MHF on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marburg virus disease (MVD; formerly Marburg hemorrhagic fever) is a

MVD is clinically indistinguishable from Ebola virus disease (EVD), and it can also easily be confused with many other diseases prevalent in Equatorial Africa, such as other

MVD is clinically indistinguishable from Ebola virus disease (EVD), and it can also easily be confused with many other diseases prevalent in Equatorial Africa, such as other

In October 2017 an outbreak of Marburg virus disease was detected in Kween District, Eastern Uganda. All three initial cases (belonging to one family – two brothers and one sister) had died by 3 November. The fourth case – a health care worker – developed symptoms on 4 November and was admitted to a hospital. The first confirmed case traveled to Kenya before the death. A close contact of the second confirmed case traveled to Kampala. It is reported that several hundred people may have been exposed to infection.

In October 2017 an outbreak of Marburg virus disease was detected in Kween District, Eastern Uganda. All three initial cases (belonging to one family – two brothers and one sister) had died by 3 November. The fourth case – a health care worker – developed symptoms on 4 November and was admitted to a hospital. The first confirmed case traveled to Kenya before the death. A close contact of the second confirmed case traveled to Kampala. It is reported that several hundred people may have been exposed to infection.

ViralZone: Marburg virus

* Centers for Disease Control,

Infection Control for Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers In the African Health Care Setting

'. * Center for Disease Control,

'. * Center for Disease Control,

' * * World Health Organization,

Marburg Haemorrhagic Fever

'.

Red Cross PDF

Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Filoviridae

{{Zoonotic viral diseases Animal viral diseases Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers Biological weapons Hemorrhagic fevers Tropical diseases Virus-related cutaneous conditions Zoonoses Marburgviruses

viral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses in which fever and hemorrhage are caused by a viral infection. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families ''Filoviridae'', ''Flavi ...

in humans and primates caused by either of the two Marburgvirus

The genus ''Marburgvirus'' is the taxonomic home of ''Marburg marburgvirus'', whose members are the two known marburgviruses, Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV). Both viruses cause Marburg virus disease in humans and nonhuman primate ...

es: Marburg virus

Marburg virus (MARV) is a hemorrhagic fever virus of the ''Filoviridae'' family of viruses and a member of the species '' Marburg marburgvirus'', genus ''Marburgvirus''. It causes Marburg virus disease in primates, a form of viral hemorrhagic f ...

(MARV) and Ravn virus

Ravn virus (; RAVV) is a close relative of Marburg virus (MARV). RAVV causes Marburg virus disease in humans and nonhuman primates, a form of viral hemorrhagic fever. RAVV is a Select agent, World Health Organization Risk Group 4 Pathogen (requi ...

(RAVV). Its clinical symptoms are very similar to those of Ebola virus disease

Ebola, also known as Ebola virus disease (EVD) and Ebola hemorrhagic fever (EHF), is a viral hemorrhagic fever in humans and other primates, caused by ebolaviruses. Symptoms typically start anywhere between two days and three weeks after becom ...

(EVD).

Egyptian fruit bats are believed to be the normal carrier in nature and Marburg virus RNA has been isolated from them.

Signs and symptoms

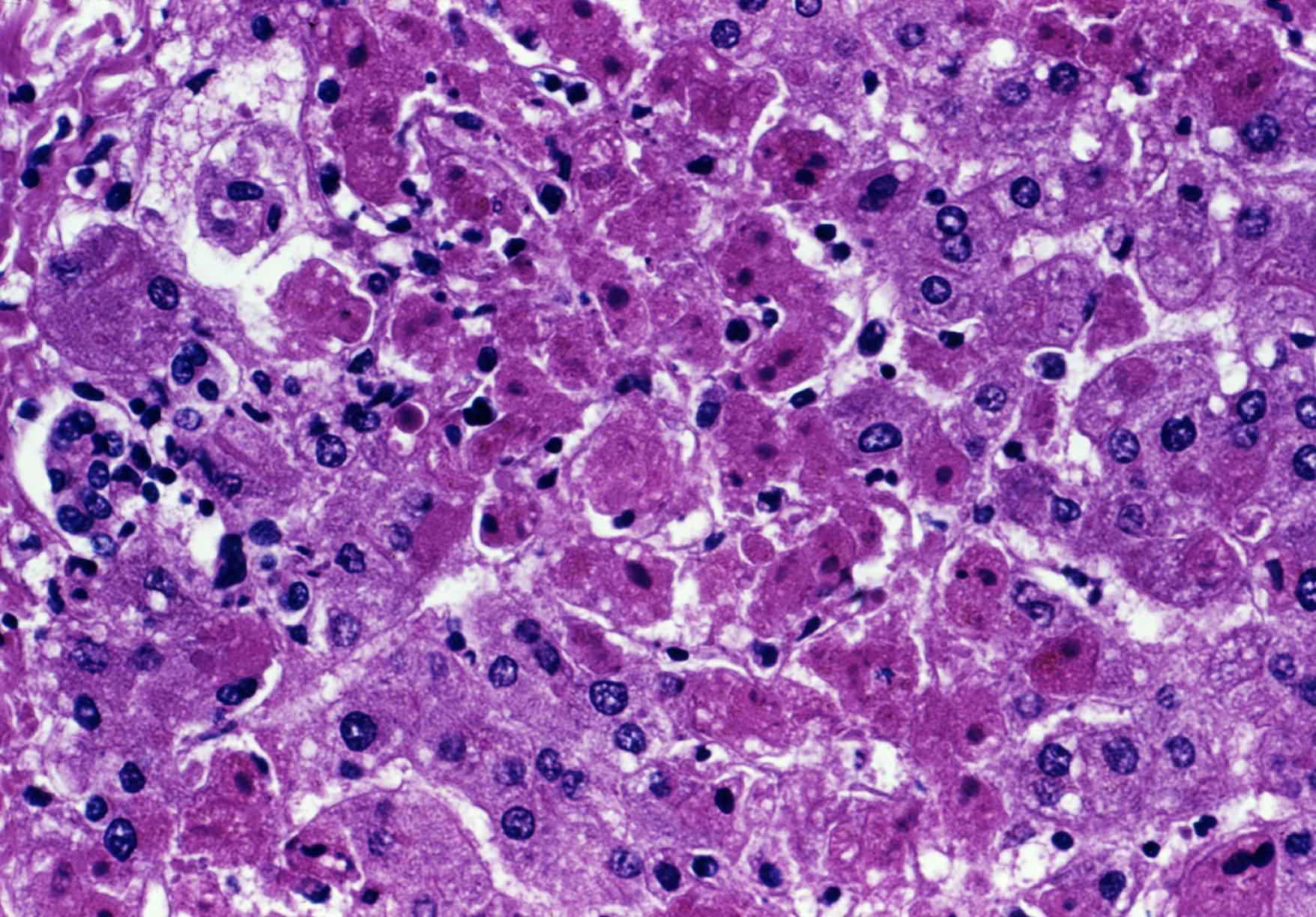

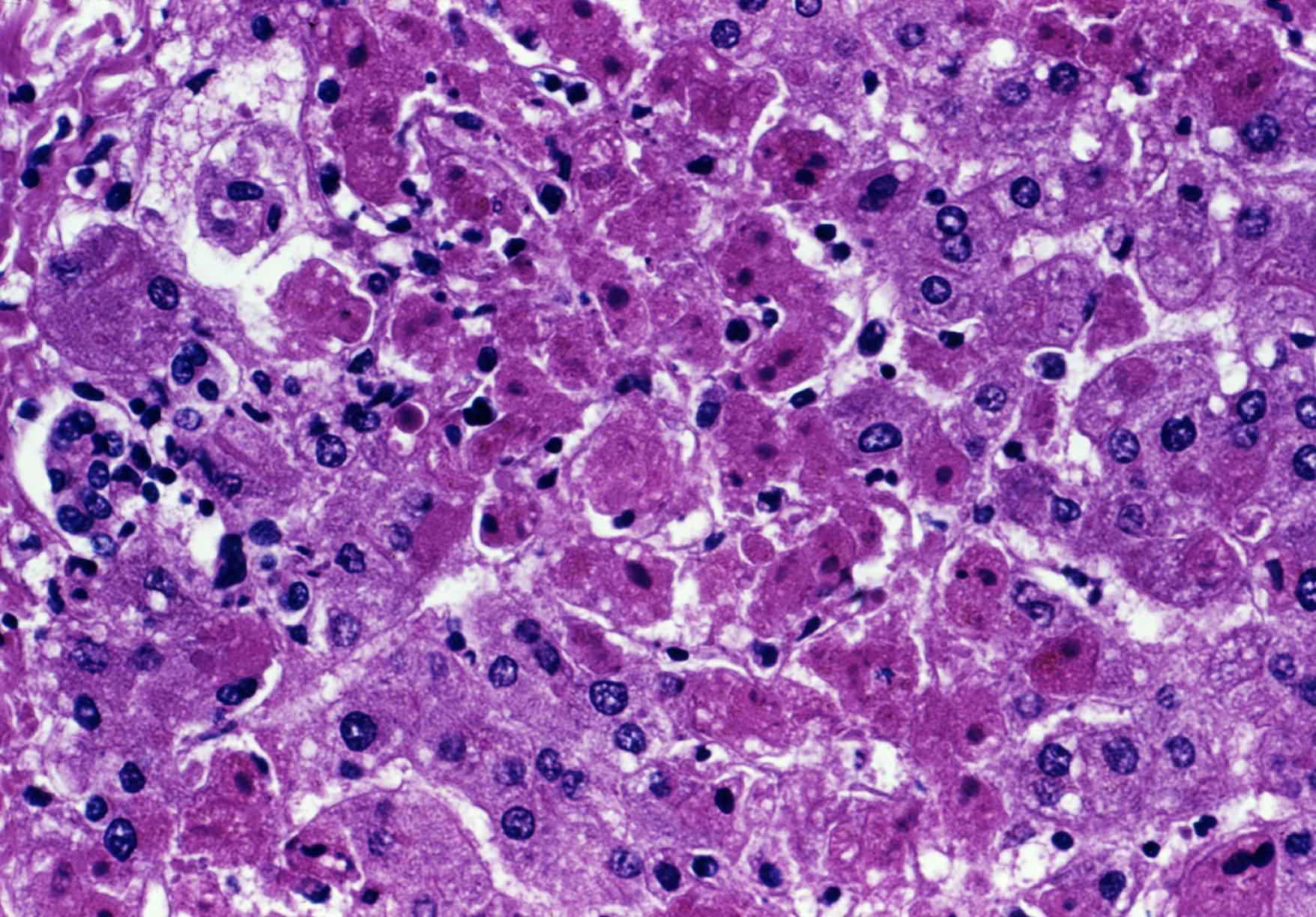

The most detailed study on the frequency, onset, and duration of MVDclinical signs

Signs and symptoms are the observed or detectable signs, and experienced symptoms of an illness, injury, or condition. A sign for example may be a higher or lower temperature than normal, raised or lowered blood pressure or an abnormality showin ...

and symptom

Signs and symptoms are the observed or detectable signs, and experienced symptoms of an illness, injury, or condition. A sign for example may be a higher or lower temperature than normal, raised or lowered blood pressure or an abnormality showin ...

s was performed during the 1998–2000 mixed MARV/RAVV disease outbreak. A maculopapular rash, petechia

A petechia () is a small red or purple spot (≤4 mm in diameter) that can appear on the skin, conjunctiva, retina, and Mucous membrane, mucous membranes which is caused by haemorrhage of capillaries. The word is derived from Italian , 'freckle,' ...

e, purpura, ecchymoses, and hematoma

A hematoma, also spelled haematoma, or blood suffusion is a localized bleeding outside of blood vessels, due to either disease or trauma including injury or surgery and may involve blood continuing to seep from broken capillary, capillaries. A he ...

s (especially around needle injection sites) are typical hemorrhagic manifestations. However, contrary to popular belief, hemorrhage does not lead to hypovolemia

Hypovolemia, also known as volume depletion or volume contraction, is a state of abnormally low extracellular fluid in the body. This may be due to either a loss of both salt and water or a decrease in blood volume. Hypovolemia refers to the los ...

and is not the cause of death (total blood loss is minimal except during labor). Instead, death occurs due to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) due to fluid redistribution, hypotension, disseminated intravascular coagulation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a condition in which blood clots form throughout the body, blocking small blood vessels. Symptoms may include chest pain, shortness of breath, leg pain, problems speaking, or problems moving parts o ...

, and focal tissue necroses.

Clinical phases of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever's presentation are described below. Note that phases overlap due to variability between cases.

# Incubation: 2–21 days, averaging 5–9 days.

# Generalization Phase: Day 1 up to Day 5 from the onset of clinical symptoms. MHF presents with a high fever 104 °F (~40˚C) and a sudden, severe headache, with accompanying chills, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, pharyngitis, maculopapular rash, abdominal pain, conjunctivitis, and malaise.

# Early Organ Phase: Day 5 up to Day 13. Symptoms include prostration, dyspnea, edema

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's Tissue (biology), tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels t ...

, conjunctival injection, viral exanthema

An exanthem is a widespread rash occurring on the outside of the body and usually occurring in children. An exanthem can be caused by toxins, drugs, or microorganisms, or can result from autoimmune disease.

The term exanthem is from the Greek ...

, and CNS symptoms, including encephalitis, confusion, delirium, apathy, and aggression. Hemorrhagic symptoms typically occur late and herald the end of the early organ phase, leading either to eventual recovery or worsening and death. Symptoms include bloody stools, ecchymoses, blood leakage from venipuncture sites, mucosal and visceral hemorrhaging, and possibly hematemesis.

# Late Organ Phase: Day 13 up to Day 21+. Symptoms bifurcate into two constellations for survivors and fatal cases. Survivors will enter a convalescence phase, experiencing myalgia

Myalgia (also called muscle pain and muscle ache in layman's terms) is the medical term for muscle pain. Myalgia is a symptom of many diseases. The most common cause of acute myalgia is the overuse of a muscle or group of muscles; another likel ...

, fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a medical condition defined by the presence of chronic widespread pain, fatigue, waking unrefreshed, cognitive symptoms, lower abdominal pain or cramps, and depression. Other symptoms include insomnia and a general hyp ...

, hepatitis, asthenia, ocular symptoms, and psychosis. Fatal cases continue to deteriorate, experiencing continued fever, obtundation, coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

, convulsions, diffuse coagulopathy

Coagulopathy (also called a bleeding disorder) is a condition in which the blood's ability to coagulate (form clots) is impaired. This condition can cause a tendency toward prolonged or excessive bleeding (bleeding diathesis), which may occur spo ...

, metabolic disturbances, shock and death, with death typically occurring between days 8 and 16.

Causes

MVD is caused by two viruses; Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV), family Filoviridae. Marburgviruses are endemic in arid woodlands of equatorial Africa. Most marburgvirus infections were repeatedly associated with people visiting natural caves or working in mines. In 2009, the successful isolation of infectious MARV and RAVV was reported from healthy Egyptian fruit bat caught in caves. This isolation strongly suggests thatOld World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

fruit bats are involved in the natural maintenance of marburgviruses and that visiting bat-infested caves is a risk factor for acquiring marburgvirus infections. Further studies are necessary to establish whether Egyptian rousettes are the actual hosts of MARV and RAVV or whether they get infected via contact with another animal and therefore serve only as intermediate hosts. Another risk factor is contact with nonhuman primates, although only one outbreak of MVD (in 1967) was due to contact with infected monkeys.

Contrary to Ebola virus disease (EVD), which has been associated with heavy rains after long periods of dry weather, triggering factors for spillover of marburgviruses into the human population have not yet been described.

Diagnosis

MVD is clinically indistinguishable from Ebola virus disease (EVD), and it can also easily be confused with many other diseases prevalent in Equatorial Africa, such as other

MVD is clinically indistinguishable from Ebola virus disease (EVD), and it can also easily be confused with many other diseases prevalent in Equatorial Africa, such as other viral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses in which fever and hemorrhage are caused by a viral infection. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families ''Filoviridae'', ''Flavi ...

s, falciparum malaria, typhoid fever, shigellosis

Shigellosis is an infection of the intestines caused by ''Shigella'' bacteria. Symptoms generally start one to two days after exposure and include diarrhea, fever, abdominal pain, and feeling the need to pass stools even when the bowels are emp ...

, rickettsial diseases such as typhus, cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, gram-negative sepsis, borreliosis

Lyme disease, also known as Lyme borreliosis, is a vector-borne disease caused by the ''Borrelia'' bacterium, which is spread by ticks in the genus ''Ixodes''. The most common sign of infection is an expanding red rash, known as erythema migran ...

such as relapsing fever or EHEC enteritis. Other infectious diseases that ought to be included in the differential diagnosis

In healthcare, a differential diagnosis (abbreviated DDx) is a method of analysis of a patient's history and physical examination to arrive at the correct diagnosis. It involves distinguishing a particular disease or condition from others that p ...

include leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a blood infection caused by the bacteria ''Leptospira''. Signs and symptoms can range from none to mild (headaches, muscle pains, and fevers) to severe ( bleeding in the lungs or meningitis). Weil's disease, the acute, severe ...

, scrub typhus, plague

Plague or The Plague may refer to:

Agriculture, fauna, and medicine

*Plague (disease), a disease caused by ''Yersinia pestis''

* An epidemic of infectious disease (medical or agricultural)

* A pandemic caused by such a disease

* A swarm of pes ...

, Q fever, candidiasis, histoplasmosis, trypanosomiasis, visceral

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a wide array of clinical manifestations caused by parasites of the trypanosome genus ''Leishmania''. It is generally spread through the bite of phlebotomine sandflies, ''Phlebotomus'' and ''Lutzomyia'', and occurs most freq ...

, hemorrhagic smallpox, measles

Measles is a highly contagious infectious disease caused by measles virus. Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than , cough, ...

, and fulminant viral hepatitis. Non-infectious diseases that can be confused with MVD are acute promyelocytic leukemia

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML, APL) is a subtype of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a cancer of the white blood cells. In APL, there is an abnormal accumulation of immature granulocytes called promyelocytes. The disease is characterized by a ...

, hemolytic uremic syndrome, snake envenomation, clotting factor

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

deficiencies/platelet disorders, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia, Kawasaki disease, and even warfarin intoxication. The most important indicator that may lead to the suspicion of MVD at clinical examination is the medical history of the patient, in particular the travel and occupational history (which countries and caves were visited?) and the patient's exposure to wildlife (exposure to bats or bat excrements?). MVD can be confirmed by isolation of marburgviruses from or by detection of marburgvirus antigen or genomic or subgenomic RNAs in patient blood or serum

Serum may refer to:

*Serum (blood), plasma from which the clotting proteins have been removed

**Antiserum, blood serum with specific antibodies for passive immunity

* Serous fluid, any clear bodily fluid

* Truth serum, a drug that is likely to mak ...

samples during the acute phase of MVD. Marburgvirus isolation is usually performed by inoculation

Inoculation is the act of implanting a pathogen or other microorganism. It may refer to methods of artificially inducing immunity against various infectious diseases, or it may be used to describe the spreading of disease, as in "self-inoculati ...

of grivet

The grivet (''Chlorocebus aethiops'') is an Old World monkey with long white tufts of hair along the sides of its face. Some authorities consider this and all of the members of the genus ''Chlorocebus'' to be a single species, ''Cercopithecus ae ...

kidney epithelial Vero E6 or MA-104 cell culture

Cell culture or tissue culture is the process by which cells are grown under controlled conditions, generally outside of their natural environment. The term "tissue culture" was coined by American pathologist Montrose Thomas Burrows. This te ...

s or by inoculation of human adrenal carcinoma SW-13 cells, all of which react to infection with characteristic cytopathic effect

Cytopathic effect or cytopathogenic effect (abbreviated CPE) refers to structural changes in host cells that are caused by viral invasion. The infecting virus causes lysis of the host cell or when the cell dies without lysis due to an inability to ...

s. Filovirions can easily be visualized and identified in cell culture by electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

due to their unique filamentous shapes, but electron microscopy cannot differentiate the various filoviruses alone despite some overall length differences. Immunofluorescence assays are used to confirm marburgvirus presence in cell cultures. During an outbreak, virus isolation and electron microscopy are most often not feasible options. The most common diagnostic methods are therefore RT-PCR in conjunction with antigen-capture ELISA, which can be performed in field or mobile hospitals and laboratories. Indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFAs) are not used for diagnosis of MVD in the field anymore.

Classification

Marburg virus disease (MVD) is the official name listed in the World Health Organization'sInternational Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is a globally used diagnostic tool for epidemiology, health management and clinical purposes. The ICD is maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO), which is the directing and coordinating ...

10 (ICD-10) for the human disease caused by any of the two marburgvirus

The genus ''Marburgvirus'' is the taxonomic home of ''Marburg marburgvirus'', whose members are the two known marburgviruses, Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV). Both viruses cause Marburg virus disease in humans and nonhuman primate ...

es Marburg virus

Marburg virus (MARV) is a hemorrhagic fever virus of the ''Filoviridae'' family of viruses and a member of the species '' Marburg marburgvirus'', genus ''Marburgvirus''. It causes Marburg virus disease in primates, a form of viral hemorrhagic f ...

(MARV) and Ravn virus

Ravn virus (; RAVV) is a close relative of Marburg virus (MARV). RAVV causes Marburg virus disease in humans and nonhuman primates, a form of viral hemorrhagic fever. RAVV is a Select agent, World Health Organization Risk Group 4 Pathogen (requi ...

(RAVV). In the scientific literature, Marburg hemorrhagic fever (MHF) is often used as an unofficial alternative name for the same disease. Both disease names are derived from the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

city Marburg, where MARV was first discovered.

Transmission

The details of the initial transmission of MVD to humans remain incompletely understood. Transmission most likely occurs from Egyptian fruit bats or another natural host, such asnon-human primate

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including humans ...

s or through the consumption of bushmeat

Bushmeat is meat from wildlife species that are hunted for human consumption, most often referring to the meat of game in Africa. Bushmeat represents

a primary source of animal protein and a cash-earning commodity for inhabitants of humid tropi ...

, but the specific routes and body fluids involved are unknown. Human-to-human transmission of MVD occurs through direct contact with infected bodily fluids such as blood.

Prevention

There are currently no Food and Drug Administration-approved vaccines for the prevention of MVD. Many candidate vaccines have been developed and tested in various animal models. Of those, the most promising ones areDNA vaccines

A DNA vaccine is a type of vaccine that transfects a specific antigen-coding DNA sequence into the cells of an organism as a mechanism to induce an immune response.

DNA vaccines work by injecting genetically engineered plasmid containing the D ...

or based on Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus replicons, vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus (VSIV) or filovirus-like particles (VLPs) as all of these candidates could protect nonhuman primates from marburgvirus-induced disease. DNA vaccines have entered clinical trials. Marburgviruses are highly infectious, but not very contagious

Contagious may refer to:

* Contagious disease

Literature

* Contagious (magazine), a marketing publication

* ''Contagious'' (novel), a science fiction thriller novel by Scott Sigler

Music

Albums

*''Contagious'' (Peggy Scott-Adams album), 1997

* ...

. They do not get transmitted by aerosol

An aerosol is a suspension (chemistry), suspension of fine solid particles or liquid Drop (liquid), droplets in air or another gas. Aerosols can be natural or Human impact on the environment, anthropogenic. Examples of natural aerosols are fog o ...

during natural MVD outbreaks. Due to the absence of an approved vaccine, prevention of MVD therefore relies predominantly on quarantine of confirmed or high probability cases, proper personal protective equipment, and sterilization and disinfection.

Endemic zones

The natural maintenance hosts of marburg viruses remain to be identified unequivocally. However, the isolation of both MARV and RAVV from bats and the association of several MVD outbreaks with bat-infested mines or caves strongly suggests that bats are involved in marburg virus transmission to humans. Avoidance of contact with bats and abstaining from visits to caves is highly recommended, but may not be possible for those working in mines or people dependent on bats as a food source.During outbreaks

Since marburgviruses are not spread via aerosol, the most straightforward prevention method during MVD outbreaks is to avoid direct (skin-to-skin) contact with patients, their excretions and body fluids, and any possibly contaminated materials and utensils. Patients should be isolated, but still are safe to be visited by family members. Medical staff should be trained in and apply strict barrier nursing techniques (disposable face mask, gloves, goggles, and a gown at all times). Traditionalburial

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

rituals, especially those requiring embalming of bodies, should be discouraged or modified, ideally with the help of local traditional healers.

In the laboratory

Marburgviruses are World Health Organization Risk Group 4 Pathogens, requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment, laboratory researchers have to be properly trained in BSL-4 practices and wear proper personal protective equipment.Treatment

There is currently no effective marburgvirus-specific therapy for MVD. Treatment is primarily supportive in nature and includes minimizing invasive procedures, balancing fluids andelectrolyte

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon dis ...

s to counter dehydration, administration of anticoagulants early in infection to prevent or control disseminated intravascular coagulation

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a condition in which blood clots form throughout the body, blocking small blood vessels. Symptoms may include chest pain, shortness of breath, leg pain, problems speaking, or problems moving parts o ...

, administration of procoagulants late in infection to control hemorrhaging, maintaining oxygen levels, pain management, and administration of antibiotics or antifungals

An antifungal medication, also known as an antimycotic medication, is a pharmaceutical fungicide or fungistatic used to treat and prevent mycosis such as athlete's foot, ringworm, candidiasis (thrush), serious systemic infections such as crypto ...

to treat secondary infections.

Prognosis

Prognosis is generally poor. If a patient survives, recovery may be prompt and complete, or protracted withsequela

A sequela (, ; usually used in the plural, sequelae ) is a pathological condition resulting from a disease, injury, therapy, or other trauma. Derived from the Latin word, meaning “sequel”, it is used in the medical field to mean a complication ...

e, such as orchitis, hepatitis, uveitis, parotitis, desquamation, or alopecia. Importantly, MARV is known to be able to persist in some survivors and to either reactivate and cause a secondary bout of MVD or to be transmitted via sperm

Sperm is the male reproductive cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm with a tail known as a flagellum, whi ...

, causing secondary cases of infection and disease.

Of the 252 people who contracted Marburg during the 2004–2005 outbreak of a particularly virulent serotype in Angola, 227 died, for a case fatality rate of 90%.

Although all age groups are susceptible to infection, children are rarely infected. In the 1998–2000 Congo epidemic, only 8% of the cases were children less than 5 years old.

Epidemiology

Below is a table of outbreaks concerning MVD from 1967 to 2021:1967 outbreak

MVD was first documented in 1967, when 31 people became ill in theGerman

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

towns of Marburg and Frankfurt am Main, and in Belgrade

Belgrade ( , ;, ; Names of European cities in different languages: B, names in other languages) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city in Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers a ...

, Yugoslavia. The outbreak involved 25 primary MARV infections and seven deaths, and six nonlethal secondary cases. The outbreak was traced to infected grivet

The grivet (''Chlorocebus aethiops'') is an Old World monkey with long white tufts of hair along the sides of its face. Some authorities consider this and all of the members of the genus ''Chlorocebus'' to be a single species, ''Cercopithecus ae ...

s (species ''Chlorocebus aethiops'') imported from an undisclosed location in Uganda and used in developing poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 70% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe sym ...

vaccines. The monkeys were received by Behringwerke, a Marburg company founded by the first winner of the Nobel Prize in Medicine, Emil von Behring

Emil von Behring (; Emil Adolf von Behring), born Emil Adolf Behring (15 March 1854 – 31 March 1917), was a German physiologist who received the 1901 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, the first one awarded in that field, for his discovery ...

. The company, which at the time was owned by Hoechst Hoechst, Hochst, or Höchst may refer to:

* Hoechst AG, a former German life-sciences company

* Hoechst stain, one of a family of fluorescent DNA-binding compounds

* Höchst (Frankfurt am Main), a city district of Frankfurt am Main, Germany

** Fra ...

, was originally set up to develop sera against tetanus and diphtheria. Primary infections occurred in Behringwerke laboratory staff while working with grivet tissues or tissue cultures without adequate personal protective equipment. Secondary cases involved two physicians, a nurse, a post-mortem attendant, and the wife of a veterinarian. All secondary cases had direct contact, usually involving blood, with a primary case. Both physicians became infected through accidental skin pricks when drawing blood from patients. A popular science account of this outbreak can be found in Laurie Garrett

Laurie Garrett (born 1951) is an American science journalist and author. She was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Journalism in 1996 for a series of works published in '' Newsday'' that chronicled the Ebola virus outbreak in Zaire.

Bi ...

’s book ''The Coming Plague''.

1975 cases

In 1975, an Australian tourist became infected with MARV inRhodesia

Rhodesia (, ), officially from 1970 the Republic of Rhodesia, was an unrecognised state in Southern Africa from 1965 to 1979, equivalent in territory to modern Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was the ''de facto'' successor state to the British colony of S ...

(today Zimbabwe). He died in a hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. His girlfriend and an attending nurse were subsequently infected with MVD, but survived.

1980 cases

A case of MARV infection occurred in 1980 in Kenya. A French man, who worked as an electrical engineer in a sugar factory in Nzoia (close to Bungoma) at the base ofMount Elgon

Mount Elgon is an extinct shield volcano on the border of Uganda and Kenya, north of Kisumu and west of Kitale. The mountain's highest point, named "Wagagai", is located entirely within Uganda.

(which contains Kitum Cave), became infected by unknown means and died on 15 January shortly after admission to Nairobi Hospital. The attending physician contracted MVD, but survived. A popular science account of these cases can be found in Richard Preston’s book '' The Hot Zone'' (the French man is referred to under the pseudonym “Charles Monet”, whereas the physician is identified under his real name, Shem Musoke).

1987 case

In 1987, a single lethal case of RAVV infection occurred in a 15-year-old Danish boy, who spent his vacation in Kisumu, Kenya. He had visited Kitum Cave onMount Elgon

Mount Elgon is an extinct shield volcano on the border of Uganda and Kenya, north of Kisumu and west of Kitale. The mountain's highest point, named "Wagagai", is located entirely within Uganda.

prior to travelling to Mombasa, where he developed clinical signs of infection. The boy died after transfer to Nairobi Hospital. A popular science account of this case can be found in Richard Preston’s book '' The Hot Zone'' (the boy is referred to under the pseudonym “Peter Cardinal”).

1988 laboratory infection

In 1988, researcher Nikolai Ustinov infected himself lethally with MARV after accidentally pricking himself with a syringe used for inoculation of guinea pigs. The accident occurred at the Scientific-Production Association "Vektor" (today the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology "Vektor") in Koltsovo, USSR (today Russia). Very little information is publicly available about this MVD case because Ustinov's experiments were classified. A popular science account of this case can be found inKen Alibek

Kanatzhan "Kanat" Alibekov ( kk, Қанатжан Байзақұлы Әлібеков, Qanatjan Baizaqūly Älıbekov; russian: Канатжан Алибеков, Kanatzhan Alibekov; born 1950), known as Kenneth "Ken" Alibek since 1992, is a Kazak ...

’s book ''Biohazard''.

1990 laboratory infection

Another laboratory accident occurred at the Scientific-Production Association "Vektor" (today the State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology "Vektor") in Koltsovo, USSR, when a scientist contracted MARV by unknown means.1998–2000 outbreak

A major MVD outbreak occurred among illegal gold miners around Goroumbwa mine in Durba andWatsa

Watsa is a community in the Haut-Uele Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, administrative center of the Watsa Territory. It is served by Watsa Airport, a grass airstrip south of the town.

Watsa was the location of the VI battalion o ...

, Democratic Republic of Congo from 1998 to 2000, when co-circulating MARV and RAVV caused 154 cases of MVD and 128 deaths. The outbreak ended with the flooding of the mine.

2004–2005 outbreak

In early 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) began investigating an outbreak ofviral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses in which fever and hemorrhage are caused by a viral infection. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families ''Filoviridae'', ''Flavi ...

in Angola, which was centered in the northeastern Uíge Province

Uíge (pronunciation: ; kg, Wizidi) is one of the eighteen Provinces of Angola, located in the northwestern part of the country. Its capital city is of the same name.

History

During the Middle Ages, the Uíge Province was the heartland of the ...

but also affected many other provinces. The Angolan government had to ask for international assistance, pointing out that there were only approximately 1,200 doctors in the entire country, with some provinces having as few as two. Health care workers also complained about a shortage of personal protective equipment such as gloves, gowns, and masks. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reported that when their team arrived at the provincial hospital at the center of the outbreak, they found it operating without water and electricity. Contact tracing was complicated by the fact that the country's roads and other infrastructure were devastated after nearly three decades of civil war and the countryside remained littered with land mines. Americo Boa Vida Hospital in the Angolan capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

Luanda set up a special isolation ward to treat infected people from the countryside. Unfortunately, because MVD often results in death, some people came to view hospitals and medical workers with suspicion and treated helpers with hostility. For instance, a specially-equipped isolation ward at the provincial hospital in Uíge was reported to be empty during much of the epidemic, even though the facility was at the center of the outbreak. WHO was forced to implement what it described as a "harm reduction strategy", which entailed distributing disinfectants to affected families who refused hospital care. Of the 252 people who contracted MVD during outbreak, 227 died.

2007 cases

In 2007, fourminer

A miner is a person who extracts ore, coal, chalk, clay, or other minerals from the earth through mining. There are two senses in which the term is used. In its narrowest sense, a miner is someone who works at the rock face; cutting, blasting, ...

s became infected with marburgviruses in Kamwenge District

Kamwenge District is a district in Western Uganda. It is named after its 'chief town', Kamwenge, where the district headquarters are located. Kamwenge District is part of the Kingdom of Toro, one of the ancient traditional monarchies in Uganda. ...

, Uganda. The first case, a 29-year-old man, became symptomatic on July 4, 2007, was admitted to a hospital on July 7, and died on July 13. Contact tracing revealed that the man had had prolonged close contact with two colleagues (a 22-year-old man and a 23-year-old man), who experienced clinical signs of infection before his disease onset. Both men had been admitted to hospitals in June and survived their infections, which were proven to be due to MARV. A fourth, 25-year-old man, developed MVD clinical signs in September and was shown to be infected with RAVV. He also survived the infection.

2008 cases

On July 10, 2008, the Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment reported that a 41-year-old Dutch woman, who had visited Python Cave inMaramagambo Forest

Maramagambo Forest is located in Bushenyi, Uganda. It adjoins the Queen Elizabeth National Park to the north. It is jointly managed by the Uganda Wildlife Authority and the National Forestry Authority. It is associated with its bat cave where a ...

during her holiday in Uganda had MVD due to MARV infection, and had been admitted to a hospital in the Netherlands. The woman died under treatment in the Leiden University Medical Centre in Leiden on July 11. The Ugandan Ministry of Health closed the cave after this case. On January 9 of that year an infectious diseases physician notified the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment that a 44-year-old American woman who had returned from Uganda had been hospitalized with a fever of unknown origin

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) refers to a condition in which the patient has an elevated temperature (fever) but, despite investigations by a physician, no explanation has been found.

. At the time, serologic testing was negative for viral hemorrhagic fever

Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a diverse group of animal and human illnesses in which fever and hemorrhage are caused by a viral infection. VHFs may be caused by five distinct families of RNA viruses: the families ''Filoviridae'', ''Flavi ...

. She was discharged on January 19, 2008. After the death of the Dutch patient and the discovery that the American woman had visited Python Cave, further testing confirmed the patient demonstrated MARV antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

and RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

.

2017 Uganda outbreak

2021 Guinean cases

In August 2021, two months after the re-emergent Ebola epidemic in the Guéckédou prefecture was declared over, a case of the Marburg disease was confirmed by health authorities through laboratory analysis. Other potential case of the disease in a contact awaits official results. This was the first case of the Marburg hemorrhagic fever confirmed to happen in West Africa. The case of Marburg also has been identified in Guéckédou. During the outbreak, a total of one confirmed case who died, ( CFR=100%) and 173 contacts were identified, including 14 high risk contacts based on exposure. Among them, 172 were followed for a period of 21 days, of which none developed symptoms. One high-risk contact was lost to follow up. Sequencing of an isolate from the Guinean patient showed that this outbreak was caused by the Angola-like Marburg virus. A colony of Egyptian rousettus bats (reservoir host

In Infection, infectious disease ecology and epidemiology, a natural reservoir, also known as a disease reservoir or a reservoir of infection, is the population of organisms or the specific environment in which an infectious pathogen naturally li ...

of Marburg virus

Marburg virus (MARV) is a hemorrhagic fever virus of the ''Filoviridae'' family of viruses and a member of the species '' Marburg marburgvirus'', genus ''Marburgvirus''. It causes Marburg virus disease in primates, a form of viral hemorrhagic f ...

) was found in close proximity (4.5 km) to the village, where the Marburg virus disease outbreak emerged in 2021. Two of sampled fruit bats from this colony were PCR-positive on the Marburg virus.

2022 Ghanaian cases

In July 2022, preliminary analysis of samples taken from two patients – both deceased – in Ghana indicated the cases were positive for Marburg. However, per standard procedure, the samples were sent to thePasteur Institute of Dakar

The Institut Pasteur de Dakar (IPD) is a biomedical research center in Dakar, Senegal. The institute is part of the world-wide Pasteur Institute, which co-manages the IPD with the Senegalese government.

Description

In 1896 Émile Marchoux, a F ...

for confirmation. On 17 July 2022 the two cases were confirmed by Ghana, which caused the country to declare a Marburg virus disease outbreak. An additional case was identified, bringing the total to three.

Research

Experimentally, recombinant vesicular stomatitis Indiana virus (VSIV) expressing the glycoprotein of MARV has been used successfully in nonhuman primate models as post-exposure prophylaxis. A vaccine candidate has been effective in nonhuman primates. Experimental therapeutic regimens relying on antisense technology have shown promise, with phosphorodiamidate morpholino oligomers (PMOs) targeting the MARV genome New therapies from Sarepta and Tekmira have also been successfully used in humans as well as primates.See also

* List of other Filoviridae outbreaksReferences

Further reading

* * * * *External links

ViralZone: Marburg virus

* Centers for Disease Control,

Infection Control for Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers In the African Health Care Setting

'. * Center for Disease Control,

'. * Center for Disease Control,

' * * World Health Organization,

Marburg Haemorrhagic Fever

'.

Red Cross PDF

Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Filoviridae

{{Zoonotic viral diseases Animal viral diseases Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers Biological weapons Hemorrhagic fevers Tropical diseases Virus-related cutaneous conditions Zoonoses Marburgviruses