Macellum Of Pozzuoli on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Macellum of Pozzuoli ( it, Macellum di Pozzuoli) was the

The Macellum of Pozzuoli ( it, Macellum di Pozzuoli) was the

King

King

Between 1806 and 1818 further excavations exposed the whole of the "Serapeum" or "Temple of Serapis". The excavations lost

Between 1806 and 1818 further excavations exposed the whole of the "Serapeum" or "Temple of Serapis". The excavations lost

The Macellum of Pozzuoli ( it, Macellum di Pozzuoli) was the

The Macellum of Pozzuoli ( it, Macellum di Pozzuoli) was the macellum

A macellum (plural: ''macella''; ''makellon'') is an ancient Roman indoor market building that sold mostly provisions (especially meat and fish). The building normally sat alongside the forum and basilica, providing a place in which a market coul ...

or market building of the Roman colony

A Roman (plural ) was originally a Roman outpost established in conquered territory to secure it. Eventually, however, the term came to denote the highest status of a Roman city. It is also the origin of the modern term ''colony''.

Characteri ...

of Puteoli, now the city of Pozzuoli

Pozzuoli (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Italian region of Campania. It is the main city of the Phlegrean Peninsula.

History

Pozzuoli began as the Greek colony of ''Dicaearchia'' ( el, öö¿ö¤öÝö ...

in southern Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. When first excavated in the 18th century, the discovery of a statue of Serapis

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian deity. The cult of Serapis was promoted during the third century BC on the orders of Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt as a means to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his r ...

led to the building being misidentified as the city's serapeum

A serapeum is a temple or other religious institution dedicated to the syncretic Greco-Egyptian deity Serapis, who combined aspects of Osiris and Apis in a humanized form that was accepted by the Ptolemaic Greeks of Alexandria. There were seve ...

or Temple of Serapis.

A band of borings or ''Gastrochaenolites

''Gastrochaenolites'' is a trace fossil formed as a clavate (club-shaped) boring in a hard substrate such as a shell, rock or carbonate hardground. The aperture of the boring is narrower than the main chamber and may be circular, oval, or dumb-be ...

'' left by marine ''Lithophaga

''Lithophaga'', the date mussels, are a genus of medium-sized marine bivalve molluscs in the family Mytilidae. Some of the earliest fossil ''Lithophaga'' shells have been found in Mesozoic rocks from the Alps and from Vancouver Island.Ludvigsen, ...

'' bivalve molluscs on three standing marble columns indicated that these columns had remained upright over centuries while the site sank below sea level, then re-emerged. This puzzling feature was the subject of debate in early geology, and eventually led to the identification of bradyseism

Bradyseism is the gradual uplift (positive bradyseism) or descent (negative bradyseism) of part of the Earth's surface caused by the filling or emptying of an underground magma chamber or hydrothermal activity, particularly in volcanic calderas. ...

in the area, showing that the Earth's crust could be subject to gradual movement without destructive earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

s.

Roman origins

The city of Dicaearchia, founded by Greek refugees escaping dictatorship onSamos

Samos (, also ; el, öÈö˜ö¥ö¢ü ) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate ...

, was integrated into the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, ööÝüö¿ö£öçö₤öÝ üâÑö§ â˜üö¥öÝö₤üö§, BasileûÙa tûÇn RhémaûÙén) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

as the city of Puteoli in 194 BC. The macellum

A macellum (plural: ''macella''; ''makellon'') is an ancient Roman indoor market building that sold mostly provisions (especially meat and fish). The building normally sat alongside the forum and basilica, providing a place in which a market coul ...

or food market was built between the late first and early second century AD, and restored during the third century AD under the Severan dynasty

The Severan dynasty was a Ancient Rome, Roman imperial dynasty that ruled the Roman Empire between 193 and 235, during the Roman imperial period (chronology), Roman imperial period. The dynasty was founded by the emperor Septimius Severus (), w ...

.

The building was in the form of an arcaded square courtyard, surrounded by two-storey buildings. Shops lined the marble floored colonnade forming an arcade with 34 grey granite columns. The main entrance and vestibule were positioned on a main axis, which lined up across a tholos in the centre of the square to the exedra

An exedra (plural: exedras or exedrae) is a semicircular architectural recess or platform, sometimes crowned by a semi-dome, and either set into a building's faûÏade or free-standing. The original Greek sense (''Ã¥öƒöÙöÇüöÝ'', a seat out of d ...

for worship which had a portico

A portico is a porch leading to the entrance of a building, or extended as a colonnade, with a roof structure over a walkway, supported by columns or enclosed by walls. This idea was widely used in ancient Greece and has influenced many cult ...

formed by four large cipollino marble

Cipollino marble ("onion-stone") was a variety of marble used by the ancient Greeks and Romans, whose Latin term for it was ''marmor carystium'' (meaning "marble from Karystos"). It was quarried in several locations on the south-west coast of the ...

columns. The exedra had three niches for statues of divinities giving protection to the market, including the sculpture of Serapis

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian deity. The cult of Serapis was promoted during the third century BC on the orders of Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt as a means to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his r ...

. The tholos in the centre of the square was a circular building standing on a podium reached by four symmetrically placed access stairways, with sixteen African marble columns supporting a domed vault. Marine animals decorated friezes around the base of the tholos. The courtyard had four secondary entrances on its longer sides, with latrines in the corners of the colonnade and four (probable) taberna

A ''taberna'' (plural ''tabernae'') was a type of shop or stall in Ancient Rome. Originally meaning a single-room shop for the sale of goods and services, ''tabernae'' were often incorporated into domestic dwellings on the ground level flanking ...

e with their own external entrances as well as access from the arcade.

Excavation and influence on geology

King

King Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

of Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, ööçö˜üö¢ö£ö¿ü, NeûÀpolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

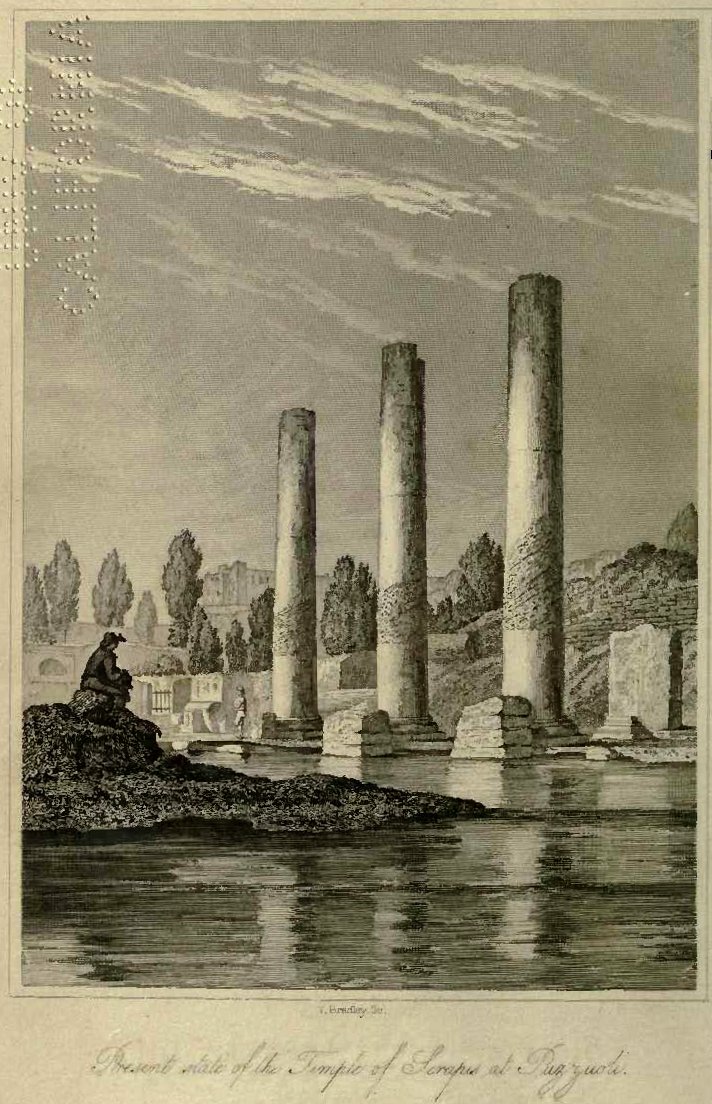

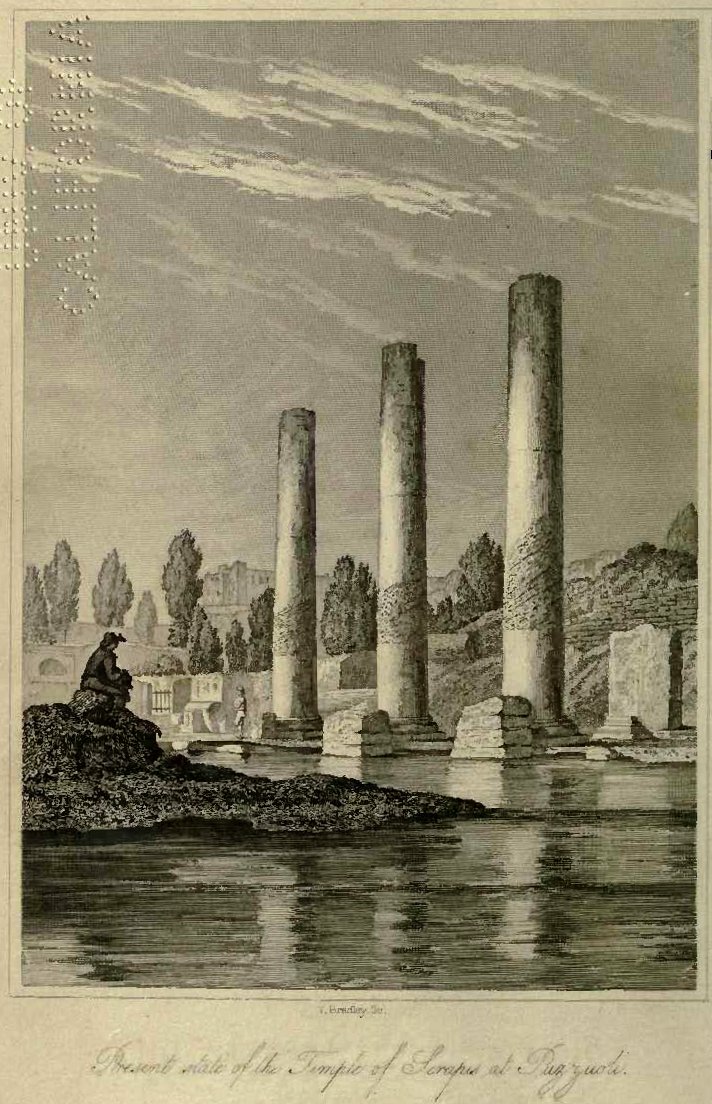

had excavations carried out between 1750 and 1756, exposing the three large cipollino marble columns which gave the site its name of the "three column vineyard". It attracted visits from antiquarians, among them William Hamilton whose ''Campi Phlegraei'' of 1776 showed a distant view of the buildings dry above sea level, and John Soane

Sir John Soane (; nûˋ Soan; 10 September 1753 ã 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neoclassical architecture, Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professo ...

who "Went to the Temple of Jupiter Serapis" on 1 January 1779 and made rough sketches, as well as a plan of the complex, possibly copied from another drawing.

In 1798, Scipione Breislak Scipione Breislak (1748 – 15 February 1826), Italy, Italian geologist of Sweden, Swedish parentage,

was born in Rome in 1748. He distinguished himself as a professor of mathematical and mechanical philosophy in the college of Ragusa, Italy, Ra ...

described his fieldwork at the site in his ''Topografia fisica della Campania'', and theorised about changes in sea level around that coast. He argued that the evidence did not support the suggestion of falling sea levels worldwide, but thought seismic explanations were inadequate as earthquake

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the shaking of the surface of the Earth resulting from a sudden release of energy in the Earth's lithosphere that creates seismic waves. Earthquakes can range in intensity, from ...

s notoriously shook buildings until they collapsed, and the columns were still standing. He concluded that there must have been undetectable movement of the crust of the Earth, but recognised that this was unsatisfactory as the cause could not be seen. In 1802, John Playfair

John Playfair FRSE, FRS (10 March 1748 ã 20 July 1819) was a Church of Scotland minister, remembered as a scientist and mathematician, and a professor of natural philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. He is best known for his book ''Illu ...

, in his ''Illustrations of the Huttonian Theory of the Earth'', used Breislak's descriptions to support James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. ã 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role i ...

's ideas of slow changes, attributing the differing heights of water around the columns to "oscillations" in the level of the land.

Between 1806 and 1818 further excavations exposed the whole of the "Serapeum" or "Temple of Serapis". The excavations lost

Between 1806 and 1818 further excavations exposed the whole of the "Serapeum" or "Temple of Serapis". The excavations lost stratigraphic

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithostrati ...

information in the deposits which had buried the building, but the band of borings or ''gastrochaenolites

''Gastrochaenolites'' is a trace fossil formed as a clavate (club-shaped) boring in a hard substrate such as a shell, rock or carbonate hardground. The aperture of the boring is narrower than the main chamber and may be circular, oval, or dumb-be ...

'' left by marine ''Lithophaga

''Lithophaga'', the date mussels, are a genus of medium-sized marine bivalve molluscs in the family Mytilidae. Some of the earliest fossil ''Lithophaga'' shells have been found in Mesozoic rocks from the Alps and from Vancouver Island.Ludvigsen, ...

'' bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class of marine and freshwater molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hinged parts. As a group, bival ...

s on the three standing marble columns provided a good record of relative sea level variation.

The antiquarian Andrea di Jorio studied the ruins, and in 1817 published a guidebook to the Phlegraean Fields

The Phlegraean Fields ( it, Campi Flegrei ; nap, Campe Flegree, from Ancient Greek 'to burn') is a large region of supervolcanic calderas situated to the west of Naples, Italy. It was declared a regional park in 2003. The area of the calde ...

, with a map of the area which had many hot springs and volcanic craters as well as antiquarian sites including the supposed Temple. By this time the pavement was flooded by the sea, indicating a slight lowering of the land level. In 1820, he published a study of his ''Ricerche sul Tempio di Serapide, in Puzzuoli'', including an illustration based on a drawing by John Izard Middleton showing the three columns with the bands affected by molluscs.

In 1819, Giovanni Battista Brocchi

Giovanni Battista (or Giambattista) Brocchi (18 February 177225 September 1826) was an Italian naturalist, mineralogist and geologist.

Biography

Giovanni Battista Brocchi was born in Bassano del Grappa and studied jurisprudence at the Univers ...

proposed that the columns below the bands had been protected from the molluscs by being buried in silt or volcanic ash. The first volume of ''VerûÊnderungen der ErdoberflûÊche'' by Karl Ernst Adolf von Hoff, published in 1822, included an account of the ruins as demonstrating relative changes in land and sea level. Hoff's second volume of 1824 reviewed how earthquakes might have caused this, and mentioned Jorio's study. Hoff's account motivated Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 ã 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as trea ...

to publish his own idea, coined when he visited the site in 1787. In Goethe's 1823 ''Architektonisch-naturhistorisches Problem'', he suggested that silt or ash had partially buried the columns and at the same time held back water forming a lagoon above sea level. Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson

Robert Jameson FRS FRSE (11 July 1774 ã 19 April 1854) was a Scottish naturalist and mineralogist.

As Regius Professor of Natural History at the University of Edinburgh for fifty years, developing his predecessor John ...

had this paper translated for his Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dû¿n ûideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

journal, to oppose Playfair's views. Other naturalists thought this unlikely, as the fresh water lagoon would not have supported marine molluscs, and the sea was by then higher than at the time of Goethe's visit.

In his 1826 book ''A Description of Active and Extinct Volcanoes'', Charles Daubeny

Charles Giles Bridle Daubeny (11 February 179512 December 1867) was an English chemist, botanist and geologist.

Education

Daubeny was born at Stratton near Cirencester in Gloucestershire, the son of the Rev. James Daubeny. He went to Winchester ...

dismissed the implied sinking of the land by followed by almost as great a rise as unlikely, since "it is probable that not a single pillar of the temple would now retain its erect posture to attest the reality of these convulsions". Daubeny also doubted changing sea levels, so concluded that the bands of holes bored by molluscs must be due to local damming of water around the buildings.

Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 ã 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

's ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830ã1833. Ly ...

'' of 1830 featured as its frontispiece a replication of di Jorio's illustration of the columns (shown above), and a detailed section discussing their significance. He strongly contested Daubeny's argument, and instead proposed slow and steady geological forces. Lyell wrote "That buildings should have been submerged, and afterwards upheaved, without being entirely reduced to a heap of ruins, will appear no anomaly, when we recollect that in the year 1819, when the delta of the Indus sank down, the houses within the fort of Sindree subsided beneath the waves without being overthrown." In 1832 the young Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 ã 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

used Lyell's methods at the first landfall of the ''Beagle'' survey voyage, while considering evidence of land rising up at St. Jago. In his journal, Darwin dismissed Daubeny's argument, and wrote that he felt "sure at St Jago in some places a town might have been raised without injuring a house."

Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage (; 26 December 1791 ã 18 October 1871) was an English polymath. A mathematician, philosopher, inventor and mechanical engineer, Babbage originated the concept of a digital programmable computer.

Babbage is considered ...

carried out a detailed survey of the ruins in 1828 and his ''Observations on the Temple of Serapis at Pozzuoli, near Naples'' were published in 1847. In some of the rooms of the macellum Babbage found a dark brownish encrustation of salts, and a thicker encrustation up to a height of about from floor level. These have been interpreted as showing that as the building lowered, a little lake formed and allowed water to enter the building without there being a direct connection to the sea, then at a later stage the land subsided to the point where sea water came in, and the ''Lithophaga'' started drilling holes in the masonry up to from floor level.

The identification of the building as a macellum

A macellum (plural: ''macella''; ''makellon'') is an ancient Roman indoor market building that sold mostly provisions (especially meat and fish). The building normally sat alongside the forum and basilica, providing a place in which a market coul ...

or marketplace rather than a temple was made by Charles Dubois, who published a detailed account of the ruins of Pozzuoli in his ''Pouzzoles antiques. Histoire et topographie'' of 1907.

Modern investigations

More recent investigations of the vertical movements have shown that the site is near the centre of the Campi Flegrei (Phlegraean Fields

The Phlegraean Fields ( it, Campi Flegrei ; nap, Campe Flegree, from Ancient Greek 'to burn') is a large region of supervolcanic calderas situated to the west of Naples, Italy. It was declared a regional park in 2003. The area of the calde ...

) caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber is ...

and has been subject to repeated "slow earthquakes" or bradyseism

Bradyseism is the gradual uplift (positive bradyseism) or descent (negative bradyseism) of part of the Earth's surface caused by the filling or emptying of an underground magma chamber or hydrothermal activity, particularly in volcanic calderas. ...

of this shallow caldera resulting in relatively slow subsidence over long periods, drowning the ruin, punctuated by periods of relatively rapid uplift that caused it to re-emerge. After a long subsidence through Roman times, there was a period of uplift in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

around AD 700 to 800, then after more subsidence the land rose again from around 1500 up to the last eruption in 1538. The land again subsided gradually, then between 1969 and 1973 the land rose by about . Over the following decade there was a little subsidence, then between 1982 and 1994 there was uplift of almost . Concerns about risks of earthquake damage and possible eruption led to temporary evacuation of the city of Pozzuoli

Pozzuoli (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Naples, in the Italian region of Campania. It is the main city of the Phlegrean Peninsula.

History

Pozzuoli began as the Greek colony of ''Dicaearchia'' ( el, öö¿ö¤öÝö ...

. Detailed measurements indicated that the caldera deformation formed a nearly circular lens centred near Pozzuoli. Various models have been produced to find mechanisms explaining this pattern.

References

Sources

* * * {{Authority control Volcanology History of Earth science Ancient Roman buildings and structures in Pozzuoli