Max Steenbeck on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

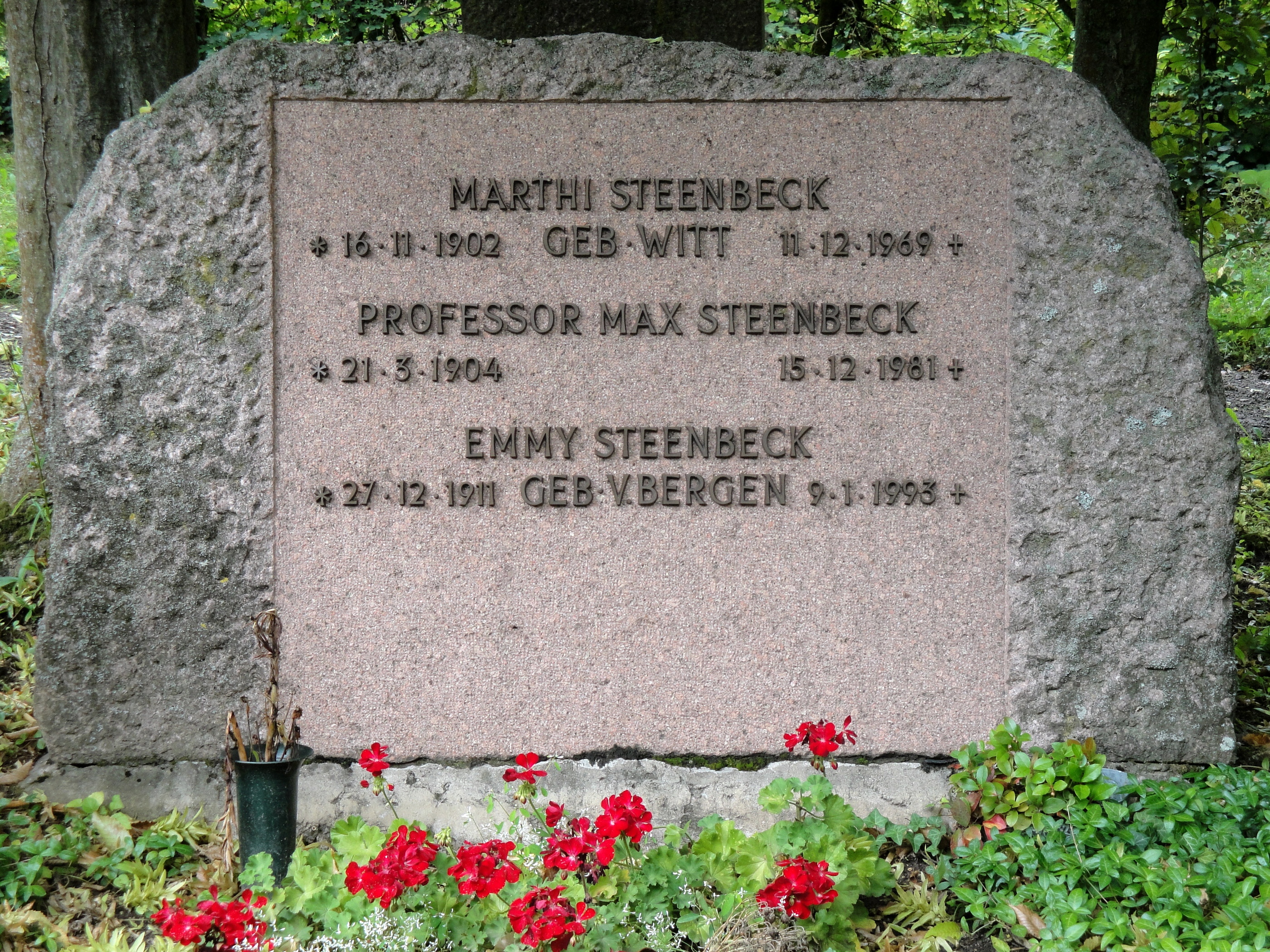

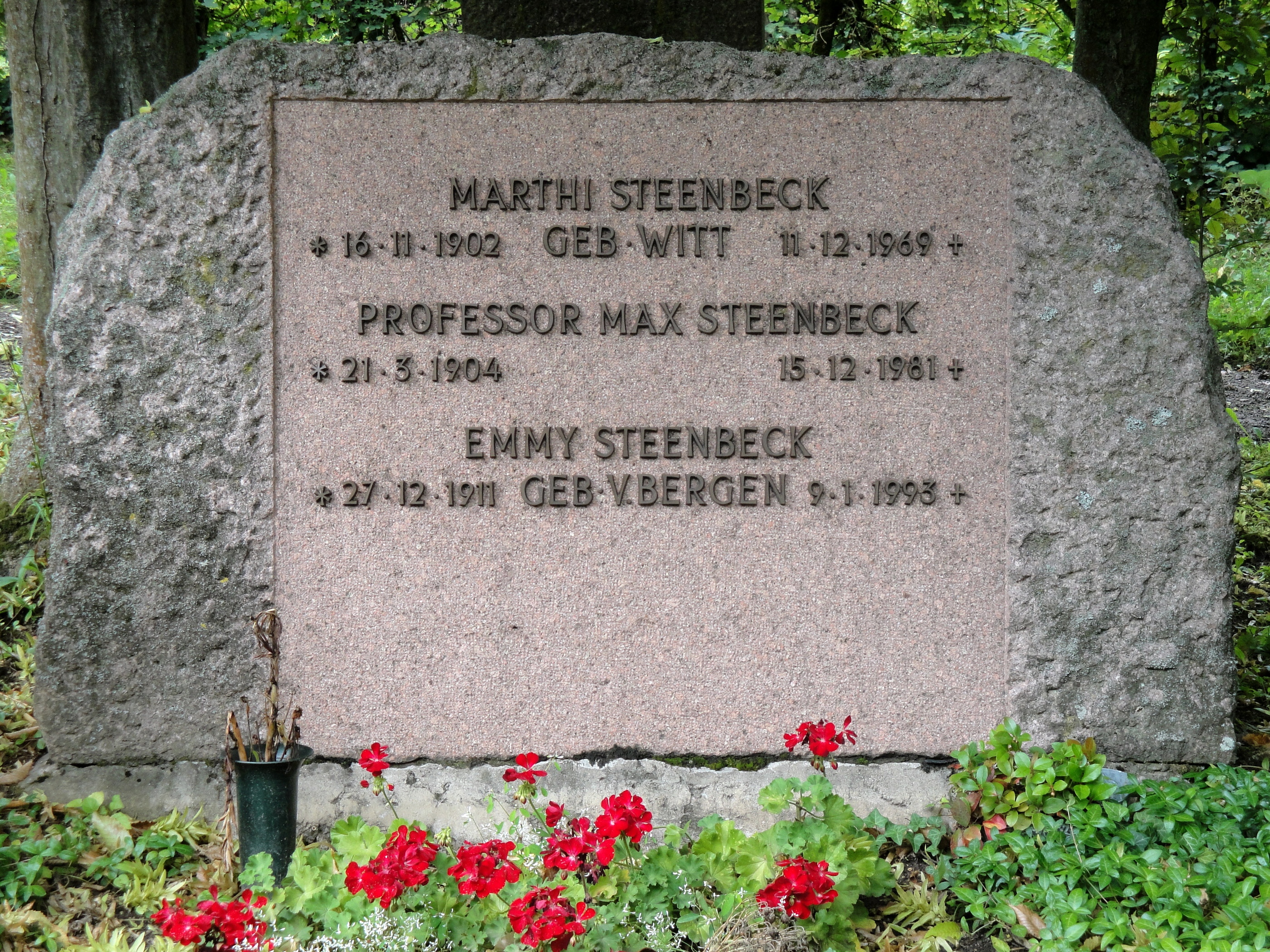

Max Christian Theodor Steenbeck (21 March 1904 – 15 December 1981) was a German physicist who worked at the '' Siemens-Schuckertwerke'' in his early career, during which time he invented the

Max Christian Theodor Steenbeck (21 March 1904 – 15 December 1981) was a German physicist who worked at the '' Siemens-Schuckertwerke'' in his early career, during which time he invented the

In 1956, Steenbeck became an ordinarius professor of plasma physics at the

In 1956, Steenbeck became an ordinarius professor of plasma physics at the Max-Steenbeck-Gymnasium

– Cottbus.

(2000)

The author has been a group leader at the Institute of Technical Physics of the Russian Federal Nuclear Centre in

Lawrence and His Laboratory

- ''II — A Million Volts or Bust'' in Heilbron, J. L., and Robert W. Seidel ''Lawrence and His Laboratory: A History of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory', Volume I.'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000)

Tracking the technology

– Nuclear Engineering International, 31 August 2004

– William J. Broad ''Slender and Elegant, It Fuels the Bomb'', ''New York Times'' March 23, 2004

Max Christian Theodor Steenbeck (21 March 1904 – 15 December 1981) was a German physicist who worked at the '' Siemens-Schuckertwerke'' in his early career, during which time he invented the

Max Christian Theodor Steenbeck (21 March 1904 – 15 December 1981) was a German physicist who worked at the '' Siemens-Schuckertwerke'' in his early career, during which time he invented the betatron

A betatron is a type of cyclic particle accelerator. It is essentially a transformer with a torus-shaped vacuum tube as its secondary coil. An alternating current in the primary coils accelerates electrons in the vacuum around a circular path. Th ...

in 1934. He was taken to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and he contributed to the Soviet atomic bomb project

The Soviet atomic bomb project was the classified research and development program that was authorized by Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union to develop nuclear weapons during and after World War II.

Although the Soviet scientific community dis ...

. In 1955, he returned to East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

to continue a career in nuclear physics

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

.

Early life

Steenbeck was born inKiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the J ...

. He studied physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

and chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

at the University of Kiel

Kiel University, officially the Christian-Albrecht University of Kiel, (german: Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, abbreviated CAU, known informally as Christiana Albertina) is a university in the city of Kiel, Germany. It was founded in ...

from 1922 to 1927. He completed his thesis on x-rays

An X-ray, or, much less commonly, X-radiation, is a penetrating form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation. Most X-rays have a wavelength ranging from 10 Picometre, picometers to 10 Nanometre, nanometers, corresponding to frequency, ...

under Walther Kossel

Walther Ludwig Julius Kossel (4 January 1888 – 22 May 1956) was a German physicist known for his theory of the chemical bond (ionic bond/octet rule), Sommerfeld–Kossel displacement law of atomic spectra, the Kossel-Stranski model for crystal ...

; he submitted the thesis in 1927/1928 and his doctorate was awarded in January 1929.

While a student at Kiel, he formulated the concept of the cyclotron

A cyclotron is a type of particle accelerator invented by Ernest O. Lawrence in 1929–1930 at the University of California, Berkeley, and patented in 1932. Lawrence, Ernest O. ''Method and apparatus for the acceleration of ions'', filed: Janu ...

.

Career

Early years

From 1927 to 1945, Steenbeck was a physicist at the '' Siemens-Schuckertwerke'' inBerlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

. From 1934, he was a laboratory director, and it was in that year that he submitted a patent for the betatron

A betatron is a type of cyclic particle accelerator. It is essentially a transformer with a torus-shaped vacuum tube as its secondary coil. An alternating current in the primary coils accelerates electrons in the vacuum around a circular path. Th ...

. In 1943, he was appointed technical director of a static converter plant at Siemens, conducting research in gas-discharge physics. Additionally, at his plant, he was head of the Volkssturm

The (; "people's storm") was a levée en masse national militia established by Nazi Germany during the last months of World War II. It was not set up by the German Army, the ground component of the combined German ''Wehrmacht'' armed forces, ...

(people's army), the organised civilian resistance at the plant, which was to, as a last resort, defend the territory.

In the Soviet Union

At the close ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

he was arrested by the Soviet military forces, and he was incarcerated at a concentration camp in Poznań

Poznań () is a city on the River Warta in west-central Poland, within the Greater Poland region. The city is an important cultural and business centre, and one of Poland's most populous regions with many regional customs such as Saint John ...

. He wrote to the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

and explained his scientific background. Eventually, he was taken to recuperate at the dacha Opalicha at the end of 1945, after which he was sent to work at Manfred von Ardenne’s Institute A, in Sinop, a suburb of Sukhumi

Sukhumi (russian: Суху́м(и), ) or Sokhumi ( ka, სოხუმი, ), also known by its Abkhaz name Aqwa ( ab, Аҟәа, ''Aqwa''), is a city in a wide bay on the Black Sea's eastern coast. It is both the capital and largest city of ...

. He headed a group working on both electromagnetic and centrifugal isotope separation

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research (e.g. in chemistry where atoms of "marker" n ...

for the enrichment of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element with the symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium is weak ...

, with the latter having the highest priority. Steenbeck and his group were pioneers in the development of supercritical centrifuges. Steenbeck’s group, at its largest, included from 60 to 100 German and Russian personnel. Steenbeck was kept in the Soviet Union until 1956, when he went to East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

.

While Steenbeck developed the theory of the centrifugal isotope separation process, Gernot Zippe, an Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

n, headed the experimental effort in Steenbeck’s group. Zippe, a POW

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war ...

from the Krasnogorsk camp, joined the group in the summer of 1946. Zippe returned to Germany in 1956. In 1957, he attended a conference on centrifugal isotope separation; it was then that he realized how advanced the work had been in Steenbeck’s group, and Zippe then applied for a patent on short-bowl centrifuge technology, known as the Zippe-type centrifuge

The Zippe-type centrifuge is a gas centrifuge designed to enrich the rare fissile isotope uranium-235 (235U) from the mixture of isotopes found in naturally occurring uranium compounds. The isotopic separation is based on the slight difference in ...

. He was invited to repeat the experiments at the University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. Founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson, the university is ranked among the top academic institutions in the United S ...

. Shortly after completing the work, at the request of the United States, all centrifuge research in Germany became classified on August 1, 1960. The work of Steenbeck and Zippe shaped Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

an and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

ese enrichment processes and later those in Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

and Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

.

Steenbeck and Zippe, before being allowed to leave the Soviet Union, were put into quarantine in the second half of 1952. During the quarantine period, they only performed unclassified work. First they went to Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, after which they worked in the Institute of Semiconductors of the Academy of Sciences in Kiev

Kyiv, also spelled Kiev, is the capital and most populous city of Ukraine. It is in north-central Ukraine along the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2021, its population was 2,962,180, making Kyiv the List of European cities by populat ...

. They both left the Soviet Union in 1956.

Return to (East) Germany

In 1956, Steenbeck became an ordinarius professor of plasma physics at the

In 1956, Steenbeck became an ordinarius professor of plasma physics at the Friedrich Schiller University of Jena

The University of Jena, officially the Friedrich Schiller University Jena (german: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, abbreviated FSU, shortened form ''Uni Jena''), is a public research university located in Jena, Thuringia, Germany.

The un ...

, and, from 1956 to 1959, he was also director of the Institute for Magnetic Materials at Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, while the city itself has a popu ...

. From 1958 to 1969, he was director of the German Academy of Science Institute for Magnetohydrodynamics

Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD; also called magneto-fluid dynamics or hydromagnetics) is the study of the magnetic properties and behaviour of electrically conducting fluids. Examples of such magnetofluids include plasmas, liquid metals, ...

, also in Jena. From 1957 to 1963, he was the head of the Technological Science Bureau on Reactor Construction, in Berlin. From 1962 to 1964, he was vice-president and in 1965 president of the German Academy of Science. In 1970, he was president of the East German Committee on European Security. In 1976, Steenbeck was honorary president of the East German Research Council. He died in East Berlin

East Berlin was the ''de facto'' capital city of East Germany from 1949 to 1990. Formally, it was the Allied occupation zones in Germany, Soviet sector of Berlin, established in 1945. The American, British, and French sectors were known as ...

.

The ''Max-Steenbeck Gymnasium'' in Cottbus, an academic high school offering extended mathematical-scientific-technical training, was named in his honour. .– Cottbus.

Selected literature

* W. Kossel and M. Steenbeck ''Absolute Messung des Quantenstroms im Röntgenstrahl'', ''Zeitschrift für Physik'' Volume 42, Numbers 11-12, 832-834 (1927). The authors were cited as being from the ''Physikalisches Institut'', Kiel. The article was received on 14. March 1927. *Alfred von Engel and Max Steenbeck ''On the Gas-Temperature in the Positive Column of an Arc'' ''Phys. Rev. '' Volume 37, Issue 11, 1554 - 1554 (1931). The authors were cited as being at ''Wissenschaftliche Abteilung, der Siemens-Schuckertwerke A.-G.'', Berlin. The article was received on 28 April 1931.Books

*Max Steenbeck ''Probleme und Ergebnisse der Elektro- und Magnetohydrodynamik'' (Akademie-Verl., 1961) *Max Steenbeck, Fritz Krause, and Karl-Heinz Rädler ''Elektrodynamische Eigenschaften turbulenter Plasmen'' (Akademie-Verl., 1963) *Max Steenbeck ''Wilhelm Wien und sein Einfluss auf die Physik seiner Zeit'' (Akademie-Verl., 1964) *Max Steenbeck ''Die wissenschaftlich-technische Entwicklung und Folgerungen für den Lehr- und Lernprozess im System der Volksbildung der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik'' (VEB Verl. Volk u. Wissen, 1964) *Max Steenbeck ''Wachsen und Wirken der sozialistischen Persönlichkeit in der wissenschaftlich-technischen Revolution'' (Dt. Kulturbund, 1968) *Max Steenbeck ''Impulse und Wirkungen. Schritte auf meinem Lebensweg.'' (Verlag der Nation, 1977)Bibliography

*Albrecht, Ulrich, Andreas Heinemann-Grüder, and Arend Wellmann ''Die Spezialisten: Deutsche Naturwissenschaftler und Techniker in der Sowjetunion nach 1945'' (Dietz, 1992, 2001) * Barwich, Heinz and Elfi Barwich ''Das rote Atom'' (Fischer-TB.-Vlg., 1984) *Heinemann-Grüder, Andreas ''Keinerlei Untergang: German Armaments Engineers during the Second World War and in the Service of the Victorious Powers'' in Monika Renneberg and Mark Walker (editors) ''Science, Technology and National Socialism'' 30-50 (Cambridge, 2002 paperback edition) *Hentschel, Klaus (editor) and Ann M. Hentschel (editorial assistant and translator) ''Physics and National Socialism: An Anthology of Primary Sources'' (Birkhäuser, 1996) *Holloway, David ''Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy 1939 – 1956'' (Yale, 1994) *Naimark, Norman M. ''The Russians in Germany: A History of the Soviet Zone of Occupation, 1945-1949'' (Hardcover - Aug 11, 1995) Belknap *Oleynikov, Pavel V. ''German Scientists in the Soviet Atomic Project'', ''The Nonproliferation Review'' Volume 7, Number 2, 1 – 30(2000)

The author has been a group leader at the Institute of Technical Physics of the Russian Federal Nuclear Centre in

Snezhinsk

Snezhinsk ( rus, Сне́жинск, p=ˈsnʲeʐɨnsk) is a closed town in Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia. Population:

History

The settlement began in 1955 as Residential settlement number 2, a name which it had until 1957 when it received town ...

(Chelyabinsk-70).

*Riehl, Nikolaus and Frederick Seitz

Frederick Seitz (July 4, 1911 – March 2, 2008) was an American physicist and a pioneer of solid state physics and lobbyist.

Seitz was the 4th president of Rockefeller University from 1968–1978, and the 17th president of the United States Nat ...

''Stalin’s Captive: Nikolaus Riehl and the Soviet Race for the Bomb'' (American Chemical Society and the Chemical Heritage Foundations, 1996) . This book is a translation of Nikolaus Riehl’s book ''Zehn Jahre im goldenen Käfig (Ten Years in a Golden Cage)'' (Riederer-Verlag, 1988); Seitz has written a lengthy introduction to the book. This book is a treasure trove with its 58 photographs.

External links

Lawrence and His Laboratory

- ''II — A Million Volts or Bust'' in Heilbron, J. L., and Robert W. Seidel ''Lawrence and His Laboratory: A History of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory', Volume I.'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000)

Tracking the technology

– Nuclear Engineering International, 31 August 2004

– William J. Broad ''Slender and Elegant, It Fuels the Bomb'', ''New York Times'' March 23, 2004

Notes

{{DEFAULTSORT:Steenbeck, Max 1904 births 1981 deaths 20th-century German physicists Scientists from Kiel People from the Province of Schleswig-Holstein East German scientists German expatriates in the Soviet Union Foreign Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Recipients of the Lomonosov Gold Medal Members of the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin Volkssturm personnel