at now is to tempt the Arab people into the right path, detach them from the enemy and bring them on to our side. This on our part is at present largely a matter of words, and to succeed we must use persuasive terms and abstain from academic haggling over conditions вҖ“ whether about Baghdad or elsewhere.The ten letters are summarised in the table below, from the letters published in full in 1939 as '' Cmd. 5957'':

Legal status

Elie Kedourie

Elie Kedourie (25 January 1926, Baghdad вҖ“ 29 June 1992, Washington) was a British historian of the Middle East. He wrote from a liberal perspective, dissenting from many points of view taken as orthodox in the field. From 1953 to 1990, he ...

said the October letter was not a treaty and that even if it was considered to be a treaty, Hussein failed to fulfil his promises from his 18 February 1916 letter. Arguing to the contrary, Victor Kattan

The name Victor or Viktor may refer to:

* Victor (name), including a list of people with the given name, mononym, or surname

Arts and entertainment

Film

* ''Victor'' (1951 film), a French drama film

* ''Victor'' (1993 film), a French shor ...

describes the correspondence as a "secret treaty" and references that includes the correspondence. He also argues the UK government considered it to be a treaty during the 1919 Paris Peace Conference negotiations with the French over the disposal of Ottoman territory.

Arab Revolt, June 1916 to October 1918

McMahon's promises were seen by the Arabs as a formal agreement between themselves and the United Kingdom. British Prime MinisterDavid Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 вҖ“ 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

and Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary in the L ...

represented the agreement as a treaty during the post-war deliberations of the Council of Four. On this understanding the Arabs, under the command of Hussein's son Faisal, established a military force that fought, with inspiration from T. E. Lawrence ("Lawrence of Arabia"), against the Ottoman Empire during the Arab Revolt

The Arab Revolt ( ar, Ш§Щ„Ш«ЩҲШұШ© Ш§Щ„Ш№ШұШЁЩҠШ©, ) or the Great Arab Revolt ( ar, Ш§Щ„Ш«ЩҲШұШ© Ш§Щ„Ш№ШұШЁЩҠШ© Ш§Щ„ЩғШЁШұЩү, ) was a military uprising of Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I. On ...

. In an intelligence memo written in January 1916 Lawrence described Sherif Hussein's Arab Revolt as:

beneficial to us, because it marches with our immediate aims, the break up of the Islamic 'bloc' and the defeat and disruption of the Ottoman Empire, and because ''the states harif Husseinwould set up to succeed the Turks would be вҖҰ harmless to ourselves'' вҖҰ The Arabs are even less stable than the Turks. ''If properly handled they would remain in a state of political mosaic, a tissue of small jealous principalities incapable of cohesion'' (emphasis in original).In June 1916, the Arab Revolt began when an Arab army moved against Ottoman forces. They participated in the capture of

Aqaba

Aqaba (, also ; ar, Ш§Щ„Ш№ЩӮШЁШ©, al-КҝAqaba, al-КҝAgaba, ) is the only coastal city in Jordan and the largest and most populous city on the Gulf of Aqaba. Situated in southernmost Jordan, Aqaba is the administrative centre of the Aqaba Gove ...

h and the severing of the Hejaz railway, a strategic link through the Arab peninsula that ran from Damascus to Medina

Medina,, ', "the radiant city"; or , ', (), "the city" officially Al Madinah Al Munawwarah (, , Turkish: Medine-i MГјnevvere) and also commonly simplified as MadД«nah or Madinah (, ), is the second-holiest city in Islam, and the capital of the ...

. Meanwhile, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914вҖ“15), at the beginning ...

under the command of General Allenby

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby, (23 April 1861 вҖ“ 14 May 1936) was a senior British Army officer and Imperial Governor. He fought in the Second Boer War and also in the First World War, in which he led th ...

advanced into the Ottoman territories of Palestine and Syria. The British advance culminated in the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918 and the capitulation of the Ottoman Empire on 31 October 1918.

The Arab revolt is seen by historians as the first organized movement of Arab nationalism. It brought together Arab groups with the common goal to fight for independence from the Ottoman Empire for the first time. Much of the history of Arabian independence stemmed from the revolt beginning with the kingdom founded by Hussein. After the war was over, the Arab revolt had implications. Groups of people were classified according to whether they had fought in the revolt or and their ranks. In Iraq, a group of Sharifian officers from the Arab Revolt formed a political party of which they were head. The Hashemite

The Hashemites ( ar, Ш§Щ„ЩҮШ§ШҙЩ…ЩҠЩҲЩҶ, al-HДҒshimД«yЕ«n), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916вҖ“1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (192 ...

kingdom in Jordan is still influenced by the actions of Arab leaders in the revolt.

Related commitments, May 1916 to November 1918

SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement

The SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement between the UK and France was negotiated from the end of November 1915 until its agreement in principle on 3 January 1916. TheFrench government

The Government of France (French: ''Gouvernement français''), officially the Government of the French Republic (''Gouvernement de la République française'' ), exercises executive power in France. It is composed of the Prime Minister, wh ...

became aware of the UK's correspondence with Hussein during December 1915 but were not aware formal commitments had been made.

The agreement was exposed in December 1917; it was made public by the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Р‘РҫР»СҢСҲРөРІРёРәРёМҒ, from РұРҫР»СҢСҲРёРҪСҒСӮРІРҫМҒ ''bol'shinstvГі'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvГі'' (РұРҫР»СҢСҲРёРҪСҒСӮРІРҫМҒ), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, showing the countries were planning to split and occupy parts of the promised Arab country. Hussein was satisfied by two disingenuous telegrams from Sir Reginald Wingate

General Sir Francis Reginald Wingate, 1st Baronet, (25 June 1861 вҖ“ 29 January 1953) was a British general and administrator in Egypt and the Sudan. He earned the ''nom de guerre'' Wingate of the Sudan.

Early life

Wingate was born at Port Gla ...

, who had replaced McMahon as High Commissioner of Egypt, assuring him the British commitments to the Arabs were still valid and that the SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement was not a formal treaty.

After the Sykes-Picot Agreement was published by the Russian government, McMahon resigned.

Many sources contend the Sykes-Picot Agreement conflicted with the HusseinвҖ“McMahon Correspondence of 1915вҖ“1916. There were several points of difference, the most obvious being that Persia was placed in the British area and less obviously, the idea British and French advisors would be in control of the area designated as an Arab State. While the correspondence does not mention Palestine, Haifa and Acre were to be British and a reduced Palestine area was to be internationalized.

Balfour Declaration

In 1917, the UK issued the Balfour Declaration, promising to support the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. The declaration and the correspondence, as well as the Sykes-Picot agreement, are frequently considered together by historians because of the potential for incompatibility between them, particularly in regard to the disposition of Palestine. According toAlbert Hourani

Albert Habib Hourani ( ar, ШЈЩ„ШЁШұШӘ ШӯШЁЩҠШЁ ШӯЩҲШұШ§ЩҶЩҠ ''Albart бёӨabД«b бёӨЕ«rДҒnД«''; 31 March 1915 вҖ“ 17 January 1993) was a Lebanese British historian, specialising in the history of the Middle East and Middle Eastern studies.

Bac ...

, founder of the Middle East Centre at St Antony's College, Oxford

St Antony's College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1950 as the result of the gift of French merchant Sir Antonin Besse of Aden, St Antony's specialises in international relations, economics ...

; "The argument about the interpretation of these agreements is one which is impossible to end, because they were intended to bear more than one interpretation".

Hogarth message

Hussein asked for an explanation of the Balfour Declaration and in January 1918 Commander David Hogarth, head of theArab Bureau

The Arab Bureau was a section of the Cairo Intelligence Department established in 1916 during the First World War, and closed in 1920, whose purpose was the collection and dissemination of propaganda and intelligence about the Arab regions of ...

in Cairo, was dispatched to Jeddah to deliver a letter that was written by Sir Mark Sykes

Colonel Sir Tatton Benvenuto Mark Sykes, 6th Baronet (16 March 1879 вҖ“ 16 February 1919) was an English traveller, Conservative Party (UK), Conservative Party politician, and diplomatic advisor, particularly with regard to the Middle East at ...

on behalf of the UK government to Hussein, who was now King of Hejaz. The Hogarth message assured Hussein "the Arab race shall be given full opportunity of once again forming a nation in the world" and referred to " ... the freedom of the existing population both economic and political ...". According to Isaiah Friedman and Kedourie, Hussein accepted the Balfour Declaration while Charles D. Smith said both Friedman and Kedourie misrepresent documents and violate scholarly standards to reach their conclusions. Hogarth reported that Hussein "would not accept an independent Jewish State in Palestine, nor was I instructed to warn him that such a state was contemplated by Great Britain".

Declaration to the Seven

In light of the existing McMahonвҖ“Hussein correspondence and in the wake of the seemingly competing Balfour Declaration for the Zionists, as well as Russia's publication weeks later of the older and previously secret SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement with theRussia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eigh ...

and France, seven Syrian notables in Cairo from the newly formed Syrian Party of Unity

Syrians ( ar, ШіЩҸЩҲШұЩҗЩҠЩҸЩ‘ЩҲЩҶ, ''SЕ«riyyД«n'') are an Eastern Mediterranean ethnic group indigenous to the Levant. They share common Levantine Semitic roots. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend of both indi ...

(''Hizb al-Ittibad as-Suri'') issued a memorandum requesting clarification from the UK Government, including a "guarantee of the ultimate independence of Arabia". In response, issued on 16 June 1918, the Declaration to the Seven stated that British policy was that the future government of the regions of the Ottoman Empire that were occupied by Allied forces in World War I should be based on the consent of the governed

In political philosophy, the phrase consent of the governed refers to the idea that a government's legitimacy and moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society over which that politica ...

.

Allenby's assurance to Faisal

On 19 October 1918, General Allenby reported to the UK Government that he had given Faisal:official assurance that whatever measures might be taken during the period of military administration they were purely provisional and could not be allowed to prejudice the final settlement by the peace conference, at which no doubt the Arabs would have a representative. I added that the instructions to the military governors would preclude their mixing in political affairs, and that I should remove them if I found any of them contravening these orders. I reminded the Amir Faisal that the Allies were in honour bound to endeavour to reach a settlement in accordance with the wishes of the peoples concerned and urged him to place his trust whole-heartedly in their good faith.

Anglo-French Declaration of 1918

In the Anglo-French Declaration of 7 November 1918 the two governments stated that:The object aimed at by France and the United Kingdom in prosecuting in the East the War let loose by the ambition of Germany is the complete and definite emancipation of the peoples so long oppressed by the Turks and the establishment of national governments and administrations deriving their authority from the initiative and free choice of the indigenous populations.According to civil servant

Eyre Crowe

Sir Eyre Alexander Barby Wichart Crowe (30 July 1864 вҖ“ 28 April 1925) was a British diplomat, an expert on Germany in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. He is best known for his vehement warning, in 1907, that Germany's expansionism was mo ...

, who saw the original draft of the Declaration, "we had issued a definite statement against annexation in order (1) to quiet the Arabs and (2) to prevent the French annexing any part of Syria". The Declaration is considered by historians to have been misleading at best.

Post-War outcome, 1919 to 1925

Sherifian Plan

One day before the end of the war with the Ottomans, the British Foreign Office discussedT.E. Lawrence

Thomas Edward Lawrence (16 August 1888 вҖ“ 19 May 1935) was a British archaeologist, army officer, diplomat, and writer who became renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt (1916вҖ“1918) and the Sinai and Palestine Campaign (1915вҖ“191 ...

's "Sherifian Plan", in which Hussein's sons were proposed as puppet monarch

A puppet monarch is a majority figurehead who is installed or patronized by an imperial power to provide the appearance of local authority but to allow political and economic control to remain among the dominating nation.

A figurehead monarc ...

s in Syria and Mesopotamia. Part of the rationale was to satisfy a belief among the British public that a debt was owed to the Hashemites under the McMahon correspondence. Of Hussein's sons, Faisal was Lawrence's clear favourite, while Ali was not considered a strong leader, Zaid was considered to be too young and Abdullah was considered to be lazy.

Mandates

TheParis Peace Conference Agreements and declarations resulting from meetings in Paris include:

Listed by name

Paris Accords

may refer to:

* Paris Accords, the agreements reached at the end of the London and Paris Conferences in 1954 concerning the post-war status of Germ ...

between the allies to agree territorial divisions after the war was held in 1919. The correspondence was primarily relevant to the regions that were to become Palestine, Transjordan, Lebanon, Syria, Mesopotamia (Iraq) and the Arabian Peninsula. At the conference, Prince Faisal, speaking on behalf of King Hussein, did not ask for immediate Arab independence but recommended an Arab state under a British mandate.

On 6 January 1920, Prince Faisal initialed an agreement with French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 вҖ“ 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was ...

that acknowledged "the right of the Syrians to unite to govern themselves as an independent nation". A Pan-Syrian Congress, meeting in Damascus, declared an independent state of Syria on 8 March 1920. The new state included portions of Syria, Palestine and northern Mesopotamia, which under the SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement had been set aside for an independent Arab state or confederation of states. Faisal was declared the head of state as king. The April 1920 the San Remo conference

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Villa Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution pa ...

was hastily convened in response to Faisal's declaration. At the conference, the Allied Supreme Council

The Supreme War Council was a central command based in Versailles that coordinated the military strategy of the principal Allies of World War I: Britain, France, Italy, the US and Japan. It was founded in 1917 after the Russian revolution and wi ...

granted the mandates for Palestine and Mesopotamia to Britain, and those for Syria and Lebanon to France.

The United Kingdom and France agreed to recognize the provisional independence of Syria and Mesopotamia. Provisional recognition of Palestinian independence was not mentioned. France had decided to govern Syria directly and took action to enforce the French Mandate of Syria

The Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon (french: Mandat pour la Syrie et le Liban; ar, Ш§Щ„Ш§ЩҶШӘШҜШ§ШЁ Ш§Щ„ЩҒШұЩҶШіЩҠ Ш№Щ„Щү ШіЩҲШұЩҠШ§ ЩҲЩ„ШЁЩҶШ§ЩҶ, al-intidДҒb al-fransi 'ala suriya wa-lubnДҒn) (1923вҲ’1946) was a League of Nations mandate foun ...

before the terms had been accepted by the Council of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, SociГ©tГ© des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. The French intervened militarily at the Battle of Maysalun

The Battle of Maysalun ( ar, Щ…Ш№ШұЩғШ© Щ…ЩҠШіЩ„ЩҲЩҶ), also called the Battle of Maysalun Pass or the Battle of Khan Maysalun (french: Bataille de Khan Mayssaloun), was a four-hour battle fought between the forces of the Arab Kingdom of Syria a ...

in June 1920, deposing the indigenous Arab government and removing King Faisal from Damascus in August 1920. In Palestine, the United Kingdom appointed a High Commissioner and established their own mandatory regime. The January-1919 FaisalвҖ“Weizmann Agreement

The FaisalвҖ“Weizmann Agreement was a 3 January 1919 agreement between Emir Faisal, the third son of Hussein ibn Ali al-Hashimi, King of the short-lived Kingdom of Hejaz, and Chaim Weizmann, a Zionist leader who had negotiated the 1917 Balfour ...

was a short-lived agreement for ArabвҖ“Jewish cooperation on the development of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, which Faisal had mistakenly understood was to be within the Arab kingdom. Faisal did treat Palestine differently in his presentation to the Peace Conference on 6 February 1919, saying, "Palestine, in consequence of its universal character, be left on one side for the mutual consideration of all parties concerned".

The agreement was never implemented. At the same conference, US Secretary of State Robert Lansing

Robert Lansing (; October 17, 1864 вҖ“ October 30, 1928) was an American lawyer and diplomat who served as Counselor to the State Department at the outbreak of World War I, and then as United States Secretary of State under President Woodrow Wils ...

had asked Dr. Weizmann if the Jewish national home meant the establishment of an autonomous Jewish government. The head of the Zionist delegation had replied in the negative. Lansing was a member of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace

The American Commission to Negotiate Peace, successor to The Inquiry, participated in the peace negotiations at the Treaty of Versailles from January 18 to December 9, 1919. Frank Lyon Polk headed the commission in 1919. The peace conference was su ...

at Paris in 1919; he said the system of mandates was a device created by the Great Powers to conceal their division of the spoils of war under the colour of international law. If the territories had been ceded directly, the value of the former German and Ottoman territories would have been applied to offset the Allies' claims for war reparations. He also said Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as Prime Minister of South Africa, prime m ...

had been the author of the original concept.

Hussein's downfall

In 1919, King Hussein had refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. After February 1920, the British ceased to pay subsidy to him. In August 1920, five days after the signing of theTreaty of SГЁvres

The Treaty of SГЁvres (french: TraitГ© de SГЁvres) was a 1920 treaty signed between the Allies of World War I and the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ceded large parts of Ottoman territory to France, the United Kingdom, Greece and Italy, as well ...

, which formally recognized the Kingdom of Hejaz, Curzon asked Cairo to procure Hussein's signature to both treaties and agreed to make a payment of ВЈ30,000 conditional on signature. Hussein declined and in 1921, stated that he could not be expected to "affix his name to a document assigning Palestine to the Zionists and Syria to foreigners".

Following the 1921 Cairo Conference

The 1921 Cairo Conference, described in the official minutes as Middle East Conference held in Cairo and Jerusalem, March 12 to 30, 1921, was a series of meetings by British officials for examining and discussing Middle Eastern problems, and to fr ...

, Lawrence was sent to try and obtain the King's signature to a treaty in exchange for a proposed ВЈ100,000 annual subsidy; this attempt also failed. During 1923, the British again tried to settle outstanding issues with Hussein; this attempt also failed and Hussein continued refusing to recognize any of the mandates he perceived as being his domain. In March 1924, having briefly considered the possibility of removing the offending article from the treaty, the UK government suspended negotiations and within six months withdrew support in favour of its central Arabian ally Ibn Saud

Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud ( ar, Ш№ШЁШҜ Ш§Щ„Ш№ШІЩҠШІ ШЁЩҶ Ш№ШЁШҜ Ш§Щ„ШұШӯЩ…ЩҶ ШўЩ„ ШіШ№ЩҲШҜ, КҝAbd al КҝAzД«z bin КҝAbd ar RaбёҘman ДҖl SuКҝЕ«d; 15 January 1875Ibn Saud's birth year has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted ...

, who proceeded to conquer Hussein's kingdom.

Territorial reservations and Palestine

McMahon's letter to Hussein dated 24 October 1915 declared Britain's willingness to recognize the independence of the Arabs subject to certain exemptions. The original correspondence was conducted in both English and Arabic; slightly differing English translations are extant.

The correspondence was written first in English before being translated to Arabic and vice versa; the identity of the writer and translator is unclear. Kedourie and others assumed the likeliest candidate for primary author is

McMahon's letter to Hussein dated 24 October 1915 declared Britain's willingness to recognize the independence of the Arabs subject to certain exemptions. The original correspondence was conducted in both English and Arabic; slightly differing English translations are extant.

The correspondence was written first in English before being translated to Arabic and vice versa; the identity of the writer and translator is unclear. Kedourie and others assumed the likeliest candidate for primary author is Ronald Storrs

Sir Ronald Henry Amherst Storrs (19 November 1881 вҖ“ 1 November 1955) was an official in the British Foreign and Colonial Office. He served as Oriental Secretary in Cairo, Military Governor of Jerusalem, Governor of Cyprus, and Governor of No ...

. In his memoirs, Storrs said the correspondence was prepared by Husayn Ruhi

Hussein, Hussain, Hossein, Hossain, Huseyn, Husayn, Husein or Husain (; ar, ШӯЩҸШіЩҺЩҠЩ’ЩҶ ), coming from the triconsonantal root бёӨ-S-i-N ( ar, Шӯ Ші ЫҢ ЩҶ, link=no), is an Arabic name which is the diminutive of Hassan, meaning "good", "h ...

and then checked by Storrs. The Arab delegations to the 1939 Conference had objected to certain translations of text from Arabic to English and the Committee arranged for mutually agreeable translations that would render the English text "free from actual error".

"Portions of Syria" debate

The debate regarding Palestine arose because Palestine is not explicitly mentioned in the McMahonвҖ“Hussein Correspondence but is included within the boundaries that were initially proposed by Hussein. McMahon accepted the boundaries of Hussein "subject to modification" and suggested the modification that "portions of Syria lying to the west of the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo cannot be said to be purely Arab and should be excluded". Until 1920, British government documents suggested that Palestine was intended to be part of the Arab area; their interpretation changed in 1920 leading to public disagreement between the Arabs and the British, each side producing supporting arguments for their positions based on fine details of the wording and the historical circumstances of the correspondence.Jonathan Schneer

Jonathan Schneer (born August 9, 1948) is an American historian of modern Britain whose work ranges over labor, political, social, cultural, and diplomatic subjects. He is an emeritus professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

In addition ...

provides an analogy to explain the central dispute over the meaning:

Presume a line extending from the ''districts'' of New York, New Haven, New London, and Boston, excluding territory west from an imaginary coastal kingdom. If by ''districts'' one means "vicinity" or "environs," that is one thing with regard to the land excluded, but if one means "''vilayets''" or "provinces," or in the American instance "states," it is another altogether. There are no states of Boston, New London, or New Haven, just as there were no provinces of Hama and Homs, but there is a state of New York, just as there was a ''vilayet'' of Damascus, and territory to the west of New York State is different from territory to the west of the district of New York, presumably New York City and environs, just as territory to the west of the ''vilayet'' of Damascus is different from territory to the west of the district of Damascus, presumably the city of Damascus and its environs.More than 50 years after his initial report interpreting the correspondence for the British Foreign Office,

Arnold J. Toynbee

Arnold Joseph Toynbee (; 14 April 1889 вҖ“ 22 October 1975) was an English historian, a philosopher of history, an author of numerous books and a research professor of international history at the London School of Economics and King's Colle ...

published his perspectives on the continuing academic debate. Toynbee set out the logical consequences of interpreting McMahon's 'districts' or 'wilayahs' as provinces rather than vicinities:

(i) First alternative: McMahon was completely ignorant of Ottoman administrative geography. He did not know that the Ottoman vilayet of Aleppo extended westward to the coast, and he did not know that there were no Ottoman vilayets of Homs and Hama. It seems to me incredible that McMahon can have been as ill-informed as this, and that he would not have taken care to inform himself correctly when he was writing a letter in which he was making very serious commitments on HMG's account.

(ii) Second alternative: McMahon was properly acquainted with Ottoman administrative geography, and was using the word 'wilayahs' equivocally. Apropos of Damascus, he was using it to mean 'Ottoman provinces'; apropos of Homs and Hama, and Aleppo, he was using it to mean 'environs'. This equivocation would have been disingenuous, impolitic, and pointless. I could not, and still cannot, believe that McMahon behaved so irresponsibly.

"Without detriment to France" debate

In the letter of 24 October, the English version reads: " ... we accept those limits and boundaries; and in regard to those portions of the territories therein in which Great Britain is free to act without detriment to the interests of her ally France" At a meeting in Whitehall in December 1920 the English and Arabic texts of McMahon's correspondence with Sharif Husein were compared. As one official, who was present, said:In the Arabic version sent to King Husain this is so translated as to make it appear that Gt Britain is free to act without detriment to France in the whole of the limits mentioned. This passage of course had been our sheet anchor: it enabled us to tell the French that we had reserved their rights, and the Arabs that there were regions in which they wd have eventually to come to terms with the French. It is extremely awkward to have this piece of solid ground cut from under our feet. I think that HMG will probably jump at the opportunity of making a sort of amende by sending Feisal to Mesopotamia.James Barr wrote that although McMahon had intended to reserve the French interests, he became a victim of his own cleverness because the translator Ruhi lost the qualifying sense of the sentence in the Arabic version. In a Cabinet analysis of diplomatic developments prepared in May 1917

The Hon.

''The Honourable'' ( British English) or ''The Honorable'' (American English; see spelling differences) (abbreviation: ''Hon.'', ''Hon'ble'', or variations) is an honorific style that is used as a prefix before the names or titles of certa ...

William Ormsby-Gore, MP, wrote:

Declassified British Cabinet papers include a telegram dated 18 October 1915 from Sir Henry McMahon to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Grey requesting instructions. UK National ArchivesCAB/24/214, CP 271 (30)

. McMahon described conversations with a

Muhammed Sharif al-Faruqi Lieutenant Muhammed Sharif al-Faruqi (1891 - 1920; Arabic: Щ…ШӯЩ…ШҜ ШҙШұЩҠЩҒ Ш§Щ„ЩҒШ§ШұЩҲЩӮЩҠ) was an Arab Ottoman staff officer from Mosul. He was stationed in Damascus and played a pivotal role in the events leading up to the Arab Revolt.

He wa ...

, a member of the Abd party who said the British could satisfy the demands of the Syrian Nationalists for the independence of Arabia. Faroqi had said the Arabs would fight if the French attempted to occupy the cities of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo, but he thought they would accept some modification of the north-western boundaries proposed by the Sherif of Mecca. Based on these conversations, McMahon suggested the language; "In so far as Britain was free to act without detriment to the interests of her present Allies, Great Britain accepts the principle of the independence of Arabia within limits propounded by the Sherif of Mecca". Lord Grey authorized McMahon to pledge the areas requested by the Sharif subject to the reserve for the Allies.

Arab position

The Arab position was that they could not refer to Palestine because that lay well to the south of the named places. In particular, the Arabs argued the ''vilayet'' (province) of Damascus did not exist and that the district (''sanjak'') of Damascus only covered the area surrounding the city and that Palestine was part of the ''vilayet'' of Syria A-Sham, which was not mentioned in the exchange of letters. Supporters of this interpretation also note that during the war, thousands of proclamations were dropped in all parts of Palestine carrying a message from the Sharif Hussein on one side and a message from the British Command on the other, saying "that an Anglo-Arab agreement had been arrived at securing the independence of the Arabs".British position

The undated memorandum GT 6185 (from CAB 24/68/86) of November 1918 was prepared by the British historianArnold Toynbee Arnold Toynbee may refer to:

* Arnold Toynbee (historian, born 1852) (d. 1883), British economic historian

* Arnold J. Toynbee (1889вҖ“1975), British historian and author of ''A Study of History''

{{hndis ...

in 1918 while working in the Political Intelligence Department Political Intelligence Department may refer to:

* Political Intelligence Department (1918вҖ“1920)

* Political Intelligence Department (1939вҖ“1943)

{{Disambig ...

. Crowe, the Permanent Under-Secretary, ordered them to be placed in the Foreign Office dossier for the Peace Conference. After arriving in Paris, General Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

required that the memoranda be summarized and Toynbee produced the document GT 6506 (maps illustrating it are GT6506A

). The two last were circulated as E.C.2201 and considered at a meeting of the Eastern Committee

The Eastern Committee (EC) was an interdepartmental committee of the War Cabinet of the British Government, created towards the end of World War I. Its function was to formulate a coherent Middle East policy, resolving conflicting visions of invo ...

(No.41) of the Cabinet on 5 December 1918, which was chaired by Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 вҖ“ 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

, Jan Smuts, Lord Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary in the L ...

, Lord Robert Cecil

Edgar Algernon Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood, (14 September 1864 вҖ“ 24 November 1958), known as Lord Robert Cecil from 1868 to 1923,As the younger son of a Marquess, Cecil held the courtesy title of "Lord". However, he ...

, General Sir Henry Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff; representatives of the Foreign Office, the India Office, the Admiralty, the War Office, and the Treasury were present. T. E. Lawrence also attended.

The Eastern Committee met nine times in November and December to draft a set of resolutions on British policy for the benefit of the negotiators.On 21 October, the War Cabinet asked Smuts to prepare the summarized peace brief and Smuts asked Erle Richards to carry out this task. Richards distilled Toynbee's GT6506 and the resolutions of the Eastern Committee into a "P-memo" (P-49) for use by the Peace Conference delegates.

In the public arena, Balfour was criticized in the House of Commons when the Liberals and Labour Socialists moved a resolution "That secret treaties with the allied governments should be revised, since, in their present form, they are inconsistent with the object for which this country entered the war and are, therefore, a barrier to a democratic peace". In response to growing criticism arising from the seemingly contradictory commitments undertaken by the United Kingdom in the McMahon-Hussein correspondence, the SykesвҖ“Picot Agreement and the Balfour declaration, the 1922 Churchill White Paper

The Churchill White Paper of 3 June 1922 (sometimes referred to as "British Policy in Palestine") was drafted at the request of Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, partly in response to the 1921 Jaffa Riots. The offic ...

took the position Palestine had always been excluded from the Arab area. Although this directly contradicted numerous previous government documents, those documents were not known to the public. As part of preparations for this White Paper, Sir John Shuckberg of the British Colonial Office had exchanged correspondence with McMahon; reliance was placed on a 1920 memorandum by Major Hubert Young, who had noted that in the original Arabic text, the word translated as "districts" in English was "vilayets", the largest class of administrative district into which the Ottoman Empire was divided. He concluded "district of Damascus", i.e., "vilayet of Damascus", must have referred to the vilayet of which Damascus was the capital, the Vilayet of Syria. This vilayet extended southwards to the Gulf of Aqaba

The Gulf of Aqaba ( ar, Ш®ЩҺЩ„ЩҗЩҠШ¬ЩҸ ЩұЩ„Щ’Ш№ЩҺЩӮЩҺШЁЩҺШ©Щҗ, KhalД«j al-КҝAqabah) or Gulf of Eilat ( he, ЧһЧӨЧЁЧҘ ЧҗЧҷЧңЧӘ, MifrГЎtz EilГЎt) is a large gulf at the northern tip of the Red Sea, east of the Sinai Peninsula and west of the Arabi ...

but excluded most of Palestine.

While some British governments occasionally stated that the intent of the McMahon Correspondence was not to promise Palestine to Hussein, they have occasionally acknowledged the flaws in the legal terminology of the McMahonвҖ“Hussein Correspondence that make this position problematic. The weak points of the government's interpretation were acknowledged in a detailed memorandum by the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in 1939.

Michael McDonnell

Sir Michael Francis Joseph McDonnell (1882вҖ“1956) was Chief Justice of Palestine between 1927 and 1936. He had previously been a colonial civil servant and Acting Chief Justice of Sierra Leone.

Education and career

Born in London to an I ...

to the committee that said whatever meaning McMahon had intended was of no legal consequence because it was his actual statements that constituted the pledge from His Majesty's Government. The Arab representatives also said McMahon had been acting as an intermediary for the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Grey. Speaking in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster ...

on 27 March 1923, Lord Grey said he had serious doubts about the validity of the Churchill White Paper's interpretation of the pledges he, as Foreign Secretary, had caused to be given to the Sharif Hussein in 1915. The Arab representatives suggested a search for evidence in the files of the Foreign Office might clarify the Secretary of State's intentions.

See also

*Pan-Arabism

Pan-Arabism ( ar, Ш§Щ„ЩҲШӯШҜШ© Ш§Щ„Ш№ШұШЁЩҠШ© or ) is an ideology that espouses the unification of the countries of North Africa and Western Asia from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Sea, which is referred to as the Arab world. It is closely c ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

Specialised works

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *General histories

* * * *Works by involved parties

* *pdf version

(0.3 MB)

Original pdf

(7.3MB) * * * * * * * *

External links

The Arabian Peninsula in 1914

Җ”UK National Archives (including information on the HusseinвҖ“McMahon Correspondence) {{DEFAULTSORT:Mcmahon-Hussein Correspondence 1915 documents 1915 in international relations 1915 in Ottoman Syria 1916 documents 1916 in international relations 1916 in Ottoman Syria Arab Revolt Collection of The National Archives (United Kingdom) Correspondences Documents of Mandatory Palestine France in World War I United Kingdom in World War I World War I documents