Matthew Cradock (died 1590s) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

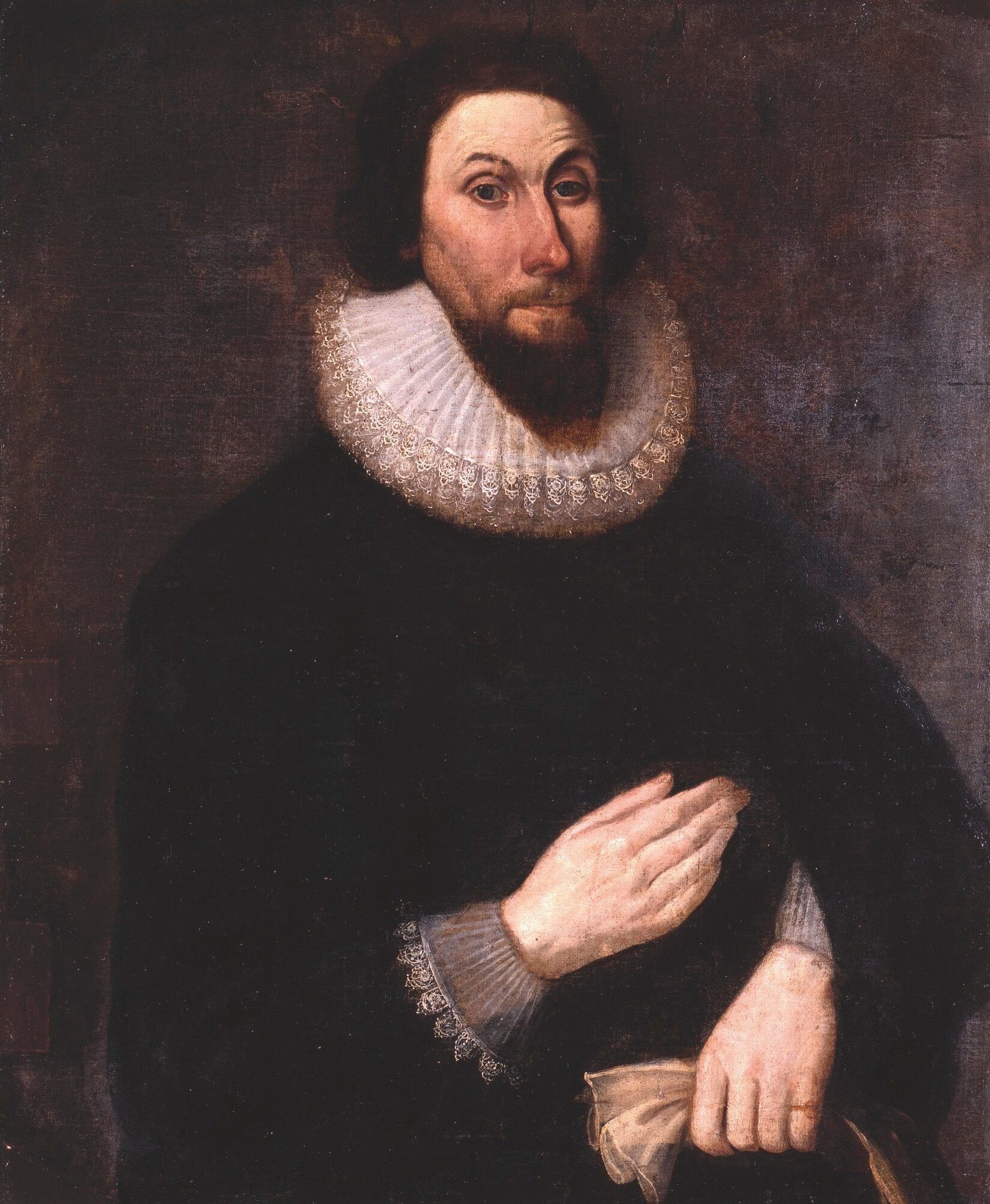

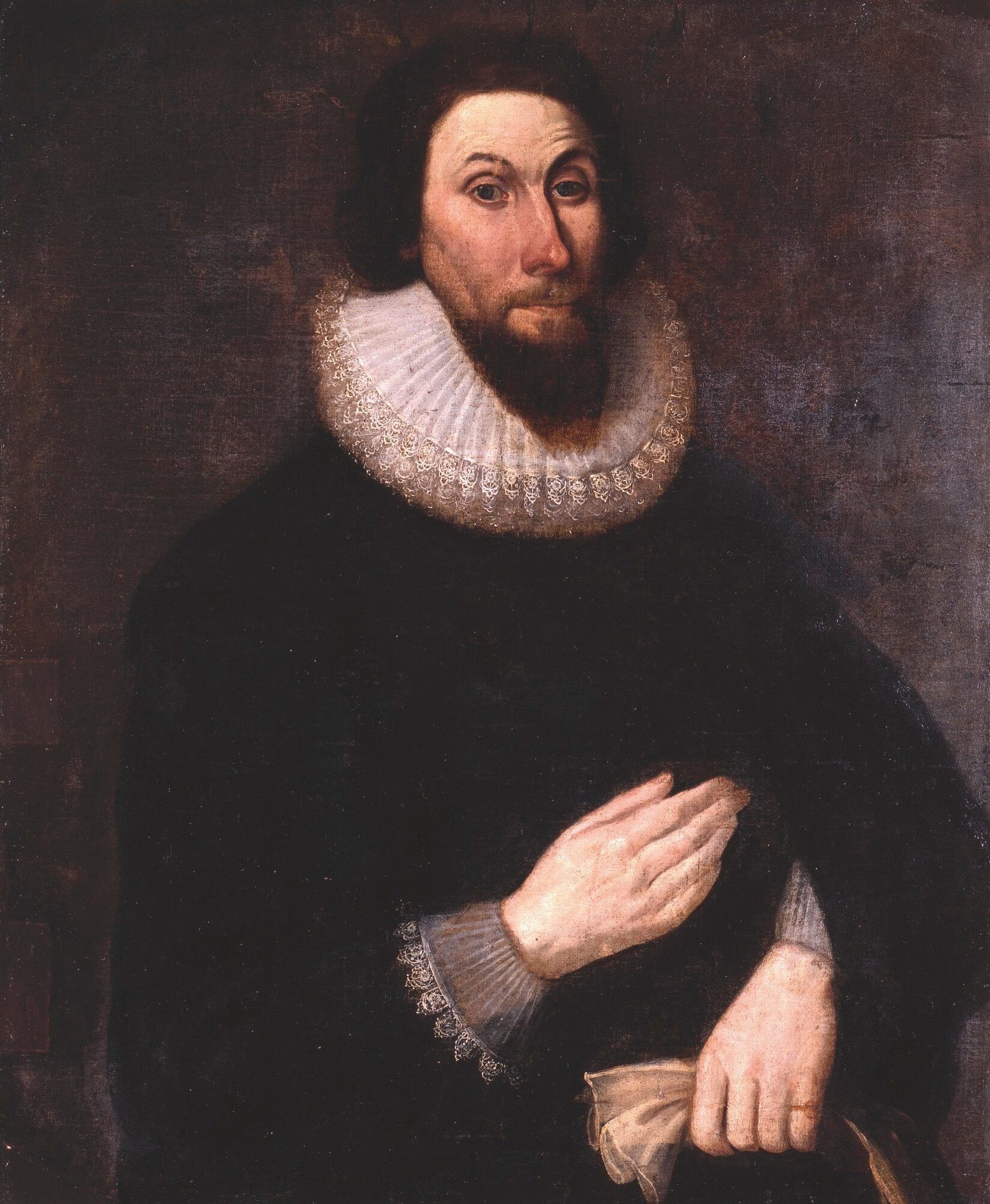

Matthew Cradock (also spelled Craddock and Craddocke; died 27 May 1641) was a London merchant, politician, and the first governor of the

Nothing is known of Matthew Cradock's early life. He was from a

Nothing is known of Matthew Cradock's early life. He was from a

The company's land grant was not without problems, because it overlapped a grant that had previously been acquired by John Oldham. Cradock wrote to Endecott in early 1629, warning him about the issue, suggesting that he settle colonists in the claimed area and also that he treat well the Old Planters (the surviving colonists from the failed Dorchester Company settlement). Cradock also recommended the colonists work on building ships and other profit-making activities. Later in 1629 another small fleet sailed for the colony; on board, in addition to Puritan settlers, were skilled craftsmen of all types who were engaged in Cradock's businesses.

The company, in order to protect its claims, acquired a royal charter in 1629, under which Cradock was named the colony's governor in London, while Endecott governed in the colony. In that same year, financial instability in the government caused by King Charles I's desire to prosecute a war with Scotland led the company's investors to fear their investment might be at risk. Cradock, at a shareholder meeting in July 1629, suggested that the company transfer its governance to the colony itself, something that was only possible because the charter did not specify where the company's shareholder meetings were to be held. However, some investors (Cradock among them) did not want to emigrate to the colony, so a means to buy out those investors needed to be devised. After negotiating through the summer, an agreement was reached on 29 August 1629. It called for those shareholders who were emigrating to buy out those that remained in England after seven years; the latter would also receive a share of some of the colony's business activities, including the

The company's land grant was not without problems, because it overlapped a grant that had previously been acquired by John Oldham. Cradock wrote to Endecott in early 1629, warning him about the issue, suggesting that he settle colonists in the claimed area and also that he treat well the Old Planters (the surviving colonists from the failed Dorchester Company settlement). Cradock also recommended the colonists work on building ships and other profit-making activities. Later in 1629 another small fleet sailed for the colony; on board, in addition to Puritan settlers, were skilled craftsmen of all types who were engaged in Cradock's businesses.

The company, in order to protect its claims, acquired a royal charter in 1629, under which Cradock was named the colony's governor in London, while Endecott governed in the colony. In that same year, financial instability in the government caused by King Charles I's desire to prosecute a war with Scotland led the company's investors to fear their investment might be at risk. Cradock, at a shareholder meeting in July 1629, suggested that the company transfer its governance to the colony itself, something that was only possible because the charter did not specify where the company's shareholder meetings were to be held. However, some investors (Cradock among them) did not want to emigrate to the colony, so a means to buy out those investors needed to be devised. After negotiating through the summer, an agreement was reached on 29 August 1629. It called for those shareholders who were emigrating to buy out those that remained in England after seven years; the latter would also receive a share of some of the colony's business activities, including the

In 1640 Cradock was an auditor of the

In 1640 Cradock was an auditor of the

Charter of Massachusetts Bay

a copy in the

A Peculiar Plantation: 17th Century Medford

extract from ''Medford on the Mystic'', published by The Medford Historical Society, April 1980. {{DEFAULTSORT:Cradock, Matthew Year of birth missing 1641 deaths English businesspeople Levant Company Directors of the British East India Company West Indies merchants Colonial governors of Massachusetts Roundheads 17th-century English merchants Members of the Parliament of England for the City of London English MPs 1640 (April) English MPs 1640–1648

Massachusetts Bay Company

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. Founded in 1628, it was an organization of Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

businessmen that organized and established the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as the ...

. Although he never visited the colony, Cradock owned property and businesses there, and he acted on its behalf in London. His business and trading empire encompassed at least 18 ships, and extended from the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

and North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

to Europe and the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

. He was a dominant figure in the tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

trade.

Cradock was a strong supporter of the Parliamentary cause in the years leading up to the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

. He opposed royalist conservatism in the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

and, as a member of the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septem ...

, supported the '' Root and Branch'' attempts to radically reform the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. He played a leading role in the Protestation of 1641

The Protestation of 1641 was an attempt to avert the English Civil War. Parliament passed a bill on 3 May 1641 requiring those over the age of 18 to sign the Protestation, an oath of allegiance to King Charles I and the Church of England, as a way ...

, and died not long after.

Early life and business

Nothing is known of Matthew Cradock's early life. He was from a

Nothing is known of Matthew Cradock's early life. He was from a Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands Cou ...

family; a cousin, also named Matthew Cradock

Matthew Cradock (also spelled Craddock and Craddocke; died 27 May 1641) was a London merchant, politician, and the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Company. Founded in 1628, it was an organization of Puritan businessmen that organized a ...

, was mayor of Stafford, and built a mansion on the site of Caverswall Castle

Caverswall Castle is a privately owned early-17th-century English mansion built in a castellar style upon the foundations and within the walls of a 13th-century castle, in Caverswall, Staffordshire. It is a Grade I listed building. The castle i ...

, Staffordshire. Although his father was a cleric, his grandfather was a merchant, and other family members were involved in trade.Brenner, p. 137 Cradock was twice married. By his first wife Damaris he had a daughter, also named Damaris; by his second wife, Rebeccah, he had three children that apparently did not survive. Rebeccah survived him, but the children are not mentioned in his will.

In 1606 he was an apprentice to William Cockayne

Sir William Cockayne (Cokayne) (1561 – 20 October 1626) was a seventeenth-century merchant, alderman, and Lord Mayor of the City of London.

Life

He was the second son of William Cokayne of Baddesley Ensor, Warwickshire, merchant of London, so ...

at the Skinners' Company, then a major London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

shipping firm.Andrews, p. 90 He probably began trading with northwestern Europe, but eventually expanded his business to the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

. Cradock joined the Levant Company

The Levant Company was an English chartered company formed in 1592. Elizabeth I of England approved its initial charter on 11 September 1592 when the Venice Company (1583) and the Turkey Company (1581) merged, because their charters had expired, ...

in 1627, and in 1628 he purchased £2,000 of stock in the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

.Bailyn, p. 17 Cradock served as a director of the East India Company in 1629–1630 and again from 1634 until his death in 1641. Cradock used his business and personal connections to establish a lucrative trade, shipping New World tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

to the Near East and sending provisions to the colonies in North America and the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

that produced it. He is known to have been owner or part owner of 18 ships between 1627 and 1640,Andrews, p. 91 and he was one of a relatively small number of businessmen whose trade encompassed both eastern trade (to India and the Levant) and trade in European waters. By the end of the 1630s he stood at the center of one of the largest trading businesses involved in the Americas. In 1640 Cradock was a member of a group of business men who opposed the conservative royalist leadership of the East India Company, engaging in an unsuccessful attempt to reform the company's directorate.

Massachusetts Bay Company

Interest by London merchants in establishing and managing colonial settlements in North America waned after the 1624 failure of theLondon Company

The London Company, officially known as the Virginia Company of London, was a division of the Virginia Company with responsibility for colonizing the east coast of North America between latitudes 34° and 41° N.

History Origins

The territor ...

and the subsequent conversion of the Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colonial empire, English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertG ...

into a Crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

. Cradock was a notable exception; a Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

, in 1628 he made a major investment in the New England Company

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England (also known as the New England Company or Company for Propagation of the Gospel in New England and the parts adjacent in America) is a British charitable organization created to promote ...

, formed by a group of Puritan religious and business leaders to take over the assets of the failed Dorchester Company

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1630–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, the northernmost of the several colonies later reorganized as th ...

and make new ventures in the colonisation of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

. Cradock was elected the company's first governor on 13 May 1628. Not long after, the company acquired a grant of land on Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

from the Plymouth Council for New England

The Council for New England was a 17th-century English joint stock company that was granted a royal charter to found colonial settlements along the coast of North America. The Council was established in November of 1620, and was disbanded (althou ...

, and sent John Endecott

John Endecott (also spelled Endicott; before 1600 – 15 March 1664/1665), regarded as one of the Fathers of New England, was the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He serv ...

with a small group of settlers to begin the process of establishing a colony at a place now called Salem, Massachusetts

Salem ( ) is a historic coastal city in Essex County, Massachusetts, located on the North Shore of Greater Boston. Continuous settlement by Europeans began in 1626 with English colonists. Salem would become one of the most significant seaports tr ...

.

The company's land grant was not without problems, because it overlapped a grant that had previously been acquired by John Oldham. Cradock wrote to Endecott in early 1629, warning him about the issue, suggesting that he settle colonists in the claimed area and also that he treat well the Old Planters (the surviving colonists from the failed Dorchester Company settlement). Cradock also recommended the colonists work on building ships and other profit-making activities. Later in 1629 another small fleet sailed for the colony; on board, in addition to Puritan settlers, were skilled craftsmen of all types who were engaged in Cradock's businesses.

The company, in order to protect its claims, acquired a royal charter in 1629, under which Cradock was named the colony's governor in London, while Endecott governed in the colony. In that same year, financial instability in the government caused by King Charles I's desire to prosecute a war with Scotland led the company's investors to fear their investment might be at risk. Cradock, at a shareholder meeting in July 1629, suggested that the company transfer its governance to the colony itself, something that was only possible because the charter did not specify where the company's shareholder meetings were to be held. However, some investors (Cradock among them) did not want to emigrate to the colony, so a means to buy out those investors needed to be devised. After negotiating through the summer, an agreement was reached on 29 August 1629. It called for those shareholders who were emigrating to buy out those that remained in England after seven years; the latter would also receive a share of some of the colony's business activities, including the

The company's land grant was not without problems, because it overlapped a grant that had previously been acquired by John Oldham. Cradock wrote to Endecott in early 1629, warning him about the issue, suggesting that he settle colonists in the claimed area and also that he treat well the Old Planters (the surviving colonists from the failed Dorchester Company settlement). Cradock also recommended the colonists work on building ships and other profit-making activities. Later in 1629 another small fleet sailed for the colony; on board, in addition to Puritan settlers, were skilled craftsmen of all types who were engaged in Cradock's businesses.

The company, in order to protect its claims, acquired a royal charter in 1629, under which Cradock was named the colony's governor in London, while Endecott governed in the colony. In that same year, financial instability in the government caused by King Charles I's desire to prosecute a war with Scotland led the company's investors to fear their investment might be at risk. Cradock, at a shareholder meeting in July 1629, suggested that the company transfer its governance to the colony itself, something that was only possible because the charter did not specify where the company's shareholder meetings were to be held. However, some investors (Cradock among them) did not want to emigrate to the colony, so a means to buy out those investors needed to be devised. After negotiating through the summer, an agreement was reached on 29 August 1629. It called for those shareholders who were emigrating to buy out those that remained in England after seven years; the latter would also receive a share of some of the colony's business activities, including the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

. John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1587/88 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and one of the leading figures in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led t ...

, one of the shareholders who was emigrating, was elected the company's governor in October.

Winthrop sailed to Massachusetts in 1630, and the fleet carrying the colonists included two of Cradock's ships, and agents and servants of his who were to see to his commercial interests. Cradock, who took leave of the emigrants at the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

, remained behind in England. Cradock's representatives secured for him a plantation at Medford, which became a base for business operations funded by Cradock, including the colony's first shipyard. As the colony developed, Cradock's land holdings expanded to include properties in Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and borough in Suffolk, England, of which it is the county town. The town is located in East Anglia about away from the mouth of the River Orwell and the North Sea. Ipswich is both on the Great Eastern Main Line r ...

and Marblehead.

Even though he did not travel to the colony, he continued to operate in London on its behalf. In 1629 he worked to recruit sympathetic Puritan ministers to emigrate. He sought permission from the king's Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

to freely export provisions to the colony, claiming the colonists were in dire straits due to a shortage of provisions and threats from Native Americans. He and Governor Winthrop exchanged letters; in one written in 1636 Cradock promised £50 toward the establishment of an institute of higher learning now known as Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

.

Actions by the Massachusetts Bay Colony rulers came into question at the Privy Council in 1633. Several opponents of the Puritans levelled charges that the colony's administrators sought independence from the crown and laws of England; Cradock and other company representatives were called before the council to answer these charges. They successfully defended the actions of the colonists, but the Puritans' opponents succeeded in having ships full of colonists detained from sailing in February 1633/4 until the colonial charter was presented to the council for inspection. Cradock was called upon to provide it; he informed the council that the charter was in the colony, and secured the release of the ships with a promise to have the charter delivered. The colonial council in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, not wanting to send the document for fear the charter would be revoked, temporized, claiming in their July 1634 meeting that the document could only be released by a vote of the colony's General Court. It was not scheduled to meet until September, at which time the matter would be taken up. The General Court refused to consider the issue, and began fortifying Boston Harbour, expecting a military confrontation over the issue. The 1634 launch of a ship intended to carry a force to the colony was unsuccessful, ending the military threat to the colony. The political threats continued, and the charter of the Plymouth Council of New England, issuer of the colony's land grant, was revoked. Furthermore, criminal charges, some of them clearly trumped up, were laid against Cradock and others associated with the Massachusetts Bay Company in 1635. Cradock was acquitted of most of these charges, but was convicted of usurpation of authority and deprived of his ability to act on behalf of the company.

Politics

In 1640 Cradock was an auditor of the

In 1640 Cradock was an auditor of the City of London Corporation

The City of London Corporation, officially and legally the Mayor and Commonalty and Citizens of the City of London, is the municipal governing body of the City of London, the historic centre of London and the location of much of the United King ...

.Beaven, p. 290 In April 1640, he was elected member of parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

in the Short Parliament

The Short Parliament was a Parliament of England that was summoned by King Charles I of England on the 20th of February 1640 and sat from 13th of April to the 5th of May 1640. It was so called because of its short life of only three weeks.

Aft ...

, and he was again elected to the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened for only three weeks during the spring of 1640 after an 11-year parliamentary absence. In Septem ...

in November 1640. He and other London MPs were politically allied to the Parliamentarian faction of Sir Henry Vane the Younger

Sir Henry Vane (baptised 26 March 161314 June 1662), often referred to as Harry Vane and Henry Vane the Younger to distinguish him from his father, Henry Vane the Elder, was an English politician, statesman, and colonial governor. He was brie ...

, and he supported the '' Root and Branch'' petition calling for radical reforms of the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

. In the opening session of the Long Parliament he denounced the king's plan of fortifying the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

, and declared that the city would not contribute its share of taxes until the garrison was removed. In early May 1641 Cradock brought word to the Parliament reports that the king was planning to send armed troops to seize the Tower of London; this news sparked the Protestation of 1641

The Protestation of 1641 was an attempt to avert the English Civil War. Parliament passed a bill on 3 May 1641 requiring those over the age of 18 to sign the Protestation, an oath of allegiance to King Charles I and the Church of England, as a way ...

, in which Cradock played a leading role. He continued to be active in the Parliament, serving on a committee for recusant

Recusancy (from la, recusare, translation=to refuse) was the state of those who remained loyal to the Catholic Church and refused to attend Church of England services after the English Reformation.

The 1558 Recusancy Acts passed in the reign ...

s, until his death, which was apparently quite sudden, on 27 May 1641.

Family

Damaris, Matthew Cradock's daughter by his first wife, married first Thomas Andrewes, citizen and Leatherseller of London (the son of SirThomas Andrewes

Sir Thomas Andrewes (died 1659) was a London financier who supported the parliamentary cause during the English Civil Wars, and sat as a commissioner at the High Court of Justice for the trial of Charles I. During the Third English Civil War, as L ...

, Lord Mayor of London in 1649 and in 1651–52). There were several children: Andrewes died in 1653. She then married Ralph Cudworth

Ralph Cudworth ( ; 1617 – 26 June 1688) was an English Anglican clergyman, Christian Hebraist, classicist, theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is tau ...

, a leading figure of the Cambridge Platonists

The Cambridge Platonists were an influential group of Platonist philosophers and Christian theologians at the University of Cambridge that existed during the 17th century. The leading figures were Ralph Cudworth and Henry More.

Group and its nam ...

and Master of Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 170 graduate students. The college was founded by William Byngham in 1437 as ...

, by whom she became mother of three further sons and a daughter, Damaris Cudworth, Lady Masham. Matthew Cradock's daughter Damaris Cudworth died at High Laver

High Laver is a village and civil parish in the Epping Forest district of the county of Essex, England. The parish is noted for its association with the philosopher John Locke.

History

High Laver is historically a rural agricultural parish, pred ...

, Essex, in 1695.

Rebeccah Cradock, Matthew's second wife, remarried first to Richard Glover, and lastly to Benjamin Whichcote, another senior figure of the Cambridge Platonists, Provost of King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, the college lies beside the River Cam and faces out onto King's Parade in the centre of the city ...

, a close colleague of Ralph Cudworth's. Both were closely associated with Mathew Cradock's nephew, Samuel Cradock

Samuel Cradock, B.D. (1621?–1706) was a nonconformist tutor, who was born about 1621. He was an elder brother of Zachary Cradock.

Education

Cradock entered Emmanuel College, Cambridge, as a pensioner (fee-paying student) from Rutland, and was ...

(a pupil of Whichcote's), whose brother Zachary

Zachary is a male given name, a variant of Zechariah – the name of several Biblical characters.

People

*Pope Zachary (679–752), Pope of the Catholic Church from 741 to 752

* Zachary of Vienne (died 106), bishop of Vienne (France), martyr a ...

was Provost of Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

. Cudworth, Whichcote and the brothers Cradock had all been students at Emmanuel College, Cambridge

Emmanuel College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1584 by Sir Walter Mildmay, Chancellor of the Exchequer to Elizabeth I. The site on which the college sits was once a priory for Dominican mon ...

.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Charter of Massachusetts Bay

a copy in the

Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library.

The project contains online electronic copies of documents dating back to the be ...

at Yale Law School

Yale Law School (Yale Law or YLS) is the law school of Yale University, a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. It was established in 1824 and has been ranked as the best law school in the United States by ''U ...

* Carl Seaburg and Alan SeaburgA Peculiar Plantation: 17th Century Medford

extract from ''Medford on the Mystic'', published by The Medford Historical Society, April 1980. {{DEFAULTSORT:Cradock, Matthew Year of birth missing 1641 deaths English businesspeople Levant Company Directors of the British East India Company West Indies merchants Colonial governors of Massachusetts Roundheads 17th-century English merchants Members of the Parliament of England for the City of London English MPs 1640 (April) English MPs 1640–1648