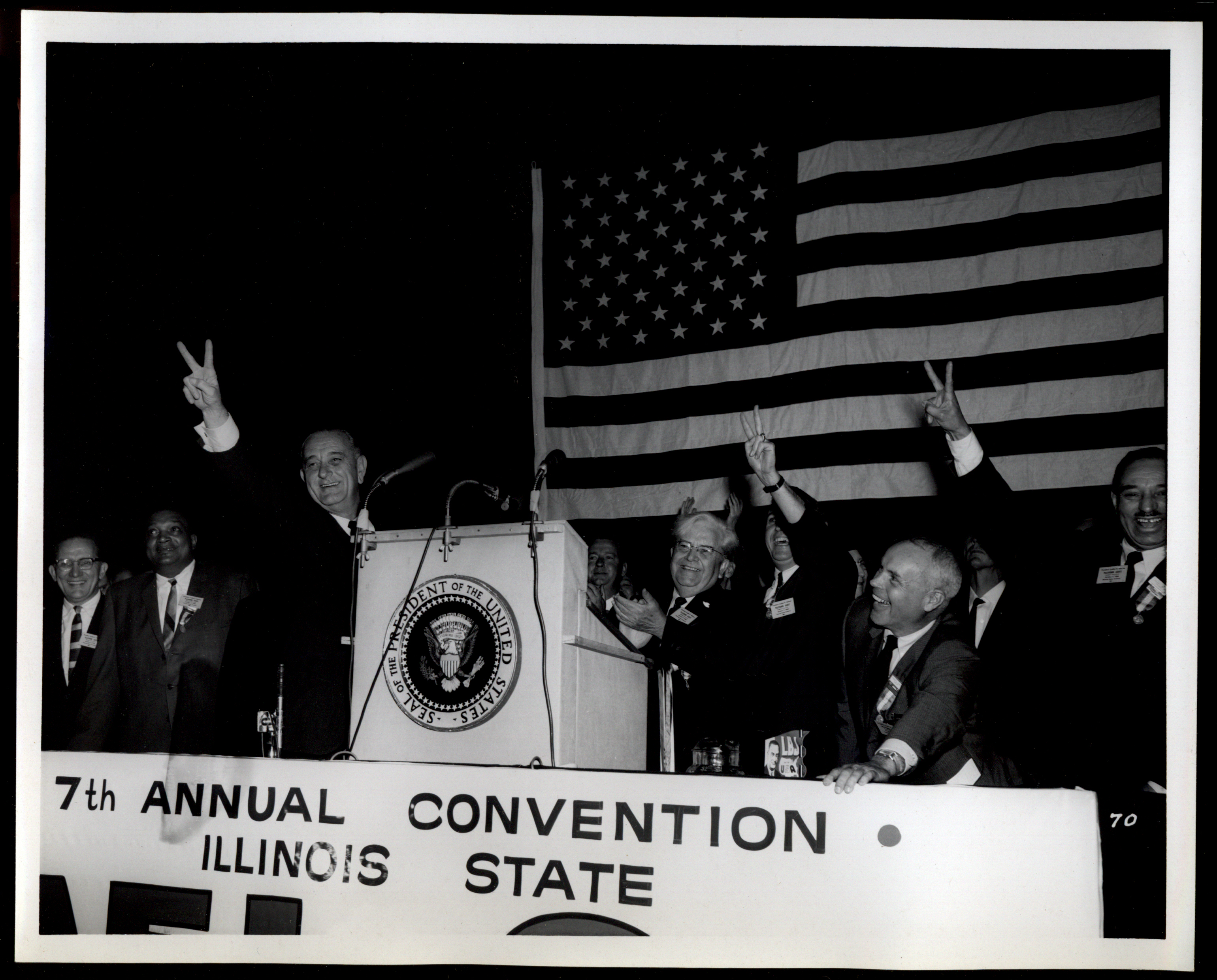

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th

vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

from 1961 to 1963 under President

John F. Kennedy, and was sworn in shortly after

Kennedy's assassination. A

Democrat from

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, Johnson also served as a

U.S. representative,

U.S. senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and power ...

and the Senate's

majority leader

In U.S. politics (as well as in some other countries utilizing the presidential system), the majority floor leader is a partisan position in a legislative body. . He holds the distinction of being one of the few presidents who served in all elected offices at the federal level.

Born in a farmhouse in

Stonewall, Texas, to a local political family, Johnson worked as a high school teacher and a congressional aide before winning election to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1937. He won

election to the United States Senate in 1948 after a narrow and controversial victory in the Democratic Party's primary. He was appointed to the position of

Senate Majority Whip in 1951. He became the Senate Democratic leader in 1953 and majority leader in 1954. In 1960 Johnson ran for the Democratic nomination for president. Ultimately, Senator Kennedy bested Johnson and his other rivals for the nomination, then surprised many by offering to make Johnson his vice presidential running mate. The Kennedy-Johnson ticket won in the

1960 presidential election. Vice President Johnson assumed the presidency on November 22, 1963, after President Kennedy was assassinated. The following year Johnson was elected to the presidency when he won in a landslide against Arizona Senator

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for president ...

, receiving 61.1% of the popular vote in the

1964 presidential election, the

largest share won by any presidential candidate since the

1820 election.

Johnson's domestic policy was aimed at expanding

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

,

public broadcasting

Public broadcasting involves radio, television and other electronic media outlets whose primary mission is public service. Public broadcasters receive funding from diverse sources including license fees, individual contributions, public financing ...

, access to

healthcare

Health care or healthcare is the improvement of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in people. Health care is delivered by health pro ...

, aid to education and the arts, urban and rural development, and public services. In 1964 Johnson coined the term the "

Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the Universit ...

" to describe these efforts. In addition, he sought to create better living conditions for low-income Americans by spearheading a campaign unofficially called the "

War on Poverty

The war on poverty is the unofficial name for legislation first introduced by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during his State of the Union address on January 8, 1964. This legislation was proposed by Johnson in response to a nationa ...

". As part of these efforts, Johnson signed the

Social Security Amendments of 1965

The Social Security Amendments of 1965, , was legislation in the United States whose most important provisions resulted in creation of two programs: Medicare and Medicaid. The legislation initially provided federal health insurance for the elder ...

, which resulted in the creation of

Medicare and

Medicaid

Medicaid in the United States is a federal and state program that helps with healthcare costs for some people with limited income and resources. Medicaid also offers benefits not normally covered by Medicare, including nursing home care and per ...

. Johnson followed his predecessor's actions in bolstering

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

and made the

Apollo Program a national priority. He enacted the

Higher Education Act of 1965

The Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA) () was legislation signed into United States law on November 8, 1965, as part of President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society domestic agenda. Johnson chose Texas State University (then called "Southwest Tex ...

which established federally insured student loans. Johnson signed the

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act and more recently as the 1965 Immigration Act, is a federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The ...

which laid the groundwork for U.S. immigration policy today. Johnson's opinion on the issue of civil rights put him at odds with other white, southern Democrats. His civil rights legacy was shaped by signing the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requi ...

, the

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights m ...

, and the

Civil Rights Act of 1968

The Civil Rights Act of 1968 () is a landmark law in the United States signed into law by United States President Lyndon B. Johnson during the King assassination riots.

Titles II through VII comprise the Indian Civil Rights Act, which appl ...

. During his presidency, the American political landscape transformed significantly, as white southerners who were once staunch Democrats began moving to the

Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

* Republican Party (Liberia)

*Republican Party ...

and

black voters began moving to the Democratic Party. Because of his domestic agenda, Johnson's presidency marked the peak of

modern liberalism in the United States

Modern liberalism in the United States, often simply referred to in the United States as liberalism, is a form of social liberalism found in American politics. It combines ideas of civil liberty and equality with support for social justice a ...

.

Johnson's presidency took place during the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

and thus he prioritized

halting the expansion of

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

. Prior to his presidency, the U.S. was already involved in the Vietnam War, supporting

South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

against the communist

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north ...

. Following a

naval skirmish in 1964 between the United States and North Vietnam,

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

passed the

Gulf of Tonkin Resolution

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution or the Southeast Asia Resolution, , was a joint resolution that the United States Congress passed on August 7, 1964, in response to the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

It is of historic significance because it gave U.S. p ...

, which granted Johnson the power to launch a full-scale military intervention in South East Asia. The number of American military personnel in Vietnam increased dramatically, and

casualties soared among U.S. soldiers and Vietnamese civilians. Johnson also expanded

military operations in neighboring

Laos

Laos (, ''Lāo'' )), officially the Lao People's Democratic Republic ( Lao: ສາທາລະນະລັດ ປະຊາທິປະໄຕ ປະຊາຊົນລາວ, French: République démocratique populaire lao), is a socialist s ...

to destroy

North Vietnamese supply lines. In 1968, the communist

Tet Offensive

The Tet Offensive was a major escalation and one of the largest military campaigns of the Vietnam War. It was launched on January 30, 1968 by forces of the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) against the forces o ...

inflamed the anti-war movement, especially among

draft

Draft, The Draft, or Draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a vesse ...

-age students on university campuses, and public opinion turned against America's involvement in the war.

At home, Johnson faced further troubles with

race riots

An ethnic conflict is a conflict between two or more contending ethnic groups. While the source of the conflict may be political, social, economic or religious, the individuals in conflict must expressly fight for their ethnic group's positio ...

in major cities and increasing crime rates. His political opponents seized the opportunity and raised demands for

"law and order" policies. Johnson began his presidency with near-universal support, but his approval declined throughout his presidency as the public became frustrated with both the Vietnam War and domestic unrest. Johnson initially sought to run for re-election; however, following

disappointing results in the New Hampshire primary he withdrew his candidacy. The war was a major election issue and the

1968 presidential election saw Republican candidate

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

defeat Johnson's vice president

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing ...

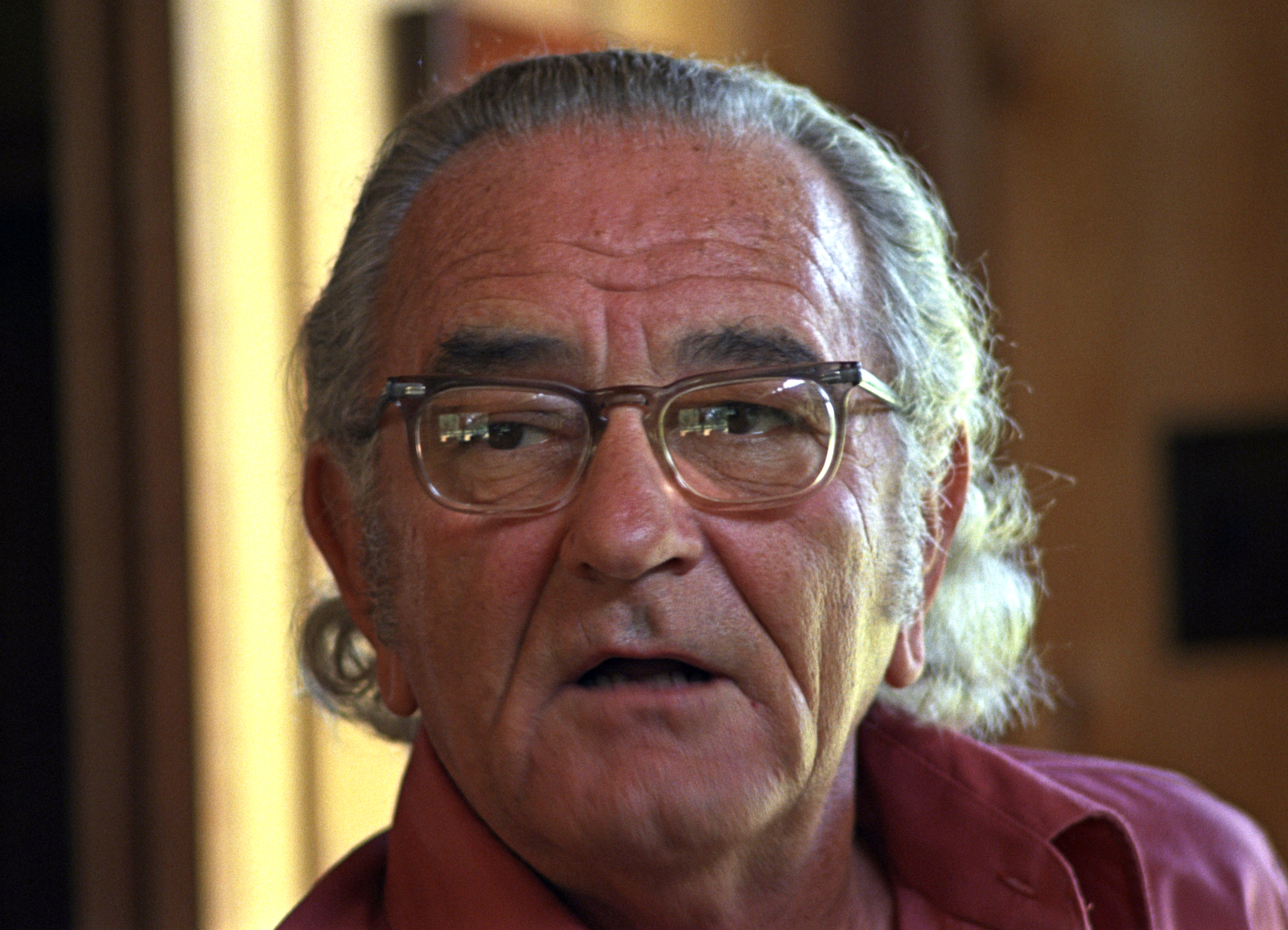

. At the end of his presidency in 1969, Johnson returned to his Texas ranch, published his memoirs, and in other respects kept a low profile until he died of a

heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

in 1973.

Johnson is one of the most controversial presidents in American history; public opinion and scholastic assessment of his legacy have continuously evolved since his death. Historians and scholars

rank Johnson in the upper tier because of his accomplishments regarding domestic policy. His administration passed many major laws that made substantial advancements in

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

,

health care

Health care or healthcare is the improvement of health via the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in people. Health care is delivered by health pr ...

,

welfare

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

, and

education

Education is a purposeful activity directed at achieving certain aims, such as transmitting knowledge or fostering skills and character traits. These aims may include the development of understanding, rationality, kindness, and honesty ...

. Conversely, Johnson is strongly criticized for his foreign policy, namely escalating American involvement in the Vietnam War.

Early life

Lyndon Baines Johnson was born on August 27, 1908, near

Stonewall, Texas, in a small farmhouse on the

Pedernales River. He was the eldest of five children born to

Samuel Ealy Johnson Jr.

Samuel Ealy Johnson Jr. (October 11, 1877 – October 23, 1937) was an American businessman and politician. He was a Democratic member of the Texas House of Representatives representing the 89th District. He served in the 29th, 30th, 35th, ...

and Rebekah Baines. Johnson had one brother,

Sam Houston Johnson

Samuel Houston Johnson (January 31, 1914 – December 11, 1978) was an American businessman. He was the younger brother of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Early life

Sam Houston Johnson was born in Johnson City, Texas on January 31, 1914, to Sam ...

, and three sisters, Rebekah, Josefa, and Lucia. The nearby small town of

Johnson City, Texas

Johnson City is a city and the county seat of Blanco County, Texas, United States. The population was 1,656 at the 2010 census. Founded in 1879 by James P. Johnson, it was named for early settler Sam E. Johnson, Sr. Johnson City is part ...

, was named after LBJ's father's cousin, James Polk Johnson, whose forebears had moved west from

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Johnson had

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

-

Irish,

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

, and

Ulster Scots ancestry. Through his mother, he was a great-grandson of pioneer Baptist clergyman

George Washington Baines, who pastored eight churches in Texas, as well as others in Arkansas and Louisiana. Baines was also the president of

Baylor University

Baylor University is a private Baptist Christian research university in Waco, Texas. Baylor was chartered in 1845 by the last Congress of the Republic of Texas. Baylor is the oldest continuously operating university in Texas and one of th ...

during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

.

Johnson's grandfather,

Samuel Ealy Johnson Sr.

Samuel Ealy Johnson, Sr. (November 12, 1838 – February 25, 1915) was an American politician, businessman, farmer, rancher, and namesake of Johnson City, Texas. He was the grandfather of U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson.

Early life

Johnso ...

, was raised as a Baptist and for a time was a member of the

Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

. In his later years, the grandfather became a

Christadelphian

The Christadelphians () or Christadelphianism are a restorationist and millenarian Christian group who hold a view of biblical unitarianism. There are approximately 50,000 Christadelphians in around 120 countries. The movement developed in the ...

; Johnson's father also joined the Christadelphian Church toward the end of his life. Later, as a politician, Johnson was influenced in his positive attitude toward Jews by the religious beliefs that his

family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

, especially his grandfather, had shared with him. Johnson's favorite Bible verse came from the King James Version of

Isaiah 1:18 "Come now, and let us reason together..."

In school, Johnson was a talkative youth who was elected president of his 11th-grade class. He graduated in 1924 from

Johnson City High School

Lyndon Baines Johnson High School or LBJ High School is a public high school located in Johnson City, Texas ( USA) and classified as a 3A school by the UIL. It is part of the Johnson City Independent School District located in north central Bla ...

, where he participated in public speaking, debate, and baseball.

[Caro 1982.] At the age of 15, Johnson was the youngest member of his class. Pressured by his parents to attend college, he enrolled at a "sub college" of Southwest Texas State Teachers College (SWTSTC) in the summer of 1924, where students from unaccredited high schools could take the 12th-grade courses needed for admission to college. He left the school just weeks after his arrival and decided to move to

southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most populous urban ...

. He worked at his cousin's legal practice and in various odd jobs before returning to Texas, where he worked as a day laborer.

In 1926, Johnson managed to enroll at SWTSTC (now

Texas State University

Texas State University is a public research university in San Marcos, Texas. Since its establishment in 1899, the university has grown to the second largest university in the Greater Austin metropolitan area and the fifth largest university ...

). He worked his way through school, participated in debate and campus politics, and edited the school newspaper,

''The College Star''. The college years refined his skills of persuasion and political organization. For nine months, from 1928 to 1929, Johnson paused his studies to teach Mexican–American children at the segregated Welhausen School in

Cotulla, some south of

San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

in

La Salle County. The job helped him to save money to complete his education, and he graduated in 1930 with a

Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

degree in history and his certificate of qualification as a high school teacher. He briefly taught at

Pearsall High School before taking a position as teacher of public speaking at

Sam Houston High School in Houston.

When he returned to San Marcos in 1965, after signing the

Higher Education Act of 1965

The Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA) () was legislation signed into United States law on November 8, 1965, as part of President Lyndon Johnson's Great Society domestic agenda. Johnson chose Texas State University (then called "Southwest Tex ...

, Johnson reminisced:

Entry into politics

After

Richard M. Kleberg

Richard Mifflin Kleberg Sr. (November 18, 1887 – May 8, 1955), a Democrat, was a seven-term member of the United States House of Representatives from Texas's 14th congressional district over the period 1931–1945 and an heir to the King Ranch ...

won a 1931 special election to represent Texas in the

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

, he appointed Johnson as his legislative secretary. This marked Johnson's formal introduction into politics. Johnson secured the position on the recommendation of his father and that of State Senator Welly Hopkins, for whom Johnson had campaigned in 1930. Kleberg had little interest in performing the day-to-day duties of a Congressman, instead delegating them to Johnson. After

Franklin D. Roosevelt won the

1932 presidential election, Johnson became a lifelong supporter of Roosevelt's

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

. Johnson was elected speaker of the "Little Congress", a group of Congressional aides, where he cultivated Congressmen, newspapermen, and lobbyists. Johnson's friends soon included aides to President Roosevelt as well as fellow Texans such as Vice President

John Nance Garner

John Nance Garner III (November 22, 1868 – November 7, 1967), known among his contemporaries as "Cactus Jack", was an American Democratic politician and lawyer from Texas who served as the 32nd vice president of the United States under Fran ...

and Congressman

Sam Rayburn

Samuel Taliaferro Rayburn (January 6, 1882 – November 16, 1961) was an American politician who served as the 43rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a three-time House speaker, former House majority leader, two-time ...

.

Johnson married

Claudia Alta Taylor, also known as "Lady Bird", of

Karnack, Texas Karnack is a rural unincorporated community in northeastern Harrison County near Caddo Lake in the eastern region of the U.S. state of Texas.

The town is named after Karnak, Egypt (near modern-day Luxor). It was thought that the community's ali ...

, on November 17, 1934. He met her after he had attended

Georgetown University Law Center

The Georgetown University Law Center (Georgetown Law) is the law school of Georgetown University, a private research university in Washington, D.C. It was established in 1870 and is the largest law school in the United States by enrollment and ...

for several months. Johnson later quit his Georgetown studies after the first semester in 1934. During their first date he asked her to marry him; many dates later, she finally agreed. The wedding was officiated by

Arthur R. McKinstry at

St. Mark's Episcopal Church in

San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

. They had two daughters,

Lynda Bird, born in 1944, and

Luci Baines, born in 1947. Johnson gave his children names with the LBJ initials; his dog was Little Beagle Johnson. His home was the

LBJ Ranch; his initials were on his cufflinks, ashtrays, and clothes.

During his marriage, Lyndon Johnson had

affairs with "numerous"

women, in particular with Alice Marsh (''

née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

'' Glass) who assisted him politically.

In 1935, he was appointed head of the Texas

National Youth Administration

The National Youth Administration (NYA) was a New Deal agency sponsored by Franklin D. Roosevelt during his presidency. It focused on providing work and education for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25. It operated from June 26, 1935 to ...

, which enabled him to use the government to create education and job opportunities for young people. He resigned two years later to run for Congress. Johnson, a notoriously tough boss throughout his career, often demanded long workdays and work on weekends. He was described by friends, fellow politicians, and historians as motivated by an exceptional lust for power and control. As Johnson's biographer

Robert Caro

Robert Allan Caro (born October 30, 1935) is an American journalist and author known for his biographies of United States political figures Robert Moses and Lyndon B. Johnson.

After working for many years as a reporter, Caro wrote '' The Power ...

observes, "Johnson's ambition was uncommonin the degree to which it was unencumbered by even the slightest excess weight of ideology, of philosophy, of principles, of beliefs."

U.S. House of Representatives (1937–1949)

In 1937, after the death of thirteen-term Congressman

James P. Buchanan

James Paul "Buck" Buchanan (April 30, 1867 – February 22, 1937) served as U.S. Representative from the 10th district of Texas from 1913 until his death on February 22, 1937.

Biography

Buchanan was born in Midway, Orangeburg County, South Carol ...

, Johnson successfully campaigned in a special election for

Texas's 10th congressional district, that covered

Austin

Austin is the capital city of the U.S. state of Texas, as well as the seat and largest city of Travis County, with portions extending into Hays and Williamson counties. Incorporated on December 27, 1839, it is the 11th-most-populous city ...

and the surrounding hill country. He ran on a New Deal platform and was effectively aided by his wife. He served in the House from April 10, 1937, to January 3, 1949.

President

Franklin D. Roosevelt found Johnson to be a welcome ally and conduit for information, particularly about issues concerning internal politics in Texas (

Operation Texas

Operation Texas was an alleged undercover operation to relocate European Jews to Texas, USA, away from Nazi persecution, first reported in a 1989 Ph.D. dissertation by Louis Stanislaus Gomolak at the University of Texas at Austin titled ''Prolog ...

) and the machinations of Vice President

John Nance Garner

John Nance Garner III (November 22, 1868 – November 7, 1967), known among his contemporaries as "Cactus Jack", was an American Democratic politician and lawyer from Texas who served as the 32nd vice president of the United States under Fran ...

and

Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hunger ...

Sam Rayburn

Samuel Taliaferro Rayburn (January 6, 1882 – November 16, 1961) was an American politician who served as the 43rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a three-time House speaker, former House majority leader, two-time ...

. Johnson was immediately appointed to the

Naval Affairs Committee. He worked for rural electrification and other improvements for his district. Johnson steered the projects towards contractors he knew, such as

Herman and George Brown, who would finance much of Johnson's future career.

In 1941, he ran for the Democratic U.S. Senate nomination in a special election, losing narrowly to the sitting

Governor of Texas

The governor of Texas heads the state government of Texas. The governor is the leader of the executive and legislative branch of the state government and is the commander in chief of the Texas Military. The current governor is Greg Abbott, w ...

, businessman and radio personality

W. Lee O'Daniel

Wilbert Lee "Pappy" O'Daniel (March 11, 1890May 11, 1969) was an American Democratic Party politician from Texas, who came to prominence by hosting a popular radio program. Known for his populist appeal and support of Texas's business communi ...

. O'Daniel received 175,590 votes (30.49 percent) to Johnson's 174,279 (30.26 percent).

Active military duty (1941–1942)

Johnson was appointed a

Lieutenant Commander

Lieutenant commander (also hyphenated lieutenant-commander and abbreviated Lt Cdr, LtCdr. or LCDR) is a commissioned officer rank in many navies. The rank is superior to a lieutenant and subordinate to a commander. The corresponding ran ...

in the

U.S. Naval Reserve on June 21, 1940. While serving as a U.S. representative, he was called to active duty three days after the Japanese

attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii ...

in December 1941. His orders were to report to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations in Washington, D.C., for instruction and training.

Following his training, he asked Undersecretary of the Navy

James Forrestal for a job in Washington. He was sent instead to inspect shipyard facilities in Texas and on the West Coast. In the spring of 1942, President Roosevelt decided he needed better information on conditions in the

Southwest Pacific, and to send a highly trusted political ally to get it. From a suggestion by Forrestal, Roosevelt assigned Johnson to a three-man survey team covering the Southwest Pacific.

[Dallek 1991, pp. 235–245.]

Johnson reported to General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

in Australia. Johnson and two U.S. Army officers went to the

22nd Bomb Group base, which was assigned the high-risk mission of bombing the Japanese airbase at

Lae in

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; id, Papua, or , historically ) is the world's second-largest island with an area of . Located in Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is separated from Australia by the wide Torres ...

. On June 9, 1942, Johnson volunteered as an observer for an airstrike on New Guinea by

B-26 bombers. Reports vary on what happened to the aircraft carrying Johnson during that mission. Johnson's biographer

Robert Caro

Robert Allan Caro (born October 30, 1935) is an American journalist and author known for his biographies of United States political figures Robert Moses and Lyndon B. Johnson.

After working for many years as a reporter, Caro wrote '' The Power ...

accepts Johnson's account and supports it with testimony from the aircrew concerned: the aircraft was attacked, disabling one engine and it turned back before reaching its objective, though remaining under heavy fire. Others claim that it turned back because of generator trouble before reaching the objective and before encountering enemy aircraft and never came under fire; this is supported by official flight records.

[LBJ's medal for valour 'was sham'](_blank)

''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers '' The Observer'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the ...

'', July 6, 2001 Other airplanes that continued to the target came under fire near the target about the same time Johnson's plane was recorded as having landed back at the original airbase. MacArthur recommended Johnson for the

Silver Star

The Silver Star Medal (SSM) is the United States Armed Forces' third-highest military decoration for valor in combat. The Silver Star Medal is awarded primarily to members of the United States Armed Forces for gallantry in action against an e ...

for gallantry in action: the only member of the crew to receive a decoration.

After it was approved by the Army, he presented the medal to Johnson, with the following citation:

Johnson, who had used a movie camera to record conditions, reported to Roosevelt, to Navy leaders, and Congress that conditions were deplorable and unacceptable: some historians have suggested this was in exchange for MacArthur's recommendation to award the Silver Star.

He argued that the southwest Pacific urgently needed a higher priority and a larger share of war supplies. The warplanes sent there, for example, were "far inferior" to Japanese planes; and morale was bad. He told Forrestal that the Pacific Fleet had a "critical" need for 6,800 additional experienced men. Johnson prepared a twelve-point program to upgrade the effort in the region, stressing "greater cooperation and coordination within the various commands and between the different war theaters". Congress responded by making Johnson chairman of a high-powered subcommittee of the Naval Affairs Committee, with a mission similar to that of the

Truman Committee

The Truman Committee, formally known as the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, was a United States congressional committee, United States Congressional investigative body, headed by United States Senator, Senat ...

in the Senate. He probed the peacetime "business as usual" inefficiencies that permeated the naval war and demanded that admirals shape up and get the job done. Johnson went too far when he proposed a bill that would crack down on the draft exemptions of shipyard workers if they were absent from work too often; organized labor blocked the bill and denounced him. Johnson's biographer

Robert Dallek

Robert A. Dallek (born May 16, 1934) is an American historian specializing in the presidents of the United States, including Franklin D. Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard Nixon. He retired as a history professor at Bost ...

concludes, "The mission was a temporary exposure to danger calculated to satisfy Johnson's personal and political wishes, but it also represented a genuine effort on his part, however misplaced, to improve the lot of America's fighting men."

In addition to the Silver Star, Johnson received the

American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had perfo ...

,

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and the

World War II Victory Medal

The World War II Victory Medal is a service medal of the United States military which was established by an Act of Congress on 6 July 1945 (Public Law 135, 79th Congress) and promulgated by Section V, War Department Bulletin 12, 1945.

The Wo ...

. He was released from active duty on July 17, 1942, and remained in the Navy Reserve, later promoted to

Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain. ...

on October 19, 1949 (effective June 2, 1948). He resigned from the Navy Reserve effective January 18, 1964.

U.S. Senate (1949–1961)

1948 U.S. Senate election

In the

1948 elections, Johnson again ran for the Senate and won in a highly controversial Democratic Party

primary

Primary or primaries may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Primary (band), from Australia

* Primary (musician), hip hop musician and record producer from South Korea

* Primary Music, Israeli record label

Works

...

against the well-known former governor

Coke Stevenson

Coke Robert Stevenson (March 20, 1888 – June 28, 1975) was an American politician who served as the 35th governor of Texas from 1941 to 1947. He was the first Texan politician to hold its three highest offices (Speaker of the Texas House ...

. Johnson drew crowds to fairgrounds with his rented helicopter, dubbed "The Johnson City Windmill". He raised money to flood the state with campaign circulars and won over conservatives by casting doubts on Stevenson's support for the

Taft–Hartley Act

The Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, better known as the Taft–Hartley Act, is a Law of the United States, United States federal law that restricts the activities and power of trade union, labor unions. It was enacted by the 80th United S ...

(curbing union power). Stevenson came in first in the primary but lacked a majority, so a runoff election was held; Johnson campaigned harder, while Stevenson's efforts slumped due to a lack of funds.

US presidential historian

Michael Beschloss observed that Johnson "gave

white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

speeches" during the 1948 campaign, in order to secure the white vote. This cemented his reputation as a moderate in American politics, which would enable his ability to pivot and further civil rights causes upon assuming the presidency.

The runoff vote count, handled by the Democratic State Central Committee, took a week. Johnson was announced the winner by 87 votes out of 988,295, an extremely narrow margin of victory. However, Johnson's victory was based on 200 "patently fraudulent"

ballots reported six days after the election from

Box 13 in

Jim Wells County

Jim Wells County is a county in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2020 census, its population was 38,891. The county was founded in 1911 and is named for James B. Wells, Jr. (1850-1923), for three decades a judge and Democratic Party poli ...

, in an area dominated by political boss

George Parr. The added names were in alphabetical order and written with the same pen and handwriting, following at the end of the list of voters. Some of the persons in this part of the list insisted that they had not voted that day. Election judge Luis Salas said in 1977 that he had certified 202 fraudulent ballots for Johnson.

Robert Caro

Robert Allan Caro (born October 30, 1935) is an American journalist and author known for his biographies of United States political figures Robert Moses and Lyndon B. Johnson.

After working for many years as a reporter, Caro wrote '' The Power ...

made the case in his 1990 book that Johnson had stolen the election in Jim Wells County, and that there were thousands of fraudulent votes in other counties as well, including 10,000 votes switched in

San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

. The Democratic State Central Committee voted to certify Johnson's nomination by a majority of one (29–28), with the last vote cast on Johnson's behalf by the publisher Frank W. Mayborn of

Temple, Texas

Temple is a city in Bell County, Texas, United States. As of 2020, the city has a population of 82,073 according to the U.S. census, and is one of the two principal cities in Bell County.

Located near the county seat of Belton, Temple lies in ...

. The state Democratic convention upheld Johnson. Stevenson went to court, eventually taking his case before the

U.S. Supreme Court, but with timely help from his friend and future U.S. Supreme Court Justice

Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from R ...

, Johnson prevailed on the basis that jurisdiction over naming a nominee rested with the party, not the federal government. Johnson soundly defeated Republican

Jack Porter in the general election in November and went to Washington, permanently dubbed "Landslide Lyndon". Johnson, dismissive of his critics, happily adopted the nickname.

Freshman senator to majority whip

Once in the Senate, Johnson was known among his colleagues for his highly successful "courtships" of older senators, especially Senator

Richard Russell, Democrat from Georgia, the leader of the

Conservative coalition

The conservative coalition, founded in 1937, was an unofficial alliance of members of the United States Congress which brought together the conservative wings of the Republican and Democratic parties to oppose President Franklin Delano Roosev ...

and arguably the most powerful man in the Senate. Johnson proceeded to gain Russell's favor in the same way he had "courted" Speaker Sam Rayburn and gained his crucial support in the House.

Johnson was appointed to the Senate Armed Services Committee, and in 1950 helped create the Preparedness Investigating Subcommittee. He became its chairman, and conducted investigations of defense costs and efficiency. These investigations revealed old investigations and demanded actions that were already being taken in part by the

Truman administration, although it can be said that the committee's investigations reinforced the need for changes. Johnson gained headlines and national attention through his handling of the press, the efficiency with which his committee issued new reports, and the fact that he ensured that every report was endorsed unanimously by the committee. He used his political influence in the Senate to receive broadcast licenses from the

Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains jurisdicti ...

in his wife's name.

After the 1950 general elections, Johnson was chosen as Senate Majority Whip in 1951 under the new Majority Leader,

Ernest McFarland

Ernest William McFarland (October 9, 1894 – June 8, 1984) was an American politician, jurist and, with Warren Atherton, one of the "Fathers of the G.I. Bill." He is the only Arizonan to serve in the highest office in all three branches of Ari ...

of

Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

, and served from 1951 to 1953.

Senate Democratic leader

In the

1952 general election,

Republicans won a majority in both the House and Senate. Among defeated Democrats that year was McFarland, who lost to upstart

Barry Goldwater

Barry Morris Goldwater (January 2, 1909 – May 29, 1998) was an American politician and United States Air Force officer who was a five-term U.S. Senator from Arizona (1953–1965, 1969–1987) and the Republican Party nominee for president ...

. In January 1953, Johnson was chosen by his fellow Democrats to be Minority Leader; he became the most junior senator ever elected to this position. One of his first actions was to eliminate the seniority system in making appointments to committees while retaining it for chairmanships. In the

1954 election, Johnson was re-elected to the Senate and, since the Democrats won the majority in the Senate, then became majority leader. Former Majority Leader

William Knowland

William Fife Knowland (June 26, 1908 – February 23, 1974) was an American politician and newspaper publisher. A member of the Republican Party, he served as a United States Senator from California from 1945 to 1959. He was Senate Majority Le ...

of California became the Minority Leader. Johnson's duties were to schedule legislation and help pass measures favored by the Democrats. Johnson, Rayburn and President

Dwight D. Eisenhower worked well together in passing Eisenhower's domestic and foreign agenda.

During the

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

, Johnson tried to prevent the U.S. government from criticizing the Israeli invasion of the Sinai peninsula. Along with the rest of the nation, Johnson was appalled by the threat of possible

Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

domination of space flight implied by the launch of the first artificial Earth satellite ''

Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for ...

'' and used his influence to ensure passage of the 1958

National Aeronautics and Space Act

The National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 () is the United States federal statute that created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The Act, which followed close on the heels of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union ...

, which established the civilian space agency

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

.

Historians Caro and Dallek consider Lyndon Johnson the most effective Senate majority leader in history. He was unusually proficient at gathering information. One biographer suggests he was "the greatest intelligence gatherer Washington has ever known", discovering exactly where every senator stood on issues, his philosophy and prejudices, his strengths and weaknesses and what it took to get his vote. Robert Baker claimed that Johnson would occasionally send senators on NATO trips to avoid their dissenting votes. Central to Johnson's control was "The Treatment", described by two journalists:

In 1955, Johnson persuaded Oregon's Independent

Wayne Morse

Wayne Lyman Morse (October 20, 1900 – July 22, 1974) was an American attorney and United States Senator from Oregon. Morse is well known for opposing his party's leadership and for his opposition to the Vietnam War on constitutional grounds.

...

to join the Democratic caucus.

A 60-cigarette-per-day smoker, Johnson suffered a near-fatal heart attack on July 2, 1955, at age 46. He abruptly gave up smoking as a result and, with only a couple of exceptions, did not resume the habit until after he left the White House on January 20, 1969. Johnson announced he would remain as his party's leader in the Senate on New Year's Eve 1955, his doctors reporting he had made "a most satisfactory recovery" since his heart attack five months before.

Campaigns of 1960

Johnson's success in the Senate rendered him a potential Democratic presidential candidate; he had been the "

favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term.

* At the quadrennial American national political party conventions, a state delegation sometimes nominates a candidate from the state, or less often from the state's region, who is not a ...

" candidate of the Texas delegation at the Party's national convention in 1956, and appeared to be in a strong position to run for the 1960 nomination.

Jim Rowe repeatedly urged Johnson to launch a campaign in early 1959, but Johnson thought it better to wait, thinking that John Kennedy's efforts would create a division in the ranks which could then be exploited. Rowe finally joined the Humphrey campaign in frustration, another move that Johnson thought played into his own strategy.

Candidacy for president

Johnson made a late entry into the campaign in July 1960 which, coupled with a reluctance to leave Washington, allowed the rival Kennedy campaign to secure a substantial early advantage among Democratic state party officials. Johnson underestimated Kennedy's endearing qualities of charm and intelligence, as compared to his reputation as the more crude and wheeling-dealing "Landslide Lyndon". Caro suggests that Johnson's hesitancy was the result of an overwhelming fear of failure.

Johnson attempted in vain to capitalize on Kennedy's youth, poor health, and failure to take a position regarding Joseph McCarthy and

McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origin ...

. He had formed a "Stop Kennedy" coalition with

Adlai Stevenson,

Stuart Symington

William Stuart Symington III (; June 26, 1901 – December 14, 1988) was an American businessman and Democratic politician from Missouri. He served as the first Secretary of the Air Force from 1947 to 1950 and was a United States Senator from ...

, and

Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing ...

, but it proved a failure. Despite Johnson having the support of established Democrats and the party leadership, this did not translate into popular approval. Johnson received 409 votes on the only ballot at the Democratic convention to Kennedy's 806, and so the convention nominated Kennedy.

Tip O'Neill

Thomas Phillip "Tip" O'Neill Jr. (December 9, 1912 – January 5, 1994) was an American politician who served as the 47th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1977 to 1987, representing northern Boston, Massachusetts, as ...

was a representative from Kennedy's home state of

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

at that time, and he recalled that Johnson approached him at the convention and said, "Tip, I know you have to support Kennedy at the start, but I'd like to have you with me on the second ballot." O'Neill replied, "Senator, there's not going to be any second ballot."

Vice-presidential nomination

According to Kennedy's Special Counsel

Myer Feldman

Myer Feldman, known as Mike Feldman (June 22, 1914 – March 1, 2007), was an American political aide in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. Hailing from Philadelphia, Feldman was a trained lawyer and alumnus of the University of Pennsylvan ...

and Kennedy himself, it is impossible to reconstruct the precise manner in which Johnson's vice-presidential nomination ultimately took place. Kennedy did realize that he could not be elected without the support of traditional

Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats wi ...

, most of whom had backed Johnson; nevertheless, labor leaders were unanimous in their opposition to Johnson. AFL-CIO President

George Meany

William George Meany (August 16, 1894 – January 10, 1980) was an American labor union leader for 57 years. He was the key figure in the creation of the AFL–CIO and served as the AFL–CIO's first president, from 1955 to 1979.

Meany, the son ...

called Johnson "the arch-foe of labor", while Illinois AFL-CIO President

Reuben Soderstrom

Reuben George Soderstrom (March 10, 1888 – December 15, 1970) was an American leader of organized labor who served as President of the Illinois State Federation of Labor (ISFL) and Illinois AFL-CIO from 1930 to 1970. A key figure in Chicago a ...

asserted Kennedy had "made chumps out of leaders of the American labor movement". After much back and forth with party leaders and others on the matter, Kennedy did offer Johnson the vice-presidential nomination at the

Los Angeles Biltmore Hotel at 10:15 am on July 14, the morning after he was nominated, and Johnson accepted. From that point to the actual nomination that evening, the facts are in dispute in many respects. (Convention chairman

LeRoy Collins' declaration of a two-thirds majority in favor by voice vote is even disputed.)

Seymour Hersh stated that

Robert F. Kennedy (known as Bobby) hated Johnson for his attacks on the Kennedy family, and later maintained that his brother offered the position to Johnson merely as a courtesy, expecting him to decline.

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. concurred with Robert Kennedy's version of events, and put forth that John Kennedy would have preferred

Stuart Symington

William Stuart Symington III (; June 26, 1901 – December 14, 1988) was an American businessman and Democratic politician from Missouri. He served as the first Secretary of the Air Force from 1947 to 1950 and was a United States Senator from ...

as his

running-mate, alleging that Johnson teamed with

House Speaker Sam Rayburn

Samuel Taliaferro Rayburn (January 6, 1882 – November 16, 1961) was an American politician who served as the 43rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a three-time House speaker, former House majority leader, two-time ...

and pressured Kennedy to favor Johnson. Robert Kennedy wanted his brother to choose labor leader

Walter Reuther

Walter Philip Reuther (; September 1, 1907 – May 9, 1970) was an American leader of organized labor and civil rights activist who built the United Automobile Workers (UAW) into one of the most progressive labor unions in American history. He ...

.

Biographer Robert Caro offered a different perspective; he wrote that the Kennedy campaign was desperate to win what was forecast to be a very close

election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operat ...

against

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

and

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. (July 5, 1902 – February 27, 1985) was an American diplomat and Republican United States senator from Massachusetts in both Senate seats in non-consecutive terms of service and a United States ambassador. He was considered ...

Johnson was needed on the ticket to help carry Texas and the

Southern states. Caro's research showed that on July 14, John Kennedy started the process while Johnson was still asleep. At 6:30 am, John Kennedy asked Robert Kennedy to prepare an estimate of upcoming electoral votes "including Texas".

[Caro 2012, pp. 121–135.] Robert called

Pierre Salinger

Pierre Emil George Salinger (June 14, 1925 – October 16, 2004) was an American journalist, author and politician. He served as the ninth press secretary for United States Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. Salinger served ...

and

Kenneth O'Donnell to assist him. Salinger realized the ramifications of counting Texas votes as their own and asked him whether he was considering a Kennedy–Johnson ticket, and Robert replied "yes".

Caro contends that it was then that John Kennedy called Johnson to arrange a meeting; he also called Pennsylvania governor

David L. Lawrence

David Leo Lawrence (June 18, 1889 – November 21, 1966) was an American politician who served as the 37th governor of Pennsylvania from 1959 to 1963. The first Catholic elected as governor, Lawrence is the only mayor of Pittsburgh to have ...

, a Johnson backer, to request that he nominate Johnson for vice president if Johnson were to accept the role. According to Caro, Kennedy and Johnson met and Johnson said that Kennedy would have trouble with Kennedy supporters who were anti-Johnson. Kennedy returned to his suite to announce the Kennedy–Johnson ticket to his closest supporters, including northern political bosses. O'Donnell was angry at what he considered a betrayal by Kennedy, who had previously cast Johnson as anti-labor and anti-liberal. Afterward, Robert Kennedy visited labor leaders who were extremely unhappy with the choice of Johnson and, after seeing the depth of labor opposition to Johnson, Robert ran messages between the hotel suites of his brother and Johnson—apparently trying to undermine the proposed ticket without John Kennedy's authorization.

Caro continues in his analysis that Robert Kennedy tried to get Johnson to agree to be the Democratic Party chairman rather than the vice president. Johnson refused to accept a change in plans unless it came directly from John Kennedy. Despite his brother's interference, John Kennedy was firm that Johnson was who he wanted as running mate; he met with staffers such as

Larry O'Brien

Lawrence Francis O'Brien Jr. (July 7, 1917September 28, 1990) was an American politician and basketball commissioner. He was one of the United States Democratic Party's leading electoral strategists for more than two decades. He served as Pos ...

, his national campaign manager, to say that Johnson was to be vice president. O'Brien recalled later that John Kennedy's words were wholly unexpected, but that after a brief consideration of the electoral vote situation, he thought "it was a stroke of genius".

When John and Robert Kennedy next saw their father

Joe Kennedy, he told them that signing Johnson as running mate was the smartest thing they had ever done.

Another account of how Johnson's nomination came about was told by

Evelyn Lincoln, JFK's secretary (both before and during his presidency). In 1993, in a videotaped interview, she described how the decision was made, stating she was the only witness to a private meeting between John and Robert Kennedy in a suite at the

Biltmore Hotel where they made the decision. She said she went in and out of the room as they spoke and, while she was in the room, heard them say that Johnson had tried to blackmail JFK into offering him the vice-presidential nomination with evidence of his

womanizing

Promiscuity is the practice of engaging in sexual activity frequently with different partners or being indiscriminate in the choice of sexual partners. The term can carry a moral judgment. A common example of behavior viewed as promiscuous by man ...

provided by FBI director

J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation ...

. She also overheard them discuss possible ways to avoid making the offer, and ultimately conclude that JFK had no choice.

Re-election to U.S. Senate

At the same time as his vice presidential run, Johnson also sought a third term in the U.S. Senate. According to Robert Caro, "On November 8, 1960, Lyndon Johnson won an election for both the vice presidency of the United States, on the Kennedy–Johnson ticket, and for a third term as senator (he had Texas law changed to allow him to run for both offices). When he won the vice presidency, he made arrangements to resign from the Senate, as he was required to do under federal law, as soon as it convened on January 3, 1961." In 1988,

Lloyd Bentsen

Lloyd Millard Bentsen Jr. (February 11, 1921 – May 23, 2006) was an American politician who was a four-term United States Senator (1971–1993) from Texas and the Democratic Party nominee for vice president in 1988 on the Michael Dukakis t ...

, the vice presidential running mate of Democratic presidential candidate

Michael Dukakis

Michael Stanley Dukakis (; born November 3, 1933) is an American retired lawyer and politician who served as governor of Massachusetts from 1975 to 1979 and again from 1983 to 1991. He is the longest-serving governor in Massachusetts history ...

, and a senator from Texas, took advantage of "Lyndon's law", and was able to retain his seat in the Senate despite Dukakis's loss to

George H. W. Bush.

Johnson was re-elected senator with 1,306,605 votes (58 percent) to Republican

John Tower's 927,653 (41.1 percent). Fellow Democrat

William A. Blakley

William Arvis "Dollar Bill" Blakley (November 17, 1898 – January 5, 1976) was an American politician and businessman from the state of Texas. Blakley was part of the conservative wing of the Texas Democratic Party. He served twice as an interim ...

was appointed to replace Johnson as senator, but Blakley lost a

special election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

in May 1961 to Tower.

Vice presidency (1961–1963)

After the election, Johnson was quite concerned about the traditionally ineffective nature of his new office and set about to assume authority not allotted to the position. He initially sought a transfer of the authority of Senate majority leader to the vice presidency, since that office made him president of the Senate, but faced vehement opposition from the Democratic Caucus, including members whom he had counted as his supporters.

Johnson sought to increase his influence within the executive branch. He drafted an executive order for Kennedy's signature, granting Johnson "general supervision" over matters of national security, and requiring all government agencies to "cooperate fully with the vice president in the carrying out of these assignments". Kennedy's response was to sign a non-binding letter requesting Johnson to "review" national security policies instead. Kennedy similarly turned down early requests from Johnson to be given an office adjacent to the Oval Office and to employ a full-time Vice Presidential staff within the White House. His lack of influence was thrown into relief later in 1961 when Kennedy appointed Johnson's friend

Sarah T. Hughes

Sarah Tilghman Hughes (August 2, 1896 – April 23, 1985) was an American lawyer and federal judge who served on the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas. She is best known as the judge who swore in Lyndon B. Johnson as ...

to a federal judgeship, whereas Johnson had tried and failed to garner the nomination for Hughes at the beginning of his vice presidency.

House Speaker Sam Rayburn

Samuel Taliaferro Rayburn (January 6, 1882 – November 16, 1961) was an American politician who served as the 43rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was a three-time House speaker, former House majority leader, two-time ...

wrangled the appointment from Kennedy in exchange for support of an administration bill.

Moreover, many members of the Kennedy White House were contemptuous of Johnson, including the president's brother,

Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

Robert F. Kennedy, and they ridiculed his comparatively brusque, crude manner. Congressman

Tip O'Neill

Thomas Phillip "Tip" O'Neill Jr. (December 9, 1912 – January 5, 1994) was an American politician who served as the 47th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1977 to 1987, representing northern Boston, Massachusetts, as ...

recalled that the Kennedy men "had a disdain for Johnson that they didn't even try to hide.... They actually took pride in snubbing him."

Kennedy, however, made efforts to keep Johnson busy, informed, and at the White House often, telling aides, "I can't afford to have my vice president, who knows every reporter in Washington, going around saying we're all screwed up, so we're going to keep him happy." Kennedy appointed him to jobs such as the head of the President's Committee on

Equal Employment Opportunities, through which he worked with African Americans and other minorities. Kennedy may have intended this to remain a more nominal position, but

Taylor Branch contends in ''Pillar of Fire'' that Johnson pushed the Kennedy administration's actions further and faster for civil rights than Kennedy originally intended to go. Branch notes the irony of Johnson being the advocate for

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

when the Kennedy family had hoped that he would appeal to conservative southern voters. In particular, he notes Johnson's

Memorial Day

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who have fought and died while serving in the United States armed forces. It is observed on the last Monda ...

1963 speech at

Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Gettysburg (; non-locally ) is a borough and the county seat of Adams County in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. The Battle of Gettysburg (1863) and President Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address are named for this town.

Gettysburg is home to ...

, as being a catalyst that led to more action.

Johnson took on numerous minor diplomatic missions, which gave him some insights into global issues, as well as opportunities for self-promotion in the name of showing the country's flag. During his visit to West Berlin on August 19–20, 1961, Johnson calmed Berliners who were outraged by the building of the Berlin Wall. He also attended Cabinet and

National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a n ...

meetings. Kennedy gave Johnson control over all presidential appointments involving Texas, and appointed him chairman of the President's Ad Hoc Committee for Science.

Kennedy also appointed Johnson Chairman of the

National Aeronautics and Space Council. The Soviets beat the United States with

the first manned spaceflight in April 1961, and Kennedy gave Johnson the task of evaluating the state of the U.S. space program and recommending a project that would allow the United States to catch up or beat the Soviets. Johnson responded with a recommendation that the United States gain the leadership role by committing the resources to embark on a

project to land an American on the Moon in the 1960s.

[Johnson to Kennedy]

"Evaluation of Space Program"

April 28, 1961. Kennedy assigned priority to the space program, but Johnson's appointment provided potential cover in case of a failure.

Johnson was touched by a Senate scandal in August 1963 when

Bobby Baker

Robert Gene Baker (November 12, 1928 – November 12, 2017) was an American political adviser to Lyndon B. Johnson, and an organizer for the Democratic Party. He became the Senate's Secretary to the Majority Leader. In 1963, he resigned during a ...

, the Secretary to the Majority Leader of the Senate and a protégé of Johnson's, came under investigation by the

Senate Rules Committee for allegations of bribery and financial malfeasance. One witness alleged that Baker had arranged for the witness to give kickbacks for the Vice President. Baker resigned in October, and the investigation did not expand to Johnson. The negative publicity from the affair fed rumors in Washington circles that Kennedy was planning on dropping Johnson from the Democratic ticket in the upcoming 1964 presidential election. However, on October 31, 1963, a reporter asked if he intended and expected to have Johnson on the ticket the following year. Kennedy replied, "Yes to both those questions." There is little doubt that Robert Kennedy and Johnson hated each other, yet John and Robert Kennedy agreed that dropping Johnson from the ticket could produce heavy losses in the South in the 1964 election, and they agreed that Johnson would stay on the ticket.

Presidency (1963–1969)

Johnson assumed the presidency amid a healthy economy with steady growth and low unemployment, and with no serious international crises. Therefore, he focused his attention on domestic policy, until escalation of the Vietnam War began in August 1964.

Succession

Johnson was quickly sworn in as president on ''

Air Force One

Air Force One is the official air traffic control designated call sign for a United States Air Force aircraft carrying the president of the United States. In common parlance, the term is used to denote U.S. Air Force aircraft modified and us ...

'' in Dallas on November 22, 1963, just two hours and eight minutes after

John F. Kennedy was assassinated, amid suspicions of a conspiracy against the government. He was sworn in by U.S. District Judge

Sarah T. Hughes

Sarah Tilghman Hughes (August 2, 1896 – April 23, 1985) was an American lawyer and federal judge who served on the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas. She is best known as the judge who swore in Lyndon B. Johnson as ...

, a family friend. In the rush, Johnson took the oath of office using a Roman Catholic

missal

A missal is a liturgical book containing instructions and texts necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the liturgical year. Versions differ across liturgical tradition, period, and purpose, with some missals intended to enable a prie ...

from President Kennedy's desk, despite not being Catholic,

due to the missal being mistaken for a Bible.

Cecil Stoughton

Cecil William Stoughton (January 18, 1920 – November 3, 2008) was an American photographer. He is best known for being President John F. Kennedy's photographer during his White House years.

Stoughton was present at the motorcade at which Kenne ...

's iconic photograph of Johnson taking the presidential oath of office as Mrs. Kennedy looks on is the most famous photo ever taken aboard a presidential aircraft.

Johnson was convinced of the need to make an impression of an immediate transition of power after the assassination to provide stability to a grieving nation in shock. He and the Secret Service were concerned that he could also be a target of a conspiracy,

and felt compelled to rapidly remove the new president from Dallas and return him to Washington.

This was greeted by some with assertions that Johnson was in too much haste to assume power.

On November 27, 1963, the new president delivered his

Let Us Continue speech to a joint session of Congress, saying that "No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy's memory than the earliest possible passage of the Civil Rights Bill for which he fought so long." The wave of national grief following the assassination gave enormous momentum to Johnson's promise to carry out Kennedy's plans and his policy of seizing Kennedy's legacy to give momentum to his legislative agenda.

On November 29, 1963, just one week after Kennedy's assassination, Johnson issued an executive order to rename NASA's

Apollo Launch Operations Center and the NASA/Air Force

Cape Canaveral launch facilities as the John F. Kennedy Space Center.

Cape Canaveral

, image = cape canaveral.jpg

, image_size = 300

, caption = View of Cape Canaveral from space in 1991

, map = Florida#USA

, map_width = 300

, type = Cape

, map_caption = Location in Florida

, location ...

was officially known as Cape Kennedy from 1963 until 1973.

Also on November 29, Johnson established a panel headed by Chief Justice

Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presided over a major shift in American constitutio ...

, known as the

Warren Commission

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known unofficially as the Warren Commission, was established by President Lyndon B. Johnson through on November 29, 1963, to investigate the assassination of United States P ...

, through

executive order

In the United States, an executive order is a directive by the president of the United States that manages operations of the federal government. The legal or constitutional basis for executive orders has multiple sources. Article Two of t ...

to investigate Kennedy's assassination and surrounding conspiracies. The commission conducted extensive research and hearings and unanimously concluded that

Lee Harvey Oswald

Lee Harvey Oswald (October 18, 1939 – November 24, 1963) was a U.S. Marine veteran who assassinated John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, on November 22, 1963.

Oswald was placed in juvenile detention at the age of 12 fo ...