Massacre Of The Acqui Division on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The massacre of the Acqui Division, also known as the Cephalonia massacre, was the mass execution of the soldiers of the Italian

/ref> On 8 September 1943, the day the armistice was made public, General

("common cause", Ambrosio's tactics and Badoglio's paradox on page 423)

(Corfu info and poll on bottom of page 424) (no match reference, Hitler's orders

"delirium of omnipotence" and Austrian origin

on page 425)Refusal to bury dead

on page 427)

In the case of a German attack, Vecchiarelli's order was not very specific because it was based on General  Gandin finally agreed to withdraw his soldiers from their strategic location on Mount Kardakata, the island's "nerve centre", in return for a German promise not to bring reinforcements from the Greek mainland and on 12 September, he informed Barge that he was prepared to surrender the Acqui's weapons, as Lt Colonel Barge reported to his superiors in the XXII Mountain Corps. However, Gandin was under pressure not to come to an agreement with the Germans from his junior officers who were threatening mutiny. The Acqui's detached regiment on

Gandin finally agreed to withdraw his soldiers from their strategic location on Mount Kardakata, the island's "nerve centre", in return for a German promise not to bring reinforcements from the Greek mainland and on 12 September, he informed Barge that he was prepared to surrender the Acqui's weapons, as Lt Colonel Barge reported to his superiors in the XXII Mountain Corps. However, Gandin was under pressure not to come to an agreement with the Germans from his junior officers who were threatening mutiny. The Acqui's detached regiment on

hfmeyer.com; accessed 6 December 2014. At the same time, the Germans started dropping

/ref> The ''Gebirgsjäger'' soldiers began executing their Italian prisoners in groups of four to ten. The Germans first killed the surrendering Italians, where they stood, using machine-guns. After this stage was over, the Germans marched the remaining soldiers to the San Teodoro town hall and had the prisoners executed by eight member detachments. General Gandin and 137 of his senior officers were summarily court-martialled on 24 September and executed, their bodies discarded at sea. The divisional infantry commander, General Luigi Gherzi, had already been executed on 22 September, immediately after his capture, while the fighting was still ongoing. Romualdo Formato, one of ''Acquis seven

BBC.co.uk, 26 March 2001; accessed 6 December 2014. The bodies of the ca. 5,000 men who were executed were disposed of in a variety of ways. Bodies were cremated in massive wood

Google translation

Others, according to Amos Pampaloni, one of the survivors, were executed in full sight of the Greek population in Argostoli harbour on 23 September 1943 and their bodies were left to rot where they fell, while in smaller streets corpses were decomposing and the stench was insufferable to the point that he could not remain there long enough to take a picture of the carnage. The Guardian UK Quote: "In an entry dated 23 September 1943, Corporal Richter registers the execution of Italian soldiers in Argostoli harbour, in full sight of Greek civilians and with the bodies left to rot in the autumn heat. 'In one of the small streets the smell is so bad that I can't even take a picture', he reports." Bodies were thrown into the sea, with rocks tied around them. In addition, the Germans had refused to allow the Acqui soldiers to bury their dead. A chaplain set out to find bodies, discovering bones scattered all over. The few soldiers who were saved were assisted by locals and the

The events in Cephalonia were repeated, to a lesser extent, elsewhere. In

The events in Cephalonia were repeated, to a lesser extent, elsewhere. In

Major Harald von Hirschfeld was never tried for his role in the massacre since he did not survive the war: in December 1944, he became the Wehrmacht's youngest

Major Harald von Hirschfeld was never tried for his role in the massacre since he did not survive the war: in December 1944, he became the Wehrmacht's youngest

In the 1950s, the remains of about 3,000 soldiers, including 189 officers, were exhumed and transported back to Italy for burial in the Italian War Cemetery in

In the 1950s, the remains of about 3,000 soldiers, including 189 officers, were exhumed and transported back to Italy for burial in the Italian War Cemetery in Monument to the Acqui Division

, kefalonianet.gr; accessed 6 December 2014.

War crimes forum

L'eccidio della Divisione Acqui

{{DEFAULTSORT:Acqui Division 1943 in Greece Conflicts in 1943 Massacres in 1943 Nazi war crimes in Greece Mass graves World War II prisoner of war massacres by Nazi Germany Italian resistance movement Greek Resistance Military history of Italy during World War II Military history of Germany during World War II Italian occupation of Greece during World War II German occupation of Greece during World War II Massacres in Greece during World War II History of Cephalonia September 1943 events War crimes of the Wehrmacht

33rd Infantry Division "Acqui"

The 33rd Infantry Division "Acqui" ( it, 33ª Divisione di fanteria "Acqui") was an infantry division of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. The Acqui was classified as a mountain infantry division, which meant that its artillery was mov ...

by German soldiers on the island of Cephalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia ( el, Κεφαλονιά), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallenia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It i ...

, Greece, in September 1943, following the Italian armistice

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Brigad ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. About 5,000 soldiers were executed, and around 3,000 more drowned.

Following the decision of the Italian government to negotiate a surrender to the Allies in 1943, the German Army tried to disarm the Italians during Operation Achse

Operation Achse (german: Fall Achse, lit=Case Axis), originally called Operation Alaric (), was the codename for the German operation to forcibly disarm the Italian armed forces after Italy's armistice with the Allies on 3 September 1943.

S ...

. On 13 September the Italians of the Acqui resisted, and fought the Germans on the island of Cephalonia. By 22 September the last of the Italian resistance surrendered after running out of ammunition. A total of 1,315 Italians were killed in the battle, 5,155 were executed by 26 September, and 3,000 drowned when the German ships taking the survivors to concentration camps were sunk by the Allies. It was one of the largest prisoner of war massacres of the war, along with the Katyn massacre

The Katyn massacre, "Katyń crime"; russian: link=yes, Катынская резня ''Katynskaya reznya'', "Katyn massacre", or russian: link=no, Катынский расстрел, ''Katynsky rasstrel'', "Katyn execution" was a series of m ...

, and it was one of many atrocities committed by the 1st Mountain Division (german: 1. Gebirgs Division).

History

Background

Since the fall of Greece in April–May 1941, the country had been divided inoccupation zones

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and France ...

, with the Italians getting the bulk of the mainland and most islands. The ''Acqui'' Division had been the Italian garrison of Cephalonia since May 1943, and consisted of 11,500 soldiers and 525 officers. It was composed of two infantry regiments (the 17th and the 317th), the 33rd artillery regiment, the 27th Blackshirt Legion with the XIX Blackshirt Battalion and support units. Furthermore, its 18th Regiment was detached to garrison duties in Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

. The Acqui also had naval coastal batteries, torpedo boats and two aircraft. From 18 June 1943, it was commanded by the 52-year-old General Antonio Gandin

Antonio Gandin (13 May 1891 – 24 September 1943) was an Italian general, who was killed in Kefalonia in September 1943 during the Massacre of the Acqui Division.

Biography

Antonio Gandin was born in Avezzano in 1891, son of Pietro, prefect ...

, a decorated veteran of the Russian Front where he earned the German Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia est ...

.

The Germans decided to reinforce their presence throughout the Balkans, following Allied successes and the possibility that Italy might seek accommodation with the Allies. On 5–6 July Lt Colonel Johannes Barge arrived with 2,000 men of the 966th Fortress Grenadier Regiment, including Fortress-Battalions 810 and 909 and a battery of self-propelled guns and nine tanks.

After Italy's armistice with the Allies in September 1943, General Gandin found himself in a dilemma: one option was surrendering to the Germans – who were already prepared for the eventuality and had begun disarming Italian garrisons elsewhere – or trying to resist. Initially, Gandin requested instructions from his superiors and began negotiations with Barge.Translation by Google/ref> On 8 September 1943, the day the armistice was made public, General

Carlo Vecchiarelli

Carlo Vecchiarelli (10 January 1884 – 13 December 1948) was an Italian general. He was a veteran combatant of the First World War. Between the two world wars he held the positions of Military Attaché at the Italian Embassy in Prague, Honora ...

, commander of the 170,000-strong Italian army occupying Greece, telegram

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

med Gandin his order, essentially a copy of General Ambrosio's ''promemoria 2'' from Headquarters. Vecchiarelli's order instructed that if the Germans did not attack the Italians, the Italians should not attack the Germans. Ambrosio's order stated that the Italians should not "make common cause" with the Greek partisans or even the Allies, should they arrive in Cephalonia. Comments:("common cause", Ambrosio's tactics and Badoglio's paradox on page 423)

(Corfu info and poll on bottom of page 424) (no match reference, Hitler's orders

"delirium of omnipotence" and Austrian origin

on page 425)

on page 427)

Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

's directive which stated that the Italians should respond with "maximum decision" to any threat from any side. The order implied that the Italians should defend themselves but did not explicitly state so. At 22:30 hours of the same day Gandin received an order directly from General Ambrosio to send most of his naval and merchant vessels to Brindisi immediately, as demanded by the terms of the armistice. Gandin complied, thus losing a possible means of escape.

To make matters even more complicated Badoglio had agreed, after the overthrow of Mussolini, to the unification of the two armies under German command, in order to appease the Germans. Therefore, technically, both Vecchiarelli and Gandin were under German command, even though Italy had implemented an armistice agreement with the Allies. That gave the Germans a sense of justification in treating any Italians disobeying their orders as mutineers or ''francs-tireur

(, French for "free shooters") were irregular military formations deployed by France during the early stages of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). The term was revived and used by partisans to name two major French Resistance movements se ...

s'', which, at that time, the laws of war

The law of war is the component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of warring parties (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territor ...

considered unlawful combatant

An unlawful combatant, illegal combatant or unprivileged combatant/belligerent is a person who directly engages in armed conflict in violation of the laws of war and therefore is claimed not to be protected by the Geneva Conventions.

The Internati ...

s subject to execution on capture.

At 9:00 hours on 9 September, Barge met with Gandin and misled him by stating that he had received no orders from the German command. The two men liked each other and they had things in common as Gandin was pro-German and liked Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as treat ...

. Indeed, Gandin's pro-German attitude was the reason he had been sent by General Ambrosio to command the ''Acqui'' Division: fearing he might side with the Germans against the evolving plot to depose Mussolini, Ambrosio wanted Gandin out of Italy. Both men ended their meeting on good terms, agreeing to wait for orders and also that the situation should be resolved peacefully.

On 11 September, the Italian High Command sent two explicit instructions to Gandin, to the effect that "German troops have to be viewed as hostile" and that "disarmament attempts by German forces must be resisted with weapons". That same day Barge handed Gandin an ultimatum, demanding a decision given the following three options:

#Continue fighting on the German side #Fight against the Germans #Hand over arms peacefullyGandin brought Barge's ultimatum to his senior officers and the seven chaplains of the Acqui for discussion. Six of the chaplains and all of his senior officers advised him to comply with the German demands while one of the chaplains suggested immediate surrender. However, Gandin could not agree to join the Germans because that would be against the King's orders as relayed by

Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino (, ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regime ...

. He also did not want to fight them because, as he said, "they had fought with us and for us, side by side". On the other hand, surrendering the weapons would violate the spirit of the armistice. Despite the orders from the Italian GHQ, Gandin chose to continue negotiating with Barge.

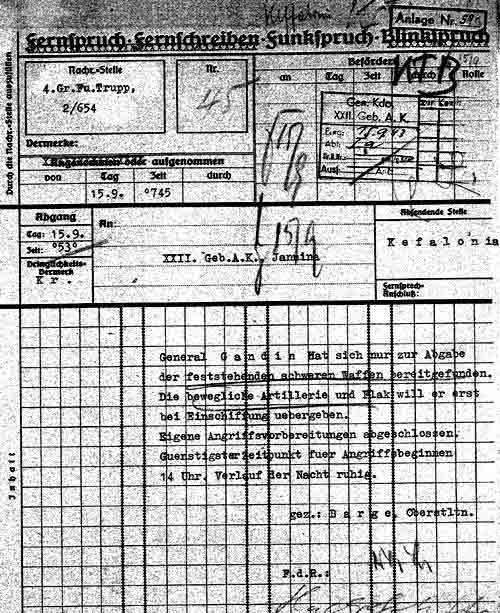

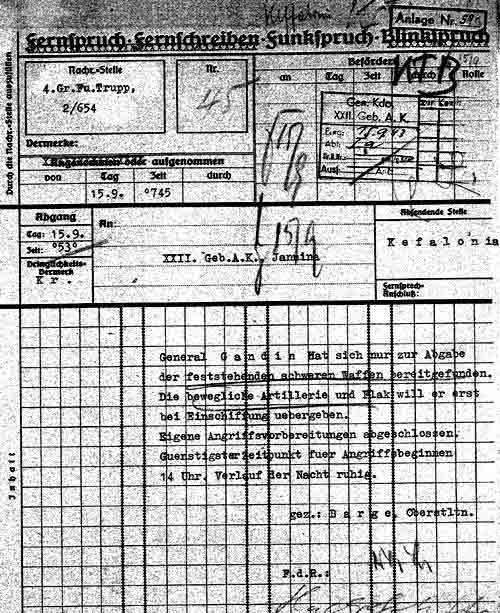

Gandin finally agreed to withdraw his soldiers from their strategic location on Mount Kardakata, the island's "nerve centre", in return for a German promise not to bring reinforcements from the Greek mainland and on 12 September, he informed Barge that he was prepared to surrender the Acqui's weapons, as Lt Colonel Barge reported to his superiors in the XXII Mountain Corps. However, Gandin was under pressure not to come to an agreement with the Germans from his junior officers who were threatening mutiny. The Acqui's detached regiment on

Gandin finally agreed to withdraw his soldiers from their strategic location on Mount Kardakata, the island's "nerve centre", in return for a German promise not to bring reinforcements from the Greek mainland and on 12 September, he informed Barge that he was prepared to surrender the Acqui's weapons, as Lt Colonel Barge reported to his superiors in the XXII Mountain Corps. However, Gandin was under pressure not to come to an agreement with the Germans from his junior officers who were threatening mutiny. The Acqui's detached regiment on Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

, not commanded by Gandin, also informed him at around midnight 12–13 September, by radio communication

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmit ...

, that they had rejected an agreement with the Germans. Gandin also heard from credible sources that soldiers who had surrendered were being deported and not repatriated.

On 13 September, a German convoy of five ships approached the island's capital, Argostoli

Argostoli ( el, Αργοστόλι, Katharevousa: Ἀργοστόλιον) is a town and a municipality on the island of Kefalonia, Ionian Islands, Greece. Since the 2019 local government reform it is one of the three municipalities on the island ...

. Italian artillery officers, on their own initiative, ordered the remaining batteries to open fire, sinking two German landing craft

Landing craft are small and medium seagoing watercraft, such as boats and barges, used to convey a landing force (infantry and vehicles) from the sea to the shore during an amphibious assault. The term excludes landing ships, which are larger. Pr ...

and killing five Germans.

Under these circumstances, that same night, Gandin presented his troops with a poll

Poll, polled, or polling may refer to:

Figurative head counts

* Poll, a formal election

** Election verification exit poll, a survey taken to verify election counts

** Polling, voting to make decisions or determine opinions

** Polling places o ...

, essentially containing the three options presented to him by Barge:

#Join the Germans #Surrender and be repatriated #Resist the German forcesThe response from the Italian troops was in favour of the third option by a large majority but there is no available information as to the exact size of the majority, and therefore on 14 September Gandin reneged on the agreement, refusing to surrender anything but the division's heavy artillery and telling the Germans to leave the island, demanding a reply by 9:00 the next day.

Battle with the Germans

As the negotiations stalled, the Germans prepared to resolve the crisis by force and presented the Italians with an ultimatum which expired at 14:00 hours on 15 September. On the morning of 15 September, the German Luftwaffe began bombarding the Italian positions withStuka

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Cond ...

dive-bombers. On the ground, the Italians initially enjoyed superiority, and took about 400 Germans prisoner. On 17 September however, the Germans landed the "Battle Group Hirschfeld", composed of the III./98 and the 54th Mountain Battalions of the German Army's elite 1st Mountain Division, together with I./724 Battalion of the 104th Jäger Division

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1. I ...

, under the command of Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

Harald von Hirschfeld. The 98th ''Gebirgsjäger'' Regiment, in particular, had been involved in several atrocities against civilians in Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich ...

in the months preceding the Acqui massacre.Meyer, Hermann Frank: Die 1. Gebirgs-Division in Epirus im Sommer 1943hfmeyer.com; accessed 6 December 2014. At the same time, the Germans started dropping

propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

leaflets calling upon the Italians to surrender. The leaflets stated: "Italian comrades, soldiers and officers, why fight against the Germans? You have been betrayed by your leaders!... LAY DOWN YOUR ARMS!! THE ROAD BACK TO YOUR HOMELAND WILL BE OPENED UP FOR YOU BY YOUR GERMAN COMRADES".Gandin repeatedly requested help from the Ministry of War in Brindisi, but he did not get any reply. He even went so far as sending a

Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million Volunteering, volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure re ...

emissary to the Ministry, but the mission broke down off the coast of Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

and when it arrived three days later at the Italian High Command in Brindisi, it was already too late. In addition, 300 planes loyal to Badoglio were located at Lecce

Lecce ( ); el, label=Griko, Luppìu, script=Latn; la, Lupiae; grc, Λουπίαι, translit=Loupíai), group=pron is a historic city of 95,766 inhabitants (2015) in southern Italy. It is the capital of the province of Lecce, the province ...

, near the southernmost point of Italy, well within range of Cephalonia, and were ready to intervene. But the Allies would not let them go because they feared they could have defected to the German side. Furthermore, two Italian torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s, already on their way to Cephalonia, were ordered back to port by the Allies for the same reasons.

Despite help for the Italians from the local population, including the island's small ELAS

The Greek People's Liberation Army ( el, Ελληνικός Λαϊκός Απελευθερωτικός Στρατός (ΕΛΑΣ), ''Ellinikós Laïkós Apeleftherotikós Stratós'' (ELAS) was the military arm of the left-wing National Liberat ...

partisan detachments, the Germans enjoyed complete air superiority and their troops had extensive combat experience, in contrast with the conscripts of Acqui, who were no match for the Germans. In addition, Gandin had withdrawn the Acqui from the elevated position on Mount Kardakata and that gave the Germans an additional strategic advantage. After several days of fighting, at 11:00 hours on 22 September, following Gandin's orders, the last Italians surrendered, having run out of ammunition and having lost 1,315 men. According to German sources, the losses were 300 Germans and 1,200 Italians. 15 Greek partisans were also killed fighting alongside the ''Acqui''.

Massacre

The massacre started on 21 September, and lasted for one week. After the Italian surrender,Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

had issued an order allowing the Germans to summarily execute any Italian officer who resisted "for treason", and on 18 September, the German High Command issued an order stating that "because of the perfidious and treacherous behaviour f the Italianson Cephalonia, no prisoners are to be taken."Google translation/ref> The ''Gebirgsjäger'' soldiers began executing their Italian prisoners in groups of four to ten. The Germans first killed the surrendering Italians, where they stood, using machine-guns. After this stage was over, the Germans marched the remaining soldiers to the San Teodoro town hall and had the prisoners executed by eight member detachments. General Gandin and 137 of his senior officers were summarily court-martialled on 24 September and executed, their bodies discarded at sea. The divisional infantry commander, General Luigi Gherzi, had already been executed on 22 September, immediately after his capture, while the fighting was still ongoing. Romualdo Formato, one of ''Acquis seven

chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a hosp ...

s and one of the few survivors, wrote that during the massacre, the Italian officers started to cry, pray and sing. Many were shouting the names of their mothers, wives and children. According to Formato's account, three officers hugged and stated that they were comrades while alive and now in death they would go together to paradise, while others were digging through the grass as if trying to escape. In one place, Formato recalled, "the Germans went around loudly offering medical help to those wounded. When about 20 men crawled forward, a machine-gun salvo finished them off." Officers gave Formato their belongings to take with him and give to their families back in Italy. The Germans, however, confiscated the items and Formato could no longer account for the exact number of the officers killed.

The executions of the Italian officers were continuing when a German officer came and reprieved Italians who could prove they were from South Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous province

, image_skyline =

, image_alt ...

as that region had been annexed by Hitler as German province after 8 September. Seeing an opportunity, Formato begged the officer to stop the killings and save the few officers remaining. The German officer responded and told Formato that he would consult with his commanding officer. When the officer returned, after half an hour, he informed Formato that the killings of the officers would stop. The number of Italian surviving officers, including Formato, totaled 37. After the reprieve the Germans congratulated the remaining Italians and offered them cigarettes. The situation remained unstable, however. Following the reprieve, the Germans forced twenty Italian sailors to load the bodies of the dead officers on rafts and take them out to sea. The Germans then blew up the rafts with the Italian sailors on board.

Alfred Richter, an Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

and one of the participants in the massacre, recounted how a soldier who sang aria

In music, an aria (Italian: ; plural: ''arie'' , or ''arias'' in common usage, diminutive form arietta , plural ariette, or in English simply air) is a self-contained piece for one voice, with or without instrumental or orchestral accompanime ...

s for the Germans in the local taverns was forced to sing while his comrades were being executed. The singing soldier's fate remains unknown. Richter stated that he and his regiment comrades felt "a delirium of omnipotence" during the events. Most of the soldiers of the German regiment were Austrians.

According to Richter the Italian soldiers were killed after surrendering to the soldiers of the 98th Regiment. He described that the bodies were then thrown into heaps, all shot in the head. Soldiers of the 98th Regiment started removing the boots from the corpses for their own use. Richter mentioned that groups of Italians were taken into quarries and walled gardens near the village of Frangata and executed by machine gun fire. The killing lasted for two hours, during which time the sound of the shooting and the screams of the victims could be heard inside the homes of the village."Nazi massacre on island idyll"BBC.co.uk, 26 March 2001; accessed 6 December 2014. The bodies of the ca. 5,000 men who were executed were disposed of in a variety of ways. Bodies were cremated in massive wood

pyre

A pyre ( grc, πυρά; ''pyrá'', from , ''pyr'', "fire"), also known as a funeral pyre, is a structure, usually made of wood, for burning a body as part of a funeral rite or execution. As a form of cremation, a body is placed upon or under the ...

s, which made the air of the island thick with the smell of burning flesh, or moved to ships where they were buried at sea. (Mentions the fireGoogle translation

Others, according to Amos Pampaloni, one of the survivors, were executed in full sight of the Greek population in Argostoli harbour on 23 September 1943 and their bodies were left to rot where they fell, while in smaller streets corpses were decomposing and the stench was insufferable to the point that he could not remain there long enough to take a picture of the carnage. The Guardian UK Quote: "In an entry dated 23 September 1943, Corporal Richter registers the execution of Italian soldiers in Argostoli harbour, in full sight of Greek civilians and with the bodies left to rot in the autumn heat. 'In one of the small streets the smell is so bad that I can't even take a picture', he reports." Bodies were thrown into the sea, with rocks tied around them. In addition, the Germans had refused to allow the Acqui soldiers to bury their dead. A chaplain set out to find bodies, discovering bones scattered all over. The few soldiers who were saved were assisted by locals and the

ELAS

The Greek People's Liberation Army ( el, Ελληνικός Λαϊκός Απελευθερωτικός Στρατός (ΕΛΑΣ), ''Ellinikós Laïkós Apeleftherotikós Stratós'' (ELAS) was the military arm of the left-wing National Liberat ...

organisation. One of the survivors was taken heavily wounded to a Cephalonian lady's home by a taxi driver and survived the war to live in Lake Como

Lake Como ( it, Lago di Como , ; lmo, label=Western Lombard, Lagh de Còmm , ''Cómm'' or ''Cùmm'' ), also known as Lario (; after the la, Larius Lacus), is a lake of glacial origin in Lombardy, Italy. It has an area of , making it the thir ...

. An additional three thousand of the survivors in German custody drowned, when the ships ''Sinfra

Sinfra is a city in central Ivory Coast. It is a sub-prefecture and the seat of Sinfra Department in Marahoué Region, Sassandra-Marahoué District. Sinfra is also a commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune o ...

'', '' Mario Roselli'' and ''Ardena'', transporting them to concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

, were sunk by Allied air raids and sea mines in the Adriatic. These losses and similar ones from the Italian Dodecanese garrisons were also the result of German policy, as Hitler had instructed the local German commanders to forgo "all safety precautions" during the transport of prisoners, "regardless of losses". In a book review published by ''Corriere della Sera

The ''Corriere della Sera'' (; en, "Evening Courier") is an Italian daily newspaper published in Milan with an average daily circulation of 410,242 copies in December 2015.

First published on 5 March 1876, ''Corriere della Sera'' is one of It ...

'', other estimates of the Italian soldiers massacred at Cephalonia range between 1,650–3,800.

Aftermath

The events in Cephalonia were repeated, to a lesser extent, elsewhere. In

The events in Cephalonia were repeated, to a lesser extent, elsewhere. In Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

, the 8,000-strong Italian garrison comprised elements of three divisions, including the ''Acqui's'' 18th Regiment. On 24 September, the Germans landed a force on the island (characteristically codenamed "Operation Treason"), and by the next day they were able to induce the Italians to capitulate.

All 280 Italian officers on the island were executed during the next two days on the orders of General Lanz, in accordance with Hitler's directives. The bodies were loaded onto a ship and disposed of in the sea. Similar executions of officers also occurred in the aftermath of the Battle of Kos

The Battle of Kos ( el, Μάχη της Κω) was a brief battle in World War II between United Kingdom, British/Kingdom of Italy, Italian and Nazi Germany, German forces for control of the Greece, Greek island of Kos, in the then Italian-held ...

, where between 96 and 103 Italian officers were shot along with their commander.

In October 1943, after Mussolini had been freed and established his new Fascist Republic in Northern Italy

Northern Italy ( it, Italia settentrionale, it, Nord Italia, label=none, it, Alta Italia, label=none or just it, Nord, label=none) is a geographical and cultural region in the northern part of Italy. It consists of eight administrative regions ...

, the Germans gave the remaining Italian prisoners three choices:

#Continue fighting on the German side #Most Italians opted for the second choice. In January 1944, a chaplain's account reachedForced labour Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...on the island #Concentration camps in Germany

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

after Aurelio Garobbio, a Swiss Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

from the Italian-speaking Canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ent ...

of Ticino

Ticino (), sometimes Tessin (), officially the Republic and Canton of Ticino or less formally the Canton of Ticino,, informally ''Canton Ticino'' ; lmo, Canton Tesin ; german: Kanton Tessin ; french: Canton du Tessin ; rm, Chantun dal Tessin . ...

, informed him about the events. Mussolini became incensed that the Germans would do such a thing, although he considered the ''Acqui'' division's officers, more so than its soldiers, as traitors. Nevertheless, in one of his exchanges with Garobbio, after Garobbio complained that the Germans showed no mercy, he said: "But our men defended themselves, you know. They hit several German landing craft sinking them. They fought how Italians know how to fight".

Prosecution

Major Harald von Hirschfeld was never tried for his role in the massacre since he did not survive the war: in December 1944, he became the Wehrmacht's youngest

Major Harald von Hirschfeld was never tried for his role in the massacre since he did not survive the war: in December 1944, he became the Wehrmacht's youngest general officer

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

, and was killed while fighting

Combat ( French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict meant to physically harm or kill the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is sometimes resorted to as a method of self-defense, or ...

at the Dukla Pass

The Dukla Pass ( sk, Dukliansky priesmyk, pl, Przełęcz Dukielska, hu, Duklai-hágó, cz, Dukelský průsmyk; 502 m AMSL) is a strategically significant mountain pass in the Laborec Highlands of the Outer Eastern Carpathians, on the border b ...

in Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

in 1945. Only Hirschfeld's superior commander, General Hubert Lanz

Karl Hubert Lanz (22 May 1896 – 15 August 1982) was a German general during the Second World War, in which he led units in the Eastern Front and in the Balkans. After the war, he was tried for war crimes and convicted in the Southeast Case, sp ...

, was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment at the so-called "Southeast Case

The Hostages Trial (or, officially, ''The United States of America v. Wilhelm List, et al.'') was held from

8 July 1947 until 19 February 1948 and was the seventh of the twelve trials for war crimes that United States authorities held in their oc ...

" of the Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

for the Cephalonia massacre, as well as the participation of his men in other atrocities in Greece like the massacre of Kommeno

The Massacre of Kommeno ( el, Η σφαγή του Κομμένου; german: Massaker von Kommeno) was a Nazi war crime perpetrated by members of the Wehrmacht in the village of Kommeno, Greece, in 1943, during the German occupation of Greece in ...

on 16 August 1943. He was released in 1951 and died in 1982. Lt Colonel Barge was not on the island when the massacre was taking place. He was subsequently decorated with the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

The Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross (german: Ritterkreuz des Eisernen Kreuzes), or simply the Knight's Cross (), and its variants, were the highest awards in the military and paramilitary forces of Nazi Germany during World War II.

The Knight' ...

for his service in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

. He died in 2000.

The reason for Lanz's light sentence was that the court at Nuremberg was deceived by false evidence and did not believe that the massacre took place, despite a book about the massacre by ''padre'' Formato published in 1946, a year before the trial. Because there was doubt as to who issued what order, Lanz was only charged with the deaths of Gandin and the officers. Lanz lied in court by stating he had refused to obey Hitler's orders to shoot the prisoners because he was revolted by them. He claimed that the report to Army Group E, claiming 5,000 soldiers were shot, was a ruse employed to deceive the army command in order to hide the fact that he had disobeyed the Führer's orders. He added that fewer than a dozen officers were shot and the rest of the Acqui Division was transported to Piraeus

Piraeus ( ; el, Πειραιάς ; grc, Πειραιεύς ) is a port city within the Athens urban area ("Greater Athens"), in the Attica region of Greece. It is located southwest of Athens' city centre, along the east coast of the Saronic ...

through Patras

)

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 =

, demographics1_info2 =

, timezone1 = EET

, utc_offset1 = +2

, ...

.

In his testimony, Lanz was assisted by affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a statemen ...

s from other Germans such as General von Butlar from Hitler's personal staff, who was involved in the Ardeatine massacre

The Ardeatine massacre, or Fosse Ardeatine massacre ( it, Eccidio delle Fosse Ardeatine), was a mass killing of 335 civilians and political prisoners carried out in Rome on 24 March 1944 by German occupation troops during the Second World War ...

. The Germans were with Lanz in September 1943 and swore that the massacre had never taken place. In addition, for reasons unknown, the Italian side never presented any evidence for the massacre at the Nuremberg trials. It is speculated that the Italians, reeling from armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

terms highly unfavourable for their country, refused to cooperate with the trial process. Given the circumstances the court accepted Lanz's position that he prevented the massacre and that the event never happened. Consequently, Lanz received a lighter sentence than General Rendulic for his misdeed in Yugoslavia, who was released in late 1951 nevertheless, after only three years of imprisonment.

Lanz's defence emphasised that the prosecution had not presented any Italian evidence for the massacre and claimed that there was no evidence the Italian headquarters in Brindisi

Brindisi ( , ) ; la, Brundisium; grc, Βρεντέσιον, translit=Brentésion; cms, Brunda), group=pron is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea.

Histo ...

had ever instructed Gandin and his Division to fight. Therefore, according to the logic of the defence, Gandin and his men were either mutineers

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military, of a crew or of a crew of pirates) to oppose, change, or overthrow an organization to which they were previously loyal. The term is commonly used for a rebellion among memb ...

or ''franc-tireur

(, French for "free shooters") were irregular military formations deployed by France during the early stages of the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71). The term was revived and used by partisans to name two major French Resistance movements se ...

s'' and did not qualify for POW status under the Geneva conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

.

The Germans justified their behaviour by claiming the Italians were negotiating the surrender of the island to the British. The German claim was not entirely unfounded: in the Greek mainland, an entire division went over to the Greek guerrillas, and in the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

, the Italians had joined forces with the British, resulting in a two-month German campaign

The German campaign (german: Befreiungskriege , lit=Wars of Liberation ) was fought in 1813. Members of the Sixth Coalition, including the German states of Austria and Prussia, plus Russia and Sweden, fought a series of battles in Germany ag ...

to evict them.

An attempt to revisit the case by the Dortmund

Dortmund (; Westphalian nds, Düörpm ; la, Tremonia) is the third-largest city in North Rhine-Westphalia after Cologne and Düsseldorf, and the eighth-largest city of Germany, with a population of 588,250 inhabitants as of 2021. It is the la ...

state prosecutor Johannes Obluda in 1964 came to naught, as the political climate in Germany at the time was in favour of "putting the war behind". In 2002 Dortmund prosecutor Ultrich Maaßs reopened a case against certain persons responsible for the massacre. In his office, along with a map of the world, Maaßs displayed a map of Cephalonia with the dates and locations of the executions as well as the names of the victims. No indictments or arrests resulted from Maaßs' investigation. Ten ex-members of the 1st Gebirgs Division have been investigated, out of 300 still alive.

In 2013, Alfred Stork, a 90-year-old German ex-corporal, was sentenced to life imprisonment for his role in the massacre by a military court in Rome.

Commemoration

In the 1950s, the remains of about 3,000 soldiers, including 189 officers, were exhumed and transported back to Italy for burial in the Italian War Cemetery in

In the 1950s, the remains of about 3,000 soldiers, including 189 officers, were exhumed and transported back to Italy for burial in the Italian War Cemetery in Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Italy a ...

. The remains of General Gandin were never identified.

The subject of the massacre was largely ignored in Italy by the press and the educational system until 1980, when the Italian President Sandro Pertini

Alessandro "Sandro" Pertini (; 25 September 1896 – 24 February 1990) was an Italian socialist politician who served as the president of Italy from 1978 to 1985.

Early life

Born in Stella (Province of Savona) as the son of a wealthy landown ...

, a former partisan

Partisan may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (weapon), a pole weapon

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

Films

* ''Partisan'' (film), a 2015 Australian film

* ''Hell River'', a 1974 Yugoslavian film also know ...

, unveiled the memorial in Cephalonia. The massacre provided the historical background to the 1994 novel ''Captain Corelli's Mandolin

''Captain Corelli's Mandolin'', released simultaneously in the United States as ''Corelli's Mandolin'', is a 1994 novel by the British writer Louis de Bernières, set on the Greek island of Cephalonia during the Italian and German occupatio ...

''. Despite the recognition of the event by Pertini, it was not until March 2001 that another Italian President, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (; 9 December 1920 – 16 September 2016) was an Italian politician and banker who was the prime minister of Italy from 1993 to 1994 and the president of Italy from 1999 to 2006.

Biography Education

Ciampi was born i ...

, visited the memorial again, and even then he was most likely influenced by the publicity generated by the impending release of the Hollywood film ''Captain Corelli's Mandolin

''Captain Corelli's Mandolin'', released simultaneously in the United States as ''Corelli's Mandolin'', is a 1994 novel by the British writer Louis de Bernières, set on the Greek island of Cephalonia during the Italian and German occupatio ...

'', based on the novel with the same name. Thanks to these actions today a large number of streets in Italy are named after "Divisione Acqui".

During the ceremony Ciampi, referring to the men of the Acqui Division, declared that their "conscious decision was the first act of resistance by an Italy freed from fascism" and that "they preferred to fight and die for their fatherland". The massacre of the ''Acqui'' Division is emerging as a subject of ongoing research, and is regarded as a leading example of the Italian Resistance during World War II.

In 2002 the Italian post issued the commemorative stamp ''Eccidio della Divisione Aqui''.

The Presidents of Greece and Italy periodically commemorate the event during ceremonies taking place in Cephalonia at the monument of the ''Acqui'' Division. An academic conference about the massacre was held on 2–3 March 2007 in Parma

Parma (; egl, Pärma, ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmigiano-Reggiano, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,292 ...

, Italy.

Cephalonia's Greco-Italian Society maintains an exhibition called "The Mediterraneo Exhibition", next to the Catholic church in Argostoli

Argostoli ( el, Αργοστόλι, Katharevousa: Ἀργοστόλιον) is a town and a municipality on the island of Kefalonia, Ionian Islands, Greece. Since the 2019 local government reform it is one of the three municipalities on the island ...

, where pictures, newspaper articles and documents showcasing the story of the massacre are displayed.Gill, John and Edwards, Nick. , kefalonianet.gr; accessed 6 December 2014.

See also

*Massacre of Kos

The Massacre of Kos ( it, Eccidio di Kos) was a war crime perpetrated in early October 1943 by the Wehrmacht against Italian army POWs on the Dodecanese island of Kos, then under Italian occupation. About a hundred Italian officers were shot on ...

*List of massacres in Greece

Ancient Greece

Roman Empire / Byzantine Empire

Ottoman Greece

Greek War of Independence (1821–1832)

First Balkan War

Second Balkan War

World War II

References

{{Europe topic , List of massacres in

Lists of massacres by ...

*War crimes of the Wehrmacht

During World War II, the German combined armed forces ( ''Heer'', ''Kriegsmarine'' and ''Luftwaffe'') committed systematic war crimes, including massacres, mass rape, looting, the exploitation of forced labor, the murder of three million Sov ...

References

External links

War crimes forum

L'eccidio della Divisione Acqui

{{DEFAULTSORT:Acqui Division 1943 in Greece Conflicts in 1943 Massacres in 1943 Nazi war crimes in Greece Mass graves World War II prisoner of war massacres by Nazi Germany Italian resistance movement Greek Resistance Military history of Italy during World War II Military history of Germany during World War II Italian occupation of Greece during World War II German occupation of Greece during World War II Massacres in Greece during World War II History of Cephalonia September 1943 events War crimes of the Wehrmacht