Luther Burbank on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Luther Burbank (March 7, 1849 – April 11, 1926) was an American

Luther Burbank (March 7, 1849 – April 11, 1926) was an American

In Santa Rosa, Burbank purchased a plot of land, and established a

In Santa Rosa, Burbank purchased a plot of land, and established a  Gastrointestinal complications and violent hiccups weakened Luther in the last two weeks before his death, which was ultimately caused by heart failure. At his bedside were Elizabeth (his wife) and his sister when he died on April 11, 1926. The famous botanist was buried in an unmarked grave, under a giant Cedar of Lebanon at the Luther Burbank Home and Gardens in Santa Rosa, California. The tree in the photo no longer stands.

As Burbank's life drew to a close, the question arose as to who would carry on his work, and naturally there were many interested in doing so. Before his death in April 1926, Luther Burbank spoke quietly to his wife, and said:

"If anything happens to me, you will have to dispose of the business and the work, because you can't go on with it. There aren't a dozen organizations in the world that are equipped to go forward with it; of them all, there is really only one I think of that could make the most of it."

He named Stark Bro's Nurseries & Orchards Co. to carry on the work. Considerable argument has been spent upon whether the plants were technically willed to Stark Bro's; they were not. He left everything to Elizabeth: money, personal property, real estate, dozens of municipal utility bonds — and the plants and precious seeds. Elizabeth had first approached both Stanford and Berkeley to have either or both universities take over the experimental farm, but sold to Stark when those proffers didn't materialize. Mrs. Burbank entered into an agreement with Stark Bro's on August 23, 1927 to take the material they wanted from Burbank's properties. The contract included ownership of the business name and all of the customer information. A September 6, 1927 contract provided exclusive rights to sell uncompleted experiments with fruits at Sebastopol (except the Royal and Paradox) for 10 years. Stark Bro's had right of renewal. Tax receipts indicate payments of $27,000 to Mrs. Burbank. Exciting new kinds of fruits and flowers Burbank had developed (but never marketed) included 120 types of plums, 18 peaches, 28 apples, 500 hybrid roses, 30 cherries, 34 pears, 52 gladioli and many more. Stark Bro's subsequently introduced many of these varieties of their catalog.

Gastrointestinal complications and violent hiccups weakened Luther in the last two weeks before his death, which was ultimately caused by heart failure. At his bedside were Elizabeth (his wife) and his sister when he died on April 11, 1926. The famous botanist was buried in an unmarked grave, under a giant Cedar of Lebanon at the Luther Burbank Home and Gardens in Santa Rosa, California. The tree in the photo no longer stands.

As Burbank's life drew to a close, the question arose as to who would carry on his work, and naturally there were many interested in doing so. Before his death in April 1926, Luther Burbank spoke quietly to his wife, and said:

"If anything happens to me, you will have to dispose of the business and the work, because you can't go on with it. There aren't a dozen organizations in the world that are equipped to go forward with it; of them all, there is really only one I think of that could make the most of it."

He named Stark Bro's Nurseries & Orchards Co. to carry on the work. Considerable argument has been spent upon whether the plants were technically willed to Stark Bro's; they were not. He left everything to Elizabeth: money, personal property, real estate, dozens of municipal utility bonds — and the plants and precious seeds. Elizabeth had first approached both Stanford and Berkeley to have either or both universities take over the experimental farm, but sold to Stark when those proffers didn't materialize. Mrs. Burbank entered into an agreement with Stark Bro's on August 23, 1927 to take the material they wanted from Burbank's properties. The contract included ownership of the business name and all of the customer information. A September 6, 1927 contract provided exclusive rights to sell uncompleted experiments with fruits at Sebastopol (except the Royal and Paradox) for 10 years. Stark Bro's had right of renewal. Tax receipts indicate payments of $27,000 to Mrs. Burbank. Exciting new kinds of fruits and flowers Burbank had developed (but never marketed) included 120 types of plums, 18 peaches, 28 apples, 500 hybrid roses, 30 cherries, 34 pears, 52 gladioli and many more. Stark Bro's subsequently introduced many of these varieties of their catalog.

Until 1931, the Experiment Farm fell into some disrepair, so Stark Bro's sent emissaries to retrieve the most promising fruit, nut and ornamental shrubs, and in 1931 sold the flowers, vegetables and seeds to Burpee Seed Co. J. B. Keil came from Stark Bro's to coordinate the efforts and worked there from 1931 to 1934. Over the following years, Elizabeth worked with the Stark brothers to patent 16 Burbank fruits and flowers. The patents name Luther Burbank, deceased, as "inventor" by Elizabeth Waters Burbank, executrix of his estate. In 1935, Stark ended the agreement with Mrs. Burbank (or vice versa).

Mrs. Burbank then dispersed the majority of the gardens for subdivision. She sold the remaining property (excluding the house and greenhouse) to the Santa Rosa Junior College for use as a training ground. This lasted until 1954 (J. B. Keil stayed on as the caretaker). Twenty years later, the City took over ownership of the property (which it retains today as a free public showplace). The gardens include a thornless rose, spineless cactus, rainbow corn, a hybrid mulberry tree (which Luther hoped would spark an American silk industry) and his red combustion plant (Euonymus alatus).

Until 1931, the Experiment Farm fell into some disrepair, so Stark Bro's sent emissaries to retrieve the most promising fruit, nut and ornamental shrubs, and in 1931 sold the flowers, vegetables and seeds to Burpee Seed Co. J. B. Keil came from Stark Bro's to coordinate the efforts and worked there from 1931 to 1934. Over the following years, Elizabeth worked with the Stark brothers to patent 16 Burbank fruits and flowers. The patents name Luther Burbank, deceased, as "inventor" by Elizabeth Waters Burbank, executrix of his estate. In 1935, Stark ended the agreement with Mrs. Burbank (or vice versa).

Mrs. Burbank then dispersed the majority of the gardens for subdivision. She sold the remaining property (excluding the house and greenhouse) to the Santa Rosa Junior College for use as a training ground. This lasted until 1954 (J. B. Keil stayed on as the caretaker). Twenty years later, the City took over ownership of the property (which it retains today as a free public showplace). The gardens include a thornless rose, spineless cactus, rainbow corn, a hybrid mulberry tree (which Luther hoped would spark an American silk industry) and his red combustion plant (Euonymus alatus).

Burbank created hundreds of new varieties of fruits (plum, pear, prune, peach, blackberry, raspberry); potato, tomato; ornamental flowers and other plants. He introduced over 800 new plants, including flowers, grains, grasses, vegetables, cacti, and fruits.

; Fruits

; Grains, grasses, forage

*9 types

; Vegetables

*26 types

; Ornamentals

*91 types

On paper his method seems simple, but in practice it was extremely difficult. Most of the time, he would grow 10,000 or more plants of one variety, from which he selected as many as 50 seedlings or as few as one. From the selected plant or plants, he grew another 10,000 seedlings, continuing selective process until he produced the results he wanted. When he started his work, chestnut trees took 25 years to bear fruit. From his efforts, chestnut trees produced fruit after three years. A white blackberry so clear to see the seeds inside, a juicy and large plum which is still considered one of the finest in the world, a spineless cactus, a calla lily with fragrant odour was amongst his many creations.

Burbank created hundreds of new varieties of fruits (plum, pear, prune, peach, blackberry, raspberry); potato, tomato; ornamental flowers and other plants. He introduced over 800 new plants, including flowers, grains, grasses, vegetables, cacti, and fruits.

; Fruits

; Grains, grasses, forage

*9 types

; Vegetables

*26 types

; Ornamentals

*91 types

On paper his method seems simple, but in practice it was extremely difficult. Most of the time, he would grow 10,000 or more plants of one variety, from which he selected as many as 50 seedlings or as few as one. From the selected plant or plants, he grew another 10,000 seedlings, continuing selective process until he produced the results he wanted. When he started his work, chestnut trees took 25 years to bear fruit. From his efforts, chestnut trees produced fruit after three years. A white blackberry so clear to see the seeds inside, a juicy and large plum which is still considered one of the finest in the world, a spineless cactus, a calla lily with fragrant odour was amongst his many creations.

Burbank was praised and admired not only for his gardening skills but for his modesty, generosity and kind spirit.Smith, Jane S. "Prologue." The Garden of Invention: Luther Burbank and the Business of Breeding Plants. New York: Penguin, 2009. Print. He was very interested in education and gave money to the local schools.

He married twice: to Helen Coleman in 1890, which ended in divorce in 1896; and to Elizabeth Waters in 1916. He had no children.

In a speech given to the First

Burbank was praised and admired not only for his gardening skills but for his modesty, generosity and kind spirit.Smith, Jane S. "Prologue." The Garden of Invention: Luther Burbank and the Business of Breeding Plants. New York: Penguin, 2009. Print. He was very interested in education and gave money to the local schools.

He married twice: to Helen Coleman in 1890, which ended in divorce in 1896; and to Elizabeth Waters in 1916. He had no children.

In a speech given to the First

"The Training of the Human Plant"

Century Magazine, May 1907. * *Burbank, Luther. ''The Canna and the Calla: and some interesting work with striking results''. Paperback *Burbank, Luther with Wilbur Hall, ''Harvest of the Years''. This is Luther Burbank's autobiography published after his death in 1926. *Burbank, Luther. 1939.''An Architect of Nature''. Same details as ref. above, publisher: Watts & Co. (London) 'The Thinker's Library, No.76' *Burt, Olive W. ''Luther Burbank, Boy Wizard''. Biography published by Bobbs-Merrill in 1948 aimed at intermediate level students. *Anderson, N. O., & Olsen, R. T. (2015)

''A vast array of beauty: The accomplishments of the father of American ornamental plant breeding, Luther Burbank.''

HortScience, 50(2), 161-188. *Dreyer, Peter, ''A Gardener Touched With Genius The Life of Luther Burbank'', # L. Burbank Home & Gardens; New & expanded edition (January 1993), *Kraft, K. ''Luther Burbank, the Wizard and the Man''. New York : Meredith Press, 1967 ASIN: B0006BQE6C *Pandora, Katherine. "Luther Burbank". American National Biography. Retrieved on 2006-11-16. *Yogananda, Paramahansa. ''Autobiography of a Yogi''. Los Angeles : Self-Realization Fellowship, 1946 * *Tuomey, Honoria

Burbank, Scientist''."

Out West magazine, September 1905. pages 201-222. illustrated.

A complete bibliography of books by and about Luther Burbank on WorldCat.Luther Burbank Home and Gardens official websiteNational Inventors Hall of Fame profile

*

Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries and Their Practical Application

', 1914-1915, a 12-volume monographic series, is available online through the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center.

Luther Burbank Online

2013 — Selections from "Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries and Their Practical Application," 1914-1915, by an amateur gardener, 2013. *http://www.wschsgrf.org Official website of the Western Sonoma County Historical Society and Luther Burbank's Gold Ridge Experiment Farm *''Burbank Steps Forward with a Super-Wheat'',

scanned by Google Books

* * *

Luther Burbank materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)selected readings of Luther Burbank writings

* *Preece, John E. and Gale McGranahan

Luther Burbank’s Contributions to Walnuts

" ''HortScience'', Vol. 50:2, Feb. 2015, pp. 201–204. — Video slide presentation narrated by John E. Preece:

Luther Burbank's Contributions to Walnuts

" posted by cevizbiz cevizbiz, YouTube, November 14, 2015. {{DEFAULTSORT:Burbank, Luther 1849 births 1926 deaths American botanists American horticulturists American Unitarians Devotees of Paramahansa Yogananda History of Sonoma County, California People from Santa Rosa, California People from Lancaster, Massachusetts People from Sebastopol, California Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees American eugenicists

Luther Burbank (March 7, 1849 – April 11, 1926) was an American

Luther Burbank (March 7, 1849 – April 11, 1926) was an American botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

, horticulturist

Horticulture is the branch of agriculture that deals with the art, science, technology, and business of plant cultivation. It includes the cultivation of fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, herbs, sprouts, mushrooms, algae, flowers, seaweeds and no ...

and pioneer in agricultural science

Agricultural science (or agriscience for short) is a broad multidisciplinary field of biology that encompasses the parts of exact, natural, economic and social sciences that are used in the practice and understanding of agriculture. Profession ...

.

He developed more than 800 strains and varieties

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

of plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae exclud ...

s over his 55-year career. Burbank's varied creations included fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in particu ...

s, flower

A flower, sometimes known as a bloom or blossom, is the reproductive structure found in flowering plants (plants of the division Angiospermae). The biological function of a flower is to facilitate reproduction, usually by providing a mechani ...

s, grain

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit (caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legum ...

s, grass

Poaceae () or Gramineae () is a large and nearly ubiquitous family of monocotyledonous flowering plants commonly known as grasses. It includes the cereal grasses, bamboos and the grasses of natural grassland and species cultivated in lawns an ...

es, and vegetable

Vegetables are parts of plants that are consumed by humans or other animals as food. The original meaning is still commonly used and is applied to plants collectively to refer to all edible plant matter, including the flowers, fruits, stems, ...

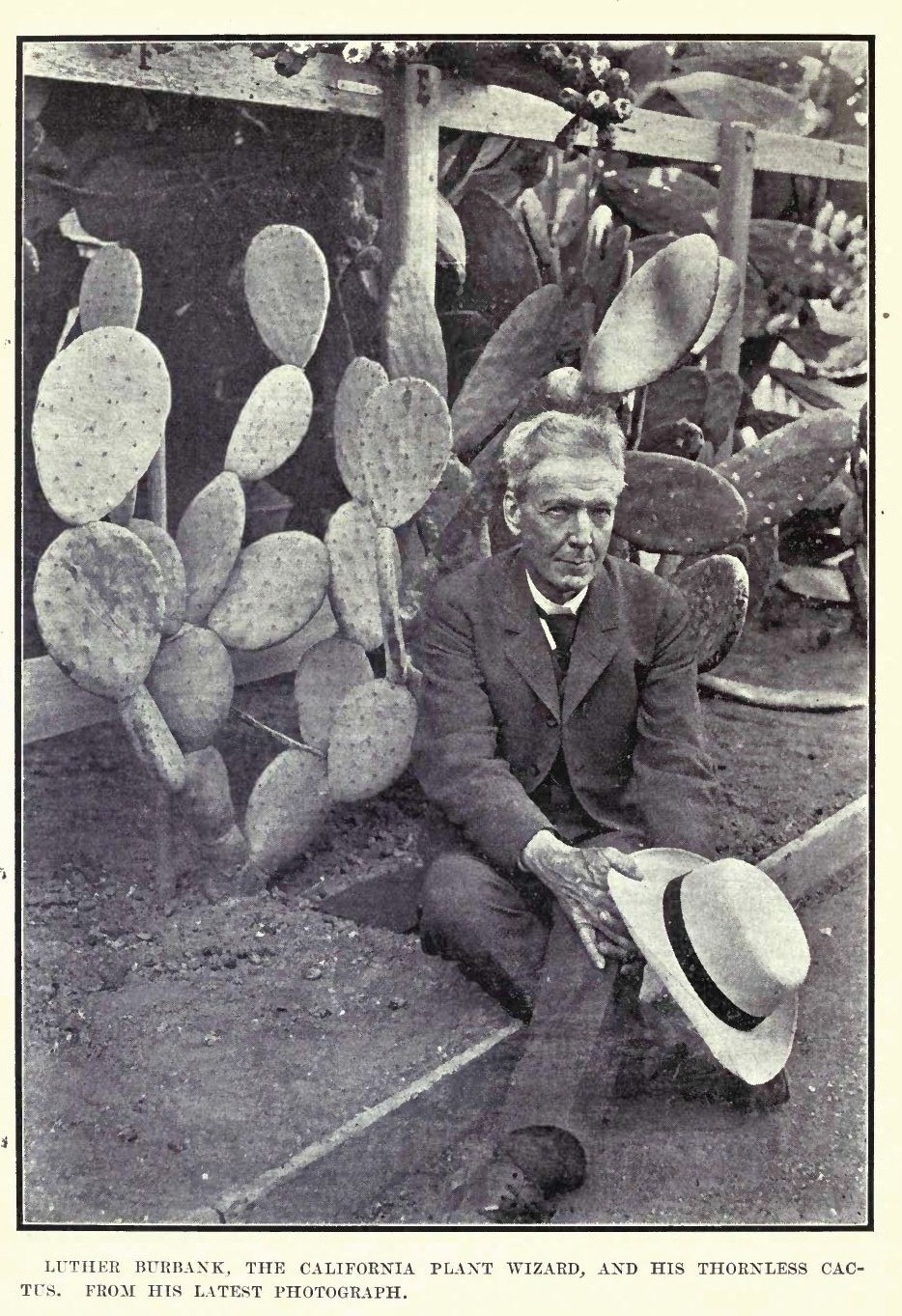

s. He developed (but did not create) a spineless cactus

A cactus (, or less commonly, cactus) is a member of the plant family Cactaceae, a family comprising about 127 genera with some 1750 known species of the order Caryophyllales. The word ''cactus'' derives, through Latin, from the Ancient Greek ...

(useful for cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult mal ...

-feed) and the plumcot

Pluots, apriums, apriplums, plumcots or pluclots are some of the Hybrid (biology), hybrids between different ''Prunus'' species that are also called interspecific plums. Whereas plumcots and apriplums are first-generation hybrids between a plum pa ...

.

Burbank's most successful strains and varieties included the Shasta daisy, the fire poppy (note possible confusion with the California wildflower, '' Papaver californicum'', which is also called a fire poppy), the "July Elberta" peach

The peach (''Prunus persica'') is a deciduous tree first domesticated and cultivated in Zhejiang province of Eastern China. It bears edible juicy fruits with various characteristics, most called peaches and others (the glossy-skinned, non-fu ...

, the "Santa Rosa" plum

A plum is a fruit of some species in ''Prunus'' subg. ''Prunus'.'' Dried plums are called prunes.

History

Plums may have been one of the first fruits domesticated by humans. Three of the most abundantly cultivated species are not found i ...

, the "Flaming Gold" nectarine

The peach (''Prunus persica'') is a deciduous tree first domesticated and cultivated in Zhejiang province of Eastern China. It bears edible juicy fruits with various characteristics, most called peaches and others (the glossy-skinned, non-fuz ...

, the "Wickson" plum

A plum is a fruit of some species in ''Prunus'' subg. ''Prunus'.'' Dried plums are called prunes.

History

Plums may have been one of the first fruits domesticated by humans. Three of the most abundantly cultivated species are not found i ...

(named after the agronomist Edward J. Wickson), the freestone peach, and the white blackberry

The white blackberry is an unusual white variety of blackberry developed by plant breeder Luther Burbank,Luther Burbank also known as the iceberg white blackberry or snowbank berry, probably originating as a pun on the name "Burbank".

He origi ...

. A natural genetic variant of the Burbank potato with russet-colored skin later became known as the russet Burbank potato

Russet Burbank is a potato cultivar with dark brown skin and few eyes that is the most widely grown potato in North America. A russet type, its flesh is white, dry, and mealy, and it is good for baking, mashing, and french fries (chips). It is a ...

. This large, brown-skinned, white-fleshed potato has become the world's predominant potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

in food processing

Food processing is the transformation of agricultural products into food, or of one form of food into other forms. Food processing includes many forms of processing foods, from grinding grain to make raw flour to home cooking to complex industr ...

. The Russet Burbank potato was in fact invented to help with the devastating situation in Ireland following the Great Famine. This particular potato variety was created by Burbank to help "revive the country's leading crop" as it is slightly late blight-resistant. Late blight

''Phytophthora infestans'' is an oomycete or water mold, a fungus-like microorganism that causes the serious potato and tomato disease known as late blight or potato blight. Early blight, caused by ''Alternaria solani'', is also often called "pot ...

is a disease that spread and destroyed potatoes all across Europe, but caused extreme chaos in Ireland due to the high dependency on potatoes as a crop by the Irish.

Life and work

Born inLancaster, Massachusetts

Lancaster is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, in the United States. Incorporated in 1653, Lancaster is the oldest town in Worcester County. As of the 2020 census, the town population was 8,441.

History

In 1643 Lancaster was first ...

, Burbank grew up on a farm and received only a high school education in Lancaster County Academy. The thirteenth of fifteen children, he enjoyed the plants in his mother's large garden. His father died when he was 18 years old, and Burbank used his inheritance to buy a 17-acre (69,000 m²) plot of land near Lunenburg center. There, he developed the Burbank potato. Burbank sold the rights to the Burbank potato for $150 and used the money to travel to Santa Rosa, California

Santa Rosa (Spanish language, Spanish for "Rose of Lima, Saint Rose") is a city and the county seat of Sonoma County, California, Sonoma County, in the North Bay (San Francisco Bay Area), North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, Bay Area ...

, in 1875. Later, a natural vegetative sport

Sport pertains to any form of Competition, competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and Skill, skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to specta ...

(that is, an aberrant growth that can be reproduced reliably in cultivation) of Burbank potato with russetted skin was selected and named Russet Burbank potato

Russet Burbank is a potato cultivar with dark brown skin and few eyes that is the most widely grown potato in North America. A russet type, its flesh is white, dry, and mealy, and it is good for baking, mashing, and french fries (chips). It is a ...

. Today, the Russet Burbank potato is the most widely cultivated potato in the United States. The potato is popular because it doesn’t expire as easily as other types of potatoes. A large percentage of McDonald's

McDonald's Corporation is an American Multinational corporation, multinational fast food chain store, chain, founded in 1940 as a restaurant operated by Richard and Maurice McDonald, in San Bernardino, California, United States. They rechri ...

french fries

French fries (North American English), chips (British English), finger chips ( Indian English), french-fried potatoes, or simply fries, are '' batonnet'' or ''allumette''-cut deep-fried potatoes of disputed origin from Belgium and France. Th ...

are made from this cultivar

A cultivar is a type of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue culture, ...

.

In Santa Rosa, Burbank purchased a plot of land, and established a

In Santa Rosa, Burbank purchased a plot of land, and established a greenhouse

A greenhouse (also called a glasshouse, or, if with sufficient heating, a hothouse) is a structure with walls and roof made chiefly of Transparent ceramics, transparent material, such as glass, in which plants requiring regulated climatic condit ...

, nursery, and experimental fields that he used to conduct crossbreeding

A crossbreed is an organism with purebred parents of two different breeds, varieties, or populations. ''Crossbreeding'', sometimes called "designer crossbreeding", is the process of breeding such an organism, While crossbreeding is used to main ...

experiments on plants, inspired by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

's ''The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication

''The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication'' is a book by Charles Darwin that was first published in January 1868.

A large proportion of the book contains detailed information on the domestication of animals and plants but it al ...

''. (This site is now open to the public as a city park, Luther Burbank Home and Gardens

Luther Burbank Home and Gardens is a city park containing the former home, greenhouse, gardens, and grave of noted American horticulturist Luther Burbank (1849-1926). It is located at the intersection of Santa Rosa Avenue and Sonoma Avenue in Sa ...

.) Later he purchased an plot of land in the nearby town of Sebastopol

Sevastopol (; uk, Севасто́поль, Sevastópolʹ, ; gkm, Σεβαστούπολις, Sevastoúpolis, ; crh, Акъя́р, Aqyár, ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea, and a major port on the Black Sea ...

, called Gold Ridge Farm.

Burbank became known through his plant catalogs, the most famous being 1893's "New Creations in Fruits and Flowers," and through the word of mouth of satisfied customers, as well as press reports that kept him in the news throughout the first decade of the century.

In that same year, Stark Bro's Nurseries & Orchards Co. discovered the 'Delicious' apple, an elongated fruit with five bumps on the calyx end. The oddly-shaped apple attracted the attention of Burbank, a famed grafter and budder of trees, plants and flowers. He called the new 'Delicious' variety "the finest-flavored apple in all the world." It was also in 1893 that the Starks began their storied cooperation with Luther Burbank and his fantastic new varieties of fruits.

Among those with the foresight to recognize the possibilities of Burbank's work was Clarence McDowell Stark, who went to California and sought Burbank out. After talking to him in Santa Rosa and seeing the results of his experiments, Clarence was convinced that Burbank was right, and his professorial critics were wrong. To Clarence's great dismay, he saw that Luther Burbank was operating a small seed and nursery business in an attempt to finance his experiments and provide himself a living. It was clear that he would never be able to realize his potential under these meager circumstances.

Clarence said to Burbank: "I don't think you will ever make a real success in the nursery business because your heart is not in it. But if you will carry forward the type of hybridizing you are doing, I think you will go very far in your chosen field. To demonstrate our sincere belief in your work, our company will give you $9,000 if you will let me pick three of these new fruits you have shown me.'"

Burbank often credited the Stark family with making his work profitable. In return, he later joined with Thomas Edison to support Paul Stark Sr. in his fight to get patent legislation passed for plant breeders. Along with Clarence's $9,000 worth of help, Luther also had something of a fan club — The Luther Burbank Society. The group took it upon themselves to publish his discoveries and manage his business affairs, affording him some additional means by which to live.

From 1904 through 1909, Burbank received several grants from the Carnegie Institution to support his ongoing research on hybridization. He was supported by the practical-minded Andrew Carnegie himself, over those of his advisers who objected that Burbank was not "scientific" in his methods.

Gastrointestinal complications and violent hiccups weakened Luther in the last two weeks before his death, which was ultimately caused by heart failure. At his bedside were Elizabeth (his wife) and his sister when he died on April 11, 1926. The famous botanist was buried in an unmarked grave, under a giant Cedar of Lebanon at the Luther Burbank Home and Gardens in Santa Rosa, California. The tree in the photo no longer stands.

As Burbank's life drew to a close, the question arose as to who would carry on his work, and naturally there were many interested in doing so. Before his death in April 1926, Luther Burbank spoke quietly to his wife, and said:

"If anything happens to me, you will have to dispose of the business and the work, because you can't go on with it. There aren't a dozen organizations in the world that are equipped to go forward with it; of them all, there is really only one I think of that could make the most of it."

He named Stark Bro's Nurseries & Orchards Co. to carry on the work. Considerable argument has been spent upon whether the plants were technically willed to Stark Bro's; they were not. He left everything to Elizabeth: money, personal property, real estate, dozens of municipal utility bonds — and the plants and precious seeds. Elizabeth had first approached both Stanford and Berkeley to have either or both universities take over the experimental farm, but sold to Stark when those proffers didn't materialize. Mrs. Burbank entered into an agreement with Stark Bro's on August 23, 1927 to take the material they wanted from Burbank's properties. The contract included ownership of the business name and all of the customer information. A September 6, 1927 contract provided exclusive rights to sell uncompleted experiments with fruits at Sebastopol (except the Royal and Paradox) for 10 years. Stark Bro's had right of renewal. Tax receipts indicate payments of $27,000 to Mrs. Burbank. Exciting new kinds of fruits and flowers Burbank had developed (but never marketed) included 120 types of plums, 18 peaches, 28 apples, 500 hybrid roses, 30 cherries, 34 pears, 52 gladioli and many more. Stark Bro's subsequently introduced many of these varieties of their catalog.

Gastrointestinal complications and violent hiccups weakened Luther in the last two weeks before his death, which was ultimately caused by heart failure. At his bedside were Elizabeth (his wife) and his sister when he died on April 11, 1926. The famous botanist was buried in an unmarked grave, under a giant Cedar of Lebanon at the Luther Burbank Home and Gardens in Santa Rosa, California. The tree in the photo no longer stands.

As Burbank's life drew to a close, the question arose as to who would carry on his work, and naturally there were many interested in doing so. Before his death in April 1926, Luther Burbank spoke quietly to his wife, and said:

"If anything happens to me, you will have to dispose of the business and the work, because you can't go on with it. There aren't a dozen organizations in the world that are equipped to go forward with it; of them all, there is really only one I think of that could make the most of it."

He named Stark Bro's Nurseries & Orchards Co. to carry on the work. Considerable argument has been spent upon whether the plants were technically willed to Stark Bro's; they were not. He left everything to Elizabeth: money, personal property, real estate, dozens of municipal utility bonds — and the plants and precious seeds. Elizabeth had first approached both Stanford and Berkeley to have either or both universities take over the experimental farm, but sold to Stark when those proffers didn't materialize. Mrs. Burbank entered into an agreement with Stark Bro's on August 23, 1927 to take the material they wanted from Burbank's properties. The contract included ownership of the business name and all of the customer information. A September 6, 1927 contract provided exclusive rights to sell uncompleted experiments with fruits at Sebastopol (except the Royal and Paradox) for 10 years. Stark Bro's had right of renewal. Tax receipts indicate payments of $27,000 to Mrs. Burbank. Exciting new kinds of fruits and flowers Burbank had developed (but never marketed) included 120 types of plums, 18 peaches, 28 apples, 500 hybrid roses, 30 cherries, 34 pears, 52 gladioli and many more. Stark Bro's subsequently introduced many of these varieties of their catalog.

Until 1931, the Experiment Farm fell into some disrepair, so Stark Bro's sent emissaries to retrieve the most promising fruit, nut and ornamental shrubs, and in 1931 sold the flowers, vegetables and seeds to Burpee Seed Co. J. B. Keil came from Stark Bro's to coordinate the efforts and worked there from 1931 to 1934. Over the following years, Elizabeth worked with the Stark brothers to patent 16 Burbank fruits and flowers. The patents name Luther Burbank, deceased, as "inventor" by Elizabeth Waters Burbank, executrix of his estate. In 1935, Stark ended the agreement with Mrs. Burbank (or vice versa).

Mrs. Burbank then dispersed the majority of the gardens for subdivision. She sold the remaining property (excluding the house and greenhouse) to the Santa Rosa Junior College for use as a training ground. This lasted until 1954 (J. B. Keil stayed on as the caretaker). Twenty years later, the City took over ownership of the property (which it retains today as a free public showplace). The gardens include a thornless rose, spineless cactus, rainbow corn, a hybrid mulberry tree (which Luther hoped would spark an American silk industry) and his red combustion plant (Euonymus alatus).

Until 1931, the Experiment Farm fell into some disrepair, so Stark Bro's sent emissaries to retrieve the most promising fruit, nut and ornamental shrubs, and in 1931 sold the flowers, vegetables and seeds to Burpee Seed Co. J. B. Keil came from Stark Bro's to coordinate the efforts and worked there from 1931 to 1934. Over the following years, Elizabeth worked with the Stark brothers to patent 16 Burbank fruits and flowers. The patents name Luther Burbank, deceased, as "inventor" by Elizabeth Waters Burbank, executrix of his estate. In 1935, Stark ended the agreement with Mrs. Burbank (or vice versa).

Mrs. Burbank then dispersed the majority of the gardens for subdivision. She sold the remaining property (excluding the house and greenhouse) to the Santa Rosa Junior College for use as a training ground. This lasted until 1954 (J. B. Keil stayed on as the caretaker). Twenty years later, the City took over ownership of the property (which it retains today as a free public showplace). The gardens include a thornless rose, spineless cactus, rainbow corn, a hybrid mulberry tree (which Luther hoped would spark an American silk industry) and his red combustion plant (Euonymus alatus).

Burbank cultivars

Burbank created hundreds of new varieties of fruits (plum, pear, prune, peach, blackberry, raspberry); potato, tomato; ornamental flowers and other plants. He introduced over 800 new plants, including flowers, grains, grasses, vegetables, cacti, and fruits.

; Fruits

; Grains, grasses, forage

*9 types

; Vegetables

*26 types

; Ornamentals

*91 types

On paper his method seems simple, but in practice it was extremely difficult. Most of the time, he would grow 10,000 or more plants of one variety, from which he selected as many as 50 seedlings or as few as one. From the selected plant or plants, he grew another 10,000 seedlings, continuing selective process until he produced the results he wanted. When he started his work, chestnut trees took 25 years to bear fruit. From his efforts, chestnut trees produced fruit after three years. A white blackberry so clear to see the seeds inside, a juicy and large plum which is still considered one of the finest in the world, a spineless cactus, a calla lily with fragrant odour was amongst his many creations.

Burbank created hundreds of new varieties of fruits (plum, pear, prune, peach, blackberry, raspberry); potato, tomato; ornamental flowers and other plants. He introduced over 800 new plants, including flowers, grains, grasses, vegetables, cacti, and fruits.

; Fruits

; Grains, grasses, forage

*9 types

; Vegetables

*26 types

; Ornamentals

*91 types

On paper his method seems simple, but in practice it was extremely difficult. Most of the time, he would grow 10,000 or more plants of one variety, from which he selected as many as 50 seedlings or as few as one. From the selected plant or plants, he grew another 10,000 seedlings, continuing selective process until he produced the results he wanted. When he started his work, chestnut trees took 25 years to bear fruit. From his efforts, chestnut trees produced fruit after three years. A white blackberry so clear to see the seeds inside, a juicy and large plum which is still considered one of the finest in the world, a spineless cactus, a calla lily with fragrant odour was amongst his many creations.

Publications

Burbank was criticized by scientists of his day because he did not keep the kind of careful records that are the norm in scientific research and because he was mainly interested in creating useful or targeted cultivars rather than in thebasic research

Basic research, also called pure research or fundamental research, is a type of scientific research with the aim of improving scientific theories for better understanding and prediction of natural or other phenomena. In contrast, applied resear ...

of understanding their biology or the mechanisms by which his artificial selection schemes achieved their results. Purdue University

Purdue University is a public land-grant research university in West Lafayette, Indiana, and the flagship campus of the Purdue University system. The university was founded in 1869 after Lafayette businessman John Purdue donated land and money ...

professor Jules Janick, writing in the 2004 ''World Book Encyclopedia

The ''World Book Encyclopedia'' is an American encyclopedia. The encyclopedia is designed to cover major areas of knowledge uniformly, but it shows particular strength in scientific, technical, historical and medical subjects. ''World Book'' wa ...

'', says: "Burbank cannot be considered a scientist in the academic sense."

Although Burbank may not have been a scientist by the standards of his peers, his lack of record keeping reflected the difficulties of developing and distributing cultivars in the era in which he lived. His innovations were revolutionary, and in a time when there was no way to legally protect one's inventions, Burbank may have been cautious with the successes he decided to document. Additionally, his records may not have been coherent (to the chagrin of modern scholars) because he felt his time was better valued in the garden, not writing each trial and error down in his record book.

In 1893, Burbank published a descriptive catalog of some of his best varieties, entitled ''New Creations in Fruits and Flowers''.

In 1907, Burbank published an "essay on childrearing", called ''The Training of the Human Plant''. In it, he advocated improved treatment of children, cultural homogenization and replacement in education, and management of reproduction and development in both a eugenic

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

and euthenic manner, though he does not directly reference either. His support for eugenic methods is couched in his horticultural methodology and he makes direct analogies between the two, comparing the population of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

to a massive outcrossing experiment:

During his career, Burbank wrote and co-wrote several books on his methods and results, including his eight-volume ''How Plants Are Trained to Work for Man'' (1921), ''Harvest of the Years'' (with Wilbur Hall, 1927), ''Partner of Nature'' (1939), and the 12-volume ''Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries and Their Practical Application''.

Methodology

Burbank experimented with a variety of techniques such as grafting, hybridization, and cross-breeding.Intraspecific breeding

Intraspecifichybrid

Hybrid may refer to:

Science

* Hybrid (biology), an offspring resulting from cross-breeding

** Hybrid grape, grape varieties produced by cross-breeding two ''Vitis'' species

** Hybridity, the property of a hybrid plant which is a union of two dif ...

ization within a plant species was demonstrated by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

and Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, Augustinians, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinians, Augustinian friar and abbot of St Thomas's Abbey, Brno, St. Thomas' Abbey in Br� ...

, and was further developed by geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic processe ...

s and plant breeders.

In 1908, George Harrison Shull

George Harrison Shull (April 15, 1874 – September 28, 1954) was an eminent American plant geneticist and the younger brother of botanical illustrator and plant breeder J. Marion Shull. He was born on a farm in Clark County, Ohio, graduated fr ...

described heterosis

Heterosis, hybrid vigor, or outbreeding enhancement is the improved or increased function of any biological quality in a hybrid offspring. An offspring is heterotic if its traits are enhanced as a result of mixing the genetic contributions of ...

, also known as hybrid vigor. Heterosis describes the tendency of the progeny of a specific cross to outperform both parents. The detection of the usefulness of heterosis for plant breeding has led to the development of inbred lines that reveal a heterotic yield advantage when they are crossed. Maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

was the first species where heterosis was widely used to produce hybrids.

By the 1920s, statistical

Statistics (from German: ''Statistik'', "description of a state, a country") is the discipline that concerns the collection, organization, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of data. In applying statistics to a scientific, industria ...

methods were developed to analyze gene action and distinguish heritable variation from variation caused by environment. In 1933, another important breeding technique, cytoplasmic male sterility

Cytoplasmic male sterility is total or partial male sterility in plants as the result of specific nuclear and mitochondrial interactions. Male sterility is the failure of plants to produce functional anthers, pollen, or male gametes.

Backgroun ...

(CMS), developed in maize, was described by Marcus Morton Rhoades

Marcus Morton Rhoades (July 24, 1903 in Graham, Missouri – December 30, 1991) was an American cytogeneticist.

Education

He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in 1927, a Master of Science degree in 1928 from the University of Michigan and a P ...

. CMS is a maternally inherited trait that makes the plant produce sterile pollen

Pollen is a powdery substance produced by seed plants. It consists of pollen grains (highly reduced microgametophytes), which produce male gametes (sperm cells). Pollen grains have a hard coat made of sporopollenin that protects the gametophyt ...

. This enables the production of hybrids without the need for labour-intensive detasseling Detasseling corn is removing the pollen-producing flowers, the tassel, from the tops of corn (maize) plants and placing them on the ground. It is a form of pollination control,United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

in the early 20th century. Similar yield increases were not produced elsewhere until after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the Green Revolution

The Green Revolution, also known as the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period of technology transfer initiatives that saw greatly increased crop yields and agricultural production. These changes in agriculture began in developed countrie ...

increased crop production in the developing world in the 1960s

File:1960s montage.png, Clockwise from top left: U.S. soldiers during the Vietnam War; the Beatles led the British Invasion of the U.S. music market; a half-a-million people participate in the 1969 Woodstock Festival; Neil Armstrong and Buzz ...

.

Eugenics

Along with breeding plants, Burbank believed human beings should be selectively bred, and he was active in theAmerican eugenics movement

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the Genetics, genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th c ...

and wrote in publications of the American Breeders' Association

The American Genetic Association (AGA) is a USA-based professional scientific organization dedicated to the study of genetics and genomics which was founded as the American Breeders' Association in 1903. The association has published the ''Journ ...

as an honorary member. He was also elected to the ABA's Committee on Eugenics in 1906. As a eugenicist

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

, he promoted genetic discrimination. In Burbank's book, ''The Training Of The Human Plant'' he wrote: This belief in the benefit of crossing human "species" and his staunch support for Lamarckian inheritance put him somewhat at odds with mainstream eugenic views of the time, which were in the majority strongly anti-miscegenation. His Lamarckian

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

belief in the inheritance of acquired characteristics informed his support for population improvement primarily by managing the environment of children over many generations, which aligned him also with the euthenics movement. He believed that environment played a crucial role in the development of children:

Classical plant breeding

Classical plant breeding uses deliberate interbreeding (''crossing'') of closely or distantly related individuals to produce new crop varieties or lines with desirable properties. Plants are crossbred to introduce traits/gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s from one variety or line into a new genetic background. For example, a mildew

Mildew is a form of fungus. It is distinguished from its closely related counterpart, mould, largely by its colour: moulds appear in shades of black, blue, red, and green, whereas mildew is white. It appears as a thin, superficial growth consi ...

-resistant pea

The pea is most commonly the small spherical seed or the seed-pod of the flowering plant species ''Pisum sativum''. Each pod contains several peas, which can be green or yellow. Botanically, pea pods are fruit, since they contain seeds and d ...

may be crossed with a high-yielding but susceptible pea, the goal of the cross being to introduce mildew resistance without losing the high-yield characteristics. Progeny from the cross would then be crossed with the high-yielding parent to ensure that the progeny were most like the high-yielding parent, (backcrossing

Backcrossing is a crossing of a hybrid with one of its parents or an individual genetically similar to its parent, to achieve offspring with a genetic identity closer to that of the parent. It is used in horticulture, animal breeding, and product ...

). The progeny from that cross would then be tested for yield and mildew resistance and high-yielding resistant plants would be further developed. Plants may also be crossed with themselves to produce ''inbred'' varieties for breeding.

Classical breeding relies largely on homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in cellular organisms but may ...

between chromosomes to generate genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

. The classical plant breeder may also make use of a number of ''in vitro'' techniques such as protoplast fusion, embryo rescue or mutagenesis (see below) to generate diversity and produce hybrid plants that would not exist in nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

.

Traits that breeders have tried to incorporate into crop plants in the last 100 years include:

# Increased quality

Quality may refer to:

Concepts

*Quality (business), the ''non-inferiority'' or ''superiority'' of something

*Quality (philosophy), an attribute or a property

*Quality (physics), in response theory

*Energy quality, used in various science discipli ...

and yield of the crop

# Increased tolerance of environmental pressures (salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal ...

, extreme temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various temperature scales that historically have relied o ...

, drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

)

# Resistance to virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es, fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

and bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

# Increased tolerance to insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three pairs ...

pests

# Increased tolerance of herbicide

Herbicides (, ), also commonly known as weedkillers, are substances used to control undesired plants, also known as weeds.EPA. February 201Pesticides Industry. Sales and Usage 2006 and 2007: Market Estimates. Summary in press releasMain page fo ...

s

Mass selection

Burbankcross-pollinated

Pollination is the transfer of pollen from an anther of a plant to the stigma of a plant, later enabling fertilisation and the production of seeds, most often by an animal or by wind. Pollinating agents can be animals such as insects, birds, a ...

the flowers of plants by hand and planted all the resulting seeds. He then selected the most promising plants to cross with other ones.

Personal life

Congregational Church

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

of San Francisco in 1926, Burbank said:

Luther Burbank was highly revered throughout the United States of America. In September 1905 a group of California's most influential businessmen, intellectuals, and politicians gathered at a banquet thrown in honor of Luther Burbank by the State Board of Trade. Many people spoke about Burbank, such as Senator Perkins who stated that Burbank could teach the government valuable lessons, and that "he is doing more to instruct, interest, and make popular the work in the garden than any man of his generation."

At the same convention, Albert G. Burnett, a judge of the Superior Court for Sonoma County

Sonoma County () is a county (United States), county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 United States Census, its population was 488,863. Its county seat and largest city is Santa Rosa, California, Santa Rosa. It is to the n ...

stated that Burbank had improved the community incredibly making it a place that people came "to sit at the feet of this great apostle and prophet of beauty and happiness ... and catch some measure of his matchless inspiration." He also stated that Burbank's deeds were always done to "bring more of the sunshine of comfort and happiness into the cottages of the poor as well as the palaces of the rich."

In 1924 Burbank wrote a letter endorsing the "Yogoda" training system of Paramahansa Yogananda

Paramahansa Yogananda (born Mukunda Lal Ghosh; January 5, 1893March 7, 1952) was an Indian Hindu monk, yogi and guru who introduced millions to the teachings of meditation and Kriya Yoga through his organization Self-Realization Fellows ...

as a superior alternative to what he considered narrowly intellectual education offered by most schools. He caused a great deal of public controversy a few months before his death in 1926 when he answered questions about his deepest beliefs by a reporter from the ''San Francisco Bulletin

The ''San Francisco Evening Bulletin'' was a newspaper in San Francisco, founded as the ''Daily Evening Bulletin'' in 1855 by James King of William. King used the newspaper to crusade against political corruption, and built it into having the highe ...

'' with the following statement:

Paramahansa Yogananda writes in Autobiography of a Yogi that "Intimate communion with Nature, who unlocked to him urbankmany of her jealously guarded secrets, had given Burbank a boundless spiritual reverence". Burbank had received Kriya Yoga initiation from Paramahansa Yogananda, and he is quoted as saying "I practice the technique devoutly, Swamiji...Sometimes I feel very close to the infinite power...then i have been able to heal sick persons around me, as well as many ailing plants". He is also recorded as saying the following in relation to his deceased mother "Many times since her death I have been blessed by her appearance in visions; she has spoken to me."

Death

In mid-March 1926, Burbank suffered a heart attack and became ill withgastrointestinal

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

complications. He died on April 11, 1926, aged 77, and is buried near the greenhouse at the Luther Burbank Home and Gardens

Luther Burbank Home and Gardens is a city park containing the former home, greenhouse, gardens, and grave of noted American horticulturist Luther Burbank (1849-1926). It is located at the intersection of Santa Rosa Avenue and Sonoma Avenue in Sa ...

. An address at the Memorial Service was given by Judge Ben Lindsey.

Legacy

California's Arbor Day was made March 7, Luther Burbank's birthday, in honor of him. Burt, Olive W., Luther Burbank, Boy Wizard, Bobbs-Merril Company, Inc., 1948, 1962, p. 180. Burbank's fame and admiration reflect the various ways people see humans' roles in nature, by representing both the importance of our connection to the natural world and the numerous possibilities created by plant manipulation. Burbank's work spurred the passing of the 1930Plant Patent Act

The Plant Patent Act of 1930 (enacted on 1930-06-17 as Title III of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff, ch. 497, , codified as 35 U.S.C.br>Ch. 15 is a United States federal law spurred by the work of Luther Burbank and the nursery industry. This piece of ...

four years after his death. The legislation made it possible to patent new varieties of plants (excluding tuber

Tubers are a type of enlarged structure used as storage organs for nutrients in some plants. They are used for the plant's perennation (survival of the winter or dry months), to provide energy and nutrients for regrowth during the next growing ...

-propagated plants). Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These inventio ...

testified before Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

in support of the legislation and said that "This ill ILL may refer to:

* ''I Love Lucy'', a landmark American television sitcom

* Illorsuit Heliport (location identifier: ILL), a heliport in Illorsuit, Greenland

* Institut Laue–Langevin, an internationally financed scientific facility

* Interlibrar ...

will, I feel sure, give us many Burbanks." The authorities issued Plant Patents #12, #13, #14, #15, #16, #18, #41, #65, #66, #235, #266, #267, #269, #290, #291, and #1041 to Burbank posthumously.

In 1931, while visiting San Francisco, Frida Kahlo

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country's popular culture, ...

painted a portrait of Burbank emerging as a tree from his interred corpse.

In 1940, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 3-cent stamp honoring Burbank.

In 1986, Burbank was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame

The National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) is an American not-for-profit organization, founded in 1973, which recognizes individual engineers and inventors who hold a U.S. patent of significant technology. Besides the Hall of Fame, it also opera ...

. The Luther Burbank Home and Gardens

Luther Burbank Home and Gardens is a city park containing the former home, greenhouse, gardens, and grave of noted American horticulturist Luther Burbank (1849-1926). It is located at the intersection of Santa Rosa Avenue and Sonoma Avenue in Sa ...

, in downtown Santa Rosa, are now designated as a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

. Luther Burbank's Gold Ridge Experiment Farm

Luther Burbank's Gold Ridge Experiment Farm is the official name of the that remain of the farm originally purchased in 1885 by famed plant breeder Luther Burbank (1849-1926) in an area of Sebastopol, California, Sebastopol, California, formerly ...

is listed in the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

a few miles west of Santa Rosa in the town of Sebastopol, California

Sebastopol ( ) is a city in Sonoma County, in California with a recorded population of 7,521, per the 2020 U.S. Census.

Sebastopol was once primarily a plum and apple-growing region. Today, wine grapes are the predominant agriculture crop, a ...

.

The home that Luther Burbank was born in, as well as his California garden office, were moved by Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

to Dearborn, Michigan

Dearborn is a city in Wayne County in the U.S. state of Michigan. At the 2020 census, it had a population of 109,976. Dearborn is the seventh most-populated city in Michigan and is home to the largest Muslim population in the United States pe ...

, and are part of Greenfield Village

The Henry Ford (also known as the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and Greenfield Village, and as the Edison Institute) is a history museum complex in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn, Michigan, United States. The museum collection contains ...

.

Several places and institution are named for Luther Burbank. They include:

* Luther Burbank Center for the Arts

The Luther Burbank Center for the Arts (sometimes called the LBC), and previously known as the Wells Fargo Center for the Arts from March 2005 to March 2016) is a performance venue located just north of Santa Rosa, California, near U.S. 101. The ...

, a large facility in Santa Rosa, California

Santa Rosa (Spanish language, Spanish for "Rose of Lima, Saint Rose") is a city and the county seat of Sonoma County, California, Sonoma County, in the North Bay (San Francisco Bay Area), North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, Bay Area ...

* Luther Burbank High School in Sacramento, California

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento C ...

* Luther Burbank High School in San Antonio, Texas

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_t ...

* The Luther Burbank School District in San Jose, California

San Jose, officially San José (; ; ), is a major city in the U.S. state of California that is the cultural, financial, and political center of Silicon Valley and largest city in Northern California by both population and area. With a 2020 popul ...

* Luther Burbank Middle School in Lancaster, Massachusetts

Lancaster is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, in the United States. Incorporated in 1653, Lancaster is the oldest town in Worcester County. As of the 2020 census, the town population was 8,441.

History

In 1643 Lancaster was first ...

* Luther Burbank Middle School in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Highland Park, California

Highland Park is a neighborhood in Los Angeles, California, located in the city's Northeast region. It was one of the first subdivisions of Los Angeles and is inhabited by a variety of ethnic and socioeconomic groups.

History

The area was set ...

(coincidentally a few miles from Burbank, California

Burbank is a city in the southeastern end of the San Fernando Valley in Los Angeles County, California, United States. Located northwest of downtown Los Angeles, Burbank has a population of 107,337. The city was named after David Burbank, w ...

, named for Dr. David Burbank, a 19th-century real estate developer.)

* Luther Burbank Elementary School in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at th ...

* Luther Burbank Elementary School in Santa Rosa, California

Santa Rosa (Spanish language, Spanish for "Rose of Lima, Saint Rose") is a city and the county seat of Sonoma County, California, Sonoma County, in the North Bay (San Francisco Bay Area), North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, Bay Area ...

* Luther Burbank Elementary School in Burbank, Illinois

Burbank is a city in Cook County, Illinois, United States. The population was 29,439 at the 2020 census. It is located at the southwest edge of the city of Chicago; the Chicago city limit – specifically that of the Ashburn neighborhood &nda ...

* Luther Burbank Elementary School in Long Beach, California

Long Beach is a city in Los Angeles County, California. It is the 42nd-most populous city in the United States, with a population of 466,742 as of 2020. A charter city, Long Beach is the seventh-most populous city in California.

Incorporate ...

* Luther Burbank Elementary School in Merced, California

Merced (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Mercy") is a city in, and the county seat of, Merced County, California, Merced County, California, United States, in the San Joaquin Valley. As of the 2020 Census, the city had a population of 86,333, up ...

*Burbank Elementary School in Modesto, California

Modesto () is the county seat and largest city of Stanislaus County, California, United States. With a population of 218,464 at the 2020 census, it is the 19th largest city in the state of California and forms part of the Sacramento-Stockton- ...

*Luther Burbank Park in Mercer Island, Washington

Mercer Island is a city in King County, Washington, United States, located on an island of the same name in the southern portion of Lake Washington. Mercer Island is in the Seattle metropolitan area, with Seattle to its west and Bellevue to i ...

* Burbank Elementary School in Artesia, California

Artesia (Spanish for "artesian aquifer") is a city in southeast Los Angeles County, California. Artesia was incorporated on May 29, 1959, and is one of Los Angeles County's Gateway Cities. The city has a 2010 census population of 16,522. Artesi ...

* The census-designated place Burbank, Washington

Burbank is a census-designated place (CDP) in Walla Walla County, Washington, United States, where the Snake River meets the Columbia. The population was 3,291 at the 2010 census. Named for Luther Burbank, the city is located just east of Pasc ...

* The census-designated place Burbank, Santa Clara County, CA

Burbank is a census-designated place in Santa Clara County, California. Part of the neighborhood has been annexed to San Jose, while the rest consists of unincorporated areas of Santa Clara County. The population was 4,926 at the 2010 census. The ...

* The census-designated place Burbank, Illinois

Burbank is a city in Cook County, Illinois, United States. The population was 29,439 at the 2020 census. It is located at the southwest edge of the city of Chicago; the Chicago city limit – specifically that of the Ashburn neighborhood &nda ...

* The census-designated place Burbank, Alabama

* Luther Burbank Savings, Santa Rosa

Santa Rosa is the Italian, Portuguese and Spanish name for Saint Rose.

Santa Rosa may also refer to:

Places Argentina

*Santa Rosa, Mendoza, a city

* Santa Rosa, Tinogasta, Catamarca

* Santa Rosa, Valle Viejo, Catamarca

*Santa Rosa, La Pampa

* Sa ...

-based financial institution

; Plant species named after Luther Burbank

* '' Canna'' 'Burbank'

* '' Chrysanthemum burbankii'' Makino

History

Makino was established in 1937 by Tsunezo Makino in Japan, developing Japan's first numerical control, numerically controlled (NC) milling machine in 1958 and Japan's first milling machine, machining centre in 1966.

The North America ...

(Asteraceae

The family Asteraceae, alternatively Compositae, consists of over 32,000 known species of flowering plants in over 1,900 genera within the order Asterales. Commonly referred to as the aster, daisy, composite, or sunflower family, Compositae w ...

)

* ''Myrica'' × ''burbankii'' A.Chev. (Myricaceae

The Myricaceae are a small family of dicotyledonous shrubs and small trees in the order Fagales. There are three genera in the family, although some botanists separate many species from ''Myrica'' into a fourth genus ''Morella''. About 55 specie ...

)

* ''Solanum'' × ''burbankii'' (''Solanum retroflexum

''Solanum retroflexum'', commonly known as umsobo (isiZulu), wonderberry or sunberry, is a historic heirloom fruiting shrub. Both common names are also used for the European black nightshade ('' Solanum nigrum'') in some places, particularly wher ...

'') (Solanaceae

The Solanaceae , or nightshades, are a family of flowering plants that ranges from annual and perennial herbs to vines, lianas, epiphytes, shrubs, and trees, and includes a number of agricultural crops, medicinal plants, spices, weeds, and orn ...

)

See also

* '' Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries, Their Practical Application'' *Luther Burbank Rose Parade and Festival

The Luther Burbank Rose Parade and Festival is an annual festival held in Santa Rosa, California celebrating Luther Burbank and his contribution to the world through a series of events. This festival has undergone changes throughout the years bu ...

References

Further reading

* *Burbank, Luther"The Training of the Human Plant"

Century Magazine, May 1907. * *Burbank, Luther. ''The Canna and the Calla: and some interesting work with striking results''. Paperback *Burbank, Luther with Wilbur Hall, ''Harvest of the Years''. This is Luther Burbank's autobiography published after his death in 1926. *Burbank, Luther. 1939.''An Architect of Nature''. Same details as ref. above, publisher: Watts & Co. (London) 'The Thinker's Library, No.76' *Burt, Olive W. ''Luther Burbank, Boy Wizard''. Biography published by Bobbs-Merrill in 1948 aimed at intermediate level students. *Anderson, N. O., & Olsen, R. T. (2015)

''A vast array of beauty: The accomplishments of the father of American ornamental plant breeding, Luther Burbank.''

HortScience, 50(2), 161-188. *Dreyer, Peter, ''A Gardener Touched With Genius The Life of Luther Burbank'', # L. Burbank Home & Gardens; New & expanded edition (January 1993), *Kraft, K. ''Luther Burbank, the Wizard and the Man''. New York : Meredith Press, 1967 ASIN: B0006BQE6C *Pandora, Katherine. "Luther Burbank". American National Biography. Retrieved on 2006-11-16. *Yogananda, Paramahansa. ''Autobiography of a Yogi''. Los Angeles : Self-Realization Fellowship, 1946 * *Tuomey, Honoria

Burbank, Scientist''."

Out West magazine, September 1905. pages 201-222. illustrated.

External links

A complete bibliography of books by and about Luther Burbank on WorldCat.

*

Frida Kahlo

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by the country's popular culture, ...

and Luther Burbank'']

* Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries and Their Practical Application

', 1914-1915, a 12-volume monographic series, is available online through the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center.

Luther Burbank Online

2013 — Selections from "Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries and Their Practical Application," 1914-1915, by an amateur gardener, 2013. *http://www.wschsgrf.org Official website of the Western Sonoma County Historical Society and Luther Burbank's Gold Ridge Experiment Farm *''Burbank Steps Forward with a Super-Wheat'',

Popular Science

''Popular Science'' (also known as ''PopSci'') is an American digital magazine carrying popular science content, which refers to articles for the general reader on science and technology subjects. ''Popular Science'' has won over 58 awards, incl ...

monthly, January 1919, page 22scanned by Google Books

* * *

Luther Burbank materials in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

* *Preece, John E. and Gale McGranahan

Luther Burbank’s Contributions to Walnuts

" ''HortScience'', Vol. 50:2, Feb. 2015, pp. 201–204. — Video slide presentation narrated by John E. Preece:

Luther Burbank's Contributions to Walnuts

" posted by cevizbiz cevizbiz, YouTube, November 14, 2015. {{DEFAULTSORT:Burbank, Luther 1849 births 1926 deaths American botanists American horticulturists American Unitarians Devotees of Paramahansa Yogananda History of Sonoma County, California People from Santa Rosa, California People from Lancaster, Massachusetts People from Sebastopol, California Hall of Fame for Great Americans inductees American eugenicists