Madoc on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd (also spelled Madog) was, according to

Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd (also spelled Madog) was, according to

Madoc's purported father,

Madoc's purported father,

On 26 November 1608, Peter Wynne, a member of Captain

On 26 November 1608, Peter Wynne, a member of Captain  Folk tradition has long claimed that a site called " Devil's Backbone" at Rose Island, about fourteen miles upstream from

Folk tradition has long claimed that a site called " Devil's Backbone" at Rose Island, about fourteen miles upstream from

A plaque at

A plaque at

Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd (also spelled Madog) was, according to

Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd (also spelled Madog) was, according to folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

, a Welsh prince who sailed to America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

in 1170, over three hundred years before Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

's voyage in 1492.

According to the story, he was a son of Owain Gwynedd

Owain ap Gruffudd ( 23 or 28 November 1170) was King of Gwynedd, North Wales, from 1137 until his death in 1170, succeeding his father Gruffudd ap Cynan. He was called Owain the Great ( cy, Owain Fawr) and the first to be ...

, and took to the sea to flee internecine violence at home. The "Madoc story" legend evidently evolved out of a medieval tradition about a Welsh hero's sea voyage, to which only allusions survive. However, it attained its greatest prominence during the Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

, when English and Welsh writers wrote of the claim that Madoc had come to the Americas as an assertion of prior discovery, and hence legal possession, of North America by the Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

.

The Madoc story remained popular in later centuries, and a later development asserted that Madoc's voyagers had intermarried with local Native Americans, and that their Welsh-speaking descendants still live somewhere in the United States. These "Welsh Indians" were credited with the construction of a number of landmarks throughout the Midwestern United States

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. I ...

, and a number of white travelers were inspired to go look for them. The Madoc story has been the subject of much speculation in the context of possible pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

Pre-Columbian transoceanic contact theories are speculative theories which propose that possible visits to the Americas, possible interactions with the indigenous peoples of the Americas, or both, were made by people from Africa, Asia, Europe, ...

. No conclusive archaeological proof of such a man or his voyages has been found in the New or Old World; however, speculation abounds connecting him with certain sites, such as Devil's Backbone, located on the Ohio River at Fourteen Mile Creek near Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

.

Story

Madoc's purported father,

Madoc's purported father, Owain Gwynedd

Owain ap Gruffudd ( 23 or 28 November 1170) was King of Gwynedd, North Wales, from 1137 until his death in 1170, succeeding his father Gruffudd ap Cynan. He was called Owain the Great ( cy, Owain Fawr) and the first to be ...

, was a real king of Gwynedd

Prior to the Conquest of Wales by Edward I, Conquest of Wales, completed in 1282, Wales consisted of a number of independent monarchy, kingdoms, the most important being Kingdom of Gwynedd, Gwynedd, Kingdom of Powys, Powys, Deheubarth (originally ...

during the 12th century and is widely considered one of the greatest Welsh rulers of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. His reign was fraught with battles with other Welsh princes and with Henry II of England

Henry II (5 March 1133 – 6 July 1189), also known as Henry Curtmantle (french: link=no, Court-manteau), Henry FitzEmpress, or Henry Plantagenet, was King of England from 1154 until his death in 1189, and as such, was the first Angevin king ...

. At his death in 1170, a bloody dispute broke out between his heir, Hywel Hywel (), sometimes anglicised as Howel or Howell, is a Welsh masculine given name. It may refer to:

* Saint Hywel, a sixth-century disciple of Saint Teilo and the king of Brittany in the Arthurian legend.

*Hywel ap Rhodri Molwynog, 9th-century ki ...

the Poet-Prince, and Owain's younger sons, Maelgwn, Rhodri Rhodri is a male first name of Welsh origin. It is derived from the elements ''rhod'' "wheel" and ''rhi'' "king".

It may refer to the following people:

*Rhodri Molwynog ap Idwal (690–754), Welsh king of Gwynedd (720—754)

* Rhodri Mawr ap ...

, and led by Dafydd Dafydd is a Welsh masculine given name, related to David, and more rarely a surname. People so named include:

Given name Medieval era

:''Ordered chronologically''

* Dafydd ab Owain Gwynedd (c. 1145-1203), Prince of Gwynedd

* Dafydd ap Gruffydd (123 ...

, two the children of the Princess-Dowager Cristen ferch Gronwy and one the child of Gwladus ferch Llywarch. Owain had at least 13 children from his two wives and several more children born out of wedlock but legally acknowledged under Welsh tradition. According to the legend, Madoc and his brother (Rhirid or Rhiryd) were among them, though no contemporary record attests to this.

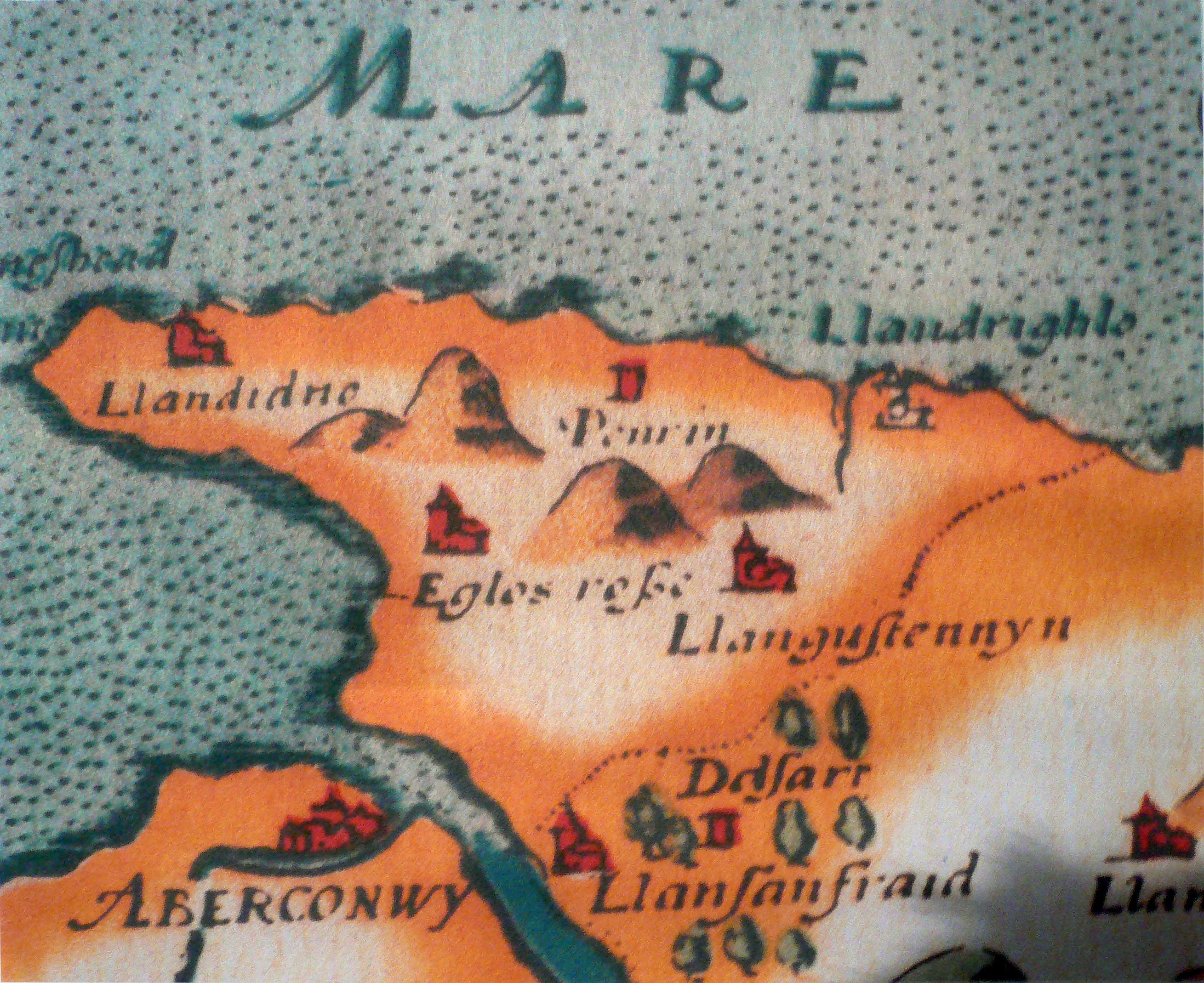

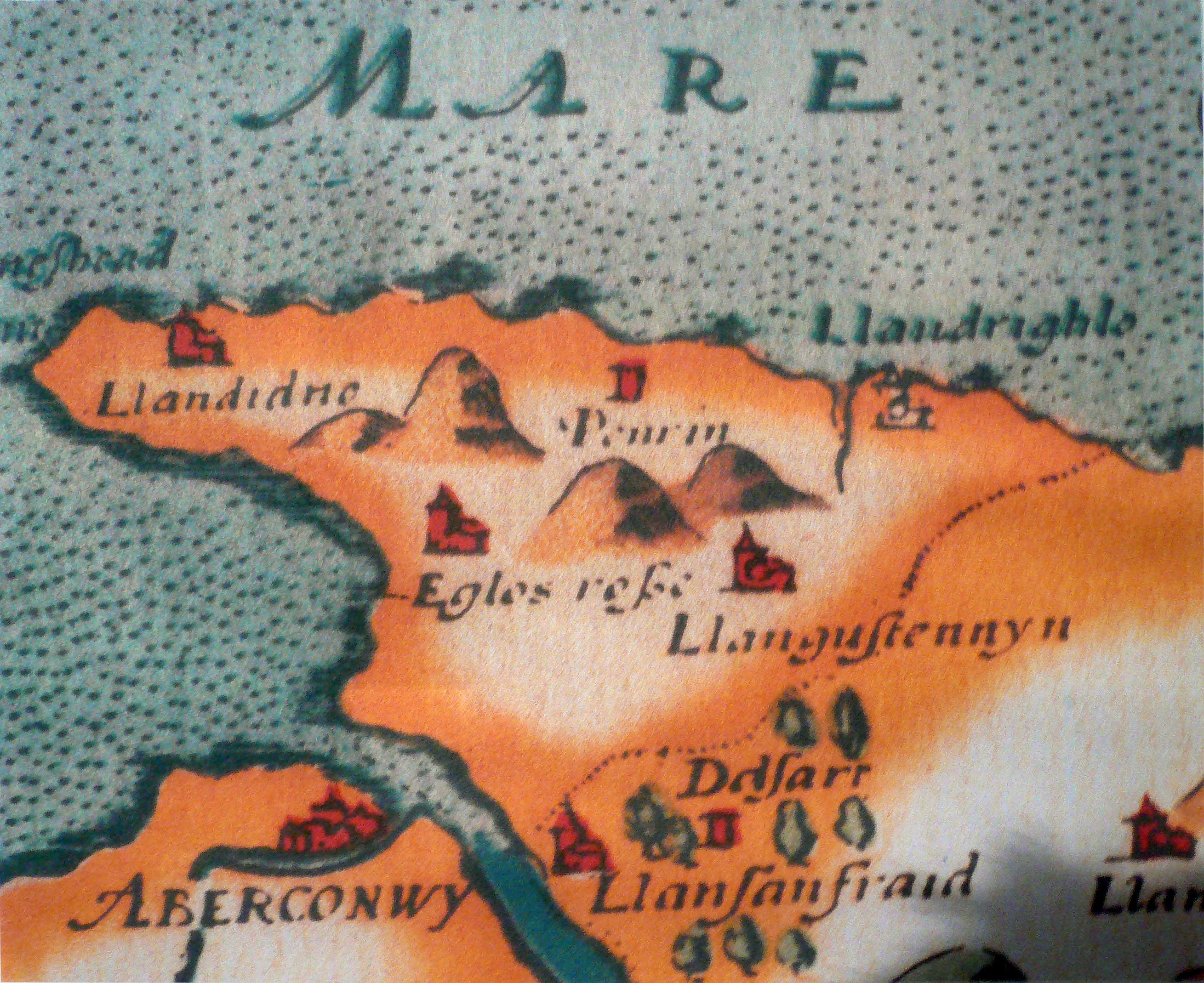

The 1584 ''Historie of Cambria'' by David Powel

David Powel (1549/52 – 1598) was a Welsh Church of England clergyman and historian who published the first printed history of Wales in 1584.

Life

Powel was born in Denbighshire and commenced his studies at the University of Oxford when he was 1 ...

says that Madoc was disheartened by this family fighting, and that he and Rhirid set sail from Llandrillo (Rhos-on-Sea

Rhos-on-Sea ( cy, Llandrillo-yn-Rhos) is a seaside resort and community in Conwy County Borough, Wales. The population was 7,593 at the 2011 census. It adjoins Colwyn Bay and is named after the Welsh kingdom of Rhos established there in late ...

) in the cantref

A cantref ( ; ; plural cantrefi or cantrefs; also rendered as ''cantred'') was a medieval Welsh land division, particularly important in the administration of Welsh law.

Description

Land in medieval Wales was divided into ''cantrefi'', which were ...

of Rhos to explore the western ocean. They purportedly discovered a distant and abundant land in 1170 where about one hundred men, women and children disembarked to form a colony. According to Humphrey Llwyd

Humphrey Llwyd (also spelled Lhuyd) (1527–1568) was a Welsh cartographer, author, antiquary and Member of Parliament. He was a leading member of the Renaissance period in Wales along with other such men as Thomas Salisbury and William ...

's 1559 ''Cronica Walliae

'' Cronica Walliae '' (full title: ''Cronica Walliae a Rege Cadwalader ad annum 1294'') is a manuscript of chronological history by Humphrey Llwyd written in 1559. Llwyd translated versions of a medieval text about Wales' history, ''Brut y Tywys ...

'' and in many other copied sources, Madoc and some others returned to Wales to recruit additional settlers. After gathering eleven ships and 120 men, women and children, the Prince and his recruiters sailed west a second time to "that Westerne countrie" and ported in "Mexico", a fact that too was cited by Reuben T. Durrett in his work ''Traditions of the earliest visits of foreigners to north America'', and stated he was never to return to Wales again.

Madoc's landing place has also been suggested to be "Mobile, Alabama; Florida; Newfoundland; Newport, Rhode Island; Yarmouth, Nova Scotia; Virginia; points in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean including the mouth of the Mississippi River; the Yucatan; the isthmus of Tehuantepec, Panama; the Caribbean coast of South America; various islands in the West Indies and the Bahamas along with Bermuda; and the mouth of the Amazon River". Although the folklore tradition acknowledges that no witness ever returned from the second colonial expedition to report this, the story continues that Madoc's colonists travelled up the vast river systems of North America, raising structures and encountering friendly and unfriendly tribes of Native Americans before finally settling down somewhere in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

or the Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

. They are reported to be the founders of various civilisations such as the Aztec

The Aztecs () were a Mesoamerican culture that flourished in central Mexico in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those g ...

, the Maya

Maya may refer to:

Civilizations

* Maya peoples, of southern Mexico and northern Central America

** Maya civilization, the historical civilization of the Maya peoples

** Maya language, the languages of the Maya peoples

* Maya (Ethiopia), a populat ...

and the Inca

The Inca Empire (also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire), called ''Tawantinsuyu'' by its subjects, (Quechua for the "Realm of the Four Parts", "four parts together" ) was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America. The admin ...

.

Sources

The Madoc story evidently originated in medieval romance. There are allusions to what may have been a sea voyage tale akin to '' The Voyage of Saint Brendan'', but no detailed version of it survives. The earliest certain reference to a seafaring Madoc or Madog appears in a ''cywydd

The cywydd (; plural ) is one of the most important metrical forms in traditional Welsh poetry (cerdd dafod).

There are a variety of forms of the cywydd, but the word on its own is generally used to refer to the ("long-lined couplet") as it is b ...

'' by the Welsh poet Maredudd ap Rhys

Maredudd ap Rhys ( fl. 1450–1485), also spelt Meredudd ap Rhys, was a Welsh language poet and priest from Powys. He was born in gentry, having pedigree blood, as discovered from the Peniarth Manuscripts. He is thought to have been the bardic tu ...

(fl. 1450–1483) of Powys

Powys (; ) is a Local government in Wales#Principal areas, county and Preserved counties of Wales, preserved county in Wales. It is named after the Kingdom of Powys which was a Welsh succession of states, successor state, petty kingdom and princi ...

, which mentions a Madog who is a son or descendant of Owain Gwynedd and who voyaged to the sea. The poem is addressed to a local squire, thanking him for a fishing net on a patron's behalf. Madog is referred to as "Splendid Madog ... / Of Owain Gwynedd's line, / He desired not land ... / Or worldy wealth but the sea."

A Flemish writer called Willem, in around 1250 to 1255, identifies himself in his poem '' Van den Vos Reinaerde'' as "Willem die Madoc maecte Willem die Madocke maecte (c. 1200 – c. 1250; "William-who-made-the-Madoc") is the traditional designation of the author of '' Van den vos Reynaerde'', a Middle Dutch version of the story of ''Reynard the Fox''.

Name of the author

The name of the ...

" (Willem, the author of Madoc, known as "Willem the Minstrel"). Though no copies of "Madoc" survive, Gwyn Williams tells us that "In the seventeenth century a fragment of a reputed copy of the work is said to have been found in Poitiers". It provides no topographical details relating to North America, but mentions a sea that may be the Sargasso Sea

The Sargasso Sea () is a region of the Atlantic Ocean bounded by four currents forming an ocean gyre. Unlike all other regions called seas, it has no land boundaries. It is distinguished from other parts of the Atlantic Ocean by its charac ...

and says that Madoc (not related to Owain in the fragment according to Gwyn Williams) discovered an island paradise, where he intended "to launch a new kingdom of love and music". There are also claims that the Welsh poet and genealogist Gutun Owain

Gutun Owain ( fl. 1456–1497) was a poet in the Welsh language. He was born near Oswestry in what is now north Shropshire and was a student of Dafydd ab Edmwnd.

Gutun Owain was closely associated with the Cistercian abbey of Valle Crucis where ...

wrote about Madoc before 1492. Gwyn Williams in ''Madoc, the Making of a Myth'', makes it clear that Madoc is not mentioned in any of Owain's surviving manuscripts.

The Madoc legend attained its greatest prominence during the Elizabethan era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

, when Welsh and English writers used it to bolster British claims in the New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 3 ...

versus those of Spain. The earliest surviving full account of Madoc's voyage, the first to make the claim that Madoc had come to America before Columbus, appears in Humphrey Llwyd's ''Cronica Walliae

'' Cronica Walliae '' (full title: ''Cronica Walliae a Rege Cadwalader ad annum 1294'') is a manuscript of chronological history by Humphrey Llwyd written in 1559. Llwyd translated versions of a medieval text about Wales' history, ''Brut y Tywys ...

'' (published in 1559), an English adaptation of the ''Brut y Tywysogion

''Brut y Tywysogion'' ( en, Chronicle of the Princes) is one of the most important primary sources for Welsh history. It is an annalistic chronicle that serves as a continuation of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s ''Historia Regum Britanniae''. ''Bru ...

''.

John Dee

John Dee (13 July 1527 – 1608 or 1609) was an English mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, teacher, occultist, and alchemist. He was the court astronomer for, and advisor to, Elizabeth I, and spent much of his time on alchemy, divinatio ...

used Llwyd's manuscript when he submitted the treatise "Title Royal" to Queen Elizabeth in 1580, which stated that "The Lord Madoc, sonne to Owen Gwynned, Prince of Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

, led a Colonie and inhabited in Terra Florida or thereabouts" in 1170. The story was first published by George Peckham's as ''A True Report of the late Discoveries of the Newfound Landes'' (1583), and like Dee it was used to support English claims to the Americas. It was picked up in David Powel

David Powel (1549/52 – 1598) was a Welsh Church of England clergyman and historian who published the first printed history of Wales in 1584.

Life

Powel was born in Denbighshire and commenced his studies at the University of Oxford when he was 1 ...

's ''Historie of Cambria'' (1584), and Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt (; 1553 – 23 November 1616) was an English writer. He is known for promoting the English colonization of North America through his works, notably ''Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America'' (1582) and ''The Pri ...

's ''The Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation'' (1589). Dee went so far as to assert that Brutus of Troy

Brutus, also called Brute of Troy, is a legendary descendant of the Trojan hero Aeneas, known in medieval British history as the eponymous founder and first king of Britain. This legend first appears in the ''Historia Brittonum'', an anonymous ...

and King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

as well as Madoc had conquered lands in the Americas and therefore their heir Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

had a priority claim there.

Thomas Herbert popularised the stories told by Dee and Powel, adding more detail from sources unknown, suggesting that Madoc may have landed in Canada, Florida, or even Mexico, and reporting that Mexican sources stated that they used currach

A currach ( ) is a type of Irish boat with a wooden frame, over which animal skins or hides were once stretched, though now canvas is more usual. It is sometimes anglicised as "curragh".

The construction and design of the currach are unique ...

s.

The "Welsh Indians" were not claimed until later. Morgan Jones's tract is the first account, and was printed by ''The Gentleman's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term ''magazine'' (from the French ''magazine'' ...

'', launching a slew of publications on the subject. There is no genetic or archaeological evidence that the Mandan

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still res ...

are related to the Welsh, however, and John Evans and Lewis and Clark reported they had found no Welsh Indians. The Mandan are still alive today; the tribe was decimated by a smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

epidemic in 1837–1838 and banded with the nearby Hidatsa

The Hidatsa are a Siouan people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Their language is related to that of the Crow, and they are sometimes considered a parent t ...

and Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

into the ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

Three Affiliated Tribes

The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation (MHA Nation), also known as the Three Affiliated Tribes ( Mandan: ''Miiti Naamni''; Hidatsa: ''Awadi Aguraawi''; Arikara: ''ačitaanu' táWIt''), is a Native American Nation resulting from the alliance of ...

.

The Welsh Indian legend was revived in the 1840s and 1850s; this time the Zunis

The Zuni ( zun, A:shiwi; formerly spelled ''Zuñi'') are Native American Pueblo peoples native to the Zuni River valley. The Zuni are a Federally recognized tribe and most live in the Pueblo of Zuni on the Zuni River, a tributary of the Lit ...

, Hopi

The Hopi are a Native American ethnic group who primarily live on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona, United States. As of the 2010 census, there are 19,338 Hopi in the country. The Hopi Tribe is a sovereign nation within the Unite ...

s, and Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest federally recognized tribe in the United ...

were claimed to be of Welsh descent by George Ruxton

George Frederick Ruxton (24 July 1821 – 29 August 1848) was a British explorer and travel writer. He was a lieutenant in the British Army, received a medal for gallantry from Queen Isabella II of Spain, was a hunter and explorer and published p ...

(Hopis, 1846), P. G. S. Ten Broeck (Zunis, 1854), and Abbé Emmanuel Domenach (Zunis, 1860), among others. Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

became interested in the supposed Hopi-Welsh connection: in 1858 Young sent a Welshman with Jacob Hamblin

Jacob Hamblin (April 2, 1819 – August 31, 1886) was a Western pioneer, a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and a diplomat to various Native American tribes of the Southwest and Great Basin. He a ...

to the Hopi mesas to check for Welsh-speakers there. None was found, but in 1863 Hamblin brought three Hopi men to Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

, where they were "besieged by Welshmen wanting them to utter Celtic words", to no avail.

Llewellyn Harris, a Welsh-American Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

missionary who visited the Zuni in 1878, wrote that they had many Welsh words in their language, and that they claimed their descent from the "Cambaraga"—white men who had come by sea 300 years before the Spanish. However, Harris's claims have never been independently verified.

Welsh Indians

On 26 November 1608, Peter Wynne, a member of Captain

On 26 November 1608, Peter Wynne, a member of Captain Christopher Newport

Christopher Newport (1561–1617) was an English seaman and privateer. He is best known as the captain of the ''Susan Constant'', the largest of three ships which carried settlers for the Virginia Company in 1607 on the way to found the settle ...

's exploration party to the villages of the Monacan people

The Monacan Indian Nation is one of eleven Native American tribes recognized since the late 20th century by the U.S. state of Virginia. In January 2018, the United States Congress passed an act to provide federal recognition as tribes to the Mo ...

, Virginia Siouan speakers above the falls of the James River

The James River is a river in the U.S. state of Virginia that begins in the Appalachian Mountains and flows U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed April 1, 2011 to Chesapea ...

in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, wrote a letter to John Egerton, informing him that some members of Newport's party believed the pronunciation of the Monacans' language resembled "Welch", which Wynne spoke, and asked Wynne to act as interpreter. The Monacan were among those non-Algonquian tribes collectively referred to by the Algonquians as "Mandoag".

Another early settler to claim an encounter with a Welsh-speaking Indian was the Reverend Morgan Jones, who told Thomas Lloyd, William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

's deputy, that he had been captured in 1669 in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

by members of a tribe identified as the Doeg, who were said to be a part of the Tuscarora Tuscarora may refer to the following:

First nations and Native American people and culture

* Tuscarora people

**''Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation'' (1960)

* Tuscarora language, an Iroquoian language of the Tuscarora people

* ...

. (However, there is no evidence that the Doeg proper were part of the Tuscarora.) According to Jones, the chief spared his life when he heard Jones speak Welsh, a tongue he understood. Jones' report says that he then lived with the Doeg for several months preaching the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

in Welsh and then returned to the British Colonies

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

where he recorded his adventure in 1686. The historian Gwyn A. Williams

Gwyn Alfred "Alf" Williams (30 September 1925 – 16 November 1995) was a Welsh historian particularly known for his work on Antonio Gramsci and Francisco Goya as well as on Welsh history.

Life

Williams was born in the iron town of Dowla ...

comments, "This is a complete farrago and may have been intended as a hoax".

Folk tradition has long claimed that a site called " Devil's Backbone" at Rose Island, about fourteen miles upstream from

Folk tradition has long claimed that a site called " Devil's Backbone" at Rose Island, about fourteen miles upstream from Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

, was once home to a colony of Welsh-speaking Indians. The eighteenth-century Missouri River explorer John Evans of Waunfawr

Waunfawr (''gwaun'' + ''mawr'', en, large moorland/meadow) is a village and community, SE of Caernarfon, near the Snowdonia National Park, Gwynedd, in Wales.

Description

Waunfawr is in the Gwyrfai valley, on the A4085 road from Caernarfon to ...

in Wales took up his journey in part to find the Welsh-descended "Padoucas" or "Madogwys" tribes.

In northwest Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, legends of the Welsh have become part of the myth surrounding the unknown origin of a mysterious rock formation on Fort Mountain. Historian, Gwyn A. Williams, author of ''Madoc: The Making of a Myth'', suggests that Cherokee tradition concerning that ruin may have been influenced by contemporary European-American legends of the " Welsh Indians". A newspaper writer in Georgia, Walter Putnam, mentioned the Madoc legend in 2008. The story of Welsh explorers is one of several legends surrounding that site.

In northeastern Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, there is a theory that the "Welsh Caves" in DeSoto State Park

DeSoto State Park is a public recreation area located on Lookout Mountain northeast of Fort Payne, Alabama. The state park covers of forest, rivers, waterfalls, and mountain terrain. It borders the Little River, which flows into the nearby Lit ...

were built by Madoc's party, since local native tribes were not known to have ever practised such stonework or excavation as was found on the site.

In 1810, John Sevier

John Sevier (September 23, 1745 September 24, 1815) was an American soldier, frontiersman, and politician, and one of the founding fathers of the State of Tennessee. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, he played a leading role in Tennes ...

, the first governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of Tennessee, wrote to his friend Major Amos Stoddard

Amos Stoddard (October 26, 1762 – May 11, 1813) was a career United States Army officer who served in both the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, in which he was mortally wounded.

In 1804, Stoddard was the Commandant of the militar ...

about a conversation he had in 1782 with the old Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

chief Oconostota

Oconostota (c. 1710–1783) was a Cherokee ''skiagusta'' (war chief) of Chota, which was for nearly four decades the primary town in the Overhill territory, and within what is now Monroe County, Tennessee. He served as the First Beloved Man of Ch ...

concerning ancient fortifications built along the Alabama River

The Alabama River, in the U.S. state of Alabama, is formed by the Tallapoosa and Coosa rivers, which unite about north of Montgomery, near the town of Wetumpka.

The river flows west to Selma, then southwest until, about from Mobile, it un ...

. The chief allegedly told him that the forts were built by a white people called "Welsh", as protection against the ancestors of the Cherokee, who eventually drove them from the region. Sevier had also written in 1799 of the alleged discovery of six skeletons in brass armour bearing the Welsh coat-of-arms. He claims that Madoc and the Welsh were first in Alabama.

In 1824, Thomas S. Hinde wrote a letter to John S. Williams, editor of The American Pioneer, regarding the Madoc Tradition. In the letter, Hinde claimed to have gathered testimony from numerous sources that stated Welsh people under Owen Ap Zuinch had come to America in the twelfth century, over three hundred years before Christopher Columbus. Hinde claimed that in 1799, six soldiers had been dug up near Jeffersonville, Indiana

Jeffersonville is a city and the county seat of Clark County, Indiana, Clark County, Indiana, United States, situated along the Ohio River. Locally, the city is often referred to by the abbreviated name Jeff. It lies directly across the Ohio River ...

, on the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

with breastplate

A breastplate or chestplate is a device worn over the torso to protect it from injury, as an item of religious significance, or as an item of status. A breastplate is sometimes worn by mythological beings as a distinctive item of clothing. It is ...

s that contained Welsh coats-of-arms.

Encounters with Welsh Indians

Thomas Jefferson had heard of Welsh-speaking Indian tribes. In a letter written toMeriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 – October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with ...

by Jefferson on 22 January 1804, he speaks of searching for the Welsh Indians "said to be up the Missouri". The historian Stephen E. Ambrose writes in his history book ''Undaunted Courage

''Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West'' (), written by Stephen Ambrose, is a 1996 biography of Meriwether Lewis of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The book is based on journals and letters ...

'' that Thomas Jefferson believed the "Madoc story" to be true and instructed the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

to find the descendants of the Madoc Welsh Indians.

Mandans

In all, at least thirteen real tribes, five unidentified tribes, and three unnamed tribes have been suggested as "Welsh Indians". Eventually, the legend settled on identifying the Welsh Indians with theMandan

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still res ...

people, who were said to differ from their neighbours in culture, language, and appearance. The painter George Catlin

George Catlin (July 26, 1796 – December 23, 1872) was an American adventurer, lawyer, painter, author, and traveler, who specialized in portraits of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans in the Old West.

Traveling to the We ...

suggested the Mandans were descendants of Madoc and his fellow voyagers in ''North American Indians'' (1841); he found the round Mandan Bull Boat similar to the Welsh coracle

A coracle is a small, rounded, lightweight boat of the sort traditionally used in Wales, and also in parts of the West Country and in Ireland, particularly the River Boyne, and in Scotland, particularly the River Spey. The word is also used of s ...

, and he thought the advanced architecture of Mandan villages must have been learned from Europeans (advanced North American societies such as the Mississippian and Hopewell tradition

The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from 1 ...

s were not well known in Catlin's time). Supporters of this claim have drawn links between Madoc and the Mandan mythological figure "Lone Man", who, according to one tale, protected some villagers from a flooding river with a wooden corral.

Later writings

Several attempts to confirm Madoc's historicity have been made, but historians of early America, notablySamuel Eliot Morison

Samuel Eliot Morison (July 9, 1887 – May 15, 1976) was an American historian noted for his works of maritime history and American history that were both authoritative and popular. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1912, and ta ...

, regard the story as a myth. Madoc's legend has been a notable subject for poets, however. The most famous account in English is Robert Southey

Robert Southey ( or ; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey began as a ra ...

's long 1805 poem ''Madoc

Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd (also spelled Madog) was, according to folklore, a Welsh prince who sailed to America in 1170, over three hundred years before Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492.

According to the story, he was a son of Owain Gwyned ...

'', which uses the story to explore the poet's freethinking and egalitarian ideals.

Southey wrote ''Madoc'' to help finance a trip of his own to America, where he and Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poe ...

hoped to establish a Utopian state they called a "Pantisocracy

Pantisocracy (from the Greek πᾶν and ἰσοκρατία meaning "equal or level government by/for all") was a utopian scheme devised in 1794 by, among others, the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Robert Southey for an egalitarian community. ...

". Southey's poem in turn inspired the twentieth-century poet Paul Muldoon

Paul Muldoon (born 20 June 1951) is an Irish poet. He has published more than thirty collections and won a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the T. S. Eliot Prize. At Princeton University he is currently both the Howard G. B. Clark '21 University Pr ...

to write ''Madoc: A Mystery'', which won the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize

The Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize is a British literary prize established in 1963 in tribute to Geoffrey Faber, founder and first Chairman of the publisher Faber & Faber. It recognises a single volume of poetry or fiction by a United Kingdom, Irish ...

in 1992. It explores what may have happened if Southey and Coleridge had succeeded in coming to America to found their "ideal state". In Russian, the noted poet Alexander S. Pushkin composed a short poem "Madoc in Wales" (Медок в Уаллах, 1829) on the topic.

John Smith, historian of Virginia, wrote in 1624 of the ''Chronicles of Wales'' reports Madoc went to the New World in 1170 A.D. (over 300 years before Columbus) with some men and women. Smith says the ''Chronicles'' say Madoc then went back to Wales to get more people and made a second trip back to the New World.

Legacy

The township of Madoc, Ontario, and the nearby village ofMadoc

Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd (also spelled Madog) was, according to folklore, a Welsh prince who sailed to America in 1170, over three hundred years before Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492.

According to the story, he was a son of Owain Gwyned ...

are both named in the prince's memory, as are several local guest houses and pubs throughout North America and the United Kingdom. The Welsh town of Porthmadog

Porthmadog (; ), originally Portmadoc until 1974 and locally as "Port", is a Welsh coastal town and community in the Eifionydd area of Gwynedd and the historic county of Caernarfonshire. It lies east of Criccieth, south-west of Blaenau Ffest ...

(meaning "Madoc's Port" in English) and the village of Tremadog

Tremadog (formerly Tremadoc) is a village in the community of Porthmadog, in Gwynedd, north west Wales; about north of Porthmadog town-centre. It was a planned settlement, founded by William Madocks, who bought the land in 1798. The centre of ...

("Madoc's Town") in the county of Gwynedd

Gwynedd (; ) is a county and preserved county (latter with differing boundaries; includes the Isle of Anglesey) in the north-west of Wales. It shares borders with Powys, Conwy County Borough, Denbighshire, Anglesey over the Menai Strait, and C ...

are actually named after the industrialist and Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

William Alexander Madocks

William Alexander Madocks (17 June 1773 – 15 September 1828) was a British politician and landowner who served as Member of Parliament (MP) for the borough of Boston in Lincolnshire from 1802 to 1820, and then for Chippenham in Wiltshire fro ...

, their principal developer, and additionally influenced by the legendary son of Owain Gwynedd, Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd.

The ''Prince Madog

Madoc ab Owain Gwynedd (also spelled Madog) was, according to folklore, a Welsh prince who sailed to America in 1170, over three hundred years before Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492.

According to the story, he was a son of Owain Gwyne ...

'', a research vessel owned by the University of Wales

The University of Wales (Welsh language, Welsh: ''Prifysgol Cymru'') is a confederal university based in Cardiff, Wales. Founded by royal charter in 1893 as a federal university with three constituent colleges – Aberystwyth, Bangor and Cardiff � ...

and P&O Maritime, entered service in 2001, replacing an earlier research vessel of the same name that first entered service in 1968.

Fort Mountain State Park

Fort Mountain State Park is a Georgia state park located between Chatsworth and Ellijay on Fort Mountain. The state park was founded in 1938 and is named for an ancient rock wall located on the peak.The plaque has been changed, leaving no reference to Madoc or the Welsh.

In 1953, the

Daughters of the American Revolution

The Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) is a lineage-based membership service organization for women who are directly descended from a person involved in the United States' efforts towards independence.

A non-profit group, they promote ...

erected a plaque at Fort Morgan Fort Morgan can apply to any one of several places in the United States:

*Fort Morgan (Alabama), a fort at the mouth of Mobile Bay

*Fort Morgan, Alabama, a nearby community

*Fort Morgan (Colorado), a frontier military post located in present-day Fo ...

on the shores of Mobile Bay, Alabama

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. The ...

, reading:

The plaque was removed by the Alabama Parks Service in 2008 and put in storage. Since then there has been much controversy over efforts to get the plaque reinstalled.

In literature

Fiction

* * * * * * * * * *Poetry

* *Juvenile

*Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * *Franklin, Caroline (2003): "The Welsh American Dream:Iolo Morganwg

Edward Williams, better known by his bardic name Iolo Morganwg (; 10 March 1747 – 18 December 1826), was a Welsh antiquarian, poet and collector.Jones, Mary (2004)"Edward Williams/Iolo Morganwg/Iolo Morgannwg" From ''Jones' Celtic Encyclopedi ...

, Robert Southey and the Madoc legend." In ''English romanticism and the Celtic world'', ed. by Gerard Carruthers and Alan Rawes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 69–84.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

*External links

* * * {{authority control American folklore Medieval legends Legendary Welsh people Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact Welsh explorers Welsh royalty Origin myths Welsh people of Irish descent