Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=

Martinican Creole

Antillean Creole (Antillean French Creole, Kreyol, Kwéyòl, Patois) is a French-based creole that is primarily spoken in the Lesser Antilles. Its grammar and vocabulary include elements of Carib, English, and African languages.

Antillean Creol ...

, Matinik or ;

Kalinago

The Kalinago, also known as the Island Caribs or simply Caribs, are an indigenous people of the Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. They may have been related to the Mainland Caribs (Kalina) of South America, but they spoke an unrelated language ...

: or ) is an island and an

overseas department/region and

single territorial collectivity

A single territorial collectivity (french: collectivité territoriale unique) is a chartered subdivision of France that exercises the powers of both a region and a department. This subdivision was introduced in Mayotte in 2011, in French Guian ...

of France. An integral part of the

French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, Martinique is located in the

Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc betwe ...

of the West Indies in the eastern

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

. It has a land area of and a population of 364,508 inhabitants as of January 2019.

[Populations légales 2019: 972 Martinique]

INSEE One of the

Windward Islands

french: Îles du Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Windward Islands. Clockwise: Dominica, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Grenada.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean SeaNorth ...

, it is directly north of

Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerindian ...

, northwest of

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

and south of

Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographically ...

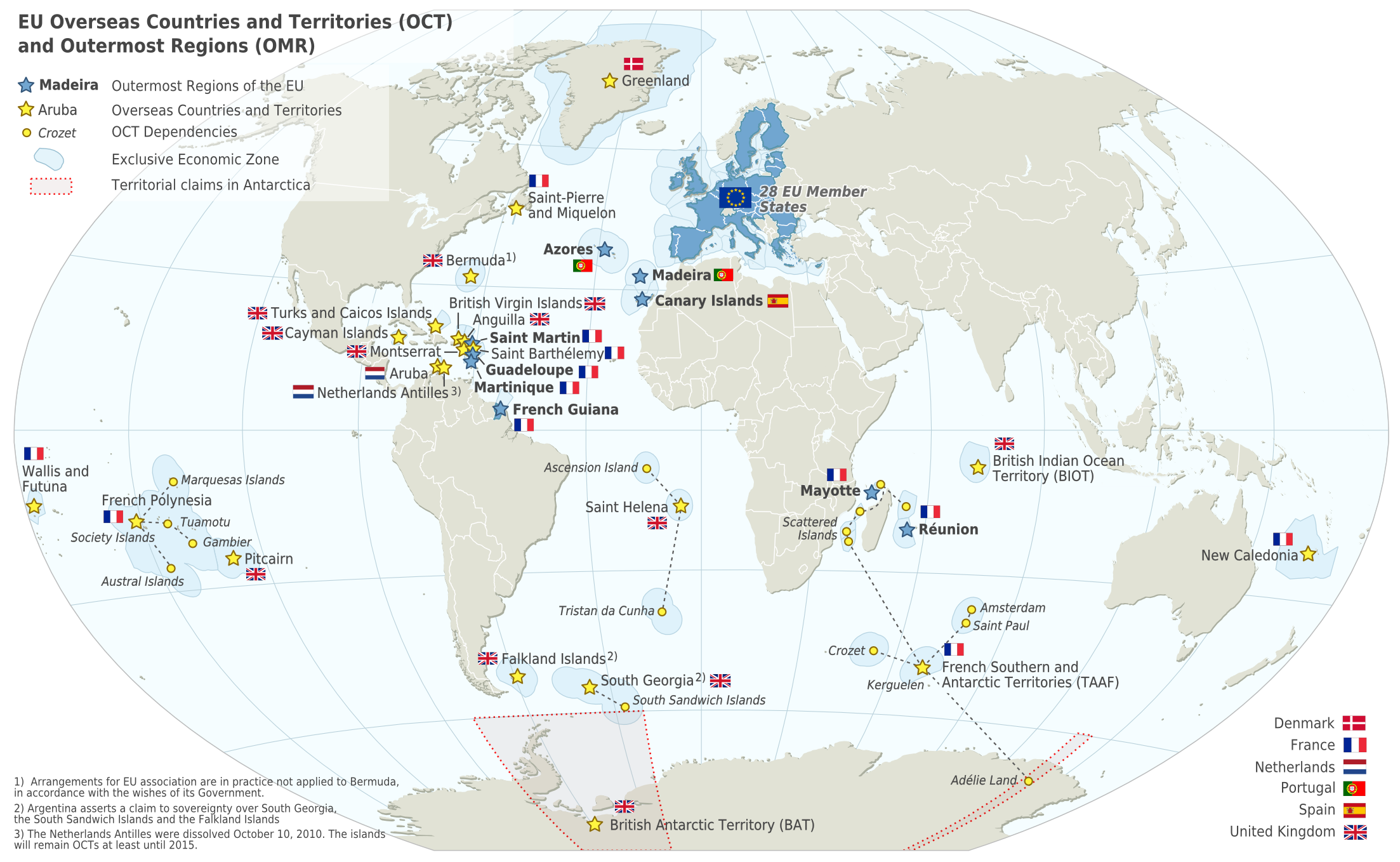

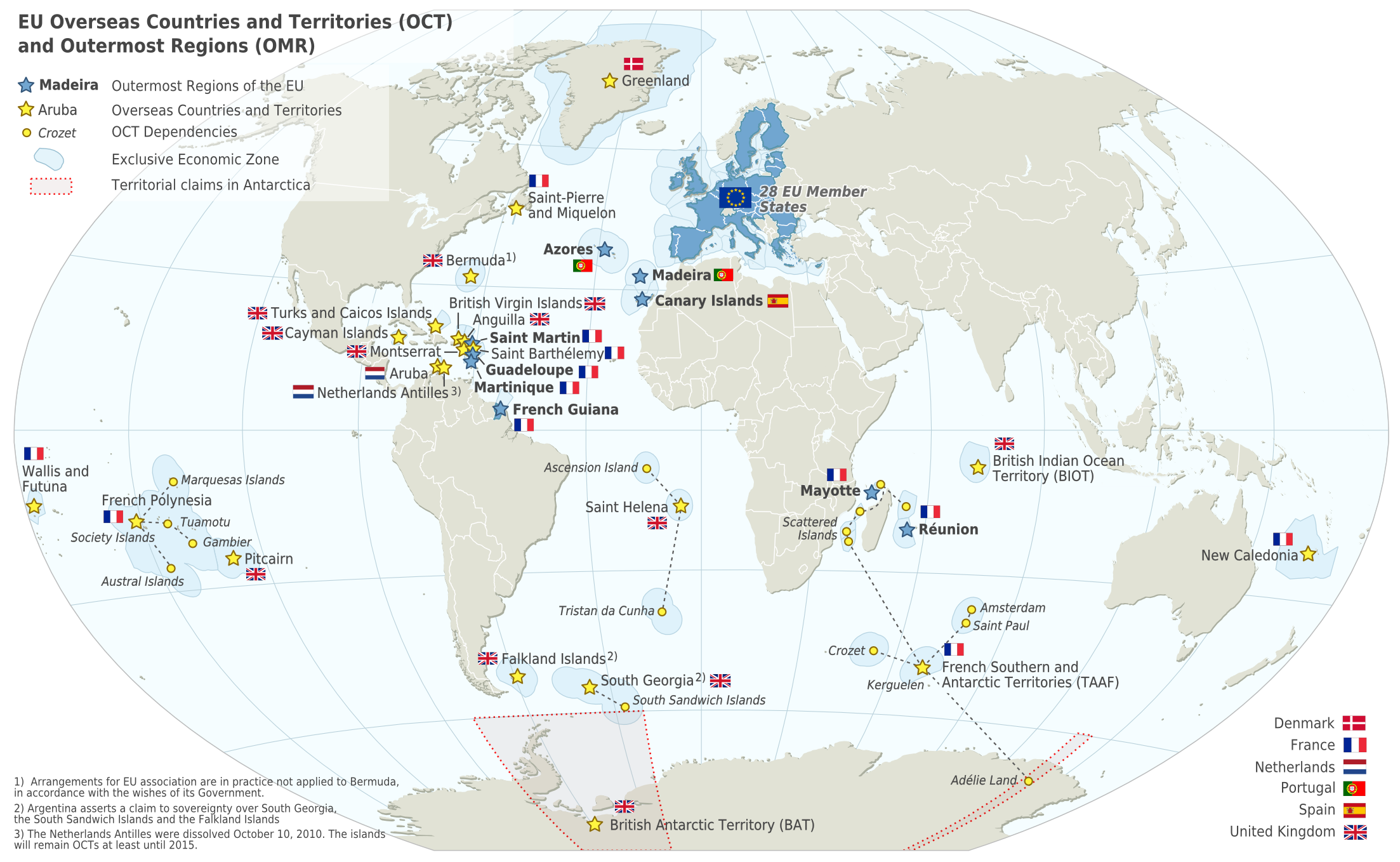

. Martinique is an Outermost Region and a

special territory of the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

; the currency in use is the

euro

The euro ( symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 19 out of the member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 340 million citizens . ...

. Virtually the entire population speaks both French (the sole official language) and

Martinican Creole

Antillean Creole (Antillean French Creole, Kreyol, Kwéyòl, Patois) is a French-based creole that is primarily spoken in the Lesser Antilles. Its grammar and vocabulary include elements of Carib, English, and African languages.

Antillean Creol ...

.

Etymology

It is thought that Martinique is a corruption of the

Taíno

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

name for the island (/, meaning 'island of flowers', or , 'island of women'), as relayed to

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

when he visited the island in 1502.

According to historian Sydney Daney, the island was called or by the

Caribs

“Carib” may refer to:

People and languages

*Kalina people, or Caribs, an indigenous people of South America

**Carib language, also known as Kalina, the language of the South American Caribs

*Kalinago people, or Island Caribs, an indigenous pe ...

, which means 'the island of iguanas'.

History

Pre-European contact and early colonial periods

The island was occupied first by

Arawaks

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, wh ...

, then by

Caribs

“Carib” may refer to:

People and languages

*Kalina people, or Caribs, an indigenous people of South America

**Carib language, also known as Kalina, the language of the South American Caribs

*Kalinago people, or Island Caribs, an indigenous pe ...

. The Arawaks were described as gentle timorous Indians and the Caribs as ferocious cannibal warriors. The Arawaks came from Central America in the 1st century AD and the Caribs came from the Venezuelan coast around the 11th century.

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

charted Martinique (without landing) in 1493, during his first voyage, but Spain had little interest in the territory.

Columbus landed during a later voyage, on 15 June 1502, after a 21-day

trade wind

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisph ...

passage

Passage, The Passage or Le Passage may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Films

* Passage (2008 film), ''Passage'' (2008 film), a documentary about Arctic explorers

* Passage (2009 film), ''Passage'' (2009 film), a short movie about three sisters

* ...

, his fastest ocean voyage.

He spent three days there refilling his water casks, bathing and washing laundry.

The indigenous people Columbus encountered called Martinique ‘Matinino’. He was told by indigenous people of

San Salvador that ‘the island of Matinino was entirely populated by women on whom the Caribs descended at certain seasons of the year; and if these women bore sons they were entrusted to the father to bring up.’

On 15 September 1635,

Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc

Pierre Belain, sieur d'Esnambuc (; 1585–1636) was a French trader and adventurer in the Caribbean, who established the first permanent French colony, Saint-Pierre, on the island of Martinique in 1635.

Biography Youth

Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc wa ...

, French governor of the island of

St. Kitts

Saint Kitts, officially the Saint Christopher Island, is an island in the West Indies. The west side of the island borders the Caribbean Sea, and the eastern coast faces the Atlantic Ocean. Saint Kitts and the neighbouring island of Nevis cons ...

, landed in the harbour of

St. Pierre with 80-150 French settlers after being driven off St. Kitts by the English. D'Esnambuc claimed Martinique for the French king

Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown ...

and the French "

Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique The Company of the American Islands (french: Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique) was a French chartered company that in 1635 took over the administration of the French portion of ''Saint-Christophe island'' (Saint Kitts) from the Compagnie de Saint- ...

" (Company of the American Islands), and established the first European settlement at Fort Saint-Pierre (now St. Pierre).

D'Esnambuc died in 1636, leaving the company and Martinique in the hands of his nephew,

Jacques Dyel du Parquet

Jacques Dyel du Parquet (1606 – 3 January 1658) was a French soldier who was one of the first governors of Martinique.

He was appointed governor of the island for the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique in 1636, a year after the first French set ...

, who in 1637 became governor of the island.

In 1636, in the first of many skirmishes, the indigenous Caribs rose against the settlers to drive them off the island. The French successfully repelled the natives and forced them to retreat to the eastern part of the island, on the Caravelle Peninsula in the region then known as the Capesterre. When the Caribs revolted against French rule in 1658, the governor

Charles Houël du Petit Pré Charles Houël du Petit Pré (1616—22 April 1682) was a French governor of Guadeloupe from 1643 to 1664. He was also knight and lord.

He became, by a royal proclamation dated August 1645, the first of the island judicial officer. He is named Marq ...

retaliated with war against them. Many were killed, and those who survived were taken captive and expelled from the island. Some Caribs fled to

Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographically ...

or

St. Vincent

Saint Vincent may refer to:

People Saints

* Vincent of Saragossa (died 304), a.k.a. Vincent the Deacon, deacon and martyr

* Saint Vincenca, 3rd century Roman martyress, whose relics are in Blato, Croatia

* Vincent, Orontius, and Victor (died 305) ...

, where the French agreed to leave them at peace.

After the death of du Parquet in 1658, his widow

Marie Bonnard du Parquet

Marie Bonnard du Parquet (died 1659) was the wife of Jacques Dyel du Parquet, one of the first governors of Martinique, who purchased the island in 1650.

When her husband died she tried to act as governor in the name of her children, but was force ...

tried to govern Martinique, but dislike of her rule led King

Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

to take over the sovereignty of the island.

In 1654, Dutch Jews expelled from Portuguese Brazil introduced sugar plantations worked by large numbers of enslaved Africans.

In 1667, the

Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War or the Second Dutch War (4 March 1665 – 31 July 1667; nl, Tweede Engelse Oorlog "Second English War") was a conflict between Kingdom of England, England and the Dutch Republic partly for control over the seas a ...

spilled out into the Caribbean, with Britain

attacking the pro-Dutch French fleet in Martinique, virtually destroying it and further cementing British preeminence in the region. In 1674, the Dutch

attempted to conquer the island, but were repulsed.

Because there were few

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

priests in the French Antilles, many of the earliest French settlers were

Huguenots

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss politica ...

who sought religious freedom. Others were transported there as a punishment for refusing to convert to Catholicism, many of them dying en route. Those who survived were quite industrious and over time prospered, though the less fortunate were reduced to the status of indentured servants. Although edicts from King Louis XIV's court regularly came to the islands to suppress the

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

"heretics", these were mostly ignored by island authorities until Louis XIV's

Edict of Revocation in 1685.

As many of the planters on Martinique were Huguenots suffering under the harsh strictures of the Revocation, they began plotting to emigrate from Martinique with many of their recently arrived brethren. Many of them were encouraged by the Catholics, who looked forward to their departure and the opportunities for seizing their property. By 1688, nearly all of Martinique's French Protestant population had escaped to the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

American colonies or Protestant countries in Europe. The policy decimated the population of Martinique and the rest of the French Antilles and set back their colonisation by decades, causing the French king to relax his policies in the region, which left the islands susceptible to British occupation over the next century.

Post-1688 period

Under governor of the Antilles

Charles de Courbon, comte de Blénac

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

, Martinique served as a home port for French pirates, including

Captain Crapeau,

Étienne de Montauban

Étienne de Montauban (fl. 1691-1695) was a French ''flibustier'' (buccaneer), privateer, and pirate active in the Caribbean and off the west African coast. Frequently referred to as Sieur de Montauban (last name occasionally Montauband), he wrote ...

, and

Mathurin Desmarestz

Mathurin Desmarestz (1653-1700, last name also Demarais) was a French pirate and buccaneer active in the Caribbean, the Pacific, and the Indian Ocean.

History

Born Isaac Veyret (or Vereil) in 1653, son of Isaac Veyret and Esther Pennaud, Mathurin ...

.

[ French language original, as reprinted in ''Le Diable Volant: Une histoire de la flibuste: de la mer des Antilles à l'océan Indien (1688–1700)'' / (''The Flying Devil: A History of the Filibusters: From the Antilles to the Indian Ocean (1688–1700)'').] In later years, pirate

Bartholomew Roberts

)

, type=Pirate

, birth_place = Casnewydd Bach, near Puncheston, Pembrokeshire, Wales, Kingdom of England

, death_place = At sea off of Cape Lopez, Gabon

, allegiance=

, serviceyears=1719–1722

, base of operations= Off the coast of the Americas ...

styled his

jolly roger

Jolly Roger is the traditional English name for the flags flown to identify a pirate ship preceding or during an attack, during the early 18th century (the later part of the Golden Age of Piracy).

The flag most commonly identified as the Jolly ...

as a black flag depicting a pirate standing on two skulls labeled "ABH" and "AMH" for "A Barbadian's Head" and "A Martinican's Head" after governors of those two islands sent warships to capture Roberts.

Martinique was attacked or occupied several times by the British, in 1693,

1759

In Great Britain, this year was known as the ''Annus Mirabilis'', because of British victories in the Seven Years' War.

Events

January–March

* January 6 – George Washington marries Martha Dandridge Custis.

* January 11 &ndas ...

,

1762

Events

January–March

* January 4 – Britain enters the Seven Years' War against Spain and Naples.

* January 5 – Empress Elisabeth of Russia dies, and is succeeded by her nephew Peter III. Peter, an admirer of Frederick t ...

and

1779

Events

January–March

* January 11 – British troops surrender to the Marathas in Wadgaon, India, and are forced to return all territories acquired since 1773.

* January 11 – Ching-Thang Khomba is crowned King of Manip ...

.

Excepting a period from 1802 to 1809 following signing of the

Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on perio ...

, Britain controlled the island for most of the time from 1794 to 1815, when it was traded back to France at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars.

Martinique has remained a French possession since then.

Despite the introduction of successful coffee plantations in the 1720s to Martinique, the first coffee-growing area in the Western hemisphere, as sugar prices declined in the early 1800s, the planter class lost political influence. Slave rebellions in 1789, 1815 and 1822, plus the campaigns of abolitionists such as

Cyrille Bissette

Cyrille Bissette (1795–1858) was a French abolitionist, politician and publisher. A free person of color (''homme de couleur'') from Martinique, his radical activities and publications galvanized the abolition movement in France and its colonies. ...

and

Victor Schœlcher

Victor Schœlcher (; 22 July 1804 – 25 December 1893) was a French abolitionist, writer, politician and journalist, best known for his leading role in the abolition of slavery in France in 1848, during the Second Republic.

Early life

Schœlche ...

, persuaded the French government to end

slavery in the French West Indies in 1848.

As a result, some plantation owners imported workers from India and China.

Despite the abolition of slavery, life scarcely improved for most Martinicans; class and racial tensions exploded into rioting in southern Martinique in 1870 following the arrest of Léopold Lubin, a trader of African ancestry who retaliated after he was beaten by a Frenchman. After several deaths, the revolt was crushed by French militia.

20th–21st centuries

On 8 May 1902,

Mont Pelée

Mont may refer to:

Places

* Mont., an abbreviation for Montana, a U.S. state

* Mont, Belgium (disambiguation), several places in Belgium

* Mont, Hautes-Pyrénées, a commune in France

* Mont, Pyrénées-Atlantiques, a commune in France

* Mont, Sa� ...

erupted and completely destroyed St. Pierre, killing 30,000 people.

Refugees from Martinique travelled by boat to the southern villages of

Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographically ...

, and some of them remained permanently on the island. The only survivor in the town of Saint-Pierre,

Auguste Cyparis, was saved by the thick walls of his prison cell.

Shortly thereafter, the capital shifted to

Fort-de-France

Fort-de-France (, , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Fodfwans) is a Communes of France, commune and the capital city of Martinique, an overseas department and region of France located in the Caribbean. It is also one of the major cities in the ...

, where it remains today.

During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the pro-Nazi

Vichy government

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

controlled Martinique under Admiral

Georges Robert.

German

U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

s used Martinique for refuelling and re-supply during the

Battle of the Caribbean

The Battle of the Caribbean refers to a naval campaign waged during World War II that was part of the Battle of the Atlantic, from 1941 to 1945. German U-boats and Italian submarines attempted to disrupt the Allied supply of oil and other mate ...

. In 1942, 182 ships were sunk in the Caribbean, dropping to 45 in 1943, and five in 1944.

Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

forces took over on the island on

Bastille Day

Bastille Day is the common name given in English-speaking countries to the national day of France, which is celebrated on 14 July each year. In French, it is formally called the (; "French National Celebration"); legally it is known as (; "t ...

, 14 July 1943.

In 1946, the

French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known a ...

voted unanimously to transform the colony into an Overseas Department of France.

Meanwhile, the post-war period saw a growing campaign for full independence; a notable proponent of this was the author

Aimé Césaire

Aimé Fernand David Césaire (; ; 26 June 1913 – 17 April 2008) was a French poet, author, and politician. He was "one of the founders of the Négritude movement in Francophone literature" and coined the word in French. He founded the Par ...

, who founded the

Progressive Party of Martinique

The Martinican Progressive Party (french: Parti progressiste martiniquais, PPM) is a democratic socialist political party in Martinique. It was founded on March 22, 1958 by poet Aimé Césaire after breaking off from the French Communist Party. Th ...

in the 1950s. Tensions boiled over in December 1959 when riots broke out following a racially-charged altercation between two motorists, resulting in three deaths.

In 1962, as a result of this and the global turn against colonialism, the strongly pro-independence OJAM () was formed. Its leaders were later arrested by the French authorities. However, they were later acquitted.

Tensions rose again in 1974, when gendarmes shot dead two striking banana workers.

However the independence movement lost steam as Martinique's economy faltered in the 1970s, resulting in large-scale emigration. Hurricanes in 1979–80 severely affected agricultural output, further straining the economy.

Greater autonomy was granted by France to the island in the 1970s–80s

In 2009, Martinique was convulsed by the

French Caribbean general strikes. Initially focusing on cost-of-living issues, the movement soon took on a racial dimension as strikers challenged the continued economic dominance of the ''

Béké

Béké or beke is an Antillean Creole term to describe a descendant of the early European, usually French, settlers in the French Antilles.

Etymology

The origin of the term is unclear, although it is attested to in colonial documents from as early ...

'', descendants of French European settlers.

President

Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul Stéphane Sarközy de Nagy-Bocsa (; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012.

Born in Paris, he is of Hungarian, Greek Jewish, and French origin. Mayor of Neuilly-sur-Se ...

later visited the island, promising reform.

["Sarkozy offers autonomy vote for Martinique"](_blank)

, AFP While ruling out full independence, which he said was desired neither by France nor by Martinique, Sarkozy offered Martiniquans a referendum on the island's future status and degree of autonomy.

Governance

Like

French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label=French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic ...

, Martinique is a special collectivity (Unique in French) of the French Republic. It is also an

outermost region

The special territories of members of the European Economic Area (EEA) are the 32 special territories of EU member states and EFTA member states which, for historical, geographical, or political reasons, enjoy special status within or outside ...

of the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

. The inhabitants of Martinique are French citizens with full political and legal rights. Martinique sends

four deputies

The Four Deputies ( ar, ٱلنُّوَّاب ٱلْأَرْبَعَة, ') were the four individuals who are believed by the Twelvers to have successively represented their twelfth Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, during his Minor Occultation (874–941 CE ...

to the

French National Assembly

The National Assembly (french: link=no, italics=set, Assemblée nationale; ) is the lower house of the bicameral French Parliament under the Fifth Republic, the upper house being the Senate (). The National Assembly's legislators are known a ...

and two senators to the

French Senate

The Senate (french: Sénat, ) is the upper house of the French Parliament, with the lower house being the National Assembly (France), National Assembly, the two houses constituting the legislature of France. The French Senate is made up of 34 ...

.

On 24 January 2010, during a referendum, the inhabitants of Martinique approved by 68.4% the change to be a "special (unique) collectivity" within the framework of article 73 of the French Republic's Constitution. The new council replaces and exercises the powers of both the

General Council General council may refer to:

In education:

* General Council (Scottish university), an advisory body to each of the ancient universities of Scotland

* General Council of the University of St Andrews, the corporate body of all graduates and senio ...

and the

regional council.

Administrative divisions

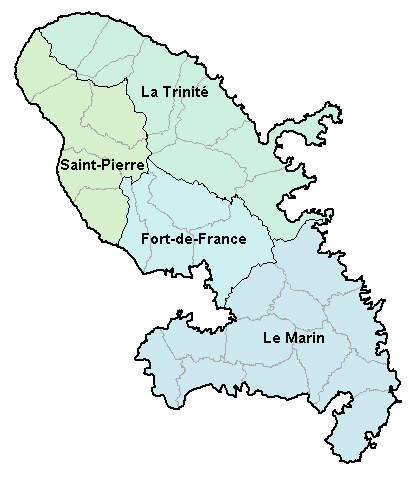

Martinique is divided into four ''

arrondissements

An arrondissement (, , ) is any of various administrative divisions of France, Belgium, Haiti, certain other Francophone countries, as well as the Netherlands.

Europe

France

The 101 French departments are divided into 342 ''arrondissements'', ...

'' and 34 ''

communes

An intentional community is a voluntary residential community which is designed to have a high degree of social cohesion and teamwork from the start. The members of an intentional community typically hold a common social, political, religious, ...

''. It had also been divided into 45 ''

cantons

A canton is a type of administrative division of a country. In general, cantons are relatively small in terms of area and population when compared with other administrative divisions such as counties, departments, or provinces. Internationally, t ...

'', but these were abolished in 2015. The four arrondissements of the island, with their respective locations, are as follows:

* Fort-de-France, is the prefecture of Martinique. It takes up the central zone of the island. It includes four communes. In 2019, the population was 152,102.

[ Besides the capital, it includes the communities of Saint-Joseph and ]Schœlcher

Schœlcher (; Martinican Creole: ) is a town and the fourth-largest commune in the French overseas department of Martinique. The town was named Case-Navire until 1889, when it was renamed in honor of French abolitionist writer Victor Schœlcher.

...

.

* La Trinité, one of the three subprefectures on the island, occupies the northeast region. It has ten communes. In 2019, the population was 75,238.Basse-Pointe

Basse-Pointe (; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Baspwent) is a town and commune in the French overseas department and region, and island of Martinique.

Geography Climate

Basse-Pointe has a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classificatio ...

, Le Gros-Morne, Le Lorrain

Le Lorrain (; Martinican Creole: ) is a town and commune in the French overseas region and department of Martinique.

Population

Personalities

*Raphaël Confiant

*Jean Bernabé

See also

*Communes of the Martinique department

The following is ...

, Macouba

Macouba () is a village and commune in the French overseas department of Martinique.

Geography Climate

Macouba has a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification ''Af''). The average annual temperature in Macouba is . The avera ...

, Le Marigot

Le Marigot (; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Mawigo) is a village and communes of France, commune in the overseas departments of France, French overseas department of Martinique.

Population

See also

*Communes of Martinique

References

Extern ...

, Le Robert

Le Robert (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Wobè) is a town and the third-largest commune in the French overseas department of Martinique. It is located in the northeastern (Atlantic) side of the island of Martinique. It contains the Sainte Ros ...

and Sainte-Marie.

* Le Marin

Le Marin (; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Maren or ) is a town and commune in the French overseas department of Martinique.

Population

Points of interest

In Le Marin there is Église du Marin, an old church built in 1766. It contains a marbl ...

, the second subprefecture of Martinique, makes up the southern part of the island and is composed of twelve communes. In 2019, the population was 114,824.Le Diamant

Le Diamant (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Dianman or , ) is a town and commune in the French overseas department of Martinique.

Geography

The town of Le Diamant is situated in southwestern Martinique, where the Diamond Rock is.

Population

Se ...

, Ducos, Le François

Le François ( gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Fwanswa) is a town and commune in the arrondissement of Le Marin on Martinique, from the island capital of Fort-de-France.

Geography Climate

Le François has a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen climat ...

, Rivière-Pilote

Rivière-Pilote (; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Lavièpilot or ) is a town and commune in the French overseas department of Martinique.

The village is situated on the southern end of Martinique, between the village of Sainte-Luce and the tow ...

, Rivière-Salée

Rivière-Salée (, literally ''Salty River''; Martinican Creole: , or ) is a town and commune in the French overseas department and region of Martinique.

Population

Notable people

* André Lesueur (born 1947), mayor of Rivière-Salée and fo ...

, Sainte-Anne, Sainte-Luce, Saint-Esprit, Les Trois-Îlets

Les Trois-Îlets (; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Twazilé) is a town and commune in the French overseas department and region of Martinique.

It was the birthplace of Joséphine (1763–1814), who married Napoleon Bonaparte and became Empress ...

, and Le Vauclin

Le Vauclin (; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Voklen) is a commune and town in the French overseas department and region, and island of Martinique.

Geography

Located in the southeast of the island, its neighboring towns are Le François, Saint- ...

.

* Saint-Pierre, is the third subprefecture of the island. It comprises eight communes, lying in the northwest of Martinique. In 2019, the population was 22,344.Le Carbet

Le Carbet (, ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Kabé) is a village and commune in the French overseas department of Martinique.

Population

See also

*Communes of Martinique

*Paul Gauguin Interpretation Centre

The Paul Gauguin Interpretation Ce ...

, Case-Pilote-Bellefontaine, Le Morne-Rouge

Le Morne-Rouge (; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Mònwouj) is a commune and town in the French overseas department and island of Martinique.

Geography

Le Morne-Rouge is the wettest town of Martinique, It is situated on a plateau between Mount Pe ...

, and Le Prêcheur

Le Prêcheur (; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Pwéchè) is a village and commune in the French overseas department, region and island of Martinique.

Asthon Tardon (1882-1944), father of Manon Tardon, was mayor of the community; their family's ...

.

Representation of the State

The prefecture

A prefecture (from the Latin ''Praefectura'') is an administrative jurisdiction traditionally governed by an appointed prefect. This can be a regional or local government subdivision in various countries, or a subdivision in certain international ...

of Martinique is Fort-de-France. The three sub-prefectures are Le Marin, Saint-Pierre and La Trinité. The French State is represented in Martinique by a prefect (Stanislas Cazelles since 5 February 2020), and by two sub-prefects in Le Marin (Corinne Blanchot-Prosper) and La Trinité / Saint-Pierre (Nicolas Onimus, appointed on 20 May 2020).

The prefecture was criticized for racism following the publication on its Twitter account of a poster calling for physical distancing against the coronavirus

Coronaviruses are a group of related RNA viruses that cause diseases in mammals and birds. In humans and birds, they cause respiratory tract infections that can range from mild to lethal. Mild illnesses in humans include some cases of the com ...

and showing a black man and a white man separated by pineapples.

Institutions

The President of the Executive Council of Martinique is Serge Letchimy as of 2 July 2021.

The Executive Council of Martinique is composed of nine members (a president and eight executive councilors).

The deliberative assembly of the territorial collectivity is the Assembly of Martinique, composed of 51 elected members and chaired by Lucien Saliber as of 2 July 2021.

The advisory council of the

The President of the Executive Council of Martinique is Serge Letchimy as of 2 July 2021.

The Executive Council of Martinique is composed of nine members (a president and eight executive councilors).

The deliberative assembly of the territorial collectivity is the Assembly of Martinique, composed of 51 elected members and chaired by Lucien Saliber as of 2 July 2021.

The advisory council of the territorial collectivity

A territorial collectivity (french: collectivité territoriale, previously '), or territorial authority, is a chartered subdivision of France with recognized governing authority. It is the generic name for any subdivision (subnational entity) wit ...

of Martinique is the Economic, Social, Environmental, Cultural and Educational Council of Martinique (Conseil économique, social, environnemental, de la culture et de l'éducation de Martinique), composed of 68 members. Its president is Justin Daniel since 20 May 2021.

National representation

Martinique has been represented since 17 June 2017, in the National Assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

by four deputies (Serge Letchimy, Jean-Philippe Nilor, Josette Manin and Manuéla Kéclard-Mondésir) and in the Senate by two senators (Maurice Antiste

Maurice Antiste (born 22 June 1953 in Martinique) is a French politician who was elected to the Senate (France), French Senate on 25 September 2011, representing the department of Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, ...

and Catherine Conconne

Catherine Conconne (born 18 May 1963) is a politician from Martinique. She was elected to the French Senate to represent Martinique in the 2017 French Senate election

Senatorial elections have been held on 24 September 2017 to renew 170 of 3 ...

) since 24 September 2017.

Martinique is also represented in the Economic, Social and Environmental Council by Pierre Marie-Joseph since 26 April 2021

Institutional and statutory evolution of the island

During the 2000s, the political debate in Martinique focused on the question of the evolution of the island's status.assimilationism

Cultural assimilation is the process in which a minority group or culture comes to resemble a society's majority group or assume the values, behaviors, and beliefs of another group whether fully or partially.

The different types of cultural assi ...

and autonomism

Autonomism, also known as autonomist Marxism is an anti-capitalist left-wing political and social movement and theory. As a theoretical system, it first emerged in Italy in the 1960s from workerism (). Later, post-Marxist and anarchist tendenc ...

, clashed. On the one hand, there are those who want a change of status based on Article 73 of the French Constitution, i.e., that all French laws apply in Martinique as of right, which in law is called legislative identity, and on the other hand, the autonomists who want a change of status based on Article 74 of the French Constitution, i.e., an autonomous status subject to the regime of legislative specialty following the example of St. Martin and St. Barthelemy

ST, St, or St. may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Stanza, in poetry

* Suicidal Tendencies, an American heavy metal/hardcore punk band

* Star Trek, a science-fiction media franchise

* Summa Theologica, a compendium of Catholic philosophy an ...

.

Since the constitutional revision of 28 March 2003, Martinique has four options:

* First possibility: the status quo, Martinique retains its status as an Overseas Department and Region, under Article 73 of the Constitution. The DROMs are under the regime of legislative identity. In this framework, the laws and regulations are applicable as of right, with the adaptations required by the particular characteristics and constraints of the communities concerned.

*  Second possibility: if the local stakeholders, and first and foremost the elected representatives, agree, they can, within the framework of Article 73 of the Constitution,

Second possibility: if the local stakeholders, and first and foremost the elected representatives, agree, they can, within the framework of Article 73 of the Constitution,overseas departments

The overseas departments and regions of France (french: départements et régions d'outre-mer, ; ''DROM'') are departments of France that are outside metropolitan France, the European part of France. They have exactly the same status as mainlan ...

, the overseas collectivities are subject to legislative specialization. However, the

However, the French Constitution

The current Constitution of France was adopted on 4 October 1958. It is typically called the Constitution of the Fifth Republic , and it replaced the Constitution of the Fourth Republic of 1946 with the exception of the preamble per a Constitu ...

specifies in Article 72-4Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

) by 50.48% in a referendum held on 7 December 2003.

On 10 January 2010, a consultation

Consultation may refer to:

* Public consultation, a process by which the public's input on matters affecting them is sought

* Consultation (Texas), the 1835 Texas meeting of colonists on a proposed rebellion against the Republic of Mexico

* Consul ...

of the population was held. Voters were asked to vote in a referendum on a possible change in the status of their territory. The ballot proposed voters to "approve or reject the transition to the regime provided for in Article 74 of the Constitution". The majority of voters, 79.3%, said "no".assembly

Assembly may refer to:

Organisations and meetings

* Deliberative assembly, a gathering of members who use parliamentary procedure for making decisions

* General assembly, an official meeting of the members of an organization or of their representa ...

that would exercise the powers of the General Council and the Regional Council.

New collectivity of Martinique

The project of the elected representatives of Martinique to the government proposes a single territorial communityproportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to a type of electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to geographical (e.g. states, regions) and political divis ...

system (the electoral district

An electoral district, also known as an election district, legislative district, voting district, constituency, riding, ward, division, or (election) precinct is a subdivision of a larger state (a country, administrative region, or other polity ...

is divided into four sections). A majority bonus of 20% is granted to the first place list.

The executive body

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems ba ...

of this community is called the "executive council", The new collectivity of Martinique combines the powers of the general and regional councils, but may obtain new powers through empowerments under Article 73. The executive council is assisted by an advisory council, the Economic, Social,

The new collectivity of Martinique combines the powers of the general and regional councils, but may obtain new powers through empowerments under Article 73. The executive council is assisted by an advisory council, the Economic, Social, Environmental

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

, Cultural and Educational Council of Martinique.French Government

The Government of France ( French: ''Gouvernement français''), officially the Government of the French Republic (''Gouvernement de la République française'' ), exercises executive power in France. It is composed of the Prime Minister, who ...

. The ordinary law was submitted to Parliament during the first half of 2011 and resulted in the adoption of Law No. 2011-884 27 July 2011, on the territorial communities of French Guiana and Martinique.

Political forces

Political life in Martinique is essentially based on Martinican political parties and local federations of national parties (PS and LR). The following classification takes into account their position with regard to the statutory evolution of the island: there are the assimilationists (in favor of an institutional or statutory evolution within the framework of Article 73 of the French Constitution), the autonomists

The Autonomists (french: Autonomistes; it, Autonomisti) was a Christian-democratic Italian political party active in the Aosta Valley.

It was founded in 1997 by the union of the regional Italian People's Party with For Aosta Valley, and some f ...

and the independentists (in favor of a statutory evolution based on Article 74 of the French Constitution).

Indeed, on 18 December 2008, during the congress of Martinique's departmental and regional elected representatives, the thirty-three pro-independence elected representatives (MIM/CNCP/MODEMAS/PALIMA) of the two assemblies voted unanimously in favor of a change in the island's status based on Article 74 of the French Constitution, which allows access to autonomy; this change in status was massively rejected (79.3%) by the population during the referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

of 10 January 2010.

Defence

The defence of the department is the responsibility of the French Armed Forces

The French Armed Forces (french: Forces armées françaises) encompass the Army, the Navy, the Air and Space Force and the Gendarmerie of the French Republic. The President of France heads the armed forces as Chief of the Armed Forces.

Franc ...

. Some 1,400 military personnel are deployed in Martinique and Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

– centred on the 33e régiment d'infanterie de Marine in Martinique and incorporating a reserve company of the regiment located in Guadeloupe.

Four French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

vessels are based in Martinique, including: the surveillance frigates and , the patrol and support ship ''Dumont d'Urville'' and the ''Combattante''. The naval aviation element includes Eurocopter AS565 Panther

The Eurocopter (now Airbus Helicopters) AS565 Panther is the military version of the Eurocopter AS365 Dauphin medium-weight multi-purpose twin-engine helicopter. The Panther is used for a wide range of military roles, including combat assault, f ...

or Eurocopter AS365 Dauphin

The Eurocopter (now Airbus Helicopters) AS365 Dauphin (''Dolphin''), also formerly known as the Aérospatiale SA 365 Dauphin 2, is a medium-weight multipurpose twin-engine helicopter produced by Airbus Helicopters. It was originally developed ...

helicopters able to embark on the ''Floréal''-class frigates as required. One ''Engins de Débarquement Amphibie – Standards'' (EDA-S) landing craft is to be delivered to naval forces based in Martinique by 2025. The landing craft is to better support operations in the territory and region.

About 700 National Gendarmerie

The National Gendarmerie (french: Gendarmerie nationale, ) is one of two national law enforcement forces of France, along with the National Police. The Gendarmerie is a branch of the French Armed Forces placed under the jurisdiction of the Minis ...

are also stationed in Martinique while the Maritime Gendarmerie

The Maritime Gendarmerie (french: Gendarmerie maritime) is a component of the French National Gendarmerie under operational control of the chief of staff of the French Navy. It employs 1,157 personnel and operates around thirty patrol boats and h ...

deploys the coastal harbor tug (RPC) Maïtos in the territory.

Geography

Part of the

Part of the archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

of the Antilles

The Antilles (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Antiy; es, Antillas; french: Antilles; nl, Antillen; ht, Antiy; pap, Antias; Jamaican Patois: ''Antiliiz'') is an archipelago bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the south and west, the Gulf of Mex ...

, Martinique is located in the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

about northeast of the coast of South America and about southeast of the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

. It is north of St. Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerin ...

, northwest of Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estimate). ...

and south of Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographically ...

.

The total area of Martinique is , of which is water and the rest land.Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

and Guadeloupe. It stretches in length and in width. The highest point is the volcano of Mount Pelée

Mount Pelée or Mont Pelée ( ; french: Montagne Pelée, ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Montann Pèlé, meaning "bald mountain" or "peeled mountain") is an active volcano at the northern end of Martinique, an island and French overseas departm ...

at above sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as ''orthometric heights''.

The comb ...

. There are numerous small islands

Small may refer to:

Science and technology

* SMALL, an ALGOL-like programming language

* Small (anatomy), the lumbar region of the back

* ''Small'' (journal), a nano-science publication

* <small>, an HTML element that defines smaller text

...

, particularly off the east coast. The Atlantic, or "windward" coast of Martinique is difficult to navigate by ship. A combination of coastal cliffs, shallow coral reefs and cays, and strong winds make the area notoriously hazardous for sea traffic. The

The Atlantic, or "windward" coast of Martinique is difficult to navigate by ship. A combination of coastal cliffs, shallow coral reefs and cays, and strong winds make the area notoriously hazardous for sea traffic. The Caravelle peninsula Caravelle may be a reference to:

* Caravelle, the French marketing name for the typeface Folio

* The Caravelle peninsula of the French Caribbean island of Martinique

* Sud Aviation Caravelle, the short/medium-range jet airliner, produced by Sud Av ...

clearly separates the north Atlantic and south Atlantic coast.

The Caribbean, or "leeward" coast of Martinique is much more favourable to sea traffic. Besides being shielded from the harsh Atlantic trade winds by the island, the sea bed itself descends steeply from the shore. This ensures that most potential hazards are deep underwater, and prevents the growth of corals.

The north of the island is especially mountainous. It features four ensembles of ''pitons'' (

The north of the island is especially mountainous. It features four ensembles of ''pitons'' (volcano

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates are ...

es) and ''mornes'' (mountains): the Piton Conil on the extreme North, which dominates the Dominica Channel

Martinique Passage (also called Dominica Channel) is a strait in the Caribbean that separates Dominica and Martinique. ; Mont Pelée, an active volcano; the Morne Jacob; and the Pitons du Carbet

The Carbet Mountains (, or ''Carbet Nails'') are a massif of volcanic origin on the Caribbean island of Martinique.

The mountain range is a popular tourist, hiking, and rock climbing destination.

Geography

The scenic Carbet Pitons range occup ...

, an ensemble of five extinct volcanoes covered with rainforest and dominating the Bay of Fort de France at . Mont Pelée's volcanic ash

Volcanic ash consists of fragments of rock, mineral crystals, and volcanic glass, created during volcano, volcanic eruptions and measuring less than 2 mm (0.079 inches) in diameter. The term volcanic ash is also often loosely used t ...

has created grey and black sand beaches in the north (in particular between Anse Ceron and Anse des Gallets), contrasting markedly from the white sands of Les Salines in the south.

The south is more easily traversed, though it still features impressive geographic features. Because it is easier to travel to, and due to the many beaches and food facilities throughout this region, the south receives most of the tourism. The beaches from Pointe de Bout, through Diamant (which features right off the coast of Roche de Diamant), St. Luce, the department of St. Anne and down to Les Salines are popular.

The south is more easily traversed, though it still features impressive geographic features. Because it is easier to travel to, and due to the many beaches and food facilities throughout this region, the south receives most of the tourism. The beaches from Pointe de Bout, through Diamant (which features right off the coast of Roche de Diamant), St. Luce, the department of St. Anne and down to Les Salines are popular.

Relief

The terrain is mountainous on this island of volcanic origin. The oldest areas correspond to the volcanic zones at the southern end of the island and towards the peninsula of La Caravelle to the east. The island developed over the last 20 million years according to a sequence of movements and volcanic eruptions to the north.

The volcanic activity is due to the subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

fault located here, where the South American Plate

The South American Plate is a major tectonic plate which includes the continent of South America as well as a sizable region of the Atlantic Ocean seabed extending eastward to the African Plate, with which it forms the southern part of the Mid-A ...

slides beneath the Caribbean Plate

The Caribbean Plate is a mostly oceanic tectonic plate underlying Central America and the Caribbean Sea off the north coast of South America.

Roughly 3.2 million square kilometers (1.2 million square miles) in area, the Caribbean Plate borders ...

. Martinique has eight centres of volcanic activity. The oldest rocks are andesitic

Andesite () is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predomina ...

lavas dated to about 24 million years ago, mixed with tholeiitic

The tholeiitic magma series is one of two main magma series in subalkaline igneous rocks, the other being the calc-alkaline series. A magma series is a chemically distinct range of magma compositions that describes the evolution of a mafic magma i ...

magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

containing iron and magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element with the symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 of the periodic ta ...

. Mount Pelée, the island's most dramatic feature, formed about 400,000 years ago.Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

"''cabesterre''". This term in Martinique designates more specifically the area of La Caravelle. This windward coast, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean, is directly exposed to the trade winds and the sea bottom. The northern part of the Grand River in Sainte-Marie is basically surrounded by cliffs, with very few mooring points; access to maritime navigation is limited to inshore fishing with small traditional Martinique boats.

Flora and fauna

The northern end of the island catches most of the rainfall and is heavily forested, featuring species such as

The northern end of the island catches most of the rainfall and is heavily forested, featuring species such as bamboo

Bamboos are a diverse group of evergreen perennial flowering plants making up the subfamily Bambusoideae of the grass family Poaceae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. The origin of the word "bamboo" is uncertain, bu ...

, mahogany

Mahogany is a straight-grained, reddish-brown timber of three tropical hardwood species of the genus ''Swietenia'', indigenous to the AmericasBridgewater, Samuel (2012). ''A Natural History of Belize: Inside the Maya Forest''. Austin: Unive ...

, rosewood

Rosewood refers to any of a number of richly hued timbers, often brownish with darker veining, but found in many different hues.

True rosewoods

All genuine rosewoods belong to the genus ''Dalbergia''. The pre-eminent rosewood appreciated in ...

and West Indian locust. The south is drier and dominated by savanna-like brush, including cacti

A cactus (, or less commonly, cactus) is a member of the plant family Cactaceae, a family comprising about 127 genera with some 1750 known species of the order Caryophyllales. The word ''cactus'' derives, through Latin, from the Ancient Greek ...

, Copaiba balsam, logwood

''Haematoxylum campechianum'' (blackwood, bloodwood tree, bluewood, campeachy tree, campeachy wood, campeche logwood, campeche wood, Jamaica wood, logwood or logwood tree) is a species of flowering tree in the legume family, Fabaceae, that is na ...

and acacia

''Acacia'', commonly known as the wattles or acacias, is a large genus of shrubs and trees in the subfamily Mimosoideae of the pea family Fabaceae. Initially, it comprised a group of plant species native to Africa and Australasia. The genus na ...

.

Anole

Dactyloidae are a family of lizards commonly known as anoles () and native to warmer parts of the Americas, ranging from southeastern United States to Paraguay. Instead of treating it as a family, some authorities prefer to treat it as a subfami ...

lizards and fer-de-lance snakes are native to the island. Mongoose

A mongoose is a small terrestrial carnivorous mammal belonging to the family Herpestidae. This family is currently split into two subfamilies, the Herpestinae and the Mungotinae. The Herpestinae comprises 23 living species that are native to so ...

s ('' Urva auropunctata''), introduced in the 1800s to control the snake population, have become a particularly cumbersome introduced species

An introduced species, alien species, exotic species, adventive species, immigrant species, foreign species, non-indigenous species, or non-native species is a species living outside its native distributional range, but which has arrived there ...

as they prey upon bird eggs and have exterminated or endangered a number of native birds, including the Martinique trembler

The grey trembler (''Cinclocerthia gutturalis'') is a songbird species in the family (biology), family Mimidae, the mockingbirds and thrashers. It is found only on Martinique and Saint Lucia in the Lesser Antilles of the Caribbean Sea.

Taxono ...

, white-breasted trembler and White-breasted Thrasher

The white-breasted thrasher (''Ramphocinclus brachyurus''), also known as goj blan in Creole, is a species of bird in the family Mimidae. Semper and Sclater (1872) describe the white-breasted thrasher as an "inquisitive and noisy bird" that woul ...

.Jamaican fruit bat

The Jamaican, common or Mexican fruit bat (''Artibeus jamaicensis'') is a fruit-eating bat native to Mexico, through Central America to northwestern South America, as well as the Greater and many of the Lesser Antilles. It is also an uncommon res ...

, the Antillean fruit-eating bat

The Antillean fruit-eating bat (''Brachyphylla cavernarum'') is one of two leaf-nosed bat species belonging to the genus ''Brachyphylla''. The species occurs in the Caribbean from Puerto Rico to St. Vincent and Barbados. Fossil specimens have als ...

, the Little yellow-shouldered bat

The little yellow-shouldered bat (''Sturnira lilium'') is a bat species from South and Central America. It is a frugivore

A frugivore is an animal that thrives mostly on raw fruits or succulent fruit-like produce of plants such as roots, shoo ...

, Davy's naked-backed bat

Davy's (lesser) naked-backed bat (''Pteronotus davyi'') is a small, insect-eating, cave-dwelling bat of the Family Mormoopidae. It is found throughout South and Central America, including Trinidad, but not Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, or French Gui ...

, the Greater bulldog bat

The greater bulldog bat or fisherman bat (''Noctilio leporinus'') is a species of fishing bat native to Latin America (Spanish: ''murciélago pescador''; Portuguese: ''morcego-pescador''). The bat uses echolocation to detect water ripples made ...

, Schwartz's myotis

Schwartz's myotis (''Myotis martiniquensis'') is a species of vesper bat. It is found in Barbados and Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region a ...

, and the Mexican free-tailed bat

The Mexican free-tailed bat or Brazilian free-tailed bat (''Tadarida brasiliensis'') is a medium-sized bat native to the Americas, so named because its tail can be almost half its total length and is not attached to its uropatagium. It has been ...

.

Beaches

Martinique has many beaches:

Hydrography

Due to the island's geographic and morphological characteristics, it has short and torrential rivers. The Lézarde, 30 km long, is the longest on the island.

Major urban areas

The most populous urban unit

In France, an urban unit (''fr: "unité urbaine"'') is a statistical area defined by INSEE, the French national statistics office, for the measurement of contiguously built-up areas. According to the INSEE definition , an "unité urbaine" is a ...

is Le Robert

Le Robert (; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Wobè) is a town and the third-largest commune in the French overseas department of Martinique. It is located in the northeastern (Atlantic) side of the island of Martinique. It contains the Sainte Ros ...

, which covers 11 communes in the southeastern part of the department. The three largest urban units are:

Economy

In 2014, Martinique had a total GDP of 8.4 billion

In 2014, Martinique had a total GDP of 8.4 billion euro

The euro ( symbol: €; code: EUR) is the official currency of 19 out of the member states of the European Union (EU). This group of states is known as the eurozone or, officially, the euro area, and includes about 340 million citizens . ...

s. Its economy is heavily dependent on tourism, limited agricultural production, and grant aid from mainland France.rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is usually aged in oak barrels. Rum is produced in nearly every sugar-producing region of the world, such as the Phili ...

.Chlordecone

Chlordecone, better known in the United States under the brand name Kepone, is an organochlorine compound and a colourless solid. It is an obsolete insecticide, now prohibited in the western world, but only after many thousands of tonnes had bee ...

, a pesticide used in the cultivation of bananas before a ban in 1993, has been found to have contaminated farming ground, rivers and fish, and affected the health of islanders. Fishing and agriculture has had to stop in affected areas, having a significant effect on the economy. The bulk of meat, vegetable and grain requirements must be imported. This contributes to a chronic trade deficit that requires large annual transfers of aid from mainland France.value added tax

A value-added tax (VAT), known in some countries as a goods and services tax (GST), is a type of tax that is assessed incrementally. It is levied on the price of a product or service at each stage of production, distribution, or sale to the end ...

of 2.2–8.5%.

Exports and imports

Exports of goods and services in 2015 amounted to €1,102 million (€504 million of goods), of which more than 20% were refined petroleum products (SARA refinery located in the town of Le Lamentin), €95.9 million of agricultural, forestry, fish and aquaculture products, €62.4 million of agri-food industry products and €54.8 million of other goods.

Imports of goods and services in 2015 were €3,038 million (of which €2,709 million were goods), of which approximately 40% were crude and refined petroleum products, €462.6 million were agricultural and agri-food products, and €442.8 million were mechanical, electrical, electronic and computer equipment.

Tourism

Tourism has become more important than agricultural exports as a source of foreign exchange.

Tourism has become more important than agricultural exports as a source of foreign exchange.

Agriculture

Banana

Banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", distinguis ...

cultivation is the main agricultural activity, with more than 7,200 hectares cultivated, nearly 220,000 tons produced and almost 12,000 jobs (direct + indirect) in 2006 figures. Its weight in the island's economy is low (1.6%), however it generates more than 40% of the agricultural value added.

Rum

Rum

Rum is a liquor made by fermenting and then distilling sugarcane molasses or sugarcane juice. The distillate, a clear liquid, is usually aged in oak barrels. Rum is produced in nearly every sugar-producing region of the world, such as the Phili ...

, and particularly agricultural rum, accounted for 23% of agri-food value added in 2005 and employed 380 people on the island (including traditional rum). The island's production is about 90,000 hl of pure alcohol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl group linked to a hyd ...

in 2009, of which 79,116 hl of pure alcohol is agricultural rum (2009).

Sugarcane

In 2009, sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with ...

cultivation occupied 4,150 hectares, or 13.7% of agricultural land. The area under cultivation has increased by more than 20% in the last 20 years, a rapid increase explained by the high added value of the rum produced and the rise in world sugar prices. This production is increasingly concentrated, with farms of more than 50 hectares accounting for 6.2% of the farms and 73.4% of the area under production. Annual production was about 220,000 tons in 2009, of which almost 90,000 tons went to sugar production, and the rest was delivered to agricultural rum distilleries.

Pineapples

Pineapple

The pineapple (''Ananas comosus'') is a tropical plant with an edible fruit; it is the most economically significant plant in the family Bromeliaceae. The pineapple is indigenous to South America, where it has been cultivated for many centuri ...

s used to be an important part of agricultural production, but in 2005, according to IEDOM, they accounted for only 1% of agricultural production in value (2.5 million euros compared to 7.9 million in 2000).

Infrastructure

Transport

Martinique's main and only airport with commercial flights is Martinique Aimé Césaire International Airport

Martinique Aimé Césaire International Airport (french: link=no, Aéroport international de Martinique-Aimé-Césaire, ) is the international airport of Martinique in the French West Indies. Located in Le Lamentin, a suburb of the capital Fort ...

. It serves flights to and from Europe, the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

, Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

, the United States, and Canada.List of airports in Martinique

This is a list of airports in Martinique, sorted by location.

Martinique is an island in the eastern Caribbean. It is an overseas department (french: département d'outre-mer, ''DOM'') of France.

ICAO location identifiers are linked to each air ...

.

Fort-de-France is the major harbour. The island has regular ferry service to Guadeloupe, Dominica and St. Lucia.

Roads

In 2019, Martinique's road network consisted of 2,123 km:

* 7 km of highway (A1 between Fort-de-France

Fort-de-France (, , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Fodfwans) is a Communes of France, commune and the capital city of Martinique, an overseas department and region of France located in the Caribbean. It is also one of the major cities in the ...

and Le Lamentin) ;

* 919 km of departmental and national roads

*  1,197 km of communal roads.

In proportion to its population, Martinique is the French department with the highest number of vehicle registrations.

1,197 km of communal roads.

In proportion to its population, Martinique is the French department with the highest number of vehicle registrations.inhabitants

Domicile is relevant to an individual's "personal law," which includes the law that governs a person's status and their property. It is independent of a person's nationality. Although a domicile may change from time to time, a person has only one ...

(+14 in 5 years), to the great benefit of dealers.

Public transport

The public

In public relations and communication science, publics are groups of individual people, and the public (a.k.a. the general public) is the totality of such groupings. This is a different concept to the sociological concept of the ''Öffentlichkei ...

entity "Martinique Transport" was created in December 2014. This establishment is in charge of urban, intercity passenger (cabs), maritime, school and disabled student transport throughout the island, as well as the bus network.

Ports

Given the insular nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

of Martinique, its supply by sea is important. The port of Fort-de-France is the seventh largest French port in terms of container traffic.

Air services

The island's airport is Martinique Aimé Césaire International Airport

Martinique Aimé Césaire International Airport (french: link=no, Aéroport international de Martinique-Aimé-Césaire, ) is the international airport of Martinique in the French West Indies. Located in Le Lamentin, a suburb of the capital Fort ...

. It is located in the municipality of Le Lamentin. Its civilian traffic (1,696,071 passengers in 2015) ranks it thirteenth among French airports, behind those of two other overseas departments (Guadeloupe – Pôle Caraïbes de Pointe-à-Pitre Airport, Guadeloupe, and La Réunion-Roland-Garros Airport). Its traffic is very strongly polarized by metropolitan France

Metropolitan France (french: France métropolitaine or ''la Métropole''), also known as European France (french: Territoire européen de la France) is the area of France which is geographically in Europe. This collective name for the European ...

, with very limited (192,244 passengers in 2017) and declining international traffic.

Railroads

At the beginning of the 20th century, Martinique had more than 240 km of railways serving the sugar factories (cane transport). Only one tourist train remains in Sainte-Marie between the Saint-James house and the banana museum.

Communications

The country code top-level domain

A country code top-level domain (ccTLD) is an Internet top-level domain generally used or reserved for a country, sovereign state, or dependent territory identified with a country code. All ASCII ccTLD identifiers are two letters long, and all t ...

for Martinique is .mq

.mq is the Internet country code top-level domain (ccTLD) for Martinique.

The .mq top-level domain was managed by SYSTEL until SYSTEL was bought by Mediaserv. The registration services were later reopened, with the country code's current techni ...

, but .fr

.fr is the Internet country code top-level domain (ccTLD) in the Domain Name System of the Internet for France. It is administered by AFNIC. The domain includes all individuals and organizations registered at the Association française pour le ...

is often used instead. The country code for international dialling is 596. The entire island uses a single area code (also 596) for landline phones and 696 for cell phones. (596 is dialled twice when calling a Martinique landline from another country.)

Mobile telephony

There are three mobile telephone networks in Martinique: Orange, SFR Caraïbe and Digicel. The arrival of Free, in partnership with Digicel, was planned for 2020.45

According to Arcep, by mid-2018, Martinique is 99% covered by 4G.

Television

The DTT package includes 10 free channels: 4 national channels of the France Télévisions group, the news channel France 24

France 24 ( in French) is a French state-owned international news television network based in Paris. Its channels broadcast in French, English, Arabic, and Spanish and are aimed at the overseas market.

Based in the Paris suburb of Issy-les-M ...

, Arte and 4 local channels Martinique 1re, ViàATV, KMT Télévision. Zouk TV stopped broadcasting in April 2021 and will be subsequently replaced by Zitata TV, whose broadcasting is delayed following the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic, also known as the coronavirus pandemic, is an ongoing global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The novel virus was first identif ...

.