Louis Brandeis Supreme Court nomination on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

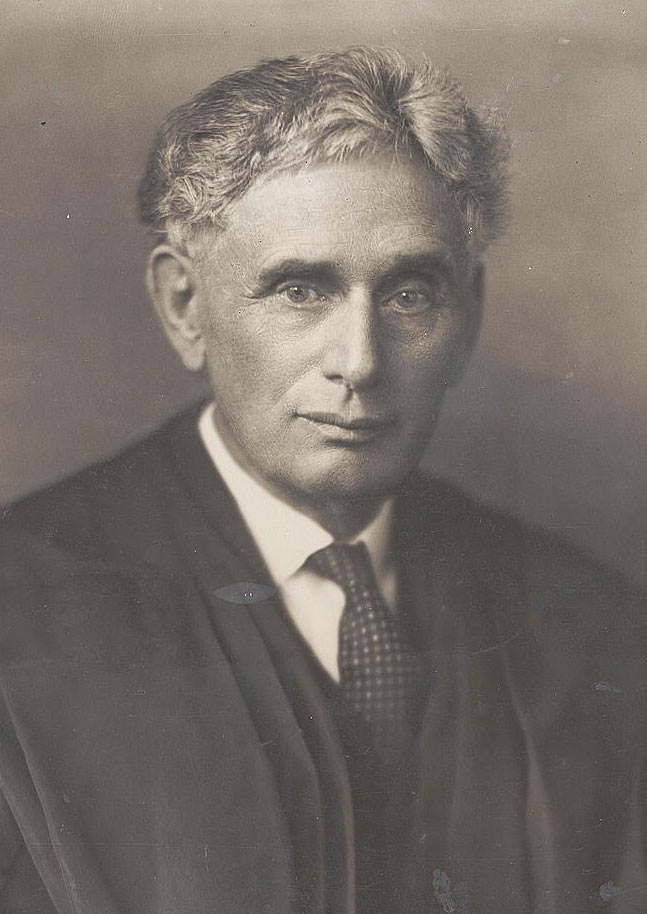

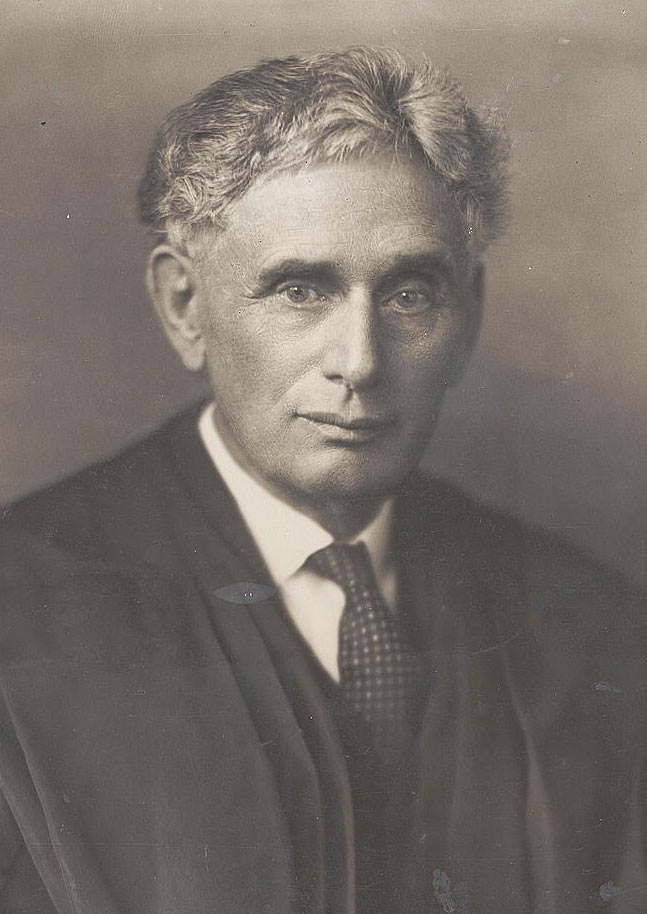

Louis Brandeis was

On January 28, 1916, President

On January 28, 1916, President

Brandeis' nomination ignited an intense confirmation battle. Brandeis' nomination evoked a polarized and vocal reaction. The widespread attention and intense fight over the nomination was in contrast to most preceding Supreme Court nomination processes, which had been low-key and quiet. It was considered among the most contentious nominations up to that point.

Many opponents took issue with the "radicalism" of Brandeis. The nomination quickly received strong conservative backlash. '' The Sun'' newspaper of

Brandeis' nomination ignited an intense confirmation battle. Brandeis' nomination evoked a polarized and vocal reaction. The widespread attention and intense fight over the nomination was in contrast to most preceding Supreme Court nomination processes, which had been low-key and quiet. It was considered among the most contentious nominations up to that point.

Many opponents took issue with the "radicalism" of Brandeis. The nomination quickly received strong conservative backlash. '' The Sun'' newspaper of

Throughout the confirmation fight, President Wilson stood by his nominee, and Brandeis' confirmation was regarded as a significant victory for Wilson. The president called Brandeis a, "friend of all just men and a lover of the right."

Throughout the confirmation fight, President Wilson stood by his nominee, and Brandeis' confirmation was regarded as a significant victory for Wilson. The president called Brandeis a, "friend of all just men and a lover of the right."

After the subcommittee ended hearings in March, the full committee began further hearings in May. At one point Brandeis considered testifying, but ultimately did not. During the time of these hearings, Brandeis personally met in

After the subcommittee ended hearings in March, the full committee began further hearings in May. At one point Brandeis considered testifying, but ultimately did not. During the time of these hearings, Brandeis personally met in

On May 24, 1916, in a 10–8 vote, the Judiciary Committee voted to report favorably on Brandeis' nomination. The vote was a party-line vote, with all Democrats voting in support of reporting favorably, and all Republicans voting against it. While Senator Albert B. Cummins was physically absent, his vote against the nomination was allowed to be counted.

The committee's majority report defended Brandeis against allegations that had been raised of alleged misconduct. It also made a point that Brandeis would not be the first Supreme Court judge appointed amid what it contended were tense and unjust attacks. It also claimed that letters and petitions in support of the nomination significantly outweighed the opposition raised to the nomination.

The committee's minority report alleged that twelve allegations of misconduct by Brandeis had been sustained by evidence and that it had been proven that Brandeis had a bad reputation among lawyers of the Boston bar. It argued that Brandeis had his integrity more seriously questioned than any prior justice appointed to the Supreme Court and that his nomination had lowered the standard for appointment to the court.

After the vote, ''The New York Times'' wrote,

In a memorable editorial, ''The New York Times'' continued to voice the opinion that Brandeis was suited not for the courts, but was rather suited for the legislature. It complained that Brandeis was,

''The New York Times'' also wrote,

On May 24, 1916, in a 10–8 vote, the Judiciary Committee voted to report favorably on Brandeis' nomination. The vote was a party-line vote, with all Democrats voting in support of reporting favorably, and all Republicans voting against it. While Senator Albert B. Cummins was physically absent, his vote against the nomination was allowed to be counted.

The committee's majority report defended Brandeis against allegations that had been raised of alleged misconduct. It also made a point that Brandeis would not be the first Supreme Court judge appointed amid what it contended were tense and unjust attacks. It also claimed that letters and petitions in support of the nomination significantly outweighed the opposition raised to the nomination.

The committee's minority report alleged that twelve allegations of misconduct by Brandeis had been sustained by evidence and that it had been proven that Brandeis had a bad reputation among lawyers of the Boston bar. It argued that Brandeis had his integrity more seriously questioned than any prior justice appointed to the Supreme Court and that his nomination had lowered the standard for appointment to the court.

After the vote, ''The New York Times'' wrote,

In a memorable editorial, ''The New York Times'' continued to voice the opinion that Brandeis was suited not for the courts, but was rather suited for the legislature. It complained that Brandeis was,

''The New York Times'' also wrote,

nominated

A candidate, or nominee, is the prospective recipient of an award or honor, or a person seeking or being considered for some kind of position; for example:

* to be elected to an office — in this case a candidate selection procedure occurs.

* ...

to serve as an associate justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some sta ...

of the Supreme Court of the United States by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

on January 28, 1916, after the death in office

A death in office is the death of a person who was incumbent of an office-position until the time of death. Such deaths have been usually due to natural causes, but they are also caused by accidents, suicides, disease and assassinations.

The dea ...

of Joseph Rucker Lamar

Joseph Rucker Lamar (October 14, 1857 – January 2, 1916) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court appointed by President William Howard Taft. A cousin of former associate justice Lucius Lamar, he served from 1911 until hi ...

created a vacancy on the Supreme Court. Per the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

, Brandeis' nomination was subject to the advice and consent

Advice and consent is an English phrase frequently used in enacting formulae of bills and in other legal or constitutional contexts. It describes either of two situations: where a weak executive branch of a government enacts something prev ...

of the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

, which holds the determinant power to confirm or reject nominations to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Brandeis' nomination attracted significant opposition and controversy. This partially arose from his reputation and record as a lawyer of being regarded a "people's lawyer" hostile towards corporate interests. Brandeis had a record of opposing monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

, criticizing investment banks

Investment banking pertains to certain activities of a financial services company or a corporate division that consist in advisory-based financial transactions on behalf of individuals, corporations, and governments. Traditionally associated wit ...

, and advocating for workers' rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, these rights influen ...

. Concerns were raised about the "radicalism" of Brandeis. Opposition also arose from antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

due to Brandeis being the first Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

nominee to the Supreme Court of the United States. The nomination was opposed by corporate leaders, such as J. P. Morgan Jr. William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, both a former United States president and a former American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of aca ...

president, organized opposition to the nomination among leaders of the American Bar Association. Taft and six other former presidents of the American Bar Association sent a letter to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary opposing the nomination. The nomination also came into strong opposition from members of the Boston Brahmin

The Boston Brahmins or Boston elite are members of Boston's traditional upper class. They are often associated with Harvard University; Anglicanism; and traditional Anglo-American customs and clothing. Descendants of the earliest English coloni ...

, among the most prominent in opposing the nomination being A. Lawrence Lowell

Abbott Lawrence Lowell (December 13, 1856 – January 6, 1943) was an American educator and legal scholar. He was President of Harvard University from 1909 to 1933.

With an "aristocratic sense of mission and self-certainty," Lowell cut a large f ...

(the president of Harvard University) and Henry Lee Higginson

Henry Lee Higginson (November 18, 1834 – November 14, 1919) was an American businessman best known as the founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and a patron of Harvard University.

Biography

Higginson was born in New York City on November 18 ...

.

All but one member of the faculty of the Harvard Law School endorsed the nomination. Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judic ...

, among the school’s faculty, was a particularly proactive supporter of the nomination. The nomination saw liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and progessive support. In addition, many prominent members of the American Jewish

American Jews or Jewish Americans are Americans, American citizens who are Jewish, whether by Judaism, religion, ethnicity, culture, or nationality. Today the Jewish community in the United States consists primarily of Ashkenazi Jews, who desce ...

community supported the nomination.

Brandeis' nomination was subject to near-unprecedented confirmation hearings conducted by the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. The 125-day gap between his nomination and the full-Senate vote on confirming him to the court is by far the longest such gap for any U.S. Supreme Court nomination that was brought to a confirmation vote. The nomination ultimately received positive reports from both a subcommittee of the Judiciary Committee and from the full Judiciary Committee. Brandeis was confirmed to the court on June 1, 1916, in a 47–22 vote.

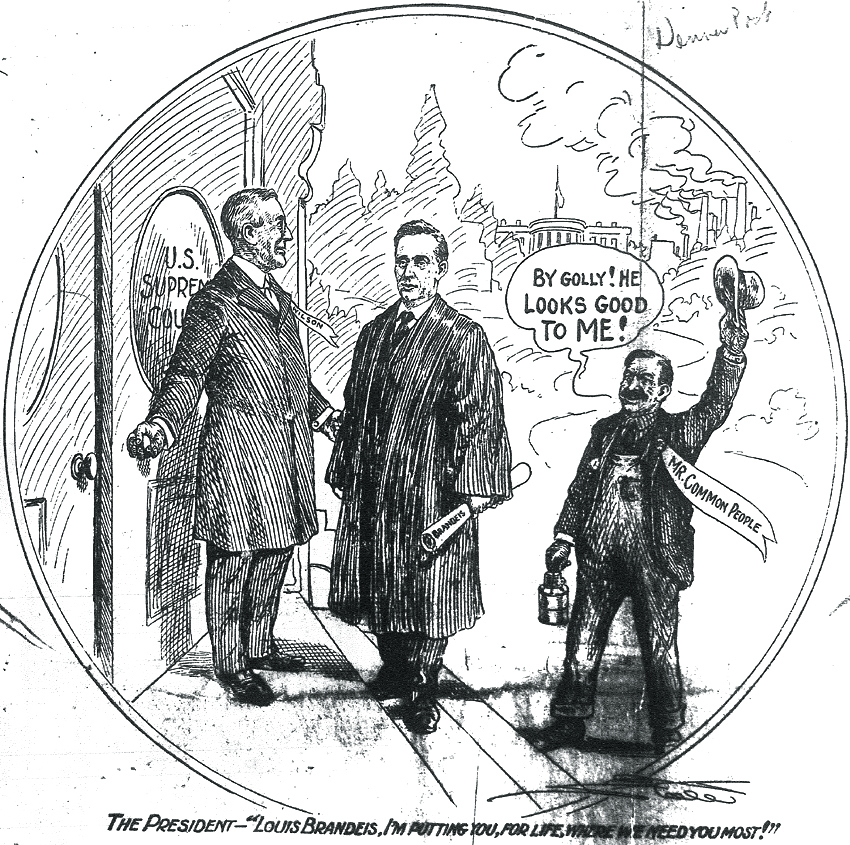

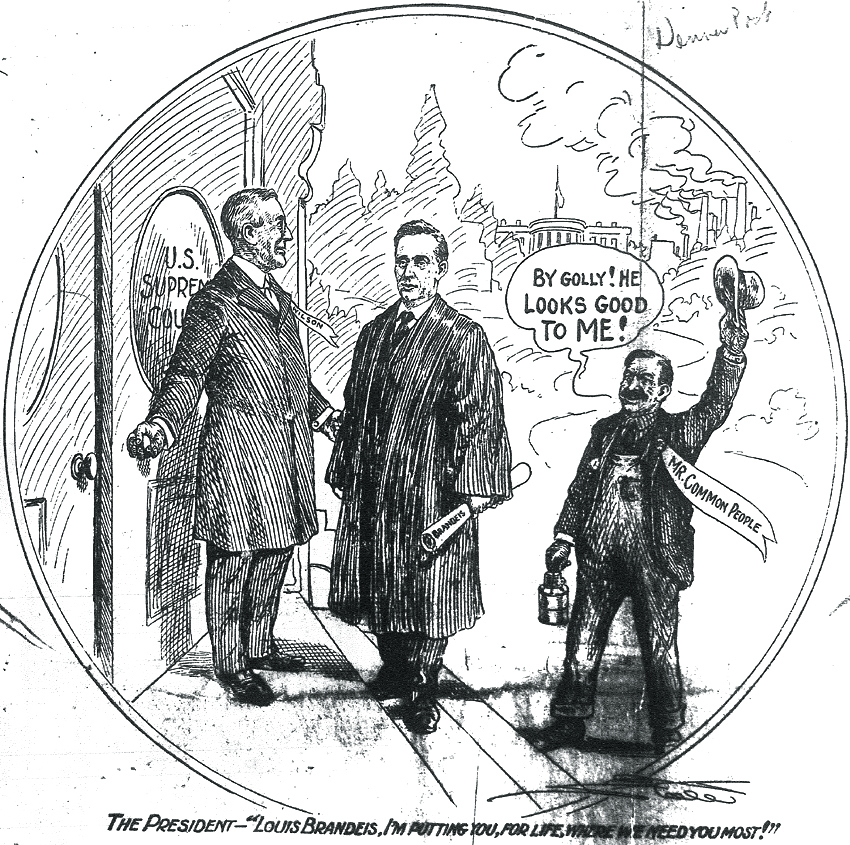

Nomination by President Wilson

On January 28, 1916, President

On January 28, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

nominated Louis Brandeis to fill the associate justice

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some sta ...

seat on the Supreme Court of the United States left vacant by the death in office

A death in office is the death of a person who was incumbent of an office-position until the time of death. Such deaths have been usually due to natural causes, but they are also caused by accidents, suicides, disease and assassinations.

The dea ...

of Joseph Rucker Lamar

Joseph Rucker Lamar (October 14, 1857 – January 2, 1916) was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court appointed by President William Howard Taft. A cousin of former associate justice Lucius Lamar, he served from 1911 until hi ...

. The nomination was then referred the Senate Committee on the Judiciary.Chilton, p. 1 Wilson's nomination of Brandeis was regarded as a great surprise. He had never come up in speculation about what individuals might fill the vacancy. It had not been expected that Wilson, up for what seemed like a difficult reelection battle eight months later in the 1916 United States presidential election, would nominate a controversial individual. It was reported that several senators gasp

Paralanguage, also known as vocalics, is a component of meta-communication that may modify meaning, give nuanced meaning, or convey emotion, by using techniques such as prosody, pitch, volume, intonation, etc. It is sometimes defined as relati ...

ed when the nomination was announced to the Senate chamber.

''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

reporting shortly after the nomination was made credited Thomas Watt Gregory

Thomas Watt Gregory (November 6, 1861February 26, 1933) was an American politician and lawyer. He was a progressive and attorney who served as US Attorney General from 1914 to 1919 under US President Woodrow Wilson.

Early life

Gregory was born ...

, the U.S. attorney general

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

, with having made the successful recommendation to Wilson that Brandeis be appointed to the court. In making his selection, Wilson ignored the tradition of informing, and usually receiving the approval, of the U.S. Senators representing the nominee's home state. In Brandeis' case, the senators representing his home state of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

were Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

senators Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge (May 12, 1850 November 9, 1924) was an American Republican politician, historian, and statesman from Massachusetts. He served in the United States Senate from 1893 to 1924 and is best known for his positions on foreign policy. ...

and John W. Weeks. In fact, the only U.S. senator that Wilson, a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, had his administration consult before announcing the selection of Brandeis was Robert La Follette

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

, a progressive member of the Republican Party. Attorney General Gregory met with La Follette days after Justice Lamar's death and inquired as to whether La Follette would consider crossing party lines to vote to confirm Brandeis, which La Follette enthusiastically declared that he would. Brandeis had only been told of his nomination several days before it was formally made.

Brandeis, dubbed the "people's lawyer", was a controversial figure for his challenging of monopolies

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

, criticism of investment banks

Investment banking pertains to certain activities of a financial services company or a corporate division that consist in advisory-based financial transactions on behalf of individuals, corporations, and governments. Traditionally associated wit ...

, his advocacy for workers' rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, these rights influen ...

, and his advocacy for protecting civil liberties. He was regarded as a "trust

Trust often refers to:

* Trust (social science), confidence in or dependence on a person or quality

It may also refer to:

Business and law

* Trust law, a body of law under which one person holds property for the benefit of another

* Trust (bus ...

buster". Brandeis was among the nation's most noted Progressive reformers. Brandeis was also the first person of Jewish descent ever nominated the Supreme Court of the United States. President Wilson had commonality with Brandeis over their skepticism of large corporate power, with Wilson having been a stronger supporter of antitrust laws than either Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

or William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, who had been his main opponents in the 1912 United States presidential election. Brandeis had been an influential advisor, political confidante, and friend of Wilson since Wilson's 1912 campaign and had shaped Wilson's "The New Freedom

The New Freedom was Woodrow Wilson's campaign platform in the 1912 presidential election, and also refers to the progressive programs enacted by Wilson during his first term as president from 1913 to 1916 while the Democrats controlled Congre ...

" agenda. When he took office in 1913, Wilson had considered appointing Brandeis as his U.S. attorney general. However, corporate executives, particularly those from the banking and legal establishment of Brandeis' native Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, launched active opposition to the appointment of Brandeis. Among motivations for this was backlash to Brandeis' legal battles against them, as well as antisemitic opposition to the prospect of Brandeis serving as the first Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

attorney general. Consequentially, Wilson had decided at that time that he would be too controversial of an appointee. However, Wilson retained a desire to appoint Brandeis to either his Cabinet or to the Supreme Court.

Taking what appeared to be a political risk with his choice surprised many, especially considering the wide view that Wilson would already have a challenge being reelected. Incumbents had had difficulty getting reelected in previous decades. Since Ulysses Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

's reelection in 1872

Events

January–March

* January 12 – Yohannes IV is crowned Emperor of Ethiopia in Axum, the first ruler crowned in that city in over 500 years.

* February 2 – The government of the United Kingdom buys a number of forts on ...

, only once had a president been elected in two consecutive elections (William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

in 1900

As of March 1 ( O.S. February 17), when the Julian calendar acknowledged a leap day and the Gregorian calendar did not, the Julian calendar fell one day further behind, bringing the difference to 13 days until February 28 ( O.S. February 15), 2 ...

). Additionally, Democrats were not viewed as favored in presidential elections at the time. Since the United States Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, the only Democratic wins in presidential elections had been Wilson's own 1912 victory, and Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

's non-consecutive victories in the 1884

Events

January–March

* January 4 – The Fabian Society is founded in London.

* January 5 – Gilbert and Sullivan's '' Princess Ida'' premières at the Savoy Theatre, London.

* January 18 – Dr. William Price at ...

and 1892

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins accommodating immigrants to the United States.

* February 1 - The historic Enterprise Bar and Grill was established in Rico, Colorado.

* February 27 – Rudolf Diesel applies fo ...

elections. Furthermore, Wilson had won the 1912 election against a divided Republican Party, whose base of support split much of its vote between the party's nominee, Taft, and the third party

Third party may refer to:

Business

* Third-party source, a supplier company not owned by the buyer or seller

* Third-party beneficiary, a person who could sue on a contract, despite not being an active party

* Third-party insurance, such as a V ...

run of Roosevelt. With a united Republican Party in the 1916 presidential election, it seemed even more possible that Wilson would be defeated.

While general political logic had caused many to see it as a surprise that Wilson would nominate such a controversial individual to the Supreme Court months before he was up for reelection as president, there may have been political calculations in his decision to nominate Brandeis. A likely motivation for Wilson's selection Brandeis to be his nominee for the Supreme Court may have been a desire to shore up his credentials as a political progressive before the upcoming 1916 presidential election. Some at the time of the nomination also believed he might also have been seeking to shore up Jewish support for his reelection, with ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper t ...

'' writing on February 10, 1916, "old-fashioned politicians" read the nomination as, "bait for the Hebrew vote at the coming election."

The nomination of a Jewish man to the Court came, notably, amid a high point in antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

in the United States. The backdrop of the era included incidents such as the recent lynching of Leo Frank

Leo Max Frank (April 17, 1884August 17, 1915) was an American factory superintendent who was convicted in 1913 of the murder of a 13-year-old employee, Mary Phagan, in Atlanta, Georgia. His trial, conviction, and appeals attracted national at ...

and the prominence of the Ku Klux Klan.

Opposition to the nomination

Brandeis' nomination ignited an intense confirmation battle. Brandeis' nomination evoked a polarized and vocal reaction. The widespread attention and intense fight over the nomination was in contrast to most preceding Supreme Court nomination processes, which had been low-key and quiet. It was considered among the most contentious nominations up to that point.

Many opponents took issue with the "radicalism" of Brandeis. The nomination quickly received strong conservative backlash. '' The Sun'' newspaper of

Brandeis' nomination ignited an intense confirmation battle. Brandeis' nomination evoked a polarized and vocal reaction. The widespread attention and intense fight over the nomination was in contrast to most preceding Supreme Court nomination processes, which had been low-key and quiet. It was considered among the most contentious nominations up to that point.

Many opponents took issue with the "radicalism" of Brandeis. The nomination quickly received strong conservative backlash. '' The Sun'' newspaper of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

expressed outrage that Brandeis, who they regarded as a radical, had been nominated for appointment to, "the stronghold of sane conservatism, the safeguard of our institutions, the ultimate interpreter of our fundamental law". Corporate leaders, such as J. P. Morgan Jr., stood in opposition to the nomination. ''The New York Times'' wrote in its front-page story after the nomination was made,

Brandeis' later successor on the court, William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often ci ...

, wrote many years later that the nomination of Brandeis "frightened the Establishment" because he was "a militant crusader for social justice." He also wrote that, "the fears of the Establishment were greater because Brandeis was the first Jew to be named to the Court."

''The New York Times'' and ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

'' were among the press outlets that most prominently opposed the nomination. The ''New York Times'' claimed that having been a noted "reformer" for so many years, Brandeis would lack the "dispassionate temperament that is required of a judge." The ''Wall Street Journals editor, Clarence W. Barron

Clarence W. Barron (July 2, 1855, in Boston, Massachusetts – October 2, 1928) was one of the most influential figures in the history of Dow Jones & Company. As a career newsman described as a "short, rotund powerhouse", he died holding the pos ...

, strongly opposed Brandeis' nomination. The ''Wall Street Journal'' wrote of Brandeis, "In all the anti-corporation agitation of the past, one name stands out... where others were radical, he was rabid."Klebanow, Diana, and Jonas, Franklin L. ''People's Lawyers: Crusaders for Justice in American History'', M.E. Sharpe (2003) ''The New York Times'' conceded that even Brandeis' harshest detractors noted that he was a remarkably skilled lawyer, but many still contended that his abilities as a lawyer did not make him suited for the Supreme Court.

The opposition of Massachusetts U.S. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge was seen as a major concern, as it had been conventional for presidents to have first received the approval of the two Senators from a Supreme Court nominee's home state before making a nomination, or to at least notify them of their intention prior to making the nomination. Wilson had not done either. Lodge may have been able to block the nomination, as senior senator from Massachusetts, had the senator invoked the customary rule of Senatorial courtesy. However, Lodge did not do so despite holding both Wilson and Brandeis in strong public disdain. While he did urge American Bar Association leadership to oppose the nomination, Lodge did not play a major role in leading the opposition to the nomination, despite many anticipating that he would. One theory that was presented for why he did not was to not imperil his reelection in the upcoming 1916 United States Senate election in Massachusetts

The 1916 United States Senate election in Massachusetts was held on November 7, 1916. Republican incumbent Henry Cabot Lodge defeated Democratic Mayor of Boston John F. Fitzgerald to win election to a fifth term.

This was the first United State ...

, fearing repercussions from Jewish and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

voters if he more actively opposed the nomination. Lodge himself had accused Wilson of only selecting Brandeis in order to win over Jewish voters in important states.

Upon the nomination's initial announcement, a number of Democratic senators voiced dissatisfaction with the nomination.

Among the nomination's most prominent opponents was A. Lawrence Lowell

Abbott Lawrence Lowell (December 13, 1856 – January 6, 1943) was an American educator and legal scholar. He was President of Harvard University from 1909 to 1933.

With an "aristocratic sense of mission and self-certainty," Lowell cut a large f ...

, the president of Harvard University. A letter circulated by Lowell received signatures from Lowell and fifty-four other influential figures including Charles Francis Adams Jr.

Charles Francis Adams Jr. (May 27, 1835 – March 20, 1915) was an American author, historian, and railroad and park commissioner who served as the president of the Union Pacific Railroad from 1884 to 1890. He served as a colonel in the Union Arm ...

, R.W. Boyden, Julian Codman

Julian Codman (September 21, 1870 – December 30, 1932), was an American lawyer who was a vigorous opponent of Prohibition who was also involved with the Anti-Imperialist League.

Early life

Codman was born in Cotuit, Massachusetts, on September ...

, Harold Jefferson Coolidge Sr., Malcolm Donald

Malcolm Donald (1877–1949) was an American lawyer, eugenicist, white nationalist, and a founder of the Pioneer Fund.

He graduated Harvard College (where he played footballStaff report (October 8, 1899). ATHLETICS AT HARVARD.; Malcolm Donald Sa ...

, A. R. Graustein, Patrick Tracy Jackson, Augustus Peabody Loring, Francis Peabody, William Lowell Putnam

William Lowell Putnam II (November 22, 1861 – June 1923) (more commonly known as William Putnam, Sr.) was an American lawyer and banker.

Putnam was the son of George and Harriet (Lowell) Putnam. He graduated from Harvard in 1882, and proc ...

, Henry Lee Shattuck, and many other notable Boston Brahmin

The Boston Brahmins or Boston elite are members of Boston's traditional upper class. They are often associated with Harvard University; Anglicanism; and traditional Anglo-American customs and clothing. Descendants of the earliest English coloni ...

s. Lowell sent the signed letter to his close friend Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, who entered the letter into the '' Congressional Record'' and then presented a copy to Senator William E. Chilton

William Edwin Chilton (March 17, 1858November 7, 1939) was a United States senator from West Virginia. Born in St. Albans, West Virginia, Colesmouth, Virginia (now St. Albans, West Virginia), he attended public and private schools and graduated ...

, who was the chairman of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary (Judiciary Committee) subcommittee that was undertaking the initial review and hearings on the nomination.

The campaign against Brandeis' confirmation received a large amount of its organizing and fundraising from Boston Brahmin figure Henry Lee Higginson

Henry Lee Higginson (November 18, 1834 – November 14, 1919) was an American businessman best known as the founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and a patron of Harvard University.

Biography

Higginson was born in New York City on November 18 ...

, a longtime political foe of Brandeis who had earlier helped to finance an antisemitic campaign that contributed to the shelving of Brandeis' potential appointment by Wilson as U.S. attorney general.

Former president William Howard Taft strongly opposed the nomination. Taft's opposition, in part, had also been perhaps motivated by the fact that Taft had held out hope that Wilson might disregard partisan affiliations and appoint him to court. Taft, within days of the nomination being made, began organizing opposition to it among the leadership of the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of aca ...

. Taft viewed the nomination as, "an evil disgrace". Taft, at one point, wrote,

Many southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats wi ...

voiced opposition. This was, in part, due to many of them having expected that Justice Lamar, from the southern state of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, would be replaced by a fellow southerner. Edward M. House reportedly expressed suspicion that some southern senators were concerned that Brandeis might attempt to undo the separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protec ...

doctrine.

Role of antisemitism

A factor in a number of senators' and others' opposition to Brandeis' nomination was antisemitism, though few senators publicly voiced their antisemitic motivations. However, the contribution of antisemitism to the opposition Brandeis faced was largely an open secret at the time. With attitudes at the time towards Judaism, Brandeis' religion alone could rightfully be seen as a major obstacle to his confirmation. While few ''publicly'' made antisemitic declarations about the nomination, a number of senators and other notable individuals opposed to the nomination sent private communications opposing Brandeis' confirmation that have since become publicly known which confirm that the speculation of antisemitic motives among some prominent opponents was accurate. Among individuals who sent antisemitic communications that have since publicly surfaced are Senator Henry Cabot Lodge. A. Lawrence Lowell, among the most prominent opponents of the nomination is regarded by many to have been an antisemite. As president of Harvard, Lowell would later attempt to impose aJewish quota

A Jewish quota was a discriminatory racial quota designed to limit or deny access for Jews to various institutions. Such quotas were widespread in the 19th and 20th centuries in developed countries and frequently present in higher education, o ...

capping the number of Jews that would be granted admission to the University. However, while many believed Lowell's opposition to Brandeis was rooted in his antisemitism, Brandeis himself viewed Lowell's opposition as driven by social class prejudice, writing so in private. Antisemitism is a potential factor in many Southern Democrats voicing initial opposition to the nomination. Antisemitism is seen as a key factor in the decision for the unprecedented public Senate Judiciary Committee hearings held on Brandeis' confirmation. Throughout the confirmation battle, Brandeis downplayed his religion, even rejecting an offer for there to be an effort to collect the signatures of Jewish lawyers in support of his confirmation.

George Woodward Wickersham

George Woodward Wickersham (September 19, 1858 – January 25, 1936) was an American lawyer and Attorney General of the United States in the administration of President William H. Taft. He returned to government to serve in appointed positi ...

, the president of the New York City Bar Association

The New York City Bar Association (City Bar), founded in 1870, is a voluntary association of lawyers and law students. Since 1896, the organization, formally known as the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, has been headquartered in a ...

and the former U.S. attorney general under Taft, attacked supporters of Brandeis' nomination as, "A bunch of Hebrew uplifters." William F. Fitzgerald, a notable conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

Boston Democrat and a longtime political opponent of Brandeis, wrote that, "the fact that a slimy fellow of this kind by his smoothness and intrigue, together with his Jewish instinct can be appointed to the Court should teach an object lesson" to true Americans.

Former president William Howard Taft sent a four-page letter to journalist Gus Karger, who was Jewish himself, that accused Brandeis of having only recently embraced his Judaism and adopted zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

somehow as an unsuccessful ploy to get appointed as attorney general of the United States. Despite this letter invoking Brandeis' Judaism critically, Taft is not believed to have been an antisemite, having been regarded to have enjoyed close relations with the Jewish community in his native city of Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

; having had a number of Jewish political confidants; and notably having, as president, appointed Julian Mack

Julian William Mack (July 19, 1866 – September 5, 1943) was a United States circuit judge of the United States Commerce Court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, the United States Circuit Courts for the Seventh Circu ...

as the first Jewish federal judge on a United States court of appeals

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two f ...

. Additionally, Taft was reportedly dismayed with George Wickersham's comments.

Opponents utilized antisemitic stereotypes

In social psychology, a stereotype is a generalized belief about a particular category of people. It is an expectation that people might have about every person of a particular group. The type of expectation can vary; it can be, for example ...

. For instance, some cast Brandeis, who actually conducted much of his legal work pro bono, as "money grubbing". This invoked economic antisemitism

Economic antisemitism is antisemitism that uses stereotypes and canards that are based on negative perceptions or assertions of the economic status, occupations or economic behaviour of Jews, at times leading to various governmental policies and ...

. Many of those same opponents, somewhat contradictorily, accused Brandeis of also being a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

.

Prominent supporters of the nomination

Throughout the confirmation fight, President Wilson stood by his nominee, and Brandeis' confirmation was regarded as a significant victory for Wilson. The president called Brandeis a, "friend of all just men and a lover of the right."

Throughout the confirmation fight, President Wilson stood by his nominee, and Brandeis' confirmation was regarded as a significant victory for Wilson. The president called Brandeis a, "friend of all just men and a lover of the right." Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

politicians expressed support for the nomination, including many progressives in the Republican Party and reform-minded members of Wilson's Democratic Party. The nomination had many prominent and influential supporters, including a number of noted attorneys, social workers, and reformers with whom Brandeis had previously worked.Todd, Alden L. ''Justice on Trial: The Case of Louis D. Brandeis'', McGraw-Hill (1964)., p. 208

Harvard Law School faculty, with one non-participant, gave a public endorsement to Brandeis' nomination. This was, in large part, due to the work of Brandeis' friend and intimate political ally Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judic ...

, who had been appointed to the law school's faculty the previous year in part upon a strong recommendation by Brandeis himself to Dean Roscoe Pound

Nathan Roscoe Pound (October 27, 1870 – June 30, 1964) was an American legal scholar and educator. He served as Dean of the University of Nebraska College of Law from 1903 to 1911 and Dean of Harvard Law School from 1916 to 1936. He was a membe ...

. Frankfurter mobilized nine of his fellow ten fellow faculty to endorse Brandeis' nomination. Frankfurter wrote, throughout the four-month period before Brandeis was confirmed, a number of editorial pieces, letters, and articles in magazines in support of Brandeis' nomination. This included an unsigned editorial published by on February 5, 1916, in ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' is an American magazine of commentary on politics, contemporary culture, and the arts. Founded in 1914 by several leaders of the progressive movement, it attempted to find a balance between "a liberalism centered in hu ...

'' reviewing the accomplishments of Brandeis and praising his judicial qualities and hailing Brandeis as seeking, "to make the great reconciliation between order and justice." At the urging of Frankfurter, Harvard Law School Dean Pound wrote a letter to Senator Chilton in praise of Brandeis' appointment. Similarly, such a letter was also written to Chilton and the subcommittee by former Harvard University President Charles W. Eliot

Charles William Eliot (March 20, 1834 – August 22, 1926) was an American academic who was president of Harvard University from 1869 to 1909the longest term of any Harvard president. A member of the prominent Eliot family of Boston, he transfo ...

, a highly regarded figure. Harvard Law School Dean Roscoe Pound testified during he Judiciary Committee hearings that, "Brandeis was one of the great lawyers," and predicted that he would one day rank "with the best who have sat upon the bench of the Supreme Court."

Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the te ...

(the editor of ''The New Republic'' and ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'') and the editors of ''La Follette's Weekly

''The Progressive'' is a left-leaning American magazine and website covering politics and culture. Founded in 1909 by U.S. senator Robert M. La Follette Sr. and co-edited with his wife Belle Case La Follette, it was originally called ''La Follett ...

'' helped to coordinate a publicity campaign in support of the nomination. Additionally, notable individuals that wrote letters to the Senate Judiciary Committee in support of Brandeis' nomination included Newton Baker

Newton Diehl Baker Jr. (December 3, 1871 – December 25, 1937) was an American lawyer, Georgist,Noble, Ransom E. "Henry George and the Progressive Movement." The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 8, no. 3, 1949, pp. 259–269. w ...

(the reform-minded mayor of Cleveland), writer Norman Hapgood

Norman Hapgood (March 28, 1868 – April 29, 1937) was an American writer, journalist, editor, and critic, and an American Minister to Denmark.

Biography

Norman Hapgood was born March 28, 1868 in Chicago, Illinois to Charles Hutchins Hapgood ( ...

, Walter Lippmann, Henry Morgenthau Sr. (former ambassador of the United States to the Ottoman Empire), labor activist Frances Perkins, and Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise

Stephen Samuel Wise (March 17, 1874 – April 19, 1949) was an early 20th-century American Reform rabbi and Zionist leader in the Progressive Era. Born in Budapest, he was an infant when his family immigrated to New York. He followed his fath ...

. Morgenthau was an especially involved proponent of the nomination.

On February 8, 1916, Samuel Seabury

Samuel Seabury (November 30, 1729February 25, 1796) was the first American Episcopal bishop, the second Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, and the first Bishop of Connecticut. He was a leading Loyalist ...

(associate judge of the New York Court of Appeals) delivered remarks to the Far Western Traveler's Association at the Hotel Astor

Hotel Astor was a hotel on Times Square in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Built in 1905 and expanded in 1909–1910 for the Astor family, the hotel occupied a site bounded by Broadway, Shubert Alley, and 44th and 45th Str ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

. An excerpt of the speech was made available to the media. Seabury declared that, "the country is to be congratulated upon the nomination of Mr. Brandeis for associate justice of the Supreme Court. It is a most welcome nomination. His appointment would result in a benefit to the country and to the Supreme Court itself."

Upon the nomination being made, ''The New York Times'' speculated that, "the appointment might appeal to advocates of religious tolerance because Mr. Brandeis is of Jewish blood and a leader in the Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

movement." Many prominent Jewish leaders, such as Jacob Schiff

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Ja ...

, organized in support of Brandeis' nomination. Jewish businessman Nathan Straus

Nathan Straus (January 31, 1848 – January 11, 1931) was an American merchant and philanthropist who co-owned two of New York City's biggest department stores, R. H. Macy & Company and Abraham & Straus. He is a founding father and namesake f ...

convinced journalist Arthur Brisbane

Arthur Brisbane (December 12, 1864 – December 25, 1936) was one of the best known American newspaper editors of the 20th century as well as a real estate investor. He was also a speech writer, orator, and public relations professional who coach ...

to author an editorial in the ''New York Evening Journal

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'' supporting the nomination. Among some of the Jewish leaders that supported the nomination were some that had previously been critical of Brandeis.

Judiciary Committee review

Since 1828, many Supreme Court nominations have been sent to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary for review. Since a Senate rule was adopted in 1868 requiring all nomination to be sent to an appropriate standing committee, it has been practice that nearly all Supreme Court nominations have been reviewed by the Judiciary Committee. However, before Brandeis, reviews by the Judiciary Committee of nominations had been brief and closed to the public. Contrarily to previous practice, the review of Brandeis' nomination lasted months and featured public hearings. It was not until June 1, 1916, more than four months after the nomination was made, that the Judiciary Committee ended its review. Brandeis' Judiciary Committee review featured hearings. The Judiciary Committee's hearings on Brandeis nomination took place over a four-month period. Before Brandeis' nomination, there had been only one recorded instance in which hearings had been conducted as part of a Judiciary Committee review of a Supreme Court nominee, with two closed door hearings having been held on December 16 and 17, 1873 on the nomination ofGeorge Henry Williams

George Henry Williams (March 26, 1823April 4, 1910) was an American judge and politician. He served as chief justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, was the 32nd Attorney General of the United States, and was elected Oregon's U.S. senator, and serv ...

.

The purported reasons given for why there were to be hearings held on Brandeis' nomination were concerns about assertions that he was a controversial liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

, a supposedly dangerous radical, and that he might lack "judicial temperament". However, actual motivations for holding hearings on Brandeis' nomination came from both antisemitism against Brandeis and from disdain for the public-interest work that had earned Brandeis a reputation as the "People's Lawyer". Opponents of Brandeis' nomination publicly played down antisemitic motivations. Senator Lee Slater Overman

Lee Slater Overman (January 3, 1854December 12, 1930) was a Democratic U.S. senator from the state of North Carolina between 1903 and 1930. He was the first US Senator to be elected by popular vote in the state, as the legislature had appointe ...

claimed that the hearings were needed because the nomination had come as "a great surprise," and that senators therefore needed "to get all the facts available about the nominee." The ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television a ...

'' speculated that the hearings were going to be held because, "enemies of Mr. Brandeis think one of the surest ways of beating him is to hold a series of hearings.". The ''International News Service

The International News Service (INS) was a U.S.-based news agency (newswire) founded by newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst in 1909.

'' believed that the unprecedented move to hold open hearings on a Supreme Court nomination was due to, "the precedent-destroying fact that Mr. Brandeis is a Jew". Brandeis' religion was an unspoken factor in the hearings, however. The published testimony and reports from the hearings show only one instance when Brandeis' Jewish faith was given any mention, with Boston-based lawyer Francis Peabody on March 2, 1916, testifying that he had not known Brandeis' faith in a past instance, and that it "made no difference as far as my opinion of him goes" when Brandeis' faith was later publicized.

Unlike preceding Supreme Court confirmation reviews by the Judiciary Committee, the hearings held into Brandeis took on characteristics of a trial

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal ...

. Brandeis was accused of a number of charges against his character, and advocates argued both sides of these cases. Witnesses

In law, a witness is someone who has knowledge about a matter, whether they have sensed it or are testifying on another witnesses' behalf. In law a witness is someone who, either voluntarily or under compulsion, provides testimonial evidence, e ...

and evidence were presented. The members of the subcommittee and later the full Judiciary Committee stood to deliver what amounted to a verdict on the charges against Brandeis as they related to his suitability for the court. In the entire hearing process, forty-six witnesses were heard. Over the course of the hearings, it was unclear whether Brandeis' nomination would ultimately succeed or fail. Proponents and opponents of Brandeis' confirmation alike hoped to use the hearings to persuade senators who were undecided about the nomination. Brandeis refused to personally testify

In law and in religion, testimony is a solemn attestation as to the truth of a matter.

Etymology

The words "testimony" and "testify" both derive from the Latin word ''testis'', referring to the notion of a disinterested third-party witness.

La ...

in the hearings. However, he was involved in guiding what amounted to a defense, frequently providing documents, records, and advice to those who were advocating for him in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

The arguments made against Brandeis largely did not focus on the ideological agenda he might pursue but instead accused Brandeis of past ethical misconduct.

Subcommittee hearings

Within a day of the nomination being made, a Judiciary Committee subcommittee was formed to investigate the nomination and proceeded to schedule for hearings to be held on the nomination. The subcommittee was chaired by Democrat William E. Chilton, with its remaining membership consisting of Democrats Duncan U. Fletcher, Thomas J. Walsh and Republicans Clarence D. Clark and Albert Cummins. The hearings held by the subcommittee were open to the public, unlike the hearings for George Henry Williams, which had been closed door. On January 31, the Judiciary Committee officially referred the nomination to the subcommittee. Brandeis refused to personally testify, but provided assistance and cooperation with those who were advocating on his behalf in the hearings. At the time that the hearings began in early February, Brandeis stayed inBoston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

, and declared to reporters, "I have nothing whatever to say; I have not said anything and will not."

The statements, documents, and questioning of the hearings amounted to 1,590 pages of documents. Forty-three witness

In law, a witness is someone who has knowledge about a matter, whether they have sensed it or are testifying on another witnesses' behalf. In law a witness is someone who, either voluntarily or under compulsion, provides testimonial evidence, e ...

es testified before the subcommittee, with testimony being recorded by a stenographer and subsequently printed in a 1,316 page volume. Witnesses testified both in support and against the nomination. Hearings were held on February 9 and 10, February 15–18, February 24–26, February 29–March 4, March 6–8, and March 14 and 15. These nineteen days of hearings are far more than the number of days of hearings that have been given to any other Supreme Court nominee. On February 16, Republican John D. Works was added to the subcommittee in the place of Senator Clark.

The hearings before the subcommittee saw prominent witnesses brought in to cast Brandeis as unfit to serve on the court. Opponents did not challenge Brandeis' legal credentials, but rather that attacked his reputation. Negative testimony was given that Brandeis was unprofessional, unethical, unfit in character. Negative testimony was also given that Brandeis was an activist incapable of being an impartial justice. Supporters of Brandeis countered that these were unfounded attacks lodged by "privileged interests". Brandeis' anti-corporate record was attacked. The hearing looked at years of cases, litigation, activities of Brandeis, and other matters that were considered consequential at the time. Chief among those arguing before the committee in opposition to Brandeis' confirmation was former Harvard president A. Lawrence Lowell, who effectively took on the role of leading the opposition. Austen George Fox was retained to act in a role akin to a prosecutor against Brandeis. At the request of the Judiciary Committee, Judge George W. Anderson took on the role of arguing the case in support of Brandeis' confirmation, a role akin to a defense attorney.

Among those to testify were Clarence W. Barron, Moorfield Storey

Moorfield Storey (March 19, 1845 – October 24, 1929) was an American lawyer, anti-imperial activist, and civil rights leader based in Boston, Massachusetts. According to Storey's biographer, William B. Hixson, Jr., he had a worldview that embod ...

, and Sherman L. Whipple. Barron made negative accusations against Brandeis, accusing him of having violated professional ethics as a lawyer by representing both sides in a case related to the United Shoe Machinery Company. Storey criticized Brandeis and Whipple gave a testimony positive towards Brandeis.

In March, at the close of the hearings by the subcommittee, seven former American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of aca ...

presidents ( Joseph H. Choate Jr., Peter Meldrim, Elihu Root, Francis Rawle, Moorfield Storey, and William Howard Taft) sent a written statement to the committee that harshly opposed Brandeis' nomination. The letter declared,

Subcommittee report

On April 1, 1916, by a party-line vote of 3–2 (with all Democrats voting to report favorably and all Republicans voting against reporting favorably), the subcommittee voted to give a favorable report on Brandeis' nomination to the full Judiciary Committee. On April 3, the subcommittee issued their favorable majority report on the nomination written by Senator Chilton to the full Judiciary Committee. Senator Fletcher concurred with the majority report, while Senator Walsh filed a separate favorable report, having disagreed with Chilton's majority report on several facts. Senators Cummins and Works wrote a minority report of the subcommittee against the nomination. The minority report argued that the twelve specific charges that were made against Brandeis cast strong doubt on his ethics and integrity and argued that there would therefore be possible impropriety in appointing him the Supreme Court. One of the numerous accusations made against Brandeis during the hearings was that he had advised and assisted Samuel D. Warren in a breach of trust in fraud of his brother Edward P. Warren. Clinton's majority report found that charge to be, "wholly unfounded and recognized to be by the leading counsel for Edward P. Warren in the suit concerning this trust," and noted that, "the propriety of Mr. Brandeis's conduct in this case was also recognized by one of his leading opponents who was counsel for other beneficiaries of the trust". On the accusation that Brandeis was working for the New York, New Haven, & Hartford Railroad to wreck the New York & New England Railroad Company, the majority report opined that, "the facts do not sustain this charge". The United Shoe Machinery Company had accused Brandeis of unprofessional conduct in obtaining information while associated with the company and later using this information in the interest of other clients. This related to their tying-clause system, However, the majority report emphasized the fact that three and a half years had elapsed before Brandeis had advised any clients on this subject, and found that he made no use of confidential information and instead had used facts that, "seem to have been public property well known to the shoe manufacturers". There were many other allegations and insinuations of improper and unprofessional conduct by Brandeis that the majority report found unsupported.Full committee hearings

After the subcommittee ended hearings in March, the full committee began further hearings in May. At one point Brandeis considered testifying, but ultimately did not. During the time of these hearings, Brandeis personally met in

After the subcommittee ended hearings in March, the full committee began further hearings in May. At one point Brandeis considered testifying, but ultimately did not. During the time of these hearings, Brandeis personally met in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

at the personal residence of the publisher of ''Harper's Weekly

''Harper's Weekly, A Journal of Civilization'' was an American political magazine based in New York City. Published by Harper & Brothers from 1857 until 1916, it featured foreign and domestic news, fiction, essays on many subjects, and humor, ...

'' with two senators who were on the fence about his nomination.

These hearings featured many businessmen's testimony against Brandeis' nomination. During this time, enemies of the nomination also circulated a document with false accusations of involvement by Brandeis in legal efforts to retrieve love letters sent by Wilson to a woman in Bermuda. It appeared, for a time, that the Judiciary Committee was poised to report negatively on the nomination. By mid-May it seemed that the committee would report without a recommendation, with reports being made that the Judiciary Committee had been unable to agree on approving a favorable report and that several Democratic members of the committee were against a favorable report and would instead support a motion to return the nomination to the Senate without making a full recommendation.

Committee Chairman Charles Allen Culberson was encouraged by Attorney General Gregory to request that Wilson provide a summary of reasons why he had nominated Brandeis to begin with. Wilson sent a letter May 4, 1916 which was received the following day. The letter outlined his reasons and declared that, "no one is more imbued to the very heart of our American ideals of justice and equality of opportunity...he is a friend of all just men and a lover of the right; and he knows more than how to talk about the right – he knows how to set it forward in the face of its enemies." The letter also urged the committee to promptly vote favorably on the nomination. The letter was entered into the ''Congressional Record'' on May 9, 1916.

Committee report

On May 24, 1916, in a 10–8 vote, the Judiciary Committee voted to report favorably on Brandeis' nomination. The vote was a party-line vote, with all Democrats voting in support of reporting favorably, and all Republicans voting against it. While Senator Albert B. Cummins was physically absent, his vote against the nomination was allowed to be counted.

The committee's majority report defended Brandeis against allegations that had been raised of alleged misconduct. It also made a point that Brandeis would not be the first Supreme Court judge appointed amid what it contended were tense and unjust attacks. It also claimed that letters and petitions in support of the nomination significantly outweighed the opposition raised to the nomination.

The committee's minority report alleged that twelve allegations of misconduct by Brandeis had been sustained by evidence and that it had been proven that Brandeis had a bad reputation among lawyers of the Boston bar. It argued that Brandeis had his integrity more seriously questioned than any prior justice appointed to the Supreme Court and that his nomination had lowered the standard for appointment to the court.

After the vote, ''The New York Times'' wrote,

In a memorable editorial, ''The New York Times'' continued to voice the opinion that Brandeis was suited not for the courts, but was rather suited for the legislature. It complained that Brandeis was,

''The New York Times'' also wrote,

On May 24, 1916, in a 10–8 vote, the Judiciary Committee voted to report favorably on Brandeis' nomination. The vote was a party-line vote, with all Democrats voting in support of reporting favorably, and all Republicans voting against it. While Senator Albert B. Cummins was physically absent, his vote against the nomination was allowed to be counted.

The committee's majority report defended Brandeis against allegations that had been raised of alleged misconduct. It also made a point that Brandeis would not be the first Supreme Court judge appointed amid what it contended were tense and unjust attacks. It also claimed that letters and petitions in support of the nomination significantly outweighed the opposition raised to the nomination.

The committee's minority report alleged that twelve allegations of misconduct by Brandeis had been sustained by evidence and that it had been proven that Brandeis had a bad reputation among lawyers of the Boston bar. It argued that Brandeis had his integrity more seriously questioned than any prior justice appointed to the Supreme Court and that his nomination had lowered the standard for appointment to the court.

After the vote, ''The New York Times'' wrote,

In a memorable editorial, ''The New York Times'' continued to voice the opinion that Brandeis was suited not for the courts, but was rather suited for the legislature. It complained that Brandeis was,

''The New York Times'' also wrote,

Confirmation vote

On June 1, 1916, the Senate voted 47–22 to confirm Brandeis. The 125-day period between Wilson's nomination of Brandeis and the vote to confirm him is the longest time between a nomination of the United States Supreme Court nominee and a vote on confirmation by a significant margin. No debate was held before the vote. A compromise had been struck in which the Senate would forgo debate but would authorize the publication of the majority and minority reports of the Judiciary Committee.: * * There was a large degree of pairing between absent senators, in which senators who would have voted differently from one another if present agreed to both be absent from the vote, thereby canceling out the absence of the senator with which they were paired. Many of the Republican senators absent for the vote were instead busying themselves with preparations for the 1916 Republican National Convention inChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

. It is possible that some Republican senators desired to be absent so that they could avoid voting against Brandeis, who they opposed, without outright voting against him, which they feared could lose them support from Jewish voters.

The three Republican senators that cast votes in support of confirming Brandeis (Robert M. La Follette, George W. Norris, and Miles Poindexter

Miles Poindexter (April 22, 1868September 21, 1946) was an American lawyer and politician. As a Republican Party (United States), Republican and briefly a Progressive Party 1912 (United States), Progressive, he served one term as a United States ...

) were all staunch political progressives.

Despite there being prominent Ku Klux Klan-inspired antisemitism at the time, the vote was mostly a party-line vote. None of the Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats, historically sometimes known colloquially as Dixiecrats, are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States. Southern Democrats were generally much more conservative than Northern Democrats wi ...

that were present voted against the nomination, despite there being complex politics in the South regarding Jewish Americans. Francis G. Newlands was sole Democratic senator to vote against the nomination. In explaining his vote against Brandeis' confirmation, Newlands characterized Brandeis as a talented, "publicist and propogandist," and remarked, "I do not regard him as a man of judicial temperament, and for that reason I have voted against his confirmation". Newlands' vote against confirming Brandeis had come as a surprise. The support Brandeis received from all other Democrats present for the vote was, perhaps, reflective of the power the Wilson had in his party. Wilson was seen as helping the Democratic Party win the U.S. Senate, as they had won control of the Senate in 1912, alongside Wilson's victory, and had won five more seats in the midterm election

Apart from general elections and by-elections, midterm election

refers to a type of election where the people can elect their representatives and other subnational officeholders (e.g. governor, members of local council) in the middle of the term ...

of 1914

This year saw the beginning of what became known as World War I, after Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, heir to the Austrian throne was Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, assassinated by Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip. It als ...

.

Pairing of absent senators

There was a large degree of pairing between absent senators, in which senators who would have voted differently from one another if present agreed to both be absent from the vote, thereby canceling out the absence of the senator with which they were paired. Twenty-seven Senators were absent from the vote. The only three absent senators that were not paired with another absent senator were SenatorsJames Paul Clarke

James Paul Clarke (August 18, 1854 – October 1, 1916) was a United States Senator and the 18th Governor of Arkansas as well as a white supremacist.

Biography

Clarke was born in Yazoo City, Mississippi. His father died when Clarke was seven y ...

(D– AR), George P. McLean

George Payne McLean (October 7, 1857 – June 6, 1932) was the 59th Governor of Connecticut, and a United States senator from Connecticut.

Biography

McLean was born in Simsbury, Connecticut, one of five children of Dudley B. McLean and Mary ( ...

(R– CT), and Lawrence Yates Sherman (R– IL).

Aftermath

Brandeis was sworn in as an associate justice on June 5, 1916, becoming the first Jewish member of the court. His investiture (swearing-in) ceremony was noted to have drawn a large and distinguished attendance in comparison to those that had recently preceded it. For his investiture, the Supreme Court chamber was filled with spectators, including several Cabinet members, members of the U.S. Senate, and members of the U.S. House of Representatives. Brandeis' confirmation was regarded as a significant victory for President Wilson, who remarked, "I never signed any commission with such satisfaction as I signed his." Brandeis joining the court as its first Jewish justice is regarded to be a milestone in Jewish American history. It was also perhaps a milestone marking the start to an end political leaders blocking the appointment of Jews from being appointed to higher political positions. Brandeis served on the court for twenty-three years. On the court, Brandeis continued to be a strong voice for progressivism. He is widely regarded as being among most important and the most influential justices in the history of the United States Supreme Court, often being ranked among the very "greatest" justices in the court's history. Upon his 1939 retirement from the court, ''The New York Times'', which had so strongly opposed his nomination, issued great praise to his tenure on the court, hailing him as, "one of the great judges of our times." Former presidentWilliam Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

, who spoke out against Brandeis' nomination, went on to serve on the court with him as chief justice. Taft respected and liked Brandeis when they served together on the court. George Sutherland

George Alexander Sutherland (March 25, 1862July 18, 1942) was an English-born American jurist and politician. He served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938. As a member of the Republican Party, he also repre ...

, a senator who voted against Brandeis' nomination, also served with Brandeis as a fellow associate justice. Brandeis' close friend and ally Felix Frankfurter, who supported the nomination, was appointed to the court in 1939, very shortly before Brandeis' retirement.