Lewis Stucley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Lewis Stucley (1574–1620)

Sir Lewis Stucley (1574–1620)

There were in fact two published documents in which Stucley put his side of the argument, an ''Apology'', and the ''Petition'' of 26 November. There was also an official defence of the king's proceedings, the ''Declaration'', written by

There were in fact two published documents in which Stucley put his side of the argument, an ''Apology'', and the ''Petition'' of 26 November. There was also an official defence of the king's proceedings, the ''Declaration'', written by

Devon Perspectives page

;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Stucley, Lewis Year of birth missing 1620 deaths 17th-century English people

Sir Lewis Stucley (1574–1620)

Sir Lewis Stucley (1574–1620) lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or ar ...

of the manor of Affeton in Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

, was Vice-Admiral of Devonshire

The holder of the post Vice-Admiral of Devon was responsible for the defence of the Devon, county of Devon, England.

History

As a Vice-Admiral, the post holder was the chief of naval administration for his district. His responsibilities include ...

. He was guardian of Thomas Rolfe

Thomas Rolfe (January 30, 1615 – ) was the only child of Matoaka (Pocahontas) and her English husband, John Rolfe. His maternal grandfather was Chief Wahunsenacawh (or Powhatan), the leader of the Powhatan tribe in Virginia.

Early life

Thomas ...

, and a main opponent of Sir Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh (; – 29 October 1618) was an English statesman, soldier, writer and explorer. One of the most notable figures of the Elizabethan era, he played a leading part in English colonisation of North America, suppressed rebellion ...

in his last days. Stucley's reputation is equivocal; popular opinion at the time idealised Raleigh, and to the public he was Sir "Judas" Stucley.

Origins

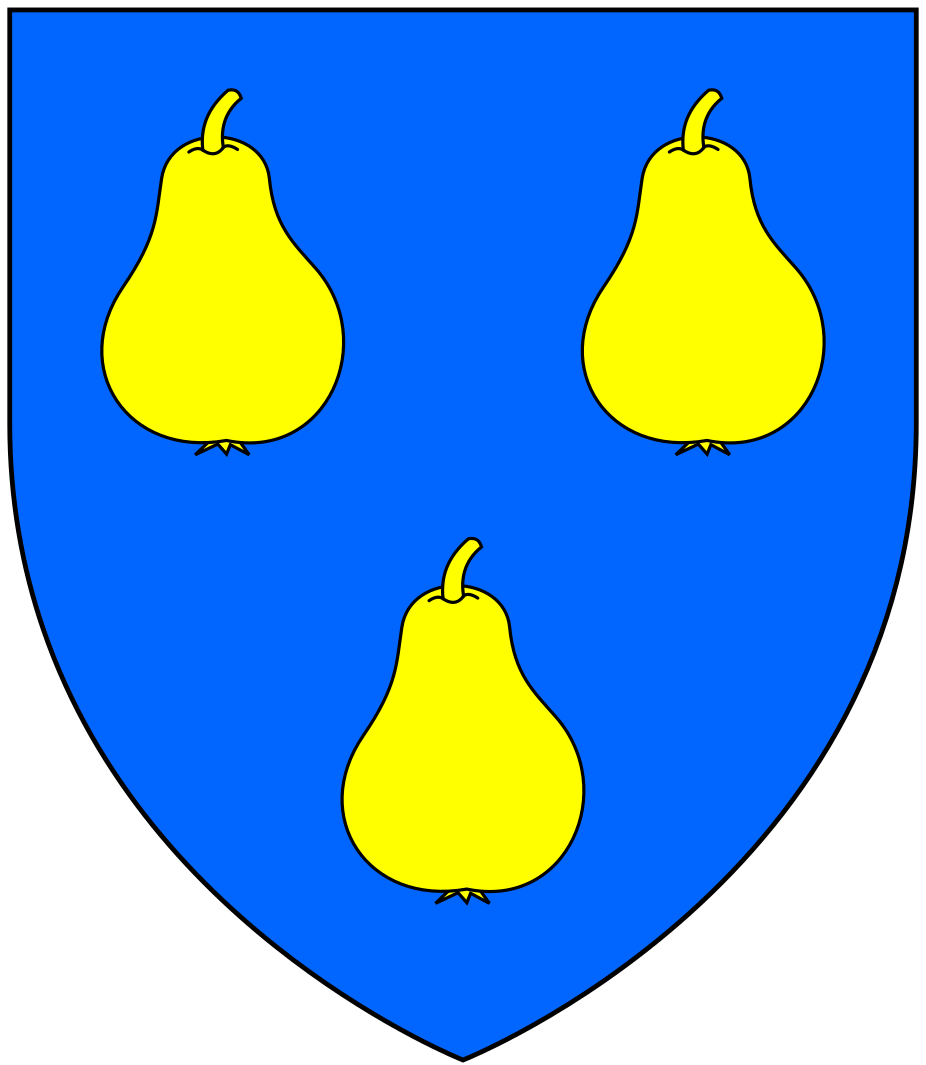

He was the eldest son of John Stucley (1551-1611)lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or ar ...

of the manor of Affeton in Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

, and his wife Frances St Leger, daughter of Sir John St Leger, (d.1596) of Annery in Devon, His grandfather Lewis Stucley (c.1530–1581) of Affeton was the eldest brother of Thomas Stucley

Thomas Stucley (c. 15254 August 1578), also written Stukeley or Stukley and known as the Lusty Stucley,Vivian 1895, p. 721, pedigree of Stucley was an English mercenary who fought in France, Ireland, and at the Battle of Lepanto (1571) and ...

(1520–1578) ''The Lusty Stucley'', a mercenary

A mercenary, sometimes also known as a soldier of fortune or hired gun, is a private individual, particularly a soldier, that joins a military conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any o ...

leader who was killed fighting against the Moors at the Battle of Alcazar

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force ...

.

Career

The younger Lewis was knighted by KingJames I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

when on his way to London in 1603. In April 1617 he was appointed guardian of Thomas Rolfe, the two-year-old son of John Rolfe

John Rolfe (1585 – March 1622) was one of the early English settlers of North America. He is credited with the first successful cultivation of tobacco as an export crop in the Colony of Virginia in 1611.

Biography

John Rolfe is believed ...

and Rebecca (Pocahontas

Pocahontas (, ; born Amonute, known as Matoaka, 1596 – March 1617) was a Native American woman, belonging to the Powhatan people, notable for her association with the colonial settlement at Jamestown, Virginia. She was the daughter of ...

). He later transferred Thomas's wardship to John's brother, Henry Rolfe in Heacham

Heacham is a large village in West Norfolk, England, overlooking The Wash. It lies between King's Lynn, to the south, and Hunstanton, about to the north. It has been a seaside resort for over a century and a half.

History

There is evidence o ...

.

The Raleigh arrest

Stucley purchased the office of vice-admiral in 1618, and very soon became embroiled in high politics. In June 1618 he left London with verbal orders from the king to deal with the imminent difficulty with Sir Walter Raleigh, when he arrived atPlymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

on his return from the 1617 Orinoco

The Orinoco () is one of the longest rivers in South America at . Its drainage basin, sometimes known as the Orinoquia, covers , with 76.3 percent of it in Venezuela and the remainder in Colombia. It is the fourth largest river in the wor ...

expedition. As had been recognised by a royal proclamation of 9 June, Raleigh had broken the peace treaty between England and Spain. There was intense diplomatic embarrassment for King James in the situation; Stucley may have understood the king's intention to be that Raleigh should flee the country, but in any case his approach was relaxed for a number of weeks.

Stucley had a public notary board Raleigh's ship the ''Destiny'' in port. Then on the basis of a letter from the Lord High Admiral, Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham

Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham, 2nd Baron Howard of Effingham, KG (1536 – 14 December 1624), known as Lord Howard of Effingham, was an English statesman and Lord High Admiral under Elizabeth I and James I. He was commander of the Eng ...

, dated 12 June, Stucley had the written authority to arrest Raleigh. He met Raleigh at Ashburton, and accompanied him back to Plymouth. While Stucley was waiting for further orders, Raleigh attempted to escape to France; but returned to his arrest. Stucley sold off the ''Destinys cargo of tobacco.

Stucley had been told to make the journey easy for Raleigh, and show respect for his poor health. Setting off in earnest from the Plymouth area, from John Drake's house some way to the east and joining the Fosse Way

The Fosse Way was a Roman road built in Britain during the first and second centuries AD that linked Isca Dumnoniorum (Exeter) in the southwest and Lindum Colonia (Lincoln) to the northeast, via Lindinis (Ilchester), Aquae Sulis ( Bath), Corini ...

near Musbury

Musbury is a village and civil parish in the East Devon district of Devon, England. It lies approximately away from Colyton and away from Axminster, the nearest towns. Musbury is served by the A358 road and lies on the route of the East Devo ...

, on 25 July, Stucley's party escorted Raleigh. The events that followed were later much discussed. Raleigh traveled with his wife and son. One of Stucley's entourage was a French physician, Guillaume Manoury. They went via Sherborne

Sherborne is a market town and civil parish in north west Dorset, in South West England. It is sited on the River Yeo, on the edge of the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. The parish includes the hamlets of Nether Coombe and Lower Clatcombe. T ...

, met Sir John Digby

John Digby, 1st Earl of Bristol (February 1580 – 21 January 1653),David L. Smith, 'Digby, John, first earl of Bristol (1580–1653)’, ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008. was an E ...

, and stayed with Edward Parham at Poyntington

Poyntington is a village and civil parish in the county of Dorset in South West England. It lies on the edge of the Blackmore Vale about north of Sherborne. In the 2011 census the parish had a population of 128.

Poyntington shares a grouped pa ...

. They reached Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

on the 27th, haste now prompted by an official reproach.

At Salisbury the journey halted for a time. Manoury connived at a sickness Raleigh alleged, and Raleigh used the break in the journey to prepare some defense. The king was there, on a summer progress, and Raleigh used several devices to play for time, composing a state paper in justification of his expedition. A. L. Rowse, ''Ralegh and the Throckmortons'' (1962), p. 313. At this point Stucley refused a bribe which Raleigh offered him. On 1 August they moved on.

With Raleigh in London

By the time the party reachedAndover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

* Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Ando ...

, Stucley was aware that Raleigh intended to escape, and kept a better guard on him. He also countered Raleigh's attempts to corrupt him with duplicity, pretending to be swayed. In London on 7 August, Raleigh was for a short time a prisoner at large, lodging at his wife's house in Broad Street; he used the excuse of illness to argue for this lenient treatment, and was granted five days to regain his health. A chance contact in a Brentford inn with a French official gave him hope.

Raleigh attempted an escape down the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

, on 9 August; it was with the help of Stucley, who intended to betray him. The plot to ensnare Raleigh involved William Herbert, who had accompanied the Raleigh expedition, and others, as well as Stucley. Raleigh with a party including Stucley took a wherry

A wherry is a type of boat that was traditionally used for carrying cargo or passengers on rivers and canals in England, and is particularly associated with the River Thames and the River Cam. They were also used on the Broadland rivers of No ...

at night from Towers Stairs; they got past Woolwich

Woolwich () is a district in southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was maintained throu ...

, but around Gallions Reach

Gallions Reach is a stretch of the River Thames between Woolwich and Thamesmead. The area is named for the Galyons, a 14th-century family who owned property along this stretch of the river,Hidden London http://hidden-london.com/gazetteer/ga ...

were overhauled by a larger wherry, carrying Herbert. They returned to Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

, and Stucley arrested Raleigh once more in the name of the king.

Raleigh's end and Stucley's disgrace

After the attempt, Raleigh was placed in theTower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

. He was executed on 29 October, on the old high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

charged related to the 1603 Main Plot

The Main Plot was an alleged conspiracy of July 1603 by English courtiers to remove King James I from the English throne and to replace him with his cousin Lady Arbella Stuart. The plot was supposedly led by Lord Cobham and funded by the Spanis ...

; more recent testimony was not legally employed. On the scaffold Raleigh made his last speech, making a point of naming Stucley (to say he was forgiven).

Stucley had given hostile, but not necessarily false, evidence against Raleigh. A public furore arose. It appeared that Stucley, wrongly said to be Raleigh's cousin, was appointed his warden not only as the vice-admiral of Devonshire, but as having an old grudge against Raleigh dating from 1584, when Raleigh deceived his father, John, then a volunteer in Sir Richard Grenville

Sir Richard Grenville (15 June 1542 – 10 September 1591), also spelt Greynvile, Greeneville, and Greenfield, was an English privateer and explorer. Grenville was lord of the manors of Stowe, Cornwall and Bideford, Devon. He subsequently ...

's Virginia voyage. It was alleged, and officially denied, that Stucley wished to let Raleigh escape in order to gain credit for rearresting him.

The Earl of Nottingham threatened to cudgel Stucley. The king said "On my soul, if I should hang all that speak ill of thee, all the trees in the country would not suffice".

Pamphlets

Raleigh had an effective posthumous advocate inRobert Tounson

Robert Tounson (1575 – 15 May 1621) — also seen as “Townson” and “Toulson” — was Dean of Westminster from 1617 to 1620, and later Bishop of Salisbury from 1620 to 1621. He attended Sir Walter Raleigh at his execution, and wrote aft ...

, who had attended his last days. While saying on the scaffold that he forgave everyone, having taken the sacrament for the last time, Raleigh still called Stucley perfidious. Stucley put together a defence of his own actions, for which Leonell Sharpe may have been the writer.Lisa Jardine

Lisa Anne Jardine (née Bronowski; 12 April 1944 – 25 October 2015) was a British historian of the early modern period.

From 1990 to 2011, she was Centenary Professor of Renaissance Studies and Director of the Centre for Editing Lives and ...

and Alan Stewart, ''Hostage to Fortune: The troubled life of Francis Bacon 1561–1626'' (1998), p. 424.

There were in fact two published documents in which Stucley put his side of the argument, an ''Apology'', and the ''Petition'' of 26 November. There was also an official defence of the king's proceedings, the ''Declaration'', written by

There were in fact two published documents in which Stucley put his side of the argument, an ''Apology'', and the ''Petition'' of 26 November. There was also an official defence of the king's proceedings, the ''Declaration'', written by Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, possibly with Henry Yelverton and Robert Naunton

Sir Robert Naunton (1563 – 27 March 1635) was an English writer and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1606 and 1626.

Family

Robert Naunton was the son of Henry Naunton of Alderton, Suffolk, and Elizabeth Ashe ...

. The ''Apology'' having failed, Stucley issued the ''Petition'' in effect asking for official backing; which was published in the ''Declaration'' of 27 November, the printers having been up all night.

Aftermath and death

John Chamberlain wrote to Sir Dudley Carleton at the end of 1618, reporting Stucley's reputation as a betrayer, and reporting the "Judas" epithet. In January 1619 Stucley and his son were charged with clipping coin, on slender evidence from a servant who had formerly been employed as a spy on Raleigh. The coins were £500 in gold, a payment for his expenses in dealing with Raleigh, and regarded asblood money

Blood money may refer to:

* Blood money (restitution), money paid to the family of a murder victim

Films

* Blood Money (1917 film), ''Blood Money'' (1917 film), a film starring Harry Carey

* Blood Money (1921 film), ''Blood Money'' (1921 film ...

as reported by Thomas Lorkyn writing to Sir Thomas Puckering in early 1619 (N.S.). It has been suggested by Baldwin Maxwell that the character of Septimius in ''The False One

''The False One'' is a late Jacobean stage play by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, though formerly placed in the Beaumont and Fletcher canon. It was first published in the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647.

This classical history ...

'' was a contemporary reference to Stucley; though this hypothesis has been regarded as unprovable.

The king pardoned him; but popular hatred pursued him to Affeton, and he fled to the island of Lundy, where he died in the course of 1620, raving mad it was rumoured.

Family

In 1596 he married Frances Monck (born 1571), eldest daughter of Anthony Monck who lived atPotheridge

Potheridge (''alias'' Great Potheridge, Poderigge, Poderidge or Powdrich) is a former Domesday Book estate in the parish of Merton, in the historic hundred of Shebbear, 3 miles south-east of Great Torrington, Devon, England. It is the site ...

in Devon and aunt of George Monck

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cruc ...

, 1st Duke of Albemarle, having six sons and one daughter. From the point of view of Stucley's reputation at the time, it mattered whether Raleigh was part of his extended family

An extended family is a family that extends beyond the nuclear family of parents and their children to include aunts, uncles, grandparents, cousins or other relatives, all living nearby or in the same household. Particular forms include the stem ...

, which was widely believed, but they were not related.

References

External links

* s:Devonshire Characters and Strange Events/Sir "Judas" Stukeley bySabine Baring-Gould

Sabine Baring-Gould ( ; 28 January 1834 – 2 January 1924) of Lew Trenchard in Devon, England, was an Anglican priest, hagiographer, antiquarian, novelist, folk song collector and eclectic scholar. His bibliography consists of more than 1,240 ...

Devon Perspectives page

;Attribution {{DEFAULTSORT:Stucley, Lewis Year of birth missing 1620 deaths 17th-century English people

Lewis

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* "Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohead ...