Malaita Kingz F on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Malaita is the primary island of

Malaita's climate is extremely wet. It is located in the

Malaita's climate is extremely wet. It is located in the  Malaitan hydrology includes thousands of small springs, rivulets, and streams, characteristic of a young drainage pattern. At higher altitudes

Malaitan hydrology includes thousands of small springs, rivulets, and streams, characteristic of a young drainage pattern. At higher altitudes

Malaita Province

Malaita Province is the most populous and one of the largest of the nine provinces of Solomon Islands. It is named after its largest island, Malaita (also known as "Big Malaita" or "Maramapaina"). Other islands include South Malaita Island ...

in Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its capita ...

. Malaita is the most populous island of the Solomon Islands, with a population of 161,832 as of 2021, or more than a third of the entire national population. It is also the second largest island in the country by area, after Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the seco ...

. A tropical and mountainous island, Malaita's river systems and tropical forests are being exploited for ecosystem stability by keeping them pristine.

The largest city and provincial capital is Auki, on the northwest coast and is on the northern shore of the Langa Langa Lagoon. The people of the Langa Langa Lagoon and the Lau Lagoon on the northeast coast of Malaita call themselves ''wane i asi'' ‘salt-water people’ as distinct from ''wane i tolo'' ‘bush people’ who live in the interior of the island.

South Malaita Island

South Malaita Island is the island at the southern tip of the larger island of Malaita in the eastern part of the Solomon Islands. It is also known as Small Malaita and Maramasike for Areare speakers and Malamweimwei for more than 80% of the isla ...

, also known as ''Small Malaita'' and ''Maramasike'' for Areare speakers and Malamweimwei known to more than 80% of the islanders, is the island at the southern tip of the larger island of Malaita.

Name

Most local names for the island are Mala, or its dialect variants Mara or Mwala. The name Malaita or Malayta appears in the logbook of the Spanish explorers who in the 16th century visited the islands, and claimed that to be the actual name. They first saw the island from Santa Isabel, where it is called Mala. One theory is that "ita" was added on, as the Bughotu word for up or east, or in this context "there." BishopGeorge Augustus Selwyn

George Augustus Selwyn (5 April 1809 – 11 April 1878) was the first Anglican Bishop of New Zealand. He was Bishop of New Zealand (which included Melanesia) from 1841 to 1869. His diocese was then subdivided and Selwyn was Metropolitan (later ...

referred to it as Malanta in 1850. Mala was the name used under British control; now Malaita is used for official purposes. The name Big Malaita is also used to distinguish it from the smaller South Malaita Island

South Malaita Island is the island at the southern tip of the larger island of Malaita in the eastern part of the Solomon Islands. It is also known as Small Malaita and Maramasike for Areare speakers and Malamweimwei for more than 80% of the isla ...

.

History

Early settlement and European discovery

Malaita was, along with the other Solomon Islands, settled by Austronesian speakers between 5000 and 3500 years ago; the earlier Papuan speakers are thought to have only reached the western Solomon Islands. However, Malaita has not been archaeologically examined, and a chronology of its prehistory is difficult to establish. In the traditional account of theKwara'ae

The Kwara'ae language (previously called Fiu after the location of many of its speakers) is spoken in the north of Malaita Island in the Solomon Islands. In 1999, there were 32,400 people known to speak the language. It is the largest indigenous ...

, their founding ancestor arrived about twenty generations ago, landed first on Guadalcanal, but followed a magical staff which led him on to the middle of Malaita, where he established their cultural norms. His descendants then dispersed to the lowland areas on the edges of the island.

First recorded sighting by Europeans of Malaita was by the Spaniard Álvaro de Mendaña Álvaro (, , ) is a Spanish, Galician and Portuguese male given name and surname (see Spanish naming customs) of Visigothic origin. Some claim it may be related to the Old Norse name Alfarr, formed of the elements ''alf'' "elf" and ''arr'' "warrior ...

on 11 April 1568. More precisely the sighting was due to a local voyage done by a small boat, in the accounts the brigantine Santiago, commanded by Maestre de Campo Pedro Ortega Valencia and having Hernán Gallego as pilot. In his account, Gallego chief pilot of Mendaña's expedition, establishes that they called the island Malaita after its native name and explored much of the coast, though not the north side. The Maramasiki Passage was thought to be a river. At one point they were greeted with war canoe

A canoe is a lightweight narrow water vessel, typically pointed at both ends and open on top, propelled by one or more seated or kneeling paddlers facing the direction of travel and using a single-bladed paddle.

In British English, the term ...

s and fired at with arrow

An arrow is a fin-stabilized projectile launched by a bow. A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers c ...

s; they retaliated with shots and killed and wounded some. However, after this discovery, the entire Solomon Islands chain was not found, and even its existence doubted, for two hundred years.

Labour trade and missions

After it was re-discovered in the late 18th century, Malaitans were subjected to harsh treatment fromwhaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

boat crews and blackbirders

Blackbirding involves the coercion of people through deception or kidnapping to work as slaves or poorly paid labourers in countries distant from their native land. The term has been most commonly applied to the large-scale taking of people in ...

(labour recruiters). Contact with outsiders also brought new opportunities for education. The first Malaitans to learn to read and write were Joseph Wate and Watehou, who accompanied Bishop John Coleridge Patteson to St John's College, Auckland

The College of St John the Evangelist or St Johns Theological College, is the residential theological college of the Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia.

The site at Meadowbank in Auckland is the base for theological educatio ...

.

From the 1870s to 1903 Malaitan men (and some women) comprised the largest number of Solomon Islander Kanaka workers in the indentured labour trade to Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

, Australia and to Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

. The 1870s were a time of illegal recruiting practices known as blackbirding

Blackbirding involves the coercion of people through deception or kidnapping to work as slaves or poorly paid labourers in countries distant from their native land. The term has been most commonly applied to the large-scale taking of people in ...

. Malaitans are known to have volunteered as indentured labourers with some making their second trip to work on plantations, although the labour system remained exploitative. In 1901 the Commonwealth of Australia enacted the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901

The Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901 was an Act of the Parliament of Australia which was designed to facilitate the mass deportation of nearly all the Pacific Islanders (called "Kanakas") working in Australia, especially in the Queensland sugar ...

which facilitated the deportation of Pacific Islanders that was the precursor to the White Australia policy. However, many islanders remained and formed the South Sea Islander community of Australia. Many labourers that returned to Malaita had learnt to read and had become Christian. The skills of literacy and protest letters as to being deported from Australia was a precedent for the later Maasina Ruru

Maasina Ruru was an emancipation movement for self-government and self-determination in the British Solomon Islands during and after World War II, 1945–1950, credited with creating the movement towards independence for the Solomon Islands. The ...

movement.

Many of the earliest missionaries, both Catholic and Protestant, were killed, and this violent reputation survives in the geographic name of Cape Arsacides, the eastward bulge of the northern part of the island, meaning Cape of the Assassins. The cape was even mentioned in Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American people, American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his bes ...

's epic novel '' Moby Dick'' by Ishmael

Ishmael ''Ismaḗl''; Classical/Qur'anic Arabic: إِسْمَٰعِيْل; Modern Standard Arabic: إِسْمَاعِيْل ''ʾIsmāʿīl''; la, Ismael was the first son of Abraham, the common patriarch of the Abrahamic religions; and is cons ...

, the novel's narrator. Ishmael talks of his friendship with the fictional Tranquo, King of Tranque. However, some of the earliest missionaries were Malaitans who had worked abroad, such as Peter Ambuofa Peter Ambuofa was an early convert to Christianity among Solomon Islanders who established a Christian community on Malaita, and a key figure in the history of the South Seas Evangelical Mission (now South Seas Evangelical Church, SSEC).

Peter Amb ...

, who was baptised at Bundaberg, Queensland

Bundaberg is a city in the Bundaberg Region, Queensland, Australia, and is the List of places in Queensland by population, tenth largest city in the state. Bundaberg's Bundaberg Regional Council, regional area has a population of 70,921, and is ...

in 1892, and gathered a Christian community around him when he returned in 1894. In response to his appeals, Florence Young

Florence Selina Harriet Young (10 October 1856 – 28 May 1940) was a New Zealand-born missionary who established the Queensland Kanaka Mission in order to convert Kanaka labourers in Queensland, Australia. In addition, she conducted missionary ...

led the first party of the Queensland Kanaka Mission (the ancestor of the SSEC) to the Solomons in 1904. Anglican and Catholic churches also missionized at this point, and set up schools in areas such as Malu'u.

As the international labour trade slowed, an internal labour trade within the archipelago developed, and by the 1920s thousands of Malaitans worked on plantations on other islands.

Establishment of colonial power

At this time, there was no central power among the groups on Malaita, and there were numerous blood feuds, exacerbated by the introduction of Western guns, and steel tools which meant less time constraints for gardening. Around 1880,Kwaisulia

Kwaisulia (early 1850s – 1909) was a prominent tradesman, strongman and blackbirder on the island of Malaita in the late nineteenth century, who for several decades held political control over the north of the island.

Born on the island of Sulu ...

, one of the chiefs, negotiated with labour recruiters to receive a supply of weapons in exchange of workers, based on a similar negotiation made by a chief on the Shortland Islands; this weapon supply gave the chiefs considerable power. However, labour recruitment was not always smooth. In 1886, the vessel ''Young Dick'' was attacked at Sinerango, Malaita, and most of its crew murdered.Kent, 102. In 1886, Britain defined its area of interest in the Solomons, including Malaita, and central government control of Malaita began in 1893, when Captain Gibson R.N., of , declared the southern Solomon Islands as a British Protectorate with the proclamation of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, claiming to regulate the local warfare and unfair labour trade, although it coincided with the German acquisition of territories to the west and French interest in those to the east.

Auki was established as a government station in 1909, as headquarters of the administrative district of Malaita. The government began to pacify the island, registering or confiscating firearms, collecting a head tax, and breaking the power of unscrupulous war leaders. One important figure in the process was District Commissioner William R. Bell

William Robert Bell (7 August 1876 – 4 October 1927) was an Australian-born official in the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, who served as the District Officer of Malaita from 1915 until 1927. He was killed while collecting a head tax fro ...

, who was killed in 1927 by a Kwaio, along with a cadet named Lillies and 13 Solomon Islanders in his charge. A massive punitive expedition, known as the Malaita massacre, ensued; at least 60 Kwaio were killed, nearly 200 detained in Tulagi

Tulagi, less commonly known as Tulaghi, is a small island——in Solomon Islands, just off the south coast of Ngella Sule. The town of the same name on the island (pop. 1,750) was the capital of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate from 18 ...

(the protectorate capital), and many sacred sites and objects were destroyed or desecrated. Resentment about this incident continues, and in 1983 leaders from the Kwaio area council requested that the national government demand from the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

about $100 million in compensation for the incident. When the central government did not act on this request, the council encouraged a boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organization, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for moral, social, political, or environmental reasons. The purpose of a boycott is to inflict som ...

of the 1986 national elections.

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, which played a major role in Solomons history, did not have a major impact upon Malaita. Auki became the temporary capital when Tulagi

Tulagi, less commonly known as Tulaghi, is a small island——in Solomon Islands, just off the south coast of Ngella Sule. The town of the same name on the island (pop. 1,750) was the capital of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate from 18 ...

was seized by the Japanese, and it too was briefly raided by Japan, but little fighting happened on the island. Malaitans who fought in battalions, however, brought a new movement for self-determination known as Maasina Ruru

Maasina Ruru was an emancipation movement for self-government and self-determination in the British Solomon Islands during and after World War II, 1945–1950, credited with creating the movement towards independence for the Solomon Islands. The ...

(or "Marching Rule"), which spread quickly across the island. Participants united across traditional religious, ethnic, and clan lines, lived in fortified nontraditional villages, and refused to cooperate with the British.Ross, 58-59. The organization of the movement on Malaita was considerable. The island was divided into nine districts, roughly along the lines of the government administrative districts, and leaders were selected for each district. Courts were set up, each led by a custom chief (''alaha'ohu''), who became powerful figures.Kent, 146. The British initially treated the movement cautiously, even praised aspects of it, but when they found there could be no common ground between the government and the movement, retaliated firmly, with armed police patrols, insisting that the chiefs recant or be arrested. Some did recant, but in September 1947 most were tried in Honiara, charged with terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

or robbery, and convicted to years of hard labour.

However, the movement continued underground, and new leaders renamed the organization the Federal Council. The High Commissioner visited Malaita to negotiate a settlement, and proposed the formation of the Malaita Council, which would have a president elected by members, though they would have to recognize the government's authority and agree to cooperate with their administrators.Kent, 149. The council became the first installment of local government in the Solomon Islands, and its first president was Salana Ga'a. The establishment of the council reduced the tension on Malaita, although Maasina Rule elements did continue until at least 1955. The council was shown not to be simply a means of appeasement, but submitted nearly seventy resolutions and recommendations to the High Commissioner in its first two years of existence.

Post-independence

The Solomon Islands were granted independence in July 1978. The first prime minister was Peter Kenilorea from 'Are'are (Malaita). The provinces were re-organized in 1981, and Malaita became the main island of Malaita Province. Malaita remains the most populous island in the country, and continues to be a source for migrants, a role it played since the days of the labour trade. There are villages of Malaitans in many provinces, including eight "squatter

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

" settlements that make up about 15 percent of the population of Honiara

Honiara () is the capital and largest city of Solomon Islands, situated on the northwestern coast of Guadalcanal. , it had a population of 92,344 people. The city is served by Honiara International Airport and the seaport of Point Cruz, and lie ...

, on Guadalcanal.

Malaitans who had emigrated to Guadalcanal became a focus of the civil war which broke out in 1999, and the Malaita Eagle Force

The Malaita Eagle Force was a militant organisation, originating in the island of Malaita, in the Solomon Islands. It was formed in the early 2000s and soon crossed over to Honiara, the capital of Solomon Islands.

It was set up during 'The Ten ...

(MEF) was formed to protect their interest, both on Guadalcanal and on their home island. The organization of Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) has contributed to the infrastructure development of the island.

After the Solomon Islands switched diplomatic recognition to China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

from Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

in 2019, with a delegation led by prime minister Manasseh Sogavare being received with great hostility and the provincial government refusing to discuss the topics Sogavare had originally arrived to discuss, instead airing concerns over the diplomatic switch. Mass pro-Taiwan protests broke out throughout Malaita, and some protesters even demanded independence from the Solomon Islands, sparking concerns over the fragility of the government.

Geography

Malaita is a thin island, about long and wide at its widest point. Its length is in a north-northwest-to-south-southeast direction, but local custom and official use generally rotate it to straight north-south orientation, and generally refer to the "east coast" or "northern end," when northeast or northwest would be more accurate. To the southwest is theIndispensable Strait

Indispensable Strait is a waterway in the Solomon Islands, running about northwest-southeast from Santa Isabel to Makira (San Cristóbal), between the Florida Islands and Guadalcanal to the southwest, and Malaita to the northeast.

Indispensa ...

, which separates it from Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the seco ...

and the Florida Islands

The Nggela Islands, also known as the Florida Islands, are a small island group in the Central Province of Solomon Islands, a sovereign state (since 1978) in the southwest Pacific Ocean.

The chain is composed of four larger islands and about ...

. To the northeast and east is open Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, except for the small Sikaiana, part of the province northeast. To the northwest of the island is Santa Isabel Island

Santa Isabel Island (also known as Isabel, Ysabel and Mahaga) is the longest in Solomon Islands, the third largest in terms of surface area, and the largest in the group of islands in Isabel Province.

Location and geographic data

Choiseul lies t ...

. To the immediate southwest is South Malaita Island (also called Small Malaita or Maramasike), separated by the narrow Maramasike Passage. Beyond that is Makira, the southernmost large island in the Solomon archipelago.

Malaita's climate is extremely wet. It is located in the

Malaita's climate is extremely wet. It is located in the Intertropical Convergence Zone

The Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ ), known by sailors as the doldrums or the calms because of its monotonous windless weather, is the area where the northeast and the southeast trade winds converge. It encircles Earth near the thermal e ...

("Doldrums"), with its fickle weather patterns. The sun is at zenith over Malaita, and thus the effect is most pronounced, in November and February. Trade winds

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisph ...

come during the Southern Hemisphere's winter, and from about April to August they blow from the southeast fairly steadily. During the summer, fringes of monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscil ...

blow over the island. Because of the surrounding sea, air temperatures are fairly consistent, with a difference between daily highs and lows averaging to . However, across the year, the difference is much less; the mean daily temperature in the warmest month is only warmer than that of the coolest. Rainfall is heavy and there is constant high humidity. The most common daily pattern follows an adiabatic process

In thermodynamics, an adiabatic process (Greek: ''adiábatos'', "impassable") is a type of thermodynamic process that occurs without transferring heat or mass between the thermodynamic system and its environment. Unlike an isothermal process, ...

, with a calm, clear morning, followed by a breeze blowing in from higher pressures over the sea, culminating in a cloudy and drizzly afternoon. At night, the weather pattern reverses, and drizzle and heavy dew dissipate the cloud cover for the morning. Tropical cyclone

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depend ...

s are the only violent weather, but they can be destructive.

Like the other islands in the archipelago, Malaita is near the Andesite line and thus forms part of the Pacific Ring of Fire

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt) is a region around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean where many Types of volcanic eruptions, volcanic eruptions and ...

. Earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

s are common on the island, but there is little evidence of current volcanic activity. The main structural feature of Malaita is the central ridge which runs along the length of the island, with flanking ridges and a few outlying hills. There is a central hilly country, between Auki and the Kwai Harbour Kwai may refer to:

* Kwai (app), a Chinese video sharing app,

* River Kwai (disambiguation), two rivers in Thailand

* Kwai (DC Comics)

* KWAI, radio station,

See also

* Kwaio language

* Kwaio people

Kwaio is an ethnic group found in central Mala ...

, which separates the central ridge into northern and southern halves, the latter being somewhat longer. The northern ridge reaches a height of about , while the southern goes up to . Geologically, Malaita has a basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

ic intrusive core, covered in most places by strata of sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

, especially limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms whe ...

and chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a prec ...

, and littered with fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s. The limestone provides numerous sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are locally also known as ''vrtače'' and shakeholes, and to openi ...

s and cave

A cave or cavern is a natural void in the ground, specifically a space large enough for a human to enter. Caves often form by the weathering of rock and often extend deep underground. The word ''cave'' can refer to smaller openings such as sea ...

rns.

Malaitan hydrology includes thousands of small springs, rivulets, and streams, characteristic of a young drainage pattern. At higher altitudes

Malaitan hydrology includes thousands of small springs, rivulets, and streams, characteristic of a young drainage pattern. At higher altitudes waterfall

A waterfall is a point in a river or stream where water flows over a vertical drop or a series of steep drops. Waterfalls also occur where meltwater drops over the edge of a tabular iceberg or ice shelf.

Waterfalls can be formed in several wa ...

s are common, and in some places canyon

A canyon (from ; archaic British English spelling: ''cañon''), or gorge, is a deep cleft between escarpments or cliffs resulting from weathering and the erosion, erosive activity of a river over geologic time scales. Rivers have a natural tenden ...

s have been cut through the limestone. Nearer the coasts, rivers are slower and deeper, and form mangrove swamps of brackish water, along with alluvial

Alluvium (from Latin ''alluvius'', from ''alluere'' 'to wash against') is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. Alluv ...

deposits of gravel, sand, or mud. The coastal plain is very narrow. Inland soils are of three types, wet black, dry black, and red. The wet black soil, too poorly drained for most horticulture except taro

Taro () (''Colocasia esculenta)'' is a root vegetable. It is the most widely cultivated species of several plants in the family Araceae that are used as vegetables for their corms, leaves, and petioles. Taro corms are a food staple in Africa ...

, is found in valleys or at the foot of slopes. Dry black makes the best gardening sites. The red soil, probably laterite

Laterite is both a soil and a rock type rich in iron and aluminium and is commonly considered to have formed in hot and wet tropical areas. Nearly all laterites are of rusty-red coloration, because of high iron oxide content. They develop by ...

, does not absorb runoff and forms a hard crust, and is preferred for settlement sites.

Environment

There are several vegetation zones based on altitude. Along the coast is either a rocky or sandy beach, wherepandanus

''Pandanus'' is a genus of monocots with some 750 accepted species. They are palm-like, dioecious trees and shrubs native to the Old World tropics and subtropics. The greatest number of species are found in Madagascar and Malaysia. Common names ...

, coconut

The coconut tree (''Cocos nucifera'') is a member of the palm tree family ( Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus ''Cocos''. The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut") can refer to the whole coconut palm, the seed, or the ...

s, and vines predominate, or a swamp, supporting mangrove and sago palms. ''Terminalia

Terminalia may refer to:

* Terminalia (festival), a Roman festival to the god of boundaries Terminus

* ''Terminalia'' (plant), a tree genus

* Terminalia (insect anatomy), the terminal region of the abdomen in insects

* ''Polyscias terminalia'', a ...

'' grows in some drier areas. The lower slopes, up to about , have a hardwood forest of banyans, ''Canarium

''Canarium'' is a genus of about 100 species of tropical and subtropical trees, in the family Burseraceae. They grow naturally across tropical Africa, south and southeast Asia, Indochina, Malesia, Australia and western Pacific Islands; inclu ...

'', Indo-Malayan hardwoods, and, at higher altitudes, bamboo

Bamboos are a diverse group of evergreen perennial flowering plants making up the subfamily Bambusoideae of the grass family Poaceae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. The origin of the word "bamboo" is uncertain, bu ...

. In forested groves, there is relatively little undergrowth. In this zone is also the most intense human cultivation, which, when abandoned, a dense secondary forest

A secondary forest (or second-growth forest) is a forest or woodland area which has re-grown after a timber harvest or clearing for agriculture, until a long enough period has passed so that the effects of the disturbance are no longer evident. ...

grows, which is nearly impassably thick with shrubs and softwoods. Above about is a cloud forest

A cloud forest, also called a water forest, primas forest, or tropical montane cloud forest (TMCF), is a generally tropical or subtropical, evergreen, montane, moist forest characterized by a persistent, frequent or seasonal low-level cloud c ...

, with a dense carpeting of moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta (''sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and hor ...

es, lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.liverworts, with

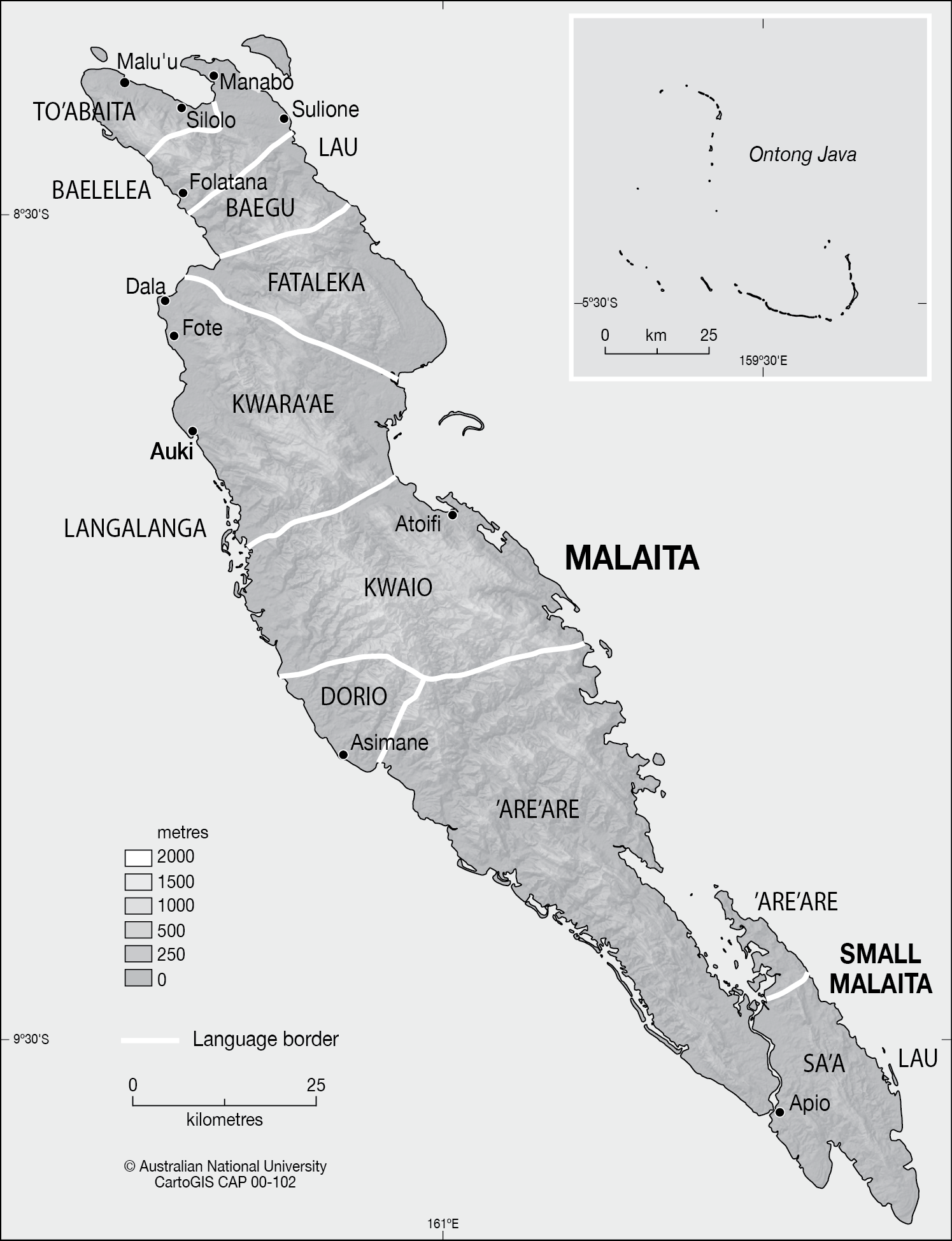

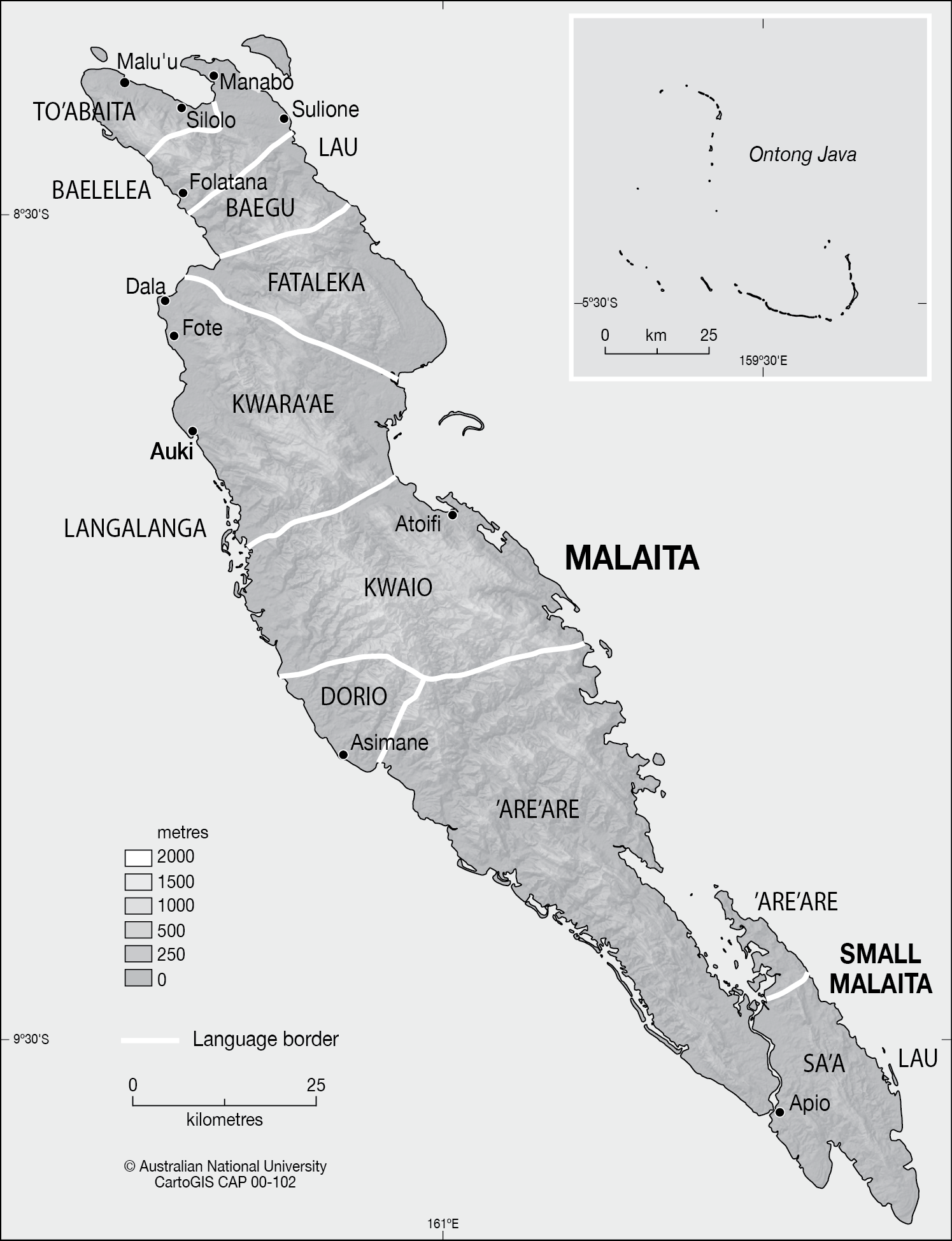

Malaitans speak a variety of languages within the Malaita languages, Malaitan language family, a subbranch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages. The diversity is not as great as once thought, and some of the groups are mutually intelligible. Some of the exaggeration in the number of languages may be due to the inappropriateness of lexicostatistics, lexicostatistical techniques and glottochronology, glottochronological analysis, given the widespread use of word taboo and Metathesis (linguistics), metathesis as word play. According to Harold M. Ross, from north to south along the island's axis, the linguistic groups are roughly the Northern Malaita languages (more properly a collection of dialects without a standard name, generally To'abaita language, To'abaita, Baelelea language, Baelelea, Baeggu language, Baegu, Fataleka language, Fataleka, and Lau language (Malaita), Lau), Kwara'ae language, Kwara'e in the hilly area between the ridges, Kwaio language, Kwaio in about the geographic centre of the island, and 'Are'are language, 'Are'are to the south. Each of these spreads across the width of the island. In addition, there is the Langalanga language, Langalanga in a lagoon on the west coast between the Kwara'ae and Kwaio regions, and Kwarekwareo language, Kwarekwareo on the western coast between the Kwaio and 'Are'are regions, which may be a dialect of Kwaio. Sa'a language, Sa'a, spoken on South Malaita, is also a member of the family. Mutual intelligibility is also aided by the large degree of trade and intermarriage among the groups.

The peoples of Malaita share many aspects of their culture, although they are generally divided into ethnic groups along linguistic lines. In pre-colonial times, settlements were small and moved frequently. Both agnatic descent (patrilineal lines from a founding ancestor) and Cognatic kinship, cognatic descent (through links of outmarrying women) are important. These lineages determine rights of residence and land use in a complex way. In the northern area, local descent groups, united in ritual hierarchies, are largely autonomous, but conceptualize their relationship as a phratry in a manner similar to certain groups in highland New Guinea. In the central area, local descent groups are fully autonomous, though still linked by ritual. In the south, the 'Are'are people developed a more hierarchical organization and more outward orientation, a cultural tradition that reaches its peak on the hereditary chiefs and rituals of Small Malaita to the south. One exception to these generalizations are cultures which have migrated in more recent times, such as the northern Lau people, Lau, who settled in several seaside areas (and offshore islands) in southern Malaita about 200 years ago, and with whom there has been little cultural exchange.

Malaitans speak a variety of languages within the Malaita languages, Malaitan language family, a subbranch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages. The diversity is not as great as once thought, and some of the groups are mutually intelligible. Some of the exaggeration in the number of languages may be due to the inappropriateness of lexicostatistics, lexicostatistical techniques and glottochronology, glottochronological analysis, given the widespread use of word taboo and Metathesis (linguistics), metathesis as word play. According to Harold M. Ross, from north to south along the island's axis, the linguistic groups are roughly the Northern Malaita languages (more properly a collection of dialects without a standard name, generally To'abaita language, To'abaita, Baelelea language, Baelelea, Baeggu language, Baegu, Fataleka language, Fataleka, and Lau language (Malaita), Lau), Kwara'ae language, Kwara'e in the hilly area between the ridges, Kwaio language, Kwaio in about the geographic centre of the island, and 'Are'are language, 'Are'are to the south. Each of these spreads across the width of the island. In addition, there is the Langalanga language, Langalanga in a lagoon on the west coast between the Kwara'ae and Kwaio regions, and Kwarekwareo language, Kwarekwareo on the western coast between the Kwaio and 'Are'are regions, which may be a dialect of Kwaio. Sa'a language, Sa'a, spoken on South Malaita, is also a member of the family. Mutual intelligibility is also aided by the large degree of trade and intermarriage among the groups.

The peoples of Malaita share many aspects of their culture, although they are generally divided into ethnic groups along linguistic lines. In pre-colonial times, settlements were small and moved frequently. Both agnatic descent (patrilineal lines from a founding ancestor) and Cognatic kinship, cognatic descent (through links of outmarrying women) are important. These lineages determine rights of residence and land use in a complex way. In the northern area, local descent groups, united in ritual hierarchies, are largely autonomous, but conceptualize their relationship as a phratry in a manner similar to certain groups in highland New Guinea. In the central area, local descent groups are fully autonomous, though still linked by ritual. In the south, the 'Are'are people developed a more hierarchical organization and more outward orientation, a cultural tradition that reaches its peak on the hereditary chiefs and rituals of Small Malaita to the south. One exception to these generalizations are cultures which have migrated in more recent times, such as the northern Lau people, Lau, who settled in several seaside areas (and offshore islands) in southern Malaita about 200 years ago, and with whom there has been little cultural exchange.

cycad

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody (ligneous) trunk (botany), trunk with a crown (botany), crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants o ...

s as the dominant tall plant.

Like most Pacific islands, there are not large numbers of mammals. Apart from several species of bats, there are introduced species of pigs, cuscuses and rodents. There are also dugongs

The dugong (; ''Dugong dugon'') is a marine mammal. It is one of four living species of the order Sirenia, which also includes three species of manatees. It is the only living representative of the once-diverse family Dugongidae; its closest m ...

in the mangrove swamps, and sometimes dolphin

A dolphin is an aquatic mammal within the infraorder Cetacea. Dolphin species belong to the families Delphinidae (the oceanic dolphins), Platanistidae (the Indian river dolphins), Iniidae (the New World river dolphins), Pontoporiidae (the ...

s in the lagoon.

Reptiles and amphibians are common as well, especially skink

Skinks are lizards belonging to the family Scincidae, a family in the infraorder Scincomorpha. With more than 1,500 described species across 100 different taxonomic genera, the family Scincidae is one of the most diverse families of lizards. Ski ...

s and gecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates throughout the world. They range from .

Geckos ar ...

s. Crocodile

Crocodiles (family (biology), family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to inclu ...

s were once common, but have been so frequently hunted for their hides that they are nearly extinct. There are several venomous sea snakes and two species of venomous land snakes, in the elapid family. There are also numerous species of frog

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely Carnivore, carnivorous group of short-bodied, tailless amphibians composing the order (biology), order Anura (ανοὐρά, literally ''without tail'' in Ancient Greek). The oldest fossil "proto-f ...

s of various sizes.

Fish and aquatic invertebrates are typical of the Indo-Pacific

The Indo-Pacific is a vast biogeographic region of Earth.

In a narrow sense, sometimes known as the Indo-West Pacific or Indo-Pacific Asia, it comprises the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, the western and central Pacific Ocean, and the ...

region. There are a few species of freshwater

Fresh water or freshwater is any naturally occurring liquid or frozen water containing low concentrations of dissolved salts and other total dissolved solids. Although the term specifically excludes seawater and brackish water, it does include ...

fish (including mudskipper

Mudskippers are any of the 23 extant species of amphibious fish from the subfamily Oxudercinae of the goby family Oxudercidae. They are known for their unusual body shapes, preferences for semiaquatic habitats, limited terrestrial locomotion and ...

s and several other species of teleost fish), mangrove crabs and coconut crab

The coconut crab (''Birgus latro'') is a species of terrestrial hermit crab, also known as the robber crab or palm thief. It is the largest terrestrial arthropod in the world, with a weight of up to . It can grow to up to in width from the tip ...

s. On land, centipede

Centipedes (from New Latin , "hundred", and Latin , " foot") are predatory arthropods belonging to the class Chilopoda (Ancient Greek , ''kheilos'', lip, and New Latin suffix , "foot", describing the forcipules) of the subphylum Myriapoda, an ...

s, scorpion

Scorpions are predatory arachnids of the order Scorpiones. They have eight legs, and are easily recognized by a pair of grasping pincers and a narrow, segmented tail, often carried in a characteristic forward curve over the back and always end ...

s, spider

Spiders ( order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight legs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species ...

s, and especially insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

s are very common. All common orders of insects are represented, including some spectacular butterflies. The common Anopheles mosquito ensures that vivax malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, fatigue (medical), tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In se ...

is endemic.

Malaitans once believed in anthropoid apes that lived in the centre of the island, which are said to be tall and come in troops to raid banana plantations.

There are a great number and variety of birds. Almost every family of avifauna were found in Ernst Mayr

Ernst Walter Mayr (; 5 July 1904 – 3 February 2005) was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists. He was also a renowned Taxonomy (biology), taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, Philosophy of biology, philosopher o ...

's 1931 survey. Several species of parrots, cockatoos, and owls are kept as pets. Some bird species are endemic to Malaita.

Important Bird Area

The Malaita Highlands form a site that has been identified byBirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding ...

as an Important Bird Area

An Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) is an area identified using an internationally agreed set of criteria as being globally important for the conservation of bird populations.

IBA was developed and sites are identified by BirdLife Int ...

(IBA) because it supports populations of threatened

Threatened species are any species (including animals, plants and fungi) which are vulnerable to endangerment in the near future. Species that are threatened are sometimes characterised by the population dynamics measure of ''critical depensat ...

or endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

bird species. At 58,379 ha, it encompasses the highest peak of the island and the surrounding montane and lowland forest. Significant birds for which the site was identified include metallic pigeon

The metallic pigeon, (''Columba vitiensis'') also known as white-throated pigeon is a medium-sized, up to 37 cm long, bird in the family Columbidae.

Identification

The adult has an iridescent purple and green crown, black wing and uppertail ...

s, chestnut-bellied imperial pigeon

The chestnut-bellied imperial pigeon (''Ducula brenchleyi'') is a species of bird in the family Columbidae. It is endemic to the southern Solomon Islands.

Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical moist lowland forests and subtropical or ...

s, pale mountain pigeons, duchess lorikeet

The duchess lorikeet (''Charmosynoides margarethae'') is a species of parrot in the family Psittaculidae. It is the only species placed in the genus ''Charmosynoides''. It is found throughout the Solomon Islands archipelago. Its natural habitats ...

s and the endemic red-vested myzomela

The red-vested myzomela (''Myzomela malaitae''), also known as the red-bellied myzomela, is a species of bird in the family Meliphagidae. It is endemic to Malaita (Solomon Islands). Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical moist lowland f ...

s, Malaita fantails and Malaita white-eye

The Malaita white-eye (''Zosterops stresemanni'') is a species of bird in the family Zosteropidae. It is endemic to Malaita in the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller ...

s. Potential threats to the site include logging

Logging is the process of cutting, processing, and moving trees to a location for transport. It may include skidding, on-site processing, and loading of trees or logs onto trucks or skeleton cars.

Logging is the beginning of a supply chain ...

and human population growth

Population growth is the increase in the number of people in a population or dispersed group. Actual global human population growth amounts to around 83 million annually, or 1.1% per year. The global population has grown from 1 billion in 1800 to ...

.

Dolphin hunting

According to Malaitianoral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information about individuals, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews. These interviews are conducted with people wh ...

, a Polynesian woman named Barafaifu introduced dolphin drive hunting from Ontong Java Atoll; she settled in Fanalei village in South Malaita as it was the place for hunting. Dolphin hunting ceased in the mid-19th century, possibly because of the influence of Christian missionaries. However, in 1948 it was revived at settlements on several islands, including Fanalei, Walande (10 km to the north), Ata'a, Felasubua, Sulufou (in the Lau Lagoon) and at Mbita'ama harbour. In most of these communities, the hunt had ceased again by 2004. However, Fanalei in South Malaita remained the preeminent dolphin hunting village.

The dolphins are hunted as food, for their teeth, and for live export. The teeth of certain species have a value for trade, brideprice ceremonial traditions, funeral feasts, and compensation. The teeth of melon-headed whale were traditionally the most desirable; however, they were over-hunted and became locally rare. The other species hunted are spinner dolphin and the pantropical spotted dolphin. While Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphin (''Tursiops aduncus'') have been captured for live export, the bottlenose dolphin is not hunted as the teeth are not considered to have any value.

In recent years only villages on South Malaita Island

South Malaita Island is the island at the southern tip of the larger island of Malaita in the eastern part of the Solomon Islands. It is also known as Small Malaita and Maramasike for Areare speakers and Malamweimwei for more than 80% of the isla ...

have continued to hunt dolphin. In 2010, the villages of Fanalei, Walende, and Bitamae signed a memorandum of agreement with the non-governmental organization, Earth Island Institute, to stop hunting dolphin. However, in early 2013 the agreement broke down and some men in Fanalei resumed hunting. The hunting of dolphin continued in early 2014. Researchers from the South Pacific Whale Research Consortium, the Solomon Islands Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources, and Oregon State University’s Marine Mammal Institute have concluded that hunters from the village of Fanalei in the Solomon Islands have killed more than 1,600 dolphins in 2013, included at least 1,500 pantropical spotted dolphins, 159 spinner dolphins and 15 bottlenose dolphins. The total number killed during the period 1976-2013 was more than 15,400.

The price at which dolphin teeth are traded in Malaita rose from the equivalent of 18c in 2004 to about 90c in 2013.

Demographics and culture

Malaitans are of a varying phenotype. The skin varies from rich chocolate to tawny, most clearly darker than Polynesians, but not generally as dark as the peoples of Bougainville Province, Bougainville or the western Solomons, whom Malaitans refer to as "black men". Most have dark brown or black bushy hair, but it varies in colour from reddish blond, yellow to whitish blond, to ebony black, and in texture from frizzled to merely wavy. Tourists often mistakenly believe the blond hair of Malaitans is bleached by peroxide, but this is not so; the blond or reddish hair colour is quite natural. Male-pattern baldness is widespread, but not as common as among Europeans. Most have smooth skin, but some grow hair on their arms, legs, and chest, and have beards. Most Malaitans are shorter than average Europeans, though not as short as Negritos. Relatively robust physiques are more common among coastal populations, while people from higher altitudes tend to be leaner.Languages and ethnic groups

Malaitans speak a variety of languages within the Malaita languages, Malaitan language family, a subbranch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages. The diversity is not as great as once thought, and some of the groups are mutually intelligible. Some of the exaggeration in the number of languages may be due to the inappropriateness of lexicostatistics, lexicostatistical techniques and glottochronology, glottochronological analysis, given the widespread use of word taboo and Metathesis (linguistics), metathesis as word play. According to Harold M. Ross, from north to south along the island's axis, the linguistic groups are roughly the Northern Malaita languages (more properly a collection of dialects without a standard name, generally To'abaita language, To'abaita, Baelelea language, Baelelea, Baeggu language, Baegu, Fataleka language, Fataleka, and Lau language (Malaita), Lau), Kwara'ae language, Kwara'e in the hilly area between the ridges, Kwaio language, Kwaio in about the geographic centre of the island, and 'Are'are language, 'Are'are to the south. Each of these spreads across the width of the island. In addition, there is the Langalanga language, Langalanga in a lagoon on the west coast between the Kwara'ae and Kwaio regions, and Kwarekwareo language, Kwarekwareo on the western coast between the Kwaio and 'Are'are regions, which may be a dialect of Kwaio. Sa'a language, Sa'a, spoken on South Malaita, is also a member of the family. Mutual intelligibility is also aided by the large degree of trade and intermarriage among the groups.

The peoples of Malaita share many aspects of their culture, although they are generally divided into ethnic groups along linguistic lines. In pre-colonial times, settlements were small and moved frequently. Both agnatic descent (patrilineal lines from a founding ancestor) and Cognatic kinship, cognatic descent (through links of outmarrying women) are important. These lineages determine rights of residence and land use in a complex way. In the northern area, local descent groups, united in ritual hierarchies, are largely autonomous, but conceptualize their relationship as a phratry in a manner similar to certain groups in highland New Guinea. In the central area, local descent groups are fully autonomous, though still linked by ritual. In the south, the 'Are'are people developed a more hierarchical organization and more outward orientation, a cultural tradition that reaches its peak on the hereditary chiefs and rituals of Small Malaita to the south. One exception to these generalizations are cultures which have migrated in more recent times, such as the northern Lau people, Lau, who settled in several seaside areas (and offshore islands) in southern Malaita about 200 years ago, and with whom there has been little cultural exchange.

Malaitans speak a variety of languages within the Malaita languages, Malaitan language family, a subbranch of the Malayo-Polynesian languages. The diversity is not as great as once thought, and some of the groups are mutually intelligible. Some of the exaggeration in the number of languages may be due to the inappropriateness of lexicostatistics, lexicostatistical techniques and glottochronology, glottochronological analysis, given the widespread use of word taboo and Metathesis (linguistics), metathesis as word play. According to Harold M. Ross, from north to south along the island's axis, the linguistic groups are roughly the Northern Malaita languages (more properly a collection of dialects without a standard name, generally To'abaita language, To'abaita, Baelelea language, Baelelea, Baeggu language, Baegu, Fataleka language, Fataleka, and Lau language (Malaita), Lau), Kwara'ae language, Kwara'e in the hilly area between the ridges, Kwaio language, Kwaio in about the geographic centre of the island, and 'Are'are language, 'Are'are to the south. Each of these spreads across the width of the island. In addition, there is the Langalanga language, Langalanga in a lagoon on the west coast between the Kwara'ae and Kwaio regions, and Kwarekwareo language, Kwarekwareo on the western coast between the Kwaio and 'Are'are regions, which may be a dialect of Kwaio. Sa'a language, Sa'a, spoken on South Malaita, is also a member of the family. Mutual intelligibility is also aided by the large degree of trade and intermarriage among the groups.

The peoples of Malaita share many aspects of their culture, although they are generally divided into ethnic groups along linguistic lines. In pre-colonial times, settlements were small and moved frequently. Both agnatic descent (patrilineal lines from a founding ancestor) and Cognatic kinship, cognatic descent (through links of outmarrying women) are important. These lineages determine rights of residence and land use in a complex way. In the northern area, local descent groups, united in ritual hierarchies, are largely autonomous, but conceptualize their relationship as a phratry in a manner similar to certain groups in highland New Guinea. In the central area, local descent groups are fully autonomous, though still linked by ritual. In the south, the 'Are'are people developed a more hierarchical organization and more outward orientation, a cultural tradition that reaches its peak on the hereditary chiefs and rituals of Small Malaita to the south. One exception to these generalizations are cultures which have migrated in more recent times, such as the northern Lau people, Lau, who settled in several seaside areas (and offshore islands) in southern Malaita about 200 years ago, and with whom there has been little cultural exchange.

Religion

The traditional religion of the island is ancestor worship. In one oral tradition, the earliest residents knew the name of the creator, but thought his name was so holy that they did not want to tell their children. Instead, they instructed their children to address their requests to their ancestors, who would be their mediators.Leslie Fugui and Simeon Butu, "Religion," in ''Ples Blong Iumi'', 76. In some parts of Malaita the high god responsible for creation, who has now retired from active work, is known as ''Agalimae'' ("the god of the universe"). Congregations of local descent groups propitiate their ancestors at shrines, led by ritual officiants (''fataabu'' in northern Malaita). On Malaita, many shrines have been preserved, not only for their sanctity but also because they serve as territorial markers that can resolve land disputes. With European contact, Roman Catholic Church, Catholics and Church of England, Anglicans spread their gospels, and many missionaries were killed. The Protestant South Seas Evangelical Mission (SSEM, now known as the South Seas Evangelical Church, SSEC), originally based inQueensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

, made considerable inroads by following the imported workers home to their native islands. More recently, Jehovah's Witnesses and the Seventh-day Adventist Church have converted many. Many Malaitans have been active in the Solomon Islands Christian Association, a national inter-denominational organization that set a precedent for cooperation during the period of independence. The Kwaio people, Kwaio people have been the most resistant to Christianity.

Economy

For the most part, the Malaitans survive by subsistence agriculture, withtaro

Taro () (''Colocasia esculenta)'' is a root vegetable. It is the most widely cultivated species of several plants in the family Araceae that are used as vegetables for their corms, leaves, and petioles. Taro corms are a food staple in Africa ...

and sweet potatoes as the most important crops. After the establishment of government control, a plantation was established on the west coast, near Baunani. However, many Malaitans work on plantations on other islands in the archipelago, for most the only way to buy prestigious Western goods. Retail trade was largely conducted by Chinese merchants, with headquarters in Honiara

Honiara () is the capital and largest city of Solomon Islands, situated on the northwestern coast of Guadalcanal. , it had a population of 92,344 people. The city is served by Honiara International Airport and the seaport of Point Cruz, and lie ...

, and dispatching goods to remote locations on the island, where they are sometimes purchased by middlemen who keep "stores" (usually of suitcase side) in remote places.

Arts

The Malaitans are famous for their music and dance, which are sometimes associated with rituals. Several of the groups, including the 'Are'are, famous for their panpipe ensembles, are among SSEC members whose traditional music is no longer performed for religious reasons.Zemp, Hugo. Liner notes to ''Solomon Islands: 'Are'are Panpipe Ensembles.'' Le Chant du Monde LDX 274961.62, 1994. Page 58-59. Secular dancing is similar to widespread patterns in the Solomons, following patterns learned from plantation labour gangs or moves learned at the cinema in Honiara. Sacred dances follow strict formal patterns, and incorporate panpipers in the group. Some dances represent traditional activities, such as the ''tue tue'' dance, about fishing, which depict movements of the boat and fish, and the birds overhead. Malaitan shell-money, manufactured in the Langalanga lagoon, is the traditional currency, and was used throughout the Solomon Islands, as far as Bougainville Province, Bougainville. The money consists of small polished shell disks which are drilled and placed on strings. It can be used as payment for brideprice, funeral feasts and compensation, as well ordinary purposes as a cash equivalent. It is also worn as an adornment and status symbol. The standard unit, known as the ''tafuliae'', is several strands 1.5 m in length. Previously the money was also manufactured on Makira andGuadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the seco ...

.Romano Kokonge, 63. It is still produced on Malaita, but much is inherited, from father to son, and the old traditional strings are now rare.Kent, 44. Porpoise teeth are also used as money, often woven into belts.

Notes

References

* Roger Keesing, ''Kwaio Religion: The Living and the Dead in a Solomon Island Society''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982. * Roger M. Keesing and Peter Corris. ''Lightning Meets the West Wind: The Malaita Massacre''. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 1980. * Janet Kent. ''The Solomon Islands''. Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1972. * James Page (Australian educationist), James Page, 'Education and Acculturation on Malaita: An Ethnography of Intraethnic and Interethnic Affinities'.''The Journal of Intercultural Studies.'' 1988. #15/16:74-81; available on-line at http://eprints.qut.edu.au/archive/00003566/. * ''Ples Blong Iumi: Solomon Islands: The Past Four Thousand Years''. Honiara: University of the South Pacific, 1989. * Harold M. Ross. ''Baegu: Social and Ecological Organization in Malaita, Solomon Islands''. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1973.Further reading

*Guppy, Henry B. (1887) ''The Solomon Islands and Their Natives''. London: Swan Sonnenschein, Lowrey & Co {{authority control Islands of the Solomon Islands Important Bird Areas of the Solomon Islands