Mandatory Palestine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the

Following the arrival of the British, Arab inhabitants established Muslim-Christian Associations in all of the major towns.Ira M. Lapidus, ''A History of Islamic Societies'', 2002: "The first were the nationalists, who in 1918 formed the first Muslim-Christian associations to protest against the Jewish national home" p.558 In 1919 they joined to hold the first Palestine Arab Congress in Jerusalem. It was aimed primarily at representative government and opposition to the

Following the arrival of the British, Arab inhabitants established Muslim-Christian Associations in all of the major towns.Ira M. Lapidus, ''A History of Islamic Societies'', 2002: "The first were the nationalists, who in 1918 formed the first Muslim-Christian associations to protest against the Jewish national home" p.558 In 1919 they joined to hold the first Palestine Arab Congress in Jerusalem. It was aimed primarily at representative government and opposition to the

One of the first actions of the newly installed civil administration was to begin granting concessions from the Mandatory government over key economic assets. In 1921 the government granted Pinhas Rutenberg – a Jewish entrepreneur – concessions for the production and distribution of electrical power. Rutenberg soon established an electric company whose shareholders were Zionist organisations, investors, and philanthropists. Palestinian-Arabs saw it as proof that the British intended to favour Zionism. The British administration claimed that electrification would enhance the economic development of the country as a whole, while at the same time securing their commitment to facilitate a Jewish National Home through economicrather than politicalmeans.

In May 1921, almost 100 died in rioting in Jaffa after a disturbance between rival Jewish left-wing protestors was followed by attacks by Arabs on Jews.

Samuel tried to establish self-governing institutions in Palestine, as required by the mandate, but the Arab leadership refused to co-operate with any institution which included Jewish participation. When Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

One of the first actions of the newly installed civil administration was to begin granting concessions from the Mandatory government over key economic assets. In 1921 the government granted Pinhas Rutenberg – a Jewish entrepreneur – concessions for the production and distribution of electrical power. Rutenberg soon established an electric company whose shareholders were Zionist organisations, investors, and philanthropists. Palestinian-Arabs saw it as proof that the British intended to favour Zionism. The British administration claimed that electrification would enhance the economic development of the country as a whole, while at the same time securing their commitment to facilitate a Jewish National Home through economicrather than politicalmeans.

In May 1921, almost 100 died in rioting in Jaffa after a disturbance between rival Jewish left-wing protestors was followed by attacks by Arabs on Jews.

Samuel tried to establish self-governing institutions in Palestine, as required by the mandate, but the Arab leadership refused to co-operate with any institution which included Jewish participation. When Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

Answers.com Arabs protested against the distribution of the seats, arguing that as they constituted 88% of the population, having only 43% of the seats was unfair. Elections took place in February and March 1923, but due to an Arab

The death of al-Qassam on 20 November 1935 generated widespread outrage in the Arab community. Huge crowds accompanied Qassam's body to his grave in Haifa. A few months later, in April 1936, the Arab national

The death of al-Qassam on 20 November 1935 generated widespread outrage in the Arab community. Huge crowds accompanied Qassam's body to his grave in Haifa. A few months later, in April 1936, the Arab national

''Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization''

, p. 391.Morris, Benny (2009). ''One State, Two States: Resolving the Israel/Palestine Conflict'', p. 66 p. 11 "while the Zionist movement, after much agonising, accepted the principle of partition and the proposals as a basis for negotiation"; p. 49 "In the end, after bitter debate, the Congress equivocally approved—by a vote of 299 to 160—the Peel recommendations as a basis for further negotiation." In a letter to his son in October 1937, Ben-Gurion explained that partition would be a first step to "possession of the land as a whole". The same sentiment was recorded by Ben-Gurion on other occasions, such as at a meeting of the Jewish Agency executive in June 1938, as well as by Chaim Weizmann. Following the London Conference (1939) the British Government published a White Paper which proposed a limit to Jewish immigration from Europe, restrictions on Jewish land purchases, and a program for creating an independent state to replace the Mandate within ten years. This was seen by the Yishuv as betrayal of the mandatory terms, especially in light of the increasing persecution of Jews in Europe. In response, Zionists organised '' Aliyah Bet'', a program of illegal immigration into Palestine.

Link

.

The Jewish Lehi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel) and Irgun (National Military Organisation) movements initiated violent uprisings against the British Mandate in the 1940s. On 6 November 1944, Eliyahu Hakim and Eliyahu Bet Zuri (members of Lehi) assassinated Lord Moyne in Cairo. Moyne was the British Minister of State for the Middle East and the assassination is said by some to have turned British Prime Minister

The Jewish Lehi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel) and Irgun (National Military Organisation) movements initiated violent uprisings against the British Mandate in the 1940s. On 6 November 1944, Eliyahu Hakim and Eliyahu Bet Zuri (members of Lehi) assassinated Lord Moyne in Cairo. Moyne was the British Minister of State for the Middle East and the assassination is said by some to have turned British Prime Minister

The negative publicity resulting from the situation in Palestine caused the Mandate to become widely unpopular in Britain, and caused the United States Congress to delay granting the British vital loans for reconstruction. The British Labour party had promised before its election in 1945 to allow mass Jewish migration into Palestine but reneged on this promise once in office. Anti-British Jewish militancy increased and the situation required the presence of over 100,000 British troops in the country. Following the Acre Prison Break and the retaliatory hanging of British Sergeants by the Irgun, the British announced their desire to terminate the mandate and to withdraw by no later than the beginning of August 1948.

The

The negative publicity resulting from the situation in Palestine caused the Mandate to become widely unpopular in Britain, and caused the United States Congress to delay granting the British vital loans for reconstruction. The British Labour party had promised before its election in 1945 to allow mass Jewish migration into Palestine but reneged on this promise once in office. Anti-British Jewish militancy increased and the situation required the presence of over 100,000 British troops in the country. Following the Acre Prison Break and the retaliatory hanging of British Sergeants by the Irgun, the British announced their desire to terminate the mandate and to withdraw by no later than the beginning of August 1948.

The

Encyclopædia Britannica Online School Edition, 2006. 15 May 2006. Some Jewish organisations also opposed the proposal. Irgun leader

When the UK announced the independence of Transjordan in 1946, the final Assembly of the League of Nations and the General Assembly both adopted resolutions welcoming the news. The Jewish Agency objected, claiming that Transjordan was an integral part of Palestine, and that according to Article 80 of the UN Charter, the Jewish people had a secured interest in its territory.

During the General Assembly deliberations on Palestine, there were suggestions that it would be desirable to incorporate part of Transjordan's territory into the proposed Jewish state. A few days before the adoption of Resolution 181 (II) on 29 November 1947, US Secretary of State Marshall noted frequent references had been made by the Ad Hoc Committee regarding the desirability of the Jewish State having both the Negev and an "outlet to the Red Sea and the Port of Aqaba". According to John Snetsinger, Chaim Weizmann visited President Truman on 19 November 1947 and said it was imperative that the Negev and Port of Aqaba be within the Jewish state. Truman telephoned the US delegation to the UN and told them he supported Weizmann's position. However, the Trans-Jordan memorandum excluded territories of the Emirate of Transjordan from any Jewish settlement.

Immediately after the UN resolution, the 1947-1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine broke out between the Arab and Jewish communities, and British authority began to break down. On 16 December 1947, the Palestine Police Force withdrew from the Tel Aviv area, home to more than half the Jewish population, and turned over responsibility for the maintenance of law and order to Jewish police. As the civil war raged on, British military forces gradually withdrew from Palestine, although they occasionally intervened in favour of either side. Many of these areas became war zones. The British maintained strong presences in Jerusalem and Haifa, even as Jerusalem came under siege by Arab forces and became the scene of fierce fighting, though the British occasionally intervened in the fighting, largely to secure their evacuation routes, including by proclaiming martial law and enforcing truces. The Palestine Police Force was largely inoperative, and government services such as social welfare, water supplies, and postal services were withdrawn. In March 1948, all British judges in Palestine were sent back to Britain. In April 1948, the British withdrew from most of Haifa but retained an enclave in the port area to be used in the evacuation of British forces, and retained

When the UK announced the independence of Transjordan in 1946, the final Assembly of the League of Nations and the General Assembly both adopted resolutions welcoming the news. The Jewish Agency objected, claiming that Transjordan was an integral part of Palestine, and that according to Article 80 of the UN Charter, the Jewish people had a secured interest in its territory.

During the General Assembly deliberations on Palestine, there were suggestions that it would be desirable to incorporate part of Transjordan's territory into the proposed Jewish state. A few days before the adoption of Resolution 181 (II) on 29 November 1947, US Secretary of State Marshall noted frequent references had been made by the Ad Hoc Committee regarding the desirability of the Jewish State having both the Negev and an "outlet to the Red Sea and the Port of Aqaba". According to John Snetsinger, Chaim Weizmann visited President Truman on 19 November 1947 and said it was imperative that the Negev and Port of Aqaba be within the Jewish state. Truman telephoned the US delegation to the UN and told them he supported Weizmann's position. However, the Trans-Jordan memorandum excluded territories of the Emirate of Transjordan from any Jewish settlement.

Immediately after the UN resolution, the 1947-1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine broke out between the Arab and Jewish communities, and British authority began to break down. On 16 December 1947, the Palestine Police Force withdrew from the Tel Aviv area, home to more than half the Jewish population, and turned over responsibility for the maintenance of law and order to Jewish police. As the civil war raged on, British military forces gradually withdrew from Palestine, although they occasionally intervened in favour of either side. Many of these areas became war zones. The British maintained strong presences in Jerusalem and Haifa, even as Jerusalem came under siege by Arab forces and became the scene of fierce fighting, though the British occasionally intervened in the fighting, largely to secure their evacuation routes, including by proclaiming martial law and enforcing truces. The Palestine Police Force was largely inoperative, and government services such as social welfare, water supplies, and postal services were withdrawn. In March 1948, all British judges in Palestine were sent back to Britain. In April 1948, the British withdrew from most of Haifa but retained an enclave in the port area to be used in the evacuation of British forces, and retained

21

"In 1948 half of Palestine's 1.4 million Arabs were uprooted from their homes and became refugees". Over the next few days, approximately 700 Lebanese, 1,876 Syrian, 4,000 Iraqi, and 2,800 Egyptian troops crossed over the borders into Palestine, starting the

– Minutes of the Permanent Mandates Commission/League of Nations 32nd session, 18 August 1937

Judge Higgins explained that the Palestinian people are entitled to their territory, to exercise self-determination, and to have their own State." The Court said that specific guarantees regarding freedom of movement and access to the Holy Sites contained in the Treaty of Berlin (1878) had been preserved under the terms of the Palestine Mandate and a chapter of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. According to historian Rashid Khalidi, the mandate ignored the political rights of the Arabs. The Arab leadership repeatedly pressed the British to grant them national and political rights, such as representative government, over Jewish national and political rights in the remaining 23% of the Mandate of Palestine which the British had set aside for a Jewish homeland. The Arabs reminded the British of President Wilson's Fourteen Points and British promises during the First World War. The British however made acceptance of the terms of the mandate a precondition for any change in the constitutional position of the Arabs. A legislative council was proposed in The Palestine Order in Council, of 1922 which implemented the terms of the mandate. It stated that: "No Ordinance shall be passed which shall be in any way repugnant to or inconsistent with the provisions of the Mandate." For the Arabs, this decree was unacceptable, akin to "self murder". As a result, the Arabs boycotted the elections to the Council held in 1923, which were subsequently annulled. During the interwar period, the British rejected the principle of majority rule or any other measure that would give Arabs control of the government. The terms of the mandate required the establishment of self-governing institutions in both Palestine and Transjordan. In 1947, Foreign Secretary Bevin admitted that during the previous twenty-five years the British had done their best to further the legitimate aspirations of the Jewish communities without prejudicing the interests of the Arabs, but had failed to "secure the development of self-governing institutions" in accordance with the terms of the Mandate.

Under the British Mandate, the office of "Mufti of Jerusalem", traditionally limited in authority and geographical scope, was refashioned into that of "Grand Mufti of Palestine". Furthermore, a Supreme Muslim Council (SMC) was established and given various duties, such as the administration of religious endowments and the appointment of religious judges and local muftis. In Ottoman times, these duties had been fulfilled by the bureaucracy in Istanbul. In dealings with the Palestinian Arabs, the British negotiated with the elite rather than the middle or lower classes. They chose Hajj Amin al-Husseini to become Grand Mufti, although he was young and had received the fewest votes from Jerusalem's Islamic leaders. One of the mufti's rivals, Raghib Bey al-Nashashibi, had already been appointed mayor of Jerusalem in 1920, replacing

Under the British Mandate, the office of "Mufti of Jerusalem", traditionally limited in authority and geographical scope, was refashioned into that of "Grand Mufti of Palestine". Furthermore, a Supreme Muslim Council (SMC) was established and given various duties, such as the administration of religious endowments and the appointment of religious judges and local muftis. In Ottoman times, these duties had been fulfilled by the bureaucracy in Istanbul. In dealings with the Palestinian Arabs, the British negotiated with the elite rather than the middle or lower classes. They chose Hajj Amin al-Husseini to become Grand Mufti, although he was young and had received the fewest votes from Jerusalem's Islamic leaders. One of the mufti's rivals, Raghib Bey al-Nashashibi, had already been appointed mayor of Jerusalem in 1920, replacing

During the Mandate, the Yishuv or Jewish community in Palestine, grew from one-sixth to almost one-third of the population. According to official records, 367,845 Jews and 33,304 non-Jews immigrated legally between 1920 and 1945. It was estimated that another 50–60,000 Jews and a marginal number of Arabs, the latter mostly on a seasonal basis, immigrated illegally during this period. Immigration accounted for most of the increase of Jewish population, while the non-Jewish population increase was largely natural. Of the Jewish immigrants, in 1939 most had come from Germany and Czechoslovakia, but in 1940–1944 most came from Romania and Poland, with an additional 3,530 immigrants arriving from Yemen during the same period.

Initially, Jewish immigration to Palestine met little opposition from the Palestinian Arabs. However, as

During the Mandate, the Yishuv or Jewish community in Palestine, grew from one-sixth to almost one-third of the population. According to official records, 367,845 Jews and 33,304 non-Jews immigrated legally between 1920 and 1945. It was estimated that another 50–60,000 Jews and a marginal number of Arabs, the latter mostly on a seasonal basis, immigrated illegally during this period. Immigration accounted for most of the increase of Jewish population, while the non-Jewish population increase was largely natural. Of the Jewish immigrants, in 1939 most had come from Germany and Czechoslovakia, but in 1940–1944 most came from Romania and Poland, with an additional 3,530 immigrants arriving from Yemen during the same period.

Initially, Jewish immigration to Palestine met little opposition from the Palestinian Arabs. However, as

After transition to the British rule, much of the agricultural land in Palestine (about one third of the whole territory) was still owned by the same landowners as under Ottoman rule, mostly powerful Arab clans and local Muslim sheikhs. Other lands had been held by foreign Christian organisations (most notably the Greek Orthodox Church), as well as Jewish private and Zionist organisations, and to lesser degree by small minorities of Baháʼís, Samaritans and Circassians.

As of 1931, the territory of the British Mandate of Palestine was , of which or 33% were arable. Official statistics show that Jews privately and collectively owned , or 5.23% of Palestine's total in 1945. The Jewish owned agricultural land was largely located in the Galilee and along the coastal plain. Estimates of the total volume of land that Jews had purchased by 15 May 1948 are complicated by illegal and unregistered land transfers, as well as by the lack of data on land concessions from the Palestine administration after 31 March 1936. According to Avneri, Jews held of land in 1947, or 6.94% of the total. Stein gives the estimate of as of May 1948, or 7.51% of the total. According to Fischbach, by 1948, Jews and Jewish companies owned 20% percent of all cultivable land in the country.

According to Clifford A. Wright, by the end of the British Mandate period in 1948, Jewish farmers cultivated 425,450 dunams of land, while Palestinian farmers had 5,484,700 dunams of land under cultivation. The 1945 UN estimate shows that Arab ownership of arable land was on average 68% of a district, ranging from 15% ownership in the Beer-Sheba district to 99% ownership in the Ramallah district. These data cannot be fully understood without comparing them to those of neighbouring countries: in Iraq, for instance, still in 1951 only 0.3 per cent of registered land (or 50 per cent of the total amount) was categorised as 'private property'.

After transition to the British rule, much of the agricultural land in Palestine (about one third of the whole territory) was still owned by the same landowners as under Ottoman rule, mostly powerful Arab clans and local Muslim sheikhs. Other lands had been held by foreign Christian organisations (most notably the Greek Orthodox Church), as well as Jewish private and Zionist organisations, and to lesser degree by small minorities of Baháʼís, Samaritans and Circassians.

As of 1931, the territory of the British Mandate of Palestine was , of which or 33% were arable. Official statistics show that Jews privately and collectively owned , or 5.23% of Palestine's total in 1945. The Jewish owned agricultural land was largely located in the Galilee and along the coastal plain. Estimates of the total volume of land that Jews had purchased by 15 May 1948 are complicated by illegal and unregistered land transfers, as well as by the lack of data on land concessions from the Palestine administration after 31 March 1936. According to Avneri, Jews held of land in 1947, or 6.94% of the total. Stein gives the estimate of as of May 1948, or 7.51% of the total. According to Fischbach, by 1948, Jews and Jewish companies owned 20% percent of all cultivable land in the country.

According to Clifford A. Wright, by the end of the British Mandate period in 1948, Jewish farmers cultivated 425,450 dunams of land, while Palestinian farmers had 5,484,700 dunams of land under cultivation. The 1945 UN estimate shows that Arab ownership of arable land was on average 68% of a district, ranging from 15% ownership in the Beer-Sheba district to 99% ownership in the Ramallah district. These data cannot be fully understood without comparing them to those of neighbouring countries: in Iraq, for instance, still in 1951 only 0.3 per cent of registered land (or 50 per cent of the total amount) was categorised as 'private property'.

* Land Transfer Ordinance of 1920

* 1926 Correction of Land Registers Ordinance

* Land Settlement Ordinance of 1928

* Land Transfer Regulations of 1940

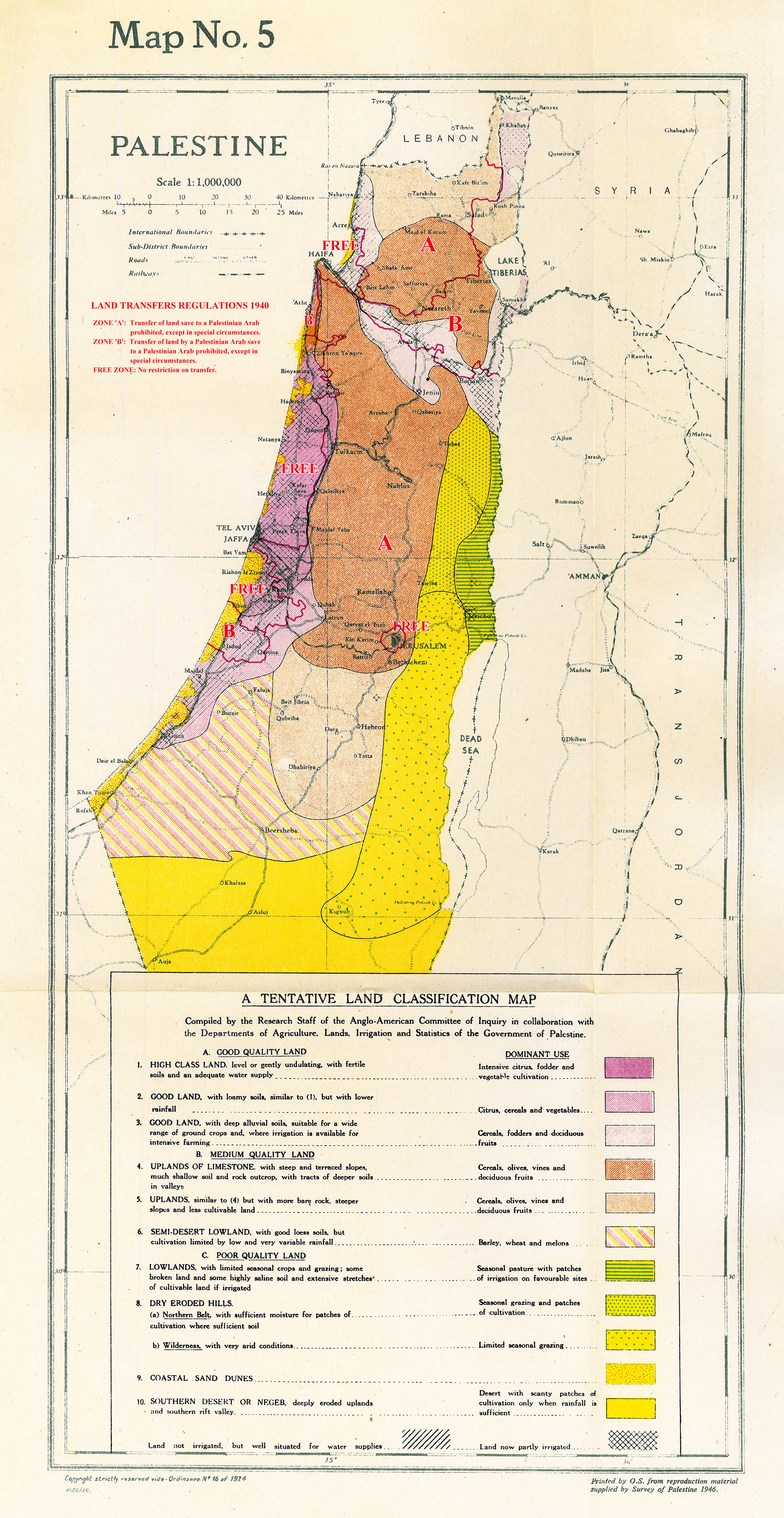

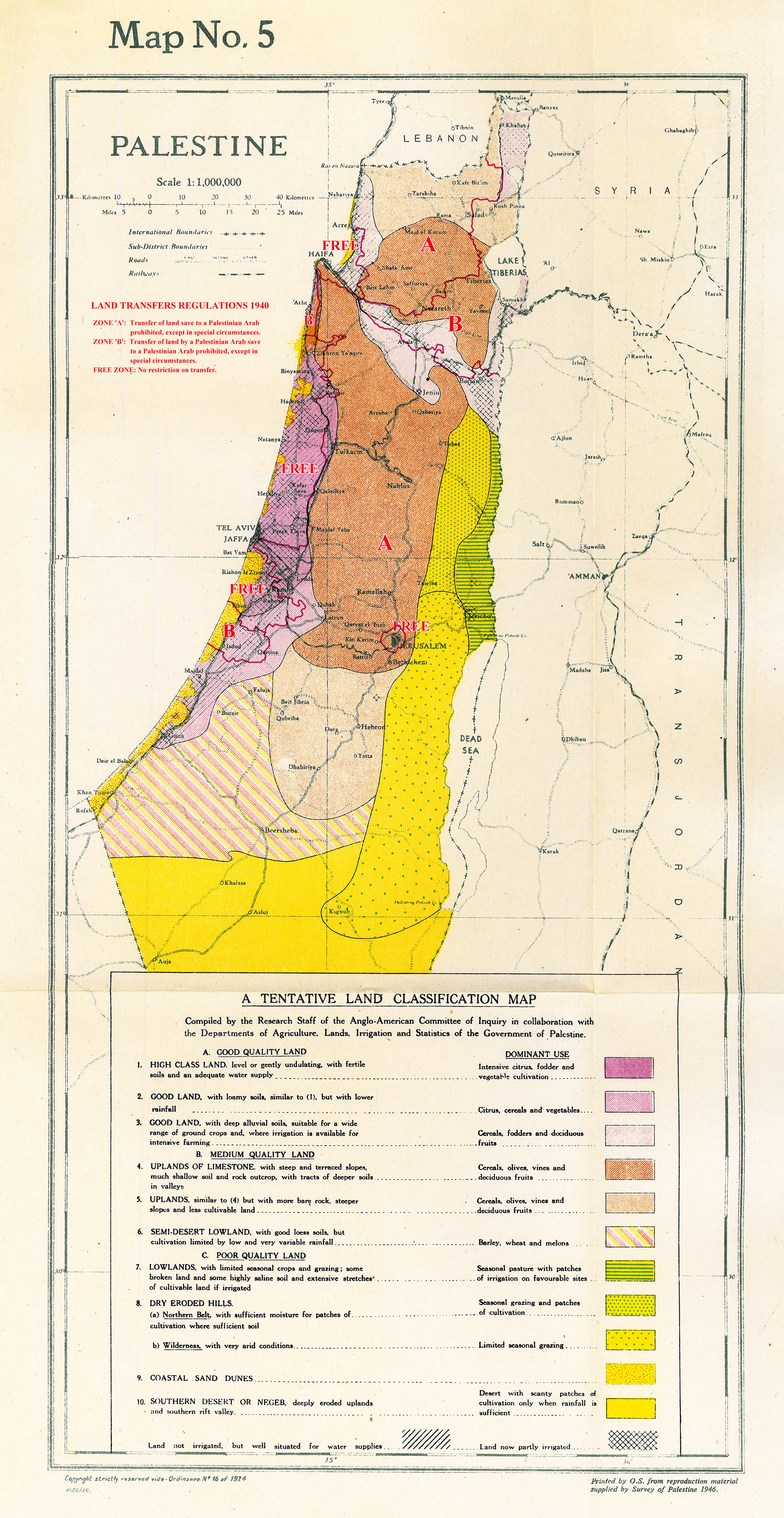

In February 1940, the British Government of Palestine promulgated the ''Land Transfer Regulations'' which divided Palestine into three regions with different restrictions on land sales applying to each. In Zone "A", which included the hill-country of Judea as a whole, certain areas in the

* Land Transfer Ordinance of 1920

* 1926 Correction of Land Registers Ordinance

* Land Settlement Ordinance of 1928

* Land Transfer Regulations of 1940

In February 1940, the British Government of Palestine promulgated the ''Land Transfer Regulations'' which divided Palestine into three regions with different restrictions on land sales applying to each. In Zone "A", which included the hill-country of Judea as a whole, certain areas in the

In 1920, the majority of the approximately people in this multi-ethnic region were Arabic-speaking Muslims, including a Bedouin population (estimated at at the time of the 1922 census and concentrated in the Beersheba area and the region south and east of it), as well as Jews (who accounted for some 11% of the total) and smaller groups of

In 1920, the majority of the approximately people in this multi-ethnic region were Arabic-speaking Muslims, including a Bedouin population (estimated at at the time of the 1922 census and concentrated in the Beersheba area and the region south and east of it), as well as Jews (who accounted for some 11% of the total) and smaller groups of  There were no further censuses but statistics were maintained by counting births, deaths and migration. By the end of 1936 the total population was approximately 1,300,000, the Jews being estimated at 384,000. The Arabs had also increased their numbers rapidly, mainly as a result of the cessation of the military conscription imposed on the country by the Ottoman Empire, the campaign against malaria and a general improvement in health services. In absolute figures their increase exceeded that of the Jewish population, but proportionally, the latter had risen from 13 per cent of the total population at the census of 1922 to nearly 30 per cent at the end of 1936.

Some components such as illegal immigration could only be estimated approximately. The White Paper of 1939, which placed immigration restrictions on Jews, stated that the Jewish population "has risen to some " and was "approaching a third of the entire population of the country". In 1945, a demographic study showed that the population had grown to , comprising Muslims, Jews, Christians and people of other groups.

There were no further censuses but statistics were maintained by counting births, deaths and migration. By the end of 1936 the total population was approximately 1,300,000, the Jews being estimated at 384,000. The Arabs had also increased their numbers rapidly, mainly as a result of the cessation of the military conscription imposed on the country by the Ottoman Empire, the campaign against malaria and a general improvement in health services. In absolute figures their increase exceeded that of the Jewish population, but proportionally, the latter had risen from 13 per cent of the total population at the census of 1922 to nearly 30 per cent at the end of 1936.

Some components such as illegal immigration could only be estimated approximately. The White Paper of 1939, which placed immigration restrictions on Jews, stated that the Jewish population "has risen to some " and was "approaching a third of the entire population of the country". In 1945, a demographic study showed that the population had grown to , comprising Muslims, Jews, Christians and people of other groups.

The following table gives the religious demography of each of the 16

The following table gives the religious demography of each of the 16

Under the terms of the August 1922 Palestine Order in Council, the Mandate territory was divided into administrative regions known as

Under the terms of the August 1922 Palestine Order in Council, the Mandate territory was divided into administrative regions known as

File:Palestine-WW1-3.jpg, General Allenby's final attacks of the Palestine Campaign gave Britain control of the area.

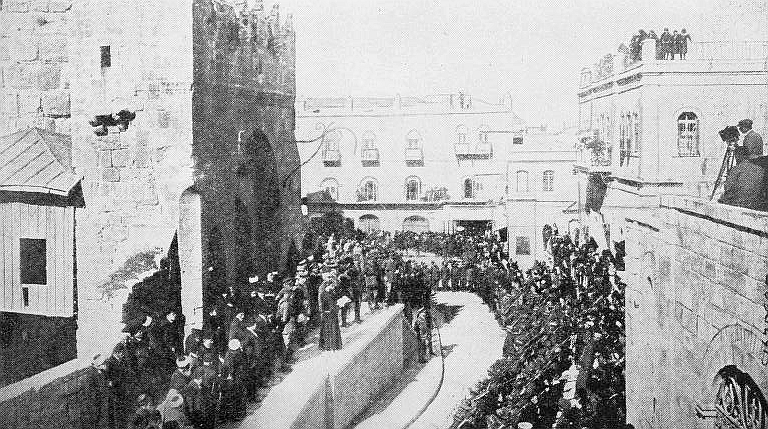

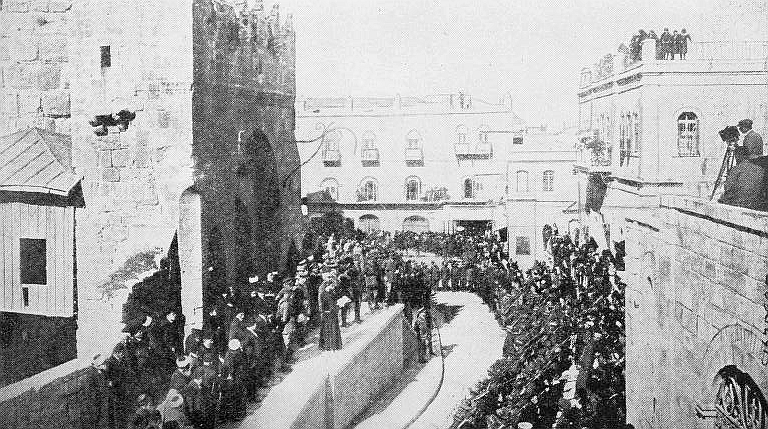

File:Field Marshal Allenby British troops Jerusalem dec 11 1917.jpg, Field Marshal Allenby entering Jerusalem with British troops on 11 December 1917

File:Big Gen Watson Mayor Jerusalem Dec 1917.jpg, General Watson meeting with the Mayor of Jerusalem in December 1917

File:Ottoman surrender of Jerusalem restored.jpg, The surrender of Jerusalem by the Ottomans to the British on 9 December 1917 following the Battle of Jerusalem

File:GPO, Jerusalem.jpg, Main post office, Jaffa Road, Jerusalem

File:Rockefeller Tower Jerusalem.jpg, The Rockefeller Museum, built in Jerusalem during the British Mandate

File:Central Post Office in Yaffo.JPG, Main post office,

online

* Cohen, Michael J. ''Britain's Moment in Palestine: Retrospect and Perspectives, 1917–1948'' (2014) * El-Eini, Roza. ''Mandated landscape: British imperial rule in Palestine 1929–1948'' (Routledge, 2004). * Galnoor, Itzhak. ''Partition of Palestine, The: Decision Crossroads in the Zionist Movement'' (SUNY Press, 2012). * Hanna, Paul Lamont,

British Policy in Palestine

", Washington, D.C., American Council on Public Affairs, (1942) * Harris, Kenneth. '' Attlee'' (1982) pp 388–400. * Kamel, Lorenzo. "Whose Land? Land Tenure in Late Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Palestine", "British Journal of Middle Eastern studies" (April 2014), 41, 2, pp. 230–242. * Miller, Rory, ed. ''Britain, Palestine and Empire: The Mandate Years'' (2010) * Morgan, Kenneth O.''The People's Peace: British history 1945 – 1990'' (1992) 49–52. * Ravndal, Ellen Jenny. "Exit Britain: British Withdrawal From the Palestine Mandate in the Early Cold War, 1947–1948," ''Diplomacy and Statecraft,'' (Sept 2010) 21#3 pp. 416–433. * Roberts, Nicholas E. "Re‐Remembering the Mandate: Historiographical Debates and Revisionist History in the Study of British Palestine." ''History Compass'' 9.3 (2011): 215–230

online

* Sargent, Andrew. " The British Labour Party and Palestine 1917–1949" (PhD thesis, University of Nottingham, 1980

online

* Shelef, Nadav G. "From 'Both Banks of the Jordan' to the 'Whole Land of Israel:' Ideological Change in Revisionist Zionism." ''Israel Studies'' 9.1 (2004): 125–148

Online

* Sinanoglou, Penny. "British Plans for the Partition of Palestine, 1929–1938." ''Historical Journal'' 52.1 (2009): 131–152

online

* Wright, Quincy, ''The Palestine Problem'', Political Science Quarterly, 41#3 (1926), pp. 384–412

online

.

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isra ...

) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 in the region of Palestine under the terms of the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. The manda ...

.

During the First World War (1914–1918), an Arab uprising against Ottoman rule and the British Empire's Egyptian Expeditionary Force under General Edmund Allenby drove the Ottoman Turks out of the Levant during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. The United Kingdom had agreed in the McMahon–Hussein Correspondence that it would honour Arab independence if the Arabs revolted against the Ottoman Turks, but the two sides had different interpretations of this agreement, and in the end, the United Kingdom and France divided the area under the Sykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, to define their mutually agreed Sphere of influence, spheres of influence and control in a ...

an act of betrayal in the eyes of the Arabs.

Further complicating the issue was the Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

of 1917, promising British support for a Jewish "national home" in Palestine. At the war's end the British and French formed a joint " Occupied Enemy Territory Administration" in what had been Ottoman Syria

Ottoman Syria ( ar, سوريا العثمانية) refers to divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of Syria, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Arabian Desert and south ...

. The British achieved legitimacy by obtaining a mandate from the League of Nations in June 1922. One objective of the League of Nations mandate system was to administer areas of the defunct Ottoman Empire "until such time as they are able to stand alone".

During the Mandate, the area saw the rise of nationalist movements

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

in both the Jewish and Arab communities. Competing interests of the two populations led to the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, later known as The Great Revolt (''al-Thawra al- Kubra'') or The Great Palestinian Revolt (''Thawrat Filastin al-Kubra''), was a popular nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine a ...

and the 1944–1948 Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine. The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, passed in November 1947, was met with Arab rejection. The 1947–1949 Palestine war

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. It is known in Israel as the War of Independence ( he, מלחמת העצמאות, ''Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut'') and ...

ended with the territory of Mandatory Palestine divided among the State of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, which annexed territory on the West Bank of the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

, and the Kingdom of Egypt, which established the "All-Palestine Protectorate

The All-Palestine Protectorate, or simply All-Palestine, also known as Gaza Protectorate and Gaza Strip, was a short-lived client state with limited recognition, corresponding to the area of the modern Gaza Strip, that was established in the area ...

" in the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

.

Name

The name given to the Mandate's territory was "Palestine", in accordance with local Palestinian Arab and Ottoman usage as well as European traditions. The Mandate charter stipulated that Mandatory Palestine would have three official languages, namely English, Arabic and Hebrew. In 1926, the British authorities formally decided to use the traditional Arabic and Hebrew equivalents to the English name, i.e. ''filasţīn'' (فلسطين) and ''pālēśtīnā'' (פּלשׂתינה) respectively. The Jewish leadership proposed that the proper Hebrew name should be ''ʾĒrēts Yiśrāʾel'' (ארץ ישׂראל,Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isra ...

). The final compromise was to add the initials of the Hebrew proposed name, Alef

Aleph (or alef or alif, transliterated ʾ) is the first letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician , Hebrew , Aramaic , Syriac , Arabic ʾ and North Arabian 𐪑. It also appears as South Arabian 𐩱 and Ge'ez .

These letter ...

- Yud, within parenthesis (א״י), whenever the Mandate's name was mentioned in Hebrew in official documents. The Arab leadership saw this compromise as a violation of the mandate terms. Some Arab politicians suggested " Southern Syria" (سوريا الجنوبية) as the Arabic name instead. The British authorities rejected this proposal; according to the Minutes of the Ninth Session of the League of Nations' Permanent Mandates Commission:

The adjective " Mandatory" indicates that the entity's legal status derived from a League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administ ...

; it is not related to the word's more commonplace usage as a synonym for "compulsory" or "necessary".

History

1920s

Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

. Concurrently, the Zionist Commission formed in March 1918 and became active in promoting Zionist objectives in Palestine. On 19 April 1920, elections took place for the Assembly of Representatives of the Palestinian Jewish community.

In March 1920, there was an attack

Attack may refer to:

Warfare and combat

* Offensive (military)

* Charge (warfare)

* Attack (fencing)

* Strike (attack)

* Attack (computing)

* Attack aircraft

Books and publishing

* ''The Attack'' (novel), a book

* '' Attack No. 1'', comic an ...

by Arabs on the Jewish village of Tel Hai. In April, there was another attack

Attack may refer to:

Warfare and combat

* Offensive (military)

* Charge (warfare)

* Attack (fencing)

* Strike (attack)

* Attack (computing)

* Attack aircraft

Books and publishing

* ''The Attack'' (novel), a book

* '' Attack No. 1'', comic an ...

on Jews, this time in Jerusalem.

In July 1920 a British civilian administration headed by a High Commissioner replaced the military administration. The first High Commissioner, Herbert Samuel, a Zionist and a recent British cabinet minister, arrived in Palestine on 20 June 1920 to take up his appointment from 1 July.

One of the first actions of the newly installed civil administration was to begin granting concessions from the Mandatory government over key economic assets. In 1921 the government granted Pinhas Rutenberg – a Jewish entrepreneur – concessions for the production and distribution of electrical power. Rutenberg soon established an electric company whose shareholders were Zionist organisations, investors, and philanthropists. Palestinian-Arabs saw it as proof that the British intended to favour Zionism. The British administration claimed that electrification would enhance the economic development of the country as a whole, while at the same time securing their commitment to facilitate a Jewish National Home through economicrather than politicalmeans.

In May 1921, almost 100 died in rioting in Jaffa after a disturbance between rival Jewish left-wing protestors was followed by attacks by Arabs on Jews.

Samuel tried to establish self-governing institutions in Palestine, as required by the mandate, but the Arab leadership refused to co-operate with any institution which included Jewish participation. When Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

One of the first actions of the newly installed civil administration was to begin granting concessions from the Mandatory government over key economic assets. In 1921 the government granted Pinhas Rutenberg – a Jewish entrepreneur – concessions for the production and distribution of electrical power. Rutenberg soon established an electric company whose shareholders were Zionist organisations, investors, and philanthropists. Palestinian-Arabs saw it as proof that the British intended to favour Zionism. The British administration claimed that electrification would enhance the economic development of the country as a whole, while at the same time securing their commitment to facilitate a Jewish National Home through economicrather than politicalmeans.

In May 1921, almost 100 died in rioting in Jaffa after a disturbance between rival Jewish left-wing protestors was followed by attacks by Arabs on Jews.

Samuel tried to establish self-governing institutions in Palestine, as required by the mandate, but the Arab leadership refused to co-operate with any institution which included Jewish participation. When Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Kamil al-Husayni

Kamil al-Husayni ( ar, كامل الحسيني, also spelled Kamel al-Hussaini; 23 February 1867 – 31 March 1921) was a Sunni Muslim religious leader in Palestine and member of the al-Husayni family. He was the Hanafi Mufti of Jerusalem from 1 ...

died in March 1921, High Commissioner Samuel appointed his half-brother Mohammad Amin al-Husseini to the position. Amin al-Husseini, a member of the al-Husayni clan of Jerusalem, was an Arab nationalist

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

and Muslim leader. As Grand Mufti, as well as in the other influential positions that he held during this period, al-Husseini played a key role in violent opposition to Zionism. In 1922, al-Husseini was elected President of the Supreme Muslim Council which had been established by Samuel in December 1921. The Council controlled the Waqf funds, worth annually tens of thousands of pounds and the orphan funds, worth annually about £50,000, as compared to the £600,000 in the Jewish Agency's annual budget. In addition, he controlled the Islamic

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the mai ...

courts in Palestine. Among other functions, these courts had the power to appoint teachers and preachers.

The 1922 Palestine Order in Council established a Legislative Council, which was to consist of 23 members: 12 elected, 10 appointed, and the High Commissioner. Of the 12 elected members, eight were to be Muslim Arabs, two Christian Arabs, and two Jews.Legislative Council (Palestine)Answers.com Arabs protested against the distribution of the seats, arguing that as they constituted 88% of the population, having only 43% of the seats was unfair. Elections took place in February and March 1923, but due to an Arab

boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

, the results were annulled and a 12-member Advisory Council was established."Palestine. The Constitution Suspended. Arab Boycott Of Elections. Back To British Rule" ''The Times'', 30 May 1923, p. 14, Issue 43354

At the First World Congress of Jewish Women

The First World Congress of Jewish Women was held in Vienna, Austria, from 6 to 11 May 1923. It brought together some 200 delegates from over 20 countries. Zionism was a prominent topic, while emigration to Palestine for Jewish refugees was discuss ...

which was held in Vienna, Austria, 1923, it was decided that: "It appears, therefore, to be the duty of all Jews to co-operate in the social-economic reconstruction of Palestine and to assist in the settlement of Jews in that country."

In October 1923, Britain provided the League of Nations with a report on the administration of Palestine for the period 1920–1922, which covered the period before the mandate.

In August 1929, there were riots

A riot is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The property targeted ...

in which 250 people died.

1930s: Arab armed insurgency

In 1930, Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam arrived in Palestine from Syria and organized and established theBlack Hand

Black Hand or The Black Hand may refer to:

Extortionists and underground groups

* Black Hand (anarchism) (''La Mano Negra''), a presumed secret, anarchist organization based in the Andalusian region of Spain during the early 1880s

* Black Hand ...

, an anti-Zionist

Anti-Zionism is opposition to Zionism. Although anti-Zionism is a heterogeneous phenomenon, all its proponents agree that the creation of the modern State of Israel, and the movement to create a sovereign Jewish state in the region of Palestine ...

and anti-British militant organization. He recruited and arranged military training for peasants, and by 1935 he had enlisted between 200 and 800 men. They used bombs and firearms against Zionist settlers and vandalized settlers' orchards and British-built railway lines. In November 1935, two of his men engaged in a firefight with a Palestine police patrol hunting fruit thieves and a policeman was killed. Following the incident, British police launched a search and surrounded al-Qassam in a cave near Ya'bad. In the ensuing battle, al-Qassam was killed.

The Arab revolt

The death of al-Qassam on 20 November 1935 generated widespread outrage in the Arab community. Huge crowds accompanied Qassam's body to his grave in Haifa. A few months later, in April 1936, the Arab national

The death of al-Qassam on 20 November 1935 generated widespread outrage in the Arab community. Huge crowds accompanied Qassam's body to his grave in Haifa. A few months later, in April 1936, the Arab national general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

broke out. The strike lasted until October 1936, instigated by the Arab Higher Committee, headed by Amin al-Husseini. During the summer of that year, thousands of Jewish-farmed acres and orchards were destroyed. Jewish civilians were attacked and killed, and some Jewish communities, such as those in Beisan

Beit She'an ( he, בֵּית שְׁאָן '), also Beth-shean, formerly Beisan ( ar, بيسان ), is a town in the Northern District of Israel. The town lies at the Beit She'an Valley about 120 m (394 feet) below sea level.

Beit She'an is be ...

( Beit She'an) and Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

, fled to safer areas. The violence abated for about a year while the British sent the Peel Commission to investigate.

During the first stages of the Arab Revolt, due to rivalry between the clans of al-Husseini and Nashashibi among the Palestinian Arabs, Raghib Nashashibi was forced to flee to Egypt after several assassination attempts ordered by Amin al-Husseini.

After the Arab rejection of the Peel Commission recommendation, the revolt resumed in autumn 1937. Over the next 18 months, the British lost Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

and Hebron. British forces, supported by 6,000 armed Jewish auxiliary police, suppressed the widespread riots with overwhelming force. The British officer Charles Orde Wingate

Major General Orde Charles Wingate, (26 February 1903 – 24 March 1944) was a senior British Army officer known for his creation of the Chindit deep-penetration missions in Japanese-held territory during the Burma Campaign of the Second World ...

(who supported a Zionist revival for religious reasons) organised Special Night Squads

The Special Night Squads (SNS) (Hebrew: ''Plagot Ha'Layla Ha'Meyukhadot'', פלוגות הלילה המיוחדות) was a joint British-Jewish counter-insurgency military unit, established by Captain Orde Wingate in Mandatory Palestine in 1938 ...

composed of British soldiers and Jewish volunteers such as Yigal Alon, which "scored significant successes against the Arab rebels in the lower Galilee and in the Jezreel valley" by conducting raids on Arab villages. The Jewish militia Irgun used violence also against Arab civilians as "retaliatory acts", attacking marketplaces and buses.

By the time the revolt concluded in March 1939, more than Arabs, 400 Jews, and 200 British had been killed and at least Arabs were wounded. In total, 10% of the adult Arab male population was killed, wounded, imprisoned, or exiled. From 1936 to 1945, while establishing collaborative security arrangements with the Jewish Agency, the British confiscated firearms from Arabs and 521 weapons from Jews.

The attacks on the Jewish population by Arabs had three lasting effects: firstly, they led to the formation and development of Jewish underground militias, primarily the Haganah, which were to prove decisive in 1948. Secondly, it became clear that the two communities could not be reconciled, and the idea of partition was born. Thirdly, the British responded to Arab opposition with the White Paper of 1939, which severely restricted Jewish land purchase and immigration. However, with the advent of World War II, even this reduced immigration quota was not reached. The White Paper policy itself radicalised segments of the Jewish population, who after the war would no longer cooperate with the British.

The revolt had also a negative effect on Palestinian Arab leadership, social cohesion, and military capabilities and contributed to the outcome of the 1948 War because "when the Palestinians faced their most fateful challenge in 1947–49, they were still suffering from the British repression of 1936–39, and were in effect without a unified leadership. Indeed, it might be argued that they were virtually without any leadership at all."

Partition proposals

In 1937, the Peel Commission proposed a partition between a small Jewish state, whose Arab population would have to be transferred, and an Arab state to be attached to Jordan. The proposal was rejected outright by the Arabs. The two main Jewish leaders, Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion, had convinced the Zionist Congress to approve equivocally the Peel recommendations as a basis for more negotiation.Louis, William Roger (2006)''Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization''

, p. 391.Morris, Benny (2009). ''One State, Two States: Resolving the Israel/Palestine Conflict'', p. 66 p. 11 "while the Zionist movement, after much agonising, accepted the principle of partition and the proposals as a basis for negotiation"; p. 49 "In the end, after bitter debate, the Congress equivocally approved—by a vote of 299 to 160—the Peel recommendations as a basis for further negotiation." In a letter to his son in October 1937, Ben-Gurion explained that partition would be a first step to "possession of the land as a whole". The same sentiment was recorded by Ben-Gurion on other occasions, such as at a meeting of the Jewish Agency executive in June 1938, as well as by Chaim Weizmann. Following the London Conference (1939) the British Government published a White Paper which proposed a limit to Jewish immigration from Europe, restrictions on Jewish land purchases, and a program for creating an independent state to replace the Mandate within ten years. This was seen by the Yishuv as betrayal of the mandatory terms, especially in light of the increasing persecution of Jews in Europe. In response, Zionists organised '' Aliyah Bet'', a program of illegal immigration into Palestine.

Lehi

Lehi (; he, לח"י – לוחמי חרות ישראל ''Lohamei Herut Israel – Lehi'', "Fighters for the Freedom of Israel – Lehi"), often known pejoratively as the Stern Gang,"This group was known to its friends as LEHI and to its enemie ...

, a small group of extremist Zionists, staged armed attacks on British authorities in Palestine. However, the Jewish Agency, which represented the mainstream Zionist leadership and most of the Jewish population, still hoped to persuade Britain to allow resumed Jewish immigration, and cooperated with Britain in World War II.

World War II

Allied and Axis activity

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on the British Commonwealth and sided with Germany. Within a month, the Italians attacked Palestine from the air, bombing Tel Aviv and Haifa, inflicting multiple casualties. In 1942, there was a period of great concern for the Yishuv, when the forces of German GeneralErwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

advanced east across North Africa towards the Suez Canal

The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular ...

, raising fear that they would conquer Palestine. This period was referred to as the "200 days of dread

The 200 days of dread ( he, מאתיים ימי חרדה; ) was a period of 200 days (almost 7 months) in the history of the Yishuv in British Palestine, from the spring of 1942 to November 1942, when the German Afrika Korps under the command of ...

". This event was the direct cause for the founding, with British support, of the Palmach

The Palmach (Hebrew: , acronym for , ''Plugot Maḥatz'', "Strike Companies") was the elite fighting force of the Haganah, the underground army of the Yishuv (Jewish community) during the period of the British Mandate for Palestine. The Palmach ...

– a highly trained regular unit belonging to Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

(a paramilitary group composed mostly of reserves).

As in most of the Arab world, there was no unanimity amongst the Palestinian Arabs as to their position regarding the belligerents in World War II. A number of leaders and public figures saw an Axis victory as the likely outcome and a way of securing Palestine back from the Zionists and the British. Even though Arabs were not highly regarded by Nazi racial theory

The Nazi Party adopted and developed several pseudoscientific racial classifications as part of its ideology (Nazism) in order to justify the genocide of groups of people which it deemed racially inferior. The Nazis considered the putative "Ar ...

, the Nazis encouraged Arab support as a counter to British hegemony. On the anniversary of the Balfour Declaration in 1943, SS-Reichsfuehrer Heinrich Himmler and Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

sent telegrams of support for the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Mohammad Amin al-Husseini to read out for a radio broadcast to a rally of supporters in Berlin. On the other hand, as many as 12,000 Palestinian Arabs, with the endorsement of many prominent figures such as mayors of Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

and Gaza

Gaza may refer to:

Places Palestine

* Gaza Strip, a Palestinian territory on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea

** Gaza City, a city in the Gaza Strip

** Gaza Governorate, a governorate in the Gaza Strip Lebanon

* Ghazzeh, a village in ...

and media such as "Radio Palestine" and the prominent Jafa-based ''Falastin

''Falastin'' ( ar, فلسطين), meaning Palestine in Arabic, was an Arabic-language Palestinian newspaper. Founded in 1911 in Jaffa, ''Falastin'' began as a weekly publication, evolving into one of the most influential dailies in Ottoman and ...

'' newspaper at the time, volunteered to join and fight for the British, with many serving in units that also included Jews from Palestine. 120 Palestinian women also served as part of the "Auxiliary Territorial Service". However, this history has been less studied, as Israeli sources put more focus in studying the role played by Jewish soldiers, and Palestinian sources were wary of glorifying the idea of cooperating with the British only a few short years after the brutal British suppression of the 1936–1939 Arab revolt.Aderet, Ofer. "12,000 Palestinians Fought for U.K. in WWII alongside Jewish Volunteers, Historian Finds." Haaretz.com. Haaretz, May 31, 2019Link

.

Mobilisation

On 3 July 1944, the British government consented to the establishment of a Jewish Brigade, with hand-picked Jewish and also non-Jewish senior officers. On 20 September 1944, an official communiqué by the War Office announced the formation of the Jewish Brigade Group of the British Army. The Jewish brigade then was stationed in Tarvisio, near the border triangle of Italy, Yugoslavia, and Austria, where it played a key role in the Berihah's efforts to help Jews escape Europe for Palestine, a role many of its members would continue after the brigade was disbanded. Among its projects was the education and care of the Selvino children. Later, veterans of the Jewish Brigade became key participants of the newState of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

's Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

.

From the Palestine Regiment, two platoons, one Jewish, under the command of Brigadier Ernest Benjamin, and another Arab were sent to join Allied forces on the Italian Front, having taken part in the final offensive there.

Besides Jews and Arabs from Palestine, in total by mid-1944 the British had assembled a multiethnic force consisting of volunteer European Jewish refugees (from German-occupied countries), Yemenite Jews and Abyssinian Jews.

The Holocaust and immigration quotas

In 1939, as a consequence of the White Paper of 1939, the British reduced the number of immigrants allowed into Palestine. World War II and the Holocaust started shortly thereafter and once the 15,000 annual quota was exceeded, Jews fleeing Nazi persecution were interned in detention camps or deported to places such as Mauritius. Starting in 1939, a clandestine immigration effort called Aliya Bet was spearheaded by an organisation called Mossad LeAliyah Bet. Tens of thousands of European Jews escaped the Nazis in boats and small ships headed for Palestine. The Royal Navy intercepted many of the vessels; others were unseaworthy and were wrecked; aHaganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

bomb sunk the , killing 267 people; two other ships were sunk by Soviet submarines: the motor schooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

was torpedoed and sunk in the Black Sea by a Soviet submarine in February 1942 with the loss of nearly 800 lives. The last refugee boats to try to reach Palestine during the war were the ''Bulbul'', and ''Morina'' in August 1944. A Soviet submarine sank the motor schooner ''Mefküre'' by torpedo and shellfire and machine-gunned survivors in the water, killing between 300 and 400 refugees. Illegal immigration resumed after World War II.

After the war 250,000 Jewish refugees were stranded in displaced persons (DP) camps in Europe. Despite the pressure of world opinion, in particular the repeated requests of US President Harry S. Truman and the recommendations of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry

The Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry was a joint British and American committee assembled in Washington, D.C. on 4 January 1946. The committee was tasked to examine political, economic and social conditions in Mandatory Palestine and the well- ...

that 100,000 Jews be immediately granted entry to Palestine, the British maintained the ban on immigration.

Beginning of Zionist insurgency

The Jewish Lehi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel) and Irgun (National Military Organisation) movements initiated violent uprisings against the British Mandate in the 1940s. On 6 November 1944, Eliyahu Hakim and Eliyahu Bet Zuri (members of Lehi) assassinated Lord Moyne in Cairo. Moyne was the British Minister of State for the Middle East and the assassination is said by some to have turned British Prime Minister

The Jewish Lehi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel) and Irgun (National Military Organisation) movements initiated violent uprisings against the British Mandate in the 1940s. On 6 November 1944, Eliyahu Hakim and Eliyahu Bet Zuri (members of Lehi) assassinated Lord Moyne in Cairo. Moyne was the British Minister of State for the Middle East and the assassination is said by some to have turned British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

against the Zionist cause. After the assassination of Lord Moyne, the Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

kidnapped, interrogated, and turned over to the British many members of the Irgun ("The Hunting Season

The Saison (Hunting Season) ( he, הסזון, links=no, short for ) was the name given to the Haganah's attempt, as ordered by the official bodies of the pre-state Yishuv, to suppress the Irgun's insurgency against the government of the British ...

"), and the Jewish Agency Executive decided on a series of measures against "terrorist organisations" in Palestine. Irgun ordered its members not to resist or retaliate with violence, so as to prevent a civil war.

After World War II: Insurgency and the Partition Plan

The three main Jewish underground forces later united to form the Jewish Resistance Movement and carry out several attacks and bombings against the British administration. In 1946, the Irgun blew up the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, the southern wing of which was the headquarters of the British administration, killing 92 people. Following the bombing, the British Government began interning illegal Jewish immigrants in Cyprus. In 1948 the Lehi assassinated the UN mediator Count Bernadotte in Jerusalem. Yitzak Shamir, future prime minister of Israel was one of the conspirators.Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry

The Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry was a joint British and American committee assembled in Washington, D.C. on 4 January 1946. The committee was tasked to examine political, economic and social conditions in Mandatory Palestine and the well- ...

in 1946 was a joint attempt by Britain and the United States to agree on a policy regarding the admission of Jews to Palestine. In April, the Committee reported that its members had arrived at a unanimous decision. The Committee approved the American recommendation of the immediate acceptance of 100,000 Jewish refugees from Europe into Palestine. It also recommended that there be no Arab, and no Jewish State. The Committee stated that "in order to dispose, once and for all, of the exclusive claims of Jews and Arabs to Palestine, we regard it as essential that a clear statement of principle should be made that Jew shall not dominate Arab and Arab shall not dominate Jew in Palestine". US President Harry S Truman angered the British Government by issuing a statement supporting the 100,000 refugees but refusing to acknowledge the rest of the committee's findings. Britain had asked for U.S assistance in implementing the recommendations. The US War Department had said earlier that to assist Britain in maintaining order against an Arab revolt, an open-ended US commitment of 300,000 troops would be necessary. The immediate admission of 100,000 new Jewish immigrants would almost certainly have provoked an Arab uprising.

These events were the decisive factors that forced Britain to announce their desire to terminate the Palestine Mandate and place the Question of Palestine before the United Nations, the successor to the League of Nations. The UN created UNSCOP (the UN Special Committee on Palestine) on 15 May 1947, with representatives from 11 countries. UNSCOP conducted hearings and made a general survey of the situation in Palestine, and issued its report on 31 August. Seven members (Canada, Czechoslovakia, Guatemala, Netherlands, Peru, Sweden, and Uruguay) recommended the creation of independent Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem to be placed under international administration. Three members (India, Iran, and Yugoslavia) supported the creation of a single federal state containing both Jewish and Arab constituent states. Australia abstained.

}

On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly, voting 33 to 13, with 10 abstentions, adopted a resolution recommending the adoption and implementation of the ''Plan of Partition with Economic Union'' as Resolution 181 (II), while making some adjustments to the boundaries between the two states proposed by it. The division was to take effect on the date of British withdrawal. The partition plan required that the proposed states grant full civil rights to all people within their borders, regardless of race, religion or gender. The UN General Assembly is only granted the power to make recommendations; therefore, UNGAR 181 was not legally binding. Both the US and the Soviet Union supported the resolution. Haiti, Liberia, and the Philippines changed their votes at the last moment after concerted pressure from the US and from Zionist organisations. The five members of the Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

, who were voting members at the time, voted against the Plan.

The Jewish Agency, which was the Jewish state-in-formation, accepted the plan, and nearly all the Jews in Palestine rejoiced at the news.

The partition plan was rejected by Palestinian Arab leadership and by most of the Arab population. Meeting in Cairo on November and December 1947, the Arab League then adopted a series of resolutions endorsing a military solution to the conflict.

Britain announced that it would accept the partition plan, but refused to enforce it, arguing it was not accepted by the Arabs. Britain also refused to share the administration of Palestine with the UN Palestine Commission during the transitional period. In September 1947, the British government announced that the Mandate for Palestine would end at midnight on 14 May 1948."Palestine"Encyclopædia Britannica Online School Edition, 2006. 15 May 2006. Some Jewish organisations also opposed the proposal. Irgun leader

Menachem Begin

Menachem Begin ( ''Menaḥem Begin'' (); pl, Menachem Begin (Polish documents, 1931–1937); ''Menakhem Volfovich Begin''; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of Likud and the sixth Prime Minister of Israel. B ...

announced, "The partition of the Homeland is illegal. It will never be recognised. The signature by institutions and individuals of the partition agreement is invalid. It will not bind the Jewish people. Jerusalem was and will forever be our capital. Eretz Israel will be restored to the people of Israel. All of it. And for ever."

Termination of the mandate

When the UK announced the independence of Transjordan in 1946, the final Assembly of the League of Nations and the General Assembly both adopted resolutions welcoming the news. The Jewish Agency objected, claiming that Transjordan was an integral part of Palestine, and that according to Article 80 of the UN Charter, the Jewish people had a secured interest in its territory.

During the General Assembly deliberations on Palestine, there were suggestions that it would be desirable to incorporate part of Transjordan's territory into the proposed Jewish state. A few days before the adoption of Resolution 181 (II) on 29 November 1947, US Secretary of State Marshall noted frequent references had been made by the Ad Hoc Committee regarding the desirability of the Jewish State having both the Negev and an "outlet to the Red Sea and the Port of Aqaba". According to John Snetsinger, Chaim Weizmann visited President Truman on 19 November 1947 and said it was imperative that the Negev and Port of Aqaba be within the Jewish state. Truman telephoned the US delegation to the UN and told them he supported Weizmann's position. However, the Trans-Jordan memorandum excluded territories of the Emirate of Transjordan from any Jewish settlement.

Immediately after the UN resolution, the 1947-1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine broke out between the Arab and Jewish communities, and British authority began to break down. On 16 December 1947, the Palestine Police Force withdrew from the Tel Aviv area, home to more than half the Jewish population, and turned over responsibility for the maintenance of law and order to Jewish police. As the civil war raged on, British military forces gradually withdrew from Palestine, although they occasionally intervened in favour of either side. Many of these areas became war zones. The British maintained strong presences in Jerusalem and Haifa, even as Jerusalem came under siege by Arab forces and became the scene of fierce fighting, though the British occasionally intervened in the fighting, largely to secure their evacuation routes, including by proclaiming martial law and enforcing truces. The Palestine Police Force was largely inoperative, and government services such as social welfare, water supplies, and postal services were withdrawn. In March 1948, all British judges in Palestine were sent back to Britain. In April 1948, the British withdrew from most of Haifa but retained an enclave in the port area to be used in the evacuation of British forces, and retained

When the UK announced the independence of Transjordan in 1946, the final Assembly of the League of Nations and the General Assembly both adopted resolutions welcoming the news. The Jewish Agency objected, claiming that Transjordan was an integral part of Palestine, and that according to Article 80 of the UN Charter, the Jewish people had a secured interest in its territory.

During the General Assembly deliberations on Palestine, there were suggestions that it would be desirable to incorporate part of Transjordan's territory into the proposed Jewish state. A few days before the adoption of Resolution 181 (II) on 29 November 1947, US Secretary of State Marshall noted frequent references had been made by the Ad Hoc Committee regarding the desirability of the Jewish State having both the Negev and an "outlet to the Red Sea and the Port of Aqaba". According to John Snetsinger, Chaim Weizmann visited President Truman on 19 November 1947 and said it was imperative that the Negev and Port of Aqaba be within the Jewish state. Truman telephoned the US delegation to the UN and told them he supported Weizmann's position. However, the Trans-Jordan memorandum excluded territories of the Emirate of Transjordan from any Jewish settlement.

Immediately after the UN resolution, the 1947-1948 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine broke out between the Arab and Jewish communities, and British authority began to break down. On 16 December 1947, the Palestine Police Force withdrew from the Tel Aviv area, home to more than half the Jewish population, and turned over responsibility for the maintenance of law and order to Jewish police. As the civil war raged on, British military forces gradually withdrew from Palestine, although they occasionally intervened in favour of either side. Many of these areas became war zones. The British maintained strong presences in Jerusalem and Haifa, even as Jerusalem came under siege by Arab forces and became the scene of fierce fighting, though the British occasionally intervened in the fighting, largely to secure their evacuation routes, including by proclaiming martial law and enforcing truces. The Palestine Police Force was largely inoperative, and government services such as social welfare, water supplies, and postal services were withdrawn. In March 1948, all British judges in Palestine were sent back to Britain. In April 1948, the British withdrew from most of Haifa but retained an enclave in the port area to be used in the evacuation of British forces, and retained RAF Ramat David

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

, an airbase close to Haifa, to cover their retreat, leaving behind a volunteer police force to maintain order. The city was quickly captured by the Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

in the Battle of Haifa. After the victory, British forces in Jerusalem announced that they had no intention of overseeing any local administration but also that they would not permit actions that would hamper the safe and orderly withdrawal of their forces; military courts would try anybody who interfered. Although by this time British authority in most of Palestine had broken down, with most of the country in the hands of Jews or Arabs, the British air and sea blockade of Palestine remained in place. Although Arab volunteers were able to cross the borders between Palestine and the surrounding Arab states to join the fighting, the British did not allow the regular armies of the surrounding Arab states to cross into Palestine.

The British had notified the UN of their intent to terminate the mandate not later than 1 August 1948. However, early in 1948, the United Kingdom announced its firm intention to end its mandate in Palestine on 15 May. In response, President Harry S Truman made a statement on 25 March proposing UN trusteeship rather than partition, stating that "unfortunately, it has become clear that the partition plan cannot be carried out at this time by peaceful means... unless emergency action is taken, there will be no public authority in Palestine on that date capable of preserving law and order. Violence and bloodshed will descend upon the Holy Land. Large-scale fighting among the people of that country will be the inevitable result". The British Parliament passed the necessary legislation to terminate the Mandate with the Palestine Bill, which received Royal assent on 29 April 1948.

By 14 May 1948, the only British forces remaining in Palestine were in the Haifa area and in Jerusalem. On that same day, the British garrison in Jerusalem withdrew, and High Commissioner Alan Cunningham

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Alan Gordon Cunningham, (1 May 1887 – 30 January 1983) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the British Army noted for his victories over Italian forces in the East African Campaign (World War ...

left the city for Haifa, where he was to leave the country by sea. The Jewish leadership, led by future Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, declared the establishment of a Jewish State in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, on the afternoon of 14 May 1948 (5 Iyar 5708 in the Hebrew calendar), to come into force at midnight of that day. On the same day, the Provisional Government of Israel asked the US Government for recognition, on the frontiers specified in the UN Plan for Partition. The United States immediately replied, recognizing "the provisional government as the de facto authority".

At midnight on 14/15 May 1948, the Mandate for Palestine expired and the State of Israel came into being. The Palestine Government formally ceased to exist, the status of British forces still in the process of withdrawal from Haifa changed to occupiers of foreign territory, the Palestine Police Force formally stood down and was disbanded, with the remaining personnel evacuated alongside British military forces, the British blockade of Palestine was lifted, and all those who had been Palestinian citizens ceased to be British protected person

A British protected person (BPP) is a member of a class of British nationality associated with former protectorates, protected states, and territorial mandates and trusts under British control. Individuals with this nationality are British na ...

s, with Mandatory Palestine passports no longer giving British protection. The 1948 Palestinian exodus

In 1948 Estimates of the Palestinian Refugee flight of 1948, more than 700,000 Palestinians, Palestinian Arabs – about half of prewar Mandatory Palestine, Palestine's Arab population – Causes of the 1948 Palestinian exodus, were expelled ...

took place both before and after the end of the Mandate.Rashid (1997). p21

"In 1948 half of Palestine's 1.4 million Arabs were uprooted from their homes and became refugees". Over the next few days, approximately 700 Lebanese, 1,876 Syrian, 4,000 Iraqi, and 2,800 Egyptian troops crossed over the borders into Palestine, starting the

1948 Arab–Israeli War