Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American

Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

minister,

civil rights activist

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

and

political philosopher

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and legitimacy of political institutions, such as states. This field investigates different forms of government, ranging from de ...

who was a leader of the

civil rights movement from 1955 until

his assassination in 1968. He advanced

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

for

people of color

The term "person of color" (: people of color or persons of color; abbreviated POC) is used to describe any person who is not considered "white". In its current meaning, the term originated in, and is associated with, the United States. From th ...

in the United States through the use of

nonviolent resistance

Nonviolent resistance, or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, construct ...

and nonviolent

civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

against

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

and other forms of legalized

discrimination

Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong, such as race, gender, age, class, religion, or sex ...

.

A

Black church

The Black church (sometimes termed Black Christianity or African American Christianity) is the faith and body of Christian denominations and congregations in the United States that predominantly minister to, and are led by, African Americans, ...

leader, King participated in and led marches for the

right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

,

desegregation,

labor rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, the ...

, and other

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

. He oversaw the 1955

Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social boycott, protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United ...

and became the first president of the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African Americans, African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., ...

(SCLC). As president of the SCLC, he led the unsuccessful

Albany Movement

The Albany Movement was a desegregation and voters' rights coalition formed in Albany, Georgia, in November 1961. This movement was founded by local black leaders and ministers, as well as members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Commi ...

in

Albany, Georgia

Albany ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. Located on the Flint River, it is the county seat of Dougherty County, Georgia, Dougherty County, and is the sole incorporated city in that county. Located in Southwest Geo ...

, and helped organize nonviolent 1963 protests in

Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham ( ) is a city in the north central region of Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Jefferson County, Alabama, Jefferson County. The population was 200,733 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List ...

. King was one of the leaders of the 1963

March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (commonly known as the March on Washington or the Great March on Washington) was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

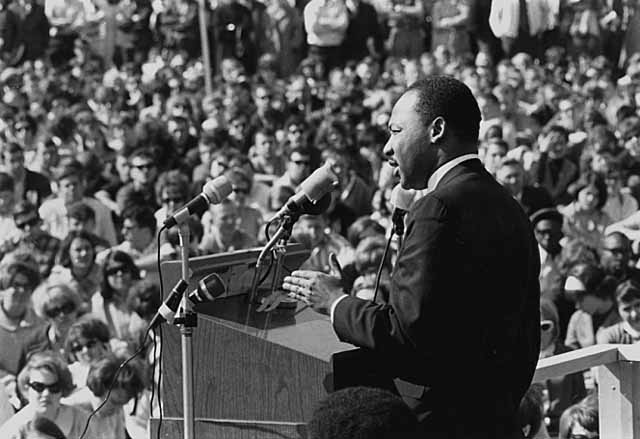

, where he delivered his "

I Have a Dream

"I Have a Dream" is a Public speaking, public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist and Baptist minister Martin Luther King Jr. during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963. In the speech, Kin ...

" speech on the steps of the

Lincoln Memorial

The Lincoln Memorial is a List of national memorials of the United States, U.S. national memorial honoring Abraham Lincoln, the List of presidents of the United States, 16th president of the United States, located on the western end of the Nati ...

, and helped organize two of the three

Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three Demonstration (protest), protest marches, held in 1965, along the highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery. The marches were organized by Nonviolence, nonvi ...

during the 1965 Selma voting rights movement. The civil rights movement achieved pivotal legislative gains in the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

, the

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights move ...

, and the

Fair Housing Act of 1968. There were dramatic standoffs with

segregationist

Racial segregation is the separation of people into racial or other ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, such as schools and hospitals by peopl ...

authorities, who often responded violently.

King was jailed several times.

Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

(FBI) director

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

considered King a radical and made him an object of

COINTELPRO

COINTELPRO (a syllabic abbreviation derived from Counter Intelligence Program) was a series of covert and illegal projects conducted between 1956 and 1971 by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltr ...

from 1963. FBI agents investigated him for possible communist ties, spied on his personal life, and secretly recorded him. In 1964, the FBI mailed King

a threatening anonymous letter, which he interpreted as an attempt to make him commit

suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

.

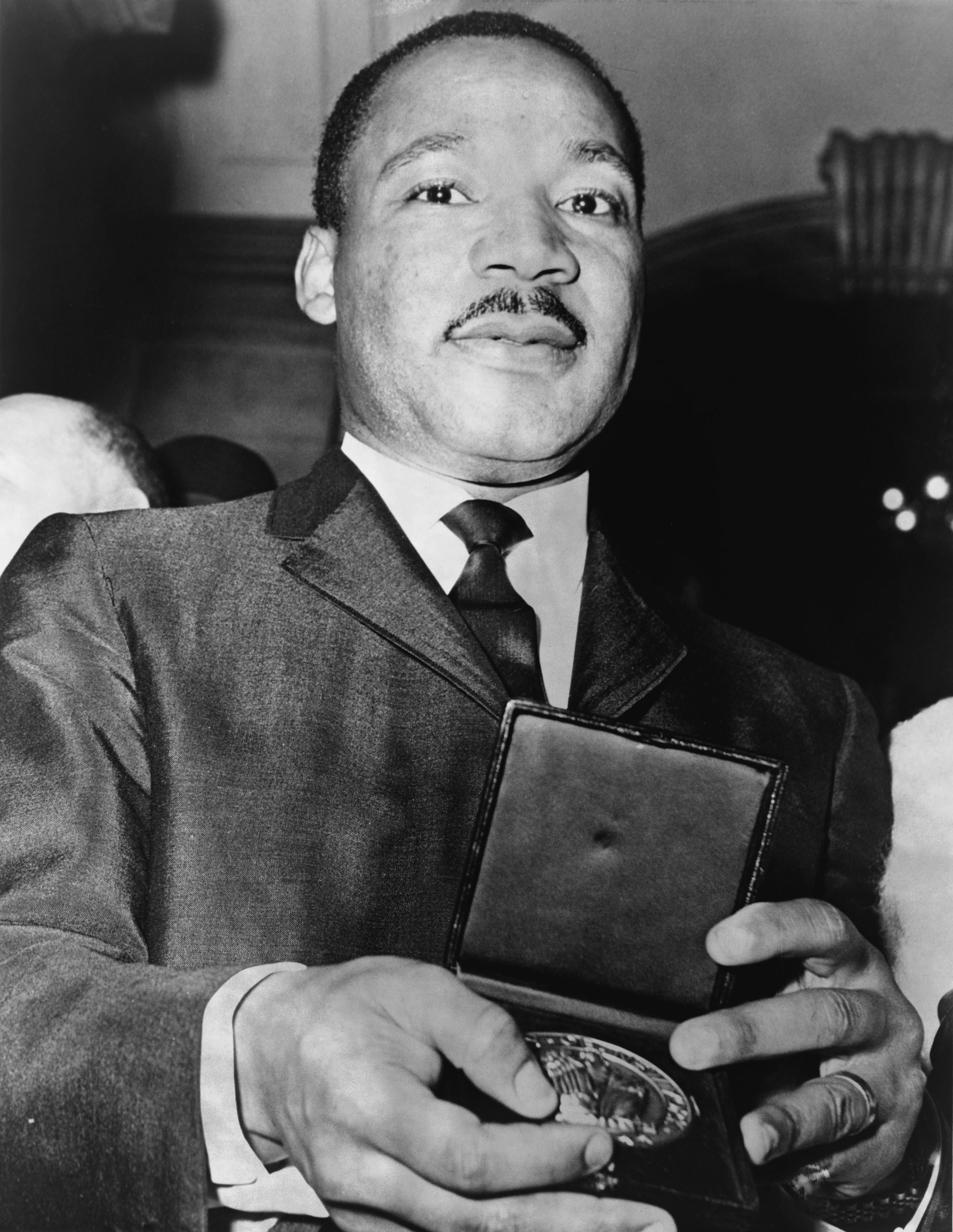

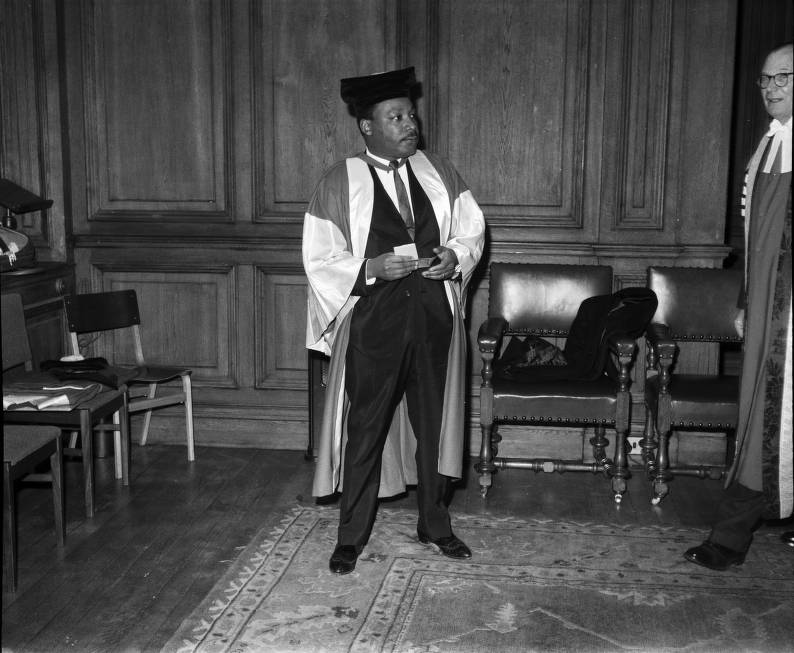

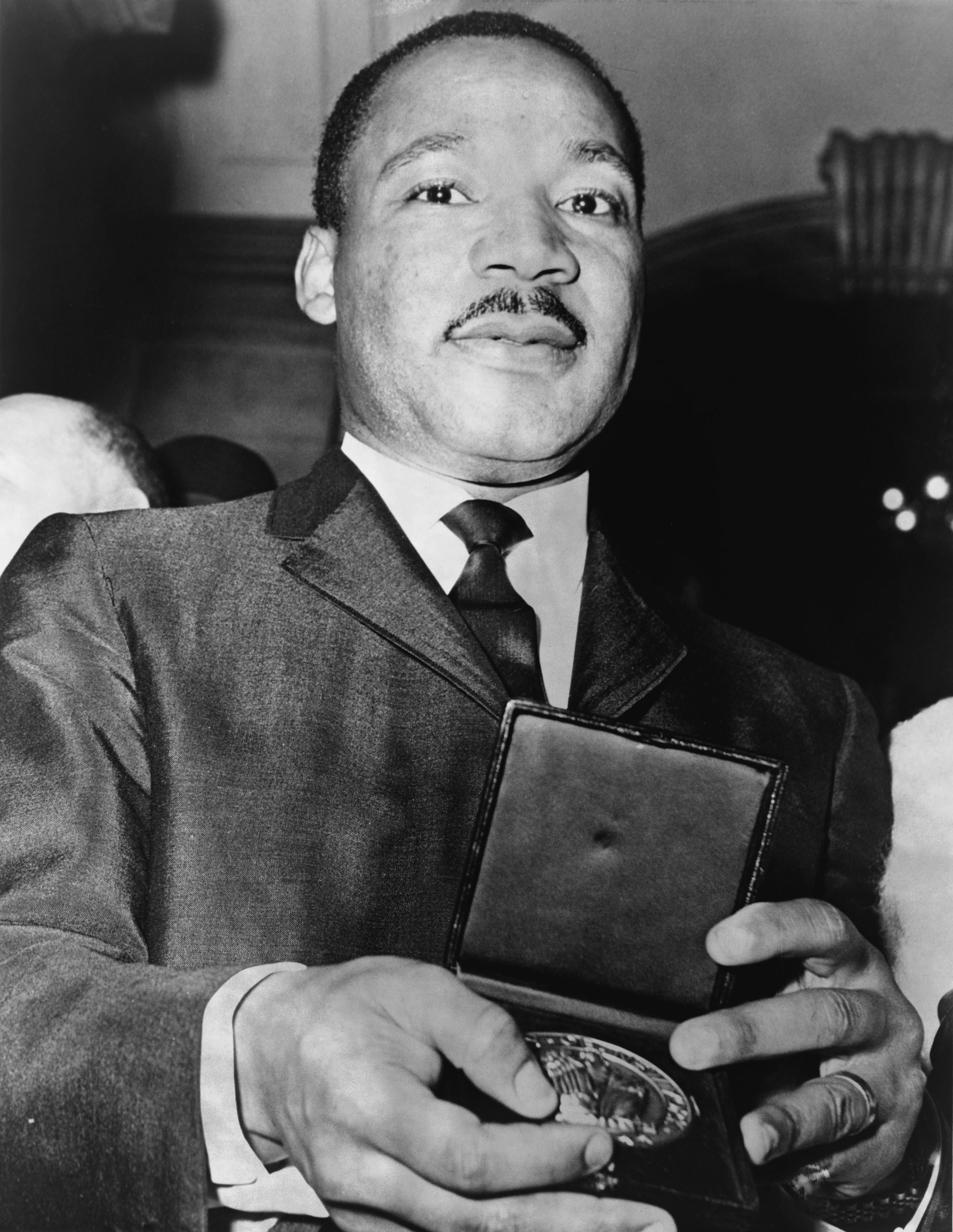

King won the

1964 Nobel Peace Prize for combating

racial inequality

Social inequality occurs when resources within a society are distributed unevenly, often as a result of inequitable allocation practices that create distinct unequal patterns based on socially defined categories of people. Differences in acce ...

through nonviolent resistance. In his final years, he expanded his focus to include opposition towards

poverty

Poverty is a state or condition in which an individual lacks the financial resources and essentials for a basic standard of living. Poverty can have diverse Biophysical environmen ...

and the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

.

In 1968, King was planning a national occupation of Washington, D.C., to be called the

Poor People's Campaign, when he was assassinated on April 4 in

Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

.

James Earl Ray, a

fugitive

A fugitive or runaway is a person who is fleeing from custody, whether it be from jail, a government arrest, government or non-government questioning, vigilante violence, or outraged private individuals. A fugitive from justice, also known ...

from the

Missouri State Penitentiary, was convicted of the assassination, though the King family believes he was a

scapegoat

In the Bible, a scapegoat is one of a pair of kid goats that is released into the wilderness, taking with it all sins and impurities, while the other is sacrificed. The concept first appears in the Book of Leviticus, in which a goat is designate ...

. After a 1999

wrongful death lawsuit ruling named unspecified "government agencies" among the co-conspirators,

a Department of Justice investigation found no evidence of a conspiracy. The assassination remains

the subject of conspiracy theories. King's death was followed by

national mourning, as well as anger leading to

riots in US cities. King was posthumously awarded the

Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, alongside the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by decision of the president of the United States to "any person recommended to the President ...

in 1977 and

Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is the oldest and highest civilian award in the United States, alongside the Presidential Medal of Freedom. It is bestowed by vote of the United States Congress, signed into law by the president. The Gold Medal exp ...

in 2003.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day

Martin Luther King Jr. Day (officially Birthday of Martin Luther King Jr., and often referred to shorthand as MLK Day) is a federal holiday in the United States observed on the third Monday of January each year. King was the chief spokespers ...

was established as a holiday in cities and states throughout the United States beginning in 1971; the federal holiday was first observed in 1986. The

Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial on the

National Mall

The National Mall is a Landscape architecture, landscaped park near the Downtown, Washington, D.C., downtown area of Washington, D.C., the capital city of the United States. It contains and borders a number of museums of the Smithsonian Institu ...

in Washington, D.C., was dedicated in 2011.

Early life and education

Birth

Michael King Jr. was born on January 15, 1929, in

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

; he was the second of three children born to

Michael King Sr. and

Alberta King ().

Alberta's father, Adam Daniel Williams,

was a minister in rural

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

, moved to Atlanta in 1893,

and became pastor of the

Ebenezer Baptist Church in the following year. Williams married Jennie Celeste Parks.

Michael Sr. was born to

sharecroppers James Albert and Delia King of

Stockbridge, Georgia

Stockbridge is a city in Henry County, Georgia, Henry County, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States. As of 2020, its population was 28,973. Stockbridge is part of the Atlanta metropolitan area.

History

The area was settled in 1829 when C ...

;

he was of

Irish and likely

Mende (

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

) descent. As an adolescent, Michael Sr. left his parents' farm and walked to Atlanta, where he attained a high school education, and enrolled in

Morehouse College

Morehouse College is a Private college, private, Historically black colleges and universities, historically black, Men's colleges in the United States, men's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia, ...

to study for entry to the ministry. Michael Sr. and Alberta began dating in 1920, and married on November 25, 1926. Until Jennie's death in 1941, their home was on the second floor of Alberta's parents'

Victorian house, where King was born. Michael Jr. had an older sister,

Christine King Farris, and a younger brother,

Alfred Daniel "A. D." King.

Shortly after marrying Alberta, Michael King Sr. became assistant pastor of the Ebenezer church. Senior pastor Williams died in the spring of 1931 and that fall Michael Sr. took the role. With support from his wife, he raised attendance from six hundred to several thousand.

In 1934, the church sent King Sr. on a multinational trip; one of the stops being Berlin for the Fifth Congress of the

Baptist World Alliance

The Baptist World Alliance (BWA) is an international communion of Baptists, with an estimated 51 million people from 266 member bodies in 134 countries and territories as of 2024. A voluntary association of Baptist churches, the BWA accounts f ...

(BWA).

He also visited sites in

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

that are associated with the

Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

leader

Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

.

In reaction to the rise of

Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

, the Congress of the BWA adopted, in August 1934, a resolution saying, "This Congress deplores and condemns as a violation of the law of God the Heavenly Father, all racial animosity, and every form of oppression or unfair discrimination toward the Jews, toward colored people, or toward subject races in any part of the world."

After returning home in August 1934, Michael Sr. changed his name to Martin Luther King Sr. and his five-year-old son's name to Martin Luther King Jr.

Early childhood

At his childhood home, Martin King Jr. and his two siblings read aloud the

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

as instructed by their father. After dinners, Martin Jr.'s grandmother Jennie, whom he affectionately referred to as "Mama", told lively stories from the

Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

. Martin Jr.'s father regularly used

whipping

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed on ...

s to discipline his children, sometimes having them whip each other. Martin Sr. later remarked, "

artin Jr.was the most peculiar child whenever you whipped him. He'd stand there, and the tears would run down, and he'd never cry." Once, when Martin Jr. witnessed his brother A.D. emotionally upset his sister Christine, he took a telephone and knocked A.D. unconscious with it. When Martin Jr. and his brother were playing at their home, A.D. slid from a banister and hit Jennie, causing her to fall unresponsive. Martin Jr., believing her dead, blamed himself and attempted

suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death.

Risk factors for suicide include mental disorders, physical disorders, and substance abuse. Some suicides are impulsive acts driven by stress (such as from financial or ac ...

by jumping from a second-story window, but rose from the ground after hearing that she was alive.

Martin King Jr. became friends with a white boy whose father owned a business across the street from his home. In September 1935, when the boys were about six years old, they started school. King had to attend a school for black children, Yonge Street Elementary School, while his playmate went to a separate school for white children only. Soon afterwards, the parents of the white boy stopped allowing King to play with their son, stating to him, "we are white, and you are colored". When King relayed this to his parents, they talked with him about the history of

slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

and

racism in America, which King would later say made him "determined to hate every white person". His parents instructed him that it was his

Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

duty to love everyone.

Martin King Jr. witnessed his father stand up against

segregation Segregation may refer to:

Separation of people

* Geographical segregation, rates of two or more populations which are not homogenous throughout a defined space

* School segregation

* Housing segregation

* Racial segregation, separation of human ...

and

discrimination

Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong, such as race, gender, age, class, religion, or sex ...

. Once, when stopped by a police officer who referred to Martin Sr. as "boy", Martin Sr. responded sharply that Martin Jr. was a boy but he was a man. When Martin Jr's father took him into a shoe store in downtown Atlanta, the clerk told them they needed to sit in the back. Martin Sr. refused, asserting "We'll either buy shoes sitting here or we won't buy any shoes at all", before leaving the store with Martin Jr. He told Martin Jr. afterward, "I don't care how long I have to live with this system, I will never accept it." In 1936, Martin Sr. led hundreds of African Americans in a

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

march to the

city hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or municipal hall (in the Philippines) is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses the city o ...

in Atlanta to protest

voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

discrimination. Martin Jr. later remarked that Martin Sr. was "a real father" to him.

Martin King Jr. memorized

hymns

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' ...

and Bible verses by the time he was five years old. Beginning at six years old, he attended church events with his mother and sang hymns while she played piano. His favorite hymn was "I Want to Be More and More Like Jesus". King later became a member of the junior choir in his church. He enjoyed opera, and played the piano. King garnered a large vocabulary from reading dictionaries. He got into physical altercations with boys in his neighborhood, but oftentimes used his knowledge of words to stop or avoid fights. King showed a lack of interest in grammar and spelling, a trait that persisted throughout his life. In 1939, King sang as a member of his church choir dressed as a

slave

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

for the all-white audience at the Atlanta premiere of the film ''

Gone with the Wind Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* Gone with the Wind (novel), ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* Gone with the Wind (film), ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind ...

''.

In September 1940, at the age of 11, King was enrolled at the Atlanta University Laboratory School for the

seventh grade

Seventh grade (also 7th Grade or Grade 7) is the seventh year of formal or compulsory education. The seventh grade is typically the first or second year of middle school. In the United States, kids in seventh grade are usually around 12–13 years ...

. While there, King took

violin

The violin, sometimes referred to as a fiddle, is a wooden chordophone, and is the smallest, and thus highest-pitched instrument (soprano) in regular use in the violin family. Smaller violin-type instruments exist, including the violino picc ...

and

piano

A piano is a keyboard instrument that produces sound when its keys are depressed, activating an Action (music), action mechanism where hammers strike String (music), strings. Modern pianos have a row of 88 black and white keys, tuned to a c ...

lessons and showed keen interest in history and

English classes.

On May 18, 1941, when King had sneaked away from studying at home to watch a parade, he was informed that something had happened to his maternal grandmother. After returning home, he learned she had a heart attack and died while being transported to a hospital. He took her death very hard and believed that his deception in going to see the parade may have been responsible for God taking her. King again jumped out of a second-story window at his home but again survived. His father instructed him that Martin Jr. should not blame himself and that she had been called home to God as part of God's plan. Martin Jr. struggled with this. Shortly thereafter, Martin Sr. decided to move the family to a two-story brick home on a hill overlooking downtown Atlanta.

Adolescence

As an adolescent, he initially felt resentment against whites due to the "racial humiliation" that he, his family, and his neighbors often had to endure. In 1942, when King was 13, he became the youngest assistant manager of a newspaper delivery station for the ''

Atlanta Journal''. In the same year, King skipped the ninth grade and enrolled in

Booker T. Washington High School, where he maintained a B-plus average. The high school was the only one in the city for African-American students.

Martin Jr. was brought up in a

Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

home; as he entered adolescence he began to question the

literalist teachings preached at his father's church. At the age of 13, he denied the

bodily resurrection of Jesus during

Sunday school

]

A Sunday school, sometimes known as a Sabbath school, is an educational institution, usually Christianity, Christian in character and intended for children or neophytes.

Sunday school classes usually precede a Sunday church service and are u ...

.

Martin Jr. said that he found himself unable to identify with the emotional displays from congregants who were frequent at his church; he doubted if he would ever attain personal satisfaction from religion. He later said of this point in his life, "doubts began to spring forth unrelentingly."

In high school, Martin King Jr. became known for his public-speaking ability, with a voice that had grown into an orotund

baritone

A baritone is a type of classical music, classical male singing human voice, voice whose vocal range lies between the bass (voice type), bass and the tenor voice type, voice-types. It is the most common male voice. The term originates from the ...

. He joined the school's debate team. King continued to be most drawn to history and

English, and chose English and

sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

as his main subjects. King maintained an abundant

vocabulary

A vocabulary (also known as a lexicon) is a set of words, typically the set in a language or the set known to an individual. The word ''vocabulary'' originated from the Latin , meaning "a word, name". It forms an essential component of languag ...

. However, he relied on his sister Christine to help him with spelling, while King assisted her with math. King also developed an interest in fashion, commonly wearing polished

patent leather

Patent leather is a type of coated leather that has a high-gloss finish.

In general, patent leather is fine grain leather that is treated to give it a glossy appearance. Characterized by a glass-like finish that catches the light, patent leath ...

shoes and

tweed

Tweed is a rough, woollen fabric, of a soft, open, flexible texture, resembling cheviot or homespun, but more closely woven. It is usually woven with a plain weave, twill or herringbone structure. Colour effects in the yarn may be obtained ...

suits, which gained him the nickname "Tweed" or "Tweedie" among his friends. He liked flirting with girls and dancing. His brother A.D. later remarked, "He kept flitting from chick to chick, and I decided I couldn't keep up with him. Especially since he was crazy about dances, and just about the best jitterbug in town."

On April 13, 1944, in his

junior year, King gave his first public speech during an

oratorical contest.

In his speech he stated, "black America still wears chains. The finest negro is at the mercy of the meanest white man."

King was selected as the winner of the contest.

On the ride home to Atlanta by bus, he and his teacher were ordered by the driver to stand so that white passengers could sit. The driver of the bus called King a "black son-of-a-bitch". King initially refused but complied after his teacher told him that he would be breaking the law if he did not. As all the seats were occupied, he and his teacher were forced to stand the rest of the way to Atlanta. Later King wrote of the incident: "That night will never leave my memory. It was the angriest I have ever been in my life."

Morehouse College

During King's junior year in high school,

Morehouse College

Morehouse College is a Private college, private, Historically black colleges and universities, historically black, Men's colleges in the United States, men's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia, ...

—an all-male

historically black college

Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of serving African Americans. Most are in the Southern U ...

that King's father and maternal grandfather had attended—began accepting high school juniors who passed the

entrance examination

In education, an entrance examination or admission examination is an examination that educational institutions conduct to select prospective students. It may be held at any stage of education, from primary to tertiary, even though it is typica ...

. As

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

was underway, many black college students had been enlisted, so the university aimed to increase their enrollment by allowing juniors to apply. In 1944, aged 15, King passed the examination and was enrolled at the university that autumn.

In the summer before King started at Morehouse, he boarded a train with his friend—Emmett "Weasel" Proctor—and a group of other Morehouse College students to work in

Simsbury, Connecticut

Simsbury is a town in Hartford County, Connecticut, United States, incorporated as Connecticut's 21st town in May 1670. The town is part of the Capitol Planning Region. The population was 24,517 in the 2020 census.

History

Early history

At ...

, at the

tobacco farm of Cullman Brothers Tobacco.

This was King's first trip into the

integrated north.

In a June 1944 letter to his father, King wrote about the differences that struck him: "On our way here we saw some things I had never anticipated to see. After we passed Washington there was no discrimination at all. The white people here are very nice. We go to any place we want to and sit anywhere we want to."

The farm had partnered with Morehouse College to allot their wages towards the university's tuition, housing, and fees.

On weekdays King and the other students worked in the fields, picking tobacco from 7:00 am to at least 5:00 pm, enduring temperatures above 100

°F, to earn roughly USD$4 per day.

On Friday evenings, the students visited downtown Simsbury to get milkshakes and watch movies, and on Saturdays they would travel to

Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. The city, located in Hartford County, Connecticut, Hartford County, had a population of 121,054 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 ce ...

, to see theatre performances, shop, and eat in restaurants.

On Sundays, they attended church services in Hartford at a church filled with white congregants.

King wrote to his parents about the lack of segregation, relaying how he was amazed they could go to "one of the finest restaurants in Hartford" and that "Negroes and whites go to the same church".

He played freshman football there. The summer before his last year at Morehouse, in 1947, the 18-year-old King chose to enter the

ministry. He would later credit the college's president,

Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

minister

Benjamin Mays, with being his "spiritual mentor". King had concluded that the church offered the most assuring way to answer "an inner urge to serve humanity", and he made peace with the Baptist Church, as he believed he would be a "rational" minister with sermons that were "a respectful force for ideas, even social protest." King graduated from Morehouse with a

Bachelor of Arts

A Bachelor of Arts (abbreviated B.A., BA, A.B. or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is the holder of a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the liberal arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts deg ...

in sociology in 1948, aged nineteen.

Religious education

King enrolled in

Crozer Theological Seminary in

Upland, Pennsylvania,

and took several courses at the

University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

.

At Crozer, King was elected president of the student body. At Penn, King took courses with

William Fontaine, Penn's first African-American professor, and

Elizabeth F. Flower, a professor of philosophy. King's father supported his decision to continue his education and made arrangements for King to work with

J. Pius Barbour, a family friend and Crozer alumnus who pastored at

Calvary Baptist Church in nearby

Chester, Pennsylvania

Chester is a city in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located in the Philadelphia metropolitan area (also known as the Delaware Valley) on the western bank of the Delaware River between Philadelphia and Wilmington, Delaware. ...

. King became known as one of the "Sons of Calvary", an honor he shared with

William Augustus Jones Jr. and

Samuel D. Proctor, who both went on to become well-known preachers.

King reproved another student for keeping beer in his room once, saying they shared responsibility as African Americans to bear "the burdens of the Negro race". For a time, he was interested in

Walter Rauschenbusch

Walter Rauschenbusch (1861–1918) was an American theologian and Baptist pastor who taught at the Rochester Theological Seminary. Rauschenbusch was a key figure in the Social Gospel and single tax movements that flourished in the United States ...

's "social gospel". In his third year at Crozer, King became romantically involved with

the white daughter of an immigrant German woman who worked in the cafeteria. King planned to marry her, but friends, as well as King's father,

advised against it, saying that an interracial marriage would provoke animosity from both blacks and whites, potentially damaging his chances of ever pastoring a church in the South. King tearfully told a friend that he could not endure his mother's pain over the marriage and broke the relationship off six months later. One friend was quoted as saying, "He never recovered." Other friends, including

Harry Belafonte

Harry Belafonte ( ; born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr.; March 1, 1927 – April 25, 2023) was an American singer, actor, and civil rights activist who popularized calypso music with international audiences in the 1950s and 1960s. Belafonte ...

, said Betty had been "the love of King's life."

King graduated with a

Bachelor of Divinity

In Western universities, a Bachelor of Divinity or Baccalaureate in Divinity (BD, DB, or BDiv; ) is an academic degree awarded for a course taken in the study of divinity or related disciplines, such as theology or, rarely, religious studies.

...

in 1951.

He applied to the University of Edinburgh for a doctorate in the School of Divinity but ultimately chose Boston instead.

In 1951, King began doctoral studies in

systematic theology

Systematic theology, or systematics, is a discipline of Christian theology that formulates an orderly, rational, and coherent account of the doctrines of the Christian faith. It addresses issues such as what the Bible teaches about certain topics ...

at

Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a Private university, private research university in Boston, Massachusetts, United States. BU was founded in 1839 by a group of Boston Methodism, Methodists with its original campus in Newbury (town), Vermont, Newbur ...

,

and worked as an assistant minister at Boston's historic

Twelfth Baptist Church with William Hunter Hester. Hester was an old friend of King's father and was an important influence on King. In Boston, King befriended a small cadre of local ministers his age, and sometimes guest pastored at their churches, including

Michael E. Haynes, associate pastor at Twelfth Baptist Church in Roxbury. The young men often held bull sessions in their apartments, discussing theology, sermon style, and social issues.

At the age of 25 in 1954, King was

called as pastor of the

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in

Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama. Named for Continental Army major general Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River on the Gulf Coastal Plain. The population was 2 ...

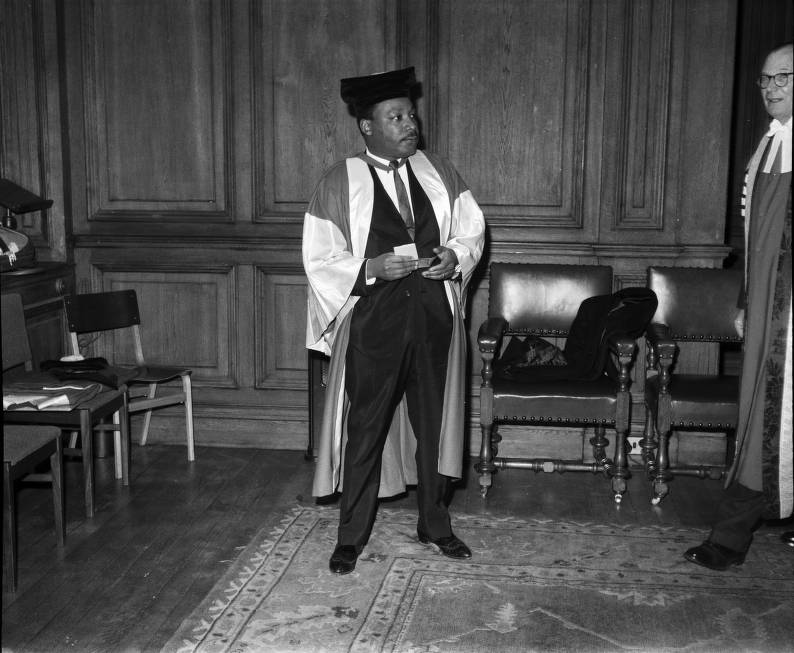

. King received his PhD on June 5, 1955, with a

dissertation (initially supervised by

Edgar S. Brightman and, upon the latter's death, by

Lotan Harold DeWolf) titled ''A Comparison of the Conceptions of God in the Thinking of

Paul Tillich

Paul Johannes Tillich (; ; August 20, 1886 – October 22, 1965) was a German and American Christian existentialist philosopher, religious socialist, and Lutheran theologian who was one of the most influential theologians of the twenti ...

and

Henry Nelson Wieman

Henry Nelson Wieman (1884–1975) was an American philosopher and theologian. He became the most famous proponent of theocentric naturalism and the empirical method in American theology and catalyzed the emergence of religious naturalism in t ...

''.

An academic inquiry in October 1991 concluded that portions of his doctoral dissertation had been

plagiarized and he had acted improperly. However, its finding, the committee said that 'no thought should be given to the revocation of Dr. King's doctoral degree,' an action that the panel said would serve no purpose."

The committee found that the dissertation still "makes an intelligent contribution to scholarship." A letter is now attached to the copy of King's dissertation in the university library, noting that numerous passages were included without the appropriate quotations and citations of sources. Significant debate exists on how to interpret King's plagiarism.

Marriage and family

While studying at Boston University, he asked a friend from Atlanta named Mary Powell, a student at the

New England Conservatory of Music

The New England Conservatory of Music (NEC) is a Private college, private music school in Boston, Massachusetts. The conservatory is located on Huntington Avenue along Avenue of the Arts (Boston), the Avenue of the Arts near Boston Symphony Ha ...

, if she knew any nice Southern girls. Powell spoke to fellow student

Coretta Scott; Scott was not interested in dating preachers but eventually agreed to allow King to telephone her based on Powell's description and vouching. On their first call, King told Scott, "I am like Napoleon at Waterloo before your charms," to which she replied, "You haven't even met me." King married Scott on June 18, 1953, on the lawn of her parents' house, in

Heiberger, Alabama. They had four children:

Yolanda King (1955–2007),

Martin Luther King III (b. 1957),

Dexter Scott King (1961–2024), and

Bernice King (b. 1963).

King limited Coretta's role in the civil rights movement, expecting her to be a housewife and mother.

Activism and organizational leadership

Mary's Cafe Sit-In, 1950

On Sunday, June 11, 1950, King, classmate at Crozer Seminary and housemate Walter McCall, and their dates Doris Wilson and Pearl Smith attended church services in Merchantville. Afterwards they stopped at tavern Mary's Cafe in Maple Shade for beers. The foursome were left waiting without anyone approaching them for service, not unexpectedly. A friend's father and King and McCall's landlord Jesthroe Hunt had warned them Black people were not welcome at Mary's. King replied to the effect of maybe they needed to go, so they could start to go anywhere they wanted. The seminarians had opted for Mary's Cafe with full knowledge of its reputation. After waiting without service, McCall approached the bar.

McCall asked bartender and Mary's Cafe owner Ernest Nichols for packaged goods (beer for takeaway). Nichols refused, explaining he couldn't sell packaged goods on Sundays or any day after 10pm, by law. McCall then requested 4 glasses of beer to which Nichols answered "no beer, Mr! Today is Sunday”.

Nichols would claim they sought him to violate New Jersey's

blue law

Blue laws (also known as Sunday laws, Sunday trade laws, and Sunday closing laws) are laws restricting or banning certain activities on specified days, usually Sundays in the western world. The laws were adopted originally for Religion, religio ...

(a restriction common in South Jersey and Pennsylvania as a remnant of the influence of their

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

roots).

McCall requested ginger ales as non-alcoholic beverages were not subject to the blue law. Nichols refused the group even ginger ales and reportedly stated "the best thing would be for you to leave".

King and company met refusal with refusal, and remained in their seats as was their right per New Jersey's 1945 anti-discrimination law, which guaranteed non-discrimination by race in public accommodations. Nichols stomped out and returned with a gun standing outside firing into the air reportedly shouting "I'd kill for less".

Fearing for their lives, the four activists ran from the tavern. The group went to the Maple Shade Police Department where officers refused to file their complaint. King and McCall contacted

Ulysses Simpson Wiggins then President of the Camden County Branch

NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

, who helped them successfully file a police report. The New York Times confirms "The complaint was against Ernest Nichols, a white tavern owner in Maple Shade, N.J., and said that he had refused to serve the black students and their dates in June 1950, and had threatened them by firing a gun in the air. The complaint was signed by the two students. One of the signatures, in a loopy, slanted cursive, reads 'M. L. King Jr.'"

Nichols was charged with disorderly conduct and violation of the anti-discrimination law. He was found guilty and fined $50, however the racial discrimination count was dismissed. In a statement submitted "in the spirit of assisting the Prosecutor"

Nichol's attorney noted:

King cited the incident saying it was “a formative step” in his “commitment to a more just society.”

The Mary's Cafe

sit-in

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

demonstrated the power of

non-violent civil disobedience

Civil disobedience is the active and professed refusal of a citizenship, citizen to obey certain laws, demands, orders, or commands of a government (or any other authority). By some definitions, civil disobedience has to be nonviolent to be cal ...

. Nichols' reaction in retrieving a weapon and discharging it to scare the group, or summon his guard dog, to young people's refusal to leave unserved, showed King the potency of such tactics. This sit-in is believed to be the first deployment of the non-violence and civil disobedience tactics which would distinguish King's activism and legacy.

The Mary's Cafe sit-in occurred six months prior to

Mordecai Johnson's Lecture on Gandi at the

First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia on November 19, 1950 where King would be formally exposed to these tactics. At that lecture and in discussions with Dr. Johnson at the Fellowship House, Dr. King would be inspired and galvanized by how

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

integrated

Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (born David Henry Thoreau; July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon sim ...

's theory of

Nonviolent resistance

Nonviolent resistance, or nonviolent action, sometimes called civil resistance, is the practice of achieving goals such as social change through symbolic protests, civil disobedience, economic or political noncooperation, satyagraha, construct ...

and civil disobedience tactics. Patrick Duff, a South Jersey resident, discovered the police report detailing the events at Mary's after searching the archive at

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.

Montgomery bus boycott, 1955

The

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church was influential in the Montgomery African-American community. As the church's pastor, King became known for his oratorical preaching in Montgomery and surrounding region.

In March 1955,

Claudette Colvin—a black schoolgirl in Montgomery—refused to give up her bus seat to a white man in violation of

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

, local laws in the Southern US that enforced

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

. On December 1, 1955,

Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an American civil rights activist. She is best known for her refusal to move from her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, in defiance of Jim Crow laws, which sparke ...

was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a city bus. These incidents led to the

Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social boycott, protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United ...

, which was urged and planned by

Edgar Nixon and led by King. The other ministers asked him to take a leadership role because his relative newness to community leadership made it easier for him to speak out. King was hesitant but decided to do so if no one else wanted it.

[Interview with Coretta Scott King, Episode 1, PBS TV series Eyes on the Prize.]

The boycott lasted for 385 days, and the situation became so tense that King's house was bombed. King was arrested for traveling 30 mph in a 25 mph zone and jailed, which drew the attention of national media, and increased King's public stature. The controversy ended when the US District Court issued a ruling in ''

Browder v. Gayle'' that prohibited racial segregation on Montgomery public buses.

King's role in the bus boycott transformed him into a national figure and the best-known spokesman of the civil rights movement.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In 1957, King,

Ralph Abernathy

Ralph David Abernathy Sr. (; March 11, 1926 – April 17, 1990) was an American civil rights activist and Baptist minister. He was ordained in the Baptist tradition in 1948. Being the leader of the civil rights movement, he was a close frien ...

,

Fred Shuttlesworth

Freddie Lee Shuttlesworth (born Freddie Lee Robinson, March 18, 1922 – October 5, 2011) was an American Baptist minister and civil rights activist who led fights against segregation and other forms of racism, during the civil rights movement. ...

,

Joseph Lowery, and other activists founded the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African Americans, African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., ...

(SCLC). The group was created to harness the

moral authority

Moral authority is authority premised on principles, or fundamental truths, which are independent of written, or positive laws. As such, moral authority necessitates the existence of and adherence to truth. Because truth does not change the princip ...

and organizing power of black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the service of civil rights reform. The group was inspired by the crusades of evangelist

Billy Graham

William Franklin Graham Jr. (; November 7, 1918 – February 21, 2018) was an American Evangelism, evangelist, ordained Southern Baptist minister, and Civil rights movement, civil rights advocate, whose broadcasts and world tours featuring liv ...

, who befriended King, as well as the national organizing of the group In Friendship, founded by King allies

Stanley Levison and

Ella Baker

Ella Josephine Baker (December 13, 1903 – December 13, 1986) was an African-American civil rights and human rights activist. She was a largely behind-the-scenes organizer whose career spanned more than five decades. In New York City and ...

. King led the SCLC until his death. The SCLC's 1957

Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom was the first time King addressed a national audience.

Harry Wachtel joined King's legal advisor

Clarence B. Jones in defending four ministers of the SCLC in the libel case ''

Abernathy et al. v. Sullivan''; the case was litigated about the newspaper advertisement "

Heed Their Rising Voices

"Heed Their Rising Voices" is a 1960 newspaper advertisement published in ''The New York Times''. It was published on March 29, 1960 and paid for by the "Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South". The purp ...

". Wachtel founded a tax-exempt fund to cover the suit's expenses and assist the civil rights movement through more effective fundraising. King served as honorary president of this organization, named the "Gandhi Society for Human Rights". In 1962, King and the Gandhi Society produced a document that called on

President Kennedy to issue an executive order to deliver a blow for civil rights as a kind of

Second Emancipation Proclamation. Kennedy did not execute the order.

The

FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

, under written directive from Attorney General

Robert F. Kennedy, began

tapping

Tapping is a playing technique that can be used on any stringed instrument, but which is most commonly used on guitar. The technique involves a string being fretted and set into vibration as part of a single motion. This is in contrast to stand ...

King's telephone line in the fall of 1963. Kennedy was concerned that public allegations of communists in the SCLC would derail the administration's civil rights initiatives. He warned King to discontinue these associations and felt compelled to issue the directive that authorized the FBI to wiretap King and other SCLC leaders. FBI Director

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American attorney and law enforcement administrator who served as the fifth and final director of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) and the first director of the Federal Bureau o ...

feared the civil rights movement and investigated the allegations of communist infiltration. When no evidence emerged to support this, the FBI used the incidental details caught on tape over the next five years, as part of its

COINTELPRO

COINTELPRO (a syllabic abbreviation derived from Counter Intelligence Program) was a series of covert and illegal projects conducted between 1956 and 1971 by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltr ...

program, in attempts to force King out of his leadership position.

King believed that organized, nonviolent protest against the system of southern segregation known as

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were U.S. state, state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, "Jim Crow (character), Ji ...

would lead to extensive media coverage of the struggle for black equality. Journalistic accounts and televised footage of the daily indignities suffered by southern blacks, and of segregationist violence and harassment, produced a wave of sympathetic public opinion that convinced most Americans that the civil rights movement was the most important political issue in the early 1960s.

King organized and led marches for blacks' right to

vote

Voting is the process of choosing officials or policies by casting a ballot, a document used by people to formally express their preferences. Republics and representative democracies are governments where the population chooses representative ...

,

desegregation,

labor rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, the ...

, and other basic civil rights. Most of these rights were successfully enacted into law with the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

and the 1965

Voting Rights Act

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights movem ...

. The SCLC used tactics of nonviolent protest with success, by strategically choosing the methods and places in which protests were carried out. There were often dramatic stand-offs with segregationist authorities, who sometimes turned violent.

Survived knife attack, 1958

On September 20, 1958, King was signing copies of his book ''

Stride Toward Freedom'' in Blumstein's department store in Harlem when

Izola Curry—a mentally ill black woman who thought King was conspiring against her with communists—stabbed him in the chest with a letter opener, which nearly impinged on the aorta. King received first aid by police officers

Al Howard and Philip Romano. King underwent surgery by

Aubre de Lambert Maynard,

Emil Naclerio and

John W. V. Cordice; he remained hospitalized for weeks. Curry was later found mentally incompetent to stand trial.

Atlanta sit-ins, prison sentence, and the 1960 elections

In December 1959, after being based in Montgomery for five years, King announced his return to Atlanta at the request of the SCLC. In Atlanta, King served until his death as co-pastor with his father at the

Ebenezer Baptist Church. Georgia governor

Ernest Vandiver expressed open hostility towards King's return. He claimed that "wherever M. L. King Jr., has been there has followed in his wake a wave of crimes", and vowed to keep King under surveillance. On May 4, 1960, King drove writer

Lillian Smith to

Emory University

Emory University is a private university, private research university in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. It was founded in 1836 as Emory College by the Methodist Episcopal Church and named in honor of Methodist bishop John Emory. Its main campu ...

when police stopped them. King was cited for "driving without a license" because he had not yet been issued a Georgia license. King's Alabama license was still valid, and Georgia law did not mandate any time limit for issuing a local license. King paid a fine but was unaware his lawyer agreed to a plea deal that included

probation

Probation in criminal law is a period of supervision over an offence (law), offender, ordered by the court often in lieu of incarceration. In some jurisdictions, the term ''probation'' applies only to community sentences (alternatives to incar ...

.

Meanwhile, the

Atlanta Student Movement

The Atlanta Student Movement was formed in February 1960 in Atlanta, Georgia by students of the campuses Atlanta University Center (AUC). It was led by the Committee on the Appeal for Human Rights (COAHR) and was part of the Civil Rights Mov ...

had been acting to desegregate businesses and public spaces, organizing the

Atlanta sit-ins

The Atlanta sit-ins were a series of sit-ins that took place in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Occurring during the sit-in movement of the larger civil rights movement, the sit-ins were organized by the Committee on Appeal for Human Righ ...

from March 1960 onwards. In August the movement asked King to participate in a mass October sit-in, timed to highlight how

1960's Presidential election campaigns had ignored civil rights. The coordinated day of action took place on October 19. King participated in a sit-in at the restaurant inside

Rich's, Atlanta's largest department store, and was among the many arrested. The authorities released everyone over the next few days, except King. Invoking his probationary plea deal, judge J. Oscar Mitchell sentenced King on October 25 to four months of hard labor. Before dawn the next day, King was transported to

Georgia State Prison

Georgia State Prison was the main maximum-security facility in the US state of Georgia for the Georgia Department of Corrections. It was located in unincorporated Tattnall County. First opened in 1938, the prison housed some of the most da ...

.

The arrest and harsh sentence drew nationwide attention. Many feared for King's safety, as he started a sentence with people convicted of violent crimes, many white and hostile to his activism. Presidential candidates were asked to weigh in, at a time when parties were courting the support of Southern Whites and their political leadership including Governor Vandiver. Nixon, with whom King had a closer relationship before, declined to make a statement despite a visit from

Jackie Robinson

Jack Roosevelt Robinson (January 31, 1919 – October 24, 1972) was an American professional baseball player who became the first Black American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB) in the modern era. Robinson broke the Baseball color line, ...

requesting his intervention. Nixon's opponent

John F. Kennedy called the governor, enlisted his brother

Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, prais ...

to exert more pressure on state authorities, and, at the request of

Sargent Shriver

Robert Sargent Shriver Jr. (November 9, 1915 – January 18, 2011) was an American diplomat, politician, and activist. He was a member of the Shriver family by birth, and a member of the Kennedy family through his marriage to Eunice Kennedy. ...

, called King's wife to offer his help. The pressure from Kennedy and others proved effective, and King was released two days later. King's father decided to openly endorse Kennedy's candidacy for the November 8 election which he narrowly won.

After the October 19 sit-ins and following unrest, a 30-day truce was declared in Atlanta for desegregation negotiations. However, negotiations failed and sit-ins and boycotts resumed for several months. On March 7, 1961, a group of Black elders including King notified student leaders that a deal had been reached: the city's lunch counters would desegregate in fall 1961, in conjunction with the court-mandated desegregation of schools. Many students were disappointed at the compromise. In a meeting on March 10 at Warren Memorial Methodist Church, the audience was hostile and frustrated. King gave an impassioned speech calling participants to resist the "cancerous disease of disunity", helping to calm tensions.

Albany Movement, 1961

The Albany Movement was a desegregation coalition formed in

Albany, Georgia

Albany ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. Located on the Flint River, it is the county seat of Dougherty County, Georgia, Dougherty County, and is the sole incorporated city in that county. Located in Southwest Geo ...

, in November 1961. In December, King and the SCLC became involved. The movement mobilized thousands of citizens for a nonviolent attack on segregation in the city and attracted nationwide attention. When King first visited on December 15, 1961, he "had planned to stay a day or so and return home after giving counsel."

The following day he was swept up in a

mass arrest of peaceful demonstrators, and he declined bail until the city made concessions. According to King, "that agreement was dishonored and violated by the city" after he left.

King returned in July 1962 and was given the option of 45 days in jail or a $178 fine (); he chose jail. Three days into his sentence, Police Chief Laurie Pritchett discreetly arranged for King's fine to be paid and ordered his release. "We had witnessed persons being kicked off lunch counter stools ... ejected from churches ... and thrown into jail ... But for the first time, we witnessed being kicked out of jail." It was later acknowledged by the King Center that

Billy Graham

William Franklin Graham Jr. (; November 7, 1918 – February 21, 2018) was an American Evangelism, evangelist, ordained Southern Baptist minister, and Civil rights movement, civil rights advocate, whose broadcasts and world tours featuring liv ...

was the one who bailed King out.

After nearly a year of intense activism with few tangible results, the movement began to deteriorate. King requested a halt to all demonstrations and a "Day of Penance" to promote nonviolence and maintain the moral high ground. Divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts. Though the Albany effort proved a key lesson in tactics for King and the civil rights movement, the national media was highly critical of King's role in the defeat, and the SCLC's lack of results contributed to a growing gulf between the organization and the more radical

SNCC

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and later, the Student National Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emer ...

. After Albany, King sought to choose engagements for the SCLC in which he could control the circumstances, rather than entering into pre-existing situations.

Birmingham campaign, 1963

In April 1963, the SCLC began a campaign against racial segregation and economic injustice in

Birmingham, Alabama

Birmingham ( ) is a city in the north central region of Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Jefferson County, Alabama, Jefferson County. The population was 200,733 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List ...

. The campaign used nonviolent but intentionally confrontational tactics, developed in part by

Wyatt Tee Walker. Black people in Birmingham, organizing with the SCLC, occupied public spaces with marches and sit-ins, openly violating laws that they considered unjust.

King's intent was to provoke mass arrests and "create a situation so crisis-packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation." The campaign's early volunteers did not succeed in shutting down the city, or in drawing media attention to the police's actions. Over the concerns of an uncertain King, SCLC strategist

James Bevel

James Luther Bevel (October 19, 1936 – December 19, 2008) was an American minister and a leader and major strategist of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. As a member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and then as its direct ...

changed the course of the campaign by recruiting children and young adults to join the demonstrations.

''

Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly news magazine based in New York City. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely distributed during the 20th century and has had many notable editors-in-chief. It is currently co-owned by Dev P ...

'' called this strategy a

Children's Crusade

The Children's Crusade was a failed Popular crusades, popular crusade by European Christians to establish a second Latin Church, Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem in the Holy Land in the early 13th century. Some sources have narrowed the date to 1212. ...

.

The Birmingham Police Department, led by

Eugene "Bull" Connor, used high-pressure water jets and police dogs against protesters, including children. Footage of the police response was broadcast on national television, shocking many white Americans and consolidating black Americans behind the movement. Not all demonstrators were peaceful, despite the avowed intentions of the SCLC. In some cases, bystanders attacked the police, who responded with force. King and the SCLC were criticized for putting children in harm's way. But the campaign was a success: Connor lost his job, the "Jim Crow" signs came down, and public places became more open to blacks. King's reputation improved immensely.

King was arrested and jailed early in the campaign—his 13th arrest

out of 29.

From his cell, he composed the now-famous "

Letter from Birmingham Jail

The "Letter from Birmingham Jail", also known as the "Letter from Birmingham City Jail" and "The Negro Is Your Brother", is an open letter written on April 16, 1963, by Martin Luther King Jr. It says that people have a moral responsibility to b ...

" that responds to

calls to pursue legal channels for social change. The letter has been described as "one of the most important historical documents penned by a modern

political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although ...

".

King argues that the crisis of racism is too urgent, and the current system too entrenched: "We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed."

He points out that the

Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was a seminal American protest, political and Mercantilism, mercantile protest on December 16, 1773, during the American Revolution. Initiated by Sons of Liberty activists in Boston in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colo ...

, a celebrated act of rebellion in the American colonies, was illegal civil disobedience, and that, conversely, "everything

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

did in Germany was 'legal'."

Walter Reuther

Walter Philip Reuther (; September 1, 1907 – May 9, 1970) was an American leader of organized labor and civil rights activist who built the United Automobile Workers (UAW) into one of the most progressive labor unions in American history. He ...

, president of the

United Auto Workers

The United Auto Workers (UAW), fully named International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico) and sou ...

, arranged for $160,000 to bail out King and his fellow protestors.

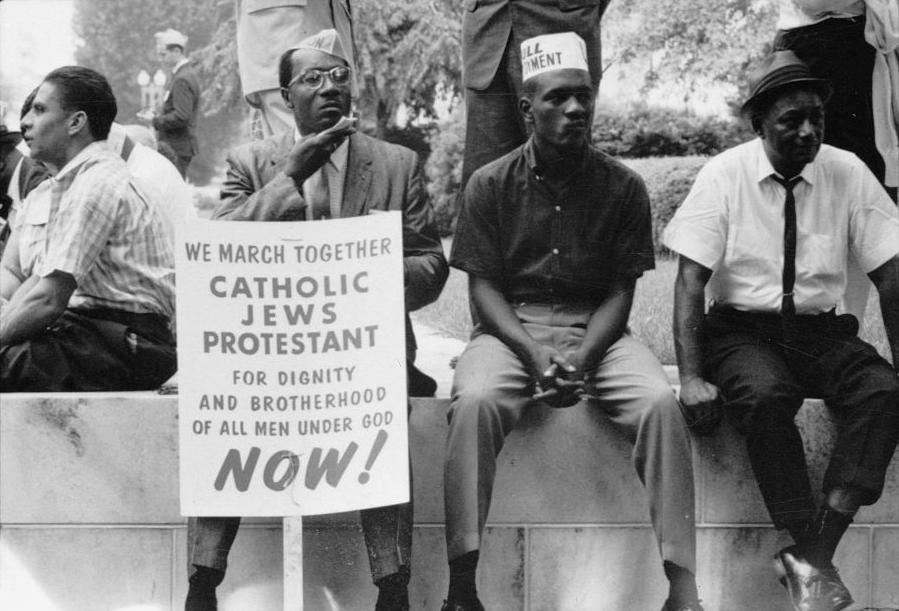

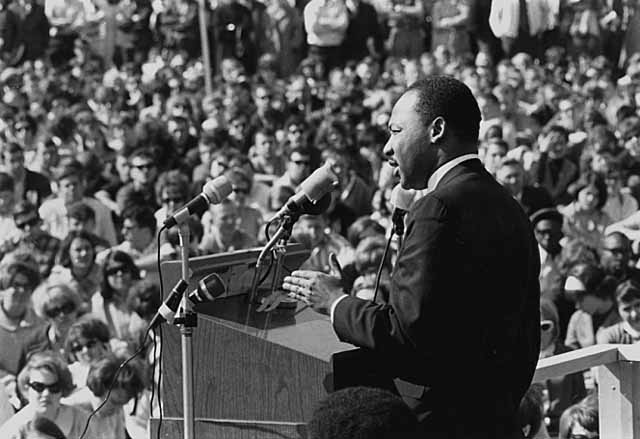

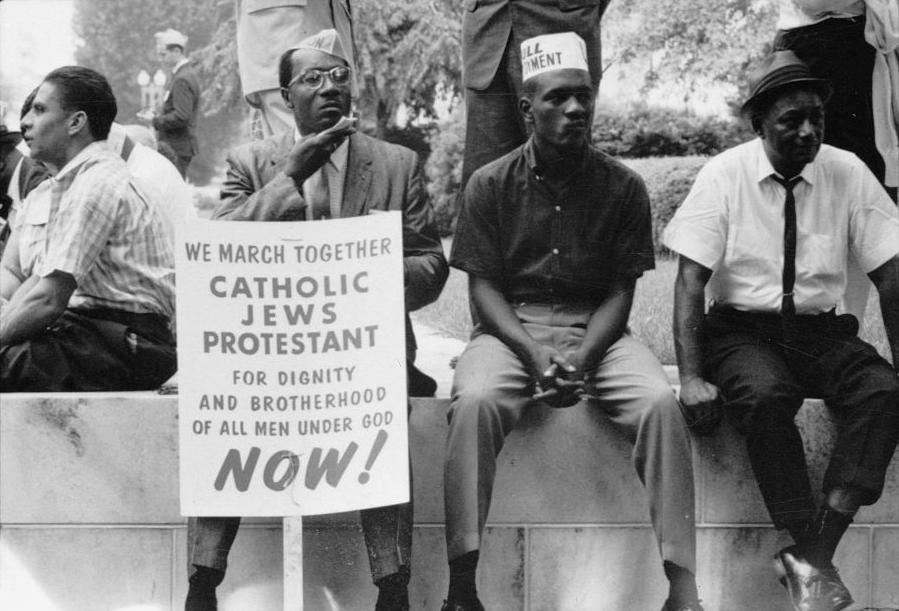

March on Washington, 1963

King, representing the

SCLC, was among the leaders of the "

Big Six" civil rights organizations who were instrumental in the organization of the ''March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom'', which took place on August 28, 1963. The other leaders and organizations comprising the Big Six were

Roy Wilkins

Roy Ottoway Wilkins (August 30, 1901 – September 8, 1981) was an American civil rights leader from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), ...

from the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

;

Whitney Young

Whitney Moore Young Jr. (July 31, 1921 – March 11, 1971) was an American civil rights leader. Trained as a social worker, he spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States and turning the National Urba ...

,

National Urban League

The National Urban League (NUL), formerly known as the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, is a nonpartisan historic civil rights organization based in New York City that advocates on behalf of economic and social justice for Afri ...

;

A. Philip Randolph,

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

Founded in 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids (commonly referred to as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, BSCP) was the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter in the American Federation o ...

;

John Lewis

John Robert Lewis (February 21, 1940 – July 17, 2020) was an American civil rights activist and politician who served in the United States House of Representatives for from 1987 until his death in 2020. He participated in the 1960 Nashville ...

,

SNCC

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and later, the Student National Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emer ...

; and

James L. Farmer Jr.,

Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about ...

.

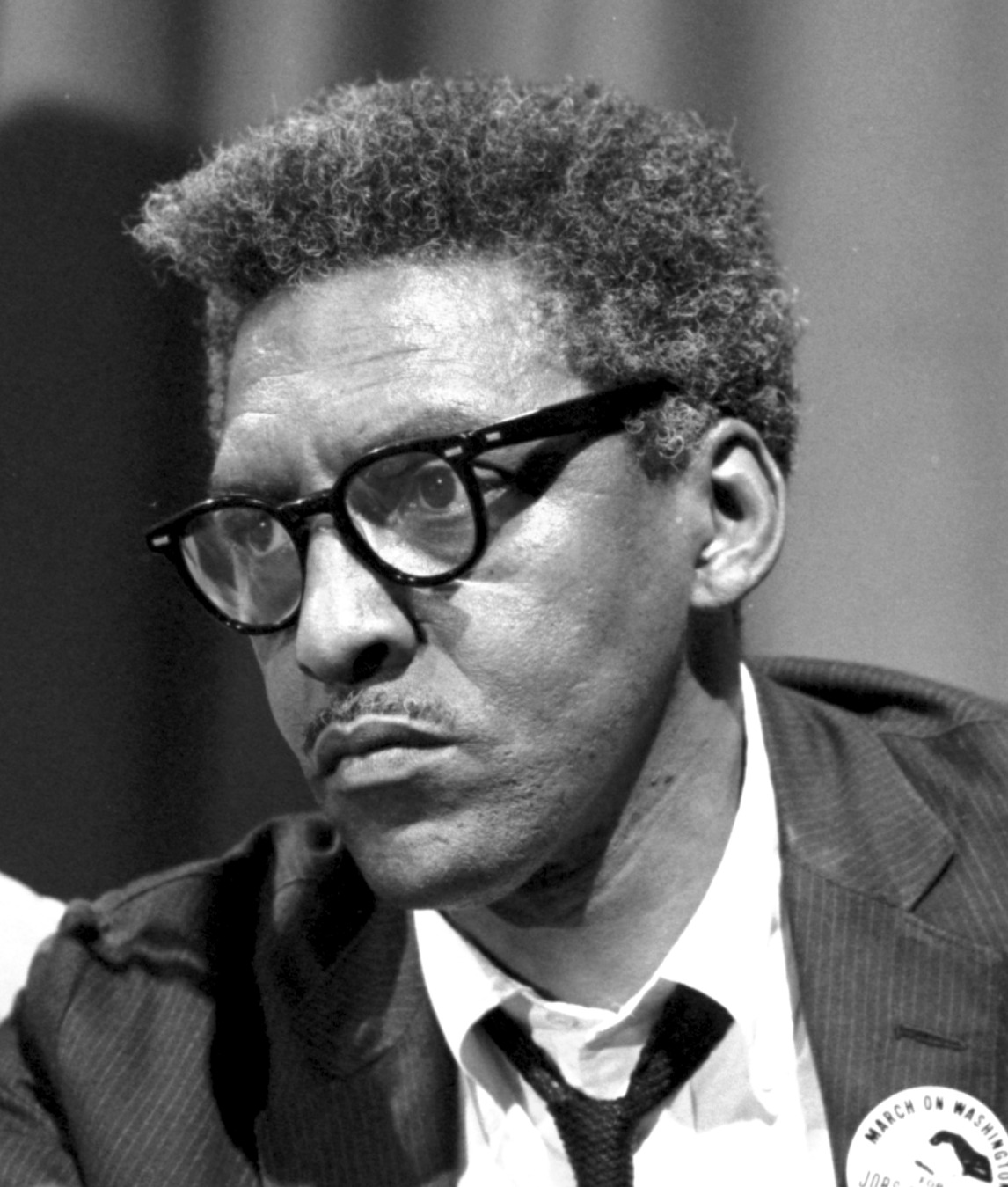

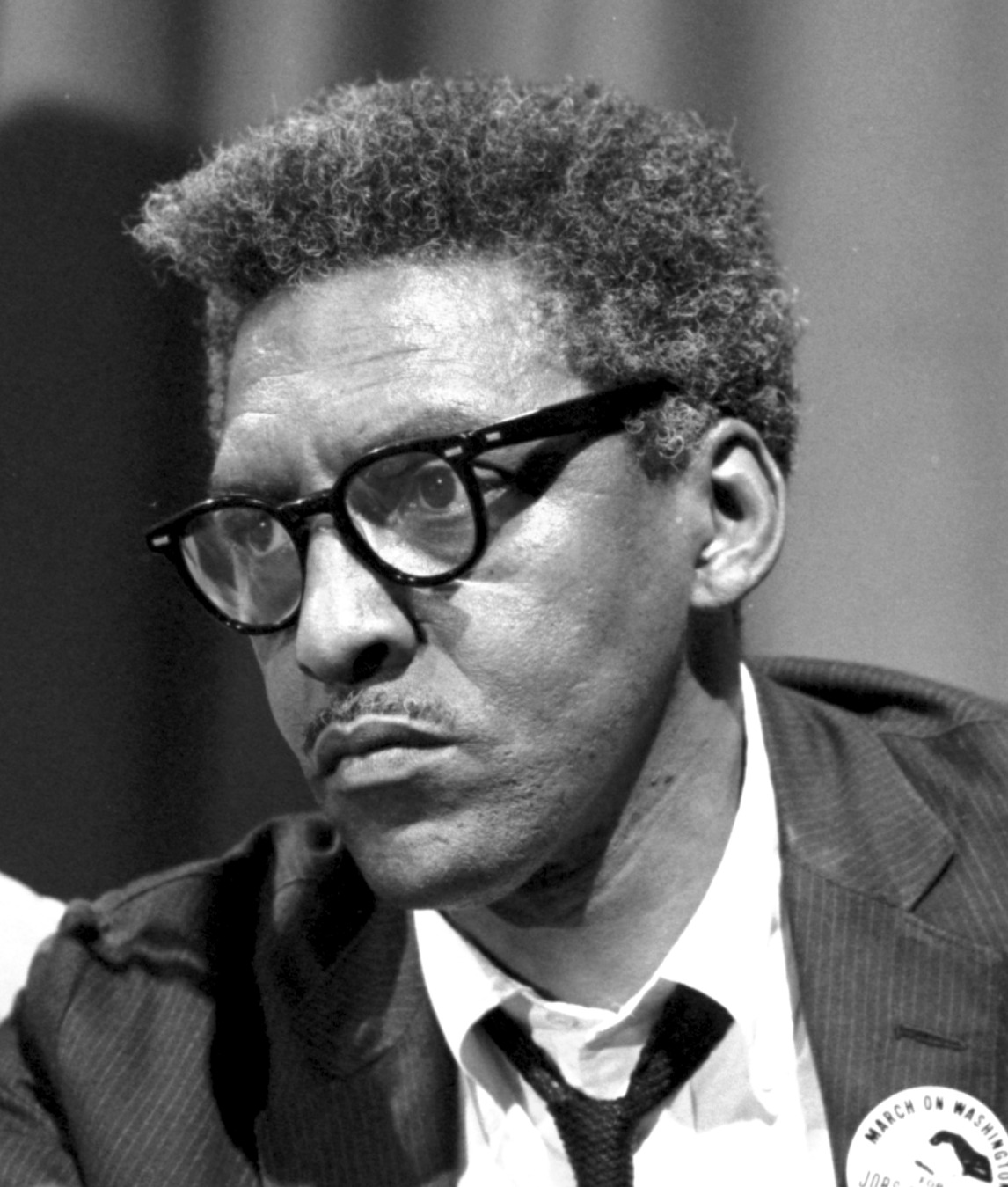

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin ( ; March 17, 1912 – August 24, 1987) was an American political activist and prominent leader in social movements for civil rights, socialism, nonviolence, and gay rights. Rustin was the principal organizer of the March on Wash ...

's open homosexuality, support of

socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, and former ties to the

Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

caused many white and African-American leaders to demand King distance himself, which King agreed to do. However, he did collaborate in the 1963 March on Washington, for which Rustin was the primary organizer. For King, this role was another which courted controversy, since he was a key figure who acceded to the wishes of President Kennedy in changing the focus of the march. Kennedy initially opposed the march outright, because he was concerned it would negatively impact the drive for passage of

civil rights legislation. However, the organizers were firm the march would proceed. With the march going forward, the Kennedys decided it was important to ensure its success. President Kennedy was concerned the turnout would be less than 100,000 and enlisted the aid of additional church leaders and

Walter Reuther

Walter Philip Reuther (; September 1, 1907 – May 9, 1970) was an American leader of organized labor and civil rights activist who built the United Automobile Workers (UAW) into one of the most progressive labor unions in American history. He ...

, president of the

United Automobile Workers

The United Auto Workers (UAW), fully named International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico) and sou ...

, to help mobilize demonstrators.

The march originally was planned to dramatize the desperate condition of blacks in the southern US and place organizers' concerns and grievances squarely before the seat of power in the capital. Organizers intended to denounce the federal government for its failure to safeguard the civil rights and physical safety of civil rights workers and blacks. The group acquiesced to presidential pressure, and the event ultimately took on a less strident tone.