Leo Chiozza Money on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

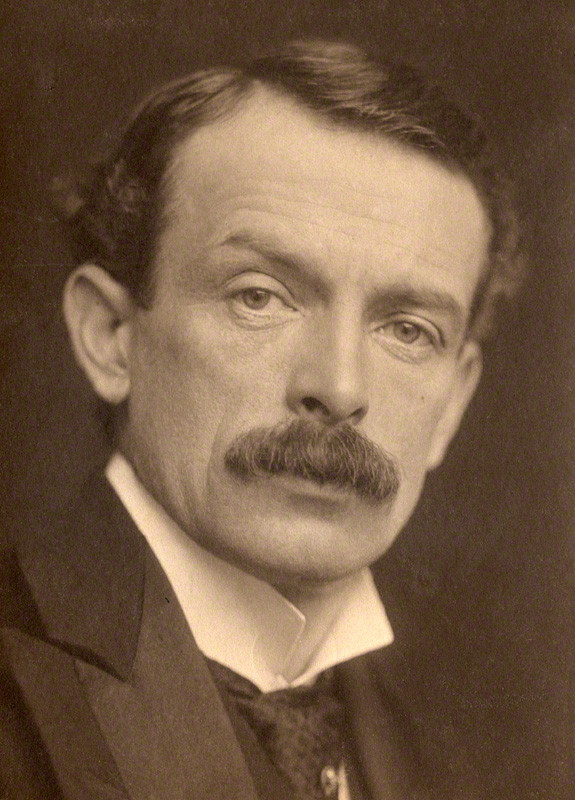

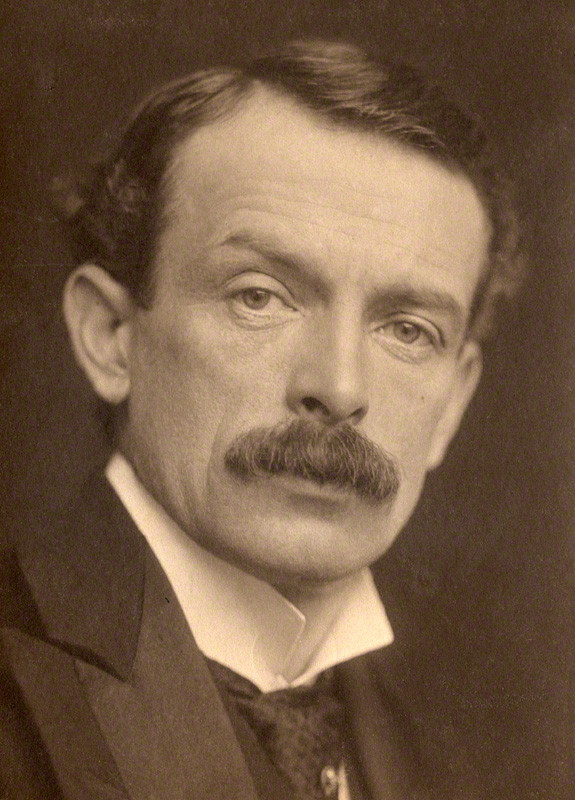

Sir Leo George Chiozza Money (; 13 June 1870 – 25 September 1944), born Leone Giorgio Chiozza, was an Italian-born economic theorist who moved to Britain in the 1890s, where he made his name as a politician, journalist and author. In the early years of the 20th century his views attracted the interest of two future Prime Ministers,

Sir Leo George Chiozza Money (; 13 June 1870 – 25 September 1944), born Leone Giorgio Chiozza, was an Italian-born economic theorist who moved to Britain in the 1890s, where he made his name as a politician, journalist and author. In the early years of the 20th century his views attracted the interest of two future Prime Ministers,

Sir Leo George Chiozza Money (; 13 June 1870 – 25 September 1944), born Leone Giorgio Chiozza, was an Italian-born economic theorist who moved to Britain in the 1890s, where he made his name as a politician, journalist and author. In the early years of the 20th century his views attracted the interest of two future Prime Ministers,

Sir Leo George Chiozza Money (; 13 June 1870 – 25 September 1944), born Leone Giorgio Chiozza, was an Italian-born economic theorist who moved to Britain in the 1890s, where he made his name as a politician, journalist and author. In the early years of the 20th century his views attracted the interest of two future Prime Ministers, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

and Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. After a spell as Lloyd George's parliamentary private secretary

A Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) is a Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom who acts as an unpaid assistant to a minister or shadow minister. They are selected from backbench MPs as the 'eyes and ears' of the minister in the H ...

, he was a Government minister in the latter stages of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. In later life the police's handling of a case in which he and factory worker Irene Savidge were acquitted of indecent behaviour aroused much political and public interest. A few years later he was convicted of an offence involving another woman.

Background and early career

Money was born inGenoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

, Italy. His father was Anglo-Italian and his mother English. He was educated privately and, in 1903, largely anglicised

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influen ...

his name, appending "Money" for what Lloyd George's biographer John Grigg

John Edward Poynder Grigg (15 April 1924 – 31 December 2001) was a British writer, historian and politician. He was the 2nd Baron Altrincham from 1955 until he disclaimed that title under the Peerage Act on the day it received Royal Assen ...

has described as "eponymous

An eponym is a person, a place, or a thing after whom or which someone or something is, or is believed to be, named. The adjectives which are derived from the word eponym include ''eponymous'' and ''eponymic''.

Usage of the word

The term ''epon ...

reasons". He and his English wife Gwendoline had a daughter, Gwendoline Doris, born in 1896.

Economic publications

In London, Money established himself as a journalist, becoming especially noted for his use of statistical analysis. He has sometimes been referred to as a " New Liberal" economist. From 1898 to 1902 he was managing editor of Henry Sell's ''Commercial Intelligence'', a journal devoted to the cause offree trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

, which Money further championed in his books ''British Trade and the Zollverein

The (), or German Customs Union, was a coalition of German states formed to manage tariffs and economic policies within their territories. Organized by the 1833 treaties, it formally started on 1 January 1834. However, its foundations had b ...

Issue'' (July 1902) and ''Elements of the Fiscal Problem'' (1903). These were timely given the increasingly fervent political and public debate about Imperial Preference

Imperial Preference was a system of mutual tariff reduction enacted throughout the British Empire following the Ottawa Conference of 1932. As Commonwealth Preference, the proposal was later revived in regard to the members of the Commonwealth of N ...

, a cause which led Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

to resign from Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative Party (UK), Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As F ...

's Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

government in 1903. Money argued that, although nobody was proposing a true "British Zollverein or Imperial Customs Union ... an imperial nation like ours cannot afford to benefit the colonies by giving a tariff preference to their products, for ... they cannot supply them in sufficient quantities to support our industries and people". His thinking appears to have had some influence on Winston Churchill, then a Conservative Member of Parliament (MP), who crossed to the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

in 1904 ostensibly because of his Free Trade principles; however, in later correspondence with Money, Churchill probably overstated the extent of his influence. Even so, Churchill told Money plainly in 1914 that he was "a master of efficient statistics and no one states a case with more originality or force"

''Riches and Poverty'' (1905)

In 1905 Money published the work for which he became most noted, ''Riches and Poverty''. This analysis of the distribution of wealth in the United Kingdom, which he revised in 1912, proved influential and was widely quoted by socialists,Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

politicians and trade unionists. The future Labour Prime Minister, Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, (3 January 18838 October 1967) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was Deputy Prime Mini ...

, whose government from 1945-51 established the modern welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal opportunity, equitabl ...

, recalled that, while he was working at a boys' club at Haileybury, he had spent an evening studying ''Riches and Poverty''. Among other things, Money claimed that 87% of private property was owned by 883,000 people (or 4.4 million if families and dependents were included), while the remaining 13% was shared between 38.6 million. These and other calculations were contested at the time as taking insufficient account of age and family structures, but were frequently cited as the best available figures of their kind. Money sought also to quantify Britain's middle class and its ''per capita'' wealth, calculating that 861,000 people in 1905 and 917,000 in 1912 owned property worth between £500 and £50,000, although, allowing for four dependents per property owner, the ''per capita'' figure was less that £1,000. In general his findings pointed to the modest size of most middle class fortunes in Edwardian

The Edwardian era or Edwardian period of British history spanned the reign of King Edward VII, 1901 to 1910 and is sometimes extended to the start of the First World War. The death of Queen Victoria in January 1901 marked the end of the Victori ...

times, a picture broadly consistent with calculations made by Robert Giffen

Sir Robert Giffen (22 July 1837 – 12 April 1910) was a Scottish statistician and economist.

Life

Giffen was born at Strathaven, Lanarkshire. He entered a solicitor's office in Glasgow, and while in that city attended courses at the uni ...

and Michael Mulhall

Michael Mulhall (born 25 February 1962) is a Canadian prelate of the Roman Catholic Church. Since 2019, he has been the Archbishop of Kingston, Canada. Prior to that, he served the Bishop of Pembroke from 2007 to 2019.

Biography

One of fi ...

in the 1880s (although Money took the view that business wealth was becoming increasingly concentrated in a few hands, whereas, towards the end of the 19th century, Giffen and others, such as Leone Levi

Leone Levi (6 June 1821 – 7 May 1888) was an English jurist and statistician.

Born to a Jewish family in Ancona, Italy, he worked in commerce there before emigrating to Liverpool in 1844. There he obtained British citizenship and joined the Pr ...

, had concluded that such wealth was being spread more widely).

Around this time, Money sometimes shared Fabian platforms with such like-minded thinkers as Sidney Webb

Sidney James Webb, 1st Baron Passfield, (13 July 1859 – 13 October 1947) was a British socialist, economist and reformer, who co-founded the London School of Economics. He was an early member of the Fabian Society in 1884, joining, like Geo ...

and H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

At the 1906 general election, in which the Liberal Party won a landslide victory, Money became Liberal MP for Paddington North. A future Conservative

Lloyd George, who became Chancellor in 1908, valued Money's ability to develop innovative ideas; in 1911 he thanked him specifically for his "magnificent service" in relation to the new

Lloyd George, who became Chancellor in 1908, valued Money's ability to develop innovative ideas; in 1911 he thanked him specifically for his "magnificent service" in relation to the new

On the evening of St. George's Day, 23 April 1928, Money was in Hyde Park with Irene Savidge, a radio valve-tester from

On the evening of St. George's Day, 23 April 1928, Money was in Hyde Park with Irene Savidge, a radio valve-tester from

The Triumph of Nationalization

' (1920)

Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

, F.E. Smith

Frederick Edwin Smith, 1st Earl of Birkenhead, (12 July 1872 – 30 September 1930), known as F. E. Smith, was a British Conservative politician and barrister who attained high office in the early 20th century, in particular as Lord High Chan ...

(later Lord Birkenhead), who also entered Parliament in 1906, poured sarcasm on the Free Trade aspects of Money's campaign (as he did on those of others), claiming that "with an infinitely just appreciation of his own controversial limitations, oney Oney may refer to:

* Oney, France, a subsidiary of French Auchan Holding and Banque Accord

* Oney, Oklahoma, an List of unincorporated communities in Oklahoma, unincorporated community in Oklahoma

* Oney (song), "Oney" (song), a song written by Je ...

relied chiefly on the intermittent exhibition of horse sausages as a witty, graceful and truthful sally at the expense of the great German nation"

Money lost his seat at the January 1910 election, fought principally on the issue of the "People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was bloc ...

" delivered by Lloyd George as Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

in 1909, but in December 1910

The following events occurred in December 1910:

December 1, 1910 (Thursday)

* Porfirio Diaz was inaugurated for his eighth term as President of Mexico."Record of Current Events", ''The American Monthly Review of Reviews'' (January 1911), pp ...

was elected for East Northamptonshire

East Northamptonshire was from 1974 to 2021 a local government district in Northamptonshire, England. Its council was based in Thrapston and Rushden. Other towns include Oundle, Raunds, Irthlingborough and Higham Ferrers. The town of Rushden wa ...

in the second general election of that year. He held that seat until 1918.

Protégé of Lloyd George

Lloyd George, who became Chancellor in 1908, valued Money's ability to develop innovative ideas; in 1911 he thanked him specifically for his "magnificent service" in relation to the new

Lloyd George, who became Chancellor in 1908, valued Money's ability to develop innovative ideas; in 1911 he thanked him specifically for his "magnificent service" in relation to the new national insurance

National Insurance (NI) is a fundamental component of the welfare state in the United Kingdom. It acts as a form of social security, since payment of NI contributions establishes entitlement to certain state benefits for workers and their famil ...

scheme and the following year contributed an introduction to his study of the Act and its purpose, published as ''Insurance Versus Poverty''. In 1912 Money was active also in following up the sinking of the , soliciting from the President of the Board of Trade (Sydney Buxton

Sydney Charles Buxton, 1st Earl Buxton, (25 October 1853 – 15 October 1934) was a radical British Liberal politician of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He also served as the second Governor-General of South Africa from 1914 to 1920

...

) an early breakdown of the number of passengers saved by class and gender. The figures showed, among other things, that, while 63% of first class passengers had survived, only 25% in third class had done so, including a mere 16 of 767 men in third class.

Despite Money's apparent alignment with Lloyd George, he produced various articles early in 1914 that drew attention to reductions in naval expenditure at a time when Germany was increasing such spending. He appears to have received private assistance in this regard from Churchill, who by then had a vested interest as First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

. Churchill offered Money flattering encouragement, while his office supplied him with various statistics (making clear, however, that such data were already available in published documents). In thanking Money for his articles, Churchill added that he was "keeping the proof to encourage the Chancellor 'i.e.'' Lloyd George

When Lloyd George became Minister of Munitions

The Minister of Munitions was a British government position created during the First World War to oversee and co-ordinate the production and distribution of munitions for the war effort. The position was created in response to the Shell Crisis of ...

in 1915, during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, he appointed Money as his parliamentary private secretary

A Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) is a Member of Parliament (MP) in the United Kingdom who acts as an unpaid assistant to a minister or shadow minister. They are selected from backbench MPs as the 'eyes and ears' of the minister in the H ...

(PPS). Money was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed in the same year.

In December 1916 Lloyd George replaced Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of ...

as Prime Minister. Money was initially Parliamentary Secretary (a junior ministerial post) for both pensions and shipping in the re-organised coalition government, although he held the former portfolio for only two weeks, later claiming, rather improbably, that he had "drafted the new Pensions scheme of 1917".

Ministry of Shipping

Money's Minister (or Controller) at the new Ministry of Shipping was Sir Joseph Maclay, a Scottish shipowner who, unusually, sat in neither House of Parliament, as a result of which Money was the ministry's spokesman in theCommons

The commons is the cultural and natural resources accessible to all members of a society, including natural materials such as air, water, and a habitable Earth. These resources are held in common even when owned privately or publicly. Commons ...

(with his own PPS, Thomas Owen Jacobsen

Thomas Owen Jacobsen (23 April 1864 – 15 June 1941) was a British businessman and Liberal politician. He was born in Richmond Terrace, Liverpool, on 23 April 1864, and was the son of a naturalised Dane."Resignation of Mr Neilson", ''The Times ...

). Maclay, who was himself strong willed and very self-disciplined, at first resisted Money's appointment, describing him to Lloyd George as "very clever – but impossible, iving Iving may refer to:

*Intravenous therapy

Intravenous therapy (abbreviated as IV therapy) is a medical technique that administers fluids, medications and nutrients directly into a person's vein. The intravenous route of administration is commonly ...

in an atmosphere of suspicion and distrust of everyone – satisfied only with himself and his own views". However, Lloyd George stuck by the appointment and, in the event, the two men appear to have worked in reasonable harmony. Among Money's particular achievements was developing the policy of concentrating British merchant shipping in the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

, allowing it to be better defended against German U-boats

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare rol ...

and leaving transport of goods around the world to ships of other nationalities. By the time of the Zeebrugge raid

The Zeebrugge Raid ( nl, Aanval op de haven van Zeebrugge;

) on 23 April 1918, was an attempt by the Royal Navy to block the Belgian port of Bruges-Zeebrugge. The British intended to sink obsolete ships in the canal entrance, to prevent German ...

in April 1918, the use of convoys had largely contained the threat from U-boats, with every troopship of American reinforcements over the previous two months having arrived safely.

Labour Party candidate and the Sankey Commission

After the war Money left the Liberal Party forLabour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

, principally over the issues of nationalisation and redistribution of wealth through taxation which, in contrast with most Liberals, he supported. He argued also that substantial investment in organisation and technology would be required to stem economic decline and regretted both the coalition's lack of commitment to free trade and intention to defer Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

for Ireland. Money resigned his government post shortly before the so-called "Coupon" election of 1918, in which, standing as a Labour candidate for South Tottenham

South Tottenham is an area of the London Borough of Haringey, north London.

Location

South Tottenham occupies parts of the N15 and N17 postal districts. It is bordered in the south by Stamford Hill, the west by St Ann's and West Green, the ...

, he lost by 853 votes to the Conservatives' Major Patrick Malone (who, because of local differences over his candidature, had not received the coalition coupon

The Coalition Coupon was a letter sent to parliamentary candidates at the 1918 United Kingdom general election, endorsing them as official representatives of the Coalition Government. The 1918 election took place in the heady atmosphere of victory ...

).

The following year Money was a member of the Royal Commission established under the Coal Industry Commission Act 1919

The Coal Industry Commission Act 1919 (c 1) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom, which set up a commission, led by Mr Justice Sankey (and so known as the "Sankey Commission"), to consider joint management or nationalisation of the coal m ...

and led by Sir John Sankey, that examined the future of the coal-mining industry. He was one of three economists on the commission, all broadly favourable to the miners, the others being Sidney Webb

Sidney James Webb, 1st Baron Passfield, (13 July 1859 – 13 October 1947) was a British socialist, economist and reformer, who co-founded the London School of Economics. He was an early member of the Fabian Society in 1884, joining, like Geo ...

and R. H. Tawney

Richard Henry Tawney (30 November 1880 – 16 January 1962) was an English economic historian, social critic, ethical socialist,Noel W. Thompson. ''Political economy and the Labour Party: the economics of democratic socialism, 1884-2005''. 2nd ...

. Others were appointed from business and the trade unions. No agreement was reached and, when the commission reported in June 1919, it offered four separate approaches ranging from full nationalisation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to pri ...

to untrammelled private ownership. The public impact of the report was such that, in Ben Travers

Ben Travers (12 November 188618 December 1980) was an English writer. His output includes more than 20 plays, 30 screenplays, 5 novels, and 3 volumes of memoirs. He is best remembered for his long-running Aldwych farce, series of farces first ...

' comic novel ''A Cuckoo in the Nest

''A Cuckoo in the Nest'' is a farce by the English playwright Ben Travers. It was first given at the Aldwych Theatre, London, the second in the series of twelve Aldwych farces presented by the actor-manager Tom Walls at the theatre between 1923 ...

'' (1921), the Rev. Cathcart Sloley-Jones, under the illusion that he was addressing a member of parliament, "lowered his voice into a rather sinister whisper: 'What is Lloyd George's real view of the miners' report?'"

Money unsuccessfully fought the Stockport by-election for Labour in a seven-sided contest in 1920.

Later life

Money did not hold ministerial office nor sit in Parliament again after 1918. Therefore, with Lloyd George being forced out as Prime Minister in 1922, his political career was effectively over by the early 1920s. He continued to work as a financial journalist and author, and contributed views in other ways. For example, in 1926 (the year of theGeneral Strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

), he criticised as "utterly humourless" a BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

radio talk in which Father Ronald Knox

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox (17 February 1888 – 24 August 1957) was an Catholic Church in England and Wales, English Catholic priest, Catholic theology, theologian, author, and radio broadcaster. Educated at Eton College, Eton and Balliol Colleg ...

offered an imaginary account of a revolution in Britain that included butchery in St. James's Park

St James's Park is a park in the City of Westminster, central London. It is at the southernmost tip of the St James's area, which was named after a leper hospital dedicated to St James the Less. It is the most easterly of a near-continuous ch ...

, London and the blowing up of the Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank ...

. He also published books of poems.

In his book, ''The Peril of the White'' (1925), Money addressed delicate issues relating to the racial make-up of colonial populations and the implications of a declining white European birth rate for their future governance. He maintained that "the European stock cannot presume to hold magnificent areas indefinitely, even while it refuses to people them, and to deny their use and cultivation to races that sorely need them". He emphasised also that "every ... act ... which denies respect to mankind of whatever race will have to be paid for a hundredfold".

By the mid-1930s, Money appeared to be showing some sympathy for the fascist dictators in Europe, regretting in particular Britain's hostility towards Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

's Italy. Shortly before the Italian invasion of Abyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

in 1935, he corresponded with Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, praising him, among other things, for the measured tone of a speech in which Churchill had maintained that the quarrel with Italy was not one with Britain, but with the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

. During the Second World War Money deplored British bombing of non-military targets in Germany, citing in 1943 Churchill's own denunciation of a "new and odious form of warfare" a few months before becoming Prime Minister in 1940.

However, in terms of their public profile, these various activities paled into insignificance compared to two rather bizarre episodes involving young women that brought Money into contact with the law. In 1928 he was acquitted of indecent behaviour with a woman in London's Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

in a case that became a ''cause célèbre'' and had some influence on future handling by the police of such cases. Then, five years later, he was convicted on a similar charge following an incident in a railway compartment and fined a total of 50 shilling

The shilling is a historical coin, and the name of a unit of modern currencies formerly used in the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, other British Commonwealth countries and Ireland, where they were generally equivalent to 12 pence o ...

s (£2.50).

The Savidge case

On the evening of St. George's Day, 23 April 1928, Money was in Hyde Park with Irene Savidge, a radio valve-tester from

On the evening of St. George's Day, 23 April 1928, Money was in Hyde Park with Irene Savidge, a radio valve-tester from New Southgate

New Southgate is a residential suburb straddling three Outer London Boroughs: a small part of the east of Barnet, a south-west corner of Enfield and in loosest definitions, based on nearest railway stations, a small northern corner of Haringey i ...

in North London. Savidge was engaged to be married. A police constable spotted the exchange of what a later social historian has described as "a rather chaste kiss", but the police said that mutual masturbation was taking place although Money claimed that he had been offering Savidge advice on her career. They were both arrested and charged with indecent behaviour, but the case was dismissed by the Marlborough Street magistrate, who awarded costs of £10 against the police.

At the time of his arrest, Money protested to the police that he was "not the usual riff-raff" but "a man of substance" and, once in custody, was permitted to telephone the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

, Sir William Joynson-Hicks

William is a male given name of Germanic languages, Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norm ...

. The police suspected that his and Savidge's acquittal was an "establishment

Establishment may refer to:

* The Establishment, a dominant group or elite that controls a polity or an organization

* The Establishment (club), a 1960s club in London, England

* The Establishment (Pakistan), political terminology for the military ...

" conspiracy, this leading the Director of Public Prosecutions

The Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) is the office or official charged with the prosecution of criminal offences in several criminal jurisdictions around the world. The title is used mainly in jurisdictions that are or have been members o ...

, Sir Archibald Bodkin

Sir Archibald Henry Bodkin KCB (1 April 1862''London, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538–1812'' – 31 December 1957) was an English lawyer and the Director of Public Prosecutions from 1920 to 1930. He particularl ...

, to authorise them to detain Savidge for further questioning. Her subsequent interrogation, after she had been detained at her place of work, lasted some five hours and was conducted without a female officer being present. Lilian Wyles, one of the officers to collect her, and who expected to be present during the questioning, was told to leave by Chief Inspector Alfred C. Collins, who led the interview. Savidge was required to show the police her pink petticoat

A petticoat or underskirt is an article of clothing, a type of undergarment worn under a skirt or a dress. Its precise meaning varies over centuries and between countries.

According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'', in current British Engl ...

, whose colour and brevity they duly noted and at a certain point Collins caressed her knee.

Savidge complained about her treatment and there followed an adjournment debate in the House of Commons on 17 May 1928, initiated by a Labour MP, Tom Johnston. Joynson-Hicks established a public inquiry

A tribunal of inquiry is an official review of events or actions ordered by a government body. In many common law countries, such as the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, Australia and Canada, such a public inquiry differs from a royal ...

under Sir John Eldon Bankes

Sir John Eldon Bankes, (17 April 1854 – 31 December 1946) was a Welsh judge of the King's Bench Division of the High Court of Justice, and later the Lord Justice of Appeal.

Biography

Born in Northop, Flintshire on 17 April 1854, he was ...

, a retired Lord Justice of Appeal

A Lord Justice of Appeal or Lady Justice of Appeal is a judge of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, the court that hears appeals from the High Court of Justice, the Crown Court and other courts and tribunals. A Lord (or Lady) Justice ...

, which criticised the excessive zeal of the police, but also exonerated Savidge's interrogators of improper conduct. However, the case did lead to reforms in the way that the police dealt with female suspects and enabled a number of public figures to articulate their view that the police should primarily enforce law and order, rather than "trying to be censors of public morals".

Railway incident and conviction

In September 1933 Money was travelling on the Southern Railway betweenDorking

Dorking () is a market town in Surrey in South East England, about south of London. It is in Mole Valley District and the council headquarters are to the east of the centre. The High Street runs roughly east–west, parallel to the Pipp Br ...

and Ewell

Ewell ( , ) is a suburban area with a village centre in the borough of Epsom and Ewell in Surrey, approximately south of central London and northeast of Epsom.

In the 2011 Census, the settlement had a population of 34,872, a majority of wh ...

when, as A.J.P. Taylor

Alan John Percivale Taylor (25 March 1906 – 7 September 1990) was a British historian who specialised in 19th- and 20th-century European diplomacy. Both a journalist and a broadcaster, he became well known to millions through his televis ...

put it in the relevant volume of the ''Oxford History of England'', he "again conversed with a young lady". He was summonsed for taking hold of a shop girl named Ivy Buxton and kissing her face and neck. When Money appeared before Epsom

Epsom is the principal town of the Borough of Epsom and Ewell in Surrey, England, about south of central London. The town is first recorded as ''Ebesham'' in the 10th century and its name probably derives from that of a Saxon landowner. The ...

magistrates on 11 September, he was fined £2 for his behaviour and a further 10 shillings (50p) for interfering with the comfort of other passengers.

Publications

* ''Riches and poverty'' (1905) * ''A Nation Insured'' (1912) *The Triumph of Nationalization

' (1920)

References

Sources

* Daunton, Martin "Money, Sir Leo George Chiozza (1870–1944), politician and author" in ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' * Donaldson, William (2002) ''Brewer's Rogues, Villains & Eccentrics'' * Grigg, John (2001) ''Lloyd George: War Leader 1916–1918'' * Harris, Jose (1993) ''Private Lives, Public Spirit: Britain 1870–1914'' * Pugh, Martin (2008) ''We Danced All Night: A Social History of Britain Between the Wars'' * Taylor, A.J.P. (1965) ''The Oxford History of England: English History 1914–1945'' * Toye, Richard (2007) ''Lloyd George and Churchill'' *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Money, Leo Chiozza 1870 births 1944 deaths Liberal Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Knights Bachelor UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 British politicians of Italian descent Writers from Genoa Labour Party (UK) parliamentary candidates Members of the Fabian Society British politicians convicted of crimes British economists Italian emigrants to the United Kingdom