Maria Graham on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Maria Graham, Lady Callcott (née Dundas; 19 July 1785 – 21 November 1842), was a British writer of

Maria Graham, Lady Callcott (née Dundas; 19 July 1785 – 21 November 1842), was a British writer of

In 1821, Graham was invited to accompany her husband aboard , a 36-gun frigate under his command. The destination was

In 1821, Graham was invited to accompany her husband aboard , a 36-gun frigate under his command. The destination was

/ref> This idea that the land could be lifted proved controversial, but correct. An extract of Maria's letter to

In recognition of her services to

In recognition of her services to

''Three months passed in the mountains East of Rome, during the Year 1819''

(1820) – translated into French 1822 **''Journal of a residence in Chile during the year 1822; and a voyage from Chile to Brazil in 1823'' (1824)

''Journal of a voyage to Brazil, and residence there, during part of the years 1821, 1822, 1823''

(1824) **''Voyage of the H.M.S. Blonde to the Sandwich Islands, in the years 1824-1825'' (1826) *As Maria Callcott or Lady Callcott:

''A short history of Spain''

(1828)

''Description of the chapel of the Annunziata dell'Arena; or, Giotto's chapel in Padua''

(1835)

''Little Arthur's history of England''

1835) **''Histoire de France du petit Louis'' (1836)

''Essays towards the history of painting''

(1836)

''The little bracken-burners, a tale; and Little Mary's four Saturdays''

(1841) **''A scripture herbal'' (1842)

''The Cherry Tree'' No. 2, 2004

published by the Cherry Tree Residents' Amenities Association in Kensington, London

''Journal of a Residence in Chile During the Year 1822''

at

Facsimile online version of ''Journal of a Voyage to Brazil'' – with her illustrations

Retrieved 27 January 2006 *

Paper by Dr. Martina Kölbl-Ebert about Maria Callcott's geological debacle

Retrieved 8 September 2008

''Little Arthur's history of England'' and other works by Maria Graham (Lady Callcott), Hathi Trust’s digital library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Graham, Maria 1785 births British children's writers British illustrators British travel writers History of Chile 1820s in Brazil 1842 deaths British women travel writers Wives of knights

Maria Graham, Lady Callcott (née Dundas; 19 July 1785 – 21 November 1842), was a British writer of

Maria Graham, Lady Callcott (née Dundas; 19 July 1785 – 21 November 1842), was a British writer of travel books

The genre of travel literature encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

One early travel memoirist in Western literature was Pausanias, a Greek geographer of the 2nd century CE. In the early modern period ...

and children's books

A child (plural, : children) is a human being between the stages of childbirth, birth and puberty, or between the Development of the human body, developmental period of infancy and puberty. The legal definition of ''child'' generally refers ...

, and also an accomplished illustrator.

Early life

She was born nearCockermouth

Cockermouth is a market town and civil parish in the Borough of Allerdale in Cumbria, England, so named because it is at the confluence of the River Cocker as it flows into the River Derwent. The mid-2010 census estimates state that Cocke ...

in Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

as Maria Dundas, and didn't see much of her father during her childhood and teenage years, as he was one of the many naval officers that the Scottish Dundas clan has raised through the years. George Dundas (1756–1814) (not to be confused with the much more famous naval officer George Heneage Lawrence Dundas

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

) was made post-captain

Post-captain is an obsolete alternative form of the rank of Captain (Royal Navy), captain in the Royal Navy.

The term served to distinguish those who were captains by rank from:

* Officers in command of a naval vessel, who were (and still are) ...

in 1795 and saw plenty of action as commander of HMS ''Juno'', a fifth-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a fifth rate was the second-smallest class of warships in a hierarchical system of six " ratings" based on size and firepower.

Rating

The rating system in the Royal N ...

32-gun frigate

A frigate () is a type of warship. In different eras, the roles and capabilities of ships classified as frigates have varied somewhat.

The name frigate in the 17th to early 18th centuries was given to any full-rigged ship built for speed and ...

, between 1798 and 1802. In 1803 he was given the command of , a 74-gun third-rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third r ...

that had been Nelson's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

during the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, and took her down to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

to patrol the Caribbean waters until 1806.

In 1808 his sea-fighting years were over, and he took an appointment as head of the naval works at the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

's dockyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance a ...

in Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

. When he went out to India he brought his now 23-year-old daughter along. During the long trip Maria Dundas fell in love with a young Scottish naval officer aboard, Thomas Graham, third son to Robert Graham, the last Laird

Laird () is the owner of a large, long-established Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a baron and above a gentleman. This rank was held only by those lairds holding official recognition in ...

of Fintry

Fintry is a small riverside village in Stirlingshire, central Scotland.

Landscape

The village of Fintry sits on the strath of the Endrick Water in a valley between the Campsie Fells and the Fintry Hills.

The name Fintry is said to have deri ...

. They married in India in 1809. In 1811, the young couple returned to England, where Graham published her first book, ''Journal of a Residence in India'', followed soon afterwards by ''Letters on India''. A few years later her father was appointed commissioner of the naval dockyard in Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

, where he died in 1814, aged 58, having been promoted rear-admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarded ...

just two months earlier.

Widow in Chile

As all other naval officers' wives, Graham spent several years ashore, seldom seeing her husband. Most of these years she lived in London. But while other officers' wives spent their time with domestic chores, she worked as a translator and book editor. In 1819 she lived in Italy for a time, which resulted in the book ''Three Months Passed in the Mountains East of Rome, during the Year 1819''. Being very interested in the arts, she also wrote a book about the French baroque painterNicolas Poussin

Nicolas Poussin (, , ; June 1594 – 19 November 1665) was the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style, although he spent most of his working life in Rome. Most of his works were on religious and mythological subjects painted for a ...

, ''Memoirs of the Life of Nicholas Poussin'' (French first names were usually Anglicised in those days), in 1820.

In 1821, Graham was invited to accompany her husband aboard , a 36-gun frigate under his command. The destination was

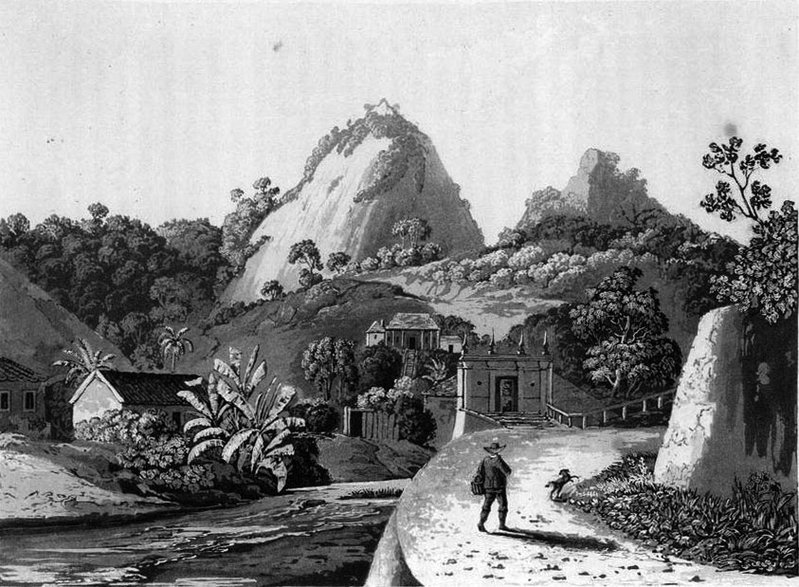

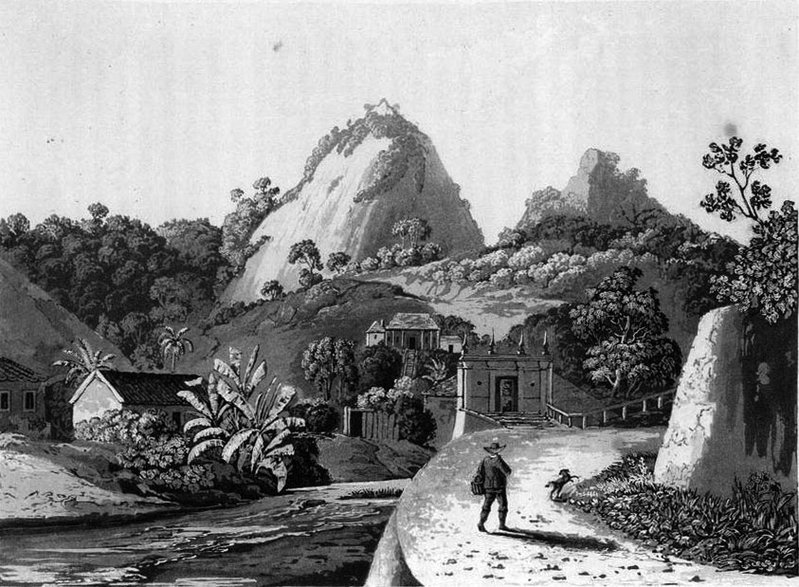

In 1821, Graham was invited to accompany her husband aboard , a 36-gun frigate under his command. The destination was Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, and the purpose was to protect British mercantile interests in the area. In April 1822, shortly after the ship had rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramírez ...

, her husband died of a fever, so HMS ''Doris'' arrived in Valparaiso without a captain, but with a distraught captain's widow. All the naval officers stationed in Valparaiso – British, Chilean and American – tried to help Maria (one American captain even offered to sail her back to Britain), but she was determined to manage on her own. She rented a small cottage, turned her back on the English colony ("I say nothing of the English here, because I do not know them except as very civil vulgar people, with one or two exceptions", she later wrote), and lived among the Chileans for a whole year. Later in 1822, she experienced one of the Valparaíso earthquake; one of the worst in Chile's history, and recorded its effects in detail. In her journal she recorded that after the earthquake "...the whole shore is more exposed and the rocks are about four feet higher out of the water than before."Maria Graham's 'Journal of a residence in Chile, during the year 1822; and a voyage from Chile to Brazil, in 1823', London, 1824/ref> This idea that the land could be lifted proved controversial, but correct. An extract of Maria's letter to

Henry Warburton

Henry Warburton (12 November 1784 – 16 September 1858) was an English merchant and politician, and also an enthusiastic amateur scientist.

Elected as Member of Parliament for Bridport, Dorset, in the 1826 general election, he held the seat fo ...

giving an account of the earthquake was published in 1824 in the Transactions of the Geological Society of London. This was the first paper published in this journal by a woman.

Tutor to the princess

In 1823, she began her journey back to Britain. She made a stop inBrazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

and was introduced to the newly appointed Brazilian emperor and his family. The year before, the Brazilians had declared independence from Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and had asked the resident Portuguese crown prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title is crown princess, which may refer either to an heiress apparent or, especially in earlier times, to the wif ...

to become their emperor. It was agreed that Graham should become the tutor of the young Princess Maria da Gloria, so when she reached London, she just handed over the manuscripts of her two new books to her publisher (''Journal of a Residence in Chile during the Year 1822. And a Voyage from Chile to Brazil in 1823'' and ''Journal of a Voyage to Brazil, and Residence There, During Part of the Years 1821, 1822, 1823'', illustrated by herself), collected suitable educational material, and returned to Brazil in 1824. She stayed in the royal palace only until October of that year, when she was asked to leave due to courtiers' suspicion of her motives and methods (courtiers seem to have feared, with some justice, that she intended to Anglicize the princess). During her few months with the royal family, she developed a close friendship with the empress, Maria Leopoldina of Austria

Dona Maria Leopoldina of Austria (22 January 1797 – 11 December 1826) was the first Empress of Brazil as the wife of Emperor Dom Pedro I from 12 October 1822 until her death. She was also Queen of Portugal during her husband's brief r ...

, who passionately shared her interests in the natural sciences. After leaving the palace, Graham experienced further difficulties in arranging for her transport home; unwillingly, she remained in Brazil until 1825, when she finally managed to arrange a passport and passage to England. Her treatment by palace courtiers left her with ambivalent feelings about Brazil and its government; she later recorded her version of events in her unpublished manuscript "Memoir of the Life of Don Pedro".

In March 1826, King John VI of Portugal

, house = Braganza

, father = Peter III of Portugal

, mother = Maria I of Portugal

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Queluz Palace, Queluz, Portugal

, death_date =

, death_place = Bemposta Palace, Lisbon, Portugal

, ...

died. His son Pedro inherited the throne, but preferred to remain Emperor of Brazil and thus abdicated the Portuguese throne in favour of his six-year-old daughter within two months.

Book about HMS ''Blondes famous journey

After her return from Brazil in 1825, her publisher John Murray asked her to write a book about the famous and recently completed voyage of HMS ''Blonde'' to the Sandwich Islands (asHawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

was then known). King Kamehameha II

Kamehameha II (November 1797 – July 14, 1824) was the second king of the Kingdom of Hawaii. His birth name was Liholiho and full name was Kalaninui kua Liholiho i ke kapu ʻIolani. It was lengthened to Kalani Kaleiʻaimoku o Kaiwikapu o Laʻ ...

and Queen Kamamalu of Hawaii had been on a visit to London in 1824 when they both died of the measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, against which they had no immunity. HMS ''Blonde'' was commissioned by the British Government to return their bodies to the Kingdom of Hawai'i

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi ( Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent islan ...

, with George Anson Byron in command, a cousin of poet Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

. The resulting book ''Voyage of the H.M.S. Blonde to the Sandwich Islands, In The Years 1824–1825'' contained a history of the royal couple's unfortunate visit to London, a résumé of the discovery of the Hawaiian Islands and visits by British explorers, as well as the story about ''Blondes journey. Her book remains a primary source for the voyage and includes an account of the funeral ceremony for the monarchs of the Kingdom of Hawai'i

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi ( Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent islan ...

. Graham wrote it with the help of official papers and journals kept by the ship's chaplain R. Rowland Bloxam; there is also a short section based on the records of naturalist Andrew Bloxam

Andrew Bloxam (22 September 1801 – 2 February 1878) was an English clergyman and naturalist; in his later life he had a particular interest in botany. He was the naturalist on board during its voyage around South America and the Pacific in 18 ...

.

Second marriage

When she arrived inLondon

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, Graham had taken rooms in Kensington Gravel Pits, just south of Notting Hill Gate

Notting Hill Gate is one of the main thoroughfares of Notting Hill, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Historically the street was a location for toll gates, from which it derives its modern name.

Location

At Ossington Street/Ke ...

, which was something of an artists' enclave, where Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

painter Augustus Wall Callcott

Sir Augustus Wall Callcott (20 February 177925 November 1844) was an English landscape painter.

Life and work

Callcott was born at Kensington Gravel Pits, a village on the western edge of London, in the area now known as Notting Hill Gate. ...

and his musician brother John Wall Callcott

John Wall Callcott (20 November 1766 – 15 May 1821) was an eminent English composer.

Callcott was born in Kensington, London. He was a pupil of Haydn, and is celebrated mainly for his glee compositions and catches. In the best known of his ...

lived, among with painters like John Linnell

John Sidney Linnell ( ; born June 12, 1959) is an American musician, known primarily as one half of the Brooklyn-based alternative rock band They Might Be Giants with John Flansburgh, which was formed in 1982. In addition to singing and songwri ...

, David Wilkie David Wilkie may refer to:

* David Wilkie (artist) (1785–1841), Scottish painter

* David Wilkie (surgeon) (1882–1938), British surgeon, scientist and philanthropist

* David Wilkie (footballer) (1914–2011), Australian rules footballer

* David ...

and William Mulready

William Mulready (1 April 1786 – 7 July 1863) was an Irish genre painter living in London. He is best known for his romanticising depictions of rural scenes, and for creating Mulready stationery letter sheets, issued at the same time as the P ...

, and musicians including William Crotch

William Crotch (5 July 177529 December 1847) was an English composer and organist. According to the American musicologist Nicholas Temperley, Crotchwas "a child prodigy without parallel in the history of music", and was certainly the most disti ...

(the first principal of the Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music (RAM) in London, England, is the oldest conservatoire in the UK, founded in 1822 by John Fane and Nicolas-Charles Bochsa. It received its royal charter in 1830 from King George IV with the support of the first Duke of ...

) and William Horsley

William Horsley (18 November 177412 June 1858) was an English musician. His compositions were numerous, and include amongst other instrumental pieces three Symphony, symphonies for full orchestra. More important are his Glee (music), glees, o ...

(John Callcott's son-in-law). In addition, this close-knit group was frequently visited by artists like John Varley, Edwin Landseer

Sir Edwin Henry Landseer (7 March 1802 – 1 October 1873) was an English painter and sculptor, well known for his paintings of animals – particularly horses, dogs, and stags. However, his best-known works are the lion sculptures at the bas ...

, John Constable

John Constable (; 11 June 1776 – 31 March 1837) was an English landscape painter in the Romanticism, Romantic tradition. Born in Suffolk, he is known principally for revolutionising the genre of landscape painting with his pictures of Dedha ...

and J.M.W. Turner

Joseph Mallord William Turner (23 April 177519 December 1851), known in his time as William Turner, was an English Romantic painter, printmaker and watercolourist. He is known for his expressive colouring, imaginative landscapes and turbule ...

.

Graham's lodgings very quickly became a focal point for London's intellectuals, such as the Scottish poet Thomas Campbell Thomas Campbell may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Thomas Campbell (poet) (1777–1844), Scottish poet

* Thomas Campbell (sculptor) (1790–1858), Scottish sculptor

* Thomas Campbell (visual artist) (born 1969), California-based visual artist ...

, Graham's book publisher John Murray and the historian Francis Palgrave

Sir Francis Palgrave, (; born Francis Ephraim Cohen, July 1788 – 6 July 1861) was an English archivist and historian. He was Deputy Keeper (chief executive) of the Public Record Office from its foundation in 1838 until his death; and he is ...

, but her keen interest and knowledge of painting (she was a skilled illustrator of her own books, and had written the book about Poussin) made it inevitable that she would quickly become part of the artists' enclave, as well.

Graham and Callcott married on his 48th birthday, 20 February 1827. In May of that year, the Callcotts embarked upon a year-long honeymoon

A honeymoon is a vacation taken by newlyweds immediately after their wedding, to celebrate their marriage. Today, honeymoons are often celebrated in destinations considered exotic or romantic. In a similar context, it may also refer to the phase ...

to Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, where they studied the art and architecture of those countries exhaustively and met many of the leading art critics, writers and connoisseurs of the time.

Disability

In 1831, Maria Callcott ruptured a blood vessel and becamephysically disabled

A physical disability is a limitation on a person's physical functioning, mobility, dexterity or stamina. Other physical disabilities include impairments which limit other facets of daily living, such as respiratory disorders, blindness, epilepsy ...

.

She could no longer travel, but she could continue to entertain her friends, and could continue her writing.

In 1828, immediately after returning from their honeymoon, she had published ''A Short History of Spain'', and in 1835 the writings during her long convalescence resulted in the publication of two books; ''Description of the chapel of the Annunziata dell’Arena; or Giotto’s Chapel in Padua'', and her first and most famous book for children, ''Little Arthur’s History of England'', which has been reprinted numerous times since then (already in 1851 the 16th edition was published, and it was last reprinted in 1975). ''Little Arthur'' was followed in 1836 by a French version; ''Histoire de France du petit Louis''.

Geological debate

In the mid-1830s her description of the earthquake in Chile of 1822 started a heated debate in the Geological Society, where she was caught in the middle of a fight between two rivalling schools of thought regarding earthquakes and their role in mountain building. Besides describing the earthquake in her ''Journal of a Residence in Chile'', she had also written about it in more detail in a letter toHenry Warburton

Henry Warburton (12 November 1784 – 16 September 1858) was an English merchant and politician, and also an enthusiastic amateur scientist.

Elected as Member of Parliament for Bridport, Dorset, in the 1826 general election, he held the seat fo ...

, who was one of the Geological Society

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

's founding fathers. As this was one of the first detailed eyewitness accounts by "a learned person" of an earthquake, he found it interesting enough to publish in ''Transactions of the Geological Society of London'' in 1823.

One of her observations had been that of large areas of land rising from the sea, and in 1830 that observation was included in the groundbreaking work ''The Principles of Geology'' by the geologist Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

, as evidence in support of his theory that mountains were formed by volcanoes and earthquakes. Four years later the president of the Society, George Bellas Greenough

George Bellas Greenough FRS FGS (18 January 1778 – 2 April 1855) was a pioneering English geologist. He is best known as a synthesizer of geology rather than as an original researcher.

Trained as a lawyer, he was a talented speaker and his ...

, decided to attack Lyell's theories. But instead of attacking Lyell directly, he did it by publicly ridiculing Maria Callcott's observations.

Maria Callcott, however, was not someone who accepted ridicule. Her husband and her brother offered to duel Greenough, but she said, according to her nephew John Callcott Horsley

John Callcott Horsley RA (29 January 1817 – 18 October 1903) was an English academic painter of genre and historical scenes, illustrator, and designer of the first Christmas card. He was a member of the artist's colony in Cranbrook.

Child ...

, "Be quiet, both of you, I am quite capable of fighting my own battles, and intend to do it". She went on to publish a crushing reply to Greenough, and was shortly thereafter backed by none other than Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

, who had observed the same land rising during Chile's earthquake in 1835, aboard the ''Beagle''.

In 1837 Augustus Callcott was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed and his wife became known as Lady Callcott. Shortly afterwards her health began to deteriorate, and in 1842 she died aged 57. She continued to write until the very end, and her last book was ''A Scripture Herbal'', an illustrated collection of tidbits and anecdotes about plants and trees mentioned in the Bible, which was published the same year she died.

Augustus Callcott died two years later, at the age of 65, having been made Surveyor of the Queen's Pictures

The office of the Surveyor of the King's/Queen's Pictures, in the Royal Collection Department of the Royal Household of the Monarch, Sovereign of the United Kingdom, is responsible for the care and maintenance of the royal collection of pictures ...

in 1843.

Honoured in 2008

In recognition of her services to

In recognition of her services to Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, as being one of the first persons to write about the young nation in the English language, the Chilean government

Chile's government is a representative democratic republic, whereby the President of Chile is both head of state and head of government, and of a formal multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the president and by their cabinet. Leg ...

paid for the restoration of Maria and Augustus Callcott's joint grave in Kensal Green Cemetery

Kensal Green Cemetery is a cemetery in the Kensal Green area of Queens Park in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in London, England. Inspired by Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, it was founded by the barrister George Frederic ...

in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

in 2008.

The restoration was finalised with a commemorative plaque

A commemorative plaque, or simply plaque, or in other places referred to as a historical marker, historic marker, or historic plaque, is a plate of metal, ceramic, stone, wood, or other material, typically attached to a wall, stone, or other ...

, unveiled by the Chilean ambassador

An ambassador is an official envoy, especially a high-ranking diplomat who represents a state and is usually accredited to another sovereign state or to an international organization as the resident representative of their own government or sov ...

to the United Kingdom, Rafael Moreno, at a ceremony on 4 September 2008. The plaque names Maria Callcott "a friend of the nation of Chile".

Works

*As Maria Graham: **''Journal of a residence in India'' (1812) – translated into French 1818 **''Memoirs of the war of the French in Spain'' (by Albert Jean Rocca) – translation from French (1816) **''Letters on India, with etchings and a map'' (1814) **''Memoir of the life of Nicolas Poussin'' (1820) – translated into French 1821 (Mémoires sur la vie de Nicolas Poussin)''Three months passed in the mountains East of Rome, during the Year 1819''

(1820) – translated into French 1822 **''Journal of a residence in Chile during the year 1822; and a voyage from Chile to Brazil in 1823'' (1824)

''Journal of a voyage to Brazil, and residence there, during part of the years 1821, 1822, 1823''

(1824) **''Voyage of the H.M.S. Blonde to the Sandwich Islands, in the years 1824-1825'' (1826) *As Maria Callcott or Lady Callcott:

''A short history of Spain''

(1828)

''Description of the chapel of the Annunziata dell'Arena; or, Giotto's chapel in Padua''

(1835)

''Little Arthur's history of England''

1835) **''Histoire de France du petit Louis'' (1836)

''Essays towards the history of painting''

(1836)

''The little bracken-burners, a tale; and Little Mary's four Saturdays''

(1841) **''A scripture herbal'' (1842)

Sources

*''Recollections of a Royal Academician'' by John Callcott Horsley. 1903''The Cherry Tree'' No. 2, 2004

published by the Cherry Tree Residents' Amenities Association in Kensington, London

Notes

References

External links

* *''Journal of a Residence in Chile During the Year 1822''

at

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

Facsimile online version of ''Journal of a Voyage to Brazil'' – with her illustrations

Retrieved 27 January 2006 *

Paper by Dr. Martina Kölbl-Ebert about Maria Callcott's geological debacle

Retrieved 8 September 2008

''Little Arthur's history of England'' and other works by Maria Graham (Lady Callcott), Hathi Trust’s digital library

{{DEFAULTSORT:Graham, Maria 1785 births British children's writers British illustrators British travel writers History of Chile 1820s in Brazil 1842 deaths British women travel writers Wives of knights