Margaret Mitchell (portrait) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Margaret Munnerlyn Mitchell (November 8, 1900 – August 16, 1949) was an American novelist and journalist. Mitchell wrote only one novel, published during her lifetime, the

The ''

The ''

A few years after the riot, the Mitchell family decided to move away from Jackson Hill. In 1912, they moved to the east side of Peachtree Street just north of Seventeenth Street in Atlanta. Past the nearest neighbor's house was forest and beyond it the

A few years after the riot, the Mitchell family decided to move away from Jackson Hill. In 1912, they moved to the east side of Peachtree Street just north of Seventeenth Street in Atlanta. Past the nearest neighbor's house was forest and beyond it the

During

During

Margaret Mitchell was struck by a speeding motorist as she crossed

Margaret Mitchell was struck by a speeding motorist as she crossed

(August 17, 1949) ''New York Times''. Retrieved May 14, 2011. Gravitt was originally charged with drunken driving, speeding, and driving on the wrong side of the road. He was convicted of involuntary manslaughter in November 1949 and sentenced to 18 months in jail. He served almost 11 months. Gravitt died in 1994 at the age of 74. Margaret Mitchell was buried at Oakland Cemetery,

Lost In Yesterday: Commemorating The 70th Anniversary of Margaret Mitchell's 'Gone With The Wind'

'. Marietta, Georgia: First Works Publishing Co., Inc., 2006. . * Brown, Ellen F. and John Wiley. ''Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind: A Bestseller's Odyssey from Atlanta to Hollywood''. Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade, 2011. . * Edwards, Anne. ''Road to Tara: The Life of Margaret Mitchell''. New Haven: Tichnor and Fields, 1983. * Farr, Finis. ''Margaret Mitchell of Atlanta: The Author of Gone With the Wind''. New York: William Morrow, 1965. * Mitchell, Margaret, Allen Barnett Edee and Jane Bonner Peacock. ''A Dynamo Going to Waste: Letters to Allen Edee, 1919–1921''. Atlanta, Georgia: Peachtree Publishers, Ltd, 1985. * Mitchell, Margaret and Patrick Allen. ''Margaret Mitchell: Reporter''. Athens, Georgia: Hill Street Press, 2000. * Mitchell, Margaret and Jane Eskridge. ''Before Scarlett: Girlhood Writings of Margaret Mitchell''. Athens, Georgia: Hill Street Press, 2000. * Pyron, Darden Asbury. ''Southern Daughter: The Life of Margaret Mitchell''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. * Walker, Marianne. ''Margaret Mitchell & John Marsh: The Love Story Behind Gone With the Wind''. Atlanta: Peachtree, 1993.

Margaret Mitchell

entry at New Georgia Encyclopedia

Margaret Mitchell: American Rebel

– American Masters documentary (PBS)

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991

The Magaret Mitchell interview from ''Yank Magazine'' (1945)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mitchell, Margaret 1900 births 1949 deaths 20th-century American novelists 20th-century American women writers American debutantes American historical novelists American manslaughter victims American people of Irish descent American people of Scottish descent American romantic fiction writers American women novelists Burials at Oakland Cemetery (Atlanta) Converts to Anglicanism from Roman Catholicism National Book Award winners Pedestrian road incident deaths Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners Road incident deaths in Georgia (U.S. state) Smith College alumni The Atlanta Journal-Constitution people Writers from Atlanta People from Jonesboro, Georgia Writers of American Southern literature Women historical novelists Women romantic fiction writers

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

-era novel ''Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* Gone with the Wind (novel), ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* Gone with the Wind (film), ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Win ...

'', for which she won the National Book Award for Fiction

The National Book Award for Fiction is one of five annual National Book Awards, which recognize outstanding literary work by United States citizens. Since 1987 the awards have been administered and presented by the National Book Foundation, but ...

for Most Distinguished Novel of 1936 and the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published during ...

in 1937. Long after her death, a collection of Mitchell's girlhood writings and a novella she wrote as a teenager, titled ''Lost Laysen

''Lost Laysen'' is a novella by Margaret Mitchell. Although it was written in 1916, it was not published until 1996.

Mitchell, who is best known as the author of ''Gone with the Wind'', was believed to have only written one full book during her l ...

'', were published. A collection of newspaper articles written by Mitchell for ''The Atlanta Journal'' was republished in book form.

Family history

Margaret Mitchell was a Southerner, a native and lifelong resident ofGeorgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. She was born in 1900 into a wealthy and politically prominent family. Her father, Eugene Muse Mitchell, was an attorney, and her mother, Mary Isabel "Maybelle" Stephens, was a suffragist

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

activist. She had two brothers, Russell Stephens Mitchell, who died in infancy in 1894, and Alexander Stephens Mitchell, born in 1896.

Mitchell's family on her father's side were descendants of Thomas Mitchell, originally of Aberdeenshire

Aberdeenshire ( sco, Aiberdeenshire; gd, Siorrachd Obar Dheathain) is one of the 32 Subdivisions of Scotland#council areas of Scotland, council areas of Scotland.

It takes its name from the County of Aberdeen which has substantially differe ...

, Scotland, who settled in Wilkes County, Georgia

Wilkes County is a county located in the east central portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 10,593. The county seat is the city of Washington.

Referred to as "Washington-Wilkes", the county seat and co ...

in 1777, and served in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Thomas Mitchell was a surveyor by profession. He was on a surveying trip in Henry County, Georgia

Henry County is located in the north central portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. Per the 2020 census, the population of Henry County is 240,712, up from 203,922 in 2010. The county seat is McDonough. The county was named for Patrick Henry.

He ...

, at the home of Mr. John Lowe, about 6 miles from McDonough, Georgia

McDonough is a city in Henry County, Georgia, United States. It is part of the Atlanta metropolitan area. Its population was 22,084 at the 2010 census, up from 8,493 in 2000. The city is the county seat of Henry County. The unincorporated comm ...

, when he died in 1835 and is buried in that location. William Mitchell, born December 8, 1777, in Lisborn, Edgefield County

Edgefield County is a County (United States), county located on the western border of the U.S. state of South Carolina. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, its population was 25,657. Its county seat and largest municipality is Edge ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, moved between 1834 and 1835, to a farm along the South River in the Flat Rock community in Georgia. William Mitchell died February 24, 1859, at the age of 81 and is buried in the family graveyard near Panola Mountain

Panola Mountain is a granite monadnock near Stockbridge on the boundary between Henry County and Rockdale County, Georgia. The peak is above sea level, rising above the South River. The South River marks the boundary between Henry, Rockdale ...

State Park. Her great-grandfather Issac Green Mitchell moved to farm along the Flat Shoals Road located in the Flat Rock community in 1839. Four years later he sold this farm to Ira O. McDaniel and purchased a farm 3 miles farther down the road on the north side of the South River in DeKalb County, Georgia

DeKalb County (, , ) is located in the north central portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 764,382, making it Georgia's fourth-most populous county. Its county seat is Decatur.

DeKalb County is inclu ...

.

Her grandfather, Russell Crawford Mitchell, of Atlanta, enlisted in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

on June 24, 1861, and served in Hood's Texas Brigade. He was severely wounded at the Battle of Sharpsburg

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, demoted for "inefficiency," and detailed as a nurse in Atlanta. After the Civil War, he made a large fortune supplying lumber for the rapid rebuilding of Atlanta. Russell Mitchell had thirteen children from two wives; the eldest was Eugene, who graduated from the University of Georgia Law School

The University of Georgia School of Law (Georgia Law) is the law school of the University of Georgia, a Public university, public research university in Athens, Georgia. It was founded in 1859, making it among the oldest American university law sc ...

.

Mitchell's maternal great-grandfather, Philip Fitzgerald, emigrated from Ireland and eventually settled on a slaveholding plantation, Rural Home

Rural Home, also known as the Fitzgerald House, was a plantation house in Clayton County, Georgia. Built in the 1830s, the house was acquired by Philip Fitzgerald, a planter and Irish immigrant, in 1836. Rural Home was the childhood home of Annie ...

, near Jonesboro, Georgia

Jonesboro is a city in and the county seat of Clayton County, Georgia, United States. The population was 4,724 as of the 2010 census.

The city's name was originally spelled Jonesborough. During the Civil War, the final skirmish in the Atlanta Cam ...

, where he had one son and seven daughters with his wife, Elenor McGahan, who was from an Irish Catholic family with ties to Colonial Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an English and later British colony in North America that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the Thirteen Colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and became the U.S. state of Maryland ...

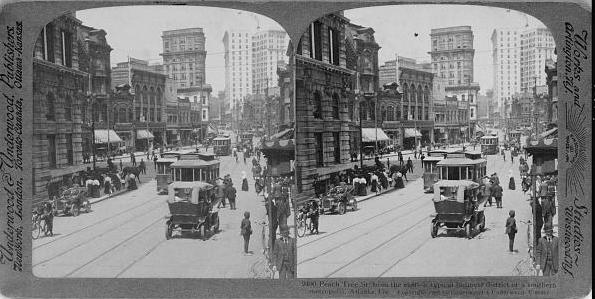

. Mitchell's grandparents, married in 1863, were Annie Fitzgerald and John Stephens; he had also emigrated from Ireland and became a captain in the Confederate States Army. John Stephens was a prosperous real estate developer after the Civil War and one of the founders of the Gate City Street Railroad The Gate City Street Railroad Company of Atlanta, Georgia was chartered by the state of Georgia on September 26, 1879. The individuals involved in the formation of the company included Laurent DeGive (Belgian consul and opera house owner), Levi B. ...

(1881), a mule-drawn Atlanta trolley system. John and Annie Stephens had twelve children together; the seventh child was May Belle Stephens, who married Eugene Mitchell. May Belle Stephens had studied at the Bellevue Convent in Quebec and completed her education at the Atlanta Female Institute.

The ''

The ''Atlanta Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the only major daily newspaper in the Atlanta metropolitan area, metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Con ...

'' reported that May Belle Stephens and Eugene Mitchell were married at the Jackson Street mansion of the bride's parents on November 8, 1892:

the maid of honor, Miss Annie Stephens, was as pretty as a French pastel, in a directoire costume of yellow satin with a long coat of green velvet sleeves, and a vest of gold brocade...The bride was a fair vision of youthful loveliness in her robe of exquisite ivory white andsatin A satin weave is a type of fabric weave that produces a characteristically glossy, smooth or lustrous material, typically with a glossy top surface and a dull back. It is one of three fundamental types of textile weaves alongside plain weave ......her slippers were white satin wrought withpearl A pearl is a hard, glistening object produced within the soft tissue (specifically the mantle) of a living shelled mollusk or another animal, such as fossil conulariids. Just like the shell of a mollusk, a pearl is composed of calcium carb ...s...an elegant supper was served. The dining room was decked in white and green, illuminated with numberless candles in silver candlelabras...The bride's gift from her father was an elegant house and lot...At 11 o'clock Mrs. Mitchell donned a pretty going-away gown of green English cloth with its jaunty velvet hat to match and bid goodbye to her friends.

Early influences

Margaret Mitchell spent her early childhood on Jackson Hill, east ofdowntown Atlanta

Downtown Atlanta is the central business district of Atlanta, Georgia, United States. The larger of the city's two other commercial districts ( Midtown and Buckhead), it is the location of many corporate and regional headquarters; city, county, s ...

. Her family lived near her maternal grandmother, Annie Stephens, in a Victorian house

In Great Britain and former British colonies, a Victorian house generally means any house built during the reign of Queen Victoria. During the Industrial Revolution, successive housing booms resulted in the building of many millions of Victorian ...

painted bright red with yellow trim. Mrs. Stephens had been a widow for several years prior to Margaret's birth; Captain John Stephens died in 1896. After his death, she inherited property on Jackson Street where Margaret's family lived.

Grandmother Annie Stephens was quite a character, both vulgar and a tyrant. After gaining control of her father Philip Fitzgerald's money after he died, she splurged on her younger daughters, including Margaret's mother, and sent them to finishing school in the north. There they learned that Irish Americans were not treated as equal to other immigrants. Margaret's relationship with her grandmother would become quarrelsome in later years as she entered adulthood. However, for Margaret, her grandmother was a great source of "eye-witness information" about the Civil War and Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

in Atlanta prior to her death in 1934.

Girlhood on Jackson Hill

In an accident that was traumatic for her mother although she was unharmed, when Mitchell was about three years old, her dress caught fire on an iron grate. Fearing it would happen again, her mother began dressing her in boys' pants, and she was nicknamed "Jimmy", the name of a character in the comic strip, ''Little Jimmy

''Little Jimmy'', originally titled ''Jimmy'', is a newspaper comic strip created by Jimmy Swinnerton. With a publication history from February 14, 1904, to April 27, 1958, it was one of the first continuing features and one of the longest running ...

''.Jones, Anne Goodwyn. ''Tomorrow is Another Day: the woman writer in the South 1859–1936''. Baton Rouge, LA: University of Louisiana Press, 1981. p. 322. Her brother insisted she would have to be a boy named Jimmy to play with him. Having no sisters to play with, Mitchell said she was a boy named Jimmy until she was fourteen.

Stephens Mitchell said his sister was a tomboy

A tomboy is a term for a girl or a young woman with masculine qualities. It can include wearing androgynous or unfeminine clothing and actively engage in physical sports or other activities and behaviors usually associated with boys or men. W ...

who would happily play with dolls occasionally, and she liked to ride her Texas plains pony. As a little girl, Mitchell went riding every afternoon with a Confederate veteran and a young lady of "beau-age". She was raised in an era when children were "seen and not heard" and was not allowed to express her personality by running and screaming on Sunday afternoons while her family was visiting relatives.

Mitchell learned the gritty details of specific battles from these visits with aging Confederate soldiers. But she didn't learn that the South had actually lost the war until she was 10 years of age: "I heard everything in the world except that the Confederates lost the war. When I was ten years old, it was a violent shock to learn that General Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of North ...

had been defeated. I didn't believe it when I first heard it and I was indignant. I still find it hard to believe, so strong are childhood impressions." Her mother would swat her with a hairbrush or a slipper as a form of discipline.Farr, Finis, ''Margaret Mitchell of Atlanta: the author of Gone With the Wind'', p. 14.

May Belle Mitchell was "hissing blood-curdling threats" to her daughter to make her behave the evening she took her to a women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

rally led by Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (; January 9, 1859 Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt ...

. Her daughter sat on a platform wearing a Votes-for-Women banner, blowing kisses to the gentlemen, while her mother gave an impassioned speech. She was nineteen years old when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified, which gave women the right to vote.

May Belle Mitchell was president of the Atlanta Woman's Suffrage League (1915), co-founder of Georgia's division of the League of Women Voters

The League of Women Voters (LWV or the League) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization in the United States. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for vot ...

, chairwoman of press publicity for the Georgia Mothers' Congress and Parent Teacher Association

A parent is a caregiver of the offspring in their own species. In humans, a parent is the caretaker of a child (where "child" refers to offspring, not necessarily age). A ''biological parent'' is a person whose gamete resulted in a child, a male t ...

, a member of the Pioneer Society, the Atlanta Woman's Club

The Atlanta Woman’s Club is one of oldest non-profit woman’s organizations in Atlanta, organized November 11, 1895. It is a 501(c)3 non-profit philanthropic organization made up of professional women of all ages, races and religions.

The At ...

, and several Catholic and literary societies.

Mitchell's father was not in favor of corporal punishment in school. During his tenure as president of the educational board (1911–1912), corporal punishment in the public schools was abolished. Reportedly, Eugene Mitchell received a whipping on the first day he attended school and the mental impression of the thrashing lasted far longer than the physical marks.

Jackson Hill was an old, affluent part of the city.Bartley, Numen V. ''The Evolution of Southern Culture'', Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1988. p. 89. At the bottom of Jackson Hill was an area of African-American homes and businesses called "Darktown

Darktown was an African-American neighborhood in Atlanta, Georgia. It stretched from Peachtree Street and Collins Street (now Courtland Street), past Butler Ave. (now Jesse Hill Jr. Ave.) to Jackson Street. It referred to the blocks above Auburn Av ...

". The mayhem of the Atlanta Race Riot

Violent attacks by armed mobs of White Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, began on the evening of September 22, 1906, and lasted through September 24, 1906. The events were reported by newspapers around the world, includi ...

occurred over four days in September 1906 when Mitchell was five years old. Local white newspapers printed unfounded rumors that several white women had been assaulted by black men, prompting an angry mob of 10,000 to assemble in the streets, pulling black people from street cars, beating, killing dozens over the next three days.

Eugene Mitchell went to bed early the night the rioting began, but was awakened by the sounds of gunshots. The following morning, as he later wrote, to his wife, he learned "16 negroes had been killed and a multitude had been injured" and that rioters "killed or tried to kill every Negro they saw." As the rioting continued, rumors ran wild that black people would burn Jackson Hill.Hobson, Fred C. ''South to the future: an American region in the twenty-first century'', p. 19-21. At his daughter's suggestion, Eugene Mitchell, who did not own a gun, stood guard with a sword.

Though the rumors proved untrue and no attack arrived, Mitchell recalled twenty years later the terror she felt during the riot. Mitchell grew up in a Southern culture where the fear of black-on-white rape incited mob violence, and in this world, white Georgians lived in fear of the "black beast rapist".

A few years after the riot, the Mitchell family decided to move away from Jackson Hill. In 1912, they moved to the east side of Peachtree Street just north of Seventeenth Street in Atlanta. Past the nearest neighbor's house was forest and beyond it the

A few years after the riot, the Mitchell family decided to move away from Jackson Hill. In 1912, they moved to the east side of Peachtree Street just north of Seventeenth Street in Atlanta. Past the nearest neighbor's house was forest and beyond it the Chattahoochee River

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida - Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chatta ...

. Mitchell's former Jackson Hill home was destroyed in the Great Atlanta Fire of 1917

The Great Atlanta Fire of 1917 began just after noon on 21 May 1917 in the Old Fourth Ward of Atlanta, Georgia. It is unclear just how the fire started, but it was fueled by hot temperatures and strong winds which propelled the fire. The fire, ...

.

Mitchell's father was of a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

background, while her mother was a devout Catholic; Mitchell was raised in a Catholic household. As a young woman, she spent time visiting the Sisters of Mercy

The Sisters of Mercy is a religious institute of Catholic women founded in 1831 in Dublin, Ireland, by Catherine McAuley. As of 2019, the institute had about 6200 sisters worldwide, organized into a number of independent congregations. They a ...

convent affiliated with St. Joseph's Infirmary in downtown Atlanta. Her religious upbringing influenced her decision to make the O'Hara family in her novel Catholics in a Protestant-majority state. One of Mitchell's mother's cousins entered the Sisters of Mercy at St. Vincent's Convent in Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

in 1883, becoming Sister Mary Melanie. The characters Melanie Hamilton

Melanie Hamilton Wilkes is a fictional character first appearing in the 1936 novel ''Gone with the Wind'' by Margaret Mitchell. In the 1939 film she was portrayed by Olivia de Havilland. Melanie is Scarlett O'Hara's sister-in-law and eventually ...

and Careen O'Hara were probably based on this relation.

The South of ''Gone with the Wind''

While "the South" exists as a geographical region of the United States, it is also said to exist as "a place of the imagination" of writers. An image of "the South" was fixed in Mitchell's imagination when at six years old her mother took her on a buggy tour through ruined plantations and "Sherman's sentinels", the brick and stone chimneys that remained afterWilliam Tecumseh Sherman

William Tecumseh Sherman ( ; February 8, 1820February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–1865), achieving recognition for his com ...

's "March

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. It is the second of seven months to have a length of 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of Marc ...

and torch" through Georgia. Mitchell would later recall what her mother had said to her:

She talked about the world those people had lived in, such a secure world, and how it had exploded beneath them. And she told me that my world was going to explode under me, someday, and God help me if I didn't have some weapon to meet the new world.Felder, Deborah G. ''A Century of Women: the most influential events in twentieth-century women's history''. New York, NY: Citadel Press, 1999. p. 158.From an imagination cultivated in her youth, Margaret Mitchell's defensive weapon would become her writing. Mitchell said she heard Civil War stories from her relatives when she was growing up:

On Sunday afternoons when we went calling on the older generation of relatives, those who had been active in the Sixties, I sat on the bony knees of veterans and the fat slippery laps of great aunts and heard them talk.On summer vacations, she visited her maternal great-aunts, Mary Ellen ("Mamie") Fitzgerald and Sarah ("Sis") Fitzgerald, who still lived at her great-grandparents' plantation home in Jonesboro. Mamie had been twenty-one years old and Sis was thirteen when the Civil War began.

An avid reader

An avid reader, young Margaret read "boys' stories" byG.A. Henty

George Alfred Henty (8 December 1832 – 16 November 1902) was an English novelist and war correspondent. He is most well-known for his works of adventure fiction and historical fiction, including ''The Dragon & The Raven'' (1886), ''For The ...

, the Tom Swift

Tom Swift is the main character of six series of American juvenile science fiction and adventure novels that emphasize science, invention, and technology. First published in 1910, the series totals more than 100 volumes. The character was ...

series, and the Rover Boys

The Rover Boys, or The Rover Boys Series for Young Americans, was a popular juvenile series written by Arthur M. Winfield, a pseudonym for Edward Stratemeyer. Thirty titles were published between 1899 and 1926 and the books remained in print for ...

series by Edward Stratemeyer

Edward L. Stratemeyer (; October 4, 1862 – May 10, 1930) was an American publisher, writer of children's fiction, and founder of the Stratemeyer Syndicate. He was one of the most prolific writers in the world, producing in excess of 1,300 ...

. Her mother read Mary Johnston

Mary Johnston (November 21, 1870 – May 9, 1936) was an American novelist and women's rights advocate from Virginia. She was one of America's best selling authors during her writing career and had three silent films adapted from her novels. Jo ...

's novels to her before she could read. They both wept reading Johnston's ''The Long Roll'' (1911) and ''Cease Firing'' (1912). Between the "scream of shells, the mighty onrush of charges, the grim and grisly aftermath of war", ''Cease Firing'' is a romance novel involving the courtship of a Confederate soldier and a Louisiana plantation belle with Civil War illustrations by N. C. Wyeth

Newell Convers Wyeth (October 22, 1882 – October 19, 1945), known as N. C. Wyeth, was an American painter and illustrator. He was the pupil of Howard Pyle and became one of America's most well-known illustrators. Wyeth created more than 3,000 ...

. She also read the plays of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, and novels by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

and Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy' ...

.Champion, Laurie. ''American Women Writers, 1900–1945: a bio-bibliographical critical sourcebook''. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000. p. 240. Mitchell's two favorite children's books were by author Edith Nesbit

Edith Nesbit (married name Edith Bland; 15 August 1858 – 4 May 1924) was an English writer and poet, who published her children's literature, books for children as E. Nesbit. She wrote or collaborated on more than 60 such books. She was also ...

: ''Five Children and It

''Five Children and It'' is a children's novel by English author E. Nesbit. It was originally published in 1902 in the '' Strand Magazine'' under the general title ''The Psammead, or the Gifts'', with a segment appearing each month from April ...

'' (1902) and ''The Phoenix and the Carpet

''The Phoenix and the Carpet'' is a fantasy novel for children, written by E. Nesbit and first published in 1904. It is the second in a trilogy of novels that begins with ''Five Children and It'' (1902), and follows the adventures of the same ...

'' (1904). She kept both on her bookshelf even as an adult and gave them as gifts. Another author whom Mitchell read as a teenager and who had a major impact in her understanding of the Civil War and Reconstruction was Thomas Dixon. Dixon's popular trilogy of novels '' The Leopard's Spots: A Romance of the White Man's Burden'' (1902), '' The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan'' (1905) and '' The Traitor: A Story of the Rise and Fall of the Invisible Empire'' (1907) all depicted in vivid terms a white South victimized during the Reconstruction by Northern carpetbaggers

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the lo ...

and freed slaves, with an especial emphasis upon Reconstruction as a nightmarish time when black men ran amok, raping white women with impunity. As a teenager, Mitchell liked Dixon's books so much that she organized the local children to put on dramatizations of his books. The picture the white supremacist Dixon drew of Reconstruction is now rejected as inaccurate, but at the time, the memory of the past was such it was widely believed by white Americans. In a letter to Dixon dated August 10, 1936, Mitchell wrote: "I was practically raised on your books, and love them very much."

Young storyteller

An imaginative and precocious writer, Margaret Mitchell began with stories about animals, then progressed to fairy tales and adventure stories. She fashioned book covers for her stories, bound the tablet paper pages together and added her own artwork. At age eleven she gave a name to her publishing enterprise: "Urchin Publishing Co." Later her stories were written in notebooks. Mary Belle Mitchell kept her daughter's stories in white enamel bread boxes and several boxes of her stories were stored in the house by the time Margaret went off to college. "Margaret" is a character riding a galloping pony in ''The Little Pioneers'', and plays " Cowboys and Indians" in ''When We Were Shipwrecked''. Romantic love and honor emerged as themes of abiding interest for Mitchell in ''The Knight and the Lady'' (ca. 1909), in which a "goodknight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

" and a "bad knight" duel for the hand of the lady. In ''The Arrow Brave and the Deer Maiden'' (ca. 1913), a half-white Indian brave, Jack, must withstand the pain inflicted upon him to uphold his honor and win the girl. The same themes were treated with increasing artistry in ''Lost Laysen'', the novella Mitchell wrote as a teenager in 1916, and, with much greater sophistication, in Mitchell's last known novel, ''Gone with the Wind'', which she began in 1926.

In her pre-teens, Mitchell also wrote stories set in foreign locations, such as ''The Greaser'' (1913), a cowboy

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the '' vaquer ...

story set in Mexico. In 1913 she wrote two stories with Civil War settings; one includes her notation that "237 pages are in this book".

School life

While theGreat War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

carried on in Europe (1914–1918), Margaret Mitchell attended Atlanta's Washington Seminary (now The Westminster Schools

The Westminster Schools is a Kindergarten –12 private school in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, founded in 1951.

History

Westminster originated in 1951 as a reorganization of Atlanta's North Avenue Presbyterian School (NAPS), a girls' school a ...

), a "fashionable" private girls' school with an enrollment of over 300 students. She was very active in the Drama Club. Mitchell played the male characters: Nick Bottom

Nick Bottom is a character in Shakespeare's ''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' who provides comic relief throughout the play. A weaver by trade, he is famously known for getting his head transformed into that of a donkey by the elusive Puck. Bott ...

in Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''A Midsummer Night's Dream

''A Midsummer Night's Dream'' is a comedy written by William Shakespeare 1595 or 1596. The play is set in Athens, and consists of several subplots that revolve around the marriage of Theseus and Hippolyta. One subplot involves a conflict amon ...

'' and Launcelot Gobbo in Shakespeare's ''The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'', among others. She wrote a play about snobbish college girls that she acted in as well. She also joined the Literary Club and had two stories published in the yearbook: ''Little Sister'' and ''Sergeant Terry''. Ten-year-old "Peggy" is the heroine in ''Little Sister''. She hears her older sister being raped and shoots the rapist:

Coldly, dispassionately she viewed him, the chill steel of the gun giving her confidence. She must not miss now—she would not miss—and she did not.Mitchell received encouragement from her English teacher, Mrs. Paisley, who recognized her writing talent. A demanding teacher, Paisley told her she had ability if she worked hard and would not be careless in constructing sentences. A sentence, she said, must be "complete, concise and coherent". Mitchell read the books of

Thomas Dixon, Jr.

Thomas Frederick Dixon Jr. (January 11, 1864 – April 3, 1946) was an American white supremacist, Baptist minister, politician, lawyer, lecturer, novelist, playwright, and filmmaker. Referred to as a "professional racist", Dixon wrote two best- ...

, and in 1916, when the silent film, ''The Birth of a Nation

''The Birth of a Nation'', originally called ''The Clansman'', is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play ''The Cla ...

'', was showing in Atlanta, she dramatized Dixon's ''The Traitor: A Story of the Fall of the Invisible Empire'' (1907). As both playwright and actress, she took the role of Steve Hoyle. For the production, she made a Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

costume from a white crepe dress and wore a boy's wig. (Note: Dixon rewrote ''The Traitor'' as ''The Black Hood'' (1924) and Steve Hoyle was renamed George Wilkes.)

During her years at Washington Seminary, Mitchell's brother, Stephens, was away studying at Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

(1915–1917), and he left in May 1917 to enlist in the army, about a month after the U.S. declared war on Germany. He set sail for France in April 1918, participated in engagements in the Lagny and Marbache sectors, then returned to Georgia in October as a training instructor. While Margaret and her mother were in New York in September 1918 preparing for Margaret to attend college, Stephens wired his father that he was safe after his ship had been torpedoed en route to New York from France.

Stephens Mitchell thought college was the "ruination of girls". However, May Belle Mitchell placed a high value on education for women and she wanted her daughter's future accomplishments to come from using her mind. She saw education as Margaret's weapon and "the key to survival". The classical college education she desired for her daughter was one that was on par with men's colleges, and this type of education was available only at northern schools. Her mother chose Smith College

Smith College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smith (Smith College ...

in Northampton, Massachusetts

The city of Northampton is the county seat of Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of Northampton (including its outer villages, Florence and Leeds) was 29,571.

Northampton is known as an acade ...

for Margaret because she considered it to be the best women's college in the United States.

Upon graduating from Washington Seminary in June 1918, Mitchell fell in love with a Harvard graduate, a young army lieutenant, Clifford West Henry, who was chief bayonet instructor at Camp Gordon

Fort Gordon, formerly known as Camp Gordon, is a United States Army installation established in October 1941. It is the current home of the United States Army Signal Corps, United States Army Cyber Command, and the Cyber Center of Excellence. It ...

from May 10 until the time he set sail for France on July 17. Henry was "slightly effeminate", "ineffectual", and "rather effete-looking" with "homosexual tendencies", according to biographer Anne Edwards

Anne Edwards (born August 20, 1927) is an American writer best known for her biographies of celebrities that include Princess Diana, Maria Callas, Judy Garland, Katharine Hepburn, Vivien Leigh, Margaret Mitchell, Ronald Reagan, Barbra Streisand ...

. Before departing for France, he gave Mitchell an engagement ring.

On September 14, while she was enrolled at Smith College, Henry was mortally wounded in action in France and died on October 17.Mead, F.S., ''Harvard's Military Record in the World War'', p. 450. As Henry waited in the Verdun trenches, shortly before being wounded, he composed a poem on a leaf torn from his field notebook, found later among his effects. The last stanza of Lieutenant Clifford W. Henry's poem follows:

Henry repeatedly advanced in front of the platoon he commanded, drawing machine-gun fire so that the German nests could be located and wiped out by his men. Although wounded in the leg in this effort, his death was the result of shrapnel wounds from an air bomb dropped by a German plane. He was awarded the French ''If "out of luck" at duty's call In glorious action I should fall At God's behest, May those I hold most dear and best Know I have stood the acid test Should I "go West."

Croix de guerre

The ''Croix de Guerre'' (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awa ...

avec palme'' for his acts of heroism. From the President of the United States, the Commander in Chief of the United States Armed Forces

The United States Armed Forces are the military forces of the United States. The armed forces consists of six service branches: the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and Coast Guard. The president of the United States is the ...

, he was presented with the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

*Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

*Distinguished Service Cross (U ...

and an Oak Leaf Cluster

An oak leaf cluster is a ribbon device to denote preceding decorations and awards consisting of a miniature bronze or silver twig of four oak leaves with three acorns on the stem. It is authorized by the United States Armed Forces for a speci ...

in lieu of a second Distinguished Service Cross.

Clifford Henry was the great love of Margaret Mitchell's life, according to her brother. In a letter to a friend (A. Edee, March 26, 1920), Mitchell wrote of Clifford that she had a "memory of a love that had in it no trace of physical passion".

Mitchell had vague aspirations of a career in psychiatry,Pierpont, Claudia Roth. "A Critic at Large: A Study in Scarlett." ''The New Yorker'', August 31, 1992, p. 93-94. but her future was derailed by an event that killed over fifty million people worldwide, the 1918 flu pandemic

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

. On January 25, 1919, her mother, May Belle Mitchell, succumbed to pneumonia from the "Spanish flu". Mitchell arrived home from college a day after her mother had died. Knowing her death was imminent, May Belle Mitchell wrote her daughter a brief letter and advised her:

Give of yourself with both hands and overflowing heart, but give only the excess after you have lived your own life.An average student at Smith College, Mitchell did not excel in any area of academics. She held a low estimation of her writing abilities. Even though her English professor had praised her work, she felt the praise was undue. After finishing her freshman year at Smith, Mitchell returned to Atlanta to take over the household for her father and never returned to college. In October 1919, while regaining her strength after an

appendectomy

An appendectomy, also termed appendicectomy, is a Surgery, surgical operation in which the vermiform appendix (a portion of the intestine) is removed. Appendectomy is normally performed as an urgent or emergency procedure to treat complicated acu ...

, she confided to a friend that giving up college and her dreams of a "journalistic career" to keep house and take her mother's place in society meant "giving up all the worthwhile things that counted for—nothing!"

Marriage

Margaret began using the name "Peggy" at Washington Seminary, and the abbreviated form "Peg" at Smith College, when she found an icon for herself in the mythological winged horse, "Pegasus

Pegasus ( grc-gre, Πήγασος, Pḗgasos; la, Pegasus, Pegasos) is one of the best known creatures in Greek mythology. He is a winged divine stallion usually depicted as pure white in color. He was sired by Poseidon, in his role as hor ...

", that inspires poets. Peggy made her Atlanta society debut

Debut or début (the first public appearance of a person or thing) may refer to:

* Debut (society), the formal introduction of young upper-class women to society

* Debut novel, an author's first published novel

Film and television

* ''The Debu ...

in the 1920 winter season. In the "gin and jazz style" of the times, she did her "flapping

Flapping or tapping, also known as alveolar flapping, intervocalic flapping, or ''t''-voicing, is a phonological process found in many varieties of English, especially North American, Cardiff, Ulster, Australian and New Zealand English, whereby ...

" in the 1920s.Wolfe, Margaret Ripley. ''Daughters of Canaan: a saga of southern women''. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1995. p. 150. At a 1921 Atlanta debutante charity ball, she performed an Apache dance

Apache, or La Danse Apache, Bowery Waltz, Apache Turn, Apache Dance and Tough Dance is a highly dramatic dance associated in popular culture with Parisian street culture at the beginning of the 20th century. In fin de siècle Paris young members ...

. The dance included a kiss with her male partner that shocked Atlanta high society

High society, sometimes simply society, is the behavior and lifestyle of people with the highest levels of wealth and social status. It includes their related affiliations, social events and practices. Upscale social clubs were open to men based ...

and led to her being blacklisted from the Junior League

The Association of Junior Leagues International, Inc. (Junior League or JL) is a private, nonprofit educational women's volunteer organization aimed at improving communities and the social, cultural, and political fabric of civil society. With ...

. The Apache and the Tango

Tango is a partner dance and social dance that originated in the 1880s along the Río de la Plata, the natural border between Argentina and Uruguay. The tango was born in the impoverished port areas of these countries as the result of a combina ...

were scandalous dances for their elements of eroticism, the latter popularized in a 1921 silent film

A silent film is a film with no synchronized recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) or key lines of dialogue may, when ...

, ''The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse'', that made its lead actor, Rudolph Valentino

Rodolfo Pietro Filiberto Raffaello Guglielmi di Valentina d'Antonguolla (May 6, 1895 – August 23, 1926), known professionally as Rudolph Valentino and nicknamed The Latin Lover, was an Italian actor based in the United States who starred ...

, a sex symbol

A sex symbol or icon is a person or character widely considered sexually attractive.Pam Cook, "The trouble with sex: Diana Dors and the Blonde bombshell phenomenon", In: Bruce Babinigton (ed.), ''British Stars and Stardom: From Alma Taylor to ...

for his ability to Tango.

Mitchell was, in her own words, an "unscrupulous flirt". She found herself engaged to five men, but maintained that she neither lied to or misled any of them. A local gossip columnist, who wrote under the name Polly Peachtree, described Mitchell's love life in a 1922 column:

...she has in her brief life, perhaps, had more men really, truly 'dead in love' with her, more honest-to-goodness suitors than almost any other girl in Atlanta.In April 1922, Mitchell was seeing two men almost daily: one was Berrien ("Red") Kinnard Upshaw (March 10, 1901 – January 13, 1949), whom she is thought to have met in 1917 at a dance hosted by the parents of one of her friends, and the other, Upshaw's roommate and friend, John Robert Marsh (October 6, 1895 – March 5, 1952), a copy editor from

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

who worked for the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

.Bartley, N.V., ''The Evolution of Southern Culture'', p. 95-96. Upshaw was an Atlanta boy, a few months younger than Mitchell, whose family moved to Raleigh, North Carolina

Raleigh (; ) is the capital city of the state of North Carolina and the List of North Carolina county seats, seat of Wake County, North Carolina, Wake County in the United States. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, second-most ...

in 1916. In 1919 he was appointed to the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

, but resigned for academic deficiencies on January 5, 1920. He was readmitted in May, then 19 years old, and spent two months at sea before resigning a second time on September 1, 1920. Unsuccessful in his educational pursuits and with no job, in 1922 Upshaw earned money bootlegging alcohol out of the Georgia mountains.

Although her family disapproved, Peggy and Red married on September 2, 1922; the best man at their wedding was John Marsh, who would become her second husband. The couple resided at the Mitchell home with her father. By December the marriage to Upshaw had dissolved and he left. Mitchell suffered physical and emotional abuse, the result of Upshaw's alcoholism and violent temper. Upshaw agreed to an uncontested divorce after John Marsh gave him a loan and Mitchell agreed not to press assault charges against him. Upshaw and Mitchell were divorced on October 16, 1924.

During this time, Mitchell left the Catholic Church and became an Episcopalian

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of the l ...

.

On July 4, 1925, 24-year-old Margaret Mitchell and 29-year-old John Marsh were married in the Unitarian-Universalist Church. The Marshes made their home at the Crescent Apartments in Atlanta, taking occupancy of Apt. 1, which they affectionately named "The Dump" (now the Margaret Mitchell House and Museum

The Margaret Mitchell House is a historic house museum located in Atlanta, Georgia. The structure was the home of author Margaret Mitchell in the early 20th century. It is located in Midtown, at 979 Crescent Avenue. Constructed by Cornelius J ...

).Brown, E.F., et al., ''Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind: a bestseller's odyssey from Atlanta to Hollywood'', p. 8.

Reporter for ''The Atlanta Journal''

While still legally married to Upshaw and needing income for herself, Mitchell got a job writing feature articles for ''The Atlanta Journal

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the only major daily newspaper in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger between ...

Sunday Magazine''. She received almost no encouragement from her family or "society" to pursue a career in journalism, and had no prior newspaper experience.Wolfe, M.R., ''Daughters of Canaan: a saga of southern women'', p. 149. Medora Field Perkerson, who hired Mitchell said:

There had been some skepticism on the Atlanta Journal Magazine staff when Peggy came to work as a reporter. Debutantes slept late in those days and didn't go in for jobs.Her first story, ''Atlanta Girl Sees Italian Revolution'', by Margaret Mitchell Upshaw, appeared on December 31, 1922. She wrote on a wide range of topics, from fashions to

Confederate generals

The general officers of the Confederate States Army (CSA) were the senior military leaders of the Confederacy during the American Civil War of 1861–1865. They were often former officers from the United States Army (the regular army) prior to t ...

and King Tut

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

. In an article that appeared on July 1, 1923, ''Valentino Declares He Isn't a Sheik'', she interviewed celebrity actor Rudolph Valentino

Rodolfo Pietro Filiberto Raffaello Guglielmi di Valentina d'Antonguolla (May 6, 1895 – August 23, 1926), known professionally as Rudolph Valentino and nicknamed The Latin Lover, was an Italian actor based in the United States who starred ...

, referring to him as "Sheik" from his film role. Less thrilled by his looks than his "chief charm", his "low, husky voice with a soft, sibilant accent", she described his face as "swarthy":

His face was swarthy, so brown that his white teeth flashed in startling contrast to his skin; his eyes—tired, bored, but courteous.Mitchell was quite thrilled when Valentino took her in his arms and carried her inside from the rooftop of the

Georgian Terrace Hotel

The Georgian Terrace Hotel in Midtown Atlanta, part of the Fox Theatre Historic District, was designed by architect William Lee Stoddart in a Beaux-Arts style that was intended to evoke the architecture of Paris. Construction commenced on July 2 ...

.

Many of her stories were vividly descriptive. In an article titled, ''Bridesmaid of Eighty-Seven Recalls Mittie Roosevelt's Wedding'', she wrote of a white-columned mansion in which lived the last surviving bridesmaid at Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

's mother's wedding:

The tall white columns glimpsed through the dark green of cedar foliage, the wide veranda encircling the house, the stately silence engendered by the century-old oaks evoke memories ofIn another article, ''Georgia's Empress and Women Soldiers'', she wrote short sketches of four notable Georgia women. One was the first woman to serve in theThomas Nelson Page Thomas Nelson Page (April 23, 1853 – November 1, 1922) was an American lawyer, politician, and writer. He served as the U.S. ambassador to Italy from 1913 to 1919 under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson during World War I. In his ...'s ''On Virginia''. The atmosphere of dignity, ease, and courtesy that was the soul of the Old South breathes from this old mansion...

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

, Rebecca Latimer Felton

Rebecca Ann Felton (née Latimer; June 10, 1835 – January 24, 1930) was an American writer, lecturer, feminist, suffragist, reformer, slave owner, and politician who was the first woman to serve in the United States Senate, although she serve ...

, a suffragist who held white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other Race (human classification), races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any Power (social and polit ...

views. The other women were: Nancy Hart

Nancy Morgan Hart (c. 1735–1830) was a rebel heroine of the American Revolutionary War, noted for her exploits against Loyalists in the northeast Georgia backcountry. She is characterized as a tough, resourceful frontier woman who repeatedly ...

, Lucy Mathilda Kenny (also known as Private Bill Thompson of the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

) and Mary Musgrove

Mary Musgrove (Muscogee name, Coosaponakeesa, c. 1700–1765) was a leading figure in early Georgia history. Mary was the daughter of Edward Griffin, a trader from Charles Town in the Province of Carolina, of English heritage, and a Muscogee Cree ...

. The article generated mail and controversy from her readers. Mitchell received criticism for depicting "strong women who did not fit the accepted standards of femininity."

Mitchell's journalism career, which began in 1922, came to an end less than four years later; her last article appeared on May 9, 1926. Several months after marrying John Marsh, Mitchell quit due to an ankle injury that would not heal properly and chose to become a full-time wife.Jones, A. G., ''Tomorrow is Another Day: the woman writer in the South, 1859–1936'', p. 314. During the time Mitchell worked for the ''Atlanta Journal'', she wrote 129 feature articles, 85 news stories, and several book reviews.

Interest in erotica

Mitchell began collecting erotica from book shops in New York City while in her twenties. The newlywed Marshes and their social group were interested in "all forms of sexual expression". Mitchell discussed her interest in dirty book shops and sexually explicit prose in letters to a friend, Harvey Smith. Smith noted her favorite reads were ''Fanny Hill

''Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure''—popularly known as ''Fanny Hill''—is an erotic novel by English novelist John Cleland first published in London in 1748. Written while the author was in debtors' prison in London,Wagner, "Introduction", ...

'', ''The Perfumed Garden

''The Perfumed Garden of Sensual Delight'' ( ar, الروض العاطر في نزهة الخاطر ''Al-rawḍ al-ʿāṭir fī nuzhaẗ al-ḫāṭir'') is a fifteenth-century Arabic sex manual and work of erotic literature by Muhammad ibn ...

'', and ''Aphrodite

Aphrodite ( ; grc-gre, Ἀφροδίτη, Aphrodítē; , , ) is an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess . Aphrodite's major symbols include ...

''.Young, E., ''Disarming the Nation: women's writing and the American Civil War'', p. 245.

Mitchell developed an appreciation for the works of Southern writer James Branch Cabell

James Branch Cabell (; April 14, 1879 – May 5, 1958) was an American author of fantasy fiction and ''belles-lettres''. Cabell was well-regarded by his contemporaries, including H. L. Mencken, Edmund Wilson, and Sinclair Lewis. His works ...

, and his 1919 classic, ''Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice

''Jurgen, A Comedy of Justice'' is a fantasy novel by American writer James Branch Cabell, which gained fame (or notoriety) shortly after its publication in 1919. It is a humorous romp through a medieval cosmos, including a send-up of Arthurian l ...

''. She read books about sexology

Sexology is the scientific study of human sexuality, including human sexual interests, behaviors, and functions. The term ''sexology'' does not generally refer to the non-scientific study of sexuality, such as social criticism.

Sexologists app ...

and took particular interest in the case studies of Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality in ...

, a British physician who studied human sexuality. During this period in which Mitchell was reading pornography and sexology, she was also writing ''Gone with the Wind''.

Novelist

Early works

''Lost Laysen''

Mitchell wrote a romance novella, ''Lost Laysen

''Lost Laysen'' is a novella by Margaret Mitchell. Although it was written in 1916, it was not published until 1996.

Mitchell, who is best known as the author of ''Gone with the Wind'', was believed to have only written one full book during her l ...

'', when she was fifteen years old (1916). She gave ''Lost Laysen'', which she had written in two notebooks, to a boyfriend, Henry Love Angel. He died in 1945 and the novella remained undiscovered among some letters she had written to him until 1994. The novella was published in 1996, eighty years after it was written, and became a ''New York Times'' Best Seller.

In ''Lost Laysen'', Mitchell explores the dynamics of three male characters and their relationship to the only female character, Courtenay Ross, a strong-willed American missionary to the South Pacific island of Laysen. The narrator of the tale is Billy Duncan, "a rough, hardened soldier of fortune", who is frequently involved in fights that leave him near death. Courtenay quickly observes Duncan's hard-muscled body as he works shirtless aboard a ship called ''Caliban''. Courtenay's suitor is Douglas Steele, an athletic man who apparently believes Courtenay is helpless without him. He follows Courtenay to Laysen to protect her from perceived foreign savages. The third male character is the rich, powerful yet villainous Juan Mardo. He leers at Courtenay and makes rude comments of a sexual nature, in Japanese nonetheless. Mardo provokes Duncan and Steele, and each feels he must defend Courtenay's honor. Ultimately Courtenay defends her own honor rather than submit to shame.

Mitchell's half-breed

antagonist, Juan Mardo, lurks in the shadows of the story and has no dialogue. The reader learns of Mardo's evil intentions through Duncan:

They were saying that Juan Mardo had his eye on you—and intended to have you—any way he could get you!Mardo's desires are similar to those of Rhett Butler in his ardent pursuit of Scarlett O'Hara in Mitchell's epic novel, ''Gone with the Wind''. Rhett tells Scarlett:

I always intended having you, one way or another.The "other way" is rape. In ''Lost Laysen'' the male seducer is replaced with the male rapist.Young, E., ''Disarming the Nation: women's writing and the American Civil War'', p. 241.

''The Big Four''

In Mitchell's teenage years, she is known to have written a 400-page novel about girls in a boarding school, ''The Big Four''. The novel is thought to be lost; Mitchell destroyed some of her manuscripts herself and others were destroyed after her death.''Ropa Carmagin''

In the 1920s Mitchell completed a novelette, ''Ropa Carmagin'', about a Southern white girl who loves a biracial man. Mitchell submitted the manuscript toMacmillan Publishers

Macmillan Publishers (occasionally known as the Macmillan Group; formally Macmillan Publishers Ltd and Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC) is a British publishing company traditionally considered to be one of the 'Big Five' English language publi ...

in 1935 along with her manuscript for ''Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* Gone with the Wind (novel), ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* Gone with the Wind (film), ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Win ...

''. The novelette was rejected; Macmillan thought the story was too short for book form.

Writing ''Gone with the Wind''

In May 1926, after Mitchell had left her job at the ''Atlanta Journal'' and was recovering at home from her ankle injury, she wrote a society column for the ''Sunday Magazine'', "Elizabeth Bennet's Gossip", which she continued to write until August. Meanwhile, her husband was growing weary of lugging armloads of books home from the library to keep his wife's mind occupied while she hobbled around the house; he emphatically suggested that she write her own book instead:For God's sake, Peggy, can't you write a book instead of reading thousands of them?Oliphant, Sgt. H. N. "People on the Home Front: Margaret Mitchell". October 19, 1945. ''Yank'', p. 9.To aid her in her literary endeavors, John Marsh brought home a Remington Portable No. 3

typewriter

A typewriter is a mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an inked ribbon selectivel ...

(c. 1928). For the next three years Mitchell worked exclusively on writing a Civil War-era novel whose heroine was named Pansy O'Hara (prior to ''Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* Gone with the Wind (novel), ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* Gone with the Wind (film), ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Win ...

''s publication Pansy was changed to Scarlett). She used parts of the manuscript to prop up a wobbly couch.

In April 1935, Harold Latham

Harold Strong Latham (February 14, 1887 – March 6, 1969) was an American editor and publishing executive. He was editor-in-chief of Macmillan Inc., where he discovered and edited the works of notable writers including Margaret Mitchell and Jame ...

of Macmillan, an editor looking for new fiction, read her manuscript and saw that it could be a best-seller. After Latham agreed to publish the book, Mitchell worked for another six months checking the historical references and rewriting the opening chapter several times. Mitchell and John Marsh edited the final version of the novel. ''Gone with the Wind'' was published in June 1936.

World War II

During

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Margaret Mitchell was a volunteer for the American Red Cross

The American Red Cross (ARC), also known as the American National Red Cross, is a non-profit humanitarian organization that provides emergency assistance, disaster relief, and disaster preparedness education in the United States. It is the desi ...

and she raised money for the war effort by selling war bonds. She was active in Home Defense, sewed hospital gowns and put patches on trousers. Her personal attention, however, was devoted to writing letters to men in uniform—soldiers, sailors, and marines, sending them humor, encouragement, and her sympathy.

The USS ''Atlanta'' (CL-51) was a light cruiser used as an anti-aircraft ship of the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

sponsored by Margaret Mitchell and used in the naval Battle of Midway

The Battle of Midway was a major naval battle in the Pacific Theater of World War II that took place on 4–7 June 1942, six months after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and one month after the Battle of the Coral Sea. The U.S. Navy under Adm ...

and the Eastern Solomons. The ship was heavily damaged during night surface action on November 13, 1942, during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, sometimes referred to as the Third and Fourth Battles of Savo Island, the Battle of the Solomons, the Battle of Friday the 13th, or, in Japanese sources, the , took place from 12 to 15 November 1942, and was t ...

and subsequently scuttled on orders of her captain having earned five battle stars

A service star is a miniature bronze or silver five-pointed star inch (4.8 mm) in diameter that is authorized to be worn by members of the eight uniformed services of the United States on medals and ribbons to denote an additional award or ser ...

and a Presidential Unit Citation as a "heroic example of invincible fighting spirit".

Mitchell sponsored a second light cruiser named after the city of Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

, the USS ''Atlanta'' (CL-104). On February 6, 1944, she christened ''Atlanta'' in Camden, New Jersey, and the cruiser began fighting operations in May 1945. ''Atlanta'' was a member of task forces protecting fast carriers, was operating off the coast of Honshū

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island separa ...

when the Japanese surrendered on August 15, 1945, and earned two battle stars. She was finally sunk during explosive testing off San Clemente Island

San Clemente Island (Tongva: ''Kinkipar''; Spanish: ''Isla de San Clemente'') is the southernmost of the Channel Islands of California. It is owned and operated by the United States Navy, and is a part of Los Angeles County. It is administered b ...

on October 1, 1970.

Death and legacy

Margaret Mitchell was struck by a speeding motorist as she crossed

Margaret Mitchell was struck by a speeding motorist as she crossed Peachtree Street

Peachtree Street is one of several major streets running through the city of Atlanta. Beginning at Five Points (Atlanta), Five Points in downtown Atlanta, it runs North through Midtown Atlanta, Midtown; a few blocks after entering into Buckhead ...

at 13th Street in Atlanta with her husband, John Marsh, while on her way to see the movie ''A Canterbury Tale

''A Canterbury Tale'' is a 1944 British film by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger starring Eric Portman, Sheila Sim, Dennis Price and Sgt. John Sweet; Esmond Knight provided narration and played two small roles. For the post-war American ...

'' on the evening of August 11, 1949. She died at age 48 at Grady Hospital

Grady Memorial Hospital, frequently referred to as Grady Hospital or simply Grady, is the public hospital for the city of Atlanta. It is the tenth-largest public hospital in the United States, and one of the busiest Level I trauma centers in th ...

five days later on August 16 without fully regaining consciousness.

Mitchell was struck by Hugh Gravitt, an off-duty taxi driver who was driving his personal vehicle. After the collision, Gravitt was arrested for drunken driving and released on a $5,450 bond until Mitchell's death.Obituary: Miss Mitchell, 49, Dead of Injuries(August 17, 1949) ''New York Times''. Retrieved May 14, 2011. Gravitt was originally charged with drunken driving, speeding, and driving on the wrong side of the road. He was convicted of involuntary manslaughter in November 1949 and sentenced to 18 months in jail. He served almost 11 months. Gravitt died in 1994 at the age of 74. Margaret Mitchell was buried at Oakland Cemetery,

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. When her husband John died in 1952, he was buried next to his wife.

In 1978, Mitchell was inducted into the Georgia Newspaper Hall of Fame The Georgia Newspaper Hall of Fame recognizes newspaper editors and publishers of the U.S. state of Georgia for their significant achievements or contributions. A permanent exhibit of the honorees is maintained at the Henry W. Grady College of Journ ...

, followed by the Georgia Women of Achievement

The Georgia Women of Achievement (GWA) recognizes women natives or residents of the U.S. state of Georgia for their significant achievements or statewide contributions. The concept was first proposed by Rosalynn Carter in 1988. The first induction ...

in 1994, and the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame

The Georgia Writers Hall of Fame honors writers who have made significant contributions to the literary legacy of the state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. Established in 2000 by the University of Georgia Libraries’ Hargrett Rare Book and Manu ...

in 2000.

In 1994, Shannen Doherty

Shannen Doherty (, born April 12, 1971) is an American actress. She is known for her roles as Jenny Wilder in ''Little House on the Prairie'' (1982–1983); Maggie Malene in ''Girls Just Want to Have Fun'' (1985); Kris Witherspoon in '' Our Hous ...

starred in the television film '' A Burning Passion: The Margaret Mitchell Story'', a fictionalized account of Mitchell's life directed by Larry Peerce

Lawrence "Larry" Peerce (born April 19, 1930) is an American film and TV director whose work includes the theatrical feature ''Goodbye, Columbus'' (1969), the early rock and roll concert film '' The Big T.N.T. Show'' (1966), ''One Potato, Two Pot ...

.

When Mitchell's nephew, Joseph Mitchell

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, died in 2011, he left fifty percent of trademark and literary rights of the Margaret Mitchell Estate, as well as some personal belongings of Mitchell's, to the Archdiocese of Atlanta

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

.

References

Further reading

* Bonner, Peter.Lost In Yesterday: Commemorating The 70th Anniversary of Margaret Mitchell's 'Gone With The Wind'