Mahavrata on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

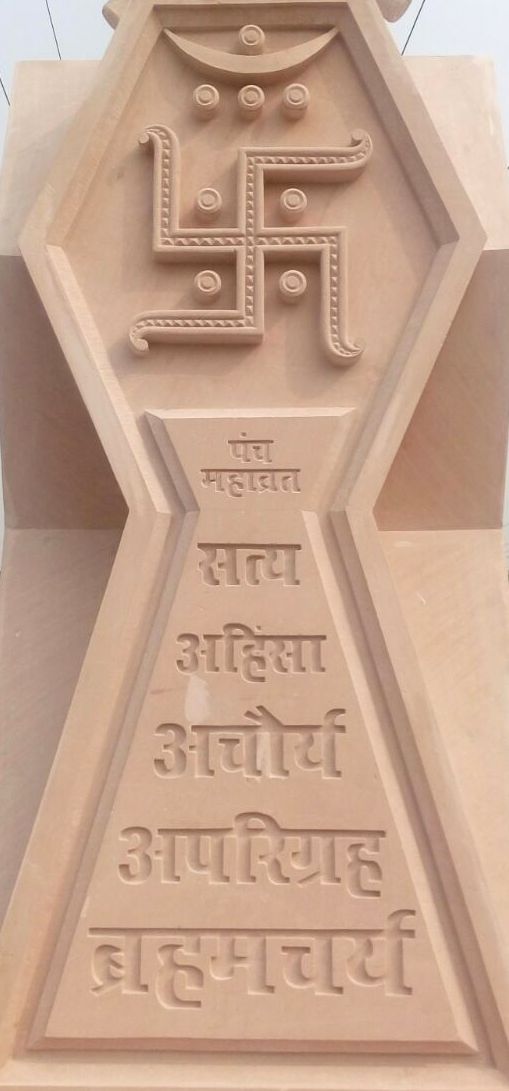

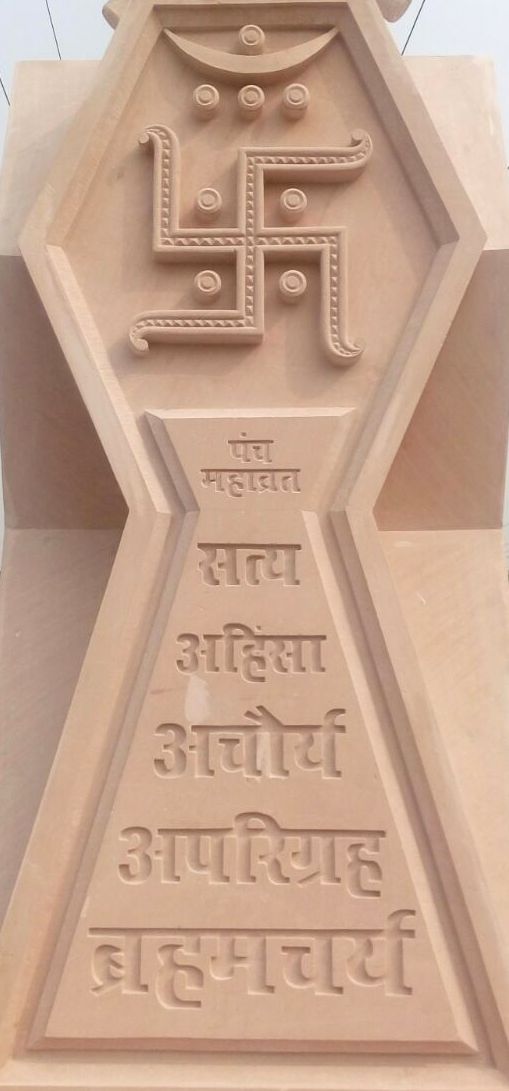

The Five Vows of

The Five Vows of

''Mahavrata'' (lit. major vows) are the five fundamental observed by the Jain ascetics. Also known as the "Five Vows", they are described in detail in the ''

''Mahavrata'' (lit. major vows) are the five fundamental observed by the Jain ascetics. Also known as the "Five Vows", they are described in detail in the ''

Five Great Vows (Maha-vratas) of Jainism

, Jainism Literature Center, Harvard University

Nor shall I myself kill living beings (nor cause others to do it, nor consent to it).

As long as I live, I confess and blame, repent and exempt myself of these sins, in the thrice threefold way,i.e. acting, commanding, consenting, either in the past or the present or the future. in mind, speech, and body. ##A Nirgrantha is careful in his walk, not careless.This could also be translated: he who is careful in his walk is a Nirgrantha, not he who is careless.

The Kevalin assigns as the reason, that a Nirgrantha, careless in his walk, might (with his feet) hurt or displace or injure or kill living beings.

Hence a Nirgrantha is careful in his walk, not careless in his walk. ##A Nirgrantha searches into his mind (i.e. thoughts and intentions). If his mind is sinful, blamable, intent on works, acting on impulses,''Aṇhayakare'' explained by ''karmāsravakāri''. produces cutting and splitting (or division and dissension), quarrels, faults, and pains, injures living beings, or kills creatures, he should not employ such a mind in action. But if, on the contrary, it is not sinful, etc., then he may put it in action. ##A Nirgrantha searches into his speech; if his speech is sinful, blamable, intent on works, acting on impulses, produces cutting and splitting (or division and dissension), quarrels, faults, and pains, injures living beings, or kills creatures, he should not utter that speech. But if, on the contrary, it is not sinful, etc., then he may utter it. ##A Nirgrantha is careful in laying down his utensils of begging, he is not careless in it.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is careless in laying down his utensils of begging, might hurt or displace or injure or kill all sorts of living beings.

Hence a Nirgrantha is careful in laying down his utensils of begging, he is not careless in it. ##A Nirgrantha eats and drinks after inspecting his food and drink; he does not eat and drink without inspecting his food and drink.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha would eat and drink without inspecting his food and drink, he might hurt and displace or injure or kill all sorts of living beings.

Hence a Nirgrantha eats and drinks after inspecting his food and drink, not without doing so. #I renounce all vices of lying speech (arising) from anger or greed or fear or mirth.

I shall neither myself speak lies, nor cause others to speak lies, nor consent to the speaking of lies by others.

I confess and blame, repent and exempt myself of these sins in the thrice threefold way, in mind, speech, and body. ##A Nirgrantha speaks after deliberation, not without deliberation.

The Kevalin says: Without deliberation a Nirgrantha might utter a falsehood in his speech. ##A Nirgrantha comprehends (and renounces) anger, he is not angry.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is moved by anger, and is angry, might utter a falsehood in his speech. ##A Nirgrantha comprehends (and renounces) greed, he is not greedy.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is moved by greed, and is greedy, might utter a falsehood in his speech. ##A Nirgrantha comprehends (and renounces) fear, he is not afraid.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is moved by fear, and is afraid, might utter a falsehood in his speech. ##A Nirgrantha comprehends (and renounces) mirth, he is not mirthful.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is moved by mirth, and is mirthful, might utter a falsehood in his speech. #I renounce all taking of anything not given, either in a village or a town or a wood, either of little or much, of small or great, of living or lifeless things.

I shall neither take myself what is not given, nor cause others to take it, nor consent to their taking it.

As long as I live, I confess and blame, repent and exempt myself of these sins, in the thrice threefold way, in mind, speech, and body. ##A Nirgrantha begs after deliberation, for a limited ground, not without deliberation.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha begs without deliberation for a limited ground, he might take what is not given. ##A Nirgrantha consumes his food and drink with permission (of his superior), not without his permission.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha consumes his food and drink without the superior’s permission, he might eat what is not given. ##A Nirgrantha who has taken possession of some ground, should always take possession of a limited part of it and for a fixed time.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha who has taken possession of some ground, should take possession of an unlimited part of it and for an unfixed time, he might take what is not given. ##A Nirgrantha who has taken possession of some ground, should constantly have his grant renewed.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha has not constantly his grant renewed, he might take possession of what is not given. ##A Nirgrantha begs for a limited ground for his co-religionists after deliberation, not without deliberation.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha should beg without deliberation, he might take possession of what is not given. #I renounce all sexual pleasures, either with gods or men or animals.

I shall not give way to sensuality, etc. ... and exempt myself. ##A Nirgrantha does not continually discuss topics relating to women.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha discusses such topics, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. ##A Nirgrantha does not regard and contemplate the lovely forms of women.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha regards and contemplates the lovely forms of women, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. ##A Nirgrantha does not recall to his mind the pleasures and amusements he formerly had with women.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha recalls to his mind the pleasures and amusements he formerly had with women, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. ##A Nirgrantha does not eat and drink too much, nor does he drink liquors or eat highly-seasoned dishes.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha did eat and drink too much, or did drink liquors and eat highly-seasoned dishes, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. ##A Nirgrantha does not occupy a bed or couch affectedThis may mean belonging to, or close by. by women, animals, or eunuchs.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha did occupy a bed or couch affected by women, animals, or eunuchs, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. #I renounce all attachments,This means the pleasure in external objects. whether little or much, small or great, living or lifeless;

neither shall I myself form such attachments, nor cause others to do so, nor consent to their doing so, etc. ... and exempt myself. ##If a creature with ears hears agreeable and disagreeable sounds, it should not be attached to, nor delighted with, nor desiring of, nor infatuated by, nor covetous of, nor disturbed by the agreeable or disagreeable sounds.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant sounds, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to hear sounds, which reach the ear, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ##If a creature with eyes sees agreeable and disagreeable forms (or colours), it should not be attached, etc., to them.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant forms, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to see forms, which reach the eye, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ##If a creature with an organ of smell smells agreeable or disagreeable smells, it should not be attached, etc., to them.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant smells, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to smell the smells, which reach the nose, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ##If a creature with a tongue tastes agreeable or disagreeable tastes, it should not be attached, etc., to them.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant tastes, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to taste the tastes, which reach the tongue, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ##If a creature with an organ of feeling feels agreeable or disagreeable touches, it should not be attached, etc., to them.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant touches, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to feel the touches, which reach the organ of feeling, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ::He who is well provided with these great vows and their 25 clauses is really Houseless, if he, according to the sacred lore, the precepts, and the way correctly practises, follows, executes, explains, establishes, and, according to the precept, effects them.

The Five Vows of

The Five Vows of Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion whose three main pillars are nonviolence (), asceticism (), and a rejection of all simplistic and one-sided views of truth and reality (). Jainism traces its s ...

include the ''mahāvratas'' (major vows) and ''aṇuvratas'' (minor vows).

Overview

Jain ethical code prescribes two '' dharmas'' or rules of conduct. One for those who wish to becomeascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

and another for the ''śrāvaka

Śrāvaka (Sanskrit) or Sāvaka (Pali) means "hearer" or, more generally, "disciple". This term is used in Buddhism and Jainism. In Jainism, a śrāvaka is any lay Jain so the term śrāvaka has been used for the Jain community itself (for exampl ...

'' (householders). Five fundamental vows are prescribed for both votaries. These vows are observed by '' śrāvakas'' (householders) partially and are termed as ''anuvratas'' (small vows). Ascetics observe these fives vows more strictly and therefore observe complete abstinence. These five vows are:

* ''Ahiṃsā

(, IAST: , ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to actions towards all living beings. It is a key virtue in Indian religions like Jainism, Buddhism and Hinduism.

(also spelled Ahinsa) is one of the cardinal vi ...

'' (Non-violence)

* ''Satya

(Sanskrit: ; IAST: ) is a Sanskrit word that can be translated as "truth" or "essence.“ In Indian religions, it refers to a kind of virtue found across them. This virtue most commonly refers to being truthful in one's thoughts, speech and act ...

'' (Truth)

* '' Asteya'' (Non-stealing)

* ''Brahmacharya

''Brahmacharya'' (; Sanskrit: Devanagari: ब्रह्मचर्य) is the concept within Indian religions that literally means "conduct consistent with Brahman" or "on the path of Brahman". Brahmacharya, a discipline of controlling ...

'' (Chastity)

* ''Aparigraha

Non-possession (, ) is a religious tenet followed in Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain traditions in South Asia. In Jainism, is the virtue of non-possessiveness, non-grasping, or non-greediness.

is the opposite of . It means keeping the desire for po ...

'' (Non-possession)

According to the Jain text '' Puruşārthasiddhyupāya'':

Apart from five main vows, a householder is expected to observe seven supplementary vows (''śeelas'') and last '' sallekhanā'' vow.

''Mahāvratas'' (major vows)

''Mahavrata'' (lit. major vows) are the five fundamental observed by the Jain ascetics. Also known as the "Five Vows", they are described in detail in the ''

''Mahavrata'' (lit. major vows) are the five fundamental observed by the Jain ascetics. Also known as the "Five Vows", they are described in detail in the ''Tattvartha Sutra

''Tattvārthasūtra'', meaning "On the Nature 'artha''of Reality 'tattva'' (also known as ''Tattvarth-adhigama-sutra'' or ''Moksha-shastra'') is an ancient Jain text written by ''Acharya (Jainism), Acharya'' Umaswami in Sanskrit betwee ...

'' (Chapter 7) and the '' Acaranga Sutra'' (Book 2, Lecture 15). According to Acharya Samantabhadra’s Ratnakaraņdaka śrāvakācāra:

Ahiṃsā

Ahimsa (non-injury) is formalised into Jain doctrine as the first and foremost vow. According to the Jain text, ''Tattvarthsutra'': "The severance of vitalities out of passion is injury."Satya

Satya is the vow to not lie, and to speak the truth. A monk or nun must not speak the false, and either be silent or speak the truth. According to Pravin Shah, the great vow of satya applies to "speech, mind, and deed", and it also means discouraging and disapproving others who perpetuate a falsehood. The underlying cause of falsehood is passion and therefore, it is said to cause ''hiṃsā'' (injury).Asteya

Asteya as a great vow means not take anything which is not freely given and without permission. It applies to anything even if unattended or unclaimed, whether it is of worth or worthless thing. This vow of non-stealing applies to action, speech and thought. Further a mendicant, states Shah, must neither encourage others to do so nor approve of such activities. According to the Jain text, ''Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya

''Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya'' is a major Jain text authored by Amritchandra. Acharya Amritchandra was a Digambara monk who lived in the tenth century ( Vikram Samvat). ''Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya'' deals with the conduct of householder (''ś ...

'':

According to '' Tattvarthasutra'', five observances that strengthen this vow are:

*Residence in a solitary place

*Residence in a deserted habitation

*Causing no hindrance to others,

*Acceptance of clean food, and

*Not quarreling with brother monks.

Brahmacharya

Brahmacharya as a great vow of Jain mendicants means celibacy and avoiding any form of sexual activity with body, words or mind. A monk or nun should not enjoy sensual pleasures, which includes all the five senses, nor ask others to do the same, nor approve of another monk or nun engaging in sexual or sensual activity.Pravin K ShahFive Great Vows (Maha-vratas) of Jainism

, Jainism Literature Center, Harvard University

Aparigraha

According to ''Tattvarthsutra'', "Infatuation is attachment to possessions". Jain texts mentions that "attachment to possessions (''parigraha'') is of two kinds: attachment to internal possessions (''ābhyantara parigraha''), and attachment to external possessions (''bāhya parigraha''). The fourteen internal possessions are: *Wrong belief *The three sex-passions **Male sex-passion **Female sex-passion **Neuter sex-passion *Six defects **Laughter **Liking **Disliking **Sorrow **Fear **Disgust *Four passions **Anger **Pride **Deceitfulness **Greed External possessions are divided into two subclasses, the non-living, and the living. According to Jain texts, both internal and external possessions are proved to be ''hiṃsā'' (injury).25 clauses from the ''Ācārāṅga Sūtra''

In Book 2, Lecture 15 of the '' Ācārāṅga Sūtra'', 5 clauses are given for each of the 5 vows, giving a total of 25 clauses. The following isHermann Jacobi

Hermann Georg Jacobi (11 February 1850 – 19 October 1937) was an eminent German Indologist.

Education

Jacobi was born in Köln (Cologne) on 11 February 1850. He was educated in the gymnasium of Cologne and then went to the University of Be ...

's 1884 English translation of the 25 clauses.

#I renounce all killing of living beings, whether subtile or gross, whether movable or immovable. Nor shall I myself kill living beings (nor cause others to do it, nor consent to it).

As long as I live, I confess and blame, repent and exempt myself of these sins, in the thrice threefold way,i.e. acting, commanding, consenting, either in the past or the present or the future. in mind, speech, and body. ##A Nirgrantha is careful in his walk, not careless.This could also be translated: he who is careful in his walk is a Nirgrantha, not he who is careless.

The Kevalin assigns as the reason, that a Nirgrantha, careless in his walk, might (with his feet) hurt or displace or injure or kill living beings.

Hence a Nirgrantha is careful in his walk, not careless in his walk. ##A Nirgrantha searches into his mind (i.e. thoughts and intentions). If his mind is sinful, blamable, intent on works, acting on impulses,''Aṇhayakare'' explained by ''karmāsravakāri''. produces cutting and splitting (or division and dissension), quarrels, faults, and pains, injures living beings, or kills creatures, he should not employ such a mind in action. But if, on the contrary, it is not sinful, etc., then he may put it in action. ##A Nirgrantha searches into his speech; if his speech is sinful, blamable, intent on works, acting on impulses, produces cutting and splitting (or division and dissension), quarrels, faults, and pains, injures living beings, or kills creatures, he should not utter that speech. But if, on the contrary, it is not sinful, etc., then he may utter it. ##A Nirgrantha is careful in laying down his utensils of begging, he is not careless in it.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is careless in laying down his utensils of begging, might hurt or displace or injure or kill all sorts of living beings.

Hence a Nirgrantha is careful in laying down his utensils of begging, he is not careless in it. ##A Nirgrantha eats and drinks after inspecting his food and drink; he does not eat and drink without inspecting his food and drink.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha would eat and drink without inspecting his food and drink, he might hurt and displace or injure or kill all sorts of living beings.

Hence a Nirgrantha eats and drinks after inspecting his food and drink, not without doing so. #I renounce all vices of lying speech (arising) from anger or greed or fear or mirth.

I shall neither myself speak lies, nor cause others to speak lies, nor consent to the speaking of lies by others.

I confess and blame, repent and exempt myself of these sins in the thrice threefold way, in mind, speech, and body. ##A Nirgrantha speaks after deliberation, not without deliberation.

The Kevalin says: Without deliberation a Nirgrantha might utter a falsehood in his speech. ##A Nirgrantha comprehends (and renounces) anger, he is not angry.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is moved by anger, and is angry, might utter a falsehood in his speech. ##A Nirgrantha comprehends (and renounces) greed, he is not greedy.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is moved by greed, and is greedy, might utter a falsehood in his speech. ##A Nirgrantha comprehends (and renounces) fear, he is not afraid.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is moved by fear, and is afraid, might utter a falsehood in his speech. ##A Nirgrantha comprehends (and renounces) mirth, he is not mirthful.

The Kevalin says: A Nirgrantha who is moved by mirth, and is mirthful, might utter a falsehood in his speech. #I renounce all taking of anything not given, either in a village or a town or a wood, either of little or much, of small or great, of living or lifeless things.

I shall neither take myself what is not given, nor cause others to take it, nor consent to their taking it.

As long as I live, I confess and blame, repent and exempt myself of these sins, in the thrice threefold way, in mind, speech, and body. ##A Nirgrantha begs after deliberation, for a limited ground, not without deliberation.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha begs without deliberation for a limited ground, he might take what is not given. ##A Nirgrantha consumes his food and drink with permission (of his superior), not without his permission.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha consumes his food and drink without the superior’s permission, he might eat what is not given. ##A Nirgrantha who has taken possession of some ground, should always take possession of a limited part of it and for a fixed time.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha who has taken possession of some ground, should take possession of an unlimited part of it and for an unfixed time, he might take what is not given. ##A Nirgrantha who has taken possession of some ground, should constantly have his grant renewed.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha has not constantly his grant renewed, he might take possession of what is not given. ##A Nirgrantha begs for a limited ground for his co-religionists after deliberation, not without deliberation.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha should beg without deliberation, he might take possession of what is not given. #I renounce all sexual pleasures, either with gods or men or animals.

I shall not give way to sensuality, etc. ... and exempt myself. ##A Nirgrantha does not continually discuss topics relating to women.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha discusses such topics, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. ##A Nirgrantha does not regard and contemplate the lovely forms of women.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha regards and contemplates the lovely forms of women, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. ##A Nirgrantha does not recall to his mind the pleasures and amusements he formerly had with women.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha recalls to his mind the pleasures and amusements he formerly had with women, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. ##A Nirgrantha does not eat and drink too much, nor does he drink liquors or eat highly-seasoned dishes.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha did eat and drink too much, or did drink liquors and eat highly-seasoned dishes, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. ##A Nirgrantha does not occupy a bed or couch affectedThis may mean belonging to, or close by. by women, animals, or eunuchs.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha did occupy a bed or couch affected by women, animals, or eunuchs, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace. #I renounce all attachments,This means the pleasure in external objects. whether little or much, small or great, living or lifeless;

neither shall I myself form such attachments, nor cause others to do so, nor consent to their doing so, etc. ... and exempt myself. ##If a creature with ears hears agreeable and disagreeable sounds, it should not be attached to, nor delighted with, nor desiring of, nor infatuated by, nor covetous of, nor disturbed by the agreeable or disagreeable sounds.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant sounds, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to hear sounds, which reach the ear, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ##If a creature with eyes sees agreeable and disagreeable forms (or colours), it should not be attached, etc., to them.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant forms, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to see forms, which reach the eye, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ##If a creature with an organ of smell smells agreeable or disagreeable smells, it should not be attached, etc., to them.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant smells, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to smell the smells, which reach the nose, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ##If a creature with a tongue tastes agreeable or disagreeable tastes, it should not be attached, etc., to them.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant tastes, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to taste the tastes, which reach the tongue, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ##If a creature with an organ of feeling feels agreeable or disagreeable touches, it should not be attached, etc., to them.

The Kevalin says: If a Nirgrantha is thus affected by the pleasant or unpleasant touches, he might fall from the law declared by the Kevalin, because of the destruction or disturbance of his peace.

If it is impossible not to feel the touches, which reach the organ of feeling, the mendicant should avoid love or hate, originated by them. ::He who is well provided with these great vows and their 25 clauses is really Houseless, if he, according to the sacred lore, the precepts, and the way correctly practises, follows, executes, explains, establishes, and, according to the precept, effects them.

''Aṇuvratas'' (minor vows)

The five great vows apply only to ascetics in Jainism, and in their place are five minor vows for laypeople (householders). The historic texts of Jains accept that any activity by a layperson would involve some form of ''himsa'' (violence) to some living beings, and therefore the minor vow emphasizes reduction of the impact and active efforts to protect. The five "minor vows" in Jainism are modeled after the great vows, but differ in degree and they are less demanding or restrictive than the same "great vows" for ascetics. Thus, ''brahmacharya'' for householders means chastity, or being sexually faithful to one's partner. Similarly, states John Cort, a mendicant's great vow of ahimsa requires that he or she must avoid gross and subtle forms of violence to all six kinds of living beings (earth beings, water beings, fire beings, wind beings, vegetable beings and mobile beings). In contrast, a Jain householder's minor vow requires no gross violence against higher life forms and an effort to protect animals from "slaughter, beating, injury and suffering". Apart from five fundamental vows seven supplementary vows are prescribed for a ''śrāvaka''. These include three ''guņa vratas'' (Merit vows) and four ''śikşā vratas'' (Disciplinary vows). The vow of ''sallekhanâ'' is observed by the votary at the end of his life. It is prescribed both for the ascetics and householders. According to the Jain text, Puruşārthasiddhyupāya: The five 'lesser vows' of anuvrata consist of the five greater vows but with less restrictions to incorporate the duties of a householder, i.e. a layperson with a home, he or she has responsibilities to the family, community and society that a Jain monk does not have. These minor vows have the following incorporated into ethical conduct: # Take account of the responsibilities of a householder. # Are often limited in time. # Are often limited in scope.Guņa vratas

#''Digvrata'' - restriction on movement with regard to directions. #''Bhogopabhogaparimana'' - vow of limiting consumable and non-consumable things #''Anartha-daṇḍaviramana'' - refraining from harmful occupations and activities (purposeless sins).Śikşā vratas

#''Sāmāyika

''Sāmāyika'' is the vow of periodic concentration observed by the Jains. It is one of the essential duties prescribed for both the ''Śrāvaka'' (householders) and ascetics. The preposition ''sam'' means one state of being. To become one is ...

'' - vow to meditate and concentrate periodically.

#''Deśāvrata'' - limiting movement to certain places for a fixed period of time.

#''Poṣadhopavāsa'' - fasting at regular intervals.

#''Atihti samvibhag'' (or ''Dānavrata'') - Vow of offering food to the ascetic and needy people.

Sallekhanā

An ascetic or householder who has observed all the prescribed vows to shed the ''karmas

Karma (, from , ; ) is an ancient Indian concept that refers to an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptively called ...

'', takes the vow of ''sallekhanā'' at the end of his life. According to the Jain text, ''Purushartha Siddhyupaya'', "sallekhana enable a householder to carry with him his wealth of piety".

Transgressions

There are five, five transgressions respectively for the vows and the supplementary vows.See also

*Jain philosophy

Jain philosophy or Jaina philosophy refers to the Ancient India, ancient Indian Indian philosophy, philosophical system of the Jainism, Jain religion. It comprises all the Philosophy, philosophical investigations and systems of inquiry that dev ...

* Five precepts

* Five precepts (Taoism)

* Pratima (Jainism)

In Jainism, ''Pratima'' () is a step or a stage marking the spiritual rise of a lay person (''shravak''). There are eleven such steps called ''pratima''. After passing the eleven steps, one is no longer a ''sravaka'', but a ''muni'' (monk).

Rule ...

* Tapas (Indian religions)

Tapas (Sanskrit: तपस्, romanized: tapas) is a variety of austere spiritual meditation practices in Indian religions. In Jainism, it means asceticism (austerities, body mortification); in Buddhism, it denotes spiritual practices includin ...

* Tapas (Jain religion)

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * *External links

* {{Jainism topics Jain law Codes of conduct