Lord Willingdon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Freeman Freeman-Thomas, 1st Marquess of Willingdon (12 September 1866 – 12 August 1941), was a

Willingdon was on 17 February 1913 appointed as the Crown Governor of Bombay, replacing the Lord Sydenham of Combe, and to mark this event, Willingdon was on 12 March 1913 honoured with induction into the

Willingdon was on 17 February 1913 appointed as the Crown Governor of Bombay, replacing the Lord Sydenham of Combe, and to mark this event, Willingdon was on 12 March 1913 honoured with induction into the  In 1917, the year before Willingdon's resignation of the governorship, a severe famine broke out in the

In 1917, the year before Willingdon's resignation of the governorship, a severe famine broke out in the

It was announced on 5 August 1926 that George V had, by commission under the

It was announced on 5 August 1926 that George V had, by commission under the  The

The

by Lorna Lloyd. Willingdon arrived at

He had not been Governor General of Canada for five years before Willingdon received word that he was to be sent back to India as that country's viceroy and governor general. After being appointed to the

He had not been Governor General of Canada for five years before Willingdon received word that he was to be sent back to India as that country's viceroy and governor general. After being appointed to the

It was also by Willingdon's hand, as Governor-in-Council, that the Lloyd Barrage was commissioned, seeing £20 million put into the construction of the barrage across the mouth of the

It was also by Willingdon's hand, as Governor-in-Council, that the Lloyd Barrage was commissioned, seeing £20 million put into the construction of the barrage across the mouth of the

;Appointments

* 18 July 191131 January 1913: Lord-in-Waiting to His Majesty the King

* 12 March 1913 – 21 July 1941:

;Appointments

* 18 July 191131 January 1913: Lord-in-Waiting to His Majesty the King

* 12 March 1913 – 21 July 1941:

Website of the Governor General of Canada entry for Freeman Freeman-Thomas

The Canadian Encyclopedia entry for Freeman Freeman-Thomas

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Willingdon, Freeman Freeman-Thomas, 1st Marquess of Viceroys of India 1930s in British India Governors of Bombay 1866 births 1941 deaths Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Governors General of Canada Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire Liberal Party (UK) Lords-in-Waiting Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports Freeman-Thomas, Freeman Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire Freeman-Thomas, Freeman Freeman-Thomas, Freeman UK MPs who were granted peerages Scouting and Guiding in India Freeman-Thomas, Freeman English cricketers Cambridge University cricketers Sussex cricketers Chief Scouts of Canada Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Marquesses of Willingdon Barons created by George V Viscounts created by George V Peers created by Edward VIII Burials at Westminster Abbey People educated at Eton College

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

politician and administrator who served as Governor General of Canada

The governor general of Canada (french: gouverneure générale du Canada) is the federal viceregal representative of the . The is head of state of Canada and the 14 other Commonwealth realms, but resides in oldest and most populous realm, t ...

, the 13th since Canadian Confederation

Canadian Confederation (french: Confédération canadienne, link=no) was the process by which three British North American provinces, the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, were united into one federation called the Canada, Dom ...

, and as Viceroy and Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, the country's 22nd.

Freeman-Thomas was born in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and educated at Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

and then the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

before serving for 15 years in the Sussex Artillery. He then entered the diplomatic and political fields, acting as aide-de-camp to his father-in-law when the latter was Governor of Victoria

The governor of Victoria is the representative of the monarch, King Charles III, in the Australian state of Victoria. The governor is one of seven viceregal representatives in the country, analogous to the governors of the other states, and the ...

and, in 1900, was elected to the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

. He thereafter occupied a variety of government posts, including secretary to the British prime minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

and, after being raised to the peerage as Lord Willingdon, as Lord-in-waiting

Lords-in-waiting (male) or baronesses-in-waiting (female) are peers who hold office in the Royal Household of the sovereign of the United Kingdom. In the official Court Circular they are styled "Lord in Waiting" or "Baroness in Waiting" (without ...

to King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

. From 1913, Willingdon held gubernatorial and viceregal offices throughout the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, starting with the governorship of Bombay and then the governorship of Madras, before he was in 1926 appointed as the Governor-General of Canada to replace the Viscount Byng of Vimy

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

, occupying the post until succeeded by the Earl of Bessborough

Earl of Bessborough is a title in the Peerage of Ireland. It was created in 1739 for Brabazon Ponsonby, 2nd Viscount Duncannon, who had previously represented Newtownards and County Kildare in the Irish House of Commons. In 1749, he was given ...

in 1931. Willingdon was immediately thereafter appointed as Viceroy and Governor-General of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

to replace Lord Irwin

Edward Frederick Lindley Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax, (16 April 1881 – 23 December 1959), known as The Lord Irwin from 1925 until 1934 and The Viscount Halifax from 1934 until 1944, was a senior Conservative Party (UK), British Conservat ...

(later created Earl of Halifax), and he served in the post until succeeded by the Marquess of Linlithgow

Marquess of Linlithgow, in the County of Linlithgow or West Lothian, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 23 October 1902 for John Hope, 7th Earl of Hopetoun. The current holder of the title is Adrian Hope.

This ...

in 1936.

After the end of his viceregal tenure, Willingdon was installed as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

The Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports is a ceremonial official in the United Kingdom. The post dates from at least the 12th century, when the title was Keeper of the Coast, but may be older. The Lord Warden was originally in charge of the Cinqu ...

and was elevated in the peerage as the Marquess of Willingdon. After representing Britain at a number of organisations and celebrations, Willingdon died in 1941 at his home in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, and his ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

Early life and education

Freeman Thomas was born the only son of Freeman Frederick Thomas, an officer in the rifle brigade of Ratton and Yapton, and his wife, Mabel, daughter of Henry Brand,Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury

The Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury is the official title of the most senior whip of the governing party in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Today, any official links between the Treasury and this office are nominal and the title ...

(later Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

, who retired as 1st Viscount Hampden

Viscount Hampden is a title that has been created twice, once in the Peerage of Great Britain and once in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. The first creation came in the Peerage of Great Britain when the diplomat and politician Robert Hampde ...

). Before he was two, Thomas' father had died and he was raised thereafter by his mother, who sent him to Eton College

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

. There, he acted as President of the Eton Society

Eton College () is a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England. It was founded in 1440 by Henry VI under the name ''Kynge's College of Our Ladye of Eton besyde Windesore'',Nevill, p. 3 ff. intended as a sister institution to King's College, C ...

and was for three years a member of the school's cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balanced on three stumps. The batting side scores runs by striki ...

team, serving as captain of the playing eleven during his final year. He carried this enthusiasm for sport on to the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, where he was accepted to Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

after leaving Eton, and was drafted into the Cambridge playing eleven, playing for Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

and I Zingari

I Zingari (from dialectalized Italian , meaning "the Gypsies"; corresponding to standard Italian ') are English and Australian amateur cricket clubs, founded in 1845 and 1888 respectively. It is the oldest and perhaps the most famous of the 'wa ...

. His father had also played for Sussex. Upon his general admission from university, Freeman-Thomas then volunteered for fifteen years for the Sussex Artillery, achieving the rank of major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

.

Marriage and political career

In 1892, Freeman-Thomas assumed the additional surname of ''Freeman'' bydeed poll

A deed poll (plural: deeds poll) is a legal document binding on a single person or several persons acting jointly to express an intention or create an obligation. It is a deed, and not a contract because it binds only one party (law), party.

Et ...

and married the Hon. Marie Brassey, the daughter of Thomas Brassey

Thomas Brassey (7 November 18058 December 1870) was an English civil engineering contractor and manufacturer of building materials who was responsible for building much of the world's railways in the 19th century. By 1847, he had built about o ...

, then recently created Baron Brassey

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knigh ...

. Freeman-Thomas often cited her as a source of support, stating once: "My wife has been a constant inspiration and encouragement." The couple had two sons: Gerard, born 3 May 1893, and Inigo

Inigo derives from the Castilian rendering (Íñigo) of the medieval Basque name Eneko. Ultimately, the name means "my little (love)". While mostly seen among the Iberian diaspora, it also gained a limited popularity in the United Kingdom.

Ear ...

, born 25 July 1899. Gerard was killed in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

on 14 September 1914, and Inigo eventually succeeded his father as Marquess of Willingdon.

In 1897 Freeman-Thomas was appointed aide-de-camp to his father-in-law, who was then the Governor of Victoria

The governor of Victoria is the representative of the monarch, King Charles III, in the Australian state of Victoria. The governor is one of seven viceregal representatives in the country, analogous to the governors of the other states, and the ...

, Australia. Upon his return to the United Kingdom, Freeman-Thomas joined the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

and in 1900 was elected to the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

to represent the borough of Hastings

Hastings () is a large seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east to the county town of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west ...

. He then served as a junior lord of the Treasury

In the United Kingdom there are at least six Lords Commissioners of His Majesty's Treasury, serving as a commission for the ancient office of Treasurer of the Exchequer. The board consists of the First Lord of the Treasury, the Second Lord of the ...

in the Liberal Cabinet that sat from December 1905 to January 1906. Though he lost in the January 1906 elections, Freeman-Thomas returned to the House of Commons by winning the by-election for Bodmin, and, for some time, served as a secretary to the prime minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

, H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

. For his services in government, Freeman-Thomas was in 1910 elevated to the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted noble ranks.

Peerages include:

Australia

* Australian peers

Belgium

* Belgi ...

as Baron Willingdon of Ratton in the County of Sussex

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English C ...

, and the following year was appointed as Lord-in-waiting

Lords-in-waiting (male) or baronesses-in-waiting (female) are peers who hold office in the Royal Household of the sovereign of the United Kingdom. In the official Court Circular they are styled "Lord in Waiting" or "Baroness in Waiting" (without ...

to King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

, becoming a favourite tennis partner of the monarch. His father-in-law was created Earl Brassey at the coronation in that year.

Governorship of Bombay

Willingdon was on 17 February 1913 appointed as the Crown Governor of Bombay, replacing the Lord Sydenham of Combe, and to mark this event, Willingdon was on 12 March 1913 honoured with induction into the

Willingdon was on 17 February 1913 appointed as the Crown Governor of Bombay, replacing the Lord Sydenham of Combe, and to mark this event, Willingdon was on 12 March 1913 honoured with induction into the Order of the Indian Empire

The Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria on 1 January 1878. The Order includes members of three classes:

#Knight Grand Commander (GCIE)

#Knight Commander ( KCIE)

#Companion ( CIE)

No appoi ...

as a Knight Grand Commander (additional). Within a year, however, the First World War had erupted, and India, as a part of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, was immediately drawn into the conflict. Lord Willingdon strove to serve the Allied cause, taking responsibility for treating the wounded from the Mesopotamian campaign

The Mesopotamian campaign was a campaign in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I fought between the Allies represented by the British Empire, troops from Britain, Australia and the vast majority from British India, against the Central Powe ...

. In the midst of those dark times, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

returned to Bombay from South Africa and Willingdon was one of the first persons to welcome him and invite him to Government House

Government House is the name of many of the official residences of governors-general, governors and lieutenant-governors in the Commonwealth and the remaining colonies of the British Empire. The name is also used in some other countries.

Gover ...

for a formal meeting. This was the first meeting Willingdon had with Gandhi and he later described the Indian spiritual leader as "honest, but a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

and for that reason very dangerous."

In 1917, the year before Willingdon's resignation of the governorship, a severe famine broke out in the

In 1917, the year before Willingdon's resignation of the governorship, a severe famine broke out in the Kheda

Kheda, also known as Kaira, is a city and a municipality in the Indian state of Gujarat. It was former administrative capital of Kheda district. India's First Deputy Prime Minister Vallabhbhai Patel Was Born In Kheda District of Gujarat State.K ...

region of the Bombay Presidency

The Bombay Presidency or Bombay Province, also called Bombay and Sind (1843–1936), was an administrative subdivision (province) of British India, with its capital in the city that came up over the seven islands of Bombay. The first mainl ...

, which had far reaching effects on the economy and left farmers in no position to pay their taxes. Still, the government insisted that tax not only be paid but also implemented a 23% increase to the levies to take effect that year. Kheda thus became the setting for Gandhi's first ''satyagraha

Satyagraha ( sa, सत्याग्रह; ''satya'': "truth", ''āgraha'': "insistence" or "holding firmly to"), or "holding firmly to truth",' or "truth force", is a particular form of nonviolent resistance or civil resistance. Someone w ...

'' in India, and, with support from Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar, was an Indian lawyer, influential political leader, barrister and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of I ...

, Narhari Parikh

Narhari Dwarkadas Parikh was a writer, independence activist and social reformer from Gujarat, India. Influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, he was associated with Gandhian institutes throughout his life. He wrote biographies, edited works by associates ...

, Mohanlal Pandya, and Ravishankar Vyas

Ravishankar Vyas, better known as Ravishankar Maharaj, was an Indian independence activist, social worker and Gandhian from Gujarat.

Life

Ravishankar Vyas was born on 25 February 1884, Mahashivaratri, in Radhu village (now in Kheda district, ...

, organised a ''Gujarat sabha''. The people under Gandhi's influence then rallied together and sent a petition to Willingdon, asking that he cancel the taxes for that year. However, the Cabinet refused and advised the Governor to begin confiscating property by force, leading Gandhi to thereafter employ non-violent resistance to the government, which eventually succeeded and made Gandhi famous throughout India after Willingdon's departure from the colony. For his actions there, in relation to governance and the war effort, Willingdon was on 3 June 1918 appointed by the King as a Knight Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India

The Most Exalted Order of the Star of India is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria in 1861. The Order includes members of three classes:

# Knight Grand Commander (GCSI)

# Knight Commander ( KCSI)

# Companion ( CSI)

No appointments ...

.

Governorship of Madras

Willingdon returned to the United Kingdom from Bombay only briefly before he was appointed on 10 April 1919 as thegovernor of Madras

This is a list of the governors, agents, and presidents of colonial Madras, initially of the English East India Company, up to the end of British colonial rule in 1947.

English Agents

In 1639, the grant of Madras to the English was finalized be ...

. This posting came shortly after the Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms

The Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms or more briefly known as the Mont–Ford Reforms, were introduced by the colonial government to introduce self-governing institutions gradually in British India. The reforms take their name from Edwin Montagu, th ...

of 1918 were formalised by the Government of India Act, which distributed power in India between the executive and legislative bodies. Thus, in November 1920, Willingdon dropped the writs of election

A writ of election is a writ issued ordering the holding of an election. In Commonwealth countries writs are the usual mechanism by which general elections are called and are issued by the head of state or their representative. In the United S ...

for the first election for the Madras Legislative Council

Tamil Nadu Legislative Council was the upper house of the former bicameral legislature of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It began its existence as Madras Legislative Council, the first provincial legislature for Madras Presidency. It was initia ...

; however, due to their adherence to Gandhi's non-cooperation movement

The Non-cooperation movement was a political campaign launched on 4 September 1920, by Mahatma Gandhi to have Indians revoke their cooperation from the British government, with the aim of persuading them to grant self-governance.

, the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

party refused to run any candidates and the Justice Party was subsequently swept into power. Willingdon appointed A. Subbarayalu Reddiar

Diwan Bahadur Agaram Subbarayalu Reddiar (b. 15 October 1855 – d. November 1921) was a landlord and List of chief ministers of Madras Presidency, Chief Minister or Premier of Madras Presidency from 17 December 1920 to 11 July 1921.

Subbaraya ...

as his premier and Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn

Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn (Arthur William Patrick Albert; 1 May 185016 January 1942), was the seventh child and third son of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He served as Gov ...

(a former Governor General of Canada), opened the first meeting of the Legislative Assembly.

The following year, the Governor found himself dealing with a series of communal riots that in August 1921 broke out in the Malabar District

Malabar District, also known as Malayalam District, was an administrative district on the southwestern Malabar Coast of Bombay Presidency (1792-1800) and Madras Presidency (1800-1947) in British India, and independent India's Madras State (19 ...

. Following a number of cases of arson, looting, and assaults, Willingdon declared martial law just before the government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

sent in a large force to quell the riots. At around the same time, over 10,000 workers in the Buckingham and Carnatic Mills of Madras city organised for six months a general strike contemporaneous with the non-cooperation movement, which also sparked riots between pro- and anti-strike workers that were again only put down with police intervention.

When he returned once more to the United Kingdom at the end of his tenure as the Governor of Madras, Willingdon was made a viscount, becoming on 24 June 1924 the Viscount Willingdon, of Ratton in the County of Sussex.

Governor General of Canada

It was announced on 5 August 1926 that George V had, by commission under the

It was announced on 5 August 1926 that George V had, by commission under the royal sign-manual

The royal sign-manual is the signature of the sovereign, by the affixing of which the monarch expresses his or her pleasure either by order, commission, or warrant. A sign-manual warrant may be either an executive act (for example, an appointmen ...

and signet, approved the recommendation of his British prime minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As modern p ...

, Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

, to appoint Willingdon as his representative in Canada. The sitting Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

British Cabinet

The Cabinet of the United Kingdom is the senior decision-making body of His Majesty's Government. A committee of the Privy Council, it is chaired by the prime minister and its members include secretaries of state and other senior ministers.

...

had initially not considered Willingdon as a candidate for the governor generalcy, as he was seen to have less of the necessary knowledge of affairs and public appeal that other individuals held. However, the King himself put forward Willingdon's name for inclusion in the list sent to Canada, and it was that name that the then Canadian prime minister

The prime minister of Canada (french: premier ministre du Canada, link=no) is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the confidence of a majority the elected House of Commons; as such ...

, William Lyon Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King (December 17, 1874 – July 22, 1950) was a Canadian statesman and politician who served as the tenth prime minister of Canada for three non-consecutive terms from 1921 to 1926, 1926 to 1930, and 1935 to 1948. A Li ...

, chose as his preference for the nomination to the King. George V readily accepted, and Willingdon was notified of his appointment while on a diplomatic mission in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

.

This would be the last Canadian viceregal appointment made by the monarch in his or her capacity as sovereign of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

, as it was decided at the Imperial Conference in October 1926 that the Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

s of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

would thereafter be equal with one another, and the monarch would operate for a specific country only under the guidance of that country's ministers. Though this was not formalised until the enactment of the Statute of Westminster on 11 December 1931, the concept was brought into practice at the start of Willingdon's tenure as Governor General of Canada.

The

The Balfour Declaration of 1926

The Balfour Declaration of 1926, issued by the 1926 Imperial Conference of British Empire leaders in London, was named after Arthur Balfour, who was Lord President of the Council. It declared the United Kingdom and the Dominions to be:

The ...

, issued during the Imperial Conference, also declared that governors-general would cease to act as representatives of the British government in diplomatic relations between the United Kingdom and individual dominions. Accordingly, in 1928, the United Kingdom appointed its first High Commissioner to Canada thus effectively ending the governor general's, and Willingdon's, diplomatic role as the British government's envoy to Ottawa.''"What's in a name?" – The curious tale of the office of High Commissioner''by Lorna Lloyd. Willingdon arrived at

Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

in late 1926, and on 2 October was sworn in as governor general in a ceremony in the '' salon rouge'' of the parliament buildings of Quebec. His following journey to Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

to take up residence in the country's official royal and viceroyal home, Rideau Hall

Rideau Hall (officially Government House) is the official residence in Ottawa of both the Canadian monarch and their representative, the governor general of Canada. It stands in Canada's capital on a estate at 1 Sussex Drive, with the main b ...

, was just the first of many trips Willingdon took around Canada, meeting with a variety of Canadians and bringing with him what was described as "a sense of humour and an air of informality to his duties." He also became the first governor general to travel by air, flying from Ottawa to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

and back, as well as the first to make official visits abroad; not only did he tour the Caribbean

The Caribbean (, ) ( es, El Caribe; french: la Caraïbe; ht, Karayib; nl, De Caraïben) is a region of the Americas that consists of the Caribbean Sea, its islands (some surrounded by the Caribbean Sea and some bordering both the Caribbean Se ...

in 1929, but he further paid a visit to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, going there in 1927 to meet with and receive state honours from President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a History of the Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer ...

. On that visit, the Governor General was welcomed in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

by the King's emissary to the US, Vincent Massey

Charles Vincent Massey (February 20, 1887December 30, 1967) was a Canadian lawyer and diplomat who served as Governor General of Canada, the 18th since Confederation. Massey was the first governor general of Canada who was born in Canada after ...

, who would later himself be appointed as Governor General of Canada.

In Canada, Willingdon hosted members of the Royal Family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term ...

, including the King's two sons, Prince Edward, Prince of Wales, and Prince George, who, along with Baldwin, came to Canada to participate in the celebrations of the Diamond Jubilee

A diamond jubilee celebrates the 60th anniversary of a significant event related to a person (e.g. accession to the throne or wedding, among others) or the 60th anniversary of an institution's founding. The term is also used for 75th annivers ...

of Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

. The Princes resided at Rideau Hall and the Prince of Wales, accompanied by Willingdon, dedicated at the Peace Tower

The Peace Tower (french: link=no, Tour de la Paix) is a focal bell and clock tower sitting on the central axis of the Centre Block of the Canadian parliament buildings in Ottawa, Ontario. The present incarnation replaced the Victoria Tower af ...

both the altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paga ...

of the Memorial Chamber and the Dominion Carillon, the first playing of which on that day was heard by listeners across the country on the first ever coast-to-coast radio broadcast in Canada. This dedication marked the completion of the Centre Block

The Centre Block (french: Édifice du Centre) is the main building of the Canadian parliamentary complex on Parliament Hill, in Ottawa, Ontario, containing the House of Commons and Senate chambers, as well as the offices of a number of members ...

of Parliament Hill

Parliament Hill (french: Colline du Parlement, colloquially known as The Hill, is an area of Crown land on the southern banks of the Ottawa River in downtown Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Its Gothic revival suite of buildings, and their architectu ...

, and the following year, Willingdon moved the annual governor general's New Year

New Year is the time or day currently at which a new calendar year begins and the calendar's year count increments by one. Many cultures celebrate the event in some manner. In the Gregorian calendar, the most widely used calendar system to ...

's levée

A levee (), dike (American English), dyke (Commonwealth English), embankment, floodbank, or stop bank is a structure that is usually earthen and that often runs parallel to the course of a river in its floodplain or along low-lying coastlin ...

to that building from the East Block

The East Block (officially the Eastern Departmental Building; french: Édifice administratif de l'est) is one of the three buildings on Canada's Parliament Hill, in Ottawa, Ontario, containing offices for parliamentarians, as well as some preser ...

, where the party had been held since 1870. A few months before the end of his viceregal tenure in Canada, Willingdon was once more elevated in the peerage, becoming on 23 February 1931 the Earl of Willingdon and Viscount Ratendone.

In their time the viceroyal couple, the Earl and Countess of Willingdon fostered their appreciation of the arts, building on previous governor general the Earl Grey's Lord Grey Competition for Music and Drama by introducing the Willingdon Arts Competition, which dispensed awards for painting and sculpture. They also left at Rideau Hall a collection of carpets and ''objets d'art

In art history, the French term Objet d’art describes an ornamental work of art, and the term Objets d’art describes a range of works of art, usually small and three-dimensional, made of high-quality materials, and a finely-rendered finish th ...

'' that they had collected during their travels around India and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, and many of which were restored in 1993 to the Long Gallery

In architecture, a long gallery is a long, narrow room, often with a high ceiling. In Britain, long galleries were popular in Elizabethan and Jacobean houses. They were normally placed on the highest reception floor of English country hous ...

of Rideau Hall. However, Willingdon's tastes also included sports, particularly fishing, tennis, skating, skiing, curling, cricket, and golf. For the latter, he in 1927 donated to the Royal Canadian Golf Association

The Royal Canadian Golf Association (RCGA), branded as Golf Canada, is the sports governing body, governing body of golf in Canada.

Beginnings

Golf Canada was founded on June 6, 1895, as the ''Canadian Golf Association'' at the Royal Ottawa Golf ...

the Willingdon Cup

The Willingdon Cup is an annual amateur golf team competition among Canada's provinces.

History

The Governor General of Canada, Lord Willingdon, donated the cup to Golf Canada (then known as the Royal Canadian Golf Association) in 1927, for annu ...

for Canadian interprovincial amateur golf competition, which has been contested annually since that year.

During his residence in Ottawa, Willingdon was a regular attendee at home matches of the Ottawa Senators

The Ottawa Senators (french: Sénateurs d'Ottawa), officially the Ottawa Senators Hockey Club and colloquially known as the Sens, are a professional ice hockey team based in Ottawa. They compete in the National Hockey League (NHL) as a membe ...

, continuing a tradition of patronage by sitting Governors-General of the local professional club. In 1930, he donated a trophy to be awarded to the Senators player "of the greatest assistance to his team", which the organization cheekily interpreted as an award for the player to lead the team in assists and dubbed the Willington Trophy.

Viceroy and Governor-General of India

He had not been Governor General of Canada for five years before Willingdon received word that he was to be sent back to India as that country's viceroy and governor general. After being appointed to the

He had not been Governor General of Canada for five years before Willingdon received word that he was to be sent back to India as that country's viceroy and governor general. After being appointed to the British Privy Council

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of ei ...

on 20 March 1931, he was sworn in as such on 18 April 1931, merely two weeks after he was replaced in Canada by the Earl of Bessborough. When Willingdon arrived again in India, the country was gripped by the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

and was soon leading Britain's departure from the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

, seeing thousands of tonnes of gold shipped to the United Kingdom through the port of Bombay. Of this, Willingdon said: "For the first time in history, owing to the economic situation, Indians are disgorging gold. We have sent to London in the past two or three months, £25,000,000 sterling and I hope that the process will continue."

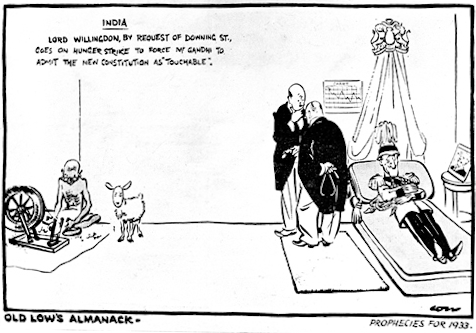

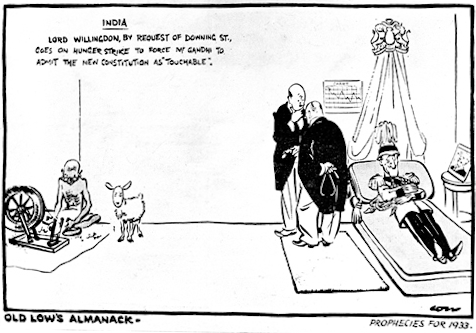

Jailing leaders of Congress

Simultaneously, Willingdon found himself dealing with the consequences of the nationalistic movements thatGandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

had earlier started when Willingdon was Governor of Bombay and then Madras. The India Office

The India Office was a British government department established in London in 1858 to oversee the administration, through a Viceroy and other officials, of the Provinces of India. These territories comprised most of the modern-day nations of I ...

told Willingdon that he should conciliate only those elements of Indian opinion that were willing to work with the Raj. That did not include Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

and the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

, which launched its Civil Disobedience Movement on 4 January 1932. Therefore, Willingdon took decisive action. He imprisoned Gandhi. He outlawed the Congress, he rounded up all members of the Working Committee and the Provincial Committees and imprisoned them, and banned Congress youth organizations. In total he imprisoned 80,000 Indian activists. Without most of their leaders, protests were uneven and disorganized, boycotts were ineffective, illegal youth organizations proliferated but were ineffective, more women became involved, and there was terrorism, especially in the North-West Frontier Province

The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP; ps, شمال لویدیځ سرحدي ولایت, ) was a Chief Commissioner's Province of British India, established on 9 November 1901 from the north-western districts of the Punjab Province. Followin ...

. Gandhi remained in prison until 1933. Willingdon relied on his military secretary, Hastings Ismay

Hastings Lionel Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay (21 June 1887 – 17 December 1965), was a diplomat and General (United Kingdom), general in the British Indian Army who was the first Secretary General of NATO. He also was Winston Churchill's chief mil ...

, for his personal safety.

Construction projects

It was also by Willingdon's hand, as Governor-in-Council, that the Lloyd Barrage was commissioned, seeing £20 million put into the construction of the barrage across the mouth of the

It was also by Willingdon's hand, as Governor-in-Council, that the Lloyd Barrage was commissioned, seeing £20 million put into the construction of the barrage across the mouth of the Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

, which not only provided labour but also brought millions of hectares of land in the Thar Desert

The Thar Desert, also known as the Great Indian Desert, is an arid region in the north-western part of the Indian subcontinent, Subcontinent that covers an area of and forms a natural boundary between India and Pakistan. It is the world's Li ...

under irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow Crop, crops, Landscape plant, landscape plants, and Lawn, lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,00 ...

. Further, Willingdon established the Willingdon Airfield

Safdarjung Airport is an airport in New Delhi, India, in the neighbourhood of the same name. Established during the British Raj as Willingdon Airfield, it started operations as an aerodrome in 1929, when it was India's second airport after the ...

(now known as Safdarjung Airport) in Delhi

Delhi, officially the National Capital Territory (NCT) of Delhi, is a city and a union territory of India containing New Delhi, the capital of India. Straddling the Yamuna river, primarily its western or right bank, Delhi shares borders w ...

and, after he was denied entry to the Royal Bombay Yacht Club

The Royal Bombay Yacht Club (RBYC) is one of the premier gentlemens' clubs which was founded in 1846 in Colaba (formerly Wellington Pier), an area of Mumbai in India. The building was designed by John Adams, who also designed the nearby Royal ...

because he was accompanied by Indian friends, despite his being the viceroy, Willingdon was motivated to establish the Willingdon Sports Club

The Royal Willingdon Sports Club is a private sports club in South Mumbai.

The club was founded in 1918 by Lord Willingdon, at that time Governor of Bombay. Amenities include an 18-hole golf course, six tennis courts, squash and badminton cour ...

in Bombay, with membership open to both Indians and British and which still operates today.

As he had been in Canada, Willingdon acted for India as Chief Scout A Chief Scout is the principal or head scout for an organization such as the military, colonial administration or expedition or a talent scout in performing, entertainment or creative arts, particularly sport. In sport, a Chief Scout can be the prin ...

of the Bharat Scouts and Guides

Bharat, or Bharath, may refer to:

* Bharat (term), the name for India in various Indian languages

** Bharata Khanda, the Sanskrit name for the Indian subcontinent (or South Asia)

* Bharata, the name of several legendary figures or groups:

** Bha ...

and took this role as more than an ''ex-officio'' title. Convinced that Scouting

Scouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth movement employing the Scout method, a program of informal education with an emphasis on practical outdoor activities, including camping, woodcraft, aquatics, hiking, backpacking ...

would contribute greatly to the welfare of India, he promoted the organisation, especially in rural villages, and requested that J. S. Wilson

Colonel John Skinner "Belge" Wilson (1888–1969) was a Scottish scouting luminary and friend and contemporary of Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell, General Baden-Powell, recruited by him to head the International Bureau, later to be ...

pay special attention to cooperation between Scouting and village development.

Post-viceregal life

Once back in the United Kingdom, Willingdon associated withRoland Gwynne

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Roland Vaughan Gwynne DSO, DL, JP (16 May 188215 November 1971) was a British soldier and politician who served as Mayor of Eastbourne, Sussex, from 1928 to 1931. He was also a patient, close friend, and probable lover o ...

. Along with Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

, Willingdon was one of the notable guests of parties at Gwynne's East Sussex

East Sussex is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England on the English Channel coast. It is bordered by Kent to the north and east, West Sussex to the west, and Surrey to the north-west. The largest settlement in East Su ...

estate, Folkington Manor

Folkington Manor (pronounced Fo'ington) is a grade II* listed country house situated in the village of Folkington two miles (3.2 km) west of Polegate, East Sussex, England.

History

Folkington Manor was built in 1843 by the architect W.J D ...

. He was also honoured by George V, not only by being appointed as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

The Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports is a ceremonial official in the United Kingdom. The post dates from at least the 12th century, when the title was Keeper of the Coast, but may be older. The Lord Warden was originally in charge of the Cinqu ...

—one of the higher honours bestowed by the sovereign and normally reserved for members of the Royal Family and former prime ministers—but he was also elevated once more in the peerage, being created Marquess of Willingdon by Edward VIII on 26 May 1936, making him the most recent person to be promoted to such a rank.

Willingdon did not cease diplomatic life altogether: he undertook a goodwill mission to South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

, representing the Ibero-American Institute, and chaired the British committee on the commissioning of army officers. In 1940, he also represented the United Kingdom at the celebrations for the centennial of the formation of New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. The next year, however, on 12 August, the Marquess of Willingdon died at 5 Lygon Place, near Ebury Street

Ebury Street () is a street in Belgravia, City of Westminster, London. It runs from a Grosvenor Gardens junction south-westwards to Pimlico Road. It was built mostly in the period 1815 to 1860.

Odd numbers 19 to 231 are on the south-east side; ...

, in London, and his ashes were interred in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

Honours

Titles

Knight Grand Commander of the Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire

The Most Eminent Order of the Indian Empire is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria on 1 January 1878. The Order includes members of three classes:

#Knight Grand Commander (:Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire, ...

(GCIE)

* 3 June 1918 – 21 July 1941: Knight Grand Commander of the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India

The Most Exalted Order of the Star of India is an order of chivalry founded by Queen Victoria in 1861. The Order includes members of three classes:

# Knight Grand Commander (GCSI)

# Knight Commander ( KCSI)

# Companion ( CSI)

No appointments ...

(GCSI)

* 20 July 1926 – 21 July 1941: Knight Grand Cross of the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honou ...

(GCMG)

* 5 August 1926 – 4 April 1931: Chief Scout for Canada

* 5 August 1926 – 4 April 1931: Honorary Member of the Royal Military College of Canada Club

* 20 March 1931 – 21 July 1941: Member of His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council (PC)

* 4 December 1917 – 21 July 1941: Knight Grand Cross of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

(GBE)

;Medals

* 1902: King Edward VII Coronation Medal

The King Edward VII Coronation Medal was a commemorative medal issued in 1902 to celebrate the coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra.

Issue

The medal was awarded in silver and bronze. It was issued in silver to members of the Royal fa ...

* 1911: King George V Coronation Medal

The King George V Coronation Medal was a commemorative medal instituted in 1911 to celebrate the coronation of King George V, that took place on 22 June 1911.

Award

It was the first British Royal commemorative medal to be awarded to people who w ...

* 1935: King George V Silver Jubilee Medal

The King George V Silver Jubilee Medal is a commemorative medal, instituted to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the accession of King George V.

Issue

This medal was awarded as a personal souvenir by King George V to commemorate his Silver J ...

* 1937: King George VI Coronation Medal

The King George VI Coronation Medal was a commemorative medal, instituted to celebrate the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

Issue

This medal was awarded as a personal souvenir of King George VI's coronation. It was awarded to th ...

Honorary military appointments

* 5 August 1926 – 4 April 1931: Colonel ofthe Governor General's Horse Guards

The Governor General's Horse Guards is an armoured reconnaissance regiment in the Primary Reserve of the Canadian Army. The regiment is part of 4th Canadian Division's 32 Canadian Brigade Group and is based in Toronto, Ontario. It is the most se ...

* 5 August 1926 – 4 April 1931: Colonel of the Governor General's Foot Guards

The Governor General's Foot Guards (GGFG) is the senior reserve infantry regiment in the Canadian Army. Located in Ottawa at the Cartier Square Drill Hall, the regiment is a Primary Reserve infantry unit, and the members are part-time soldiers.

...

* 5 August 1926 – 4 April 1931: Colonel of the Canadian Grenadier Guards

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

* 1936 – 21 July 1941: Colonel of the 5th battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment

The Royal Sussex Regiment was a line infantry regiment of the British Army that was in existence from 1881 to 1966. The regiment was formed in 1881 as part of the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 35th (Royal Sussex) Regiment of Foot ...

Honorific eponyms

;Awards * : Willingdon Arts Competition * :Willingdon Cup

The Willingdon Cup is an annual amateur golf team competition among Canada's provinces.

History

The Governor General of Canada, Lord Willingdon, donated the cup to Golf Canada (then known as the Royal Canadian Golf Association) in 1927, for annu ...

;Organizations

* : Willingdon Club

The Royal Willingdon Sports Club is a private sports club in South Mumbai.

The club was founded in 1918 by Lord Willingdon, at that time Governor of Bombay. Amenities include an 18-hole golf course, six tennis courts, squash and badminton cour ...

, Mumbai

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

;Geographic locations

* : Mount Willingdon

Mount is often used as part of the name of specific mountains, e.g. Mount Everest.

Mount or Mounts may also refer to:

Places

* Mount, Cornwall, a village in Warleggan parish, England

* Mount, Perranzabuloe, a hamlet in Perranzabuloe parish, C ...

* : Willingdon

* : Willingdon Avenue, Burnaby

Burnaby is a city in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia, Canada. Located in the centre of the Burrard Peninsula, it neighbours the City of Vancouver to the west, the District of North Vancouver across the confluence of the Burrard I ...

* : Willingdon Heights

Willingdon Heights is a neighbourhood in Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. It is named after a major Burnaby thoroughfare Willingdon Avenue connecting North Burnaby with Kingsway (Vancouver), Kingsway and the Metrotown area in the south. Willingdo ...

, Burnaby

Burnaby is a city in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia, Canada. Located in the centre of the Burrard Peninsula, it neighbours the City of Vancouver to the west, the District of North Vancouver across the confluence of the Burrard I ...

* : Willingdon Dam, Junagadh

Junagadh () is the headquarters of Junagadh district in the Indian state of Gujarat. Located at the foot of the Girnar hills, southwest of Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar (the state capital), it is the seventh largest city in the state.

Literally t ...

* : Willingdon Airport, New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament House ...

(later renamed Safdarjung Airport)

* : IAF Willingdon, New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament House ...

* : Willingdon Island

Willingdon Island is the largest artificial island in India, which forms part of the city of Kochi, in the state of Kerala. Much of the present Willingdon Island was claimed from the Lake of Kochi, filling in dredged soil around a previously e ...

;Schools

* : Willingdon Secondary School, Burnaby

Burnaby is a city in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia, Canada. Located in the centre of the Burrard Peninsula, it neighbours the City of Vancouver to the west, the District of North Vancouver across the confluence of the Burrard I ...

* : Willingdon College

Willingdon College, Sangli, is a college named after the former Governor of Bombay, The 1st Baron Willingdon (who has later created The 1st Marquess of Willingdon). Lord Willingdon later served as Viceroy of India, from 1931 until 1936. The c ...

, Sangli

Sangli () is a city and the district headquarters of Sangli District in the state of Maharashtra, in western India. It is known as the Turmeric City of Maharashtra due to its production and trade of the spice. Sangli is situated on the banks o ...

* : Willingdon Elementary School, Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

Arms

See also

*List of alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

This is a list of notable alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge. Some of the alumni noted are connected to Trinity through honorary degrees; not all studied at the College.

Politicians

Prime Ministers

* Stanley Baldwin, Stanley Baldwin, 1st E ...

References

External links

*Website of the Governor General of Canada entry for Freeman Freeman-Thomas

The Canadian Encyclopedia entry for Freeman Freeman-Thomas

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Willingdon, Freeman Freeman-Thomas, 1st Marquess of Viceroys of India 1930s in British India Governors of Bombay 1866 births 1941 deaths Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge Governors General of Canada Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire Liberal Party (UK) Lords-in-Waiting Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports Freeman-Thomas, Freeman Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire Freeman-Thomas, Freeman Freeman-Thomas, Freeman UK MPs who were granted peerages Scouting and Guiding in India Freeman-Thomas, Freeman English cricketers Cambridge University cricketers Sussex cricketers Chief Scouts of Canada Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Marquesses of Willingdon Barons created by George V Viscounts created by George V Peers created by Edward VIII Burials at Westminster Abbey People educated at Eton College