Martin Niemöller on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Friedrich Gustav Emil Martin Niemöller (; 14 January 18926 March 1984) was a German

„…habe ich geschwiegen“. Zur Frage eines Antisemitismus bei Martin Niemöller

' ''tr. "...I kept quiet ”. On the question of anti-Semitism with Martin Niemöller"'' For his opposition to the Nazis' state control of the churches, Niemöller was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps from 1938 to 1945. He narrowly escaped execution. After his imprisonment, he expressed his deep regret about not having done enough to help victims of the Nazis. He turned away from his earlier nationalistic beliefs and was one of the initiators of the ''

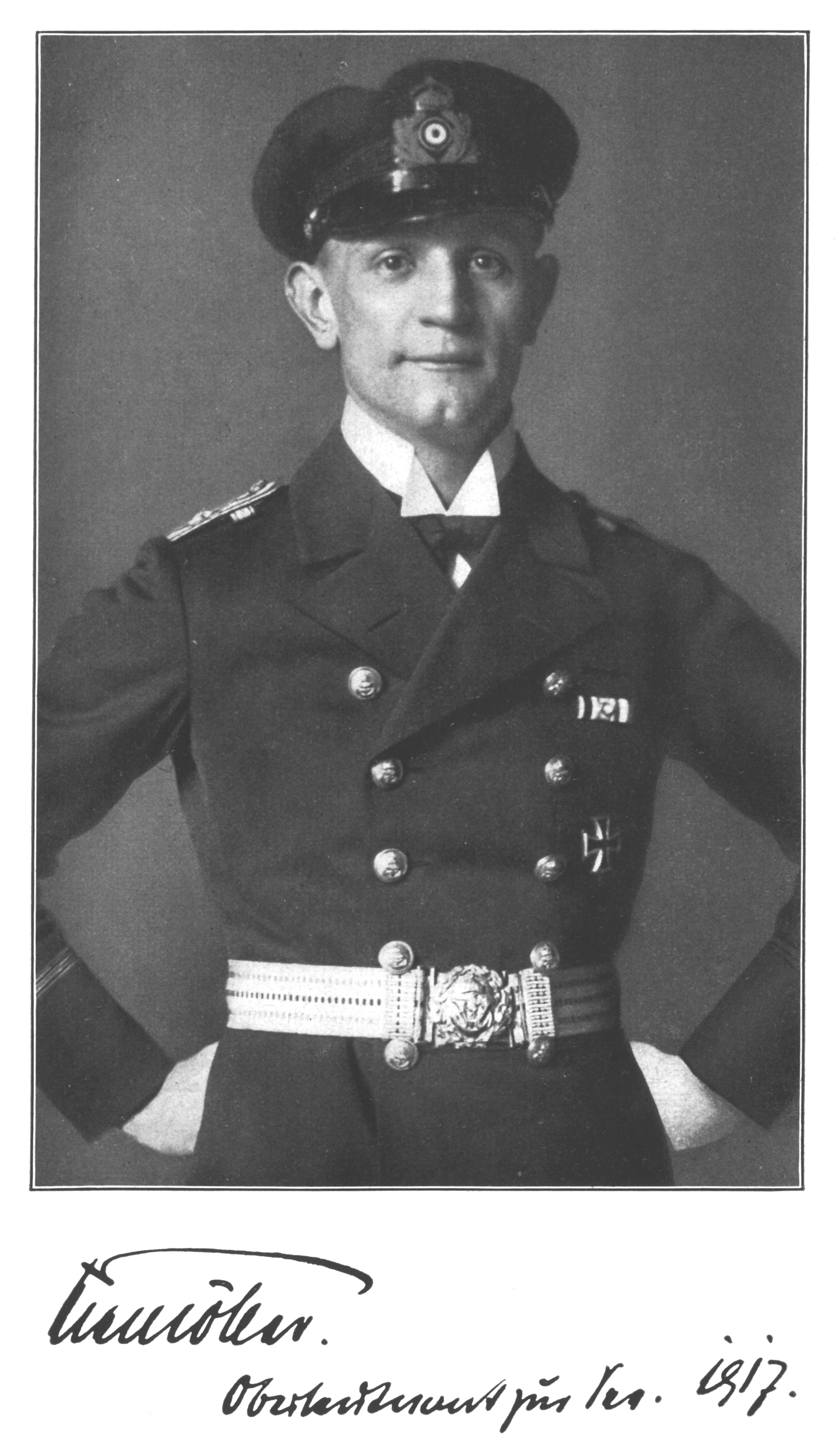

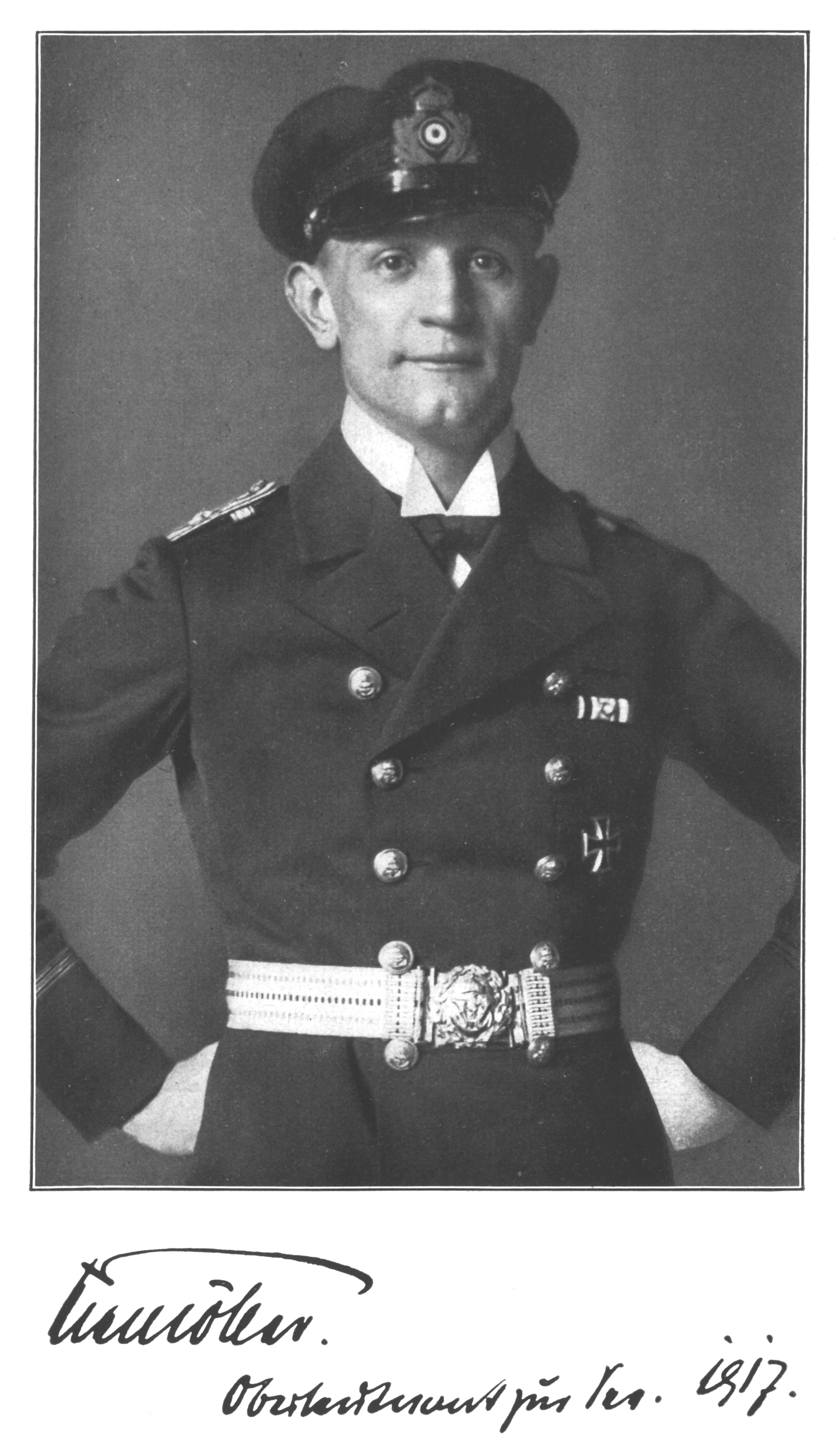

In January 1917, Niemöller was

In January 1917, Niemöller was

''Die Bekennende Kirche und die Gründung der Evangelischen Kirche in Hessen und Nassau, EKHN.''

Diss. Justus Liebig Universität Gießen. * Bentley, James (1984) ''Martin Niemoeller'', New York: The Free Press. . ** German: (1985) ''Martin Niemöller. Eine Biographie''. Munchen: Beck. . * * * Schreiber, Matthias (2008) ''Martin Niemöller.'' 2. Auflage. Reinbek: Rowohlt. . * Wette, Wolfram (2010) ''Seiner Zeit voraus. Martin Niemöllers Friedensinitiativen (1945–1955)''. In: Detlef Bald (Hrsg.): ''Friedensinitiativen in der Frühzeit des Kalten Krieges 1945–1955'' (= Frieden und Krieg, 17). Essen. S. 227–241.

"Yellow Triangle"

a song written about him by Irish singer-songwriter

Who Was Martin Niemoller?

Harold Marcuse, UC Santa Barbara (2005) * ttp://isurvived.org/home.html#Prologue Niemöller's famous quotation as posted by Holocaust Survivors' Network

A biography of Niemöller

* ttp://www.buzzle.com/editorials/7-10-2006-101772.asp Pastor Martin Niemöller Sonal Panse * {{DEFAULTSORT:Niemoller, Martin 1892 births 1984 deaths People from Lippstadt People from the Province of Westphalia 20th-century German Lutheran clergy German Lutheran theologians 20th-century German Protestant theologians German Peace Society members Christian Peace Conference members Anti–Vietnam War activists German anti-war activists German Christian pacifists Lutheran pacifists German poets German people of World War II Dachau concentration camp survivors U-boat commanders (Imperial German Navy) Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 1st class Lenin Peace Prize recipients Imperial German Navy personnel of World War I Protestants in the German Resistance 20th-century Freikorps personnel Sachsenhausen concentration camp survivors Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany German male poets

theologian

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

pastor. He is best known for his opposition to the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

regime during the late 1930s and for his widely quoted 1946 poem " First they came ...". The poem exists in many versions; the one featured on the United States Holocaust Memorial

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) is the United States' official memorial to the Holocaust. Adjacent to the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the USHMM provides for the documentation, study, and interpretation of Holocaust his ...

reads: "First they came for the Communists, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a communist. Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—Because I was not a Jew. Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me."

Niemöller was a national conservative

National conservatism is a nationalist variant of conservatism that concentrates on upholding national and cultural identity. National conservatives usually combine nationalism with conservative stances promoting traditional cultural values, f ...

and initially a supporter of Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and a self-identified antisemite,Michael, Robert. Theological Myth, German Antisemitism, and the Holocaust: The Case of Martin Niemoeller, Holocaust and Genocide Studies.1987; 2: 105–122. but he became one of the founders of the Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German ...

, which opposed the Nazification of German Protestant churches. He opposed the Nazis' Aryan Paragraph

An Aryan paragraph (german: Arierparagraph) was a clause in the statutes of an organization, corporation, or real estate deed that reserved membership and/or right of residence solely for members of the "Aryan race" and excluded from such rights a ...

.Martin Stöhr, „…habe ich geschwiegen“. Zur Frage eines Antisemitismus bei Martin Niemöller

' ''tr. "...I kept quiet ”. On the question of anti-Semitism with Martin Niemöller"'' For his opposition to the Nazis' state control of the churches, Niemöller was imprisoned in Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps from 1938 to 1945. He narrowly escaped execution. After his imprisonment, he expressed his deep regret about not having done enough to help victims of the Nazis. He turned away from his earlier nationalistic beliefs and was one of the initiators of the ''

Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt

The Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt (german: Stuttgarter Schuldbekenntnis) was a declaration issued on October 19, 1945, by the Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany (', EKD), in which it confessed guilt for its inadequacies in opposition to ...

''. From the 1950s on, he was a vocal pacifist and anti-war activist, and vice-chair of War Resisters' International

War Resisters' International (WRI), headquartered in London, is an international anti-war organisation with members and affiliates in over 30 countries.

History

''War Resisters' International'' was founded in Bilthoven, Netherlands in 1921 unde ...

from 1966 to 1972. He met with Ho Chi Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as (' Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), (' Old father of the people') and by other aliases, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and statesman. He served as P ...

during the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

and was a committed campaigner for nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

.Rupp, Hans Karl. "Niemöller, Martin", in ''The World Encyclopedia of Peace''. Edited by Linus Pauling, Ervin László

Ervin László (; born 12 June 1932) is a Hungarian philosopher of science, systems theorist, integral theorist, originally a classical pianist. He is an advocate of the theory of quantum consciousness.

Early life and education

László wa ...

, and Jong Youl Yoo Jong may refer to:

Surname

*Chung (Korean surname), spelled Jong in North Korea

*Zhong (surname), spelled Jong in the Gwoyeu Romatzyh system

*Common Dutch surname "de Jong"; see

** De Jong

** De Jonge

** De Jongh

* Erica Jong (born 1942), Ameri ...

. Oxford : Pergamon, 1986. , (vol 2, p.45-6).

Youth and World War I participation

Niemöller was born in Lippstadt, then in thePrussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

Province of Westphalia (now in North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia (german: Nordrhein-Westfalen, ; li, Noordrien-Wesfale ; nds, Noordrhien-Westfalen; ksh, Noodrhing-Wäßßfaale), commonly shortened to NRW (), is a state (''Land'') in Western Germany. With more than 18 million inha ...

), on 14 January 1892 to the Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

pastor Heinrich Niemöller and his wife Pauline (née Müller), and grew up in a very conservative home. In 1900, the family moved to Elberfeld

Elberfeld is a municipal subdivision of the German city of Wuppertal; it was an independent town until 1929.

History

The first official mentioning of the geographic area on the banks of today's Wupper River as "''elverfelde''" was in a doc ...

where he finished school, taking his abitur exam in 1908.

He began a career as an officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," f ...

of the Imperial Navy of the German Empire, and in 1915, was assigned to U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s. His first boat was . In October of that year, he joined the submarine mother boat , followed by training on the submarine . In February 1916, he became second officer on , which was assigned to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

in April 1916.''Current Biography 1943'', pg.555 There the submarine fought on the Saloniki front, patrolled in the Strait of Otranto and from December 1916 onward, planted many mines in front of Port Said and was involved in commerce raiding

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than en ...

. Flying a French flag as a ruse of war

The French , sometimes literally translated as ruse of war, is a non-uniform term; generally what is understood by "ruse of war" can be separated into two groups. The first classifies the phrase purely as an act of military deception against one's ...

, the SM ''U-73'' sailed past British warships and torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, s ...

ed two Allied troopships and a British man-of-war.

In January 1917, Niemöller was

In January 1917, Niemöller was navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's primar ...

of . Later he returned to Kiel

Kiel () is the capital and most populous city in the northern German state of Schleswig-Holstein, with a population of 246,243 (2021).

Kiel lies approximately north of Hamburg. Due to its geographic location in the southeast of the Jutland ...

, and in August 1917, he became first officer on , which attacked numerous ships at Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, in the Bay of Biscay, and other places. During this time, the SM ''U-151'' crew set a record by sinking 55,000 tons of Allied ships in 115 days at sea. In June 1918, he became commander of the . Under his command, ''UC-67'' achieved a temporary closing of the French port of Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

by sinking ships in the area, by torpedoes, and by the laying of mines.

For his achievements, Niemöller was awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia es ...

First Class. When the war drew to a close, he decided to become a preacher, a story he later recounted in his book ''Vom U-Boot zur Kanzel'' (''From U-boat to Pulpit''). At war's end, Niemöller resigned his commission, as he rejected the new democratic government of the German Empire that formed after the abdication of the German Emperor Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

.

Weimar Republic and education as pastor

On 20 July 1919, he married Else Bremer (20 July 1890 – 7 August 1961). That same year, he began working at a farm in Wersen nearOsnabrück

Osnabrück (; wep, Ossenbrügge; archaic ''Osnaburg'') is a city in the German state of Lower Saxony. It is situated on the river Hase in a valley penned between the Wiehen Hills and the northern tip of the Teutoburg Forest. With a population ...

but gave up becoming a farmer as he could not afford to buy his own farm. He subsequently pursued his earlier idea of becoming a Lutheran pastor and studied Protestant theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

at the Westphalian Wilhelms-University in Münster

Münster (; nds, Mönster) is an independent city (''Kreisfreie Stadt'') in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It is in the northern part of the state and is considered to be the cultural centre of the Westphalia region. It is also a state di ...

from 1919 to 1923. His motivation was his ambition to give a disordered society meaning and order through the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

and church bodies.

During the Ruhr Uprising in 1920, he was battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions a ...

commander of the "III. Bataillon der Akademischen Wehr Münster" belonging to the paramilitary Freikorps

(, "Free Corps" or "Volunteer Corps") were irregular German and other European military volunteer units, or paramilitary, that existed from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. They effectively fought as mercenary or private armies, rega ...

.

Niemöller was ordained on 29 June 1924. Subsequently, the united

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two f ...

Evangelical Church of the old-Prussian Union

The Prussian Union of Churches (known under multiple other names) was a major Protestant church body which emerged in 1817 from a series of decrees by Frederick William III of Prussia that united both Lutheran and Reformed denominations in Pr ...

appointed him curate of Münster's Church of the Redeemer. After serving as the superintendent of the Inner Mission

The Inner Mission (german: Innere Mission, also translated as Home Mission) was and is a movement of German evangelists, set up by Johann Hinrich Wichern in Wittenberg in 1848 based on a model of Theodor Fliedner. It quickly spread from Germany t ...

in the old-Prussian ecclesiastical province of Westphalia, Niemöller in 1931 became pastor of the Jesus Christus Kirche (comprising a congregation together with St. Anne's Church) in Dahlem, an affluent suburb of Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and List of cities in Germany by population, largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's List of cities in the European Union by population within ci ...

."Niemöller", 8:698.

Role in Nazi Germany

Like most Protestant pastors, Niemöller was a national conservative, and openly supported the conservative opponents of theWeimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is ...

. He thus welcomed Hitler's accession to power in 1933, believing that it would bring a national revival. In his autobiography, ''From U-Boat to Pulpit'' published in the spring of 1933, he called the time of "the System" (a pejorative name for the Weimar Republic) the "years of darkness" and hailed Adolf Hitler for beginning a "national revival". Niemöller's autobiography received positive reviews in Nazi newspapers and was a bestseller. However, he decidedly opposed the Nazis' "Aryan Paragraph

An Aryan paragraph (german: Arierparagraph) was a clause in the statutes of an organization, corporation, or real estate deed that reserved membership and/or right of residence solely for members of the "Aryan race" and excluded from such rights a ...

" to Jewish converts to Lutheranism. In 1936, he signed the petition of a group of Protestant churchmen which sharply criticized Nazi policies and declared the Aryan Paragraph incompatible with the Christian virtue of charity

Charity may refer to:

Giving

* Charitable organization or charity, a non-profit organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being of persons

* Charity (practice), the practice of being benevolent, giving and sharing

* C ...

.

The Nazi regime reacted with mass arrests and charges against almost 800 pastors and ecclesiastical lawyers. In 1933, Niemöller founded the '' Pfarrernotbund'', an organization of pastors to "combat rising discrimination against Christians of Jewish background". By the autumn of 1934, Niemöller joined other Lutheran and Protestant churchmen such as Karl Barth and Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (; 4 February 1906 – 9 April 1945) was a German Lutheran pastor, theologian and anti-Nazi dissident who was a key founding member of the Confessing Church. His writings on Christianity's role in the secular world have ...

in founding the Confessional Church

Confessionalism, in a religious (and particularly Christian) sense, is a belief in the importance of full and unambiguous assent to the whole of a religious teaching. Confessionalists believe that differing interpretations or understandings, espe ...

, a Protestant group that opposed the Nazification of the German Protestant churches

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

. Author and Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

laureate Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novell ...

published Niemöller's sermons in the United States and praised his bravery.

However, Niemöller only gradually abandoned his national conservative views. Even as he opposed the Nazis, he made pejorative remarks about Jews of faith while protecting—in his own church—baptised Christians, persecuted as Jews by the Nazis, due to their forefathers' Jewish descent. In one sermon in 1935, he remarked: "What is the reason for heirobvious punishment, which has lasted for thousands of years? Dear brethren, the reason is easily given: the Jews brought the Christ of God to the cross!"

This has led to controversy about his attitude toward Jews and to accusations of anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

. Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

historian Robert Michael argues that Niemöller's statements were a result of traditional anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, and that Niemöller agreed with the Nazis' position on the "Jewish question" at that time. American sociologist Werner Cohn lived as a Jew in Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, and he also reports on antisemitic statements by Niemöller.

Thus, Niemöller's ambivalent and often contradictory behaviour during the Nazi period makes him a controversial figure among those who opposed the Nazis. Even his motives are disputed. Historian Raimund Lammersdorf considers Niemöller "an opportunist who had no quarrel with Hitler politically and only began to oppose the Nazis when Hitler threatened to attack the churches". Others have disputed this view and emphasize the risks that Niemöller took while opposing the Nazis. Nonetheless, Niemöller's behaviour contrasts sharply with the much more broad-minded attitudes of other Confessing Church

The Confessing Church (german: link=no, Bekennende Kirche, ) was a movement within German Protestantism during Nazi Germany that arose in opposition to government-sponsored efforts to unify all Protestant churches into a single pro-Nazi German ...

activists such as Hermann Maas. Pastor and liberal politician Maas—unlike Niemöller—belonged to those who unequivocally opposed every form of antisemitism and was later accorded the title ''Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sa ...

'' by Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

.

Imprisonment and liberation

Niemöller was arrested on 1 July 1937. On 2 March 1938, he was tried by a "Special Court" for activities against the State. He was given Sonder- und Ehrenhaft status. He received a 2,000 Reichsmark fine and seven-months imprisonment. But as he had been detained pre-trial for longer than the seven-month jail term, he was released by the Court after sentencing. However, he was immediately rearrested byHimmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

's Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one orga ...

—presumably because Rudolf Hess found the sentence too lenient and decided to take "merciless action" against him. He was interned in Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps for "protective custody" from 1938 to 1945.

He volunteered in September 1939 to become a U-boat commander; his offer was rejected.

His former cellmate, Leo Stein, was released from Sachsenhausen to go to America, and he wrote an article about Niemöller for ''The National Jewish Monthly'' in 1941. Stein reports having asked Niemöller why he ever supported the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

, to which Niemöller replied:

In late April 1945, Niemöller—together with about 140 high-ranking prisoners—was transported to the Alpenfestung

The Alpine Fortress (german: Alpenfestung) or Alpine Redoubt was the World War II national redoubt planned by Heinrich Himmler in November and December 1943"Himmler started laying the plans for underground warfare in the last two months of 1943 ...

. The group possibly were to be used as hostages in surrender negotiations. The transport's SS guards had orders to kill everyone if liberation by the advancing Western Allies became imminent. However, in the south Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous area, Autonomous Provinces of Italy, province

, image_skyline = ...

region, regular German troops took the inmates into protective custody. The entire group was eventually liberated by advanced units of the U.S. Seventh Army.

Later life and death

In 1947, Niemöller was denied Nazi victim status. According to Lammersdorf, there had been some attempts to whitewash his past, which were soon followed by harsh criticism because of his role as an NSDAP supporter and his attitude toward Jews. Niemöller himself never denied his own guilt in the time of the Nazi regime. In 1959, he was asked about his former attitude toward Jews by Alfred Wiener, a Jewish researcher into racism and war crimes committed by the Nazi regime. In a letter to Wiener, Niemöller stated that his eight-year imprisonment by the Nazis became the turning point in his life, after which he viewed things differently. Niemöller was president of the Protestant Church in Hesse and Nassau from 1947 to 1961. He was one of the initiators of theStuttgart Declaration of Guilt

The Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt (german: Stuttgarter Schuldbekenntnis) was a declaration issued on October 19, 1945, by the Council of the Evangelical Church in Germany (', EKD), in which it confessed guilt for its inadequacies in opposition to ...

, signed by leading figures in the German Protestant churches. The document acknowledged that the churches had not done enough to resist the Nazis.

Under the impact of a meeting with Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn (; 8 March 1879 – 28 July 1968) was a German chemist who was a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is referred to as the father of nuclear chemistry and father of nuclear fission. Hahn and Lise Meitner ...

(referred to as the "father of nuclear chemistry

Nuclear chemistry is the sub-field of chemistry dealing with radioactivity, nuclear processes, and transformations in the nuclei of atoms, such as nuclear transmutation and nuclear properties.

It is the chemistry of radioactive elements such as ...

") in July 1954, Niemöller became an ardent pacifist and campaigner for nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

. He was soon a leading figure in the post-war German peace movement

A peace movement is a social movement which seeks to achieve ideals, such as the ending of a particular war (or wars) or minimizing inter-human violence in a particular place or situation. They are often linked to the goal of achieving world peac ...

and was even brought to court in 1959 because he had spoken about the military in a very unflattering way. His visit to North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; vi, Việt Nam Dân chủ Cộng hòa), was a socialist state supported by the Soviet Union (USSR) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Southeast Asia that existed f ...

's communist ruler Ho Chi Minh

(: ; born ; 19 May 1890 – 2 September 1969), commonly known as (' Uncle Hồ'), also known as ('President Hồ'), (' Old father of the people') and by other aliases, was a Vietnamese revolutionary and statesman. He served as P ...

at the height of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

caused an uproar. Niemöller also took active part in protests against the Vietnam War and the NATO Double-Track Decision

The NATO Double-Track Decision was the decision by NATO from December 12, 1979 to offer the Warsaw Pact a mutual limitation of medium-range ballistic missiles and intermediate-range ballistic missiles. It was combined with a threat by NATO to d ...

.

In 1961, he became president of the World Council of Churches

The World Council of Churches (WCC) is a worldwide Christian inter-church organization founded in 1948 to work for the cause of ecumenism. Its full members today include the Assyrian Church of the East, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, most ju ...

. He was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize

The International Lenin Peace Prize (russian: международная Ленинская премия мира, ''mezhdunarodnaya Leninskaya premiya mira)'' was a Soviet Union award named in honor of Vladimir Lenin. It was awarded by a pane ...

in December 1966.

He gave a sermon at the 30 April 1967 dedication of a Protestant "Church of Atonement" in the former Dachau concentration camp, which in 1965 had been partially restored as a memorial site.

Niemöller died at Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

, West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

, on 6 March 1984, at the age of 92.

Selected writings

* ''From U-boat to Pulpit'', including an Appendix From Pulpit to Prison by Henry Smith Leiper (Chicago, New York: Willett, Clark, 1937). * ''Here Stand I!'' with foreword by James Moffatt, translated by Jane Lymburn (Chicago, New York: Willett, Clark, 1937). * ''The Gestapo Defied, Being the Last Twenty-eight Sermons by Martin Niemöller'' (London tc. W. Hodge and Company, Limited, 1941). * ''Of Guilt and Hope'', translated by Renee Spodheim (New York: Philosophical Library, 947. * "What is the Church?" ''Princeton Seminary Bulletin'', vol. 40, no. 4 (1947): 10–16. * "The Word of God is Not Bound", ''Princeton Seminary Bulletin'', vol. 41, no. 1 (1947): 18–23. * ''Exile in the Fatherland: Martin Niemöller's Letters from Moabit Prison'', translated by Ernst Kaemke, Kathy Elias, and Jacklyn Wilfred; edited by Hubert G. Locke (Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., c1986). * "Dachau Sermons", Martin Niemöller, translated by Robert H. Pfeiffer, Harvard Divinity School 1947 (published by Latimer House Limited, 33 Ludgate Hill, London EC4)See also

* " First they came ..." *List of peace activists

This list of peace activists includes people who have proactively advocated diplomatic, philosophical, and non-military resolution of major territorial or ideological disputes through nonviolent means and methods. Peace activists usually work ...

* Franz Hildebrandt

Franz Hildebrandt (February 20, 1909, in Berlin – November 25, 1985, in Edinburgh) was a German-born Lutheran, and later Methodist, pastor and theologian, forced into exile during World War II, and subsequently active in the United Kingdom and th ...

* Deutsches Historisches Museum

The German Historical Museum (german: Deutsches Historisches Museum), known by the acronym DHM, is a museum in Berlin, Germany devoted to German history. It describes itself as a place of "enlightenment and understanding of the shared history ...

References

Notes Bibliography * Borchmeyer, Doris (2010''Die Bekennende Kirche und die Gründung der Evangelischen Kirche in Hessen und Nassau, EKHN.''

Diss. Justus Liebig Universität Gießen. * Bentley, James (1984) ''Martin Niemoeller'', New York: The Free Press. . ** German: (1985) ''Martin Niemöller. Eine Biographie''. Munchen: Beck. . * * * Schreiber, Matthias (2008) ''Martin Niemöller.'' 2. Auflage. Reinbek: Rowohlt. . * Wette, Wolfram (2010) ''Seiner Zeit voraus. Martin Niemöllers Friedensinitiativen (1945–1955)''. In: Detlef Bald (Hrsg.): ''Friedensinitiativen in der Frühzeit des Kalten Krieges 1945–1955'' (= Frieden und Krieg, 17). Essen. S. 227–241.

External links

*"Yellow Triangle"

a song written about him by Irish singer-songwriter

Christy Moore

Christopher Andrew "Christy" Moore (born 7 May 1945) is an Irish folk singer, songwriter and guitarist. In addition to his significant success as an individual, he is one of the founding members of Planxty and Moving Hearts. His first album, ...

Who Was Martin Niemoller?

Harold Marcuse, UC Santa Barbara (2005) * ttp://isurvived.org/home.html#Prologue Niemöller's famous quotation as posted by Holocaust Survivors' Network

A biography of Niemöller

* ttp://www.buzzle.com/editorials/7-10-2006-101772.asp Pastor Martin Niemöller Sonal Panse * {{DEFAULTSORT:Niemoller, Martin 1892 births 1984 deaths People from Lippstadt People from the Province of Westphalia 20th-century German Lutheran clergy German Lutheran theologians 20th-century German Protestant theologians German Peace Society members Christian Peace Conference members Anti–Vietnam War activists German anti-war activists German Christian pacifists Lutheran pacifists German poets German people of World War II Dachau concentration camp survivors U-boat commanders (Imperial German Navy) Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914), 1st class Lenin Peace Prize recipients Imperial German Navy personnel of World War I Protestants in the German Resistance 20th-century Freikorps personnel Sachsenhausen concentration camp survivors Grand Crosses 1st class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany German male poets