Macedonian issue on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The region of Macedonia is known to have been inhabited since

The region of Macedonia is known to have been inhabited since

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the

After the defeat of

After the defeat of

Taking advantage of the desolation left by the nomadic tribes,

Taking advantage of the desolation left by the nomadic tribes,

The initial period of Ottoman rule led a depopulation of the plains and river valleys of Macedonia. The Christian population there fled to the mountains. Ottomans were largely brought from Asia Minor and settled parts of the region. Towns destroyed in

The initial period of Ottoman rule led a depopulation of the plains and river valleys of Macedonia. The Christian population there fled to the mountains. Ottomans were largely brought from Asia Minor and settled parts of the region. Towns destroyed in

The rise of European nationalism in the 18th century led to the expansion of the Hellenic idea in Macedonia. Its main pillar throughout the centuries of Ottoman rule had been the indigenous Greek population of historical Macedonia. Under the influence of the Greek schools and the

The rise of European nationalism in the 18th century led to the expansion of the Hellenic idea in Macedonia. Its main pillar throughout the centuries of Ottoman rule had been the indigenous Greek population of historical Macedonia. Under the influence of the Greek schools and the

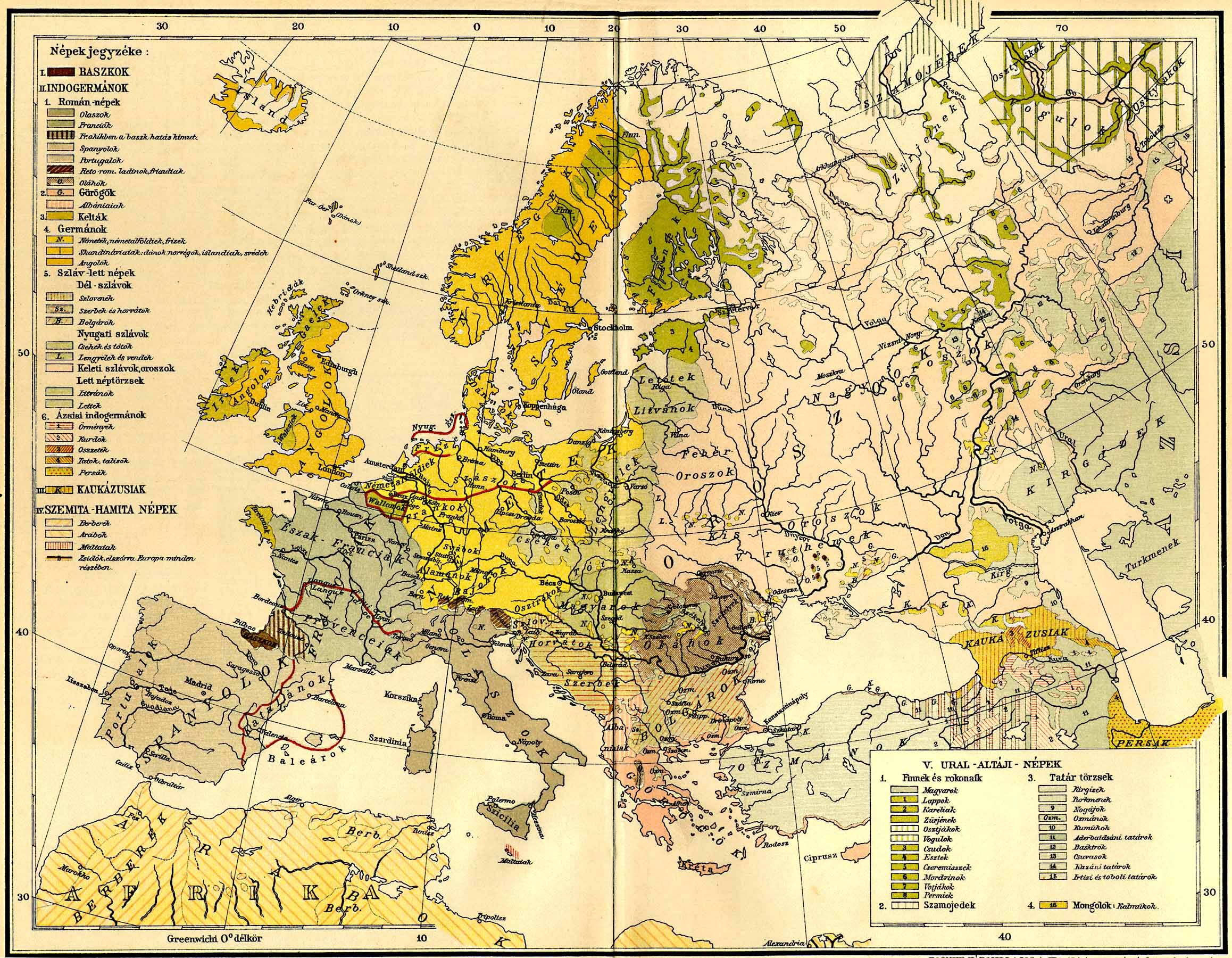

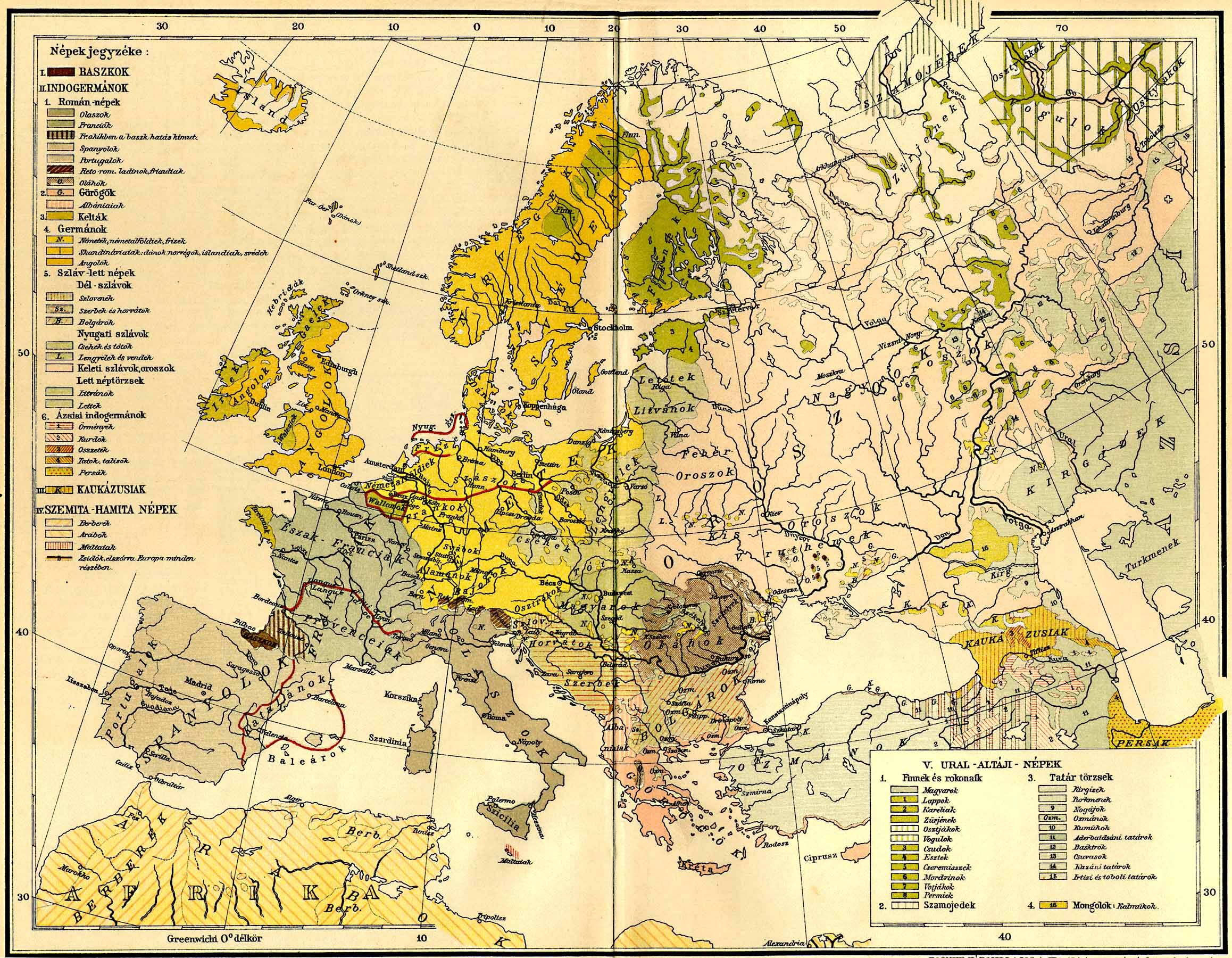

Most of the population of Macedonia was described as Bulgarians during 16th and 17th centuries by Ottoman historians and travellers such as

Most of the population of Macedonia was described as Bulgarians during 16th and 17th centuries by Ottoman historians and travellers such as  European ethnographs and linguists until the

European ethnographs and linguists until the

In Europe, the classic non-national states were the ''multi-ethnic empires'' such as the Ottoman Empire, ruled by a

In Europe, the classic non-national states were the ''multi-ethnic empires'' such as the Ottoman Empire, ruled by a

The

The

Nineteenth century Serbian nationalism viewed Serbs as the people chosen to lead and unite all southern Slavs into one country,

Nineteenth century Serbian nationalism viewed Serbs as the people chosen to lead and unite all southern Slavs into one country,

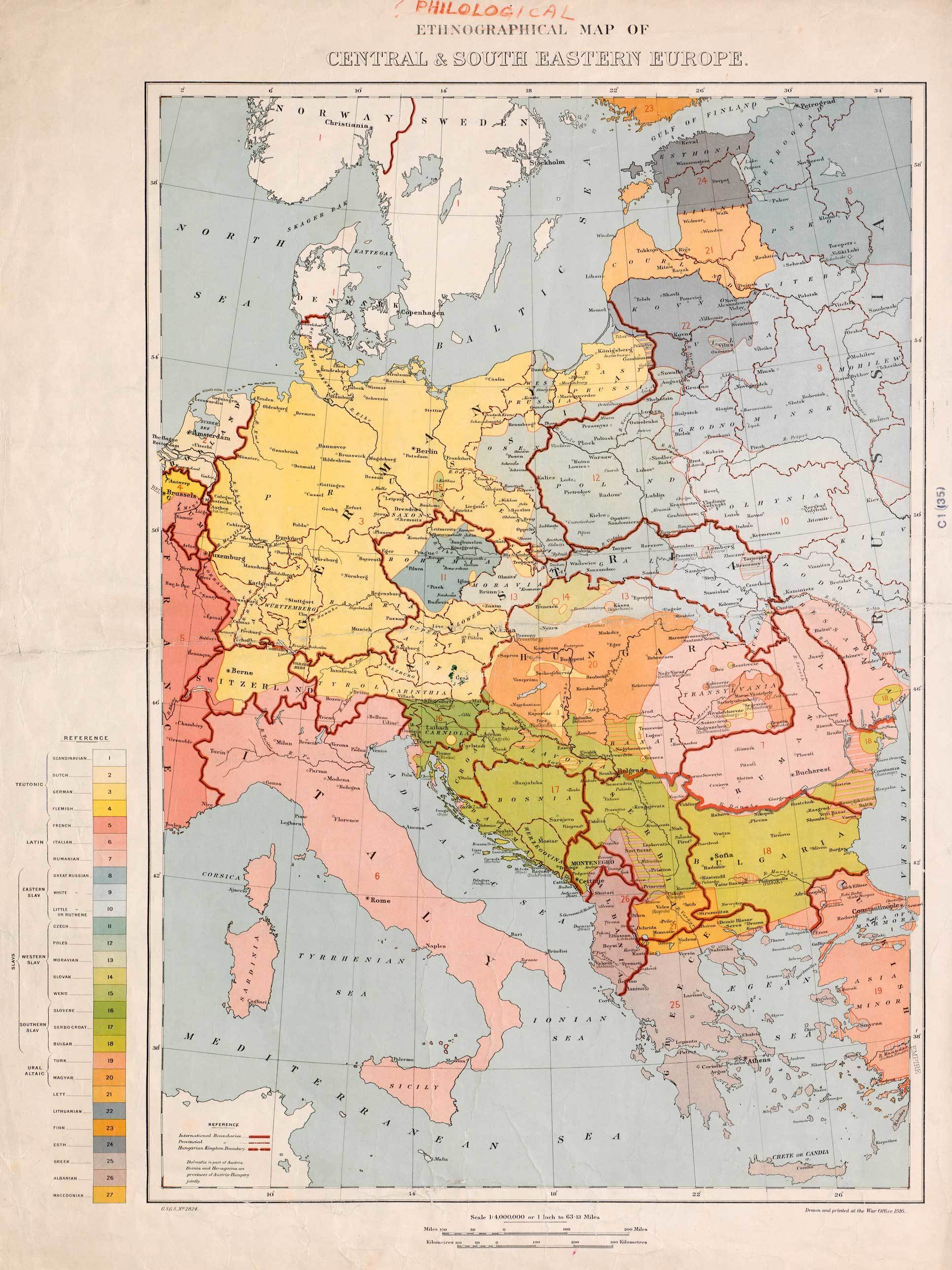

It was established by the end of the 19th century that the majority of the population of central and Southern Macedonia (vilaets of Monastiri and Thessaloniki) were predominantly an ethnic Greek population, while the Northern parts of the region (vilaet of Skopje) were predominantly Slavic. Jews and Ottoman communities were scattered all over. Because of Macedonia's such polyethnic nature, the arguments which Greece used to promote its claim to the whole region were usually of historical and religious character. The Greeks consistently linked nationality to the allegiance to the Patriarchate of Constantinople. "Bulgarophone", "Albanophone" and "Vlachophone" Greeks were coined to describe the population who were Slavic, Albanian or

It was established by the end of the 19th century that the majority of the population of central and Southern Macedonia (vilaets of Monastiri and Thessaloniki) were predominantly an ethnic Greek population, while the Northern parts of the region (vilaet of Skopje) were predominantly Slavic. Jews and Ottoman communities were scattered all over. Because of Macedonia's such polyethnic nature, the arguments which Greece used to promote its claim to the whole region were usually of historical and religious character. The Greeks consistently linked nationality to the allegiance to the Patriarchate of Constantinople. "Bulgarophone", "Albanophone" and "Vlachophone" Greeks were coined to describe the population who were Slavic, Albanian or

The Bulgarian propaganda made a comeback in the 1890s with regard to both education and arms. At the turn of the 20th century there were 785 Bulgarian schools in Macedonia with 1,250 teachers and 39,892 pupils. The Bulgarian Exarchate held jurisdiction over seven dioceses (Skopje,

The Bulgarian propaganda made a comeback in the 1890s with regard to both education and arms. At the turn of the 20th century there were 785 Bulgarian schools in Macedonia with 1,250 teachers and 39,892 pupils. The Bulgarian Exarchate held jurisdiction over seven dioceses (Skopje,

The

The

За Македонските Работи

(''Za Makedonskite Raboti'' – On Macedonian Matters, Sofia, 1903) by

Another prominent activist for the ethnic Macedonian national revival was Dimitrija Čupovski, who was one of the founders and the president of the

Attempts at Romanian influence among the Aromanians and

Attempts at Romanian influence among the Aromanians and

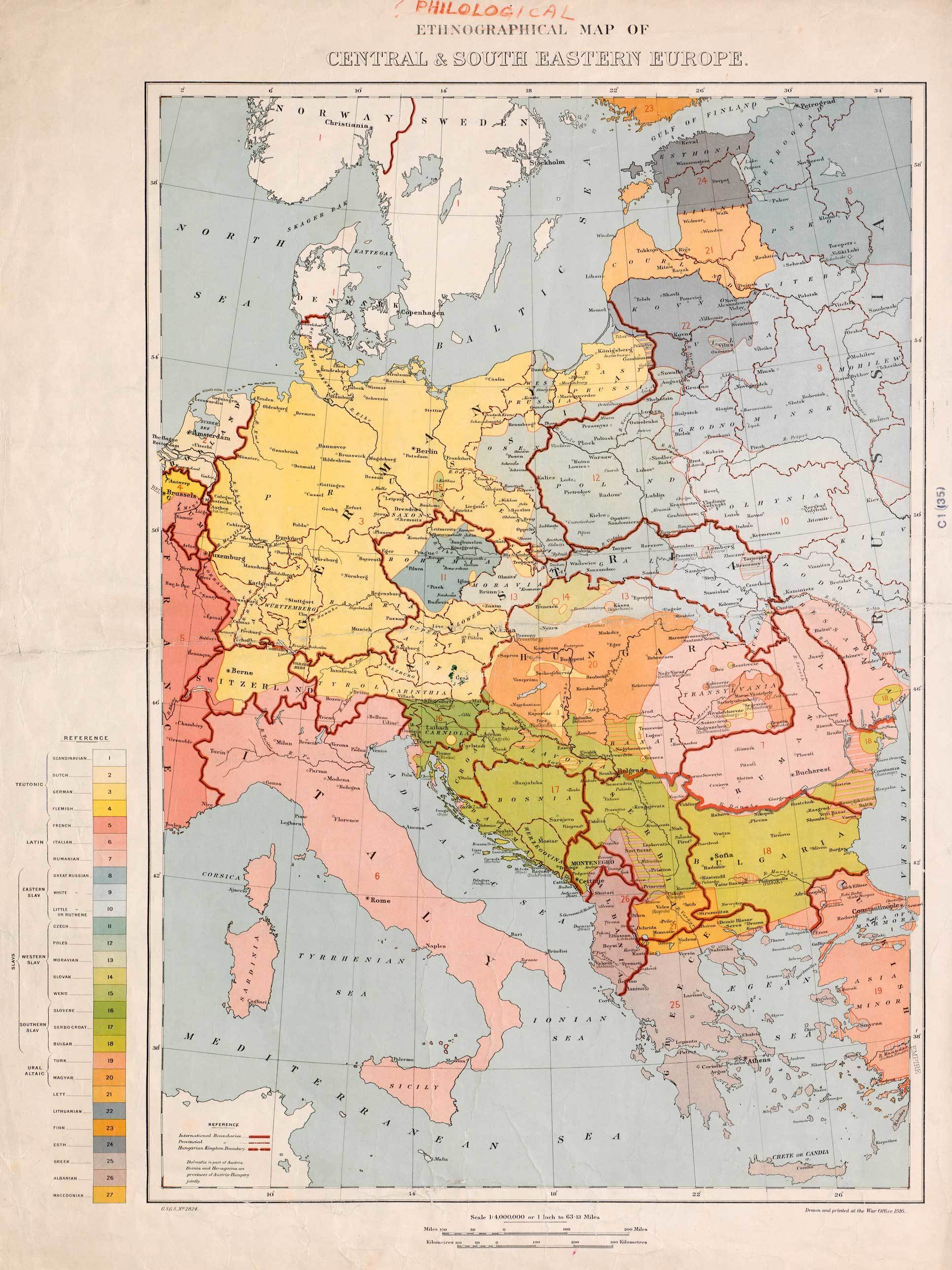

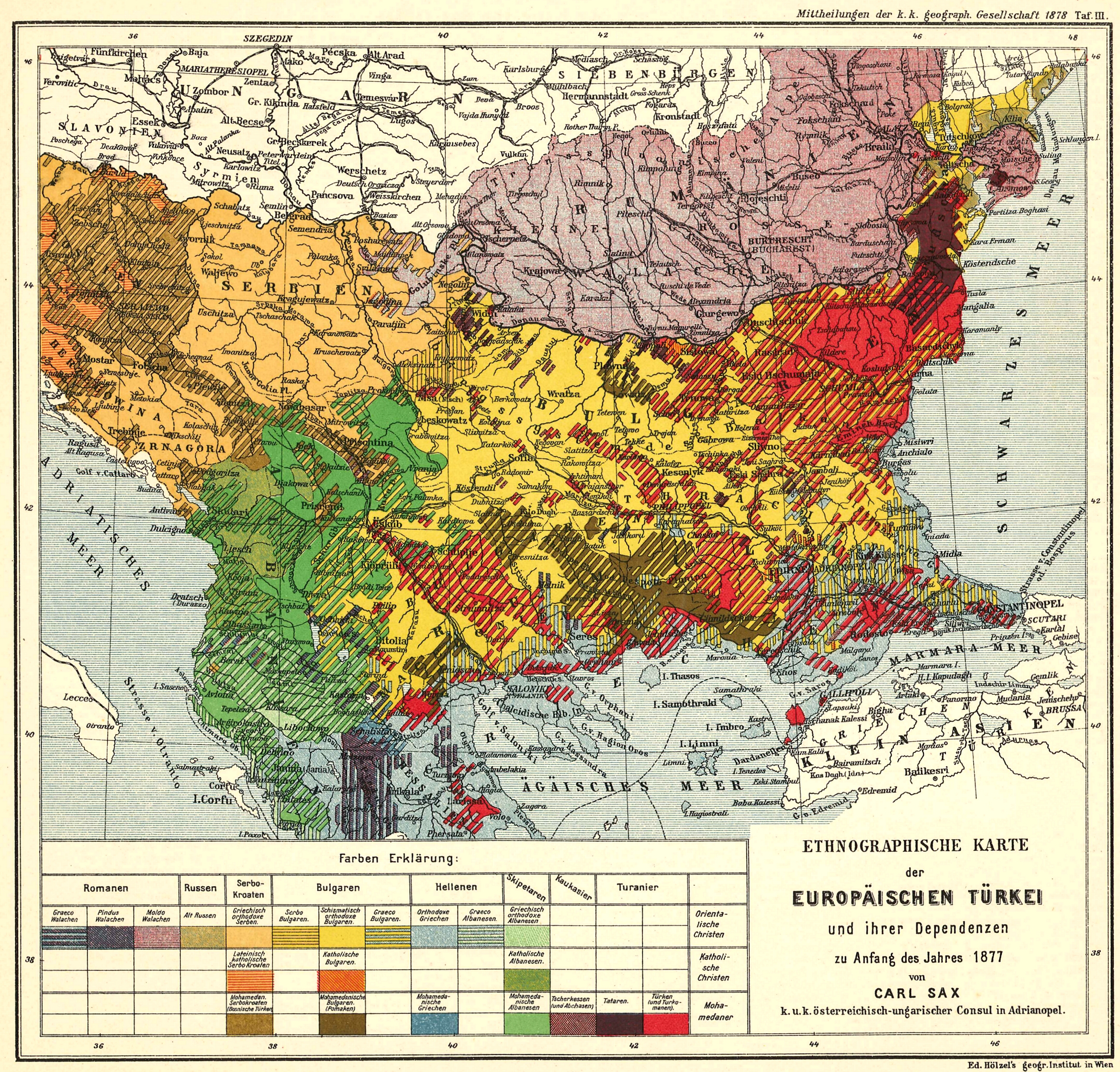

Independent sources in Europe between 1878 and 1918 generally tended to view the Slavic population of Macedonia in two ways: as Bulgarians and as Macedonian Slavs. German scholar

Independent sources in Europe between 1878 and 1918 generally tended to view the Slavic population of Macedonia in two ways: as Bulgarians and as Macedonian Slavs. German scholar

The term "Macedonian Slavs" was used by scholars and publicists in three general meanings:

* as a politically convenient term to define the Slavs of Macedonia without offending Serbian and Bulgarian nationalism;

* as a distinct group of Slavs different from both Serbs and Bulgarians, yet closer to the Bulgarians and having predominantly Bulgarian ethnical and political affinities;

* as a distinct group of Slavs different from both Serbs and Bulgarians having no developed national consciousness and no fast ethnical and political affinities (the definition of Cvijic).

An instance of the use of the first meaning of the term was, for example, the ethnographic map of the Slavic peoples published in (1890) by Russian scholar Zarjanko, which identified the Slavs of Macedonia as Bulgarians. Following an official protest from Serbia the map was later reprinted identifying them under the politically correct name "Macedonian Slavs".

The term was used in a completely different sense by British journalist

The term "Macedonian Slavs" was used by scholars and publicists in three general meanings:

* as a politically convenient term to define the Slavs of Macedonia without offending Serbian and Bulgarian nationalism;

* as a distinct group of Slavs different from both Serbs and Bulgarians, yet closer to the Bulgarians and having predominantly Bulgarian ethnical and political affinities;

* as a distinct group of Slavs different from both Serbs and Bulgarians having no developed national consciousness and no fast ethnical and political affinities (the definition of Cvijic).

An instance of the use of the first meaning of the term was, for example, the ethnographic map of the Slavic peoples published in (1890) by Russian scholar Zarjanko, which identified the Slavs of Macedonia as Bulgarians. Following an official protest from Serbia the map was later reprinted identifying them under the politically correct name "Macedonian Slavs".

The term was used in a completely different sense by British journalist

The name "Macedonian Slavs" started to appear in publications at the end of the 1880s and the beginning of the 1890s. Though the successes of the Serbian propaganda effort had proved that the Slavic population of Macedonia was not only Bulgarian, they still failed to convince that this population was, in fact, Serbian. Rarely used until the end of the 19th century compared to 'Bulgarians', the term 'Macedonian Slavs' served more to conceal rather than define the national character of the population of Macedonia. Scholars resorted to it usually as a result of Serbian pressure or used it as a general term for the Slavs inhabiting Macedonia regardless of their ethnic affinities. The Serbian politician

The name "Macedonian Slavs" started to appear in publications at the end of the 1880s and the beginning of the 1890s. Though the successes of the Serbian propaganda effort had proved that the Slavic population of Macedonia was not only Bulgarian, they still failed to convince that this population was, in fact, Serbian. Rarely used until the end of the 19th century compared to 'Bulgarians', the term 'Macedonian Slavs' served more to conceal rather than define the national character of the population of Macedonia. Scholars resorted to it usually as a result of Serbian pressure or used it as a general term for the Slavs inhabiting Macedonia regardless of their ethnic affinities. The Serbian politician

The region of Macedonia is known to have been inhabited since

The region of Macedonia is known to have been inhabited since Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

times.

Еarliest historical inhabitants

The earliest historical inhabitants of the region were thePelasgians

The name Pelasgians ( grc, Πελασγοί, ''Pelasgoí'', singular: Πελασγός, ''Pelasgós'') was used by classical Greek writers to refer either to the predecessors of the Greeks, or to all the inhabitants of Greece before the emergenc ...

, the Bryges

Bryges or Briges ( el, Βρύγοι or Βρίγες) is the historical name given to a people of the ancient Balkans. They are generally considered to have been related to the Phrygians, who during classical antiquity lived in western Anatolia. Bot ...

and the Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. ...

. The Pelasgians occupied Emathia

Emathia ( gr, Ἠμαθία) was the name of the plain opposite the Thermaic Gulf when the kingdom of Macedon was formed. The name was used to define the area between the rivers Aliakmon and Loudias, which, because it was the center of the kingdom ...

and the Bryges occupied northern Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich ...

, as well as Macedonia, mainly west of the Axios River

The Vardar (; mk, , , ) or Axios () is the longest river in North Macedonia and the second longest river in Greece, in which it reaches the Aegean Sea at Thessaloniki. It is long, out of which are in Greece, and drains an area of around . Th ...

and parts of Mygdonia

Mygdonia (; el, Μυγδονία / Μygdonia) was an ancient territory, part of Ancient Thrace, later conquered by Macedon, which comprised the plains around Therma (Thessalonica) together with the valleys of Klisali and Besikia, including the ...

. Thracians, in early times occupied mainly the eastern parts of Macedonia, (Mygdonia

Mygdonia (; el, Μυγδονία / Μygdonia) was an ancient territory, part of Ancient Thrace, later conquered by Macedon, which comprised the plains around Therma (Thessalonica) together with the valleys of Klisali and Besikia, including the ...

, Crestonia

Crestonia (or Crestonice) ( el, Κρηστωνία) was an ancient region immediately north of Mygdonia. The Echeidorus river, which flowed through Mygdonia into the Thermaic Gulf, had its source in Crestonia. It was partly occupied by a remnant o ...

, Bisaltia

Bisaltia ( el, Βισαλτία) or Bisaltica was an ancient country which was bordered by Sintice on the north, Crestonia on the west, Mygdonia on the south and was separated by Odomantis on the north-east and Edonis on the south-east by river ...

). The Ancient Macedonians

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain around the rivers Haliacmon and lower Vardar, Axios in the northeastern part of Geography of Greece#Mainland, mainland Greece. Es ...

are missing from early historical accounts because they had been living in the southern extremities of the region – the Orestian highlands – since before the Dark Ages. The Macedonian tribes subsequently moved down from Orestis in the upper Haliacmon due to pressure from the Orestae

Orestis (Greek: Ορέστης) was a region of Upper Macedonia, corresponding roughly to the modern Kastoria regional unit located in West Macedonia, Greece. Its inhabitants were the Orestae, an ancient Greek tribe that was part of the Molossi ...

.

Ancient Macedonians

The name of the region of Macedonia ( el, Μακεδονία, ''Makedonia'') derives from the tribal name of the ancient Macedonians ( el, Μακεδώνες, ''Makedónes''). According to theGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

historian Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

, the ''Makednoi'' ( el, Mακεδνοί) were a Dorian tribe that stayed behind during the great southward migration of the Dorian Greeks

The Dorians (; el, Δωριεῖς, ''Dōrieîs'', singular , ''Dōrieús'') were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans, and Ionians) ...

.The word "Makednos" is cognate with the Doric Greek

Doric or Dorian ( grc, Δωρισμός, Dōrismós), also known as West Greek, was a group of Ancient Greek dialects; its varieties are divided into the Doric proper and Northwest Doric subgroups. Doric was spoken in a vast area, that included ...

word "Μάκος" ''Μakos'' (Attic

An attic (sometimes referred to as a '' loft'') is a space found directly below the pitched roof of a house or other building; an attic may also be called a ''sky parlor'' or a garret. Because attics fill the space between the ceiling of the ...

form Μήκος – "mékos"), which is Greek for "length". The ancient Macedonians took this name either because they were physically tall, or because they settled in the mountains. The latter definition would translate "Macedonian" as "Highlander".

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the

The Macedonians ( el, Μακεδόνες, ''Makedónes'') were an ancient tribe that lived on the alluvial plain

An alluvial plain is a largely flat landform created by the deposition of sediment over a long period of time by one or more rivers coming from highland regions, from which alluvial soil forms. A floodplain is part of the process, being the sma ...

around the rivers Haliacmon

The Haliacmon ( el, Αλιάκμονας, ''Aliákmonas''; formerly: , ''Aliákmon'' or ''Haliákmōn'') is the longest river flowing entirely in Greece, with a total length of . In Greece there are three rivers longer than Haliakmon, Maritsa ( el ...

and lower Axios Axios commonly refers to:

* Axios (river), a river that runs through Greece and North Macedonia

* ''Axios'' (website), an American news and information website

Axios may also refer to:

Brands and enterprises

* Axios, a brand of suspension produ ...

in the northeastern part of mainland Greece

Greece is a country of the Balkans, in Southeastern Europe, bordered to the north by Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria; to the east by Turkey, and is surrounded to the east by the Aegean Sea, to the south by the Cretan and the Libyan Seas, an ...

. Essentially an ancient Greek people,; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; . they gradually expanded from their homeland along the Haliacmon valley on the northern edge of the Greek world, absorbing or driving out neighbouring non-Greek tribes, primarily Thracian

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied t ...

and Illyrian. They spoke Ancient Macedonian, which was either a sibling language to Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

or a Doric Greek

Doric or Dorian ( grc, Δωρισμός, Dōrismós), also known as West Greek, was a group of Ancient Greek dialects; its varieties are divided into the Doric proper and Northwest Doric subgroups. Doric was spoken in a vast area, that included ...

dialect, although the prestige language

Prestige refers to a good reputation or high esteem; in earlier usage, ''prestige'' meant "showiness". (19th c.)

Prestige may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Films

* ''Prestige'' (film), a 1932 American film directed by Tay Garnett ...

of the region was at first Attic

An attic (sometimes referred to as a '' loft'') is a space found directly below the pitched roof of a house or other building; an attic may also be called a ''sky parlor'' or a garret. Because attics fill the space between the ceiling of the ...

and then Koine Greek

Koine Greek (; Koine el, ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, hē koinè diálektos, the common dialect; ), also known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-reg ...

. Their religious beliefs mirrored those of other Greeks, following the main deities of the Greek pantheon

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities of d ...

, although the Macedonians continued Archaic burial practices that had ceased in other parts of Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

after the 6th century BC. Aside from the monarchy, the core of Macedonian society was its nobility. Similar to the aristocracy of neighboring Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

, their wealth was largely built on herding horses

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

and cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult mal ...

.

Although composed of various clans, the kingdom of Macedonia

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

, established around the 8th century BC, is mostly associated with the Argead dynasty and the tribe named after it. The dynasty was allegedly founded by Perdiccas I

Perdiccas I ( gr, Περδίκκας, Perdíkkas) was king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia. He ruled somewhere between 650 BC and 620 BC.

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from ...

, descendant of the legendary Temenus

In Greek mythology, Temenus ( el, Τήμενος, ''Tḗmenos'') was a son of Aristomachus and brother of Cresphontes and Aristodemus.

Temenus was a great-great-grandson of Heracles and helped lead the fifth and final attack on Mycenae in the ...

of Argos

Argos most often refers to:

* Argos, Peloponnese, a city in Argolis, Greece

** Ancient Argos, the ancient city

* Argos (retailer), a catalogue retailer operating in the United Kingdom and Ireland

Argos or ARGOS may also refer to:

Businesses

...

, while the region of Macedon perhaps derived its name from Makedon, a figure of Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the Cosmogony, origin and Cosmology#Metaphysical co ...

. Traditionally ruled by independent families, the Macedonians seem to have accepted Argead rule by the time of Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

(). Under Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

(), the Macedonians are credited with numerous military innovations, which enlarged their territory and increased their control over other areas extending into Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

. This consolidation of territory allowed for the exploits of Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

(), the conquest of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

, the establishment of the diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The War ...

successor state

Succession of states is a concept in international relations regarding a successor state that has become a sovereign state over a territory (and populace) that was previously under the sovereignty of another state. The theory has its roots in 19th- ...

s, and the inauguration of the Hellenistic period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in 3 ...

in West Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, and the broader Mediterranean world

The history of the Mediterranean region and of the cultures and people of the Mediterranean Basin is important for understanding the origin and development of the Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Canaanite, Phoenician, Hebrew, Carthaginian, Minoan, Gre ...

. The Macedonians were eventually conquered by the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

, which dismantled the Macedonian monarchy at the end of the Third Macedonian War

The Third Macedonian War (171–168 BC) was a war fought between the Roman Republic and King Perseus of Macedon. In 179 BC, King Philip V of Macedon died and was succeeded by his ambitious son Perseus. He was anti-Roman and stirred anti-Roman f ...

(171–168 BC) and established the Roman province

The Roman provinces (Latin: ''provincia'', pl. ''provinciae'') were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was rule ...

of Macedonia after the Fourth Macedonian War

The Fourth Macedonian War (150–148 BC) was fought between Macedon, led by the pretender Andriscus, and the Roman Republic. It was the last of the Macedonian Wars, and was the last war to seriously threaten Roman control of Greece until the Fi ...

(150–148 BC).

Before the reign of Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon 495–454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Pope Alexander I (died 115), early bishop of Rome

* Pope Alexander I of Alexandria (died 320s), patriarch of ...

, father of Perdiccas II

Perdiccas II ( gr, Περδίκκας, Perdíkkas) was a king of Macedonia from c. 448 BC to c. 413 BC. During the Peloponnesian War, he frequently switched sides between Sparta and Athens.

Family

Perdiccas II was the son of Alexander I, he had ...

, the ancient Macedonians lived mostly on lands adjacent to the Haliakmon, in the far south of the modern Greek province of Macedonia. Alexander is credited with having added to Macedonia many of the lands that would become part of the core Macedonian territory: Pieria, Bottiaia, Mygdonia, and Eordaia (Thuc. 2.99). Anthemus, Crestonia, and Bisaltia also seem to have been added during his reign (Thuc. 2.99). Most of these lands were previously inhabited by Thracian tribes, and Thucydides records how the Thracians were pushed to the mountains when the Macedonians acquired their lands.

Generations after Alexander, Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

would add new lands to Macedonia, and also reduce neighboring powers such as the Illyrians and Paeonians, who had attacked him when he became king, to semi-autonomous peoples. In Philip's time, Macedonians expanded and settled in many of the new adjoining territories, and Thrace up to the Nestus

Nestos ( ), Mesta ( ), or formerly the Mesta Karasu in Turkish (Karasu meaning "black river"), is a river in Bulgaria and Greece. It rises in the Rila Mountains and flows into the Aegean Sea near the island of Thasos. It plunges down towering ca ...

was colonized by Macedonian settlers. Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

however testifies that the bulk of the population inhabiting in Upper Macedonia remained of Thraco-Illyrian

The term Thraco-Illyrian refers to a hypothesis according to which the Daco-Thracian and Illyrian languages comprise a distinct branch of Indo-European. Thraco-Illyrian is also used as a term merely implying a Thracian- Illyrian interference, mix ...

stock. Philip's son, Alexander the Great, extended Macedonian power over key Greek city-states, and his campaigns, both local and abroad, would make the Macedonian power supreme from Greece, to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, and the edge of India.

Following this period there were repeated barbaric invasions of the Balkans by Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancien ...

.

Roman Macedonia

Andriscus

Andriscus ( grc, Ἀνδρίσκος, ''Andrískos''; 154/153 BC – 146 BC), also often referenced as Pseudo-Philip, was a Greek pretender who became the last independent king of Macedon in 149 BC as Philip VI ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος, ''Phil ...

in 148 BC, Macedonia officially became a province of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kin ...

in 146 BC. Hellenization of the non-Greek population was not yet complete in 146 BC, and many of the Thracian and Illyrian tribes had preserved their languages. It is also possible that the ancient Macedonian tongue was still spoken, alongside Koine

Koine Greek (; Koine el, ἡ κοινὴ διάλεκτος, hē koinè diálektos, the common dialect; ), also known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-reg ...

, the common Greek language of the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

era. From an early period, the Roman province of Macedonia included Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinrich ...

, Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

, parts of Thrace and Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

, thus making the region of Macedonia permanently lose any connection with its ancient borders, and now be the home of a greater variety of inhabitants.

Byzantine Macedonia

As the Greek state ofByzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

gradually emerged as a successor state to the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

, Macedonia became one of its most important provinces as it was close to the Empire's capital (Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

) and included its second largest city (Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

). According to Byzantine maps that were recorded by Ernest Honigmann, by the 6th century AD there were two provinces carrying the name "Macedonia" in the Empire's borders:

*Macedonia Prima ("First Macedonia")

: encompassing most of the kingdom of Macedonia, coinciding with most of the modern Greek region of Macedonia, and had Thessalonica as its capital.

*Macedonia Salutaris ("Wholesome Macedonia"), also known as Macedonia Secunda ("Second Macedonia")

: partially encompassing both Pelagonia and Dardania and containing the whole of Paeonia. The province mostly coincides with the present-day North Macedonia. The town of Stobi located to the junction of the Crna Reka and Vardar rivers, the former capital of Paeonia, became the provincial capital.

Macedonia was ravaged several times in the 4th and the 5th century by desolating onslaughts of Visigoths

The Visigoths (; la, Visigothi, Wisigothi, Vesi, Visi, Wesi, Wisi) were an early Germanic people who, along with the Ostrogoths, constituted the two major political entities of the Goths within the Roman Empire in late antiquity, or what is ...

, Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

and Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

. These did little to change its ethnic composition (the region being almost completely populated by Greeks or Hellenized

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the ...

people by that time) but left much of the region depopulated.

Later in about 800 AD, a new province of the Byzantine Empire – Macedonia, was organised by Empress Irene

Irene of Athens ( el, Εἰρήνη, ; 750/756 – 9 August 803), surname Sarantapechaina (), was Byzantine empress consort to Emperor Leo IV from 775 to 780, regent during the childhood of their son Constantine VI from 780 until 790, co-ruler ...

out of the Theme of Thrace. It had no relation with the historical or geographical region of Macedonia, but instead it was centered in Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

, including the area from Adrianople

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

(the theme's capital) and the Evros valley eastward along the Sea of Marmara

The Sea of Marmara,; grc, Προποντίς, Προποντίδα, Propontís, Propontída also known as the Marmara Sea, is an inland sea located entirely within the borders of Turkey. It connects the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea via the ...

. It did not include any part of ancient Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

, which (insofar as the Byzantines controlled it) was in the Theme of Thessalonica.

Middle Ages

Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

settled in the Balkan Peninsula from the 6th century AD

''(see also: South Slavs

South Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak South Slavic languages and inhabit a contiguous region of Southeast Europe comprising the eastern Alps and the Balkan Peninsula. Geographically separated from the West Slavs and East Slavs by Austria, Hu ...

)''. Aided by the Avars and by Turkic Bulgars

The Bulgars (also Bulghars, Bulgari, Bolgars, Bolghars, Bolgari, Proto-Bulgarians) were Turkic semi-nomadic warrior tribes that flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region during the 7th century. They became known as nomad ...

, Slavic tribes in the 6th century started a gradual invasion into the lands of Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

. They infiltrated into Macedonia and reached as far south as Thessaly and the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese (), Peloponnesus (; el, Πελοπόννησος, Pelopónnēsos,(), or Morea is a peninsula and geographic regions of Greece, geographic region in southern Greece. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmu ...

, settling in isolated regions that the Byzantines called ''Sclavinias'', until they were gradually pacified. Many Slavs came to serve as soldiers in Byzantine armies and settled in other parts of the Byzantine Empire. Slavic settlers assimilated many among the Romanised and Hellenised Paeonian, Illyrian and Thracian population of Macedonia, but pockets of tribes that fled to the mountains remained independent. A number of scholars today consider that present-day Aromanians

The Aromanians ( rup, Armãnji, Rrãmãnji) are an Ethnic groups in Europe, ethnic group native to the southern Balkans who speak Aromanian language, Aromanian, an Eastern Romance language. They traditionally live in central and southern Alba ...

(Vlachs), Sarakatsani

The Sarakatsani ( el, Σαρακατσάνοι, also written Karakachani, bg, каракачани) are an ethnic Greek population subgroup who were traditionally transhumant shepherds, native to Greece, with a smaller presence in neighbouring ...

and Albanians

The Albanians (; sq, Shqiptarët ) are an ethnic group and nation native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, culture, history and language. They primarily live in Albania, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Se ...

originate from these mountainous populations. The interaction between Romanised and non-Romanised indigenous peoples and the Slavs resulted in linguistic similarities which are reflected in modern Bulgarian

Bulgarian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Bulgaria

* Bulgarians, a South Slavic ethnic group

* Bulgarian language, a Slavic language

* Bulgarian alphabet

* A citizen of Bulgaria, see Demographics of Bulgaria

* Bul ...

, Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

, Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

and Macedonian, all of them members of the Balkan language area. The Slavs also occupied the hinterland of Thessaloniki, launching consecutive attacks on the city in 584, 586, 609, 620, and 622 AD, but never taking it. Detachments of Avars often joined the Slavs in their onslaughts, but the Avars did not form any lasting settlements in the region. A branch of the Bulgars led by khan Kuber

Kuber, (also Kouber or Kuver), was a Bulgar leader who, according to the ''Miracles of Saint Demetrius'', liberated a mixed Bulgar and Byzantine Christian population in the 670s, whose ancestors had been transferred from the Eastern Roman Empi ...

, however, settled in western Macedonia and eastern Albania around 680 AD and also engaged in attacks on Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' cont ...

together with the Slavs

Slavs are the largest European ethnolinguistic group. They speak the various Slavic languages, belonging to the larger Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout northern Eurasia, main ...

. By this time, several different ethnicities inhabited the whole Macedonia region, with South Slavs forming the overall majority in the northern fringes of Macedonia while Greeks dominated the highlands of western Macedonia, the central plains, and the coastline.

At the beginning of the 9th century, Bulgaria conquered the Northern Byzantine lands, including Macedonia B and part of Macedonia A. Those regions remained under Bulgarian rule for two centuries, until the destruction of Bulgaria by the Byzantine Emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Βασίλειος Πορφυρογέννητος ;) and, most often, the Purple-born ( gr, ὁ πορφυρογέννητος, translit=ho porphyrogennetos).. 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar S ...

(nicknamed "the Bulgar-slayer") in 1018.

In the 11th and the 12th centuries, the first historical mention occurs of two ethnic groups just off the borders of Macedonia: the Arvanites

Arvanites (; Arvanitika: , or , ; Greek: , ) are a bilingual population group in Greece of Albanian origin. They traditionally speak Arvanitika, an Albanian language variety, along with Greek. Their ancestors were first recorded as settlers ...

in modern Albania and the Vlachs (Aromanians) in Thessaly and Pindus. Modern historians are divided as to whether the Albanians came to the area then (from Dacia

Dacia (, ; ) was the land inhabited by the Dacians, its core in Transylvania, stretching to the Danube in the south, the Black Sea in the east, and the Tisza in the west. The Carpathian Mountains were located in the middle of Dacia. It thus r ...

or Moesia) or originated from the native non-Romanized Thracian or Illyrian populations.

Also in the 11th century Byzantium settled several tens of thousands of Turkic Christians from Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, referred to as Vardariotes, along the lower course of the Vardar. Colonies of other Turkic tribes such as Uzes, Petchenegs, and Cumans were also introduced at various periods from the 11th to the 13th century. All these were eventually Hellenized or Bulgarized. Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

, migrating from north India, reached the Balkans - including Macedonia - around the 14th century, with some of them settling there. Successive waves of Romani immigration occurred in the 15th and the 16th century, too. ''(See also: Roma in the Republic of Macedonia

According to the last census from 2002, there were 53,879 people counted as Romani, the majority are Muslim Romani people in what is now North Macedonia, or 2.66% of the population. Another 3,843 people have been counted as "Egyptians" (0.2%).

...

)''

In the 13th and the 14th centuries the Byzantine Empire, the Despotate of Epirus

The Despotate of Epirus ( gkm, Δεσποτᾶτον τῆς Ἠπείρου) was one of the Greek successor states of the Byzantine Empire established in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 by a branch of the Angelos dynasty. It claim ...

, the rulers of Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

, and the Bulgarian Empire

In the medieval history of Europe, Bulgaria's status as the Bulgarian Empire ( bg, Българско царство, ''Balgarsko tsarstvo'' ) occurred in two distinct periods: between the seventh and the eleventh centuries and again between the ...

contested for control of the region of Macedonia, but the frequent shift of borders did not result in any major population changes. In 1338 the Serbian Empire

The Serbian Empire ( sr, / , ) was a medieval Serbian state that emerged from the Kingdom of Serbia. It was established in 1346 by Dušan the Mighty, who significantly expanded the state.

Under Dušan's rule, Serbia was the major power in the ...

conquered the area, but after the Battle of Maritsa in 1371 most of the Serbian lords of Macedonia acknowledged Ottoman suzerainty. After the conquest of Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; r ...

by the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

in 1392, most of Macedonia formally became incorporated into the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

.

Ottoman rule

Muslims and Christians

The initial period of Ottoman rule led a depopulation of the plains and river valleys of Macedonia. The Christian population there fled to the mountains. Ottomans were largely brought from Asia Minor and settled parts of the region. Towns destroyed in

The initial period of Ottoman rule led a depopulation of the plains and river valleys of Macedonia. The Christian population there fled to the mountains. Ottomans were largely brought from Asia Minor and settled parts of the region. Towns destroyed in Vardar Macedonia

Vardar Macedonia ( Macedonian and sr, Вардарска Македонија, ''Vardarska Makedonija'') was the name given to the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia (1912–1918) and Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1918–1941) roughly corresponding to t ...

during the conquest were renewed, this time populated exclusively by Muslims. The Ottoman element in Macedonia was especially strong in the 17th and the 18th century with travellers defining the majority of the population, especially the urban one, as Muslim. The Ottoman population, however, sharply declined at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century on account of the incessant wars led by the Ottoman Empire, the low birth rate and the higher death toll of the frequent plague epidemics among Muslims than among Christians.

The Ottoman–Habsburg War (1683–1699), the subsequent flight of a substantial part of the Serbian population in Kosovo

Kosovo ( sq, Kosova or ; sr-Cyrl, Косово ), officially the Republic of Kosovo ( sq, Republika e Kosovës, links=no; sr, Република Косово, Republika Kosovo, links=no), is a partially recognised state in Southeast Euro ...

to Austria and the reprisals and looting during the Ottoman counteroffensive led to an influx of Albanian Muslims into Kosovo, northern and northwestern Macedonia. Being in the position of power, the Albanian Muslims managed to push out their Christian neighbours and conquered additional territories in the 18th and the 19th centuries. Pressures from central government following the first Russo-Turkish war that ended in 1774 and in which Ottoman Greeks were implicated as a "fifth column" led to the superficial Islamization of several thousand Greek-speakers in western Macedonia. These Greek Muslims

Greek Muslims, also known as Grecophone Muslims, are Muslims of Greek ethnic origin whose adoption of Islam (and often the Turkish language and identity) dates to the period of Ottoman rule in the southern Balkans. They consist primarily of th ...

retained their Greek language and identity, remained Crypto-Christians

Crypto-Christianity is the secret practice of Christianity, usually while attempting to camouflage it as another faith or observing the rituals of another religion publicly. In places and time periods where Christians were persecuted or Christiani ...

, and were subsequently called Vallahades The Vallahades ( el, Βαλαχάδες) or Valaades ( el, Βαλαάδες) were a Muslim Macedonian Greek population who lived along the river Haliacmon in southwest Greek Macedonia, in and around Anaselitsa (modern Neapoli) and Grevena. They n ...

by local Greek Orthodox Christians because apparently the only Turkish-Arabic they ever bothered to learn was how to say "wa-llahi" or "by Allah". The destruction and abandoning of the Christian Aromanian city of Moscopole

Moscopole or Voskopoja ( sq, Voskopojë; rup, Moscopole, with several other variants; el, Μοσχόπολις, Moschopolis) is a village in Korçë County in southeastern Albania. During the 18th century, it was the cultural and commercial ...

and other important Aromanian settlements in the southern Albania (Epirus-Macedonia) region in the second half of the 18th century caused a large-scale migration of thousands of Aromanians to the cities and villages of Western Macedonia, most notably to Bitola

Bitola (; mk, Битола ) is a city in the southwestern part of North Macedonia. It is located in the southern part of the Pelagonia valley, surrounded by the Baba, Nidže, and Kajmakčalan mountain ranges, north of the Medžitlija-Níki ...

, Krushevo and surrounding regions. Thessaloniki also became the home of a large Jewish population following Spain's expulsions of Jews after 1492. The Jews later formed small colonies in other Macedonian cities, most notably Bitola and Serres

Sérres ( el, Σέρρες ) is a city in Macedonia, Greece, capital of the Serres regional unit and second largest city in the region of Central Macedonia, after Thessaloniki.

Serres is one of the administrative and economic centers of Northe ...

.

Hellenic idea

The rise of European nationalism in the 18th century led to the expansion of the Hellenic idea in Macedonia. Its main pillar throughout the centuries of Ottoman rule had been the indigenous Greek population of historical Macedonia. Under the influence of the Greek schools and the

The rise of European nationalism in the 18th century led to the expansion of the Hellenic idea in Macedonia. Its main pillar throughout the centuries of Ottoman rule had been the indigenous Greek population of historical Macedonia. Under the influence of the Greek schools and the Patriarchate of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople ( el, Οἰκουμενικὸν Πατριαρχεῖον Κωνσταντινουπόλεως, translit=Oikoumenikón Patriarkhíon Konstantinoupóleos, ; la, Patriarchatus Oecumenicus Constanti ...

, however, it started to spread among the other orthodox subjects of the Empire as the urban Christian population of Slavic and Albanian origin started to view itself increasingly as Greek. The Greek language

Greek ( el, label=Modern Greek, Ελληνικά, Elliniká, ; grc, Ἑλληνική, Hellēnikḗ) is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Italy (Calabria and Salento), southern Al ...

became a symbol of civilization and a basic means of communication between non-Muslims. The process of Hellenization was additionally reinforced after the abolition of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

The Archbishopric of Ohrid, also known as the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

*T. Kamusella in The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe, Springer, 2008, p. 276

*Aisling Lyon, Decentralisation and the Management of Ethni ...

in 1767. Though with a predominantly Greek clergy, the Archbishopric did not yield to the direct order of Constantinople and had autonomy in many vital domains. However, the poverty of the Christian peasantry and the lack of proper schooling in villages preserved the linguistic diversity of the Macedonian countryside. The Hellenic idea reached its peak during the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

(1821–1829) which received the active support of the Greek Macedonian Macedonian Greek or Greek Macedonian may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Macedonia (Greece), a region in Greece

*Macedonians (Greeks), the Greek people of Macedonia

* Greeks in North Macedonia, those living as a minority in the neighbo ...

population as part of their struggle for the resurrection of Greek statehood. According to the ''Istituto Geografiko de Agostini'' of Rome, in 1903 in the vilayet

A vilayet ( ota, , "province"), also known by #Names, various other names, was a first-order administrative division of the later Ottoman Empire. It was introduced in the Vilayet Law of 21 January 1867, part of the Tanzimat reform movement init ...

s of Selanik and Monastir Greek was the dominant language of instruction in the region:

The independence of the Greek kingdom, however, dealt a nearly fatal blow to the Hellenic idea in Macedonia. The flight of the Macedonian intelligentsia to independent Greece and the mass closures of Greek schools by the Ottoman authorities weakened the Hellenic presence in the region for a century ahead, until the incorporation of historical Macedonia into Greece following the Balkan Wars in 1913.

Bulgarian idea

Most of the population of Macedonia was described as Bulgarians during 16th and 17th centuries by Ottoman historians and travellers such as

Most of the population of Macedonia was described as Bulgarians during 16th and 17th centuries by Ottoman historians and travellers such as Hoca Sadeddin Efendi

Hoca Sadeddin Efendi ( ota, خواجه سعد الدین افندی; 1536/1537 – October 2, 1599İsmail Hâmi Danişmend, ''Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı'', Türkiye Yayınevi, İstanbul, 1971, p. 118. ) was an Ottoman scholar, official, and histor ...

, Mustafa Selaniki

Mustafa Selaniki ( tr, Selanıkî Mustafa; "Mustafa of Salonica; died 1600), also known as Selanıkî Mustafa Efendi, was an Ottoman scholar and chronicler, whose ''Tarih-i Selâniki'' described the Ottoman Empire of 1563–1599.

See also

*Salo ...

, Hadji Khalfa

Hadji (also spelled ''Hajji'', ''Haji'' or ''Hatzi'') is a title and prefix that is awarded to a person who has successfully completed the Hajj ("pilgrimage") to Mecca.

It may refer to: People

* El Hadji Diouf (born 1981), Senegalese footballer

* ...

and Evliya Çelebi

Derviş Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi ( ota, اوليا چلبى), was an Ottoman explorer who travelled through the territory of the Ottoman Empire and neighboring lands over a period of forty years, recording ...

. The name meant, however, rather little in view of the political oppression by the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

and the religious and cultural one by the Greek clergy. The Bulgarian language was preserved as a cultural medium only in a handful of monasteries, and to rise in terms of social status for the ordinary Bulgarian usually meant undergoing a process of Hellenisation

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the ...

. The Slavonic liturgy was, however, preserved at the lower levels of the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

The Archbishopric of Ohrid, also known as the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid

*T. Kamusella in The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe, Springer, 2008, p. 276

*Aisling Lyon, Decentralisation and the Management of Ethni ...

for several centuries until its abolition in 1767.

The creator of modern Bulgarian historiography, Petar Bogdan Bakshev

Petar Bogdan Bakshev or Petar Bogdan ( bg, Петър Богдан Бакшев); (Chiprovtsi, Ottoman Empire, 1601 – 1674) was an archbishop of the Roman Catholic Church in Bulgaria, historian and a key Bulgarian National Revival figure. Pet ...

in his first work "''Description of the Bulgarian Kingdom''" in 1640, mentioned the geographical and ethnic borders of Bulgaria and Bulgarian people including also "''the greather part of Macedonia ... as far as Ohrid, up to the boundaries of Albania and Greece ...''". Hristofor Zhefarovich

Christopher is the English version of a Europe-wide name derived from the Greek name Χριστόφορος (''Christophoros'' or '' Christoforos''). The constituent parts are Χριστός (''Christós''), "Christ" or "Anointed", and φέρει� ...

, a Macedonia-born 18th-century painter, had a crucial influence on the Bulgarian National Revival

The Bulgarian National Revival ( bg, Българско национално възраждане, ''Balgarsko natsionalno vazrazhdane'' or simply: Възраждане, ''Vazrazhdane'', and tr, Bulgar ulus canlanması) sometimes called the Bu ...

and significantly affected the entire Bulgarian heraldry

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, rank and pedigree. Armory, the best-known branch ...

of the 19th century, when it became most influential among all generations of Bulgarian enlighteners and revolutionaries and shaped the idea for a modern Bulgarian national symbol. In his testament, he explicitly noted that his relatives were "of Bulgarian nationality" and from Dojran

Dojran ( mk, Дојран ) was a city on the west shore of Lake Dojran in the southeast part of North Macedonia. Today, it is a collective name for two villages on the territory of the ruined city: Nov Dojran (New Dojran, settled from the end o ...

.

Although the first literary work in Modern Bulgarian, History of Slav-Bulgarians was written by a Macedonia born Bulgarian monk, Paisius of Hilendar

Saint Paisius of Hilendar or Paìsiy Hilendàrski ( bg, Свети Паисий Хилендарски) (1722–1773) was a Bulgarians, Bulgarian clergyman and a key Bulgarian National Revival figure. He is most famous for being the author of ''Is ...

as early as 1762, it took almost a century for the Bulgarian idea to regain ascendancy in the region. The Bulgarian advance in Macedonia in the 19th century was aided by the numerical superiority of the Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely understo ...

after the decrease in the Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

population, as well as by their improved economic status. The Bulgarians of Macedonia took active part in the struggle for independent Bulgarian Patriarchate

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church ( bg, Българска православна църква, translit=Balgarska pravoslavna tsarkva), legally the Patriarchate of Bulgaria ( bg, Българска патриаршия, links=no, translit=Balgarsk ...

and Bulgarian schools.

The representatives of the intelligentsia wrote in a language which they called Bulgarian and strove for a more even representation of the local Bulgarian dialects spoken in Macedonia in formal Bulgarian. The autonomous Bulgarian Exarchate

The Bulgarian Exarchate ( bg, Българска екзархия, Balgarska ekzarhiya; tr, Bulgar Eksarhlığı) was the official name of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church before its autocephaly was recognized by the Ecumenical See in 1945 and th ...

established in 1870 included northwestern Macedonia. After the overwhelming vote of the districts of Ohrid

Ohrid ( mk, Охрид ) is a city in North Macedonia and is the seat of the Ohrid Municipality. It is the largest city on Lake Ohrid and the List of cities in North Macedonia, eighth-largest city in the country, with the municipality recording ...

and Skopje

Skopje ( , , ; mk, Скопје ; sq, Shkup) is the capital and largest city of North Macedonia. It is the country's political, cultural, economic, and academic centre.

The territory of Skopje has been inhabited since at least 4000 BC; r ...

, it grew to include the whole of present-day Vardar

The Vardar (; mk, , , ) or Axios () is the longest river in North Macedonia and the second longest river in Greece, in which it reaches the Aegean Sea at Thessaloniki. It is long, out of which are in Greece, and drains an area of around . Th ...

and Pirin Macedonia

Pirin Macedonia or Bulgarian Macedonia ( bg, Пиринска Македония; Българска Македония) (''Pirinska Makedoniya or Bulgarska Makedoniya'') is the third-biggest part of the geographical region Macedonia located on t ...

in 1874. This process of Bulgarian national revival

The Bulgarian National Revival ( bg, Българско национално възраждане, ''Balgarsko natsionalno vazrazhdane'' or simply: Възраждане, ''Vazrazhdane'', and tr, Bulgar ulus canlanması) sometimes called the Bu ...

in Macedonia, however, was much less successful in historical Macedonia, which beside Slavs had compact Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Aromanian populations. The Hellenic idea and the Patriarchate of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople ( el, Οἰκουμενικὸν Πατριαρχεῖον Κωνσταντινουπόλεως, translit=Oikoumenikón Patriarkhíon Konstantinoupóleos, ; la, Patriarchatus Oecumenicus Constanti ...

preserved much of their earlier influence among local Bulgarians and the arrival of the Bulgarian idea turned the region into a battlefield between those owing allegiance to the Patriarchate and tose to Exarchate with division lines often separating family and kin.

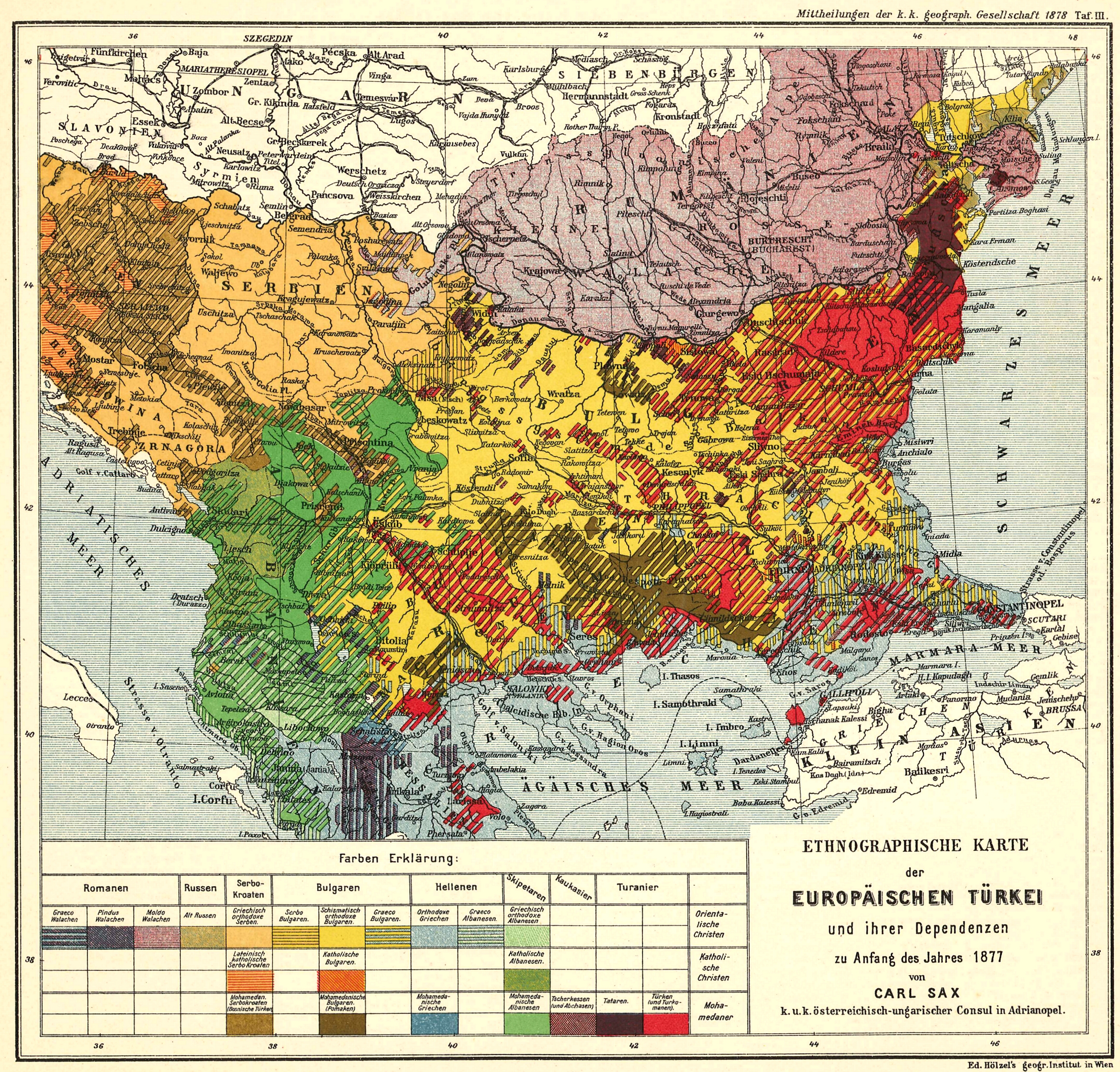

European ethnographs and linguists until the

European ethnographs and linguists until the Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

usually regarded the language of the Slavic population of Macedonia as Bulgarian

Bulgarian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Bulgaria

* Bulgarians, a South Slavic ethnic group

* Bulgarian language, a Slavic language

* Bulgarian alphabet

* A citizen of Bulgaria, see Demographics of Bulgaria

* Bul ...

. French scholars Ami Boué

Ami Boué (16 March 179421 November 1881) was a geologist of French Huguenot origin. Born at Hamburg he trained in Edinburgh and across Europe. He travelled across Europe, studying geology, as well as ethnology, and is considered to be among th ...

in 1840 and Guillaume Lejean in 1861, Germans August Grisebach

August Heinrich Rudolf Grisebach () was a German botany, botanist and phytogeography, phytogeographer. He was born in Hannover on 17 April 1814 and died in Göttingen on 9 May 1879.

Biography

Grisebach studied at the Lyceum in Hanover, the clo ...

in 1841, J. Hahn in 1858 and 1863, August Heinrich Petermann

Augustus Heinrich Petermann (18 April 182225 September 1878) was a German cartographer.

Early years

Petermann was born in Bleicherode, Germany. When he was 14 years old he started grammar school in the nearby town of Nordhausen. His mother wa ...

in 1869 and Heinrich Kiepert

Heinrich Kiepert (July 31, 1818 – April 21, 1899) was a German geographer.

Early life and education

Kiepert was born in Berlin. He traveled frequently as a youth with his family and documented his travels by drawing. His family was friends wit ...

in 1876, Slovak Pavel Jozef Šafárik

Pavel Jozef Šafárik ( sk, Pavol Jozef Šafárik; 13 May 1795 – 26 June 1861) was an ethnic Slovak philologist, poet, literary historian, historian and ethnographer in the Kingdom of Hungary. He was one of the first scientific Slavists.

Famil ...

in 1842 and the Czechs Karel Jaromír Erben

Karel Jaromír Erben (; 7 November 1811 – 21 November 1870) was a Czech folklorist

Folklore studies, less often known as folkloristics, and occasionally tradition studies or folk life studies in the United Kingdom, is the branch of anthropol ...

in 1868 and F. Brodaska in 1869, Englishmen James Wyld in 1877 and Georgina Muir Mackenzie and Adeline Paulina Irby in 1863, Serbians Davidovitch in 1848, Constant Desjardins in 1853 and Stjepan Verković in 1860, Russians Victor Grigorovich

Victor Ivanovich Grigorovich (russian: link=no, Ви́ктор Ива́нович Григоро́вич; 30 April 1815 – 19 December 1876) was a Russian Slavist, folklorist, literary critic, historian and journalist, one of the originators of ...

in 1848 Vikentij Makušev and Mikhail Mirkovich

Mikhail Fyodorovich Mirkovich (September 17, 1836 – March 24, 1891) was an Imperial Russian regimental commander and ethnographer. He participated in the wars in Poland and against the Ottoman Empire. He is the son of Fedor Yakovlevich Mirkovich. ...

in 1867, as well as Austrian Karl Sax in 1878 published ethnography or linguistic books, or travel notes, which defined the Slavic population of Macedonia as Bulgarian. Austrian doctor Josef Müller published travel notes in 1844 in which he regarded the Slavic population of Macedonia as Serbian. The region was further identified as predominantly Greek by French F. Bianconi in 1877 and by Englishman Edward Stanford

Edward Stanford (27 May 1827 3 November 1904) was the founder of Stanfords, now a pair of map and book shops based in London and Bristol, UK.

Biography

Born in 1827, and educated at the City of London School, Edward Stanford developed his i ...

in 1877. He maintained that the urban population of Macedonia was entirely Greek, whereas the peasantry was of mixed, Bulgarian-Greek origin and had Greek consciousness but had not yet mastered the Greek language.

Macedonian question

In Europe, the classic non-national states were the ''multi-ethnic empires'' such as the Ottoman Empire, ruled by a

In Europe, the classic non-national states were the ''multi-ethnic empires'' such as the Ottoman Empire, ruled by a Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

and the population belonged to many ethnic groups, which spoke many languages. The idea of nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

was an increasing emphasis during the 19th century, on the ethnic

An ethnic group or an ethnicity is a grouping of people who identify with each other on the basis of shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. Those attributes can include common sets of traditions, ancestry, language, history, ...

and racial

A race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 1500s, when it was used to refer to groups of variou ...

origins of the nations. The most noticeable characteristic was the degree to which nation-states use the state as an instrument of ''national unity'', in economic, social and cultural life. By the 19th century, the Ottomans had fallen well behind the rest of Europe in science, technology, and industry. By that time Bulgarians had initiated a purposeful struggle against the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

clerics. Bulgarian religious leaders had realised that any further struggle for the rights of the Bulgarians

Bulgarians ( bg, българи, Bǎlgari, ) are a nation and South Slavic ethnic group native to Bulgaria and the rest of Southeast Europe.

Etymology

Bulgarians derive their ethnonym from the Bulgars. Their name is not completely understo ...

in the Ottoman Empire could not succeed unless they managed to obtain at least some degree of autonomy from the Patriarchate of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople ( el, Οἰκουμενικὸν Πατριαρχεῖον Κωνσταντινουπόλεως, translit=Oikoumenikón Patriarkhíon Konstantinoupóleos, ; la, Patriarchatus Oecumenicus Constanti ...

. The foundation of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870, which included most of Macedonia by a firman

A firman ( fa, , translit=farmân; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods they were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The word firman com ...

of Sultan Abdülaziz

Abdulaziz ( ota, عبد العزيز, ʿAbdü'l-ʿAzîz; tr, Abdülaziz; 8 February 18304 June 1876) was the 32nd List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and reigned from 25 June 1861 to 30 May 1876, when he was 187 ...

was the direct result of the struggle of the Bulgarian Orthodox against the domination of the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople ( el, Οἰκουμενικὸν Πατριαρχεῖον Κωνσταντινουπόλεως, translit=Oikoumenikón Patriarkhíon Konstantinoupóleos, ; la, Patriarchatus Oecumenicus Constanti ...

in the 1850s and 1860s.

Afterward, in 1876 the Bulgarians revolted in the ''April uprising

The April Uprising ( bg, Априлско въстание, Aprilsko vastanie) was an insurrection organised by the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire from April to May 1876. The regular Ottoman Army and irregular bashi-bazouk units brutally su ...

''. The emergence of Bulgarian national sentiments was closely related to the re-establishment of the independent Bulgarian church. This rise of national awareness became known as the Bulgarian National Revival

The Bulgarian National Revival ( bg, Българско национално възраждане, ''Balgarsko natsionalno vazrazhdane'' or simply: Възраждане, ''Vazrazhdane'', and tr, Bulgar ulus canlanması) sometimes called the Bu ...

. However, the uprising was crushed by the Ottomans. As a result, on the Constantinople Conference

The 1876–77 Constantinople Conference ( tr, Tersane Konferansı "Shipyard Conference", after the venue ''Tersane Sarayı'' "Shipyard Palace") of the Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Russia) was held in Constan ...

in 1876 the predominant Bulgarian character of the Slavs in Macedonia reflected in the borders of future autonomous Bulgaria as it was drawn there. The Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

eventually gave their consent to variant, which excluded historical Macedonia and Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

, and denied Bulgaria access to the Aegean sea

The Aegean Sea ; tr, Ege Denizi (Greek language, Greek: Αιγαίο Πέλαγος: "Egéo Pélagos", Turkish language, Turkish: "Ege Denizi" or "Adalar Denizi") is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It ...

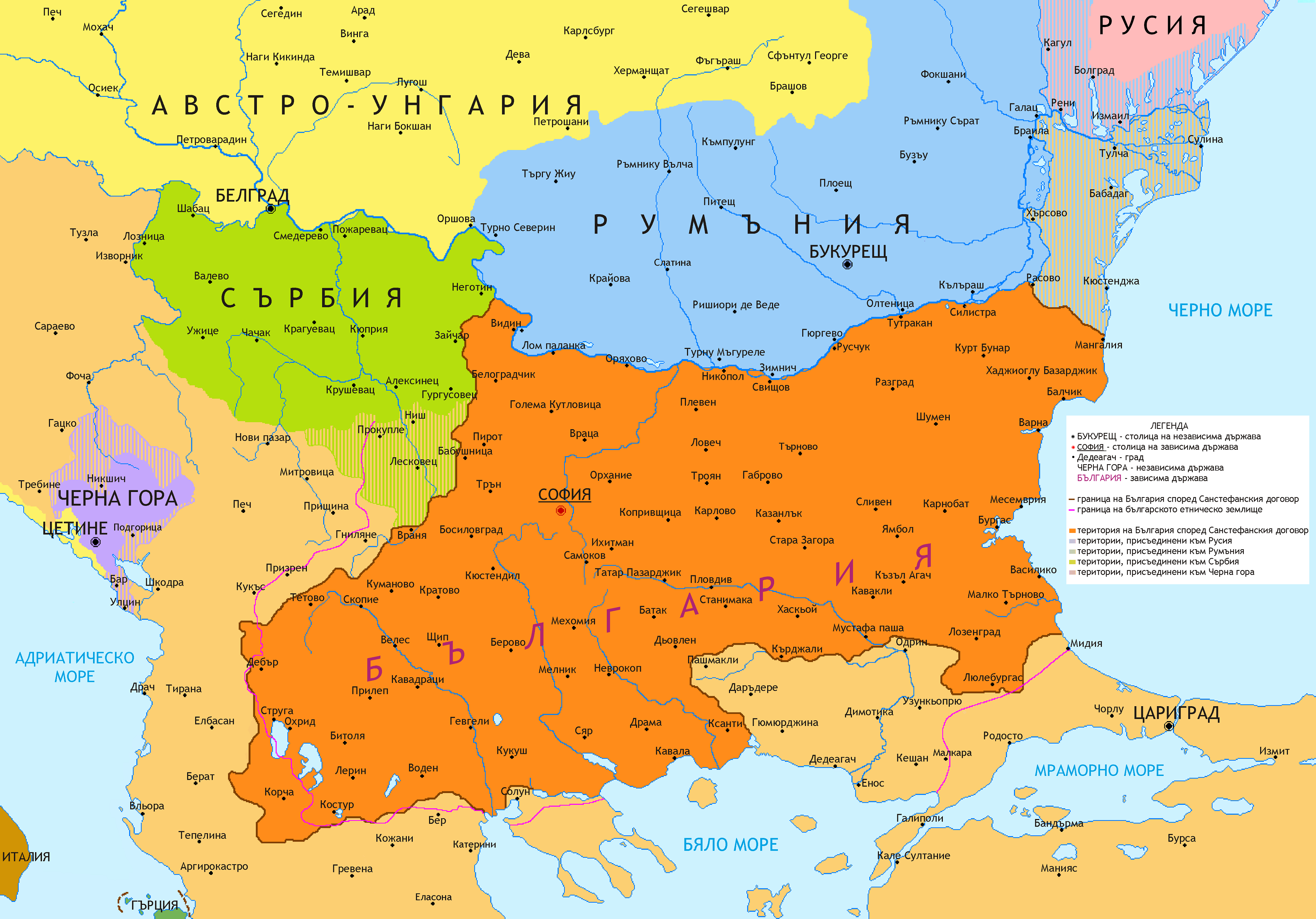

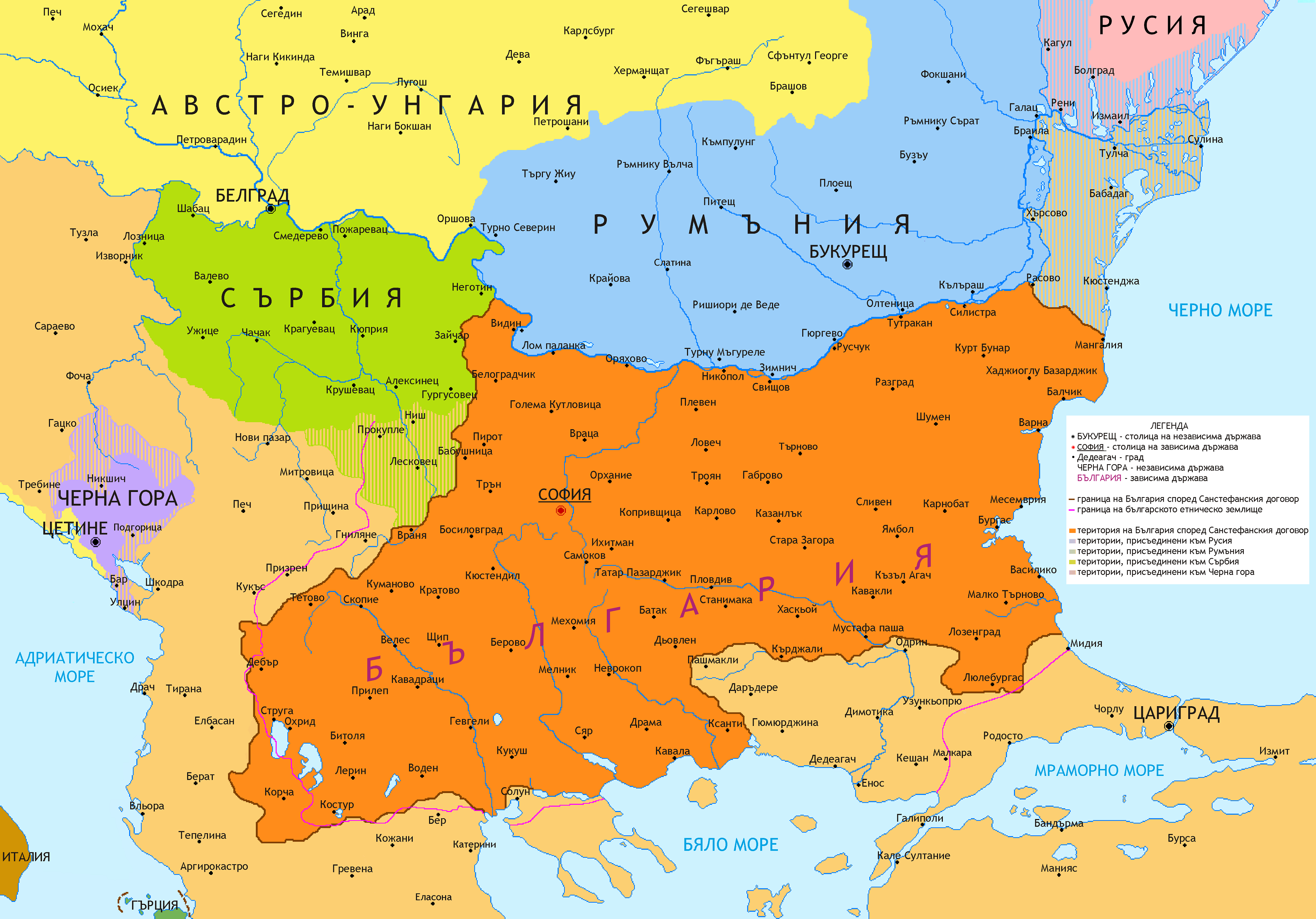

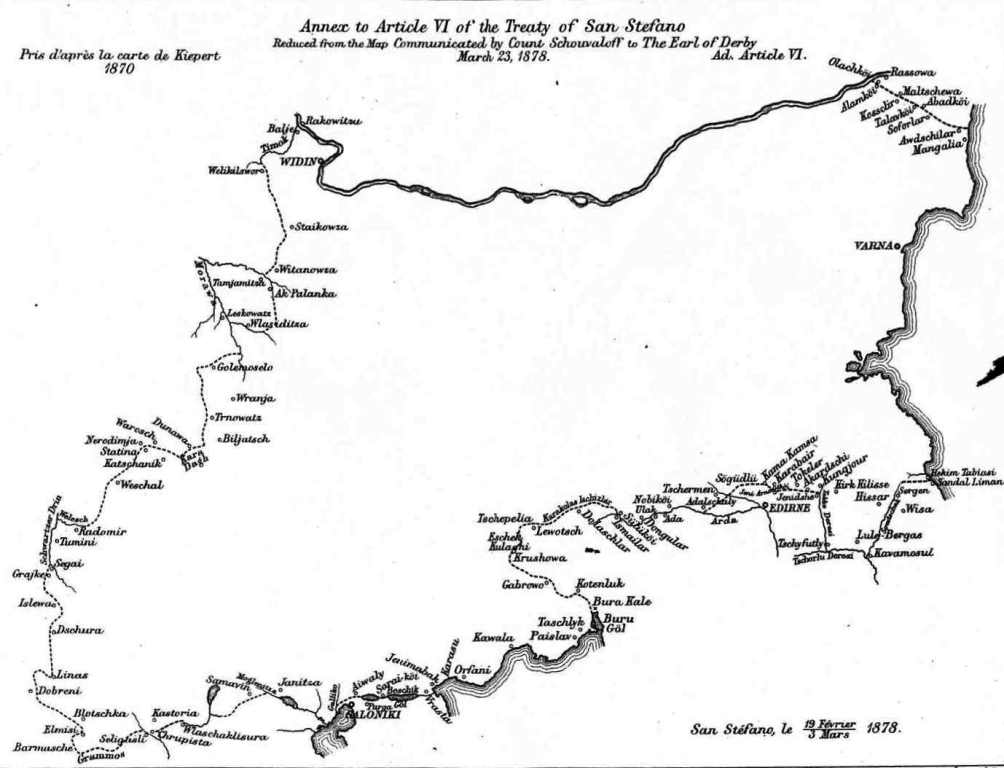

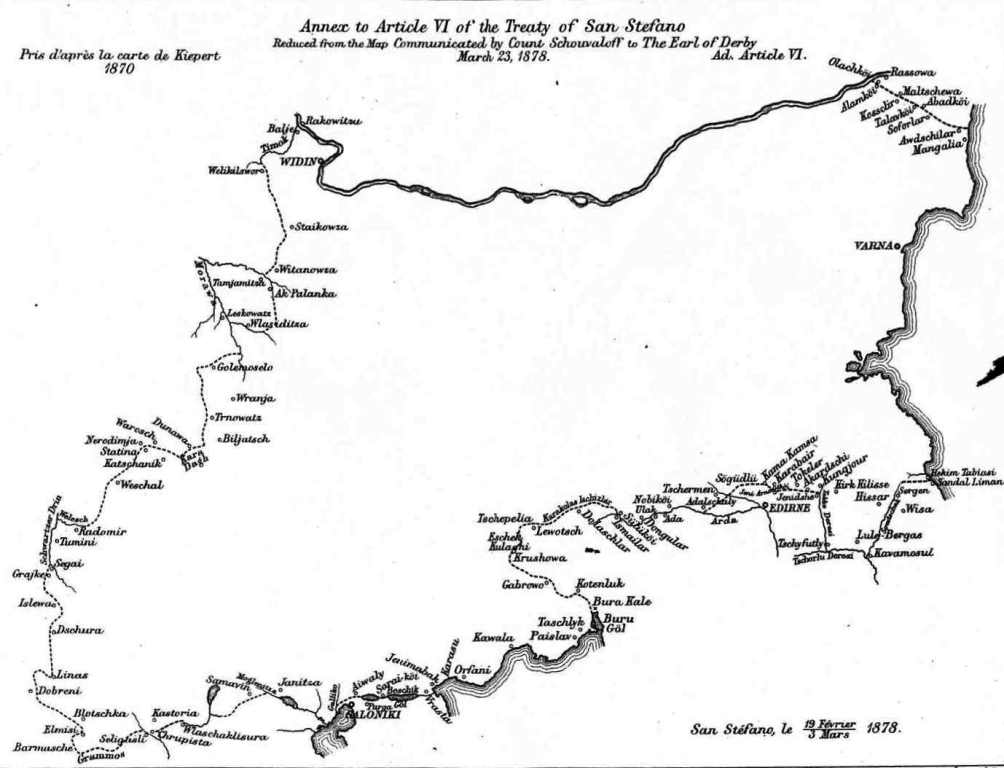

, but otherwise incorporated all other regions in the Ottoman Empire inhabited by Bulgarians. At the last minute, however, the Ottomans rejected the plan with the secret support of Britain. Having its reputation at stake, Russia had no other choice but to declare war on the Ottomans in April 1877. The Treaty of San Stefano

The 1878 Treaty of San Stefano (russian: Сан-Стефанский мир; Peace of San-Stefano, ; Peace treaty of San-Stefano, or ) was a treaty between the Russian and Ottoman empires at the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-187 ...

from 1878, which reflected the maximum desired by Russian expansionist policy, gave Bulgaria the whole of Macedonia except Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

, the Chalcidice

Chalkidiki (; el, Χαλκιδική , also spelled Halkidiki, is a peninsula and regional unit of Greece, part of the region of Central Macedonia, in the geographic region of Macedonia in Northern Greece. The autonomous Mount Athos region c ...

peninsula and the valley of the Aliakmon

The Haliacmon ( el, Αλιάκμονας, ''Aliákmonas''; formerly: , ''Aliákmon'' or ''Haliákmōn'') is the longest river flowing entirely in Greece, with a total length of . In Greece there are three rivers longer than Haliakmon, Maritsa ( el ...

.

The

The Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

in the same year redistributed most Bulgarian territories that the previous treaty had given to the Principality of Bulgaria

The Principality of Bulgaria ( bg, Княжество България, Knyazhestvo Balgariya) was a vassal state under the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire. It was established by the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

After the Russo-Turkish War ende ...

back to the Ottoman Empire. This included the whole of Macedonia. As a result, in late 1878, the Kresna–Razlog uprising

The Kresna–Razlog Uprising ( bg, Кресненско-Разложко въстание, ''Kresnensko-Razlozhko vastanie''; mk, Кресненско востание, ''Kresnensko vоstanie'', Kresna Uprising) named by the insurgents the Maced ...

– an unsuccessful Bulgarian revolt against the Ottoman rule in the region of Macedonia – broke out. However the decision taken at the Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878) was a diplomatic conference to reorganise the states in the Balkan Peninsula after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, which had been won by Russia against the Ottoman Empire. Represented at th ...

soon turned the Macedonian question into "the apple of constant discord" between Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria. The Bulgarian national revival