Liber Linteus Zagrabiensis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The (

The (

In 1848, Mihajlo Barić (1791–1859), a low ranking

In 1848, Mihajlo Barić (1791–1859), a low ranking

* Roncalli, F. (1978-1980) "Osservazioni sui ''libri lintei'' etruschi" in ''Rendiconti. Pontificia Accademia'' 51-52 982 pp. 3-21. * Rix, H. (1985) "Il ''liber linteus'' di Zagabria" in ''Scrivere etrusco'' pp. 17-52. * Pallottino, M. (1986) "Il libro etrusco della uimmia di Zagabria. Significato e valore storico e linguistico del documento" in ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 19, pp. 1-5. * Pfiffig, A. J. (1986) "Zur Heuristik des ''Liber linteus zagrabiensis''" ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 19, pp. 9–13. * Flury-Lemberg, M. (1986) "Die Rekonstruktion des ''liber linteus Zagrabiensis'' oder die Mumienbinden von Zagreb," ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 19, pp. 73–79 * Mirnik, I., Rendić-Miočević, A. (1996) "Liber linteus Zagrbiensis I" ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 19, pp. 41–71. * Mirnik, I., Rendić-Miočević, A. (1997) "Liber linteus Zagrbiensis II" ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 20, pp. 31–48. * Rix, H. (1991) ''Etruskische Texte: Editio minor.'' I-II, Tübingen. * Steinbauer, D.H. (1999) ''Neues Handbuch des Etruskischen'' (Studia Classica, Band 1) St. Katharinen. * * van der Meer, L. B. (2007) ''Liber linteus zagrabiensis. The Linen Book of Zagreb. A Comment on the Longest Etruscan Text''. Louvain/Dudley, MA . * * Belfiore, V. (2010) ''Il liber linteus di Zagabria: testualità e contenuto''. Biblioteca di ''Studi Etruschi'' 50 Pisa-Roma. . * van der Meer, L. B. (2011) Review of V. Belfiore's ''Il liber linteus di Zagabria'' (2010) in ''Bryn Mawr Classical Review'' 1.3

* Meiser, G. (2012) "Umbrische Kulte im Liber Linteus?", in ''Kulte, Riten, religise Vorstellung bei den Etruskern, a cura di P.Amman'', Wien, 163-172

* Woudhuizen, F. C. (2013) ''The Liber linteus: A Word for Word Commentary to and Translation of the Longest Etruscan Text. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft, Neue Folge, Bd 5.'' Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen der Universität Innsbruck Bereich Sprachwissenschaft. ISBN 9783851242317. * Tikkanen, K. W. (2014) Review of Woudhuizen, F. C. (2013) in ''Bryn Mawr Classical Review'' 11.1

* Dupraz, E. (2019) ''Tables Eugubines ombriennes et Livre de lin étrusque: Pour une reprise de la comparaison'' Herman: Paris .

The (

The (Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

for "Linen Book of Zagreb", also rarely known as , "Book of Agram") is the longest Etruscan __NOTOC__

Etruscan may refer to:

Ancient civilization

*The Etruscan language, an extinct language in ancient Italy

*Something derived from or related to the Etruscan civilization

**Etruscan architecture

**Etruscan art

**Etruscan cities

**Etruscan ...

text and the only extant linen

Linen () is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

Linen is very strong, absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these properties, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also ...

book, dated to the 3rd century BCE. (The second longest, Tabula Capuana

The ''Tabula Capuana'' ("Tablet from Capua"; Ital. ''Tavola Capuana''), is an ancient terracotta slab, , with a long inscribed text in Etruscan, dated to about 470 bce, apparently a ritual calendar. About 390 words are legible, making it the se ...

, also seems to be a ritual calendar.) Much of it is untranslated because of the lack of knowledge about the Etruscan language, though the words and phrases which can be understood indicate that the text is most likely a ritual calendar

A calendar is a system of organizing days. This is done by giving names to periods of time, typically days, weeks, months and years. A date is the designation of a single and specific day within such a system. A calendar is also a physi ...

. Miles Beckwith points out with regard to this text that "in the last thirty or forty years, our understanding of Etruscan has increased substantially," and L. Bouke van der Meer Lammert Bouke van der Meer (born 1945 in Leeuwarden, Friesland) is a Dutch classicist and classical archaeologist specialized in Etruscology. He studied classics and archaeology at the University of Groningen, and received his Ph.D. from the same ...

has published a word-by-word analysis of the entire text.

The fabric of the book was preserved when it was used for mummy wrappings in Ptolemaic Egypt. The mummy was bought in Alexandria in 1848 and since 1867 both the mummy and the manuscript have been kept in Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slop ...

, Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

, now in a refrigerated room at the Archaeological Museum

An archaeology museum is a museum that specializes in the display of archaeological

Types

Many archaeology museum are in the open air, such as the Ancient Agora of Athens and the Roman Forum. Others display artifacts inside buildings, such as Na ...

.

History of discovery

In 1848, Mihajlo Barić (1791–1859), a low ranking

In 1848, Mihajlo Barić (1791–1859), a low ranking Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = "Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capit ...

n official in the Hungarian Royal Chancellery, resigned his post and embarked upon a tour of several countries, including Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. While in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, he purchased a sarcophagus

A sarcophagus (plural sarcophagi or sarcophaguses) is a box-like funeral receptacle for a corpse, most commonly carved in stone, and usually displayed above ground, though it may also be buried. The word ''sarcophagus'' comes from the Greek ...

containing a female mummy, as a souvenir of his travels. Barić displayed the mummy at his home in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, standing it upright in the corner of his sitting room. At some point he removed the linen wrappings and put them on display in a separate glass case, though it seems he had never noticed the inscriptions or their importance.

The mummy remained on display at his home until his death in 1859, when it passed into possession of his brother Ilija, a priest in Slavonia

Slavonia (; hr, Slavonija) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria, one of the four historical regions of Croatia. Taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with five Croatian counties: Brod-Posavina, Osijek-Baranja ...

. As he took no interest in the mummy, he donated it in 1867 to the State Institute of Croatia, Slavonia, and Dalmatia in Zagreb

Zagreb ( , , , ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, northwest of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slop ...

(the present-day Archaeological Museum in Zagreb

The Archaeological Museum ( hr, Arheološki muzej u Zagrebu) in Zagreb, Croatia is an archaeological museum with over 450,000 varied artifacts and monuments, gathered from various sources but mostly from Croatia and in particular from the surround ...

). Their catalogue described it as follows:

:''Mummy of a young woman (with wrappings removed) standing in a glass case and held upright by an iron rod. Another glass case contains the mummy's bandages which are completely covered with writing in an unknown and hitherto undeciphered language, representing an outstanding treasure of the National Museum.''

The mummy and its wrappings were examined the same year by the German Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch, who noticed the text, but believed them to be Egyptian hieroglyph

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1,00 ...

s. He did not undertake any further research on the text, until 1877, when a chance conversation with Richard Burton about runes

Runes are the letter (alphabet), letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, a ...

made him realise that the writing was not Egyptian. They realised the text was potentially important, but wrongly concluded that it was a transliteration of the Egyptian Book of the Dead

The ''Book of the Dead'' ( egy, 𓂋𓏤𓈒𓈒𓈒𓏌𓏤𓉐𓂋𓏏𓂻𓅓𓉔𓂋𓅱𓇳𓏤, ''rw n(y)w prt m hrw(w)'') is an ancient Egyptian funerary text generally written on papyrus and used from the beginning of the New Kingdom ...

in the Arabic script

The Arabic script is the writing system used for Arabic and several other languages of Asia and Africa. It is the second-most widely used writing system in the world by number of countries using it or a script directly derived from it, and the ...

.

In 1891, the wrappings were transported to Vienna, where they were thoroughly examined by Jacob Krall, an expert on the Coptic language

Coptic (Bohairic Coptic: , ) is a language family of closely related dialects, representing the most recent developments of the Egyptian language, and historically spoken by the Copts, starting from the third-century AD in Roman Egypt. Coptic ...

, who expected the writing to be either Coptic, Libyan or Carian. In 1892, Krall was the first to identify the language as Etruscan and reassemble the strips. It was his work that established that the linen wrappings constituted a manuscript written in Etruscan.

At first, the provenance and identity of the mummy were unknown, due to the irregular nature of its excavation and sale. This led to speculation that the mummy may have had some connection to either the or the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, rou ...

. But a papyrus buried with her proves that she was Egyptian and gives her identity as Nesi-hensu, the wife of Paher-hensu, a tailor from Thebes. She was 30–40 years old at the time of her death, and wore a necklace, with traces of flowers and gold in her hair. Among the fragments of the accompanying wreath, there was a cat skull.

Text

Date and origin

On paleographic grounds, the manuscript is dated to approximately 250 BC (though carbon dating put manufacture of the linen textile itself at 390 BC +/- 45 years). Certain local gods mentioned within the text allow the 's place of production to be narrowed to a small area in the southeast ofTuscany

Tuscany ( ; it, Toscana ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of about 3.8 million inhabitants. The regional capital is Florence (''Firenze'').

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, art ...

near Lake Trasimeno

Lake Trasimeno ( , also ; it, Lago Trasimeno ; la, Trasumennus; ett, Tarśmina), also referred to as Trasimene ( ) or Thrasimene in English, is a lake in the province of Perugia, in the Umbria region of Italy on the border with Tuscany. Th ...

, where four major Etruscan cities were located: modern day Arezzo

Arezzo ( , , ) , also ; ett, 𐌀𐌓𐌉𐌕𐌉𐌌, Aritim. is a city and ''comune'' in Italy and the capital of the province of the same name located in Tuscany. Arezzo is about southeast of Florence at an elevation of above sea level. ...

, Perugia

Perugia (, , ; lat, Perusia) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber, and of the province of Perugia.

The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and part o ...

, Chiusi

Chiusi (Etruscan: ''Clevsin''; Umbrian: ''Camars''; Ancient Greek: ''Klysion'', ''Κλύσιον''; Latin: ''Clusium'') is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Siena, Tuscany, Italy.

History

Clusium (''Clevsin'' in Etruscan) was one of t ...

and Cortona

Cortona (, ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Arezzo, in Tuscany, Italy. It is the main cultural and artistic centre of the Val di Chiana after Arezzo.

Toponymy

Cortona is derived from Latin Cortōna, and from Etruscan 𐌂𐌖𐌓� ...

.

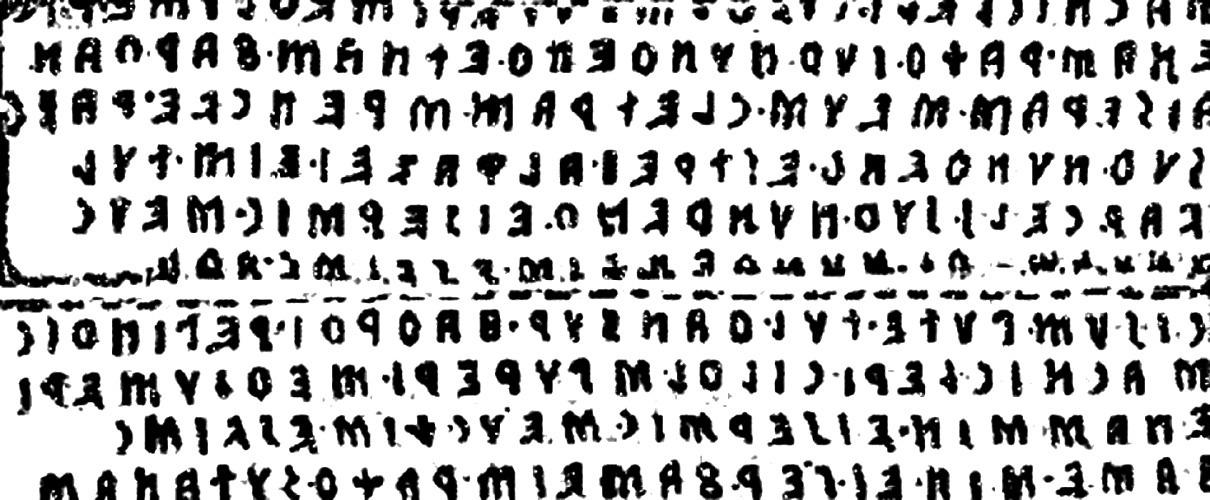

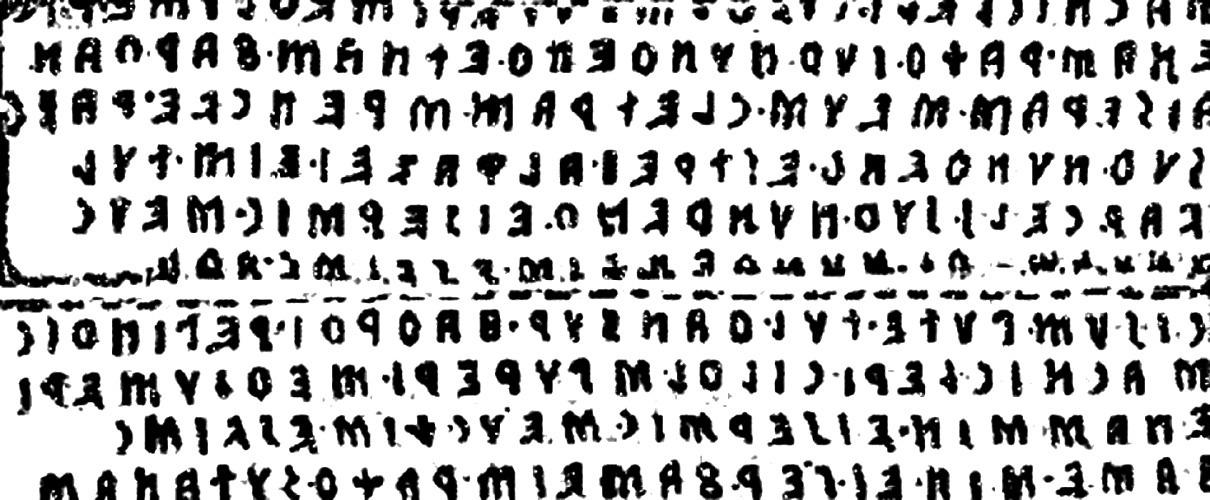

Structure

The book is laid out in twelve columns from right to left, each one representing a "page". Much of the first three columns is missing, and it is not known where the book begins. Closer to the end of the book the text is almost complete (there is a strip missing that runs the entire length of the book). By the end of the last page the cloth is blank and theselvage

A selvage (US English) or selvedge (British English) is a "self-finished" edge of a piece of fabric which keeps it from unraveling and fraying. The term "self-finished" means that the edge does not require additional finishing work, such as hem ...

is intact, showing the definite end of the book.

There are 230 lines of text, with 1330 legible words, but only about 500 distinct words or roots. Only about 60% of the text is thought to have been preserved. Black ink has been used for the main text, and red ink for lines and diacritic

A diacritic (also diacritical mark, diacritical point, diacritical sign, or accent) is a glyph added to a letter or to a basic glyph. The term derives from the Ancient Greek (, "distinguishing"), from (, "to distinguish"). The word ''diacriti ...

s.

In use, it would have been folded so that one page lay on top of another like a codex

The codex (plural codices ) was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term ''codex'' is often used for ancient manuscript books, with ...

, rather than being wound along like a scroll

A scroll (from the Old French ''escroe'' or ''escroue''), also known as a roll, is a roll of papyrus, parchment, or paper containing writing.

Structure

A scroll is usually partitioned into pages, which are sometimes separate sheets of papyrus ...

. Julius Caesar is said to have folded scrolls in similar accordion

Accordions (from 19th-century German ''Akkordeon'', from ''Akkord''—"musical chord, concord of sounds") are a family of box-shaped musical instruments of the bellows-driven free-reed aerophone type (producing sound as air flows past a reed ...

fashion while on campaigns.

Content

Though the Etruscan language is not fully understood, many words and phrases can be deciphered, enough to give us an indication of the subject matter. Both dates and the names of gods are found throughout the text, giving the impression that the book is a religious calendar. Such calendars are known from the Roman world, giving not only the dates of ceremonies and processions, but also the rituals and liturgies involved. The lost are referred to by several Roman antiquarians. The theory that this is a religious text is strengthened by recurring words and phrases that are surmised to have liturgical or dedicatory meanings. Some notable formulae on the Liber Linteus include a hymn-like repetition of in column 7, and variations on the phrase , which is translated by van der Meer as "by the sacred fraternity/priesthood of , and by the of ". Though many of the specific details of the rituals are unclear, they seem to have been performed outside cities, sometimes near specific rivers, sometimes on (or at least for) hilltops/citadels, sometimes apparently in cemeteries. Based on the two unambiguous dates that survive — June 18 in 6.14 and September 24 in 8.2 — it is supposed that roughly columns 1-5 deal with rituals occurring in the months before June (probably starting in March, and perhaps there was introductory or other material here as well), column 6 with June rituals, column 7 may refer to rituals in July and possibly August, column 8 September rituals, and 9-12 concerning rites to be performed from October through February. Other numbers are mentioned which are probably also dates, but as the months aren't indicated, we cannot be sure where exactly they fall in the year.L. B. van der Meer Liber linteus zagrabiensis. The Linen Book of Zagreb. A Comment on the Longest Etruscan Text. Louvain/Dudley, MA 2007 pp. 28-43 et passim Throughout this calendar there is also a fairly clear progression of which kinds of deities are to be propitiated in which months and seasons. Only two individual gods are set off by being preceded by the term ''farθan fleres'', probably "the Genius (or Father?) of the spirit of/in..." These are ''Crap-'' and '' Neθuns'', the first probably equivalent to ''Tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

'', the Etruscan Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

, and the second roughly equivalent to Latin Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 times ...

. It is notable that ''Crap-''/Jupiter is mentioned in the first half of the text (in columns 3, 4, and 6), that is, up to June (specifically before the summer solstice

The summer solstice, also called the estival solstice or midsummer, occurs when one of Earth's poles has its maximum tilt toward the Sun. It happens twice yearly, once in each hemisphere ( Northern and Southern). For that hemisphere, the summer ...

on June 21), but he is not ever mentioned later in the calendar (as far as we can see in the text that is legible). On the other hand, ''Neθuns''/Neptune does not occur (again, as far as we can see) in these earlier passages/months/seasons, but only after the vernal equinox Spring equinox or vernal equinox or variations may refer to:

* March equinox, the spring equinox in the Northern Hemisphere

* September equinox, the spring equinox in the Southern Hemisphere

Other uses

* Nowruz, Persian/Iranian new year which be ...

on September 21 (specifically just after September 24, mentioned in 8.3, then also 8.11, 9.18 and 9.22). Similarly, on the one hand, other deities of light, such as '' θesan'' "Dawn" and ''Lusa'' are only mentioned in the earlier part of the calendar: ''θesan'' at 5.19-20 ''θesan tini θesan eiseraś śeuś'' probably "Dawn of (bright) Jupiter (and) Dawn of the Dark Deities," (probably referring to Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

as morning and evening star) and ''Lusa'' at 6.9; while, on the other hand, various terms thought or known to refer to specifically underworld deities exclusively appear later in the calendar: '' Satrs'' "Saturn/Cronos" (11.f4), '' Caθ-'' (in columns 10 and 12), ''Ceu-'' (at 7.8), '' Velθa'' (7, 10, and 11), and ''Veive-/Vetis'' = Latin '' Veiovis/Vedius,'' (described by van der Meer as an "underworld Jupiter") in 10 and 11. But some the apparent underworld deities, such as ''Zer'', show up in both halves (4, 5, 9), while ''Lur'', also thought to be chthonic

The word chthonic (), or chthonian, is derived from the Ancient Greek word ''χθών, "khthon"'', meaning earth or soil. It translates more directly from χθόνιος or "in, under, or beneath the earth" which can be differentiated from Γῆ ...

, only appears in columns 5 and 6. van der Meer claims that many of the locations in the year of these deities' rituals correspond to the same deities' locations on the Liver of Piacenza and in other Etruscan sources that hint at how they divided the heavens or the divine realm. On the other hand, Belfiore considers ''Crap'' to be an underworld deity.

There are a variety of types of ritual (the general term for which seems to be ''eis-na/ ais-na'' literally "for the gods, divine (act)") described in the text. The most frequently mentioned include ''vacl'', probably "libation", usually of ''vinum'' "wine" (sometimes specifically "new wine") but also of oil ''faś'' and other liquids whose identities are unclear; ''nunθen'' "invoke" or possibly "offer (with an invokation)"; ''θez-'' probably "sacrifice" but possibly "to present" sacrifice(s) or offering(s) (''fler(χva)'') often of ''zusle(va)'' "piglet(s)" (or perhaps some other animal). Offerings and sacrifices were placed: on the right and/or left ''hamΦeś leiveś'' (and variations thereof); on fire ''raχθ''; on a stone (altar?) ''luθt(i)''; on the ground ''cel-i''; or with/on a decorated (?) litter ''cletram śrenχve'' among others. They were often performed three times ''ci-s-um/ci-z'' and often happened or were concluded during the morning ''cla θesan'' (a term that seems to mark the end of rituals in this text, since blank lines follow it, followed by a new (partial or complete) date). Column 7 (July and/or August?) may be devoted to describing a series of funereal rites connected to the Adonia festival ritually mourning the death of Aphrodite

Aphrodite ( ; grc-gre, Ἀφροδίτη, Aphrodítē; , , ) is an ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, and procreation. She was syncretized with the Roman goddess . Aphrodite's major symbols include ...

's lover Adonis. A variety of types of priest ''cepen'' (but notably not civil authorities) are mentioned, but the exact distinctions between them are not completely clear: ''tutin'' "of the village"(?); ''ceren'', ''θaurχ'' both "of the tomb"; ''cilθ-l/cva'' "of the citadel(s)/hiltop(s)". Less clear are the kinds of priest indicated by the following (if they refer to priests at all): ''zec, zac, sve, θe, cluctra, flanaχ, χuru'' ("arch-"?), ''snuiuΦ'' ("permanent"?), ''cnticn-'' ('"ad hoc"?), ''truθur'' ("omen interpreter from lightening"?), ''peθereni'' ("of the god Peθan"?), ''saucsaθ'' ( riestor oly areaof the god Saucne") at 3.15. If the last equation is correct it could point to a connection between Liber Linteus and the second longest Etruscan text which happens to also be a ritual calendar, the Tabula Capuana

The ''Tabula Capuana'' ("Tablet from Capua"; Ital. ''Tavola Capuana''), is an ancient terracotta slab, , with a long inscribed text in Etruscan, dated to about 470 bce, apparently a ritual calendar. About 390 words are legible, making it the se ...

(line 2), since the root ''sauc-'' seems to occur in both in a part of each text that probably corresponds to March (though that month is not directly named in any obvious way in either text).

Short sample of the text and partial translation

Column 3, strip C (There are no punctuation marks in the original beyond interpuncts between most words. Those provided here are to make it easier to match the original with the translation.) ::12 lr, etnam tesim, etnam c lucn ::13 cletram śren-χve. trin: θezi-ne χim fler ::14 tar-c. mutin um anancveś; nac cal tar-c ::15 θezi. vacl an ścanin-ce saucsaθ . persin ::16 cletram śrenχve iχ ścanin-ce. clz vacl ::17 ar-a. nunθene śaθ-aś, naχve heχz, male. A tentative partial translation: "The sacrifice, be it funerary, rbe it chthonic s to be puton the decorated litter.hen

Hen commonly refers to a female animal: a female chicken, other gallinaceous bird, any type of bird in general, or a lobster. It is also a slang term for a woman.

Hen or Hens may also refer to:

Places Norway

*Hen, Buskerud, a village in Ringer ...

say: 'The sacrifice and the dog(?) are presented as the offering.' And collect the goblets; and then present the puppy(?) and the dog(?). The libation that was poured in the acred areaof ''Saucne Persi'' hould be pouredjust as it was poured on the decorated litter. Make the libation three times. Make the offering s it has beenestablished, carry tout as is appropriate, ndobserve he appropriate rituals?)."

Note: The last word, ''male'' is related to the well-attested Etruscan words for "mirror": ''mal(e)na'' and ''malstria''.

Notes

Bibliography

* * Olzscha, K. (1934) "Aufbau und Gliederung in den Parallelstellen der Agramer Mumienbinden" I and II in ''Studi Etruschi'' VIII pp. 247 ff. and IX 1935 pp. 191 ff. * Runes, M. and S. P. Corsten (1935) ''Der etruskische Text der Agramer Mumienbinden. Mit einem Glossar von S. P. Corsen'' Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht ("Forschungen zur griechischen und lateinischen Grammatik" volume 11). * Olzscha, K. (1939) "Interpretation der Agramer Mumienbinden" in ''Klio'' Beiheft 40 Leipzig. * * Pfiffig, A. J. (1963) "Studien zu den Agramer Mumienbinden" in ''Denkschriften der Österreichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, philosophisch-historische Klasse'' Bd. 81 Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Wien. * Fowler, M and R. G. Wolfe (preparers) (1965) ''Materials for the Study of the Etruscan Language'' University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 108-11* Roncalli, F. (1978-1980) "Osservazioni sui ''libri lintei'' etruschi" in ''Rendiconti. Pontificia Accademia'' 51-52 982 pp. 3-21. * Rix, H. (1985) "Il ''liber linteus'' di Zagabria" in ''Scrivere etrusco'' pp. 17-52. * Pallottino, M. (1986) "Il libro etrusco della uimmia di Zagabria. Significato e valore storico e linguistico del documento" in ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 19, pp. 1-5. * Pfiffig, A. J. (1986) "Zur Heuristik des ''Liber linteus zagrabiensis''" ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 19, pp. 9–13. * Flury-Lemberg, M. (1986) "Die Rekonstruktion des ''liber linteus Zagrabiensis'' oder die Mumienbinden von Zagreb," ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 19, pp. 73–79 * Mirnik, I., Rendić-Miočević, A. (1996) "Liber linteus Zagrbiensis I" ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 19, pp. 41–71. * Mirnik, I., Rendić-Miočević, A. (1997) "Liber linteus Zagrbiensis II" ''Vjesnik Arheološkog Muzeja u Zagrebu'' 20, pp. 31–48. * Rix, H. (1991) ''Etruskische Texte: Editio minor.'' I-II, Tübingen. * Steinbauer, D.H. (1999) ''Neues Handbuch des Etruskischen'' (Studia Classica, Band 1) St. Katharinen. * * van der Meer, L. B. (2007) ''Liber linteus zagrabiensis. The Linen Book of Zagreb. A Comment on the Longest Etruscan Text''. Louvain/Dudley, MA . * * Belfiore, V. (2010) ''Il liber linteus di Zagabria: testualità e contenuto''. Biblioteca di ''Studi Etruschi'' 50 Pisa-Roma. . * van der Meer, L. B. (2011) Review of V. Belfiore's ''Il liber linteus di Zagabria'' (2010) in ''Bryn Mawr Classical Review'' 1.3

* Meiser, G. (2012) "Umbrische Kulte im Liber Linteus?", in ''Kulte, Riten, religise Vorstellung bei den Etruskern, a cura di P.Amman'', Wien, 163-172

* Woudhuizen, F. C. (2013) ''The Liber linteus: A Word for Word Commentary to and Translation of the Longest Etruscan Text. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft, Neue Folge, Bd 5.'' Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen der Universität Innsbruck Bereich Sprachwissenschaft. ISBN 9783851242317. * Tikkanen, K. W. (2014) Review of Woudhuizen, F. C. (2013) in ''Bryn Mawr Classical Review'' 11.1

* Dupraz, E. (2019) ''Tables Eugubines ombriennes et Livre de lin étrusque: Pour une reprise de la comparaison'' Herman: Paris .

External links

* {{Etruscans 3rd-century BC manuscripts 1867 archaeological discoveries Etruscan artefacts Etruscan inscriptions Archaeology of Croatia Tourism in Zagreb