Martino Zaccaria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Martino Zaccaria was the Lord of Chios from 1314 to 1329, ruler of several other Aegean islands, and baron of Veligosti–Damala and

If these ties to the Latin Emperor provoked displeasure at the Byzantine court, for the time being relations remained good: the lease of Chios was renewed in 1324, and in 1327 Martino took part in alliance negotiations between the Byzantines and the

If these ties to the Latin Emperor provoked displeasure at the Byzantine court, for the time being relations remained good: the lease of Chios was renewed in 1324, and in 1327 Martino took part in alliance negotiations between the Byzantines and the

Martino Zaccaria married, probably some time before 1325, Jacqueline de la Roche. An earlier conjecture of

Martino Zaccaria married, probably some time before 1325, Jacqueline de la Roche. An earlier conjecture of

Chalandritsa

Chalandritsa ( el, Χαλανδρίτσα) is a town and a community in Achaea, West Greece, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Erymanthos, of which it is the seat of administration.

Chalandritsa is si ...

in the Principality of Achaea

The Principality of Achaea () or Principality of Morea was one of the three vassal states of the Latin Empire, which replaced the Byzantine Empire after the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade. It became a vassal of the Kingdom ...

. He distinguished himself in the fight against Turkish corsairs in the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

, and received the title of "King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

and Despot of Asia Minor" from the titular Latin Emperor

The Latin Emperor was the ruler of the Latin Empire, the historiographical convention for the Crusader realm, established in Constantinople after the Fourth Crusade (1204) and lasting until the city was recovered by the Byzantine Greeks in 1261 ...

, Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

. He was deposed from his rule of Chios by a Byzantine expedition in 1329, and imprisoned in Constantinople until 1337. Martino then returned to Italy, where he was named the Genoese ambassador to the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

. In 1343 he was named commander of the Papal

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

squadron in the Smyrniote crusade

The Smyrniote crusades (1343–1351) were two Crusades sent by Pope Clement VI against the Emirate of Aydin under Umur Bey which had as their principal target the coastal city of Smyrna in Asia Minor.

The first Smyrniote crusade was the brainch ...

against Umur Bey, ruler of the Emirate of Aydin

The Aydinids or Aydinid dynasty (Modern Turkish: ''Aydınoğulları'', ''Aydınoğulları Beyliği'', ota, آیدین اوغوللاری بیلیغی), also known as the Principality of Aydin and Beylik of Aydin (), was one of the Anatolia ...

, and participated in the storming of Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

in October 1344. He was killed, along with several other of the crusade's leaders, in a Turkish attack on 17 January 1345.

Life

Lord of Chios and wars against the Turks

Martino Zaccaria was a scion of the GenoeseZaccaria

The Zaccaria family was an ancient and noble Genoese dynasty that had great importance in the development and consolidation of the Republic of Genoa in the thirteenth century and in the following period. The Zaccarias were characterized by, accor ...

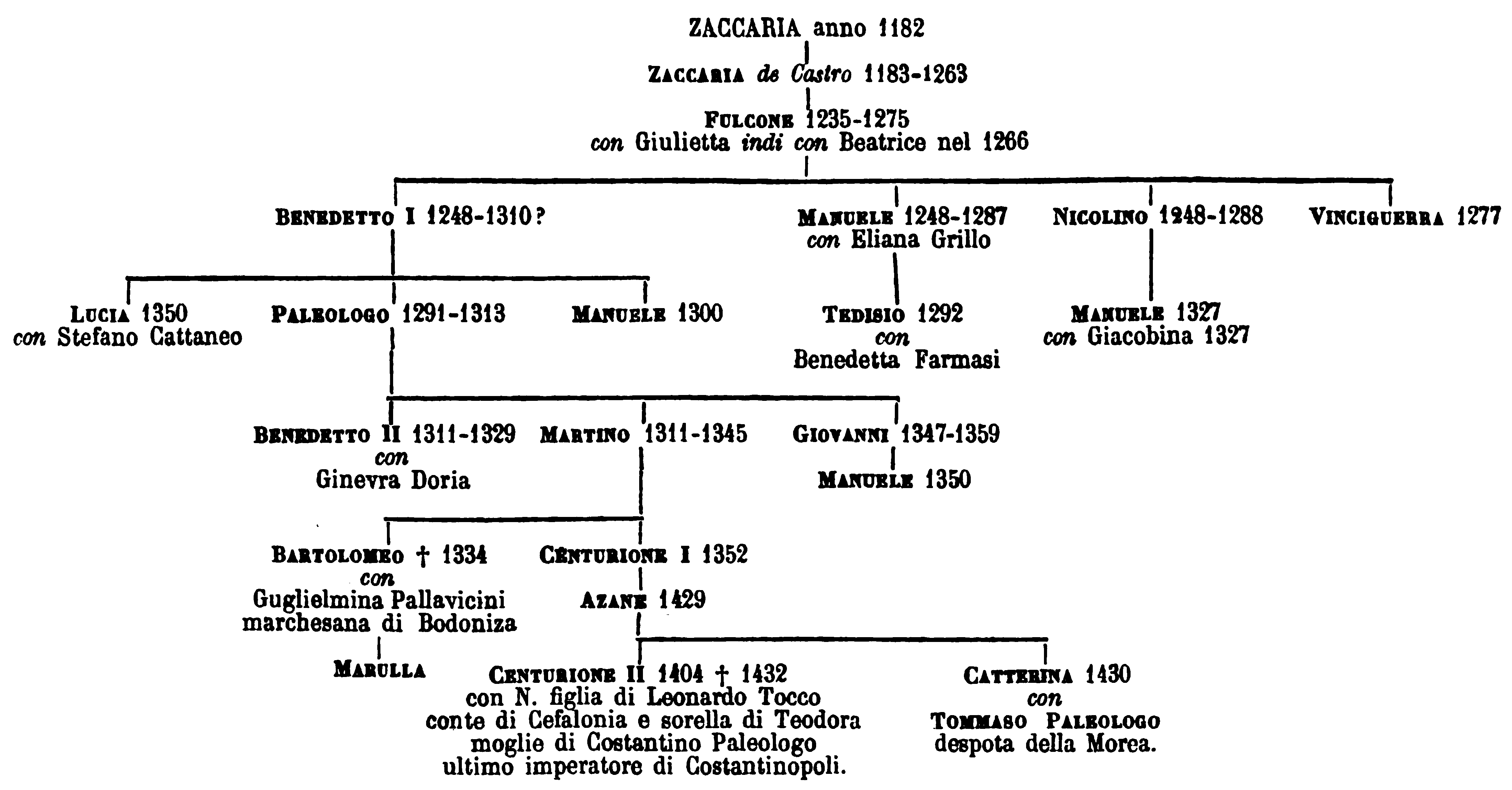

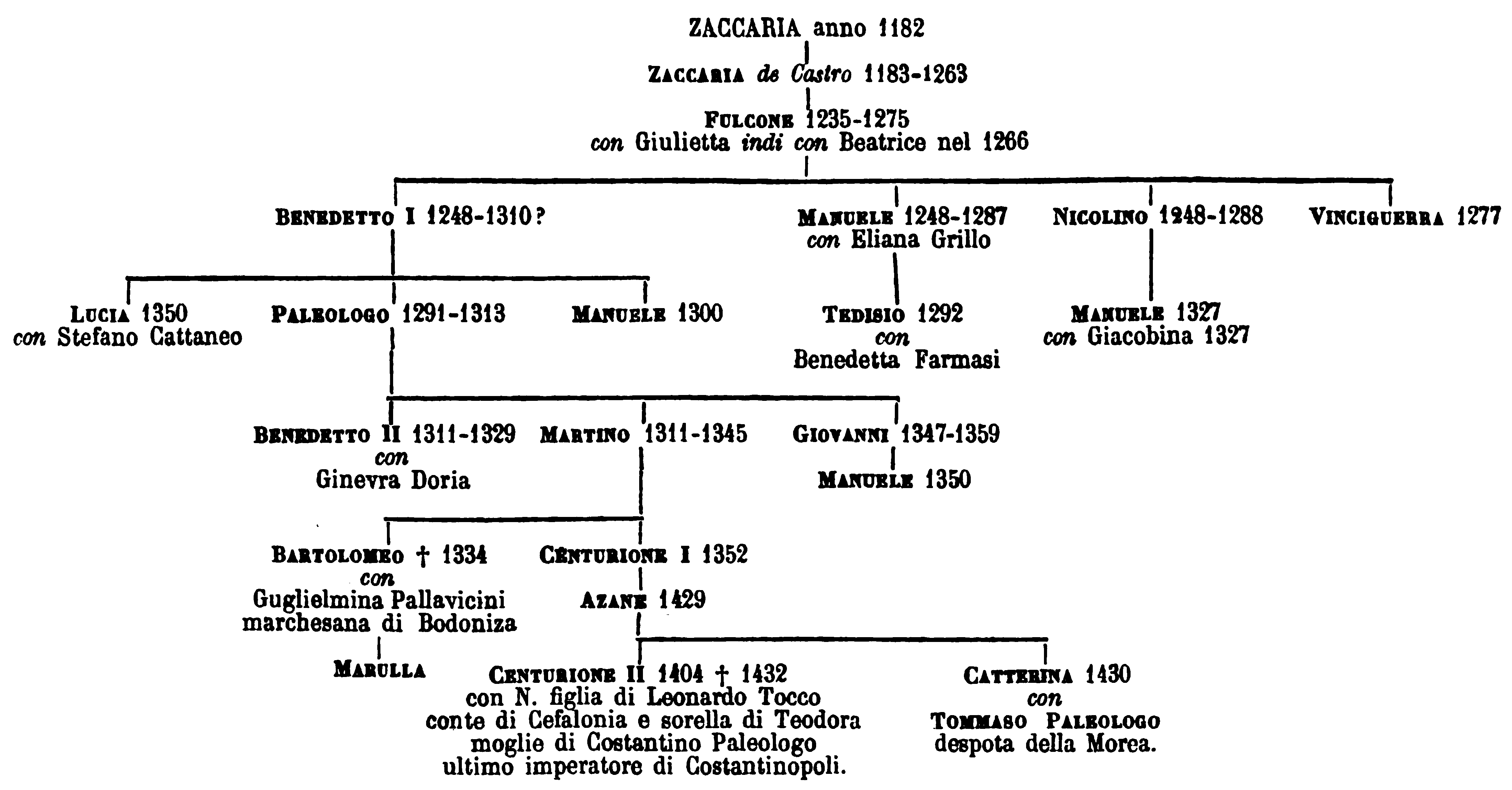

family. Some modern sources give conflicting views about his father, either said to be Paleologo Zaccaria,Domenico Promis, "La Zecca di Scio durante il Dominio dei Genovesi", Torino, 1865, p 19 or Nicolino Zaccaria. He may accordingly have been either a grandson or a nephew to Benedetto I Zaccaria Benedetto I Zaccaria (c. 1235 – 1307) was an Italian admiral of the Republic of Genoa. He was the Lord of Phocaea (from 1288) and first Lord of Chios (from 1304), and the founder of Zaccaria fortunes in Byzantine and Latin Greece. He was, at di ...

, lord of Chios

Chios (; el, Χίος, Chíos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mastic ...

and of Phocaea

Phocaea or Phokaia (Ancient Greek: Φώκαια, ''Phókaia''; modern-day Foça in Turkey) was an ancient Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northern ...

on the Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

n coast. Benedetto I had captured Chios from the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

in 1304, citing the island's vulnerability to Turkish raids. His occupation was acknowledged by the impotent Byzantine emperor, Andronikos II Palaiologos, initially for a period of 10 years, but which was then renewed at five-year intervals. Benedetto died in 1307 and was succeeded in Chios by his son, Paleologo Zaccaria. When he died childless in 1314, the island passed to Martino and his brother, Benedetto II. Chios was a small but wealthy domain, with an annual income of 120,000 gold '' hyperpyra''. Over the next few years, Martino made it the core of a small realm encompassing several islands off the shore of Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, including Samos

Samos (, also ; el, Σάμος ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate ...

and Kos

Kos or Cos (; el, Κως ) is a Greek island, part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese by area, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 36,986 (2021 census), ...

.

As lord of Chios, Martino and Benedetto fought with distinction against the Turkish pirates, who made their appearance in the Aegean in the early years of the 14th century. In 1304, the capture of Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

by the emirate of Menteshe

__NOTOC__

Menteshe ( ota, منتشه, tr, Menteşe) was the first of the Anatolian beyliks, the frontier principalities established by the Oghuz Turks after the decline of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum. Founded in 1260/1290, it was named for i ...

had sparked the Genoese occupation of Chios, and raids against the Aegean islands intensified over the next years. The Emirate of Aydin

The Aydinids or Aydinid dynasty (Modern Turkish: ''Aydınoğulları'', ''Aydınoğulları Beyliği'', ota, آیدین اوغوللاری بیلیغی), also known as the Principality of Aydin and Beylik of Aydin (), was one of the Anatolia ...

soon emerged as the chief Turkish maritime emirate, especially under the leadership of Umur Bey, while the Zaccaria, along with the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

, became the two main Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

antagonists of the Turkish pirates. The Zaccaria are reported to have maintained a thousand infantry, a hundred horsemen and a couple of galley

A galley is a type of ship that is propelled mainly by oars. The galley is characterized by its long, slender hull, shallow draft, and low freeboard (clearance between sea and gunwale). Virtually all types of galleys had sails that could be used ...

s on constant alert. In 1317, they lost the citadel of Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

on the Anatolian coast to the Aydinids, but continued to hold on to the lower city until 1329, when Umur Bey captured it. In 1319, however, Martino Zaccaria participated with seven ships in a Hospitaller fleet that scored a crushing victory over an Aydinid fleet from Ephesus. By the end of his rule on Chios, Martino is said to have taken captive or slain more than 10,000 Turks, and received an annual tribute in order not to attack them. His constant efforts against the Turkish pirates earned him great praise by contemporary Latin writers, who wrote that if not for his vigilance, "neither man, nor woman, nor dog, nor cat, nor any live animal could have remained in any of the neighbouring islands". Martino also intervened to stop the slave trade carried out by the Genoese of Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, for which he was praised by Pope John XXII. In exchange, the Pope granted him the right to export mastic

Mastic may refer to:

Adhesives and pastes

*Mastic (plant resin)

*Mastic asphalt, or asphalt, is a sticky, black and highly viscous liquid

* Mastic cold porcelain, or salt ceramic, is a traditional salt-based modeling clay.

*Mastic, high-grade con ...

to Egypt—an exemption to the papal ban on trade with the Mamluks of Egypt

The Mamluk Sultanate ( ar, سلطنة المماليك, translit=Salṭanat al-Mamālīk), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (western Arabia) from the mid-13th to early 16t ...

—and proposed that the Zaccaria be given command of the Latin fleets in the Aegean.

Martino's prestige rose further when he also became one of the most important feudatories

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain. ...

in the Principality of Achaea

The Principality of Achaea () or Principality of Morea was one of the three vassal states of the Latin Empire, which replaced the Byzantine Empire after the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade. It became a vassal of the Kingdom ...

. Shortly after 1316, he bought the rights to the Barony of Chalandritsa from Aimon of Rans, although in a document of 1324 it appears that he possessed only half of it, the other being held by Peter dalle Carceri Peter dalle Carceri ( it, Pietro dalle Carceri, died 1340) was a Triarchy of Negroponte, Triarch of Euboea and Barony of Arcadia, Baron of Arcadia. He was descended from the noble Dalle Carceri family, son of Grapozzo dalle Carceri and Beatrice of V ...

. Martino added to his domains when he married Jacqueline de la Roche Jacqueline de la Roche (d. after 1329), was sovereign baroness of Veligosti and Damala in 1308-1329, from 1311 in co-regency with her spouse.

Life

She was the daughter and heiress of Renaud de la Roche, and as such the last heiress of the de la ...

, related to the De la Roche

The De la Roche family is a French noble family named for La Roche-sur-l'Ognon that founded the Duchy of Athens of the early 13th century.

People

*Alice de la Roche, (Unknown-1282) Lady of Beirut, Regent of Beirut

* Guy I de la Roche, (1205–1 ...

dukes of Athens

The Duchy of Athens (Greek: Δουκᾶτον Ἀθηνῶν, ''Doukaton Athinon''; Catalan: ''Ducat d'Atenes'') was one of the Crusader states set up in Greece after the conquest of the Byzantine Empire during the Fourth Crusade as part of t ...

and heiress of the Barony of Veligosti–Damala. Martino's elevated standing was now recognized by Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

, titular Latin emperor of Constantinople

The Latin Emperor was the ruler of the Latin Empire, the historiographical convention for the Crusader realm, established in Constantinople after the Fourth Crusade (1204) and lasting until the city was recovered by the Byzantine Greeks in 1261 ...

, who in 1325 named him "King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

and Despot of Asia Minor" and gave him as fiefs the islands of Chios, Samos, Kos, and Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( el, Λέσβος, Lésvos ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece. It is separated from Anatolia, Asia Minor ...

—which formed part of the Latin emperors' personal domain by the Treaty of Viterbo

The Treaty of Viterbo (or the Treaties of Viterbo) was a pair of agreements made by Charles I of Sicily with Baldwin II of Constantinople and William II Villehardouin, Prince of Achaea, on 24 and 27 May 1267, which transferred much of the rights to ...

—as well as Ikaria

Icaria, also spelled Ikaria ( el, Ικαρία), is a Greek island in the Aegean Sea, 10 nautical miles (19 km) southwest of Samos. According to tradition, it derives its name from Icarus, the son of Daedalus in Greek mythology, who was b ...

, Tenedos

Tenedos (, ''Tenedhos'', ), or Bozcaada in Turkish, is an island of Turkey in the northeastern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively, the island constitutes the Bozcaada district of Çanakkale Province. With an area of it is the third l ...

, Oinousses

Oinousses ( el, Οινούσσες, alternative forms: ''Aignousa'' (Αιγνούσα) or ''Egnousa'' (Εγνούσα)) is a barren cluster of 1 larger and 8 smaller islands some off the north-east coast of the Greek island of Chios and west of ...

and Marmara Island

Marmara Island ( ) is a Turkish island in the Sea of Marmara. With an area of it is the largest island in the Sea of Marmara and is the second largest island of Turkey after Gökçeada (older name in Turkish: ; el, Ίμβρος, links=no ''Im ...

. This award was mostly symbolic, as except for the first three, which the Zaccaria already controlled, the others were in the hands of the Byzantines or the Turks. In exchange, Martino promised to aid with 500 horsemen in Philip's hoped-for, but never to be realized, expedition to recover Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

from the Byzantines.

Byzantine recovery of Chios

If these ties to the Latin Emperor provoked displeasure at the Byzantine court, for the time being relations remained good: the lease of Chios was renewed in 1324, and in 1327 Martino took part in alliance negotiations between the Byzantines and the

If these ties to the Latin Emperor provoked displeasure at the Byzantine court, for the time being relations remained good: the lease of Chios was renewed in 1324, and in 1327 Martino took part in alliance negotiations between the Byzantines and the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

. At the same time, however, Martino's behaviour became increasingly assertive: he ousted his brother as co-ruler of Chios and began minting coins in his own name. In 1328, the rise of a new and energetic emperor, Andronikos III Palaiologos

, image = Andronikos_III_Palaiologos.jpg

, caption = 14th-century miniature. Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek.

, succession = Byzantine emperor

, reign = 24 May 1328 – 15 June 1341

, coronation = ...

, to the Byzantine throne, marked a turning-point in relations. One of the leading Chian nobles, Leo Kalothetos, went to meet the new emperor and his chief minister, John Kantakouzenos

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Ángelos Palaiológos Kantakouzēnós''; la, Johannes Cantacuzenus; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under And ...

, to propose a reconquest of the island. Andronikos III readily agreed. On the pretext of Martino's unauthorized building of a new fortress on the island, the emperor sent him a letter in which he ordered him to cease construction, and to present himself in Constantinople in the next year in order to renew the island's lease. Martino haughtily rejected the demands and accelerated construction, but now his deposed brother Benedetto lodged a complaint with the emperor claiming the one-half share of the island's revenues that was his due. With these events as an excuse, in autumn 1329 Andronikos III assembled a fleet of 105 vessels—including the forces of the Latin Duke of Naxos

The Duchy of the Archipelago ( el, Δουκάτο του Αρχιπελάγους, it, Ducato dell'arcipelago), also known as Duchy of Naxos or Duchy of the Aegean, was a maritime state created by Venetian interests in the Cyclades archipelago ...

, Nicholas I Sanudo

Nicholas I Sanudo (or ''Niccolò''; died 1341) was the fifth Duke of the Archipelago from 1323 to his death. He was the son and successor of William I of the House of Sanudo.

Nicholas fought under his brother-in-law Walter, Duke of Athens, at th ...

—and sailed to Chios.

Even after the imperial fleet reached the island, Andronikos III offered to let Martino keep his possessions in exchange for the installation of a Byzantine garrison and the payment of an annual tribute, but Martino refused. He sank his three galleys in the harbour, forbade the Greek population to bear arms and locked himself with 800 men in his citadel, where he raised his own banner instead of the emperor's. His will to resist was broken, however, when Benedetto surrendered his own fort to the Byzantines, and when he saw the locals welcoming them, he was soon forced to surrender. The emperor spared his life, even though the Chians demanded his execution, and took him prisoner to Constantinople. Martino's wife and relatives were allowed to go free with their movable wealth, while most of the Zaccaria adherents chose to stay on the island as imperial officials. Benedetto was offered the island's governorship, but he obstinately demanded to receive it as a personal possession in the same way as his brother had held it, a concession the emperor was unwilling to grant. Benedetto retired to the Genoese colony of Galata

Galata is the former name of the Karaköy neighbourhood in Istanbul, which is located at the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The district is connected to the historic Fatih district by several bridges that cross the Golden Horn, most notabl ...

, from where a few years later he made an unsuccessful attempt to reclaim Chios; he died soon after. Andronikos III appointed Kalothetos as the new governor of Chios, and followed up his success by sailing to Phocaea, forcing it to acknowledge his suzerainty.

Later life and the Smyrniote crusade

Martino was released in 1337 at the intercession of the Pope andPhilip VI of France

Philip VI (french: Philippe; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (french: le Fortuné, link=no) or the Catholic (french: le Catholique, link=no) and of Valois, was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 1328 ...

, and was offered a military command and some castles by the emperor as compensation. He then returned to his hometown, Genoa, and was named the city's ambassador to the Holy See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome ...

. In September 1343, he was appointed to command the four papal galleys in the crusade

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were i ...

against Umur Bey, under the overall command of the titular Latin Patriarch of Constantinople

The Latin Patriarchate of Constantinople was an office established as a result of the Fourth Crusade and its conquest of Constantinople in 1204. It was a Roman Catholic replacement for the Eastern Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople ...

, Henry of Asti. In view of Zaccaria's character, the Pope expressly warned Henry of Asti not to allow him to divert the crusade in a bid to recover Chios, and authorized Henry to replace Zaccaria if he deemed it necessary. The crusade scored a swift and unexpected success: Umur Bey was caught off guard, and the crusaders recaptured the lower town of Smyrna on 28 October 1344. The citadel remained in Turkish hands, however, and the crusaders' position remained precarious. With Venetian aid, they fortified the lower town to enable them to resist Umur's counterattack. The emir bombarded the lower town with mangonel

The mangonel, also called the traction trebuchet, was a type of trebuchet used in Ancient China starting from the Warring States period, and later across Eurasia by the 6th century AD. Unlike the later counterweight trebuchet, the mangonel o ...

s, but the crusaders managed to sortie and destroy them, effectively breaking the siege. To celebrate this feat, Henry of Asti decided, against the advice of the other crusader leaders, to hold mass in the city's former cathedral, which lay in the no-man's-land between the citadel and the crusader-held lower town. The Turks attacked during the service, on 17 January 1345, and killed Zaccaria, Henry of Asti and other crusader leaders present.

Family

Martino Zaccaria married, probably some time before 1325, Jacqueline de la Roche. An earlier conjecture of

Martino Zaccaria married, probably some time before 1325, Jacqueline de la Roche. An earlier conjecture of Karl Hopf Karl Hopf may refer to:

* Karl Hopf (historian)

Karl Hopf (Hamm, Westphalia, February 19, 1832 – Wiesbaden, August 23, 1873) or Carl Hermann Friedrich Johann Hopf was a historian and an expert in Medieval Greece, both Byzantine and Frankish.

...

about a first marriage to a daughter of George I Ghisi George I Ghisi ( it, Giorgio Ghisi) (died 15 March 1311) was a Latinokratia, Latin feudal lord in medieval Greece.

A son of Bartholomew I Ghisi, through his first marriage to a daughter of Guy II of Dramelay he was Baron of Chalandritsa in the Pri ...

, heir to the lordship of Tinos

Tinos ( el, Τήνος ) is a Greek island situated in the Aegean Sea. It is located in the Cyclades archipelago. The closest islands are Andros, Delos, and Mykonos. It has a land area of and a 2011 census population of 8,636 inhabitants.

Tinos ...

and Mykonos

Mykonos (, ; el, Μύκονος ) is a Greek island, part of the Cyclades, lying between Tinos, Syros, Paros and Naxos. The island has an area of and rises to an elevation of at its highest point. There are 10,134 inhabitants according to the ...

, has since been discarded.

From his marriage, Martino had two sons:

* Bartolommeo Zaccaria (died 1334). By right of his wife, he was Margrave of Bodonitsa The margraviate or marquisate of Bodonitsa (also Vodonitsa or Boudonitza; el, Μαρκιωνία/Μαρκιζᾶτον τῆς Βοδονίτσας), today Mendenitsa, Phthiotis (180 km northwest of Athens), was a Frankish state in Greece fo ...

.

* Centurione I Zaccaria Centurione I Zaccaria (1336–1376) was a powerful noble in the Principality of Achaea in Frankish Greece. In 1345 he succeeded his father, Martino Zaccaria, as baron of Damala and lord of one half of the Barony of Chalandritsa, and in 1359 he ac ...

(died 1382). As the sole surviving son, he inherited his father's fiefs in Morea in 1345. He founded the family's Moreote line, which eventually ascended to the princely title of Achaea under Maria II Zaccaria

Maria II Zaccaria (14th century – after 1404) was a Principality of Achaea, Princess of Achaia.

She was daughter of Centurione I Zaccaria, Lord of Barony of Veligosti, Veligosti–Damala and Barony of Chalandritsa, Chalandritsa. She succeeded ...

and Centurione II Zaccaria

Centurione II Zaccaria (died 1432), scion of a powerful Genoese merchant family established in the Morea, was installed as Prince of Achaea by Ladislaus of Naples in 1404 and was the last ruler of the Latin Empire not under Byzantine suzerainty ...

.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Zaccaria, Martino 1345 deaths 14th-century diplomats 14th-century Genoese people Ambassadors of the Republic of Genoa Ambassadors to the Holy See Barons of Veligosti-Damala Christians of the Crusades Despots (court title) Medieval Aegean Sea Medieval Italian diplomats People killed in action Prisoners of war held by the Byzantine Empire Martino Year of birth unknown Martino Smyrniote crusades 14th-century people of the Principality of Achaea