Antiquity

A scroll written by the Hebrew prophet Jeremiah (burnt by King Jehoiakim)

About 600 BC, Jeremiah of Anathoth wrote that the King of Babylon would destroy the land of Judah. As recounted inProtagoras' "On the Gods" (by Athenian authorities)

The Classical Greek philosopherDemocritus' writings (by Plato)

The philosopherChinese philosophy books (by Emperor Qin Shi Huang and anti-Qin rebels)

During the

During the Books of pretended prophecies (by Roman authorities)

In 186 BC, in an effort to suppress theJewish holy books (by the Seleucid monarch Antiochus IV)

In 168 BC theRoman history book (by the aediles)

In 25 AD SenatorGreek and Latin prophetic verse (by the emperor Augustus)

Suetonius tells us that, at the death of Marcus Lepidus (about 13 BC), Augustus assumed the office of Chief Priest, and burned over two thousand copies of Greek and Latin prophetic verse then current, the work of anonymous or unrespected authors (preserving the Sibylline Books).Torah scroll (by a Roman soldier)

Sorcery scrolls (by early converts to Christianity at Ephesus)

About the year 55 according to theRabbi Haninah ben Teradion burned with a Torah scroll (under Hadrian)

Under the emperor''

Burning of the Torah by Apostomus (precise time and circumstances debated)

Among five catastrophes said to have overtaken the Jews on theEpicurus' book (in Paphlagonia)

The book ''Established beliefs'' ofManichaean and Christian scriptures (by Diocletian)

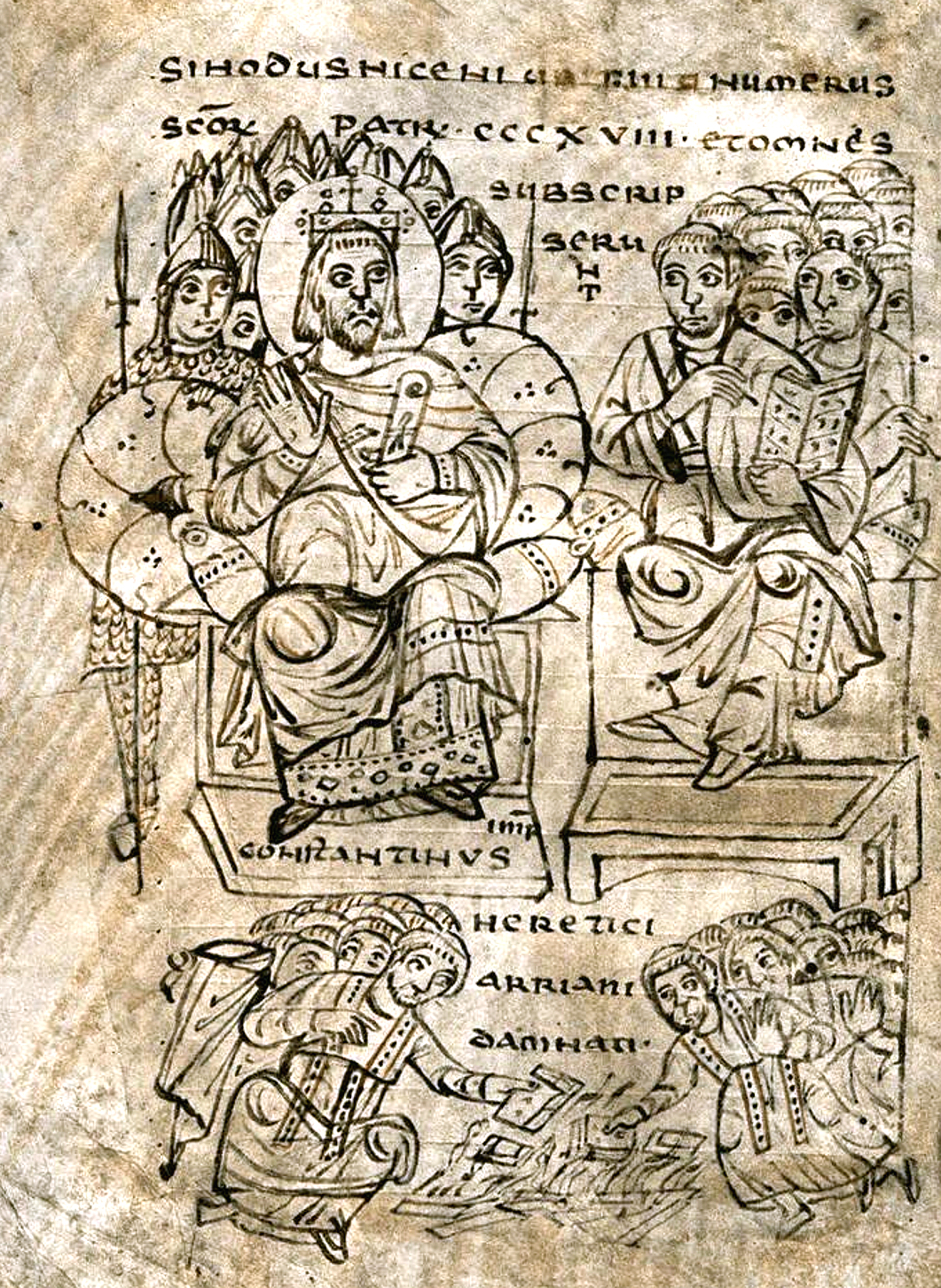

TheBooks of Arianism (after Council of Nicaea)

The books of

The books of Library of Antioch (by Jovian)

In 364, the Roman Catholic Emperor Jovian ordered the entire"Unacceptable writings" (by Athanasius)

The Sibylline books (various times)

TheWritings of Priscillian (by Roman authorities)

In 385, the theologianEtrusca Disciplina (by Roman authorities)

''Etrusca Disciplina'', theBooks on astrology (by Roman authorities)

In 409, the emperors Theodosius II and Honorius ordered that astrologers burn their books on pain of expulsion.Nestorius' books (by Theodosius II)

The books ofMiddle Ages

"Book of the Miracles of Creation" (reportedly destroyed by Saint Brendan)

According to the Dutch '' De Reis van Sinte Brandaen'' (Mediaeval Dutch for ''The Voyage of Saint Brendan''), one of the earliest accounts of the life of/ref>

Patriarch Eutychius' book (by Emperor Tiberius II Constantine)

Repeated destruction of Alexandria libraries (multiple people)

The library of theIconoclast writings (by Byzantine authorities)

Following the "Qur'anic texts with varying wording (ordered by the 3rd Caliph, Uthman)

Uthman ibn 'Affan, the thirdCompeting prayer books (at Toledo)

After the conquest ofby

Abelard forced to burn his own book (at Soissons)

The provincialThe writings of Arnold of Brescia (in France and Rome)

The rebellious monkNalanda University (by Muslims)

The library ofSamanid dynasty library (by Turks)

The Royal Library of theBuddhist writings in the Maldives (by royal dynasty converted to Islam)

Following the conversion of theBuddhist writings in the Gangetic plains region of India (by Turk-Mongol raiders)

According to William Johnston, as part of theAlamut Castle (by Mongols)

The famous library of theIsmaili Shite writings at Al-Azhar (by Saladin)

Between 120,000 and 2,000,000 were destroyed underDestruction of Cathar texts (Languedoc region of France, by the Catholic Church)

During the 13th century, the Catholic Church waged a brutal campaign against the

During the 13th century, the Catholic Church waged a brutal campaign against the Maimonides' philosophy (at Montpellier)

The Talmud (at Paris), first of many such burnings over the next centuries (by Royal and Church authorities)

In 1242, The French crown burned all copies of theRabbi Nachmanides' account of the Disputation of Barcelona (by Dominicans)

In 1263 theThe House of Wisdom library (at Baghdad)

TheLollard books and writings (by English law)

TheWycliffe's books (at Prague)

On 20 December 1409, PopeVillena's books (in Castile)

Codices of the peoples conquered by the Aztecs (by Itzcoatl)

According to the Madrid Codex, the fourthGemistus Plethon's ''Nómoi'' (by Patriarch Gennadius II)

After the death of the prominent late Byzantine scholarEarly Modern Period (from 1492 to 1650)

Decameron, Ovid and other "lewd" books (by Savonarola)

In 1497, followers of the Italian priestArabic and Hebrew books (in Andalucía)

In 1490 a number of Hebrew Bibles and other Jewish books were burned at the behest of the Spanish Inquisition. In 1499 or early 1500 about 5000 Arabic manuscripts, including a school library—all that could be found in the city—were consumed by flames in a public square inArabic books and archives in Oran (by Spanish conquerors)

In 1509 Spanish forces commanded by CountCatholic theological works (by Martin Luther)

At the instruction of ReformerLutheran and other Protestant writings (in the Habsburg Netherlands)

In March 1521 EmperorThe works of Galen and Avicenna (by Paracelsus)

In 1527, the innovative physician Paracelsus was licensed to practice in Basel, with the privilege of lecturing at the University of Basel. He published harsh criticism of the Basel physicians and apothecaries, creating political turmoil to the point of his life being threatened. He was prone to many outbursts of abusive language, abhorred untested theory, and ridiculed anybody who placed more importance on traditional medical texts than on practice ('The patients are your textbook, the sickbed is your study. If disease put us to the test, all our splendor, title, ring, and name will be as much help as a horse's tail'). In a display of his contempt for conventional medicine, Paracelsus publicly burned editions of the works of Galen andBooks and papers of the Portuguese Order of Christ (By Fra António of Lisbon)

In 1523, Fra António (also known as Antonius of Lisbon) a Spanish-born Hieronymites, Jerome friar, was given the authority and responsibility to "reform" the Order of Christ (Portugal), Order of Christ in Portugal. His reform included the burning of part of the Order's papers and books, as well as instigating the burning of human beings - he ordered two autos-da-fés, the first and only ones ever held in the Order's headquarters in Tomar, with a total of four peopleServetus' writings (burned with their author at Geneva, and also burned at Vienne)

In 1553, Servetus was burned as a heretic at the order of the city council of Geneva, dominated by John Calvin, Calvin – because a remark in his translation of Ptolemy's ''Geographia'' was considered an intolerable heresy. As he was placed on the stake, "around [Servetus'] waist were tied a large bundle of manuscript and a thick octavo printed book", his ''Christianismi Restitutio''. In the same year the Catholic authorities at Vienne also burned Servetus in effigy together with whatever of his writings fell into their hands, in token of the fact that Catholics and Protestants – mutually hostile in this time – were united in regarding Servetus as a heretic and seeking to extirpate his works. At the time it was considered that they succeeded, but three copies were later found to have survived, from which all later editions were printed.''The Historie of Italie'' (In England)

''The Historie of Italie'' (1549), a scholarly and in itself not particularly controversial book by William Thomas (scholar), William Thomas, was in 1554 "suppressed and publicly burnt" by order of Queen Mary I of England – after its author was executed on charges of treason. Enough copies survived for new editions to be published in 1561 and 1562, after Elizabeth I came to power.''Dictionary of National Biography'', volume LVI(1898), scanned volume from Internet Archive.

Religious and other writings of the Saint Thomas Christians (by the Portuguese Church in India)

On June 20, 1599 Aleixo de Menezes, Latin Church, Latin rite Archbishop of Goa, convened the Synod of Diamper at Udayamperoor (known as Diamper in non-vernacular sources). This diocesan synod or council was aimed at forcing the ancient Saint Thomas Christians of the Malabar Coast (modern Kerala state, India) to abandon their practices, customs and doctrines - the result of centuries of living their own Christian lives in an Indian environment - and force upon them instead the full doctrines and practices of 16th century European Catholic Christianity, at the time involved in a titanic struggle with the rising tide of European Protestantism. Among other things, the Synod of Diamper condemned as heretical numerous religious and other books current among the Saint Thomas Christians, which differed on numerous points from Catholic doctrine. All these were to be handed over to the Church, to be burned. Some of the books which are said to have been burnt at the Synod of Diamper are: 1.The book of the Infancy of the Saviour (History of Our Lord) 2. Book of John Braldon 3. The Pearl of Faith 4. The Book of the Fathers 5. The Life of the Abbot Isaias 6. The Book of Sunday 7. Maclamatas 8. Uguarda or the Rose 9. Comiz 10. The Epistle of Mernaceal 11. Menra 12. Of Orders 13. Homilies (in which the Eucharist is said to be the image of Christ) 14. Exposition of Gospels. 15. The Book of Rubban Hormisda 16. The Flowers of the Saints 17. The Book of Lots 18. The Parsimon or Persian Medicines. Dr Istvan Perczel, a Hungarian scholar researching Syrian Christians in India, found that certain texts survived the destruction of Syriac religious writings by the Portuguese missionaries. Manuscripts were either kept hidden by the Saint Thomas Christians or carried away by those of them who escaped from the area of Portuguese rule and sought refuge with Indian rulers. However, a systematic research is yet to be conducted, to determine which of the books listed as heretical at Diamper still exist and which are gone forever.Maya codices (by Spanish Bishop of Yucatan)

July 12, 1562, Fray Diego de Landa, acting Bishop of Yucatán – then recently conquered by the Spanish – threw into the fires the books of the Maya civilization, Maya. The number of destroyed books is greatly disputed. De Landa himself admitted to 27, other sources claim "99 times as many" – the later being disputed as an exaggeration motivated by anti-Spanish feeling, the so-called Black legend (Spain), Black Legend. Only three Maya codices and a fragment of a fourth survive. Approximately 5,000 Maya cult images were also burned at the same time. The burning of books and images alike were part of de Landa's effort to eradicate the Maya "idolatry, idol worship", which he considered "diabolical". As narrated by de Landa himself, he had gained access to the sacred books, transcribed on deerskin, by previously gaining the natives' trust and showing a considerable interest in their culture and language: "We found a large number of books in these characters and, as they contained nothing in which were not to be seen as superstition and lies of the devil, we burned them all, which they [the Maya] lamented to an amazing degree, and which caused them much affliction." De Landa was later recalled to Spain and accused of having acted illegally in Yucatán, though eventually found not guilty of these charges. Present-day apologists for de Landa assert that, while he had destroyed the Maya books, his own ''Relación de las cosas de Yucatán'' is a major source for the Mayan language and culture. Allen Wells calls his work an "ethnographic masterpiece", while William J. Folan, Laraine A. Fletcher and Ellen R. Kintz have written that Landa's account of Maya social organization and towns before conquest is a "gem."Arabic books in Spain (owners ordered to destroy their own books by King Philip II)

In 1567, Philip II of Spain issued a royal decree in Spain forbidding Moriscos (Muslims who had been converted to Christianity but remained living in distinct communities) from the Language death, use of Arabic on all occasions, formal and informal, speaking and writing. Using Arabic in any sense of the word would be regarded as a crime. They were given three years to learn a "Christian" language, after which they would have to get rid of all Arabic written material. It is unknown how many of the Moriscos complied with the decree and destroyed their own Arabic books and how many kept them in defiance of the King's decree; the decree is known to have triggered one of the largest Morisco Revolts"Obscene" Maltese poetry (by the Inquisition)

In 1584 Pasquale Vassallo, a Maltese people, Maltese Dominican Order, Dominican friar, wrote a collection of songs, of the kind known as "canczuni", in Italian and Maltese language, Maltese. The poems fell into the hands of other Dominican friars who denounced him for writing "obscene literature". At the order of the Inquisition in 1585 the poems were burned for this allegedly 'obscene' content.Arwi books (by Portuguese in India and Ceylon)

With the 16th-century extension of the Portuguese Empire to India and Ceylon, the staunchly Catholic colonizers were hostile to Muslims they found living there. An aspect of this was a Portuguese hostility to and destruction of writings in the Arwi language, a type of Tamil language, Tamil with many Arabic words, written in a variety of the Arabic script and used by local Muslims. Much of Arwi cultural heritage was thus destroyed, though the precise extent of the destruction might never be known.Luther's Bible translation (by German Catholics)

Uriel da Costa's book (by Jewish community and city authorities in Amsterdam)

The 1624 book ''An Examination of the Traditions of the Pharisees'', written by the dissident Jewish intellectual Uriel da Costa, was burned in public by joint action of the Amsterdam Jewish Community and the city's Protestant-dominated City Council. The book, which questioned the fundamental idea of the immortality#Religious, immortality of the soul, was considered heretical by the Jewish community, which excommunicated him, and was arrested by the Dutch authorities as a public enemy to religion.Marco Antonio de Dominis' writings (in Rome)

The theologian and scientist Marco Antonio de Dominis came in 1624 into conflict with the Inquisition in Rome and was declared "a relapsedEarly Modern Period (1650 to 1800)

Books burned by civil, military and ecclesiastical authorities between 1640 and 1660 (in Cromwell's England)

Sixty identified printed books, pamphlets and broadsheets and 3 newsbooks were ordered to be burned during this turbulent period, spanning the English Civil War and Oliver Cromwell's rule.Socinian and Anti-Trinitarian books (by secular and church authorities in the Dutch Republic)

As noted by Jonathan Israel, the Dutch Republic was more tolerant than other 17th century states, allowing a wide range of religious groups to practise more or less freely and openly disseminate their views. However, the dominant Calvinist Church drew the line at Socinian and Anti-Trinitarian doctrines which were deemed to "undermine the very foundations of Christianity". In the late 1640s and 1650s, Polish and German holders of such views arrived in the Netherlands as refugees from persecution in Poland and Brandenburg. Dutch authorities made an effort to stop them spreading their theological writings, by arrests and fines as well as book-burning. For example, in 1645, the burgomasters at Rotterdam discovered a stock of 100 books by Cellius and destroyed them. In 1659 Lancelot van Brederode published anonymously 900 copies of a 563-page book assailing the dominant Calvinist Church and the doctrine of the Trinity. The writer's identity was discovered and he was arrested and heavily fined, and the authorities made an effort to hunt down and destroy all copies of the book – but since it had already been distributed, many of the copies survived. The book ''Bescherming der Waerheyt Godts'' by Foeke Floris, a liberal Anabaptist preacher, was in 1687 banned by authorities in Friesland which deemed it to be Socinian, and all copies were ordered to be burned. In 1669 the Hof (high court) of Holland ordered the Amsterdam municipal authorities to raid booksellers in the city, seize and destroy Socinian books – especially the ''Biblioteca fratrum Polonorum'' ("Book of the Polish Brethren"), at the time known to be widely circulating in Amsterdam. The Amsterdam burgomasters felt obliged to go along with this, at least formally – but in fact some of them mitigated the practical effect by warning booksellers of impending raids.Book criticising Puritanism (in Boston)

The first book burning incident in the Thirteen Colonies occurred in Boston in 1651 when William Pynchon, founder of Springfield, Massachusetts, published ''The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption'', which criticised the Puritans, who were then in power in Massachusetts. The book became the first banned book in North America, and subsequently all known copies were publicly burned. Pynchon left for England prior to a scheduled appearance in court, and never returned.Manuscripts of John Amos Comenius (by anti-Swedish Polish partisans)

During the Northern Wars in 1655, the well-known Bohemian Protestant theologian and educator John Amos Comenius, then living in exile at the city of Leszno in Poland, declared his support for the Protestant Swedish side. In retaliation, Polish partisans burned his house, his manuscripts, and his school's printing press. Notably, the original manuscript of Comenius' ''Pansophiæ Prodromus'' was destroyed in the fire; fortunately, the text had already been printed and thus survived.Quaker books (in Boston)

In 1656 the authorities at Boston imprisoned the Religious Society of Friends, Quaker women preachers Ann Austin and Mary Fisher (missionary), Mary Fisher, who had arrived on a ship from Barbados. Among other things they were charged with "bringing with them and spreading here sundry books, wherein are contained most corrupt, heretical, and blasphemous doctrines contrary to the truth of the gospel here professed amongst us" as the colonial gazette put it. The books in question, about a hundred, were publicly burned in Boston's Market Square.Pascal's "Lettres provinciales" (by King Louis XIV)

As part of his intensive campaign against the Jansenists, King Louis XIV of France in 1660 ordered the book "Lettres provinciales" by Blaise Pascal – which contained a fierce defense of the Jansenist doctrines – to be shredded and burnt. Despite Louis XIV absolute power in France, this decree proved ineffective. "Lettres provinciales" continued to be clandestinely printed and disseminated, eventually outliving the Jansenist controversy which gave it birth and becoming recognized as a masterpiece of French prose.Hobbes books (at Oxford University)

In 1683 several books by Thomas Hobbes and other authors were burnt in Oxford University.Mythical (and/or mystical) writings of Moshe Chaim Luzzatto (by rabbis)

During the 1720s rabbis in Italy and Germany ordered the burning of the kabbalist writings of the then young Moshe Chaim Luzzatto. The Messianic prophecies, Messianic messages which Luzzatto claimed to have gotten from a being called "The Maggid" were considered heretical and potentially highly disruptive of the Jewish communities' daily life, and Luzzatto was ordered to cease disseminating them. Though Luzzatto in later life got considerable renown among Jews and his later books were highly esteemed, most of the early writings were considered irrevocably lost until some of them turned up in 1958 in a manuscript preserved in the Bodleian Library, Library of Oxford.Protestant books and Bibles (by Archbishop of Salzburg)

In 1731 Count Leopold Anton von Firmian – Archbishopric of Salzburg, Archbishop of Salzburg as well as its temporal ruler – embarked on a savage persecution of the Lutherans living in the rural regions of Salzburg. As well expelling tens of thousands of Protestant Salzburgers, the Archbishop ordered the wholesale seizure and burning of all Protestant books and Bibles.''Amalasunta'' (by Carlo Goldoni)

In 1733, Venetian playwright Carlo Goldoni burned his tragedy ''Amalasunta'' due to negative reception by his audiences.The writings of Johann Christian Edelmann (by Imperial authorities in Frankfurt)

In 1750, the Imperial Book Commission of the Holy Roman Empire at Frankfurt/Main ordered the wholesale burning of the works of Johann Christian Edelmann, a radical disciple of Spinoza who had outraged the Lutheran and Calvinist clergies by his Deism, his championing of sexual freedom and his asserting that Jesus had been a human being and not the Son of God. In addition, Edelmann was also an outspoken opponent of royal absolutism. With Frankfurt's entire magistracy and municipal government in attendance and seventy guards to hold back the crowds, nearly a thousand copies of Edelmann's writings were tossed on to a tower of flaming birch wood. Edelmann himself was granted refuge in Berlin by Friedrich the Great, but on condition that he stop publishing his views.Works of Voltaire

At first, the French philosopher Voltaire's arrival at the court of King Frederick the Great was a great success. However, in late 1751, king and philosopher quarreled over Voltaire's pamphlet ''Doctor Akakia'' (French: ''Histoire du Docteur Akakia et du Natif de St Malo''), a satirical essay of a very biting nature directed against Pierre Louis Maupertuis, Maupertuis, the president of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, Royal Academy of Sciences at Berlin - whom Voltaire considered a pretentious pedant. It so excited the anger of King Frederick, the patron of the academy, that he ordered all copies to be seized and burnt by the common hangman. The order was effective in Prussia, but the King could not prevent some 30,000 copies being sold in Paris. In the aftermath, Voltaire had to leave Prussia, though he and King Frederick were later reconciled. Voltaire's works were burnt several times in pre-French Revolution, revolutionary France. In his ''Lettres philosophique'', published in Rouen in 1734, he described British attitudes toward government, literature, and religion, and clearly implied that the British constitutional monarchy was better than the French absolute one – which led to the book being burned. Later, Voltaire's ''Dictionnaire philosophique'', which was originally called the ''Dictionnaire philosophique portatif'', had its first volume, consisting of 73 articles in 344 pages, burnt upon release in June 1764. An "economic pamphlet", ''Man With Forty Crowns'', was ordered to be burnt by the Parlement of Paris, and a bookseller who had sold a copy was pilloried. It is said that one of the magistrates on the case exclaimed, "Is it only his books we shall burn?"Books that offended Qianlong Emperor

China's Qianlong Emperor (1711–1799) embarked on an ambitious program – the Siku Quanshu, largest compilation of books in Chinese history (possibly in human history in general). The enterprise included, however, also the systematic banning and burning of books considered "unfitting" to be included – especially those critical, even by subtle hints, of the ruling Qing dynasty. During this Emperor's nearly sixty years on the throne, the destruction of about 3000 "evil" titles (books, poems, and plays) was decreed, the number of individual copies confiscated and destroyed is variously estimated at tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands. As well as systematically destroying the written works, 53 authors of such works were executed, in some cases by lingering torture or along with their family members. A famous earlier Chinese encyclopedia, ''Tiangong Kaiwu'' ( zh, 天工開物) was included among the works banned and destroyed at this time, and was long considered to be lost forever – but some original copies were discovered, preserved intact, in Japan. The Qianlong Emperor's own masterpiece – the ''Siku Quanshu'', produced only in seven hand-written copies – was itself the target of later book burnings: the copies kept in Zhenjiang and Yangzhou were destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion, and in 1860, during the Second Opium War an Anglo-French expedition force burned most of the copy kept at Beijing's Old Summer Palace. The four remaining copies, though suffering some damage during World War II, are still preserved at four Chinese museums and libraries.Anti-Wilhelm Tell tract (Canton of Uri)

The 1760 tract by Simeon Uriel Freudenberger from Luzern, arguing that Wilhelm Tell was a myth and the acts attributed to him had not happened in reality, was publicly burnt in Altdorf, Uri, Altdorf, capital of the Swiss canton of Canton of Uri, Uri – where, according to the legend, William Tell shot the apple from his son's head.Vernacular Catholic hymn books (at Mainz)

In 1787, an attempt by the Catholic authorities at Mainz to introduce vernacular hymn books encountered strong resistance from conservative Catholics, who refused to abandon the old Latin books and who seized and burned copies of the new German language books.The Libro d'Oro (in the French-ruled Ionian Islands)

With the Treaty of Leoben and the Treaty of Campo Formio in 1797, the First French Republic, French Republic gained the Ionian Islands, hitherto ruled by the Venetian Republic. France proceeded to annex the islands, organize them as the Département in France, départements of Mer-Égée, Ithaque and Corcyre, and introduce there the principles and institutions of the French Revolution – initially getting great enthusiasm among the islands' inhabitants. The abolition of aristocratic privileges was accompanied by the public burning of the ''Libro d'Oro'' – formal directory of nobles in the Republic of Venice which included those of the Ionian Islands.Industrial Revolution period

"The Burned Book" (by Rabbi Nachman of Breslov)

In 1808,Records of the Goa Inquisition (by Portuguese colonial authorities)

In 1812 the Goa Inquisition was suppressed, after hundreds of years in which it had been enacting various kinds of religious persecution in the Portuguese colony of Goa, India. In the aftermath, most of the Goa Inquisition's records were destroyed – a great loss to historians, making it is impossible to know the exact number of the Inquisition's victims.The Code Napoléon (by German Nationalist students)

On October 18, 1817, about 450 students, members of the newly founded German Burschenschaften ("fraternities"), Wartburg festival, came together at Wartburg Castle to celebrate the German victory over Napoleon two years before, condemn conservatism and call for German unity. The Code Napoléon as well as the writings of German conservatives were ceremoniously burned 'in effigy': instead of the costly volumes, scraps of parchment with the titles of the books were placed on the bonfire. Among these was August von Kotzebue's ''History of the German Empires''. Karl Ludwig Sand, one of the students participating in this gathering, would assassinate Kotzebue two years later.William Blake manuscripts (by Frederick Tatham)

The poet William Blake died in 1827, and his manuscripts were left with his wife Catherine Blake, Catherine. After her death in 1831, the manuscripts were inherited by Frederick Tatham, who burned some that he deemed heretical or politically radical. Tatham was an Edward Irving, Irvingite, member of one of the many fundamentalist movements of the 19th century, and opposed to any work that smacked of "blasphemy". At the time, Blake was nearly forgotten, and Tatham could act with impunity. When Blake was re-discovered some decades later and recognized as a major English poet, the damage was already done.Count István Széchenyi's book (by conservative Hungarian nobles)

In 1825 Count István Széchenyi came to the fore as a major Hungary, Hungarian reformer. Though himself a noble, a magnate from one of Hungary's most powerful families, Szechenyi published ''Hitel'' (''Credit''), a book arguing that the nobles' privileges were both morally indefensible and economically detrimental to the nobles themselves. In 1831, angry conservative nobles publicly burned copies of Széchenyi's book.Early braille books (in Paris)

In 1842, officials at the school for the blind in Paris, France, were ordered by its new director, Armand Dufau, to burn books written in the new braille code. After every braille book at the institute that could be found was burned, supporters of the code's inventor, Louis Braille, rebelled against Dufau by continuing to use the code, and braille was eventually restored at the school.Libraries of Buddhist monasteries (during the Taiping Rebellion)

The ''Taiping Heavenly Kingdom'', established by rebels in South China in 1854, sought to replace Confucianism, Buddhism and Chinese folk religion with the Taiping's version of Christianity, God Worshipping, which held that the Taiping leader Hong Xiuquan was the younger brother of Jesus Christ. As part of this policy, the libraries of the Buddhist monasteries were destroyed, almost completely in the case of the Yangtze Delta area. Temples of Daoism, Confucianism, and other traditional beliefs were often defaced. Following the suppression of the Taiping Rebellion, the victorious forces of the Qing dynasty engaged in their own extensive destruction of books and records. It is thought that only a tenth of Taiping-published records survive to this day, as they were mostly destroyed by the Qing in an attempt to rewrite the history of the conflict."The Bonnie Blue Flag" (by Union General Benjamin Butler)

During the American Civil War, when Union Major General Benjamin Butler (politician), Benjamin Butler captured New Orleans he ordered the destruction of all copies of the music for the popular Confederate song "The Bonnie Blue Flag", as well as imposing a $500 fine on A. E. Blackmar who published this music.On the Ancient Cypriots (by Ottoman Authorities)

Following its publication in 1869, the book ''On the Ancient Cypriots'' by Greek Cypriot priest and scholar Ieronymos Myriantheus was banned by the Ottoman Empire, due to its Greek nationalism, Greek Nationalist tendencies, and 460 copies of it were burned. In a punitive measure towards Myriantheus the Ottomans refused to recognize him as Bishop of Kyrenia."Lewd" books (by Anthony Comstock and the NYSSV)

Anthony Comstock founded the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV) in 1873 and over the years burned 15 tons of books, 284,000 pounds of plate, and almost 4 million pictures. The NYSSV was financed by wealthy and influential New York philanthropists. Lobbying the United States Congress also led to the enactment of the Comstock laws.Pedigrees and books of Muslim law and theology (By the Mahdi in Sudan)

After establishing his rule over Mahdist Sudan, Sudan in 1885, Muhammad Ahmad, known as the Mahdi, authorized the burning of lists of pedigrees – which, in his view, accentuated tribalism at the expense of religious unity – as well as books of Muslim law and theology because of their association with the old order which the Mahdi had overthrown.Emily Dickinson's correspondence (on her orders)

Following the death of noted American poet Emily Dickinson in 1890, her sister Lavinia Dickinson burned almost all of her correspondences in keeping with Emily's wishes, but as it was unclear whether the forty notebooks and loose sheets all filled with almost 1800 poems were to be included in this, Lavinia saved these and began to publish the poems that year. When Dickinson's work gained prominence, scholars greatly regretted the loss of the papers which Lavinia Dickinson did burn, and which might have helped elucidate some puzzling references in the poems.Ivan Bloch's research on Russian Jews (by Tsarist Russian government)

In 1901 the Russian Council of Ministers banned a five-volume work on the socio-economic conditions of Russian Jew, Jews in the Russian Empire, the result of a decade-long comprehensive statistical research commissioned by Iwan Bloch, Ivan Bloch. (It was entitled "Comparison of the material and moral levels in the Western Great-Russian and Polish Regions"). The research's conclusions – that Jewish economic activity was beneficial to the Empire – refuted antisemitic demagoguery and were disliked by the government, which ordered all copies to be seized and burned. Only a few survived, circulating as great rarities.Italian Nationalist literature (by Austrian authorities in Trieste)

In the tense period following the Bosnian crisis of 1908–09, the Austria-Hungary, Austrian authorities in Trieste cracked down on the Italian irredentism, Italian Irredentists in the city, who were seeking to end Austrian rule there and annex Trieste to Italy (which would actually happen ten years later, at the end of World War I). A very large quantity of Italian-language books and periodicals whose contents were deemed "subversive" were confiscated and consigned to destruction. The authorities had the condemned material meticulously weighted, it was found to measure no less than 4.7 metric tons. Thereupon, on February 13, 1909, the books and periodicals were officially burned at the Servola blast furnaces. The site of the book burnings was very near the home of the writer Italo Svevo, though Svevo's own works were spared. (Servola is a suburb of Trieste.)World War I and interwar era

Books in Serbian (by World War I Bulgarian Army)

In the aftermath of the Serbian defeat in the Serbian Campaign of World War I, the region of Old Serbia came under the control of Bulgarian occupational authorities. Bulgaria engaged in a campaign of cultural genocide. Serbian priests, professors, teachers and public officials were deported into prison camps in pre–war Bulgaria or executed; they were later replaced by their Bulgarian counterparts. The use of the Serbian language was banned. Books in Serbian were confiscated from libraries, schools and private collections to be burned publicly. Books deemed to be of particular value were selected by Bulgarian ethnographers and sent back into Bulgaria.''Valley of the Squinting Windows'' (at Delvin, Ireland)

In 1918 the ''Valley of the Squinting Windows'', by Brinsley MacNamara, was burned in Delvin, Ireland. MacNamara never returned to the area, his father James MacNamara was boycotted and subsequently emigrated, and a court case was even sought. The book criticised the village's inhabitants for being overly concerned with their image towards neighbours, and although it called the town "Garradrimna," geographical details made it clear that Delvin was meant.George Grosz's cartoons (by court order in Weimar Germany)

In June 1920 the left-wing German cartoonist George Grosz produced a lithographic collection in three editions entitled ''Gott mit uns''. A satire on German society and the counterrevolution, the collection was swiftly banned. Grosz was charged with insulting the Reichswehr, army, which resulted in a court order to have the collection destroyed. The artist also had to pay a 300 Deutsche Mark, German Mark fine.Margaret Sanger's ''Family Limitation'' (by British court order)

In 1923 the anarchist Guy Aldred and his partner and co-worker Rose Witcop, a birth control activist, published together a British edition of Margaret Sanger's ''Family Limitation'' – a key pioneering work on the subject. They were denounced by a London magistrate for this "indiscriminate" publication. The two lodged an appeal, strongly supported in their legal struggle by Dora Russell – who, with her husband Bertrand Russell and John Maynard Keynes, paid the legal costs.Russell, Dora, (1975) ''The Tamarisk Tree'' However, it was to no avail. Despite expert testimony from a consultant to Guy's Hospital and evidence at the appeal that the book had only been sold to those aged over twenty-one, the court ordered the entire stock to be destroyed.''The Times'', February 12, 1923, p.5Theodore Dreiser's works (at Warsaw, Indiana)

Trustees of Warsaw, Indiana ordered the burning of all the library's works by local author Theodore Dreiser in 1935.Works of Goethe, Shaw, and Freud (by Metaxas dictatorship in Greece)

Ioannis Metaxas, who held dictatorial power in Greece between 1936 and 1941, conducted an intensive campaign against what he considered ''Anti-Greek literature'' and viewed as ''dangerous to the national interest''. Targeted under this definition and put to the fire were not only the writings of dissident Greek writers, but even works by such authors as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Goethe, George Bernard Shaw, Shaw, and Sigmund Freud, Freud.Books, pamphlets and pictures (by Soviet authorities)

In his ''Open Letter to Stalin'' Old Bolshevik and former Soviet diplomat Fyodor Raskolnikov alleges that Soviet Union, Soviet libraries began circulating long lists of books, pamphlets and pictures to be burnt on sight, following Joseph Stalin's ascension to power. Those lists include the names of authors whose works were deemed as undesirable. Raskolnikov was surprised to find his work on the October Revolution in one of those lists. The lists contained numerous books from the West which were deemed decadent.Pompeu Fabra's library (by Franco's troops)

In 1939, shortly after the surrender of Barcelona, Franco's troops burned the entire library of Pompeu Fabra, the main author of the normative reform of contemporary Catalan language, while shouting "¡Abajo la inteligencia!" (Down with the intelligentsia!)World War II

Jewish, anti-Nazi and "degenerate" books (by the Nazis)

Jewish books in Alessandria (by pro-Nazi mob)

On December 13, 1943, in Alessandria, Italy, a mob of supporters of the German-imposed Italian Social Republic attacked the synagogue of the city's small Jewish community, on Via Milano. Books and manuscripts were taken out of the synagogue and set on fire at Piazza Rattazzi. The burning of the Jewish books was a prelude to a mass arrest and deportation of the Jews themselves, most of whom perished in Auschwitz.André Malraux's manuscript (by the Gestapo)

During World War II the French writer and anti-Nazi resistance fighter André Malraux worked on a long novel, ''The Struggle Against the Angel'', the manuscript of which was destroyed by the Gestapo upon his capture in 1944. The name was apparently inspired by the Jacob story in the Bible. A surviving opening part named ''The Walnut Trees of Altenburg'', was published after the war.Manuscripts and books in Warsaw, Poland (by the Nazis)

Books in the National Library of Serbia (by World War II German bomber planes)

On April 6, 1941, during World War II, German bomber planes under orders by Nazi Germany specifically targeted the National Library of Serbia in Belgrade. The entire collection was destroyed, including 1,300 ancient Cyrillic manuscripts and 300,000 books.Cold War era and 1990s

The books of Knut Hamsun (in post-World War II Norway)

Following the liberation of Norway from Nazi occupation in 1945, angry crowds burned the books of Knut Hamsun in public in major Norwegian cities, due to Hamsun's having collaborated with the Nazis.Post-World War II Germany

On May 13, 1946, the Allied Control Council issued a directive for the confiscation of all media that could supposedly contribute to Nazism or militarism. As a consequence a list was drawn up of over 30,000 titles, ranging from school textbooks to poetry, which were then banned. All copies of books on the list were to be confiscated and destroyed; the possession of a book on the list was made a punishable offence. All the millions of copies of these books were to be confiscated and destroyed. The representative of the Military Directorate admitted that the order was no different in intent or execution from Nazi book burnings. All confiscated literature was reduced to pulp instead of burning. In August 1946 the order was amended so that "In the interest of research and scholarship, the Zone Commanders (in Berlin the Komendantura) may preserve a limited number of documents prohibited in paragraph 1. These documents will be kept in special accommodation where they may be used by German scholars and other German persons who have received permission to do so from the Allies only under strict supervision by the Allied Control Authority.Books in Kurdish (in north Iran)

Following the suppression of the pro-Soviet Kurdish Republic of Mahabad in north Iran in December 1946 and January 1947, members of the victorious Iranian Army burned all Kurdish language, Kurdish-language books that they could find, as well as closing down the Kurdish printing press and banning the teaching of Kurdish.Comic book burnings, 1948

In 1948, children – overseen by priests, teachers, and parents – publicly burned several hundred comic books in both Spencer, West Virginia, and Binghamton, New York. Once these stories were picked up by the national press wire services, similar events followed in many other cities.Books by Shen Congwen (by Chinese booksellers)

Around 1949, the books that Shen Congwen (pseudonym of Shen Yuehuan) had written in the period 1922–1949 were banned in the Republic of China and both banned and subsequently burned by booksellers in the People's Republic of China.Judaica collection at Birobidzhan (by Stalin)

As part of Joseph Stalin's efforts to stamp out Jewish culture in the Soviet Union in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Judaica collection in the library of Birobidzhan, capital of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast on the Chinese border, was burned.Romanian literature (by the Romanian Workers' Party)

In the 1950s, the Romanian Communist Party#Romanian Workers' Party (1948–1965), Romanian Workers' Party had started purging the libraries of the Socialist Republic of Romania#Romanian People's Republic, Romanian People's Republic ( ro, Republica Populară Romînă, ''RPR''), by burning any books mentioning Bessarabia or the Bukovina and German language, German and Italian language, Italian translations of Romanian literature. The entire contents of the Casa Școalelor had been emptied, with books on national popular culture and religious works were burned. A librarian of the Romanian Academy, Academy, Barbu Lăzăreanu, was put in charge of maps, documents, photographs, the unique lexicographical file of the Romanian language, which all were proving the Latin origin of Romanian. Displeasing the Slavic committee that had passed on them, they were burned. 762 Romanian literary works were withdrawn from circulation, including those of Liviu Rebreanu, Ioan Alexandru Brătescu-Voinești and Octavian Goga. The purged books and treasures were replaced with millions of books and pamphlets. Cartea Rusă alone issued 3,701,300 copies of Romanian translations of 174 Russian language, Russian books, with additional 329,050 copies translated in Hungarian language, Hungarian, German language, German, Serbian language, Serbian and Turkish language, Turkish. The purging of the books was led by Petre Constantinescu-Iași, Mihail Roller, Mihai Roller, Barbu Lăzăreanu and Emil Petrovici.Mordecai Kaplan's publications (by Union of Orthodox Rabbis)

In 1954, the rabbi Mordecai Kaplan was excommunicated from Orthodox Judaism in the United States, and his works were publicly burned at the annual gathering of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis. Zachary Silver,A look back at a different book burning

" ''The Forward'', June 3, 2005

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

Communist books were burned by the revolutionaries during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, when 122 communities reported book burnings.Memoirs of Yrjö Leino (by Finnish government, under Soviet pressure)

Yrjö Leino, a Communist activist, was Minister of the Interior (Finland), Finnish Minister of the Interior in the crucial 1945–1948 period. In 1948 he suddenly resigned for reasons which remain unclear and went into retirement. Leino returned to the public eye in 1958 with his memoirs of his time as Minister of the Interior. The manuscript was prepared in secret – even most of the staff of the publishing company Tammi (publishing company), Tammi were kept in ignorance – but the project was revealed by Leino because of an indiscretion just before the planned publication. It turned out the Soviet Union was very strongly opposed to publication of the memoirs. The Soviet Union's Chargé d'affaires in Finland Ivan Filippov (Ambassador Viktor Lebedev had suddenly departed from Finland a few weeks earlier on October 21, 1958) demanded that Prime Minister Karl-August Fagerholm's government prevent the release of Leino's memoirs. Fagerholm said that the government could legally do nothing, because the work had not yet been released nor was there censorship in Finland. Filippov advised that if Leino's book was published, the Soviet Union would draw "serious conclusions". Later the same day Fagerholm called the publisher, Untamo Utrio, and it was decided that the January launch of the book was to be cancelled. Eventually, the entire print run of the book was destroyed at the Soviet Union's request. Almost all of the books – some 12,500 copies – were burned in August 1962 with the exception of a few volumes which were furtively sent to political activists. Deputy director of Tammi Jarl Hellemann later argued that the fuss about the book was completely disproportionate to its substance, describing the incident as the first instance of Finnish self-censorship motivated by concerns about relations to the Soviet Union. The book was finally published in 1991, when interest in it had largely dissipated.Brazil, military coup, 1964

Following the 1964 Brazilian coup d'état, General Justino Alves Bastos, commander of the Third Army, ordered, in Rio Grande do Sul, the burning of all "subversive books". Among the books he branded as subversive was Stendhal's ''The Red and the Black''. Stendhal's was written in criticism of the situation in France under the reactionary regime of the Bourbon Restoration in France, Restored Bourbon monarchy (1815-1830). Evidently, General Bastos felt some of this could also apply to life in Brazil under the right-wing military junta.Religious, anti-Communist and genealogy books (in the Cultural Revolution)

It is the Chinese tradition to record family members in a book, including every male born in the family, who they are married to, etc. Traditionally, only males' names are recorded in the books. During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), many such books were forcibly destroyed or burned to ashes, because they were considered by the Chinese Communist Party as among the Four olds, Four Old Things to be eschewed. Also many copies of classical works of Chinese literature were destroyed, though – unlike the genealogy books – these usually existed in many copies, some of which survived. Many copies of theSiné's ''Massacre'' (during power struggle in "Penguin Books")

In 1965, the British publishing house Penguin Books was torn by an intense power struggle, with chief editor Tony Godwin and the board of directors attempting to remove the company founder Allen Lane. One of the acts taken by Lane in an effort to retain his position was to steal and burn the entire print run of the English edition of ''Massacre'' by the French cartoonist Siné, whose content was reportedly "deeply offensive".Beatles burnings – Southern USA, 1966

John Lennon, member of the popular music group The Beatles, sparked outrage from religious conservatives in the Southern 'Bible Belt' states due to his quote 'More popular than Jesus, The Beatles are more popular than Jesus' from an interview he had done in England five months previous to the Beatles' 1966 US Tour (their final tour as a group). Disc Jockeys, evangelists, and the Ku Klux Klan implored the local public to bring their Beatles records, books, magazines, posters and memorabilia to Beatles bonfire burning events.Leftist books in Chile during the Pinochet dictatorship

After the victory of Augusto Pinochet's forces in the Chilean coup of 1973, bookburnings of Marxist and other works ensued. Journalist Carlos Rama reported in February 1974 that up to that point, destroyed works included: the handwritten Chilean Declaration of Independence by Bernardo O'Higgins, thousands of books of Editora Nacional Quimantú including the ''Complete Works'' of Che Guevara, thousands of books in the party headquarters of the Chilean Socialist Party and MAPU, personal copies of works by Marx, Lenin, and anti-fascist thinkers, and thousands of copies of newspapers and magazines favorable to Salvador Allende including ''Chile Today''. In some instances, even books on Cubism were burned because ignorant soldiers thought it had to do with the Cuban Revolution.

After the victory of Augusto Pinochet's forces in the Chilean coup of 1973, bookburnings of Marxist and other works ensued. Journalist Carlos Rama reported in February 1974 that up to that point, destroyed works included: the handwritten Chilean Declaration of Independence by Bernardo O'Higgins, thousands of books of Editora Nacional Quimantú including the ''Complete Works'' of Che Guevara, thousands of books in the party headquarters of the Chilean Socialist Party and MAPU, personal copies of works by Marx, Lenin, and anti-fascist thinkers, and thousands of copies of newspapers and magazines favorable to Salvador Allende including ''Chile Today''. In some instances, even books on Cubism were burned because ignorant soldiers thought it had to do with the Cuban Revolution.

Books burned by at order of school board in Drake, North Dakota, USA

On November 8, 1973, the custodian at Drake's elementary/high school used the school's furnace to burn 32 copies of Kurt Vonnegut's ''Slaugherhouse Five,'' at the order of the school board after they "deemed the novel profane and therefore unsuitable for use in class." Other books reported to have been burned were ''Deliverance'' by James Dickey, and a short story anthology with stories from Joseph Conrad, William Faulkner, and John Steinbeck.Book burning caused by Viet Cong in South Vietnam

Following The Fall of Saigon, Viet Cong gained nominal authority in South Vietnam and conducted several book burnings along with eliminating any cultural forms of South Vietnam. This act of destruction was made since the Vietnamese Communists condemned those values were corruptible ones shaped by "puppet government" (derogatory words to indicate Republic of Vietnam) and American Imperialism.''From the Noble Savage to the Noble Revolutionary'' (Venezuela, 1976)

In 1976 detractors of Venezuelan Liberalism, liberal writer Carlos Rangel publicly burned copies of his book ''From the Noble Savage to the Noble Revolutionary'' in the year of its publication at the Central University of Venezuela.New Testament (Jerusalem, 1980)

On 23 March 1980, Yad L'Achim, an Orthodox Judaism outreach, Orthodox Jewish Proselytization and counter-proselytization of Jews, counter-missionary organisation that was at the time a beneficiary of subsidies from the Ministry of Religious Services, Israeli Ministry of Religion, ceremonially incinerated hundreds of copies of the''The Burning of Jaffna Library''

Took place on the night of June 1, 1981, when an organized mob of Sinhalese individuals went on a rampage, burning the library to destroy Tamil language Literary works against Tamils. It was one of the most violent examples of ethnic biblioclasm of the 20th century. At the time of its destruction, the library was one of the biggest in Asia, containing over 97,000 books and manuscripts.Sikh Reference Library (Amritsar, 1984)

The Sikh Reference Library in Amritsar, a collection of rare books, newspapers, manuscripts, and other literary works related to Sikhism and India, was looted and incinerated by Indian troops during the 1984 Operation Blue Star. The missing literature has not been recovered to this day and are presumbed to be lost. The library hosted a vast collection of an estimated 20,000 literary works just before the destruction, including 11,107 books, 2,500 manuscripts, newspaper archives, historical letters, documents/files, and others. Most of the literature was written in the Punjabi-language and related to Sikhism, but there were also Hindi, Assamese, Bengali, Sindhi, English, and French works touching upon various topics.''The Satanic Verses'' (worldwide)

The 1988 publication of the novel ''The Satanic Verses'', by Salman Rushdie, was followed by angry demonstrations and riots around the world by followers of political Islam who considered it blasphemy, blasphemous. In the United Kingdom, book burnings were staged in the cities of Bolton and Bradford. In addition, five UK bookstores selling the novel were the target of bombings, and two bookstores in Berkeley, California were firebombing, firebombed. The author was condemned to death by various Islamist clerics and lives in hiding.Central University Library (Bucharest, 1989)

During the Romanian Revolution of December 1989, the Central University Library, Bucharest, Central University Library of Bucharest was burned down in uncertain circumstances and over 500,000 books, along with about 3,700 manuscripts, were destroyed.The Central University Library of Bucharestofficial site: "the History".

, Evenimentul Zilei, 3 June 2010.

Oriental Institute in Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1992)

On 17 May 1992, the Oriental Institute in Sarajevo, Oriental Institute in Siege of Sarajevo, besieged city of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, was targeted by Yugoslav People's Army#Dissolution, JNA and Serb nationalists artillery, and repeatedly hit with a barrages of incendiary ammunition fired from positions on the hills overlooking the city center. The Institute occupied the top floors of a large, four-storey office block squeezed between other buildings in a densely built neighborhood, with no other buildings being hit. After catching the fire, the institute was completely burned out and most of its collections destroyed by blaze. The collections of the institute were among the richest of its kind, containing Oriental manuscripts centuries old and written about the subjects in wide varieties of fields, in Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Hebrew and local (native Bosnian language written in Arabic script), other languages and many different scripts and in many different geographical location around the world. The losses included 5,263 bound manuscripts, as well as tens of thousands of Ottoman-era documents of various kind. Only about 1% of Institute materials was saved.National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992)

On August 25, 1992, the National and University Library of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina was firebombed and destroyed by Serbian nationalists. Almost all the contents of the library were destroyed, including more than 1.5 million books that included 4,000 rare books, 700 manuscripts, and 100 years of Bosnian newspapers and journals.Abkhazian Research Institute of History, Language and Literature and National Library of Abkhazia (by Georgian troops)

Georgian troops entered Abkhazia on August 14, 1992, sparking a 14-month war. At the end of October, the Abkhazian Research Institute of History, Language and Literature named after Dmitry Gulia, which housed an important library and archive, was torched by Georgian troops; also targeted was the capital's public library. It seems to have been a deliberate attempt by the Georgian paramilitary soldiers to wipe out the region's historical record.The Nasir-i Khusraw Foundation in Kabul (by the Taliban regime)

In 1987, the Nasir-i Khusraw Foundation was established in Kabul, Afghanistan due to the collaborative efforts of several civil society and academic institutions, leading scholars and members of theMorgh-e Amin publication house in Tehran (by Islamic extremists)

Some days after publishing a novel entitled ''The Gods Laugh on Mondays'' by Iranian novelist Reza Khoshnazar, men came at night saying they are Islamic building inspectors and torched the publisher's book shop on or around August 22 or 23, 1995.21st century

Abu Nuwas poetry (by Egyptian Ministry of Culture)

In January 2001, the Ministry of Culture (Egypt), Egyptian Ministry of Culture ordered the burning of some 6,000 books of homoerotic poetry by the well-known 8th century Persian-Arab poet Abu Nuwas, even though his writings are considered classics of Arab literature.Iraq's national library, Baghdad 2003

Following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Iraq National Library and Archive, Iraq's national library and the Islamic library in centralUnited Talmund Torah School Library, Montreal 2004

On the morning of April 5, 2004, 18-year-old Sleiman El-Merhebi firebombed a school library of the United Talmud Torahs of Montreal, burning its 10,000 volume collection. Reconstruction and other indirect costs amounted to 600,000 Canadian dollars.Dan Brown's ''The Da Vinci Code'', Italy 2006

On May 20, 2006, at noon, two communal Italian councillors, Stefano Gizzi and , staged a burning of a copy of ''The Da Vinci Code'' after the The Da Vinci Code (film), film of the same name premiered, in the square of Italian town Ceccano.The Diary of Anne Frank during a midsummer's party, Germany 2006

On June 24, 2006, a bunch of men, aged between 24 and 28, threw a Flag of the United States, United States flag and a copy of The Diary of a Young Girl, The Diary of Anne Frank into a bonfire, first the flag, then the book, during a midsummer's party in German village Pretzien. They were supposedly members of a far-right group called Heimat Bund Ostelbien (East Elbian Homeland Federation), who also organized the party.Harry Potter books (in various American cities)

There have been several incidents of Harry Potter books being burned, including those directed by churches at Alamogordo, New Mexico and Charleston, South Carolina in 2006. More recently books have been burnt in response to J.K. Rowling's stance on trans rights and comments on Donald Trump.Inventory of Prospero's Books (by proprietors Tom Wayne and W.E. Leathem)

On May 27, 2007, Tom Wayne and W.E. Leathem, the proprietors of Prospero's Books, a used book store in Kansas City, Missouri, publicly burned a portion of their inventory to protest what they perceived as society's increasing indifference to the printed word. The protest was interrupted by the Kansas City Fire Department on the grounds that Wayne and Leathem had failed to obtain the required permits.New Testaments in city of Or Yehuda, Israel

In May 2008, a "fairly large" number of New Testaments were burned in Or Yehuda, Israel. Conflicting accounts have the deputy mayor of Or Yehuda, Uzi Aharon (of Haredi party Shas), claiming to have organized the burnings or to have stopped them. He admitted involvement in collecting New Testaments and "Messianic propaganda" that had been distributed in the city. The burning apparently violated Israeli laws about destroying religious items.Non-approved Bibles, books and music in Canton, North Carolina

The Amazing Grace Baptist Church of Canton, North Carolina, headed by Pastor Marc Grizzard, intended to hold a book burning on Halloween 2009. The church, being a King James Only movement, King James Version exclusive church, held all other translations of the Bible to be heretical, and also considered both the writings of Christian writers and preachers such as Billy Graham and T.D. Jakes and most musical genres to be heretical expressions. However, a confluence of rain, oppositional protesters and a state environmental protection law against open burning resulted in the church having to retreat into the edifice to ceremoniously tear apart and dump the media into a trash can (as recorded on video which was submitted to People For the American Way's Right Wing Watch blog); nevertheless, the church claimed that the book "burning" was a success.Bagram Bibles

In 2009 the US military burned Bibles in Pashto and Dari language, Dari that were part of an unauthorized program to Proslytization, proselytize Christianity in Afghanistan.2010–11 Florida Qur'an burning and related burnings

On September 11, 2010: *Fred Phelps burned a Qur'an with the American flag at the Westboro Baptist Church *Bob Old and another preacher burned a Qur'an in Nashville, Tennessee *A New Jersey transit worker burned a few pages of a Qur'an at the Ground Zero Mosque in Manhattan *Burned Qur'ans were found in Knoxville, Tennessee, East Lansing, Michigan, Springfield, Tennessee, and Chicago, Illinois.''Operation Dark Heart'', memoir by Anthony Shaffer (by the U. S. Dept. of Defense)

On September 20, 2010, the Pentagon bought and burned 9,500 copies of ''Operation Dark Heart'', nearly all the first run copies for supposedly containing classified information.Gaddafi's Green Book

During the 2011 Libyan Civil War, Libyan Civil War, copies of Muammar Gaddafi's The Green Book (Muammar Gaddafi), Green Book were burned by anti-Gaddafi demonstrators.Suspected Colorado City incident

Sometime during the weekend of April 15–17, 2011, books and other items designated for a new public library in the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints polygamous community Colorado City, Arizona, Colorado City, Arizona were removed from the facility where they had been stored and burned nearby. A lawyer for some FLDS members has stated that the burning was the result of a cleanup of the property and that no political or religious statement was intended, however the burned items were under lock and key and were not the property of those who burned them.Lawrence Hill books covers in Amsterdam 2011

On June 22, 2011, a group of Dutch activists torched the cover of Lawrence Hill's The Book of Negroes (novel), The Book of Negroes (translated as ''Het negerboek'' in Dutch language, Dutch) in front of the National Slavery Monument ( nl, Slavernijmonument) of Amsterdam over the use of the term negro in the title, which they found to be offensive. On the same day, Greg Hollingshead, chair of the Writers' Union of Canada called the act "censorship at its worst", while recognizing the sensitivity over the use of the word "negro" in book titles.Qur'ans in Afghanistan

On February 22, 2012, four copies of the Qur'an were burned at Bagram Airfield due to being among 1,652 books slated for destruction. The remaining books, which officials claimed were being used for communication among extremists, were saved and put into storage.Fishery, ocean and environmental library books throughout Canada

In 2013, Canadian scientists claimed that the closure of several scientific libraries by the 28th Canadian Ministry, Harper Cabinet led to them being thrown into dumpsters, scavenged by citizens, thrown in landfills or burned.Anti-climate change book at San Jose State University

In May 2013, two San Jose State University professors, department chair Alison Bridger, PhD and associate professor Craig Clements, PhD, were photographed holding a match to a book they disagreed with, ''The Mad, Mad, Mad World of Climatism'', by Steve Goreham. The university initially posted it on their website, but then took it down.Theology library purge in North Carolina

Traditionalist Catholicism, Traditionalist Catholic seminarians purged a Boone, North Carolina theology library in 2017 of works they considered heretical, including the writing of Henri Nouwen and Thomas Merton. The books were burned. Parishioners uncomfortable with the radical behavior of local church officials celebrate Catholic mass in an automobile repair shop instead of the church building.Southwestern Ontario schools book burning

The Conseil scolaire catholique Providence that oversees elementary and secondary schools in Southwestern Ontario held a "flame purification" ceremony in 2019, burning and burying 5,000 books from 30 Southwestern Ontario French-language schools for depicting racist stereotypes of Indigenous peoples of the Americas. ''Tintin in America'' and ''Asterix and the Great Crossing'' were among the burned books.Harry Potter and other books

On March 31, 2019, a Catholic priest in Gdańsk, Poland, burned books such as ''Harry Potter'' and novels in the ''Twilight (novel series), Twilight'' series. The other objects were an umbrella with a Hello Kitty pattern, an elephant figurine, a tribal mask and a figurine of a Hindu god.Zhenyuan, China

In October 2019, officials at a library in the Gansu, Gansu Province reportedly burned 65 books that were banned by the regime.Tennessee Global Vision Bible Church book burning

On February 2, 2022, Pastor Greg Locke of the Global Vision Bible Church in Mount Juliet, Tennessee, led a book burning event with attendees also throwing books and other media into the fire. The burning was livestreamed on Facebook. The burn pile was fed partially with dozens of wood forklift pallet, pallets. At one point Locke claimed that the fire department was trying to put the fire out but his security team was successfully blocking their access. Along with contributions from the crowd, a dumpster full of books was unveiled and burned by Locke and attendees. Locke claimed it was his and the churches "biblical right" to "burn....cultic materials that they deem are a threat to their religious rights and freedoms and belief systems." On Instagram, Locke wrote that "anything tied to the Masonic Lodge needs to be destroyed."See also

* List of books banned by governments * Book burning * Censorship * Destruction of libraries * ''Fahrenheit 451'' * Lost literary workReferences

Informational notes Citations Bibliography * *External links

The books have been burning – World – CBC News

A Brief History of Book Burning, From the Printing Press to Internet Archives – Smithsonian Magazine

{{Books Book censorship History of books Historical negationism Events relating to freedom of expression Protest tactics, * List of book-burning incidents Book burnings Literature lists, book-burning