London Charterhouse on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The London Charterhouse is a historic complex of buildings in Farringdon,

''A History of the County of Middlesex:'' Volume 1: ''Physique, Archaeology, Domesday, Ecclesiastical Organization, The Jews, Religious Houses, Education of Working Classes to 1870, Private Education from Sixteenth Century'' (1969), pp. 159–169. accessed: 10 April 2009 In English, a Carthusian monastery is called a "Charterhouse" (derived from the

For several years after the dissolution of the priory, members of the Bassano family of instrument makers were amongst the tenants of the former monks' cells, whilst Henry VIII stored hunting equipment in the church. In 1545, the entire site was bought by Sir Edward (later Lord) North (c. 1496–1564), who transformed the complex into a luxurious mansion house. North demolished the church and built the Great Hall and adjoining Great Chamber. In 1558, during North's occupancy,

For several years after the dissolution of the priory, members of the Bassano family of instrument makers were amongst the tenants of the former monks' cells, whilst Henry VIII stored hunting equipment in the church. In 1545, the entire site was bought by Sir Edward (later Lord) North (c. 1496–1564), who transformed the complex into a luxurious mansion house. North demolished the church and built the Great Hall and adjoining Great Chamber. In 1558, during North's occupancy,

File:Charterhouse, EC1 - geograph.org.uk - 27285.jpg, The Great Hall viewed from Master's Court

File:Charterhouse altar.jpg, Altar in the south aisle of the Chapel

File:Cloister - Charterhouse Square.jpg, The cloister

File:The Charterhouse gardens.jpg, View of the Charterhouse from the gardens

File:The Great Chamber at the Charterhouse.jpg, The newly refurbished Great Chamber

Barrett, Charles Raymond Booth. ''Charterhouse, 1611–1895: in pen and ink'' (1895; Internet Archive)

{{History of the formation of Islington Archaeological sites in London Carthusian monasteries in England Christian monasteries established in the 14th century Cultural and educational buildings in London Defunct hospitals in London Monasteries dissolved under the English Reformation Grade I listed almshouses Grade I listed buildings in the London Borough of Islington Grade I listed educational buildings Grade I listed monasteries History of the London Borough of Islington Monasteries in London Religiously motivated violence in England 1371 establishments in England 1537 disestablishments in England Smithfield, London

London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

, dating back to the 14th century. It occupies land to the north of Charterhouse Square

Charterhouse Square is a garden square, a pentagonal space, in Farringdon, in the London Borough of Islington, and close to the former Smithfield Meat Market. The square is the largest courtyard or yard associated with the London Charterhouse, m ...

, and lies within the London Borough of Islington

The London Borough of Islington ( ) is a London borough in Inner London. Whilst the majority of the district is located in north London, the borough also includes a significant area to the south which forms part of central London. Islington has ...

. It was originally built (and takes its name from) a Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has its ...

priory, founded in 1371 on the site of a Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

burial ground. Following the priory's dissolution

Dissolution may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Books

* ''Dissolution'' (''Forgotten Realms'' novel), a 2002 fantasy novel by Richard Lee Byers

* ''Dissolution'' (Sansom novel), a 2003 historical novel by C. J. Sansom Music

* Dissolution, in mu ...

in 1537, it was rebuilt from 1545 onwards to become one of the great courtyard house

A courtyard house is a type of house—often a large house—where the main part of the building is disposed around a central courtyard. Many houses that have courtyards are not courtyard houses of the type covered by this article. For example, la ...

s of Tudor London. In 1611, the property was bought by Thomas Sutton

Thomas Sutton (1532 – 12 December 1611) was an English civil servant and businessman, born in Knaith, Lincolnshire. He is remembered as the founder of the London Charterhouse and of Charterhouse School.

Life

Sutton was the son of an official ...

, a businessman and "the wealthiest commoner in England", who established a school for the young and an almshouse

An almshouse (also known as a bede-house, poorhouse, or hospital) was charitable housing provided to people in a particular community, especially during the medieval era. They were often targeted at the poor of a locality, at those from certain ...

for the old. The almshouse remains in occupation today, while the school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes compuls ...

was re-located in 1872 to Godalming

Godalming is a market town and civil parish in southwest Surrey, England, around southwest of central London. It is in the Borough of Waverley, at the confluence of the Rivers Wey and Ock. The civil parish covers and includes the settleme ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

.

Although substantial fragments survive from the monastic period, most of the standing buildings date from the Tudor era. Thus, today the complex "conveys a vivid impression of the type of large rambling 16th-century mansion that once existed all round London".

History

Priory

In 1348,Walter Manny

Walter Manny (or Mauny), 1st Baron Manny, Order of the Garter, KG (c. 1310 – 14 or 15 January 1372), mercenary, soldier of fortune and founder of the London Charterhouse, Charterhouse, was from Masny in County of Hainaut, Hainault, from whose ...

rented of land in Spital Croft, north of Long Lane, from the Master and Brethren of St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (died ...

for a graveyard and plague pit for victims of the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

. A chapel and hermitage were constructed, renamed New Church Haw; but in 1371 this land was granted for the foundation of a Carthusian

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has its ...

monastery under the name of "The House of the Salutation of the Mother of God"''Religious Houses: House of Carthusian monks''''A History of the County of Middlesex:'' Volume 1: ''Physique, Archaeology, Domesday, Ecclesiastical Organization, The Jews, Religious Houses, Education of Working Classes to 1870, Private Education from Sixteenth Century'' (1969), pp. 159–169. accessed: 10 April 2009 In English, a Carthusian monastery is called a "Charterhouse" (derived from the

Grande Chartreuse

Grande Chartreuse () is the head monastery of the Carthusian religious order. It is located in the Chartreuse Mountains, north of the city of Grenoble, in the commune of Saint-Pierre-de-Chartreuse (Isère), France.

History

Originally, the ch ...

, the original monastery of the order), and thus the Carthusian monastery in London was referred to as the "London Charterhouse." As per Carthusian custom, the twenty-five monks each had their own small building and garden. Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

came to the monastery for spiritual recuperation.

The monastery was closed in 1537, in the Dissolution of the Monasteries during the English Reformation

The English Reformation took place in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away from the authority of the pope and the Catholic Church. These events were part of the wider European Protestant Reformation, a religious and poli ...

. As they resisted Henry VIII's claim to be Head of the Church, the members of the community were treated harshly: the Prior

Prior (or prioress) is an ecclesiastical title for a superior in some religious orders. The word is derived from the Latin for "earlier" or "first". Its earlier generic usage referred to any monastic superior. In abbeys, a prior would be l ...

, John Houghton was hanged, drawn and quartered

To be hanged, drawn and quartered became a statutory penalty for men convicted of high treason in the Kingdom of England from 1352 under Edward III of England, King Edward III (1327–1377), although similar rituals are recorded during the rei ...

at Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and south (modern Ox ...

and ten monks were taken to the nearby Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

; nine of these men were starved to death and the tenth was executed three years later at Tower Hill

Tower Hill is the area surrounding the Tower of London in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is infamous for the public execution of high status prisoners from the late 14th to the mid 18th century. The execution site on the higher grou ...

. They constitute the group known as the Carthusian Martyrs of London

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians ( la, Ordo Cartusiensis), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has it ...

.

Tudor mansion

For several years after the dissolution of the priory, members of the Bassano family of instrument makers were amongst the tenants of the former monks' cells, whilst Henry VIII stored hunting equipment in the church. In 1545, the entire site was bought by Sir Edward (later Lord) North (c. 1496–1564), who transformed the complex into a luxurious mansion house. North demolished the church and built the Great Hall and adjoining Great Chamber. In 1558, during North's occupancy,

For several years after the dissolution of the priory, members of the Bassano family of instrument makers were amongst the tenants of the former monks' cells, whilst Henry VIII stored hunting equipment in the church. In 1545, the entire site was bought by Sir Edward (later Lord) North (c. 1496–1564), who transformed the complex into a luxurious mansion house. North demolished the church and built the Great Hall and adjoining Great Chamber. In 1558, during North's occupancy, Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

used the house during the preparations for her coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a coronation crown, crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the ...

.

Following North's death, the property was purchased by Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, (Kenninghall, Norfolk, 10 March 1536Tower Hill, London, 2 June 1572) was an English nobleman and politician. Although from a family with strong Roman Catholic leanings, he was raised a Protestant. He was a ...

, who renamed it Howard House. In 1570, following his imprisonment in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

for scheming to marry Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legitimate child of James V of Scot ...

, Norfolk was placed under house arrest at the Charterhouse. He occupied his time by embellishing the house, and built a long terrace in the garden (which survives as the "Norfolk Cloister") leading to a tennis court. In 1571, Norfolk's involvement in the Ridolfi plot

The Ridolfi plot was a Roman Catholic plot in 1571 to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I of England and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots. The plot was hatched and planned by Roberto Ridolfi, an international banker who was able to travel betwee ...

was exposed after a ciphered letter from Mary was discovered under a doormat in the house; he was executed the following year.

The property passed to Norfolk's son, Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk

Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk, (24 August 156128 May 1626) of Audley End House in the parish of Saffron Walden in Essex, and of Suffolk House near Westminster, a member of the House of Howard, was the second son of Thomas Howard, 4th ...

. During his occupancy, James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

held court there on his first entrance into London in 1603.

Almshouse and school

In May 1611 it came into the hands ofThomas Sutton

Thomas Sutton (1532 – 12 December 1611) was an English civil servant and businessman, born in Knaith, Lincolnshire. He is remembered as the founder of the London Charterhouse and of Charterhouse School.

Life

Sutton was the son of an official ...

(1532–1611) of Knaith

Knaith is a village and civil parish about south of the town of Gainsborough in the West Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 335.

Knaith is a community with roots in Anglo-Saxon ...

, Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

. He was appointed Master of Ordnance in Northern Parts, and acquired a fortune by the discovery of coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

on two estates which he had leased near Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

, and later, upon moving to London, he carried on a commercial career. Before he died on 12 December of that year, he endowed a hospital on the site of the Charterhouse, calling it the Hospital of King James; and in his will he bequeathed money to maintain a chapel, hospital (almshouse

An almshouse (also known as a bede-house, poorhouse, or hospital) was charitable housing provided to people in a particular community, especially during the medieval era. They were often targeted at the poor of a locality, at those from certain ...

) and school.

In the ''Case of Sutton's Hospital

''Case of Sutton's Hospital'' (1612) 77 Eng Rep 960 is an old common law case decided by Sir Edward Coke. It concerned The Charterhouse, London which was held to be a properly constituted corporation.

Facts

Thomas Sutton was a coal mine owner a ...

'', his will was hotly contested but upheld in court, meaning the foundation was constituted to afford a home for eighty male pensioners ("gentlemen by descent and in poverty, soldiers that have borne arms by sea or land, merchants decayed by piracy or shipwreck, or servants in household to the King or Queens Majesty"), and to educate forty boys.

Charterhouse early established a reputation for excellence in hospital care and treatment, thanks in part to Henry Levett

Dr Henry Levett (c.1668 – 2 July 1725) was an English physician who wrote a pioneering tract on the treatment of smallpox and served as chief physician at the Charterhouse, London.

Early life

Henry Levett was born in about 1668, the son of W ...

, M.D., an Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

graduate who joined the school as physician in 1712. Levett was widely esteemed for his medical writings, including an early tract on the treatment of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

. He was buried in Charterhouse Chapel, and his widow married Andrew Tooke

Andrew Tooke (1673–1732) was an English scholar, headmaster of Charterhouse School, Gresham Professor of Geometry, Fellow of the Royal Society and translator of ''Tooke's Pantheon'', a standard textbook for a century on Greek mythology.

Life

H ...

, the master of Charterhouse.

The school, Charterhouse School, developed beyond the original intentions of its founder, to become a well-regarded public school

Public school may refer to:

* State school (known as a public school in many countries), a no-fee school, publicly funded and operated by the government

* Public school (United Kingdom), certain elite fee-charging independent schools in England an ...

. In 1872, under the headmastership of William Haig Brown

William Haig Brown (1823–1907) was an English cleric and reforming headmaster of Charterhouse School.

Life

Born at Bromley by Bow, Middlesex, on 3 December 1823, he was third son of Thomas Brown of Edinburgh and his wife Amelia, daughter of Jo ...

, the school moved to new buildings in the parish of Godalming

Godalming is a market town and civil parish in southwest Surrey, England, around southwest of central London. It is in the Borough of Waverley, at the confluence of the Rivers Wey and Ock. The civil parish covers and includes the settleme ...

in Surrey, opening on 18 June.

Twentieth century

Following the departure of Charterhouse School, its buildings, on the site of the former monastic great cloister, were taken over by Merchant Taylors' School, until that moved out in turn in 1933 to a new site near Northwood,Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

. The school buildings then became home to the St Bartholomew's Hospital

St Bartholomew's Hospital, commonly known as Barts, is a teaching hospital located in the City of London. It was founded in 1123 and is currently run by Barts Health NHS Trust.

History

Early history

Barts was founded in 1123 by Rahere (died ...

Medical School, and (though now much redeveloped) remain one of the sites occupied by its successor, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry

, mottoeng = Temper the bitter things in life with a smile

, parent = Queen Mary University of London

, president = Lord Mayor of London

, head_label = Warden

, head = Mark Caulfield

, students = 3,410

, undergrad = 2,23 ...

. The main part of the cloister garth continues to be a well-tended site mostly laid to lawn in the quadrangle of the university site.

The principal historic buildings of the Charterhouse were severely damaged by enemy action on the night of 10–11 May 1941, during the Blitz

Blitz, German for "lightning", may refer to:

Military uses

*Blitzkrieg, blitz campaign, or blitz, a type of military campaign

*The Blitz, the German aerial campaign against Britain in the Second World War

*, an Imperial German Navy light cruiser b ...

. The great hall and great chamber were severely damaged, the great staircase totally destroyed and the four sides of the Master's Court burnt out. These were restored between 1950 and 1959 by the architectural firm of Seely & Paget

Seely & Paget was the architectural partnership of John Seely, 2nd Baron Mottistone (1899–1963) and Paul Edward Paget (1901–1985).

Their work included the construction of Eltham Palace in the Art Deco style, and the post-World War II restora ...

, a rebuilding which allowed the exposure and embellishment of some medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the Post-classical, post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with t ...

and much 16th- and 17th-century fabric that had previously been concealed or obscured.

In preparation for and in conjunction with the restoration project, archaeological investigations were carried out by W. F. Grimes, which led to a greatly enhanced understanding of the layout of the monastic buildings, and the discovery of the remains of Walter de Manny, the founder, buried in a lead coffin before the high altar of the monastic chapel. These remains were identified as Manny's beyond reasonable doubt by the presence in the coffin of a lead ''bulla

Bulla (Latin, 'bubble') may refer to:

Science and medicine

* Bulla (dermatology), a bulla

* Bulla, a focal lung pneumatosis, an air pocket in the lung

* Auditory bulla, a hollow bony structure on the skull enclosing the ear

* Ethmoid bulla, pa ...

'' (seal) of Pope Clement VI

Pope Clement VI ( la, Clemens VI; 1291 – 6 December 1352), born Pierre Roger, was head of the Catholic Church from 7 May 1342 to his death in December 1352. He was the fourth Avignon pope. Clement reigned during the first visitation of the Bla ...

: in 1351 Clement had granted Manny a licence to select his own deathbed confessor

Confessor is a title used within Christianity in several ways.

Confessor of the Faith

Its oldest use is to indicate a saint who has suffered persecution and torture for the faith but not to the point of death.Museum of London

The Museum of London is a museum in London, covering the history of the UK's capital city from prehistoric to modern times. It was formed in 1976 by amalgamating collections previously held by the City Corporation at the Guildhall, London, Gui ...

the Charterhouse has opened up the site to the public. There are three key elements to the project: a new museum, which tells the story of the Charterhouse from the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

to the present day; a Learning Room and Learning Programme so that school groups can discover how the Charterhouse has been home to everyone from monks and monarchs to schoolboys and Brothers; and a newly landscaped Charterhouse Square open to the public so that more people can enjoy the green surroundings. Works for this project were completed and opened to the public in January 2017.

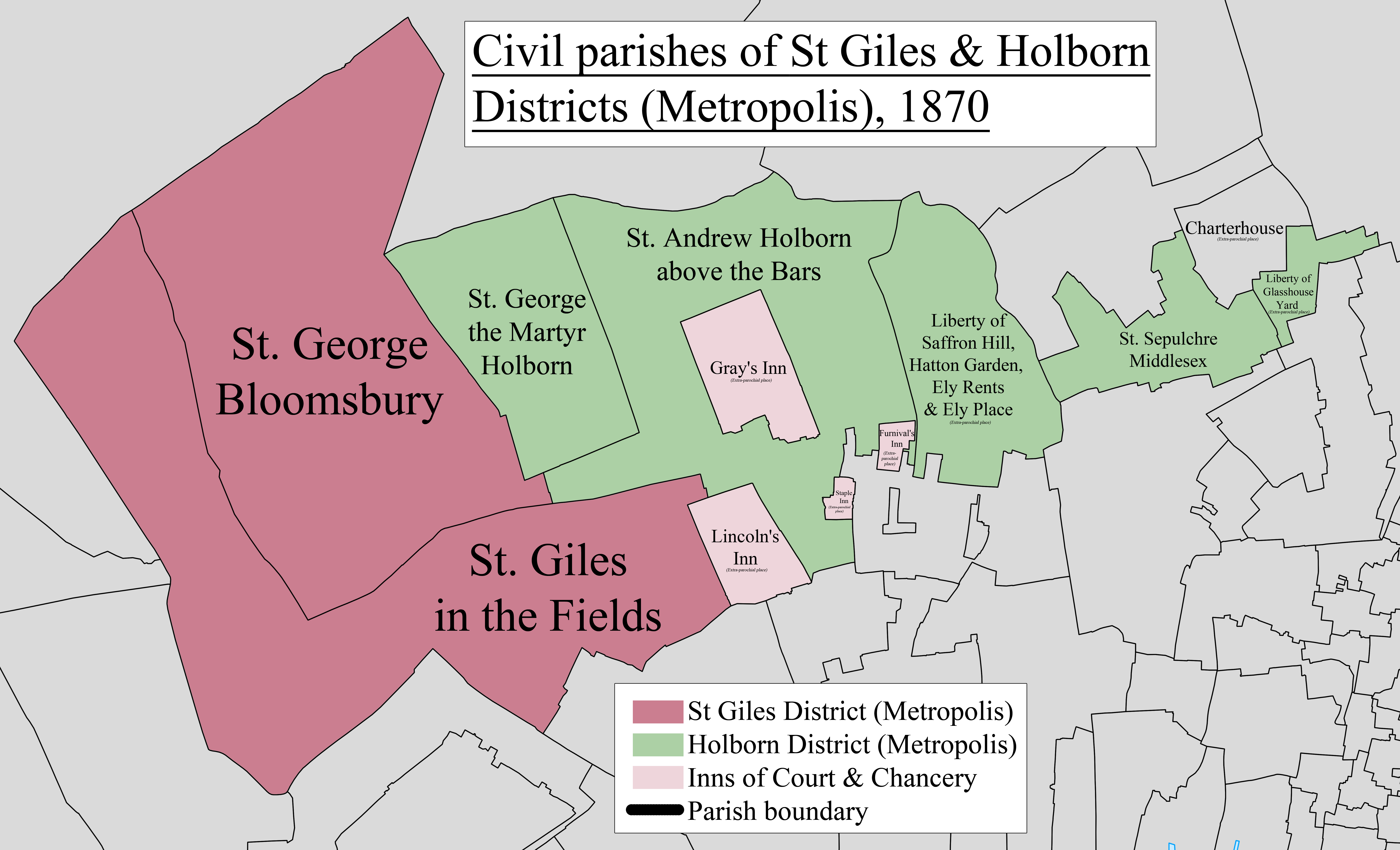

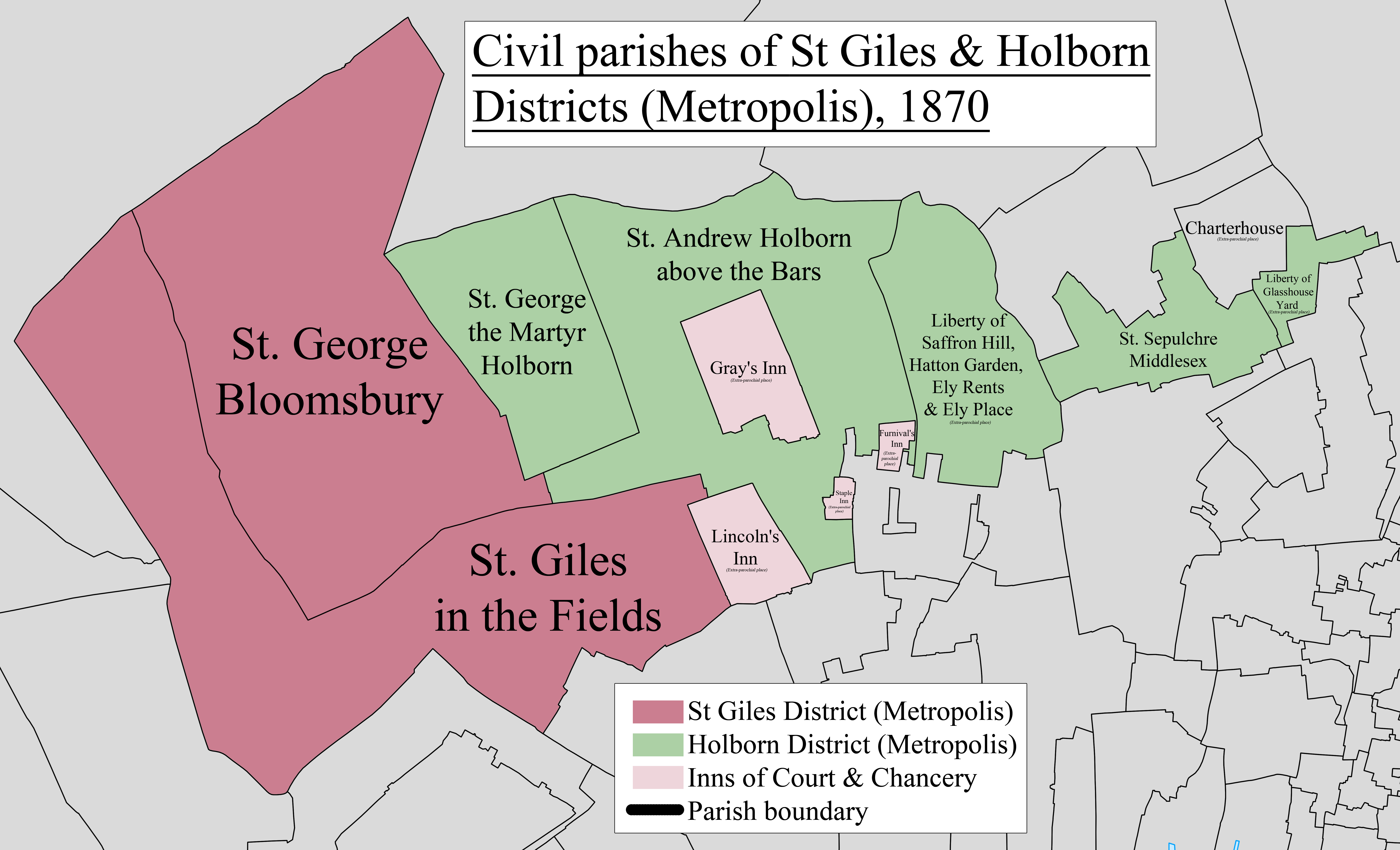

Local government

Charterhouse was anextra-parochial area

In England and Wales, an extra-parochial area, extra-parochial place or extra-parochial district was a geographically defined area considered to be outside any ecclesiastical or civil parish. Anomalies in the parochial system meant they had no ch ...

, an area lying outside any of the ancient parish units from which London's modern administrative units evolved through a succession of mergers. It was not included in one of the ''Districts'' - groupings of civil parishes, brought together for certain infrastructure purposes - under the Metropolis Management Act 1855

The Metropolis Management Act 1855 (18 & 19 Vict. c.120) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that created the Metropolitan Board of Works, a London-wide body to co-ordinate the construction of the city's infrastructure. The Act al ...

. In 1858, following the Extra-Parochial Places Act 1857, it effectively became a civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government below districts and counties, or their combined form, the unitary authority ...

for all purposes, with the provision that it would not form part of any poor law union, but later became a component of the ''Holborn Poor Law Union'' from 1877 until 1900.

In 1900 it became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury

The Metropolitan Borough of Finsbury was a Metropolitan borough within the County of London from 1900 to 1965, when it was amalgamated with the Metropolitan Borough of Islington to form the London Borough of Islington.

Formation and boundaries

...

, and was abolished as a separate civil parish in 1915. Since 1965 it has been part of the London Borough of Islington

The London Borough of Islington ( ) is a London borough in Inner London. Whilst the majority of the district is located in north London, the borough also includes a significant area to the south which forms part of central London. Islington has ...

in Greater London.

Nearby stations

The nearest tube station isBarbican

A barbican (from fro, barbacane) is a fortified outpost or fortified gateway, such as at an outer fortifications, defense perimeter of a city or castle, or any tower situated over a gate or bridge which was used for defensive purposes.

Europe ...

but Farringdon tube and surface rail station is also close.

Masters of Charterhouse

List of Masters of Charterhouse since 1611. style="font-size:100%;" * 1611–14: John Hutton, M.A. * 1614–15: Andrew Perne, M.A. * 1615–17: Peter Hooker, B.D. * 1617–24: Francis Beaumont, appointed by the King * 1624–37: Sir Robert Dallington, M.A. * 1637–50: George Garrard, M.A. * 1650–60: Edward Cressett * 1660–71: Sir Ralph Sydenham * 1671–7: Martin Clifford * 1677–85: William Erskine * 1685–1715:Thomas Burnet

Thomas Burnet (c. 1635? – 27 September 1715) was an English theologian and writer on cosmogony.

Life

He was born at Croft near Darlington in 1635. After studying at Northallerton Grammar School under Thomas Smelt, he went to Clare Colle ...

, M.A.

* 1715–37: John King, D.D.

* 1737–53: Nicholas Mann

* 1753–61: Philip Bearcroft, D.D.

* 1761–78: Samuel Salter, D.D.

* 1778–1804: William Ramsden, D.D.

* 1804–42: Philip Fisher, D.D.

* 1842–70: William Hale Hale

William Hale Hale (12 September 1795 – 27 November 1870) was an English churchman and author, Archdeacon of London in the Church of England, and Master of Charterhouse.

Life

He was son of John Hale, a surgeon, of Lynn, Norfolk; his father di ...

, M.A.

* 1872–85: George Currey, D.D.

* 1885–97: Richard Elwyn, M.A.

* 1897–1907: William Haig Brown

William Haig Brown (1823–1907) was an English cleric and reforming headmaster of Charterhouse School.

Life

Born at Bromley by Bow, Middlesex, on 3 December 1823, he was third son of Thomas Brown of Edinburgh and his wife Amelia, daughter of Jo ...

, LL.D.

* 1907–08: George Edward Jelf

George Edward Jelf (1834–1908) was an English churchman and Master of Charterhouse.

Life

The eldest son of seven children of Richard William Jelf and Emmy, Countess of Schlippenbach, lady-in-waiting to Frederica, Duchess of Cumberland, he was ...

, D.D.

* 1908–27: Gerald Stanley Davies, M.A.

* 1927–1935: William Thomas Baring Hayter

* 1935–1954: Edward StG. Schomberg

* 1954–61: John McLeod Campbell

John McLeod Campbell (4 May 1800 – 27 February 1872) was a Scottish minister and Reformed theologian. In the opinion of one German church historian, contemporaneous with Campbell, his theology was a highpoint of British theology during the ni ...

* 1962–73: Thomas Nevill

Sir Thomas Neville or Nevill (by 1484 – 29 May 1542) was a younger son of George Neville, 4th Baron Bergavenny. He was a prominent lawyer and a trusted councillor of King Henry VIII, and was elected Speaker of the House of Commons in 1515.

...

* 1973–84: Oliver van Oss

* 1984–96: Eric Harrison

* 1996–2001: Professor James Malpas

* 2001–2012: Dr James Thomson

* 2012–2017: Brigadier Charlie Hobson OBE (RM)

* 2017–2022: Ann Kenrick OBE

* 2022–present: Peter Aiers

Gallery

See also

*List of Carthusian monasteries

This is a list of Carthusian monasteries, or charterhouses, containing both extant and dissolved Monastery, monasteries of the Carthusians (also known as the Order of Saint Bruno) for monks and nuns, arranged by location under their present count ...

* Forty Martyrs of England and Wales

* Carthusian Martyrs

The Carthusian martyrs are those members of the Carthusian monastic order who have been persecuted and killed because of their Christian faith and their adherence to the Catholic religion. As an enclosed order the Carthusians do not, on principl ...

References

Sources

* * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

* *Barrett, Charles Raymond Booth. ''Charterhouse, 1611–1895: in pen and ink'' (1895; Internet Archive)

{{History of the formation of Islington Archaeological sites in London Carthusian monasteries in England Christian monasteries established in the 14th century Cultural and educational buildings in London Defunct hospitals in London Monasteries dissolved under the English Reformation Grade I listed almshouses Grade I listed buildings in the London Borough of Islington Grade I listed educational buildings Grade I listed monasteries History of the London Borough of Islington Monasteries in London Religiously motivated violence in England 1371 establishments in England 1537 disestablishments in England Smithfield, London