Luis Walter Álvarez on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Luis Walter Alvarez (June 13, 1911 – September 1, 1988) was an American experimental physicist,

Physics: Decade by Decade

'. Facts On File, Incorporated; 2007. . p. 168. Alvarez also constructed an apparatus of

Alvarez's sister, Gladys, worked for

Alvarez's sister, Gladys, worked for

The radar system for which Alvarez is best known and which has played a major role in aviation, most particularly in the post-war Berlin airlift, was

The radar system for which Alvarez is best known and which has played a major role in aviation, most particularly in the post-war Berlin airlift, was

As a result of his radar work and the few months spent with Fermi, Alvarez arrived at Los Alamos in the spring of 1944, later than many of his contemporaries. The work on the " Little Boy" (a uranium bomb) was far along so Alvarez became involved in the design of the " Fat Man" (a plutonium bomb). The technique used for uranium, that of forcing the two sub- critical masses together using a type of gun, would not work with plutonium because the high level of background spontaneous neutrons would cause fissions as soon as the two parts approached each other, so heat and expansion would force the system apart before much energy has been released. It was decided to use a nearly critical sphere of plutonium and compress it quickly by explosives into a much smaller and denser core, a technical challenge at the time.

To create the symmetrical implosion required to compress the plutonium core to the required density, thirty-two explosive charges were to be simultaneously detonated around the spherical core. Using conventional explosive techniques with blasting caps, progress towards achieving simultaneity to within a small fraction of a microsecond was discouraging. Alvarez directed his graduate student,

As a result of his radar work and the few months spent with Fermi, Alvarez arrived at Los Alamos in the spring of 1944, later than many of his contemporaries. The work on the " Little Boy" (a uranium bomb) was far along so Alvarez became involved in the design of the " Fat Man" (a plutonium bomb). The technique used for uranium, that of forcing the two sub- critical masses together using a type of gun, would not work with plutonium because the high level of background spontaneous neutrons would cause fissions as soon as the two parts approached each other, so heat and expansion would force the system apart before much energy has been released. It was decided to use a nearly critical sphere of plutonium and compress it quickly by explosives into a much smaller and denser core, a technical challenge at the time.

To create the symmetrical implosion required to compress the plutonium core to the required density, thirty-two explosive charges were to be simultaneously detonated around the spherical core. Using conventional explosive techniques with blasting caps, progress towards achieving simultaneity to within a small fraction of a microsecond was discouraging. Alvarez directed his graduate student,  Again working with Johnston, Alvarez's last task for the Manhattan Project was to develop a set of calibrated microphone/ transmitters to be parachuted from an aircraft to measure the strength of the blast wave from the atomic explosion, so as to allow the scientists to calculate the bomb's energy. After being commissioned as a

Again working with Johnston, Alvarez's last task for the Manhattan Project was to develop a set of calibrated microphone/ transmitters to be parachuted from an aircraft to measure the strength of the blast wave from the atomic explosion, so as to allow the scientists to calculate the bomb's energy. After being commissioned as a

Returning to the University of California, Berkeley as a full professor, Alvarez had many ideas about how to use his wartime radar knowledge to improve particle accelerators. Though some of these were to bear fruit, the "big idea" of this time would come from Edwin McMillan with his concept of phase stability which led to the

Returning to the University of California, Berkeley as a full professor, Alvarez had many ideas about how to use his wartime radar knowledge to improve particle accelerators. Though some of these were to bear fruit, the "big idea" of this time would come from Edwin McMillan with his concept of phase stability which led to the

In 1964 Alvarez proposed what became known as the High Altitude Particle Physics Experiment (HAPPE), originally conceived as a large

In 1964 Alvarez proposed what became known as the High Altitude Particle Physics Experiment (HAPPE), originally conceived as a large

In 1980 Alvarez and his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, along with nuclear chemists Frank Asaro and

In 1980 Alvarez and his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, along with nuclear chemists Frank Asaro and

"Two-element variable-power spherical lens"

Patent US3305294A (December 1964)

About Luis Alvarez

] * * ttp://alsos.wlu.edu/qsearch.aspx?browse=people/Alvarez,+Luis Annotated bibliography for Luis Alvarez from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues* Garwin, Richard L., 1992,

Memorial Tribute For Luis W. Alvarez

in ''Memorial Tributes, National Academy of Engineering, Vol. 5''. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information, United States Department of Energy

Oral History interview transcript with Luiz Alvarez on 14 1967, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

Oral History interview transcript with Luiz Alvarez on 15 February 1967, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

{{DEFAULTSORT:Alvarez, Luis 1911 births 1988 deaths 20th-century American inventors 20th-century American physicists Accelerator physicists American agnostics American Nobel laureates American nuclear physicists American people of Asturian descent American people of Spanish descent American politicians of Cuban descent American scientific instrument makers California Republicans Collier Trophy recipients Enrico Fermi Award recipients Experimental physicists Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the American Physical Society Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Hispanic and Latino American scientists History of air traffic control Los Alamos National Laboratory personnel Manhattan Project people Members of JASON (advisory group) National Medal of Science laureates Nobel laureates in Physics Particle physicists People associated with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki People from San Francisco University of California, Berkeley faculty University of Chicago alumni Hispanic and Latino American physicists Deaths from esophageal cancer Deaths from cancer in California Presidents of the American Physical Society

inventor

An invention is a unique or novel device, method, composition, idea or process. An invention may be an improvement upon a machine, product, or process for increasing efficiency or lowering cost. It may also be an entirely new concept. If an ...

, and professor who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1968 for his discovery of resonance states in particle physics using the hydrogen bubble chamber. In 2007 the '' American Journal of Physics'' commented, "Luis Alvarez was one of the most brilliant and productive experimental physicists of the twentieth century."

After receiving his PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. albu ...

from the University of Chicago in 1936, Alvarez went to work for Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation f ...

at the Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 31 ...

at the University of California, Berkeley. Alvarez devised a set of experiments to observe K- electron capture in radioactive nuclei, predicted by the beta decay theory but never before observed. He produced tritium using the cyclotron and measured its lifetime. In collaboration with Felix Bloch, he measured the magnetic moment of the neutron.

In 1940, Alvarez joined the MIT Radiation Laboratory, where he contributed to a number of World War II radar projects, from early improvements to Identification friend or foe

Identification, friend or foe (IFF) is an identification system designed for command and control. It uses a transponder that listens for an ''interrogation'' signal and then sends a ''response'' that identifies the broadcaster. IFF systems usual ...

(IFF) radar beacons, now called transponders, to a system known as VIXEN for preventing enemy submarines from realizing that they had been found by the new airborne microwave radars. Enemy submarines would wait until the radar signal was getting strong and then submerge, escaping attack. But VIXEN transmitted a radar signal whose strength was the cube of the distance to the submarine so that as they approached the sub, the signal—as measured by the sub—got progressively weaker, and the sub assumed the plane was getting farther away and didn't submerge. The radar system for which Alvarez is best known and which has played a major role in aviation, most particularly in the post war Berlin airlift, was Ground Controlled Approach

In aviation a ground-controlled approach (GCA), is a type of service provided by air-traffic controllers whereby they guide aircraft to a safe landing, including in adverse weather conditions, based on primary radar images. Most commonly a GCA uses ...

(GCA). Alvarez spent a few months at the University of Chicago working on nuclear reactors for Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

before coming to Los Alamos to work for Robert Oppenheimer on the Manhattan project. Alvarez worked on the design of explosive lenses, and the development of exploding-bridgewire detonators. As a member of Project Alberta, he observed the Trinity nuclear test from a B-29 Superfortress, and later the bombing of Hiroshima

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the on ...

from the B-29 ''The Great Artiste

''The Great Artiste'' was a U.S. Army Air Forces Silverplate B-29 bomber (B-29-40-MO 44-27353, Victor number 89), assigned to the 393d Bomb Squadron, 509th Composite Group. The aircraft was named for its bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, i ...

''.

After the war Alvarez was involved in the design of a liquid hydrogen bubble chamber that allowed his team to take millions of photographs of particle interactions, develop complex computer systems to measure and analyze these interactions, and discover entire families of new particles and resonance states. This work resulted in his being awarded the Nobel Prize in 1968. He was involved in a project to x-ray the Egyptian pyramids

The Egyptian pyramids are ancient masonry structures located in Egypt. Sources cite at least 118 identified "Egyptian" pyramids. Approximately 80 pyramids were built within the Kingdom of Kush, now located in the modern country of Sudan. Of ...

to search for unknown chambers. With his son, geologist Walter Alvarez, he developed the Alvarez hypothesis which proposes that the extinction event

An extinction event (also known as a mass extinction or biotic crisis) is a widespread and rapid decrease in the biodiversity on Earth. Such an event is identified by a sharp change in the diversity and abundance of multicellular organisms. I ...

that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs was the result of an asteroid impact.

Alvarez was a member of the JASON Defense Advisory Group

JASON is an independent group of elite scientists which advises the United States government on matters of science and technology, mostly of a sensitive nature. The group was created in the aftermath of the Sputnik launch as a way to reinvigorate ...

, the Bohemian Club

The Bohemian Club is a private club with two locations: a city clubhouse in the Nob Hill district of San Francisco, California and the Bohemian Grove, a retreat north of the city in Sonoma County. Founded in 1872 from a regular meeting of journal ...

, and the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

.

Early life

Luis Walter Alvarez was born in San Francisco on June 13, 1911, the second child and oldest son ofWalter C. Alvarez

Walter Clement Alvarez (July 22, 1884June 18, 1978) was an American medical doctor of Spanish descent. He authored several dozen books on medicine, and wrote introductions and forewords for many others.

Biography

He was born in San Francisco and ...

, a physician, and his wife Harriet née Smyth, and a grandson of Luis F. Álvarez

Luis Fernández Álvarez (1 April 1853 – 24 May 1937) was a Spanish American physician and researcher who practiced in California and Hawaii.

Fernández was actually his principal surname (his father's surname), per Spanish naming custo ...

, a Spanish physician, born in Asturias, Spain, who lived in Cuba for a while and finally settled in the United States, who found a better method for diagnosing macular leprosy. He had an older sister, Gladys, a younger brother, Bob, and a younger sister, Bernice. His aunt, Mabel Alvarez

Mabel Alvarez (November 28, 1891 – March 13, 1985) was an American painter. Her works, often introspective and spiritual in nature, and her style is considered a contributing factor to the Southern California Modernism and California Impressi ...

, was a California artist specializing in oil painting.

He attended Madison School in San Francisco from 1918 to 1924, and then San Francisco Polytechnic High School. In 1926, his father became a researcher at the Mayo Clinic

The Mayo Clinic () is a nonprofit American academic medical center focused on integrated health care, education, and research. It employs over 4,500 physicians and scientists, along with another 58,400 administrative and allied health staff, ...

, and the family moved to Rochester, Minnesota

Rochester is a city in the U.S. state of Minnesota and the county seat of Olmsted County. Located on rolling bluffs on the Zumbro River's south fork in Southeast Minnesota, the city is the home and birthplace of the renowned Mayo Clinic.

Acco ...

, where Alvarez attended Rochester High School. He had always expected to attend the University of California, Berkeley, but at the urging of his teachers at Rochester, he instead went to the University of Chicago, where he received his bachelor's degree in 1932, his master's degree in 1934, and his PhD PHD or PhD may refer to:

* Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), an academic qualification

Entertainment

* '' PhD: Phantasy Degree'', a Korean comic series

* ''Piled Higher and Deeper'', a web comic

* Ph.D. (band), a 1980s British group

** Ph.D. (Ph.D. albu ...

in 1936. As an undergraduate, he belonged to the Phi Gamma Delta

Phi Gamma Delta (), commonly known as Fiji, is a social fraternity with more than 144 active chapters and 10 colonies across the United States and Canada. It was founded at Jefferson College, Pennsylvania, in 1848. Along with Phi Kappa Psi, Phi ...

fraternity

A fraternity (from Latin language, Latin ''wiktionary:frater, frater'': "brother (Christian), brother"; whence, "wiktionary:brotherhood, brotherhood") or fraternal organization is an organization, society, club (organization), club or fraternal ...

. As a postgraduate he moved to Gamma Alpha.

In 1932, as a graduate student at Chicago, he discovered physics there and had the rare opportunity to use the equipment of legendary physicist Albert A. Michelson.Alfred B. Bortz. Physics: Decade by Decade

'. Facts On File, Incorporated; 2007. . p. 168. Alvarez also constructed an apparatus of

Geiger counter

A Geiger counter (also known as a Geiger–Müller counter) is an electronic instrument used for detecting and measuring ionizing radiation. It is widely used in applications such as radiation dosimetry, radiological protection, experimental ph ...

tubes arranged as a cosmic ray telescope

A cosmic-ray observatory is a scientific installation built to detect high-energy-particles coming from space called cosmic rays. This typically includes photons (high-energy light), electrons, protons, and some heavier nuclei, as well as antimat ...

, and under the aegis of his faculty advisor Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

, conducted an experiment in Mexico City to measure the so-called East–West effect of cosmic rays. Observing more incoming radiation from the west, Alvarez concluded that primary cosmic rays were positively charged. Compton submitted the resulting paper to the ''Physical Review

''Physical Review'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal established in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research as well as scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the American Physical S ...

'', with Alvarez's name at the top.

Alvarez was an agnostic even though his father had been a deacon in a Congregational church.

Early work

Alvarez's sister, Gladys, worked for

Alvarez's sister, Gladys, worked for Ernest Lawrence

Ernest Orlando Lawrence (August 8, 1901 – August 27, 1958) was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation f ...

as a part-time secretary, and mentioned Alvarez to Lawrence. Lawrence then invited Alvarez to tour the Century of Progress exhibition in Chicago with him. After he completed his oral exam

The oral exam (also oral test or '; ' in German-speaking nations) is a practice in many schools and disciplines in which an examiner poses questions to the student in spoken form. The student has to answer the question in such a way as to demons ...

s in 1936, Alvarez, now engaged to be married to Geraldine Smithwick, asked his sister to see if Lawrence had any jobs available at the Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 31 ...

. A telegram soon arrived from Gladys with a job offer from Lawrence. This started a long association with the University of California, Berkeley. Alvarez and Smithwick were married in one of the chapels at the University of Chicago and then headed for California. They had two children, Walter

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 19 ...

and Jean. They were divorced in 1957. On December 28, 1958, he married Janet L. Landis, and had two more children, Donald and Helen.

At the Radiation Laboratory he worked with Lawrence's experimental team, which was supported by a group of theoretical physicists headed by Robert Oppenheimer. Alvarez devised a set of experiments to observe K- electron capture in radioactive nuclei, predicted by the beta decay theory but never observed. Using magnets to sweep aside the positron

The positron or antielectron is the antiparticle or the antimatter counterpart of the electron. It has an electric charge of +1 '' e'', a spin of 1/2 (the same as the electron), and the same mass as an electron. When a positron collides ...

s and electrons emanating from his radioactive sources, he designed a special purpose Geiger counter to detect only the "soft" X-rays coming from K capture. He published his results in the ''Physical Review

''Physical Review'' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal established in 1893 by Edward Nichols. It publishes original research as well as scientific and literature reviews on all aspects of physics. It is published by the American Physical S ...

'' in 1937.

When deuterium (hydrogen-2) is bombarded with deuterium, the fusion reaction yields either tritium (hydrogen-3) plus a proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

or helium-3

Helium-3 (3He see also helion) is a light, stable isotope of helium with two protons and one neutron (the most common isotope, helium-4, having two protons and two neutrons in contrast). Other than protium (ordinary hydrogen), helium-3 is the ...

plus a neutron (). This is one of the most basic fusion reactions, and the foundation of the thermonuclear weapon and the current research on controlled nuclear fusion. At that time the stability of these two reaction products was unknown, but based on existing theories Hans Bethe thought that tritium would be stable and helium-3 unstable. Alvarez proved the reverse by using his knowledge of the details of the 60-inch cyclotron operation. He tuned the machine to accelerate doubly ionized helium-3 nuclei and was able to get a beam of accelerated ions, thus using the cyclotron as a kind of super mass spectrometer. As the accelerated helium came from deep gas wells where it had been for millions of years, the helium-3 component had to be stable. Afterwards Alvarez produced the radioactive tritium using the cyclotron and the reaction and measured its lifetime.

In 1938, again using his knowledge of the cyclotron and inventing what are now known as time-of-flight techniques, Alvarez created a mono-energetic beam of thermal neutrons. With this he began a long series of experiments, collaborating with Felix Bloch, to measure the magnetic moment of the neutron. Their result of , published in 1940, was a major advance over earlier work.

World War II

Radiation Laboratory

The British Tizard Mission to the United States in 1940 demonstrated to leading American scientists the successful application of the cavity magnetron to produce short wavelength pulsed radar. The National Defense Research Committee, established only months earlier by PresidentFranklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, created a central national laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) for the purpose of developing military applications of microwave radar. Lawrence immediately recruited his best "cyclotroneers", among them Alvarez, who joined this new laboratory, known as the Radiation Laboratory

The Radiation Laboratory, commonly called the Rad Lab, was a microwave and radar research laboratory located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was first created in October 1940 and operated until 31 ...

, on November 11, 1940. Alvarez contributed to a number of radar projects, from early improvements to Identification Friend or Foe

Identification, friend or foe (IFF) is an identification system designed for command and control. It uses a transponder that listens for an ''interrogation'' signal and then sends a ''response'' that identifies the broadcaster. IFF systems usual ...

(IFF) radar beacons, now called transponders, to a system known as VIXEN for preventing enemy submarines from realizing that they had been found by the new airborne microwave radars.

One of the first projects was to build equipment to transition from the British long-wave radar to the new microwave centimeter-band radar made possible by the cavity magnetron. In working on the Microwave Early Warning

Microwave is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelengths ranging from about one meter to one millimeter corresponding to frequencies between 300 MHz and 300 GHz respectively. Different sources define different frequency rang ...

system (MEW), Alvarez invented a linear dipole array antenna that not only suppressed the unwanted side lobes of the radiation field but also could be electronically scanned without the need for mechanical scanning. This was the first microwave phased-array antenna, and Alvarez used it not only in MEW but in two additional radar systems. The antenna enabled the Eagle precision bombing radar to support precision bombing in bad weather or through clouds. It was completed rather late in the war; although a number of B-29

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fly ...

s were equipped with Eagle and it worked well, it came too late to make much difference.

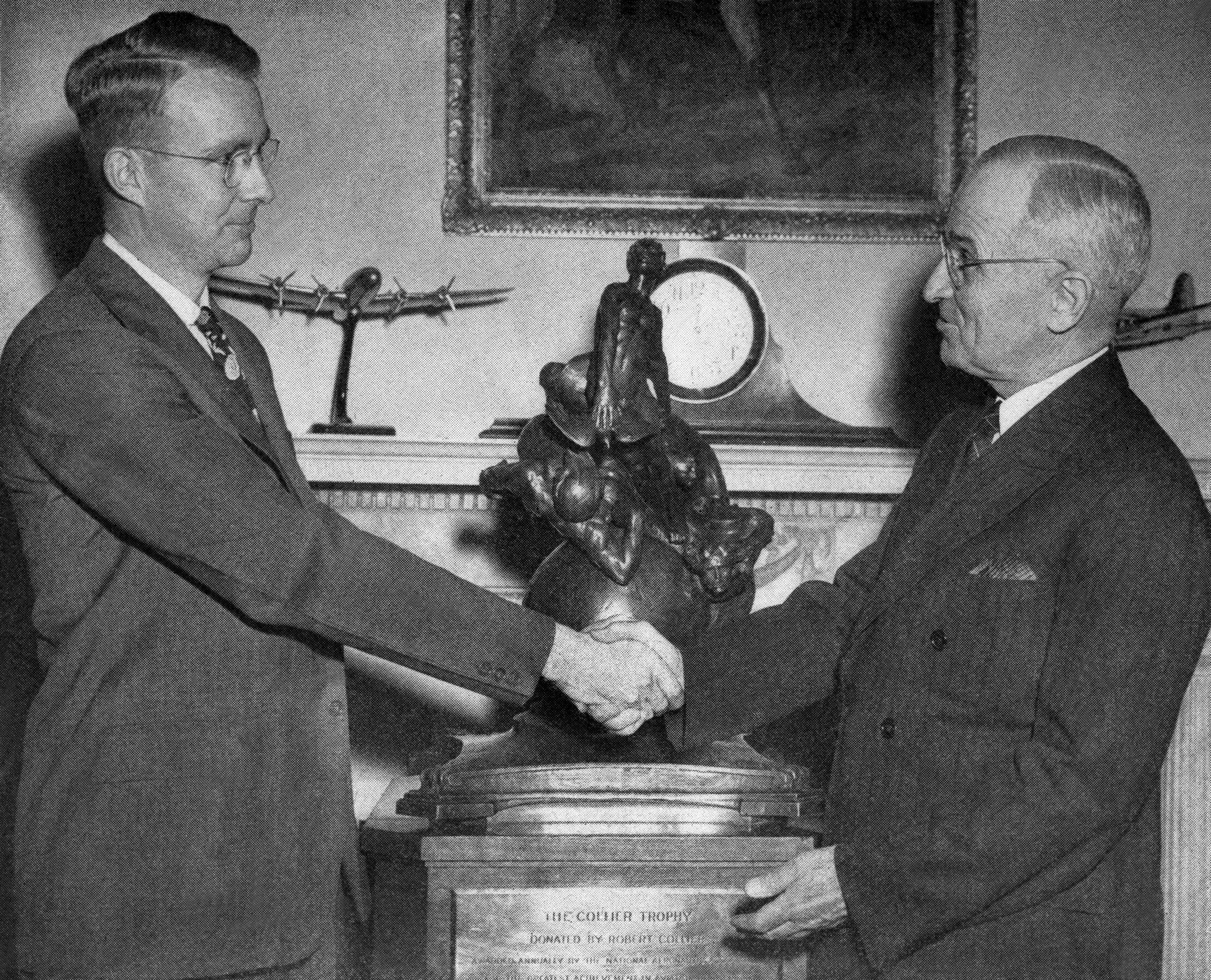

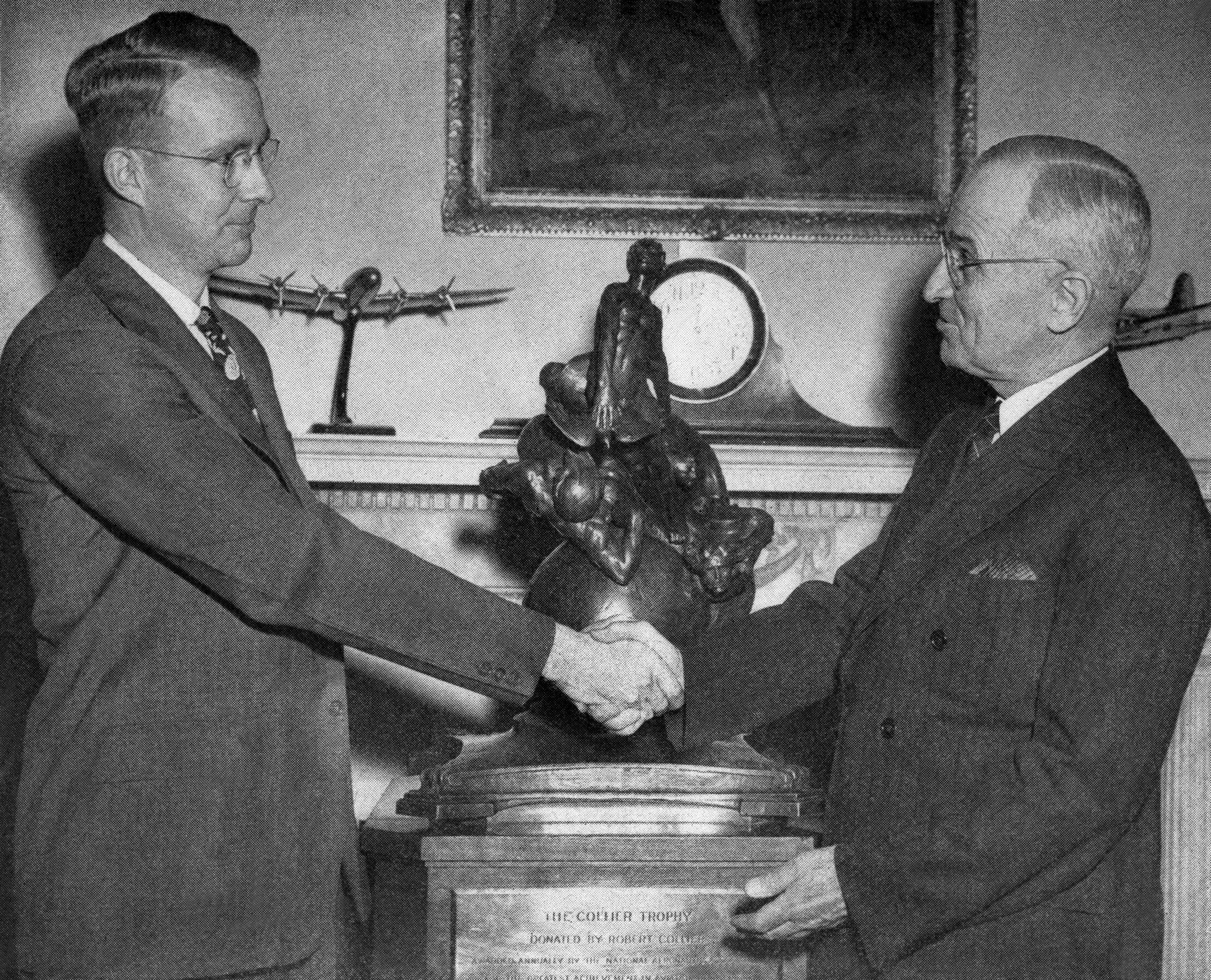

The radar system for which Alvarez is best known and which has played a major role in aviation, most particularly in the post-war Berlin airlift, was

The radar system for which Alvarez is best known and which has played a major role in aviation, most particularly in the post-war Berlin airlift, was Ground Controlled Approach

In aviation a ground-controlled approach (GCA), is a type of service provided by air-traffic controllers whereby they guide aircraft to a safe landing, including in adverse weather conditions, based on primary radar images. Most commonly a GCA uses ...

(GCA). Using Alvarez's dipole antenna to achieve a very high angular resolution

Angular resolution describes the ability of any image-forming device such as an optical or radio telescope, a microscope, a camera, or an eye, to distinguish small details of an object, thereby making it a major determinant of image resolution. ...

, GCA allows ground-based radar operators to watch special precision displays to guide a landing airplane to the runway by transmitting verbal commands to the pilot. The system was simple, direct, and worked well, even with previously untrained pilots. It was so successful that the military continued to use it for many years after the war, and it was still in use in some countries in the 1980s. Alvarez was awarded the National Aeronautic Association's Collier Trophy

The Robert J. Collier Trophy is an annual aviation award administered by the U.S. National Aeronautic Association (NAA), presented to those who have made "the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics in America, with respect to im ...

in 1945 "for his conspicuous and outstanding initiative in the concept and development of the Ground Control Approach system for safe landing of aircraft under all weather and traffic conditions".

Alvarez spent the summer of 1943 in England testing GCA, landing planes returning from battle in bad weather, and also training the British in the use of the system. While there he encountered the young Arthur C. Clarke

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke (16 December 191719 March 2008) was an English science-fiction writer, science writer, futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host.

He co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 film '' 2001: A Spac ...

, who was an RAF radar technician. Clarke subsequently used his experiences at the radar research station as the basis for his novel ''Glide Path

Instrument landing system glide path, commonly referred to as a glide path (G/P) or glide slope (G/S), is "a system of vertical guidance embodied in the instrument landing system which indicates the vertical deviation of the aircraft from its o ...

'', which contains a thinly disguised version of Alvarez. Clarke and Alvarez developed a long-term friendship.

Manhattan Project

In the fall of 1943, Alvarez returned to the United States with an offer from Robert Oppenheimer to work at Los Alamos on the Manhattan Project. However, Oppenheimer suggested that he first spend a few months at the University of Chicago working withEnrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian (later naturalized American) physicist and the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1. He has been called the "architect of the nuclear age" and ...

before coming to Los Alamos. During these months, General Leslie Groves asked Alvarez to think of a way that the US could find out if the Germans were operating any nuclear reactors, and, if so, where they were. Alvarez suggested that an airplane could carry a system to detect the radioactive gases that a reactor produces, particularly xenon-133. The equipment did fly over Germany, but detected no radioactive xenon because the Germans had not built a reactor capable of a chain reaction. This was the first idea of monitoring fission product

Nuclear fission products are the atomic fragments left after a large atomic nucleus undergoes nuclear fission. Typically, a large nucleus like that of uranium fissions by splitting into two smaller nuclei, along with a few neutrons, the release ...

s for intelligence gathering. It would become extremely important after the war.

Lawrence H. Johnston

Lawrence Harding Johnston (February 11, 1918 – December 4, 2011) was an American physicist, a young contributor to the Manhattan Project. He was the only man to witness all three atomic explosions in 1945: the Trinity nuclear test in New Me ...

, to use a large capacitor to deliver a high voltage charge directly to each explosive lens, replacing blasting caps with exploding-bridgewire detonators. The exploding wire detonated the thirty-two charges to within a few tenths of a microsecond. The invention was critical to the success of the implosion-type nuclear weapon. He also supervised the RaLa Experiment

The RaLa Experiment, or RaLa, was a series of tests during and after the Manhattan Project designed to study the behavior of converging shock waves to achieve the spherical implosion necessary for compression of the plutonium pit of the nuclear we ...

s. Alvarez later wrote that:

Again working with Johnston, Alvarez's last task for the Manhattan Project was to develop a set of calibrated microphone/ transmitters to be parachuted from an aircraft to measure the strength of the blast wave from the atomic explosion, so as to allow the scientists to calculate the bomb's energy. After being commissioned as a

Again working with Johnston, Alvarez's last task for the Manhattan Project was to develop a set of calibrated microphone/ transmitters to be parachuted from an aircraft to measure the strength of the blast wave from the atomic explosion, so as to allow the scientists to calculate the bomb's energy. After being commissioned as a lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

in the United States Army, he observed the Trinity nuclear test from a B-29 Superfortress that also carried fellow Project Alberta members Harold Agnew

Harold Melvin Agnew (March 28, 1921 – September 29, 2013) was an American physicist, best known for having flown as a scientific observer on the Hiroshima bombing mission and, later, as the third director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory ...

and Deak Parsons (who were respectively commissioned at the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

).

Flying in the B-29 Superfortress ''The Great Artiste

''The Great Artiste'' was a U.S. Army Air Forces Silverplate B-29 bomber (B-29-40-MO 44-27353, Victor number 89), assigned to the 393d Bomb Squadron, 509th Composite Group. The aircraft was named for its bombardier, Captain Kermit Beahan, i ...

'' in formation with the ''Enola Gay

The ''Enola Gay'' () is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Colonel Paul Tibbets. On 6 August 1945, piloted by Tibbets and Robert A. Lewis during the final stages of World War II, it be ...

'', Alvarez and Johnston measured the blast effect of the Little Boy bomb which was dropped on Hiroshima. A few days later, again flying in ''The Great Artiste'', Johnston used the same equipment to measure the strength of the Nagasaki explosion.

Bubble chamber

Returning to the University of California, Berkeley as a full professor, Alvarez had many ideas about how to use his wartime radar knowledge to improve particle accelerators. Though some of these were to bear fruit, the "big idea" of this time would come from Edwin McMillan with his concept of phase stability which led to the

Returning to the University of California, Berkeley as a full professor, Alvarez had many ideas about how to use his wartime radar knowledge to improve particle accelerators. Though some of these were to bear fruit, the "big idea" of this time would come from Edwin McMillan with his concept of phase stability which led to the synchrocyclotron

A synchrocyclotron is a special type of cyclotron, patented by Edwin McMillan in 1952, in which the frequency of the driving RF electric field is varied to compensate for relativistic effects as the particles' velocity begins to approach the spe ...

. Refining and extending this concept, the Lawrence team would build the world's then-largest proton accelerator, the Bevatron, which began operating in 1954. Though the Bevatron could produce copious amounts of interesting particles, particularly in secondary collisions, these complex interactions were hard to detect and analyze at the time.

Seizing upon a new development to visualize particle tracks, created by Donald Glaser

Donald Arthur Glaser (September 21, 1926 – February 28, 2013) was an Americans, American physicist, neurobiologist, and the winner of the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physics for his invention of the bubble chamber used in subatomic particle physic ...

and known as a bubble chamber, Alvarez realized the device was just what was needed, if only it could be made to function with liquid hydrogen. Hydrogen nuclei, which are proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

s, made the simplest and most desirable target for interactions with the particles produced by the Bevatron. He began a development program to build a series of small chambers, and championed the device to Ernest Lawrence.

The Glaser device was a small glass cylinder () filled with ether. By suddenly reducing the pressure in the device, the liquid could be placed into a temporary superheated state, which would boil along the disturbed track of a particle passing through. Glaser was able to maintain the superheated state for a few seconds before spontaneous boiling took place. The Alvarez team built chambers of 1.5 in, 2.5 in, 4 in, 10 in, and 15 in using liquid hydrogen, and constructed of metal with glass windows, so that the tracks could be photographed. The chamber could be cycled in synchronization with the accelerator beam, a picture could be taken, and the chamber recompressed in time for the next beam cycle.

This program built a liquid hydrogen bubble chamber almost 7 feet (2 meters) long, employed dozens of physicists and graduate students together with hundreds of engineers and technicians, took millions of photographs of particle interactions, developed computer systems to measure and analyze the interactions, and discovered families of new particles and resonance states. This work resulted in the Nobel Prize in Physics for Alvarez in 1968, "For his decisive contributions to elementary particle physics, in particular the discovery of a large number of resonant states, made possible through his development of the technique of using hydrogen bubble chambers and data analysis."

Scientific detective

superconducting magnet

A superconducting magnet is an electromagnet made from coils of superconducting wire. They must be cooled to cryogenic temperatures during operation. In its superconducting state the wire has no electrical resistance and therefore can conduct mu ...

carried to high altitude by a balloon in order to study extremely high-energy particle interactions. In time the focus of the experiment changed toward the study of cosmology and the role of both particles and radiation in the early universe

The chronology of the universe describes the history and future of the universe according to Big Bang cosmology.

Research published in 2015 estimates the earliest stages of the universe's existence as taking place 13.8 billion years ago, wit ...

. This work was a large effort, carrying detectors aloft with high-altitude balloon flights and high-flying U-2 aircraft, and an early precursor of the COBE satellite-born experiments on the cosmic background radiation (which resulted in the award of the 2006 Nobel Prize, shared by George Smoot and John Mather.)

Alvarez proposed Muon tomography in 1965 to search the Egyptian pyramids

The Egyptian pyramids are ancient masonry structures located in Egypt. Sources cite at least 118 identified "Egyptian" pyramids. Approximately 80 pyramids were built within the Kingdom of Kush, now located in the modern country of Sudan. Of ...

for unknown chambers. Using naturally occurring cosmic rays, his plan was to place spark chambers, standard equipment in the high-energy particle physics of this time, beneath the Pyramid of Khafre in a known chamber. By measuring the counting rate of the cosmic rays in different directions the detector would reveal the existence of any void in the overlaying rock structure.

Alvarez assembled a team of physicists and archeologists from the United States and Egypt, the recording equipment was constructed and the experiment carried out, though it was interrupted by the 1967 Six-Day War. Restarted after the war, the effort continued, recording and analyzing the penetrating cosmic rays until 1969 when he reported to the American Physical Society

The American Physical Society (APS) is a not-for-profit membership organization of professionals in physics and related disciplines, comprising nearly fifty divisions, sections, and other units. Its mission is the advancement and diffusion of k ...

that no chambers had been found in the 19% of the pyramid surveyed.

In November 1966 '' Life'' published a series of photographs from the film

A film also called a movie, motion picture, moving picture, picture, photoplay or (slang) flick is a work of visual art that simulates experiences and otherwise communicates ideas, stories, perceptions, feelings, beauty, or atmosphere ...

that Abraham Zapruder

Abraham Zapruder (May 15, 1905 – August 30, 1970) was a Ukrainian-born American clothing manufacturer who witnessed the assassination of United States President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963. He unexpectedly captured ...

took of the Kennedy assassination. Alvarez, an expert in optics and photoanalysis Photoanalysis (or photo analysis) refers to the study of pictures to compile various types of data, for example, to measure the size distribution of virtually anything that can be captured by photo. Photoanalysis technology has changed the way mine ...

, became intrigued by the pictures and began to study what could be learned from the film. Alvarez demonstrated both in theory and experiment that the backward snap of the President's head was consistent with his being shot from behind being called the "jet-effect" theory. Prominent conspiracy theorists attempted to refute his experiment – see Last Second in Dallas by Josiah Thompson, however, doctor Nicholas Nalli, Ph.D supports Alvarez's theory which is consistent with a shot from behind. He also investigated the timing of the gunshots and the shockwave which disturbed the camera, and the speed of the camera, pointing out a number of things which the FBI photo analysts either overlooked or got wrong. He produced a paper intended as a tutorial, with informal advice for the physicist intent on arriving at the truth.

Dinosaur extinction

Helen Michel

Helen Vaughn Michel (born 1932) is an American chemist best known for her efforts in fields including analytical chemistry and archaeological science, and specific processes such as neutron activation analysis and radiocarbon dating. Her work ...

, "uncovered a calamity that literally shook the Earth and is one of the great discoveries about Earth's history".

During the 1970s, Walter Alvarez was doing geologic research in central Italy. There he had located an outcrop on the walls of a gorge whose limestone layers included strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as ei ...

both above and below the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary

The Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary, formerly known as the Cretaceous–Tertiary (K–T) boundary, is a geological signature, usually a thin band of rock containing much more iridium than other bands. The K–Pg boundary marks the end of ...

. Exactly at the boundary is a thin layer of clay. Walter told his father that the layer marked where the dinosaurs and much else became extinct and that nobody knew why, or what the clay was about—it was a big mystery and he intended, to solve it.

Alvarez had access to the nuclear chemists

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

*Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

at the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory and was able to work with Frank Asaro and Helen Michel

Helen Vaughn Michel (born 1932) is an American chemist best known for her efforts in fields including analytical chemistry and archaeological science, and specific processes such as neutron activation analysis and radiocarbon dating. Her work ...

, who used the technique of neutron activation analysis

Neutron activation analysis (NAA) is the nuclear process used for determining the concentrations of elements in many materials. NAA allows discrete sampling of elements as it disregards the chemical form of a sample, and focuses solely on atomic ...

. In 1980, Alvarez, Alvarez, Asaro, and Michel published a seminal paper proposing an extraterrestrial cause for the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction (then called the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction). In the years following the publication of their article, the clay was also found to contain soot, glassy spherules, shocked quartz crystals, microscopic diamonds, and rare minerals formed only under conditions of great temperature and pressure.

Publication of the 1980 paper brought criticism from the geologic community, and an often acrimonious scientific debate ensued. Ten years later, and after Alvarez's death, evidence of a large impact crater called Chicxulub

The Chicxulub crater () is an impact crater buried underneath the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. Its center is offshore near the community of Chicxulub, after which it is named. It was formed slightly over 66 million years ago when a large a ...

was found off the coast of Mexico, providing support for the theory. Other researchers later found that the end-Cretaceous extinction of the dinosaurs may have occurred rapidly in geologic terms, over thousands of years, rather than millions of years as had previously been supposed. Others continue to study alternative extinction causes such as increased volcanism, particularly the massive Deccan Traps

The Deccan Traps is a large igneous province of west-central India (17–24°N, 73–74°E). It is one of the largest volcanic features on Earth, taking the form of a large shield volcano. It consists of numerous layers of solidified flood ...

eruptions that occurred around the same time, and climate change, checking against the fossil record. However, on March 4, 2010, a panel of 41 scientists agreed that the Chicxulub asteroid impact triggered the mass extinction.

Aviation

In his autobiography, Alvarez said, "I think of myself as having had two separate careers, one in science and one in aviation. I've found the two almost equally rewarding." An important contributor to this was his enjoyment of flying. He learned to fly in 1933, later earning instrument and multi-engine ratings. Over the next 50 years he accumulated over 1000 hours of flight time, most of it as pilot in command. He said, "I found few activities as satisfying as being pilot in command with responsibility for my passengers' lives." Alvarez made numerous professional contributions to aviation. During World War II he led the development of multiple aviation-related technologies. Several of his projects are described above, including Ground Controlled Approach (GCA) for which he was awarded the Collier Trophy in 1945. He also held the basic patent for the radar transponder, for which he assigned rights to the U.S. government for $1. Later in his career Alvarez served on multiple high level advisory committees related to civilian and military aviation. These included a Federal Aviation Administration task group on futureair navigation

The basic principles of air navigation are identical to general navigation, which includes the process of planning, recording, and controlling the movement of a craft from one place to another.

Successful air navigation involves piloting an air ...

and air traffic control systems, the President's Science Advisory Committee Military Aircraft Panel, and a committee studying how the scientific community could help improve the United States' capabilities for fighting a nonnuclear war.

Alvarez's aviation responsibilities led to many adventures. For example, while working on GCA he became the first civilian to fly a low approach with his view outside the cockpit obstructed. He also flew many military aircraft from the co-pilot's seat, including a B-29 Superfortress and a Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. In addition, he survived a crash during World War II as a passenger in a Miles Master.

Death

Alvarez died on September 1, 1988, of complications from a succession of recent operations foresophageal cancer

Esophageal cancer is cancer arising from the esophagus—the food pipe that runs between the throat and the stomach. Symptoms often include difficulty in swallowing and weight loss. Other symptoms may include pain when swallowing, a hoarse voice ...

. His remains were cremated, and his ashes were scattered over Monterey Bay. His papers are in The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library in the center of the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, is the university's primary special-collections library. It was acquired from its founder, Hubert Howe Bancroft, in 1905, with the proviso that it retai ...

at the University of California, Berkeley.

Awards and honors

* Fellow of theAmerican Physical Society

The American Physical Society (APS) is a not-for-profit membership organization of professionals in physics and related disciplines, comprising nearly fifty divisions, sections, and other units. Its mission is the advancement and diffusion of k ...

(1939) and President (1969)

* Collier Trophy

The Robert J. Collier Trophy is an annual aviation award administered by the U.S. National Aeronautic Association (NAA), presented to those who have made "the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics in America, with respect to im ...

of the National Aeronautics Association (1946)

* Member of the National Academy of Sciences

The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) is a United States nonprofit, non-governmental organization. NAS is part of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) and the Nati ...

(1947)

* Medal for Merit (1947)

* Fellow of the American Philosophical Society (1953)

* Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1958)

* California Scientist of the Year (1960)

* Albert Einstein Award

The Albert Einstein Award (sometimes mistakenly called the ''Albert Einstein Medal'' because it was accompanied with a gold medal) was an award in theoretical physics, given periodically from 1951 to 1979, that was established to recognize high ac ...

(1961)

* Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement (1961)

* National Medal of Science (1963)

* Michelson Award (1965)

* Nobel Prize in Physics (1968)

* Member of the National Academy of Engineering (1969)

* University of Chicago Alumni Medal (1978)

* National Inventors Hall of Fame (1978)

* Enrico Fermi award of the US Department of Energy (1987)

* IEEE Honorary Membership IEEE Honorary Membership is an honorary type of membership of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), that is given for life to an individual. It is awarded by the board of directors of IEEE to people 'who have rendered meri ...

(1988)

* The Boy Scouts of America named their Cub Scout SUPERNOVA award for Alvarez (2012)

* Minor planet 3581 Alvarez

3581 Alvarez, provisional designation ', is a carbonaceous asteroid and a very large Mars-crosser on an eccentric orbit from the asteroid belt, approximately in diameter. It was discovered on 23 April 1985, by American astronomer couple Carolyn a ...

is named after him and his son, Walter Alvarez.

Selected publications

"Two-element variable-power spherical lens"

Patent US3305294A (December 1964)

Patents

* Golf training device * Electronuclear Reactor * Optical range finder with variable angle exponential prism * Two-element variable-power spherical lens * Variable-power lens and system * Subatomic particle detector with liquid electron multiplication medium * Method of making Fresnelled optical element matrix * Optical element of reduced thickness * Method of forming an optical element of reduced thickness * Deuterium tagged articles such as explosives and method for detection thereof * Stabilized zoom binocular * Stand alone collision avoidance system * Television viewer * Stabilized zoom binocular * Optically stabilized camera lens system * Nitrogen detection * Inertial pendulum optical stabilizerAlvarez, Luis W., and Sporer, Stephen F. (March 27, 1990). "Inertial pendulum optical stabilizer". U.S. Patent No. 4,911,541. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.Citations

General references

* * * *External links

* including the Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1968, "Recent Developments in Particle Physics"About Luis Alvarez

] * * ttp://alsos.wlu.edu/qsearch.aspx?browse=people/Alvarez,+Luis Annotated bibliography for Luis Alvarez from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues* Garwin, Richard L., 1992,

Memorial Tribute For Luis W. Alvarez

in ''Memorial Tributes, National Academy of Engineering, Vol. 5''. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information, United States Department of Energy

Oral History interview transcript with Luiz Alvarez on 14 1967, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

Oral History interview transcript with Luiz Alvarez on 15 February 1967, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives

{{DEFAULTSORT:Alvarez, Luis 1911 births 1988 deaths 20th-century American inventors 20th-century American physicists Accelerator physicists American agnostics American Nobel laureates American nuclear physicists American people of Asturian descent American people of Spanish descent American politicians of Cuban descent American scientific instrument makers California Republicans Collier Trophy recipients Enrico Fermi Award recipients Experimental physicists Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Fellows of the American Physical Society Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences Hispanic and Latino American scientists History of air traffic control Los Alamos National Laboratory personnel Manhattan Project people Members of JASON (advisory group) National Medal of Science laureates Nobel laureates in Physics Particle physicists People associated with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki People from San Francisco University of California, Berkeley faculty University of Chicago alumni Hispanic and Latino American physicists Deaths from esophageal cancer Deaths from cancer in California Presidents of the American Physical Society