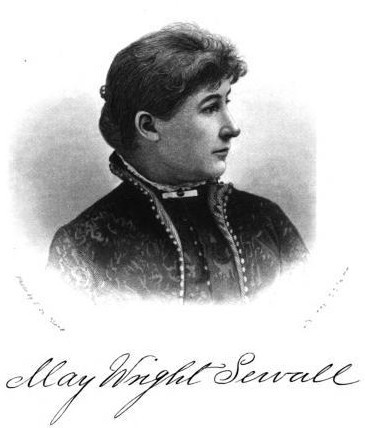

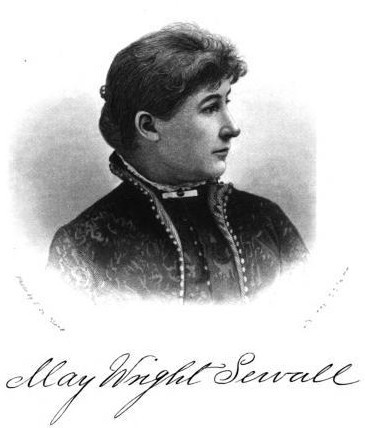

May Wright Sewall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

May Wright Sewall (May 27, 1844 – July 22, 1920) was an American reformer, who was known for her service to the causes of education, women's rights, and world peace. She was born in Greenfield,

May spent more than three decades as an Indianapolis educator, twenty-five of them at the Girls' Classical School, which she founded with her second husband, Theodore. The school opened with forty-four students in September 1881. May served as the school's principal and taught literature. The Girls' Classical School became "one of the three leading girls' schools in Indianapolis.""Biographical Sketch" in

The girls' school initially occupied a building on the southeast corner of Pennsylvania and St. Joseph streets. In 1884 it expanded to new facilities in a three-story brick building at 426 North Pennsylvania Street. In 1886, a year after Theodore's death, Sewall leased a double brick building at 343 and 345 North Pennsylvania to serve as a school residence for students who lived outside the city.

The school's curriculum did not offer the traditional courses for girls at the time, such as art or music. Instead, its college preparatory courses included classical studies, modern languages, and science. The school's academic courses were based on Harvard's entrance requirements for women, which included admission requirements for

May spent more than three decades as an Indianapolis educator, twenty-five of them at the Girls' Classical School, which she founded with her second husband, Theodore. The school opened with forty-four students in September 1881. May served as the school's principal and taught literature. The Girls' Classical School became "one of the three leading girls' schools in Indianapolis.""Biographical Sketch" in

The girls' school initially occupied a building on the southeast corner of Pennsylvania and St. Joseph streets. In 1884 it expanded to new facilities in a three-story brick building at 426 North Pennsylvania Street. In 1886, a year after Theodore's death, Sewall leased a double brick building at 343 and 345 North Pennsylvania to serve as a school residence for students who lived outside the city.

The school's curriculum did not offer the traditional courses for girls at the time, such as art or music. Instead, its college preparatory courses included classical studies, modern languages, and science. The school's academic courses were based on Harvard's entrance requirements for women, which included admission requirements for

Sewall is best known for her work in the woman's suffrage movement, especially her ability to organize and unify women's groups through a concept she called the council idea. The national and international councils she helped organize brought women of diverse backgrounds together to work toward larger interests. Beginning in 1878, when she helped form the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society, Sewall became active in campaigns for female suffrage in Indiana and was heavily involved in woman's suffrage at the national level.

Sewall is best known for her work in the woman's suffrage movement, especially her ability to organize and unify women's groups through a concept she called the council idea. The national and international councils she helped organize brought women of diverse backgrounds together to work toward larger interests. Beginning in 1878, when she helped form the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society, Sewall became active in campaigns for female suffrage in Indiana and was heavily involved in woman's suffrage at the national level.

May Wright Sewall Papers

Indianapolis Marion County Public Library

May Wright Sewall Papers crowdsourcing transcription project

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sewall, Mary Wright 1844 births 1920 deaths People from Indianapolis People from Greenfield, Wisconsin American feminists American suffragists People from Plainwell, Michigan American Unitarians Indianapolis Museum of Art people

Milwaukee County, Wisconsin

Milwaukee County is located in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. At the 2020 census, the population was 939,489, down from 947,735 in 2010. It is both the most populous and most densely populated county in Wisconsin, and the 45th most populous coun ...

. Sewall served as chairman of the National Woman Suffrage Association

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement spl ...

's executive committee from 1882 to 1890, and was the organization's first recording secretary. She also served as president of the National Council of Women of the United States

The National Council of Women of the United States (NCW/US) is the oldest nonsectarian organization of women in America. Officially founded in 1888, the NCW/US is an accredited non-governmental organization (NGO) with the Department of Public In ...

from 1897 to 1899, and president of the International Council of Women

The International Council of Women (ICW) is a women's rights organization working across national boundaries for the common cause of advocating human rights for women. In March and April 1888, women leaders came together in Washington, D.C., with ...

from 1899 to 1904. In addition, she helped organize the General Federation of Women's Clubs

The General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC), founded in 1890 during the Progressive Movement, is a federation of over 3,000 women's clubs in the United States which promote civic improvements through volunteer service. Many of its activities ...

, and served as its first vice-president. Sewall was also an organizer of the World's Congress of Representative Women

The World's Congress of Representative Women was a week-long convention for the voicing of women's concerns, held within The Woman's Building (Chicago), The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition (Chicago, May 1893). At 81 meetings, ...

, which was held in conjunction with the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordi ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

in 1893. U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

appointed her as a U.S. representative of women to the Exposition Universelle (1900)

The Exposition Universelle of 1900, better known in English as the 1900 Paris Exposition, was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 14 April to 12 November 1900, to celebrate the achievements of the past century and to accelerate developmen ...

in Paris.

Sewall became chairman of the National Council of Women's standing committee on peace and arbitration in 1904 and chaired and organized the International Conference of Women Workers to Promote Permanent Peace at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

in 1915. Sewall was also among the sixty delegates who joined Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

's Peace Ship

The Peace Ship was the common name for the ocean liner ''Oscar II'', on which American industrialist Henry Ford organized and launched his 1915 amateur peace mission to Europe; Ford chartered the ''Oscar II'' and invited prominent peace activists t ...

, an unofficial peace expedition aboard the ''Oscar II'' in an unsuccessful attempt to halt the war in Europe in 1915.

In addition to her work on women's rights Sewall was as an educator and lecturer, civic organizer, and spiritualist. In 1882 she and her second husband, Theodore Lovett Sewall, founded the Girls' Classical School in Indianapolis. The school was known for its rigorous college preparatory courses, physical education for women, and innovative adult education and domestic science programs. Sewall also helped to establish several civic organizations, most notably the Indianapolis Woman's Club, the Indianapolis Propylaeum, the Art Association of Indianapolis (later known as the Indianapolis Museum of Art

The Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA) is an encyclopedic art museum located at Newfields, a campus that also houses Lilly House, The Virginia B. Fairbanks Art & Nature Park: 100 Acres, the Gardens at Newfields, the Beer Garden, and more. It i ...

), the Contemporary Club of Indianapolis, and the John Herron Art Institute, which became the Herron School of Art and Design

Herron School of Art and Design, officially IU Herron School of Art and Design, is a public art school at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) in Indianapolis, Indiana. It is a professional art school and has been accredited ...

at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th st ...

(IUPUI). Although Sewall converted to spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (when not lowercase) ...

in 1897, she concealed her spiritualist activities from the public until the publication of her book, ''Neither Dead Nor Sleeping'', two months prior to her death in 1920.

Early life and education

Mary Eliza Wright was born on May 27, 1844, in Greenfield,Milwaukee County, Wisconsin

Milwaukee County is located in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. At the 2020 census, the population was 939,489, down from 947,735 in 2010. It is both the most populous and most densely populated county in Wisconsin, and the 45th most populous coun ...

. She was the second daughter and the youngest of four children born to Philander Montague Wright and his wife, Mary Weeks (Bracket) Wright. Mary Eliza's parents migrated from New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

to Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, where they met and married, then moved to Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, where Philander, a former teacher, became a farmer. As a child Mary Eliza called herself May, a name she would retain throughout her life.

Philander Wright taught May at home, but she also attended public school in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin

Wauwatosa (; known informally as Tosa; originally Wau-wau-too-sa or Hart's Mill) is a city in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 48,387 at the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census. Wauwatos ...

, and Bloomington, Wisconsin

Bloomington is a village in Grant County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 735 as of the 2010 census. The village is located within the Town of Bloomington.

Geography

Bloomington is located at .

According to the United States Census ...

. He believed in equal opportunities among men and women, and encouraged his daughter to pursue higher education.

After teaching in Waukesha County, Wisconsin

Waukesha County () is a county in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 United States Census, the population was 406,978, making it the third-most populous county in Wisconsin. Its county seat and largest city is Waukesha.

Waukesha Co ...

, from 1863 to 1865, May left the state to pursue studies at Northwestern Female College in Evanston, Illinois

Evanston ( ) is a city, suburb of Chicago. Located in Cook County, Illinois, United States, it is situated on the North Shore along Lake Michigan. Evanston is north of Downtown Chicago, bordered by Chicago to the south, Skokie to the west, Wil ...

. The college was a respected school for women's education that was later absorbed into Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

. May was awarded a laureate of science in 1866 and a Master of Arts degree in 1871.

Marriage and family

May's first husband, Edwin W. Thompson, was an educator, as was her second husband, Theodore Lovett Sewall. She had no children from either marriage.Boomhower, p. 16.Robinson, p. 39. May and Edwin W. Thompson, a mathematics teacher fromPaw Paw, Michigan

Paw Paw is a village in the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 3,534 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Van Buren County.

Overview

The village is located at the confluence of the east and south branches of the Paw Paw River ...

, were married on March 2, 1872. The couple met while she was teaching in Plainwell, Michigan

Plainwell is a city in Allegan County in the U.S. state of Michigan. The population was 3,804 at the 2010 census.

Plainwell is located on M-89 just east of its junction with US 131. The city of Otsego is about to the west. The city of ...

. In 1873 the Thompsons moved to Franklin, Indiana

Franklin is a city in Johnson County, Indiana, United States. The population was 23,712 at the 2010 census. Located about south of Indianapolis, the city is the county seat of Johnson County. The site of Franklin College, the city attracts n ...

, where they continued their careers as educators and school administrators, but they resigned the following year to assume teaching positions at Indianapolis High School, later known as Shortridge High School

Shortridge High School is a public high school located in Indianapolis, Indiana, United States. Shortridge is the home of the International Baccalaureate and arts and humanities programs of the Indianapolis Public Schools district.(IPS). Originall ...

. The Thompsons moved to Indianapolis

Indianapolis (), colloquially known as Indy, is the state capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the seat of Marion County. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the consolidated population of Indianapolis and Marion ...

in 1874 and lived in a neighborhood known as College Corner. They became members of the College Corner Club, joined the Indianapolis Woman Suffrage Society, which was formed in April 1873, and were members of a local Unitarian church. After contracting tuberculosis, Thompson went to a sanitarium in Asheville, North Carolina

Asheville ( ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Buncombe County, North Carolina. Located at the confluence of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers, it is the largest city in Western North Carolina, and the state's 11th-most populous cit ...

, to try to regain his health. May joined him at Asheville, where he died on August 19, 1875. May returned to Indianapolis after his death to resume teaching.

May married Theodore Lovett Sewall on October 31, 1880. The two met at a Unitarian church service in Indianapolis. Sewall was born in Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

and raised in Wilmington, Delaware

Wilmington ( Lenape: ''Paxahakink /'' ''Pakehakink)'' is the largest city in the U.S. state of Delaware. The city was built on the site of Fort Christina, the first Swedish settlement in North America. It lies at the confluence of the Christina ...

. He graduated from Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

in 1874, and opened the Indianapolis Classical School for boys on September 25, 1876. Their marriage was an equal partnership. Sewall's steady disposition balanced his "energetic" and "sometimes impractical wife. "Stephens, p. 278.

May and Theodore Sewall were liberal-minded progressives, whose home became a social center in the city. The couple hosted weekly gatherings of Indianapolis's intellectual community at their home to discuss the major topics of the day. They also welcomed numerous overnight guests, many of whom were well-known authors, artists, politicians, suffragists, and other social activists. Theodore, a supporter of women's rights, encouraged his wife's interests in social reform, specifically educational advancement for women and women's suffrage. He died from tuberculosis at their Indianapolis home on December 23, 1895.

Early career

May began her teaching career in 1863, when she took a job at Waukesha County, Wisconsin, but left in 1865 to attend college in Evanston, Illinois. She returned to teaching after earning a college diploma in 1866, and took a job atGrant County, Wisconsin

Grant County is a county located in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census, the population was 51,938. Its county seat is Lancaster. The county is named after the Grant River, in turn named after a fur trader who lived in the area ...

. She later moved to Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

. In 1869 May became a high school teacher at Plainwell, Michigan, and subsequently its first woman principal.

In 1871 May moved to Franklin, Indiana, where she taught German at the local high school. She returned to Michigan in 1872 to marry to Edwin Thompson. The newlyweds moved to Franklin the following year. May became principal at Franklin's high school; Edwin was superintendent of schools. In 1874 the Thompsons resigned their positions at Franklin and moved to Indianapolis, where they became teachers at Indianapolis High School. May taught German and English literature; Edwin taught business classes.Boomhower, p. 17.

After her marriage to Sewall in 1880, May resigned her position at Indianapolis High School. May taught German and literature at the Indianapolis Classical School for boys; Theodore was the school's principal.

Educator

May spent more than three decades as an Indianapolis educator, twenty-five of them at the Girls' Classical School, which she founded with her second husband, Theodore. The school opened with forty-four students in September 1881. May served as the school's principal and taught literature. The Girls' Classical School became "one of the three leading girls' schools in Indianapolis.""Biographical Sketch" in

The girls' school initially occupied a building on the southeast corner of Pennsylvania and St. Joseph streets. In 1884 it expanded to new facilities in a three-story brick building at 426 North Pennsylvania Street. In 1886, a year after Theodore's death, Sewall leased a double brick building at 343 and 345 North Pennsylvania to serve as a school residence for students who lived outside the city.

The school's curriculum did not offer the traditional courses for girls at the time, such as art or music. Instead, its college preparatory courses included classical studies, modern languages, and science. The school's academic courses were based on Harvard's entrance requirements for women, which included admission requirements for

May spent more than three decades as an Indianapolis educator, twenty-five of them at the Girls' Classical School, which she founded with her second husband, Theodore. The school opened with forty-four students in September 1881. May served as the school's principal and taught literature. The Girls' Classical School became "one of the three leading girls' schools in Indianapolis.""Biographical Sketch" in

The girls' school initially occupied a building on the southeast corner of Pennsylvania and St. Joseph streets. In 1884 it expanded to new facilities in a three-story brick building at 426 North Pennsylvania Street. In 1886, a year after Theodore's death, Sewall leased a double brick building at 343 and 345 North Pennsylvania to serve as a school residence for students who lived outside the city.

The school's curriculum did not offer the traditional courses for girls at the time, such as art or music. Instead, its college preparatory courses included classical studies, modern languages, and science. The school's academic courses were based on Harvard's entrance requirements for women, which included admission requirements for Smith

Smith may refer to:

People

* Metalsmith, or simply smith, a craftsman fashioning tools or works of art out of various metals

* Smith (given name)

* Smith (surname), a family name originating in England, Scotland and Ireland

** List of people wi ...

, Vassar, and Wellesley, among other colleges. The girls' school also offered a course of study for women who did not plan to enroll in college.Stephens, p. 279.

In addition to academic classes, Sewall introduced dress reform and physical education for young women, which was not typical for a time when corsets, bustles, and petticoats were the norm. Sewall required students to wear shoes with low and broad heels. She also urged, but did not require, parents to provide students with simple dress that consisted of a "kilt skirt and loose waist with a sash" to allow for more freedom of movement.

After 1885, when Sewall became the sole principal of the school, she added innovative programs such as adult education and courses in domestic science (later known as home economics), which included classes in physics, chemistry, and cooking. These courses were among the first of their kind to be offered in Indiana or the nation.

By 1900 the Girls' Classical School was having financial problems as rival private schools were established in the city and public high schools became more common in Indiana.Stephens, p. 281. Sewall's more progressive ideas may also have led to the drop in enrollment.

The Sewalls operated the school together until Theodore's death in 1885. May continued to run the school until her retirement in 1907. In 1905 she partnered with Anna F. Weaver, a former student and a graduate of Stanford University, to jointly operate the school. In 1907 Sewall announced her retirement, ending her twenty-five year career at the school. Sewall sold the school's main building for $20,500. Weaver continued to run the Girls' Classical School from the double brick building they used as a school residence. Weaver permanently closed the school in 1910.

Sewall had no immediate plans after her retirement. In 1907 she donated items from her Indianapolis home to local organizations and left the city to deliver a public lecture at Eliot, Maine

Eliot is a town in York County, Maine, United States. Originally settled in 1623, it was formerly a part of Kittery, Maine, to its east. After Kittery, it is the next most southern town in the state of Maine, lying on the Piscataqua River across f ...

, and continued her work in the women's movement.

Civic organizer

While a resident of Indianapolis Sewall was known for her active involvement in numerous civic and cultural organizations. Sewall's most significant civic work included founding the Indianapolis Woman's Club, the Indianapolis Propylaeum, the Art Association of Indianapolis, later known as theIndianapolis Museum of Art

The Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA) is an encyclopedic art museum located at Newfields, a campus that also houses Lilly House, The Virginia B. Fairbanks Art & Nature Park: 100 Acres, the Gardens at Newfields, the Beer Garden, and more. It i ...

, and its affiliated art school, the John Herron Art Institute, which later became the Herron School of Art and Design

Herron School of Art and Design, officially IU Herron School of Art and Design, is a public art school at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) in Indianapolis, Indiana. It is a professional art school and has been accredited ...

at Indiana University – Purdue University Indianapolis

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th st ...

(IUPUI). Many praised her work, but others criticized her as being "too dominant." Sewall thought that people "misunderstood her."

Indianapolis Woman’s Club

Sewall was among the small group of women who founded the Indianapolis Woman's Club, whose first meeting was held on February 18, 1875. The club was organized to further the "mental and social culture" of its members.Boomhower, p. 19. Although it was not the first, the Indianapolis Woman's Club is the longest running of its kind in the state.Boomhower, p. 18. Eliza Hendricks, wife ofIndiana governor

The governor of Indiana is the head of government of the State of Indiana. The governor is elected to a four-year term and is responsible for overseeing the day-to-day management of the functions of many agencies of the Indiana state government ...

Thomas A. Hendricks

Thomas Andrews Hendricks (September 7, 1819November 25, 1885) was an American politician and lawyer from Indiana who served as the 16th governor of Indiana from 1873 to 1877 and the 21st vice president of the United States from March until his ...

, was the club's first president. Sewall became chair of its executive committee.James, James, and Boyer, p. 270. Formed at a time when most Indianapolis residents opposed a woman's role outside the home, the club encouraged "a liberal interchange of thoughts. ""Historical Sketch" in The club's activities also helped train future leaders in civic affairs and in the national effort to secure voting rights for women.

Indianapolis Propylaeum

In 1888 Sewall encouraged the Indianapolis Woman's Club to consider erecting a building to serve as a meeting place for the club as well as other literary, artistic, and social organizations in the city. The effort led to establishing the Indianapolis Propylaeum, named after the Greek word ''propylaion'', meaning gateway to higher culture. The Propylaeum incorporated on June 6, 1888, as a stock company of Indianapolis women. Its initial $15,000 in stock, offered exclusively to women at $25 per share, helped fund construction of their first building at 17 East North Street, between Meridian and Pennsylvania streets. Sewall was elected president of the corporation, a position she retained until 1907, when she resigned and left Indianapolis. In June 1923, three years after Sewall's death, the City of Indianapolis acquired the Propylaeum's first building as a site for a new war memorial, and the organization erected a new building at 14th and Delaware streets."Historical Sketch" inArt Association of Indianapolis

In 1883 Sewall convened the initial meeting to organize the Art Association of Indianapolis, forerunner to the Indianapolis Museum of Art. She was a charter member of the group, which formally incorporated in October 1883. Sewall also helped found its affiliated art school, which became known as the John Herron Art Institute. Sewall served as the art association's first recording secretary, and as its president from 1893 to 1898. The Art Association acquired the Tinker House property at 16th and Pennsylvania streets, where their art school opened in March 1902. Sewall also attended the groundbreaking for the Art Association's new museum and art school, whose cornerstone was laid on November 25, 1905.Other civic affiliations

May and Theodore Sewall organized and were charter members of Indianapolis's Contemporary Club, which was established in their home in 1890. Club membership was open to men and women on equal terms. May served as the club's first president. Sewall was also founder and president from 1886 to 1887 and again from 1888 to 1889 of the Western Association of Collegiate Alumnae which later merged with theAssociation of Collegiate Alumnae

The American Association of University Women (AAUW), officially founded in 1881, is a non-profit organization that advances equity for women and girls through advocacy, education, and research. The organization has a nationwide network of 170,000 ...

, the forerunner to the American Association of University Women

The American Association of University Women (AAUW), officially founded in 1881, is a non-profit organization that advances equity for women and girls through advocacy, education, and research. The organization has a nationwide network of 170,000 ...

.

Suffragist

Sewall is best known for her work in the woman's suffrage movement, especially her ability to organize and unify women's groups through a concept she called the council idea. The national and international councils she helped organize brought women of diverse backgrounds together to work toward larger interests. Beginning in 1878, when she helped form the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society, Sewall became active in campaigns for female suffrage in Indiana and was heavily involved in woman's suffrage at the national level.

Sewall is best known for her work in the woman's suffrage movement, especially her ability to organize and unify women's groups through a concept she called the council idea. The national and international councils she helped organize brought women of diverse backgrounds together to work toward larger interests. Beginning in 1878, when she helped form the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society, Sewall became active in campaigns for female suffrage in Indiana and was heavily involved in woman's suffrage at the national level.

Indiana activist

Sewall joined the woman suffrage movement in March 1878, when she was among the nine women and one man who secretly met to discuss formation of the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society. Sewall's work with this group brought her national recognition in women's movement, most notably her affiliation with theNational Woman Suffrage Association

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement spl ...

}.

Sewall became involved in the state fight for women's right to vote in 1880, when the Indianapolis suffragists lobbied the Indiana General Assembly

The Indiana General Assembly is the state legislature, or legislative branch, of the state of Indiana. It is a bicameral legislature that consists of a lower house, the Indiana House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Indiana Senate. ...

to pass a bill that would give Indiana women the right to vote on an equal basis with men. The suffrage supporters, including Sewall, were successful in getting the Indiana Senate

The Indiana Senate is the upper house of the Indiana General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Indiana. The Senate is composed of 50 members representing an equal number of constituent districts. Senators serve four-year terms ...

and the Indiana House of Representatives

The Indiana House of Representatives is the lower house of the Indiana General Assembly, the state legislature of the U.S. state of Indiana. The House is composed of 100 members representing an equal number of constituent districts. House memb ...

to adopt a suffrage amendment to the state constitution in 1881, but state law required amendments to the state constitution to be passage at two consecutive legislative sessions. Indiana's suffrage groups worked statewide to secure passage of the amendment in the 1883 legislative session. The House resolution passed on February 20, 1883, but the Senate refused to act on it. Frustrated with the Indiana legislature's failure to amend the state constitution, Sewall turned her efforts to securing voting rights for women at the national level.

National and international affiliations

Sewall first arrived on the national scene in 1878, when she gave a speech at the National Woman Suffrage Association's convention inRochester, New York

Rochester () is a City (New York), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York, the county seat, seat of Monroe County, New York, Monroe County, and the fourth-most populous in the state after New York City, Buffalo, New York, Buffalo, ...

, as a representative of the Indianapolis Equal Suffrage Society. Over the next three decades Sewall was actively involved in the NWSA's efforts to secure voting rights for women. During Sewall's tenure as chairperson of the NWSA's executive committee from 1882 to 1890, the NWSA and the American Woman Suffrage Association, the two national suffrage organizations, combined into the National American Woman Suffrage Association

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National ...

.

In 1887, as chairman of the NWSA's executive committee, Sewall directed the organization's plans to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Methodist Church ...

of 1848. The meeting was held in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

in 1888, and attracted delegates from the United States and Europe.Stephens, p. 282. Although Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony supported the idea of an international suffrage association, little was accomplished until Sewall's presentation at the NWSA's meeting in March 1888. Her idea was to form national and international councils of women's groups that would to bring women together for regular gatherings to discuss various topics beyond suffrage. Forty-nine delegates representing fifty-three national women's organizations approved the establishment of a fifteen-member committee that included Clara Barton

Clarissa Harlowe Barton (December 25, 1821 – April 12, 1912) was an American nurse who founded the American Red Cross. She was a hospital nurse in the American Civil War, a teacher, and a patent clerk. Since nursing education was not then very ...

, Frances Willard

Frances Elizabeth Caroline Willard (September 28, 1839 – February 17, 1898) was an American educator, temperance reformer, and women's suffragist. Willard became the national president of Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1879 an ...

, Antoinette Brown Blackwell

Antoinette Louisa Brown, later Antoinette Brown Blackwell (May 20, 1825 – November 5, 1921), was the first woman to be ordained as a mainstream Protestant minister in the United States. She was a well-versed public speaker on the paramount iss ...

, Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe (; May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American author and poet, known for writing the " Battle Hymn of the Republic" and the original 1870 pacifist Mother's Day Proclamation. She was also an advocate for abolitionism ...

, Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

, and Sewall.

"In the 1890s, Sewall carried her feminist interests even further abroad" to successfully lead efforts to organize national and international confederations of women. Sewall traveled throughout Europe to encourage women's groups to establish a national council within each country. The national groups were eligible to join the International Council of Women. Sewall served as president of the National Council of Women for the United States from 1897 to 1899 and was president of the International Council of Women from 1899 to 1904.James, James, and Boyer, pp. 269–70. The national and international councils reached their peak during Sewall's lifetime. When the National American Woman Suffrage Association joined the National Council of Women, Sewall merged her involvement with the councils with her activities in the woman's suffrage movement.

Sewall obtained permission to hold the World's Congress of Representative Women

The World's Congress of Representative Women was a week-long convention for the voicing of women's concerns, held within The Woman's Building (Chicago), The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition (Chicago, May 1893). At 81 meetings, ...

, the first meeting of the International Council of Women, in conjunction with the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordi ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

in 1893. Sewall struggled with other leaders over control of the gathering. Bertha Palmer

Bertha Matilde Palmer (; May 22, 1849 – May 5, 1918) was an American businesswoman, socialite, and philanthropist.

Early life

Born as Bertha Matilde Honoré in Louisville, Kentucky, her father was businessman Henry Hamilton Honoré. Known wi ...

, president of the fair's Board of Lady Managers and president of the woman's branch of the World’s Congress Auxiliary's, and Ellen Henrotin, vice president of the auxiliary’s woman's branch, viewed Sewall as a radical feminist and resented the implication that the National Council of Women was organizing the World's Congress. Sewall threatened to resign, but remained with the organizing group, who hosted a successful meeting. The weeklong World's Congress brought 126 national women’s organizations together from around the world. Its estimated attendance was more than 150,000.Stephens, p. 284.

Sewall's work in establishing the National Council of Women in the United States led to her involvement in founding the General Federation of Women's Clubs

The General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC), founded in 1890 during the Progressive Movement, is a federation of over 3,000 women's clubs in the United States which promote civic improvements through volunteer service. Many of its activities ...

. The federation's constitution was ratified in 1890. Sewall attended its first organizational meeting in February 1891, and helped to write its bylaws, but she was disappointed when the new organization decided not to join the National Council of Women. After serving as the first vice-president of the federation, her interest in the group gradually declined, and she turned her efforts toward the National Council of Women and other reform issues. U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

appointed Sewall as U.S. representative of women to the Exposition Universelle (1900)

The Exposition Universelle of 1900, better known in English as the 1900 Paris Exposition, was a world's fair held in Paris, France, from 14 April to 12 November 1900, to celebrate the achievements of the past century and to accelerate developmen ...

in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

.

Later years

Disappointed at the amount she had received from Weaver, after Sewall's retirement from the Girls' Classic School in 1907 and her departure from Indianapolis, she depended on income from public lectures on women's rights and world peace. In 1916 Sewall retired from public life, and wrote a book about her experiences in spiritualism.Eliot, Maine

Eliot is a town in York County, Maine, United States. Originally settled in 1623, it was formerly a part of Kittery, Maine, to its east. After Kittery, it is the next most southern town in the state of Maine, lying on the Piscataqua River across f ...

, where there was "a center on the subject" of spiritualism, and Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

, became her home base. Sewall returned to Indianapolis in October 1919, and died the following year.

Peace advocate

During the last fifteen years of her life Sewall combined her activities her interests in the women's movement and working for world peace. Sewall was active in the American Peace Society, and became chairperson of the International Council of Women's standing committee on peace and arbitration in 1904. She persuaded the National Council of Women for the United States and the International Council of Women to adopt peace programs in 1907 and 1909, respectively. The International Council of Women became a "driving force" in the peace movement worldwide. During the four Peace Congresses held between 1904 and 1911 Sewall was either a speaker or guest of honor, who represented the nearly eight million women of the International Council. In July 1915 Sewall attended the Panama-Pacific International Exposition inSan Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, where she was chairperson and organizer of the International Conference of Women Workers to Promote Permanent Peace. The conference attracted five hundred delegates from the United States and eleven other countries.

In December 1915 Sewall joined Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

and others on Ford's Peace Ship

The Peace Ship was the common name for the ocean liner ''Oscar II'', on which American industrialist Henry Ford organized and launched his 1915 amateur peace mission to Europe; Ford chartered the ''Oscar II'' and invited prominent peace activists t ...

, an unofficial peace expedition aboard the ''Oscar II'' in an unsuccessful attempt to halt the war in Europe and bring the American troops home by year's end. Sewall was one of sixty delegates on the trip, which left Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,690 i ...

, bound for Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

, on December 4. Sewall hoped the effort would gain public attention to the cause for peace and strengthen the peace movement's resolve, but it received a mixed reaction from the press. After traveling through Norway, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

, Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

, and the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, the group concluded their trip and departed for the United States in January 1916. Although some argued the trip served a useful purpose by bringing together idealists and journalists to help popularize the peace movement, others considered it a failure. Sewall was more optimistic; she thought it helped advance the hope for lasting peace. Following her return to the United States, Sewall toured the public lecture circuit, but soon disappeared from public life, possibly for health reasons (she was seventy-two) or was embarrassed by the trip's outcome, and turned to other pursuits.

Spiritualist

Sewall was a member of a Unitarian church in Indianapolis, but psychic research had been an interest since the 1880s. Sewall converted tospiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (when not lowercase) ...

after attending a chautauqua

Chautauqua ( ) was an adult education and social movement in the United States, highly popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Chautauqua assemblies expanded and spread throughout rural America until the mid-1920s. The Chautauqua bro ...

meeting at Lily Dale, New York

Lily Dale is a hamlet, connected with the Spiritualist movement, located in the Town of Pomfret on the east side of Cassadaga Lake, next to the Village of Cassadaga. Located in southwestern New York State, it is one hour southwest of Buffalo, ...

, in 1897.Boomhower, p. 115–16. At Lily Dale Sewall met with a spiritualist medium

Medium may refer to:

Science and technology

Aviation

*Medium bomber, a class of war plane

*Tecma Medium, a French hang glider design

Communication

* Media (communication), tools used to store and deliver information or data

* Medium of ...

, who asked her to write several questions on bits of paper that Sewall claimed never left her hands. Sewall then selected a slate that was wiped clear and tied with her own handkerchief. When Sewall later opened the slate at her hotel, expecting it to be blank inside, she found responses to her questions were legibly written on the slate. From that time she claimed to have had regular communications with her deceased husband, Theodore, and communicated with other deceased family members, a noted Russian pianist named Anton Rubinstein

Anton Grigoryevich Rubinstein ( rus, Антон Григорьевич Рубинштейн, r=Anton Grigor'evič Rubinštejn; ) was a Russian pianist, composer and conductor who became a pivotal figure in Russian culture when he founded the Sai ...

, and Père Condé, who was a medieval priest and physician from France.Stephens, p. 294.

Following Sewall's retirement from public life in 1916, she wrote a book describing her psychic experiences. ''Neither Dead Nor Sleeping'' (1920) was published two months prior to her death in July 1920. Indiana author Booth Tarkington

Newton Booth Tarkington (July 29, 1869 – May 19, 1946) was an American novelist and dramatist best known for his novels ''The Magnificent Ambersons'' (1918) and '' Alice Adams'' (1921). He is one of only four novelists to win the Pulitze ...

, who wrote the introduction to her book, assisted in getting Bobbs-Merrill Company

The Bobbs-Merrill Company was a book publisher located in Indianapolis, Indiana.

Company history

The company began in 1850 October 3 when Samuel Merrill bought an Indianapolis bookstore and entered the publishing business. After his death in 1 ...

to publish it. The book received some positive reviews at the time of its publication. One ''New York Times Book Review'' described it as "striking" and "amazing is hardly too strong of a word." Other reviewers praised her sincerity.

The book's publication surprised many people, especially those who knew Sewall, because it revealed a previously unknown side of her life that she had concealed from the public for nearly twenty-five years. Sewall provided two reasons for concealing her involvement in the spiritualism movement until the publication of her book. She claimed those who contacted her from the spirit world told her keep quiet, and the few living friends who did know about her communications with the dead thought she had imagined them. Sewall explained her intent in publishing the book was to provide others with the "comfort of knowing the simplicity and naturalness of the life into which they passed" after their life on earth ended.

Death and legacy

Sewall died on July 22, 1920, of "chronic parenchymatous nephritis" (kidney disease) at St. Vincent's Hospital, Indianapolis, at the age of seventy-six. Her funeral was held at All Souls Unitarian Church in Indianapolis. She is buried atCrown Hill Cemetery

Crown Hill Cemetery is a historic rural cemetery located at 700 West 38th Street in Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana. The privately owned cemetery was established in 1863 at Strawberry Hill, whose summit was renamed "The Crown", a high poi ...

, Indianapolis, beside her second husband, Theodore.Boomhower, p. 133.

Sewall was known for her service to humanity, especially the causes of education, women's rights, and world peace. Her greatest contributions to reform came through her efforts to organize and lead the National Council of Women in the United States and International Council of Women at the turn of the twentieth century. Sewall did not live to see the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which was ratified in August 1920, a month after her death.

Sewall's legacy of civic-mindedness remains evident in the Indianapolis organizations she helped to establish, most notably the Indianapolis Woman's Club, the Indianapolis Propylaeum, the Indianapolis Museum of Art, and the John Herron Art Institute.

In later years the publication of Sewall's book, ''Neither Dead Nor Sleeping'' (1920), and her beliefs on spiritualism overshadowed her thirty-year career in education and longtime support of women's rights.

Works

Books

* ''The Higher Education of Women'' (1915) * ''The Woman Suffrage Movement in Indiana'' (1915) * ''Women, World War and Permanent Peace'' (1915) * ''Neither Dead Nor Sleeping'' (1920)Other

* "Culture—Its Fruit and Its Price" * Sewall also edited a woman's column for the ''Indianapolis Times''.Honors and awards

* In 1893 the U.S. government presented Sewall an award for her work in organizing the World's Congress of Representative Women at Chicago. * In May 1923 the Sewall Memorial Torches, a pair of bronze lampposts, were dedicated to her memory at the John Herron Art Institute (the present-day Herron High School) in Indianapolis. * In 2005 the Propylaeum Historical Foundation established the May Wright Sewall Leadership Award to recognize other Indianapolis women for their community service. *In 2019, the Indiana Historical Bureau added an historical marker.See also

*List of suffragists and suffragettes

This list of suffragists and suffragettes includes noted individuals active in the worldwide women's suffrage movement who have campaigned or strongly advocated for women's suffrage, the organisations which they formed or joined, and the public ...

* List of women's rights activists

This article is a list of notable women's rights activists, arranged alphabetically by modern country names and by the names of the persons listed.

Afghanistan

* Amina Azimi – disabled women's rights advocate

* Hasina Jalal – women's empowerm ...

* Timeline of women's suffrage in the United States

This timeline highlights milestones in women's suffrage in the United States, particularly the right of women to vote in elections at federal and state levels.

1780s

180px, Susan B. Anthony, 1870

1789: The Constitution of the United S ...

* History of feminism

The history of feminism comprises the narratives (chronological or thematic) of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * Sewall, May Wright, "Culture—Its Fruit and Its Price" in * *External links

May Wright Sewall Papers

Indianapolis Marion County Public Library

May Wright Sewall Papers crowdsourcing transcription project

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sewall, Mary Wright 1844 births 1920 deaths People from Indianapolis People from Greenfield, Wisconsin American feminists American suffragists People from Plainwell, Michigan American Unitarians Indianapolis Museum of Art people