Le Morte D'Arthur on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

' (originally written as '; inaccurate

Most of the events take place in a

Most of the events take place in a

Prior to Caxton's reorganization, Malory's work originally consisted of eight books:

#The birth and rise of Arthur: "From the Marriage of King Uther unto King Arthur (that reigned after him and did many battles)" (''Fro the Maryage of Kynge Uther unto Kynge Arthure that regned aftir hym and ded many batayles'')

#Arthur's war against the resurgent Western Romans: "The Noble Tale Between King Arthur and Lucius the Emperor of Rome" (''The Noble Tale betwyxt Kynge Arthure and Lucius the Emperour of Rome'')

#The early adventures of Sir Lancelot: "The Noble Tale of Sir Launcelot of the Lake" (''The Noble Tale of Sir Launcelot du Lake'')

#The story of

Prior to Caxton's reorganization, Malory's work originally consisted of eight books:

#The birth and rise of Arthur: "From the Marriage of King Uther unto King Arthur (that reigned after him and did many battles)" (''Fro the Maryage of Kynge Uther unto Kynge Arthure that regned aftir hym and ded many batayles'')

#Arthur's war against the resurgent Western Romans: "The Noble Tale Between King Arthur and Lucius the Emperor of Rome" (''The Noble Tale betwyxt Kynge Arthure and Lucius the Emperour of Rome'')

#The early adventures of Sir Lancelot: "The Noble Tale of Sir Launcelot of the Lake" (''The Noble Tale of Sir Launcelot du Lake'')

#The story of

Arthur is born to the High King of Britain (Malory's "England")

Arthur is born to the High King of Britain (Malory's "England")

Going back to a time before Book II, Malory establishes Sir

Going back to a time before Book II, Malory establishes Sir

The fourth volume primarily deals with the adventures of the young Gareth ("Beaumains") in his long quest for the sibling ladies Lynette and Lyonesse, Lynette and Lioness. The youngest of Arthur's nephews by Morgause and Lot, Gareth hides his identity as a nameless squire at Camelot as to achieve his knighthood in the most honest and honorable way. While this particular story is not directly based on any existing text unlike most of the content of previous volumes, it resembles various Arthurian romances of the Fair Unknown type.

The fourth volume primarily deals with the adventures of the young Gareth ("Beaumains") in his long quest for the sibling ladies Lynette and Lyonesse, Lynette and Lioness. The youngest of Arthur's nephews by Morgause and Lot, Gareth hides his identity as a nameless squire at Camelot as to achieve his knighthood in the most honest and honorable way. While this particular story is not directly based on any existing text unlike most of the content of previous volumes, it resembles various Arthurian romances of the Fair Unknown type.

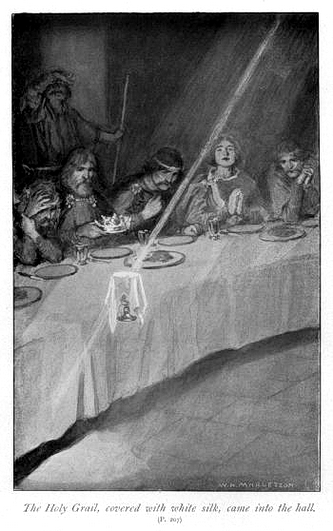

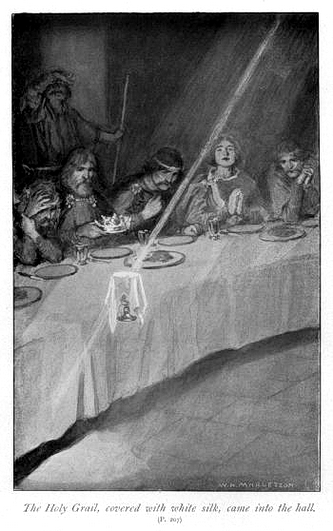

Malory's primary source for this long part was the Lancelot-Grail, Vulgate ''Queste del Saint Graal'', chronicling the adventures of many knights in their spiritual quest to achieve the Holy Grail. Gawain is the first to embark on the quest for the Grail. Other knights like Lancelot, Percival, and Bors the Younger, likewise undergo the quest, eventually achieved by Galahad. Their exploits are intermingled with encounters with maidens and hermits who offer advice and interpret dreams along the way.

After the confusion of the secular moral code he manifested within the previous book, Malory attempts to construct a new mode of chivalry by placing an emphasis on religion. Christianity and the Church offer a venue through which the Pentecostal Oath can be upheld, whereas the strict moral code imposed by religion foreshadows almost certain failure on the part of the knights. For instance, Gawain refuses to do penance for his sins, claiming the tribulations that coexist with knighthood as a sort of secular penance. Likewise, the flawed Lancelot, for all his sincerity, is unable to completely escape his adulterous love of Guinevere, and is thus destined to fail where Galahad will succeed. This coincides with the personification of perfection in the form of Galahad, a virgin wielding the power of God. Galahad's life, uniquely entirely without sin, makes him a model of a holy knight that cannot be emulated through secular chivalry.

Malory's primary source for this long part was the Lancelot-Grail, Vulgate ''Queste del Saint Graal'', chronicling the adventures of many knights in their spiritual quest to achieve the Holy Grail. Gawain is the first to embark on the quest for the Grail. Other knights like Lancelot, Percival, and Bors the Younger, likewise undergo the quest, eventually achieved by Galahad. Their exploits are intermingled with encounters with maidens and hermits who offer advice and interpret dreams along the way.

After the confusion of the secular moral code he manifested within the previous book, Malory attempts to construct a new mode of chivalry by placing an emphasis on religion. Christianity and the Church offer a venue through which the Pentecostal Oath can be upheld, whereas the strict moral code imposed by religion foreshadows almost certain failure on the part of the knights. For instance, Gawain refuses to do penance for his sins, claiming the tribulations that coexist with knighthood as a sort of secular penance. Likewise, the flawed Lancelot, for all his sincerity, is unable to completely escape his adulterous love of Guinevere, and is thus destined to fail where Galahad will succeed. This coincides with the personification of perfection in the form of Galahad, a virgin wielding the power of God. Galahad's life, uniquely entirely without sin, makes him a model of a holy knight that cannot be emulated through secular chivalry.

Mordred and his half-brother Agravain succeed in revealing Guinevere's adultery and Arthur sentences her to burn. Lancelot's rescue party raids the execution, killing several loyal knights of the Round Table, including Gawain's brothers Gareth and Gaheris. Gawain, bent on revenge, prompts Arthur into a long and bitter war with Lancelot. After they leave to pursue Lancelot in France, where Gawain is mortally injured in a duel with Lancelot (and later finally reconciles with him on his death bed), Mordred seizes the throne and takes control of Arthur's kingdom. At Battle of Camlann, the bloody final battle between Mordred's followers and Arthur's remaining loyalists in England, Arthur kills Mordred but is himself gravely wounded. As Arthur is dying, the lone survivor Bedivere casts Excalibur away, and Morgan and Nimue come to take Arthur to Avalon. Following the passing of King Arthur, who is succeeded by Constantine, Malory provides a Dramatic structure#Catastrophe, denouement about the later deaths of Bedivere, Guinevere, and Lancelot and his kinsmen.

Writing the eponymous final book, Malory used the version of Arthur's death derived primarily from parts of the Lancelot-Grail, Vulgate ''Mort Artu'' and, as a secondary source, from the English Stanzaic ''Morte Arthur'' (or, in another possibility, a hypothetical now-lost French modification of the ''Mort Artu'' was a common source of both of these texts). In the words of George Brown (medievalist), George Brown, the book "celebrates the greatness of the Arthurian world on the eve of its ruin. As the magnificent fellowship turns violently upon itself, death and destruction also produce repentance, forgiveness, and salvation."

Mordred and his half-brother Agravain succeed in revealing Guinevere's adultery and Arthur sentences her to burn. Lancelot's rescue party raids the execution, killing several loyal knights of the Round Table, including Gawain's brothers Gareth and Gaheris. Gawain, bent on revenge, prompts Arthur into a long and bitter war with Lancelot. After they leave to pursue Lancelot in France, where Gawain is mortally injured in a duel with Lancelot (and later finally reconciles with him on his death bed), Mordred seizes the throne and takes control of Arthur's kingdom. At Battle of Camlann, the bloody final battle between Mordred's followers and Arthur's remaining loyalists in England, Arthur kills Mordred but is himself gravely wounded. As Arthur is dying, the lone survivor Bedivere casts Excalibur away, and Morgan and Nimue come to take Arthur to Avalon. Following the passing of King Arthur, who is succeeded by Constantine, Malory provides a Dramatic structure#Catastrophe, denouement about the later deaths of Bedivere, Guinevere, and Lancelot and his kinsmen.

Writing the eponymous final book, Malory used the version of Arthur's death derived primarily from parts of the Lancelot-Grail, Vulgate ''Mort Artu'' and, as a secondary source, from the English Stanzaic ''Morte Arthur'' (or, in another possibility, a hypothetical now-lost French modification of the ''Mort Artu'' was a common source of both of these texts). In the words of George Brown (medievalist), George Brown, the book "celebrates the greatness of the Arthurian world on the eve of its ruin. As the magnificent fellowship turns violently upon itself, death and destruction also produce repentance, forgiveness, and salvation."

Following the lapse of nearly two centuries since the last printing, the year 1816 saw a new edition by Alexander Chalmers, illustrated by Thomas Uwins (as ''The History of the Renowned Prince Arthur, King of Britain; with His Life and Death, and All His Glorious Battles. Likewise, the Noble Acts and Heroic Deeds of His Valiant Knights of the Round Table''), as well as another one by Joseph Haslewood (as ''La Mort D'Arthur: The Most Ancient and Famous History of the Renowned Prince Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table''), both based on the 1634 Stansby edition. Soon afterward, William Upcott's edition directly based on the rediscovered Morgan copy of the first print version was published in 1817 along with Robert Southey’s introduction and notes including summaries of the original French material from the Vulgate tradition. It then became the basis for subsequent editions until the 1934 discovery of the Winchester Manuscript.

Modernized editions update the late Middle English spelling, update some pronouns, and re-punctuate and re-paragraph the text. Others furthermore update the phrasing and vocabulary to contemporary Modern English. The following sentence (from Caxton's preface, addressed to the reader) is an example written in Middle English and then in Modern English:

:''Doo after the good and leve the evyl, and it shal brynge you to good fame and renomme.''Bryan (1994), p. xii. (Do after the good and leave the evil, and it shall bring you to good fame and renown.Bryan, ed. (1999), p. xviii.)

Following the lapse of nearly two centuries since the last printing, the year 1816 saw a new edition by Alexander Chalmers, illustrated by Thomas Uwins (as ''The History of the Renowned Prince Arthur, King of Britain; with His Life and Death, and All His Glorious Battles. Likewise, the Noble Acts and Heroic Deeds of His Valiant Knights of the Round Table''), as well as another one by Joseph Haslewood (as ''La Mort D'Arthur: The Most Ancient and Famous History of the Renowned Prince Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table''), both based on the 1634 Stansby edition. Soon afterward, William Upcott's edition directly based on the rediscovered Morgan copy of the first print version was published in 1817 along with Robert Southey’s introduction and notes including summaries of the original French material from the Vulgate tradition. It then became the basis for subsequent editions until the 1934 discovery of the Winchester Manuscript.

Modernized editions update the late Middle English spelling, update some pronouns, and re-punctuate and re-paragraph the text. Others furthermore update the phrasing and vocabulary to contemporary Modern English. The following sentence (from Caxton's preface, addressed to the reader) is an example written in Middle English and then in Modern English:

:''Doo after the good and leve the evyl, and it shal brynge you to good fame and renomme.''Bryan (1994), p. xii. (Do after the good and leave the evil, and it shall bring you to good fame and renown.Bryan, ed. (1999), p. xviii.)

Since the 19th-century Arthurian revival, there have been numerous modern republications, retellings and adaptations of ''Le Morte d'Arthur''. A few of them are listed below (see also the following #Bibliography, Bibliography section):

* Malory's book inspired Reginald Heber's unfinished poem ''Morte D'Arthur''. A fragment of it was published by Heber's widow in 1830.

* Victorian poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Alfred Tennyson retold the legends in the poetry volume ''Idylls of the King'' (1859 and 1885). His work focuses on ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' and the ''Mabinogion'', with many expansions, additions and several adaptations, such as the fate of Guinevere (in Malory, she is sentenced to be burnt at the stake but is rescued by Lancelot; in the ''Idylls'', Guinevere flees to a convent, is forgiven by Arthur, repents and serves in the convent until her death).

* James Thomas Knowles (1831–1908), James Thomas Knowles published ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' as ''The Legends of King Arthur and His Knights'' in 1860. Originally illustrated by George Housman Thomas, it has been subsequently illustrated by various other artists, including William Henry Margetson and Louis Rhead. The 1912 edition was illustrated by Lancelot Speed, who later also illustrated Rupert S. Holland's 1919 ''King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table'' that was based on Knowles with addition of some material from the 12th-century ''Perceval, the Story of the Grail''.

* In 1880, Sidney Lanier published a much expurgated rendition entitled ''The Boy's King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, Edited for Boys'', an enduringly popular children's adaptation, originally illustrated by Alfred Kappes. A new edition with illustrations by N. C. Wyeth was first published in 1917. This version was later incorporated into Grosset and Dunlap's series of books called the Illustrated Junior Library, and reprinted under the title ''King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table'' (1950).

* In 1892, London publisher J. M. Dent produced an illustrated edition of ''Le Morte Darthur'' in modern spelling, with illustrations by 20-year-old insurance office clerk and art student Aubrey Beardsley. It was issued in 12 parts between June 1893 and mid-1894, and met with only modest success, but was later described as Beardsley's first masterpiece, launching what has come to be known as the "Beardsley look".Dover Publications (1972). ''Beardsley's Illustrations for Le Morte Darthur'', Publisher's note & back cover. It was Beardsley's first major commission, and included nearly 585 chapter openings, borders, initials, ornaments and full- or double-page illustrations. The majority of the Dent edition illustrations were reprinted by Dover Publications in 1972 under the title ''Beardsley's Illustrations for Le Morte Darthur''. A facsimile of the Beardsley edition, complete with Malory's unabridged text, was published in the 1990s.

* Mary MacLeod's popular children's adaptation ''King Arthur and His Noble Knights: Stories From Sir Thomas Malory's Morte D'Arthur'' was first published with illustrations by Arthur George Walker in 1900 and subsequently reprinted in various editions and in extracts in children's magazines.

* Beatrice Clay wrote a retelling first included in her ''Stories from Le Morte Darthur and the Mabinogion'' (1901). A retitled version, ''Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table'' (1905), features illustrations by Dora Curtis.

* In 1902, Andrew Lang published ''The Book of Romance'', a retelling of Malory illustrated by Henry Justice Ford. It was retitled as ''Tales of King Arthur and the Round Table'' in the 1909 edition.

* Howard Pyle wrote and illustrated a series of four books: ''The Story of King Arthur and His Knights'' (1903), ''The Story of the Champions of the Round Table'' (1905), ''The Story of Sir Launcelot and His Companions'' (1907), and ''The Story of the Grail and the Passing of King Arthur'' (1910). Rather than retell the stories as written, Pyle presented his own versions of select episodes enhanced with other tales and his own imagination.

* Another children adaptation, Henry Gilbert (author), Henry Gilbert's ''King Arthur's Knights: The Tales Retold for Boys and Girls'', was first published in 1911, originally illustrated by Walter Crane. Highly popular, it was reprinted many times until 1940, featuring also illustrations from other artists such as Frances Brundage and Thomas Heath Robinson.

* Alfred W. Pollard published an abridged edition of Malory in 1917, illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Pollard later also published a complete version in four volumes during 1910-1911 and in two volumes in 1920, with illustrations by William Russell Flint.

* T. H. White's ''The Once and Future King'' (1938–1977) is a famous and influential retelling of Malory's work. White rewrote the story in his own fashion. His rendition contains intentional and obvious anachronisms and social-political commentary on contemporary matters. White made Malory himself a character and bestowed upon him the highest praise.

* Pollard's 1910-1911 abridged edition of Malory provided basis for John W. Donaldson's 1943 book ''Arthur Pendragon of Britain''. It was illustrated by N. C. Wyeth son, Andrew Wyeth.

* Roger Lancelyn Green and Richard Lancelyn Green published ''King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table'' in 1953.

* Alex Blum's comic book retelling ''Knights of the Round Table'' was published in the ''Classics Illustrated'' series in 1953.

*

Since the 19th-century Arthurian revival, there have been numerous modern republications, retellings and adaptations of ''Le Morte d'Arthur''. A few of them are listed below (see also the following #Bibliography, Bibliography section):

* Malory's book inspired Reginald Heber's unfinished poem ''Morte D'Arthur''. A fragment of it was published by Heber's widow in 1830.

* Victorian poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Alfred Tennyson retold the legends in the poetry volume ''Idylls of the King'' (1859 and 1885). His work focuses on ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' and the ''Mabinogion'', with many expansions, additions and several adaptations, such as the fate of Guinevere (in Malory, she is sentenced to be burnt at the stake but is rescued by Lancelot; in the ''Idylls'', Guinevere flees to a convent, is forgiven by Arthur, repents and serves in the convent until her death).

* James Thomas Knowles (1831–1908), James Thomas Knowles published ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' as ''The Legends of King Arthur and His Knights'' in 1860. Originally illustrated by George Housman Thomas, it has been subsequently illustrated by various other artists, including William Henry Margetson and Louis Rhead. The 1912 edition was illustrated by Lancelot Speed, who later also illustrated Rupert S. Holland's 1919 ''King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table'' that was based on Knowles with addition of some material from the 12th-century ''Perceval, the Story of the Grail''.

* In 1880, Sidney Lanier published a much expurgated rendition entitled ''The Boy's King Arthur: Sir Thomas Malory's History of King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table, Edited for Boys'', an enduringly popular children's adaptation, originally illustrated by Alfred Kappes. A new edition with illustrations by N. C. Wyeth was first published in 1917. This version was later incorporated into Grosset and Dunlap's series of books called the Illustrated Junior Library, and reprinted under the title ''King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table'' (1950).

* In 1892, London publisher J. M. Dent produced an illustrated edition of ''Le Morte Darthur'' in modern spelling, with illustrations by 20-year-old insurance office clerk and art student Aubrey Beardsley. It was issued in 12 parts between June 1893 and mid-1894, and met with only modest success, but was later described as Beardsley's first masterpiece, launching what has come to be known as the "Beardsley look".Dover Publications (1972). ''Beardsley's Illustrations for Le Morte Darthur'', Publisher's note & back cover. It was Beardsley's first major commission, and included nearly 585 chapter openings, borders, initials, ornaments and full- or double-page illustrations. The majority of the Dent edition illustrations were reprinted by Dover Publications in 1972 under the title ''Beardsley's Illustrations for Le Morte Darthur''. A facsimile of the Beardsley edition, complete with Malory's unabridged text, was published in the 1990s.

* Mary MacLeod's popular children's adaptation ''King Arthur and His Noble Knights: Stories From Sir Thomas Malory's Morte D'Arthur'' was first published with illustrations by Arthur George Walker in 1900 and subsequently reprinted in various editions and in extracts in children's magazines.

* Beatrice Clay wrote a retelling first included in her ''Stories from Le Morte Darthur and the Mabinogion'' (1901). A retitled version, ''Stories of King Arthur and the Round Table'' (1905), features illustrations by Dora Curtis.

* In 1902, Andrew Lang published ''The Book of Romance'', a retelling of Malory illustrated by Henry Justice Ford. It was retitled as ''Tales of King Arthur and the Round Table'' in the 1909 edition.

* Howard Pyle wrote and illustrated a series of four books: ''The Story of King Arthur and His Knights'' (1903), ''The Story of the Champions of the Round Table'' (1905), ''The Story of Sir Launcelot and His Companions'' (1907), and ''The Story of the Grail and the Passing of King Arthur'' (1910). Rather than retell the stories as written, Pyle presented his own versions of select episodes enhanced with other tales and his own imagination.

* Another children adaptation, Henry Gilbert (author), Henry Gilbert's ''King Arthur's Knights: The Tales Retold for Boys and Girls'', was first published in 1911, originally illustrated by Walter Crane. Highly popular, it was reprinted many times until 1940, featuring also illustrations from other artists such as Frances Brundage and Thomas Heath Robinson.

* Alfred W. Pollard published an abridged edition of Malory in 1917, illustrated by Arthur Rackham. Pollard later also published a complete version in four volumes during 1910-1911 and in two volumes in 1920, with illustrations by William Russell Flint.

* T. H. White's ''The Once and Future King'' (1938–1977) is a famous and influential retelling of Malory's work. White rewrote the story in his own fashion. His rendition contains intentional and obvious anachronisms and social-political commentary on contemporary matters. White made Malory himself a character and bestowed upon him the highest praise.

* Pollard's 1910-1911 abridged edition of Malory provided basis for John W. Donaldson's 1943 book ''Arthur Pendragon of Britain''. It was illustrated by N. C. Wyeth son, Andrew Wyeth.

* Roger Lancelyn Green and Richard Lancelyn Green published ''King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table'' in 1953.

* Alex Blum's comic book retelling ''Knights of the Round Table'' was published in the ''Classics Illustrated'' series in 1953.

*

Le Morte Darthur

Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse: University of Michigan. ** Modernised spelling: *** Malory, Sir Thomas. ''Le Morte d'Arthur''. Ed. Matthews, John (2000). Illustrated by Ferguson, Anna-Marie. London: Cassell. . (The introduction by John Matthews praises the Winchester text but then states this edition is based on the Pollard version of the Caxton text, with eight additions from the Winchester manuscript.) *** _________. ''Le Morte Darthur''. Introduction by Moore, Helen (1996). Herefordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd. . (Seemingly based on the Pollard text.) *** _________. ''Le morte d'Arthur''. Introduction by Bryan, Elizabeth J. (1994). New York: Modern Library. . (Pollard text.) *** _________. ''Le Morte d'Arthur''. Ed. Cowen, Janet (1970). Introduction by Lawlor, John. 2 vols. London: Penguin. . *** _________. ''Le Morte d'Arthur''. Ed. Rhys, John (1906). (Everyman's Library 45 & 46.) London: Dent; London: J. M. Dent; New York: E. P. Dutton. Released in paperback format in 1976: . (Text based on an earlier modernised Dent edition of 1897.) *** _________. ''Le Morte Darthur: Sir Thomas Malory's Book of King Arthur and of his Noble Knights of the Round Table,''. Ed. Pollard, A. W. (1903). 2 vol. New York: Macmillan. (Text corrected from the bowdlerised 1868 Macmillan edition edited by Sir Edward Strachey.) Available on the web at: *** _________. ''Le Morte Darthur.'' Ed. Simmon, F. J. (1893–94). Illustrated by Beardsley, Aubrey. 2 vol. London: Dent. *** Project Gutenberg

Le Morte Darthur: Volume 1 (books 1–9)

an

Le Morte Darthur: Volume 2 (books 10–21)

(Plain text.) *** Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library

an

(HTML.) **

(HTML with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley from the Dent edition of 1893–94.)

Glossary to Book 1

an

Glossary to Book 2

(PDF)

an

selections by Alice D. Greenwood with bibliography from the ''Cambridge History of English Literature''.

Arthur Dies at the End

by Jeff Wikstrom * About the Winchester manuscript: *

(Contains links to the first public announcements concerning the Winchester manuscript from ''The Daily Telegraph'', ''The Times'', and ''The Times Literary Supplement''.) *

(link offline on Oct. 25, 2011; according to message o

"September 2011: Most of the pages below are being renovated, so the links are (temporarily) inactive.") *

"Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte Darthur, 1947-1987: Author, Title, Text"

''Speculum'' Vol. 62, No. 4 (Oct., 1987), pp. 878–897. The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Medieval Academy of America * Gweneth Whitteridge, Whitteridge, Gweneth. "The Identity of Sir Thomas Malory, Knight-Prisoner." ''The Review of English Studies''; 24.95 (1973): 257–265. JSTOR. Web. 30 November 2009.

Full Text of Volume One

– at Project Gutenberg

Full Text of Volume Two

– at Project Gutenberg *

Different copies of ''La Mort d'Arthur''

at the Internet Archive {{DEFAULTSORT:Morte D'arthur, Le 1485 books Adaptations of works by Chrétien de Troyes Arthurian literature in Middle English Books published posthumously British books Medieval literature Prison writings Romance (genre) Works by Thomas Malory

Middle French

Middle French (french: moyen français) is a historical division of the French language that covers the period from the 14th to the 16th century. It is a period of transition during which:

* the French language became clearly distinguished from t ...

for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory

Sir Thomas Malory was an English writer, the author of '' Le Morte d'Arthur'', the classic English-language chronicle of the Arthurian legend, compiled and in most cases translated from French sources. The most popular version of '' Le Morte d' ...

of tales about the legendary King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

, Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; cy, Gwenhwyfar ; br, Gwenivar, kw, Gwynnever), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First ment ...

, Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), also written as Launcelot and other variants (such as early German ''Lanzelet'', early French ''Lanselos'', early Welsh ''Lanslod Lak'', Italian ''Lancillotto'', Spanish ''Lanzarote del Lago' ...

, Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

and the Knights of the Round Table

The Knights of the Round Table ( cy, Marchogion y Ford Gron, kw, Marghekyon an Moos Krenn, br, Marc'hegien an Daol Grenn) are the knights of the fellowship of King Arthur in the literary cycle of the Matter of Britain. First appearing in lit ...

, along with their respective folklore. In order to tell a "complete" story of Arthur from his conception to his death, Malory compiled, rearranged, interpreted and modified material from various French and English sources. Today, this is one of the best-known works of Arthurian literature

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

. Many authors since the 19th-century revival of the legend have used Malory as their principal source.

Apparently written in prison at the end of the medieval English era, ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' was completed by Malory around 1470 and was first published in a printed edition in 1485 by William Caxton

William Caxton ( – ) was an English merchant, diplomat and writer. He is thought to be the first person to introduce a printing press into England, in 1476, and as a printer (publisher), printer to be the first English retailer of printed boo ...

. Until the discovery of the Winchester Manuscript

' (originally written as '; inaccurate Middle French for "The Death of Arthur") is a 15th-century Middle English prose reworking by Sir Thomas Malory of tales about the legendary King Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin and the Knights of the R ...

in 1934, the 1485 edition was considered the earliest known text of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' and that closest to Malory's original version.Bryan, Elizabeth J. (1994/1999). "Sir Thomas Malory", ''Le Morte D'Arthur'', p. vii. Modern Library. New York. . Modern editions under myriad titles are inevitably variable, changing spelling, grammar and pronouns for the convenience of readers of modern English, as well as often abridging or revising the material.

History

Authorship

The exact identity of the author of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' has long been the subject of speculation, owing to the fact that at least six historical figures bore the name of "Sir Thomas Malory" (in various spellings) during the late 15th century. In the work, the author describes himself as "Knyght presoner Thomas Malleorre" ("Sir Thomas Maleore" according to the publisherWilliam Caxton

William Caxton ( – ) was an English merchant, diplomat and writer. He is thought to be the first person to introduce a printing press into England, in 1476, and as a printer (publisher), printer to be the first English retailer of printed boo ...

). This is taken as supporting evidence for the identification most widely accepted by scholars: that the author was the Thomas Malory born in the year 1416, to Sir John Malory of Newbold Revel

Newbold Revel is an 18th-century country house in the village of Stretton-under-Fosse, Warwickshire, England. It is now used by HM Prison Service as a training college and is a Grade II* listed building.

The house was built in 1716 for Sir Fulw ...

, Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

, England.

Sir Thomas inherited the family estate in 1434, but by 1450 he was fully engaged in a life of crime. As early as 1433, he had been accused of theft, but the more serious allegations against him included that of the attempted murder of Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham

Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 6th Earl of Stafford, 7th Baron Stafford, (December 1402 – 10 July 1460) of Stafford Castle in Staffordshire, was an English nobleman and a military commander in the Hundred Years' War and t ...

, an accusation of at least two rapes, and that he had attacked and robbed Coombe Abbey. Malory was first arrested and imprisoned in 1451 for the ambush of Buckingham, but was released early in 1452. By March, he was back in the Marshalsea

The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, just south of the River Thames. Although it housed a variety of prisoners, including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition, it became known, ...

prison and then in Colchester

Colchester ( ) is a city in Essex, in the East of England. It had a population of 122,000 in 2011. The demonym is Colcestrian.

Colchester occupies the site of Camulodunum, the first major city in Roman Britain and its first capital. Colches ...

, escaping on multiple occasions. In 1461, he was granted a pardon by King Henry VI, returning to live at his estate. Although originally allied to the House of York

The House of York was a cadet branch of the English royal House of Plantagenet. Three of its members became kings of England in the late 15th century. The House of York descended in the male line from Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York, ...

, after his release Malory changed his allegiance to the House of Lancaster

The House of Lancaster was a cadet branch of the royal House of Plantagenet. The first house was created when King Henry III of England created the Earldom of Lancasterfrom which the house was namedfor his second son Edmund Crouchback in 126 ...

. This led to him being imprisoned yet again in 1468, when he led an ill-fated plot to overthrow King Edward IV. It was during this final stint at Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

in London that he is believed to have written ''Le Morte d'Arthur''. Malory was released in October 1470, when Henry VI returned to the throne, but died only five months later.

The most likely other candidate who has received support as the possible author of ''Le Morte Darthur'' is Thomas Mallory of Papworth St Agnes in Huntingdonshire

Huntingdonshire (; abbreviated Hunts) is a non-metropolitan district of Cambridgeshire and a historic county of England. The district council is based in Huntingdon. Other towns include St Ives, Godmanchester, St Neots and Ramsey. The popul ...

, whose will, written in Latin and dated 16 September 1469, was described in an article by T. A. Martin in the ''Athenaeum

Athenaeum may refer to:

Books and periodicals

* ''Athenaeum'' (German magazine), a journal of German Romanticism, established 1798

* ''Athenaeum'' (British magazine), a weekly London literary magazine 1828–1921

* ''The Athenaeum'' (Acadia U ...

'' magazine in September 1897. This Mallory was born in Shropshire in 1425, the son of Sir William Mallory, although there is no indication in the will that he was himself a knight; he died within six weeks of the will being made. It has been suggested that the fact that he appears to have been brought up in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershire ...

may account for the traces of Lincolnshire dialect in ''Le Morte Darthur''.

Sources

As Elizabeth Bryan wrote of Malory's contribution to Arthurian legend in her introduction to a modern edition of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'', "Malory did not invent the stories in this collection; he translated and compiled them. Malory in fact translated Arthurian stories that already existed in 13th-century French prose (the so-calledOld French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intelligib ...

Vulgate romances) and compiled them together with Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

sources (the Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'' and the Stanzaic ''Morte Arthur'') to create this text."Bryan (1994), pp. viii–ix.

Within his narration, Malory refers to drawing it from a singular "Freynshe booke", in addition to also unspecified "other bookis". In addition to the vast Vulgate Cycle in its different variants, as well as the English poems ''Morte Arthur'' and ''Morte Arthure'', Malory's other original source texts were identified as several French standalone chivalric romance

As a literary genre, the chivalric romance is a type of prose and verse narrative that was popular in the noble courts of High Medieval and Early Modern Europe. They were fantastic stories about marvel-filled adventures, often of a chivalric k ...

s, including ''Erec et Enide

, original_title_lang = fro

, translator =

, written = c. 1170

, country =

, language = Old French

, subject = Arthurian legend

, genre = Chivalric romance

, form ...

'', ''L'âtre périlleux

''L'âtre périlleux'' (Old French ''L'atre perillous'',Ms. 2168 fr. of the BnFf. 1r at the top of the page. English The Perilous CemeteryN. Black, 1994.M.-L., Charue, 1998.) is an anonymous 13th century poem written in Old French in which Gawain i ...

'', ''Perlesvaus

''Perlesvaus'', also called ''Li Hauz Livres du Graal'' (''The High Book of the Grail''), is an Old French Arthurian romance dating to the first decade of the 13th century. It purports to be a continuation of Chrétien de Troyes' unfinished ''Perc ...

'', and '' Yvain ou le Chevalier au Lion'' (or its English version, ''Ywain and Gawain

''Ywain and Gawain'' is an early-14th century Middle English Arthurian verse romance based quite closely upon the late-12th-century Old French romance '' The Knight of the Lion'' by Chrétien de Troyes.

Plot

Ywain, one of King Arthur's Knights of ...

''), as well as John Hardyng

John Hardyng (or Harding; 1378–1465) was an English chronicler. He was born in Northern England.

Biography

As a boy Hardyng entered the service of Sir Henry Percy (Hotspur), with whom he was present at the Battle of Shrewsbury (1403). He the ...

's English ''Chronicle''. The English poem '' The Weddynge of Syr Gawen'' is uncertainly regarded as either just another of these or possibly actually Malory's own work. His assorted other sources might have included a 5th-century Roman military manual, '' De re militari''.

Publication and impact

''Le Morte d'Arthur'' was completed in 1469 or 1470 ("the ninth year of the reign of King Edward IV"), according to a note at the end of the book.Lumiansky (1987), p. 878. This note is available only in the Pierpont Morgan Library version of the book, since in the Winchester manuscript and the John Rylands Library copy the final pages are missing. It is believed that Malory's original title intended was to be ''The hoole booke of kyng Arthur & of his noble knyghtes of the rounde table'', and only its final section to be named ''Le Morte Darthur''. At the end of the work, Caxton added: "Thus endeth this noble & joyous book entytled le morte Darthur, Notwythstondyng it treateth of the byrth, lyf, and actes of the sayd kynge Arthur; of his noble knyghtes of the rounde table, theyr meruayllous enquestes and aduentures, thachyeuyng of the sangreal, & in thende the dolorous deth & departynge out of this worlde of them al." Caxton separated Malory's eight books into 21 books, subdivided the books into a total of 506 chapters, added a summary of each chapter, and added a colophon to the entire book.Bryan (2004), p. ix The first printing of Malory's work was made by Caxton in 1485. Only two copies of this original printing are known to exist, in the collections of theMorgan Library & Museum

The Morgan Library & Museum, formerly the Pierpont Morgan Library, is a museum and research library in the Murray Hill neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. It is situated at 225 Madison Avenue, between 36th Street to the south and 37th S ...

in New York and the John Rylands Library

The John Rylands Research Institute and Library is a late-Victorian neo-Gothic building on Deansgate in Manchester, England. It is part of the University of Manchester. The library, which opened to the public in 1900, was founded by Enriquet ...

in Manchester. It proved popular and was reprinted in an illustrated form with some additions and changes in 1498 and 1529 by Wynkyn de Worde

Wynkyn de Worde (died 1534) was a printer and publisher in London known for his work with William Caxton, and is recognised as the first to popularise the products of the printing press in England.

Name

Wynkyn de Worde was a German immigr ...

who succeeded to Caxton's press. Three more editions were published before the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

: William Copland's (1557), Thomas East

Thomas East, (also spelled Easte, Est, or Este) (''c.''1540 – January 1609), was an English printer who specialised in music. He has been described as a publisher, but that claim is debatable (the specialties of printer and bookseller/publish ...

's (1585), and William Stansby

William Stansby (1572–1638) was a London printer and publisher of the Jacobean and Caroline eras, working under his own name from 1610. One of the most prolific printers of his time, Stansby is best remembered for publishing the landmark first ...

's (1634), each of which contained additional changes and errors (Stansby's being notably poorly translated and highly censored). Thereafter, the book went out of fashion until the Romanticist

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

revival of interest in all things medieval.

The British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

summarizes the importance of Malory's work thus: "It was probably always a popular work: it was first printed by William Caxton (...) and has been read by generations of readers ever since. In a literary sense, Malory’s text is the most important of all the treatments of Arthurian legend in English language, influencing writers as diverse as Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; 1552/1553 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognized as one of the premier craftsmen of ...

, Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

, Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

and John Steinbeck

John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. (; February 27, 1902 – December 20, 1968) was an American writer and the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature winner "for his realistic and imaginative writings, combining as they do sympathetic humor and keen social ...

."

The Winchester Manuscript

An assistant master atWinchester College

Winchester College is a public school (fee-charging independent day and boarding school) in Winchester, Hampshire, England. It was founded by William of Wykeham in 1382 and has existed in its present location ever since. It is the oldest of the ...

, Walter Fraser Oakeshott

Sir Walter Fraser Oakeshott (11 November 1903 – 13 October 1987) was a schoolmaster and academic, who was Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford. He is best known for discovering the Winchester Manuscript of Sir Thomas Malory's ''Le Mort ...

discovered a previously unknown manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printing, printed or repr ...

copy of the work in June 1934, during the cataloguing of the college's library. Newspaper accounts announced that what Caxton had published in 1485 was not exactly what Malory had written. Oakeshott published "The Finding of the Manuscript" in 1963, chronicling the initial event and his realization that "this indeed was Malory," with "startling evidence of revision" in the Caxton edition.Walter F. Oakeshott, "The Finding of the Manuscript," ''Essays on Malory'', ed. J. A. W. Bennett (Oxford: Clarendon, 1963), 1–6. This manuscript is now in the British Library's collection.

Malory scholar Eugène Vinaver

Eugène Vinaver (russian: Евгений Максимович Винавер ''Yevgeniĭ Maksimovich Vinaver'', 18 June 1899 – 21 July 1979) was a Russian-born British literary scholar who is best known today for his edition of the works of Sir ...

examined the manuscript shortly after its discovery. Oakeshott was encouraged to produce an edition himself, but he ceded the project to Vinaver. Based on his initial study of the manuscript, Oakeshott concluded in 1935 that the copy from which Caxton printed his edition "was already subdivided into books and sections." Vinaver made an exhaustive comparison of the manuscript with Caxton's edition and reached similar conclusions. Microscopic examination revealed that ink smudges on the Winchester manuscript are offsets of newly printed pages set in Caxton's own font, which indicates that the Winchester Manuscript was in Caxton's print shop. The manuscript is believed to be closer on the whole to Malory's original and does not have the book and chapter divisions for which Caxton takes credit in his preface. The manuscript has been digitised by a Japanese team, who note that "the text is imperfect, as the manuscript lacks the first and last quires and few leaves. The most striking feature of the manuscript is the extensive use of red ink."

In his 1947 publication of ''The Works of Sir Thomas Malory'', Vinaver argued that Malory wrote not a single book, but rather a series of Arthurian tales, each of which is an internally consistent and independent work. However, William Matthews pointed out that Malory's later tales make frequent references to the earlier events, suggesting that he had wanted the tales to cohere better but had not sufficiently revised the whole text to achieve this. This was followed by much debate in the late 20th-century academia over which version is superior, Caxton's print or Malory's original vision.

Caxton's edition differs from the Winchester manuscript in many places. As well as numerous small differences on every page there is also a major difference both in style and content in Malory's Book II (Caxton's Book V), describing the war with the Emperor Lucius, where Caxton's version is much shorter. In addition, the Winchester manuscript has none of the customary marks indicating to the compositor where chapter headings and so on were to be added. It has therefore been argued that the Winchester manuscript was not the copy from which Caxton prepared his edition; rather it seems that Caxton either wrote out a different version himself for the use of his compositor, or used another version prepared by Malory.

The Winchester manuscript does not appear to have been copied out by Malory himself; rather, it seems to have been a presentation copy made by two scribes who, judging from certain dialect forms which they introduced into the text, appear to have come from West Northamptonshire

West Northamptonshire is a unitary authority area covering part of the ceremonial county of Northamptonshire, England, created in 2021. By far the largest settlement in West Northamptonshire is the county town of Northampton. Its other signif ...

. Apart from these forms, both the Winchester manuscript and the Caxton edition show some more northerly dialect forms which, in the judgement of the Middle English dialect expert Angus McIntosh are closest to the dialect of Lincolnshire. McIntosh argues, however, that this does not necessarily rule out the Warwickshire Malory as the possible author; he points out that it could be that the Warwickshire Malory consciously imitated the style and vocabulary of romance literature typical of the period.

Overview

Style

Like other English prose in the 15th century, ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' was highly influenced by French writings, but Malory blends these with other English verse and prose forms. The Middle English of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' is much closer toEarly Modern English

Early Modern English or Early New English (sometimes abbreviated EModE, EMnE, or ENE) is the stage of the English language from the beginning of the Tudor period to the English Interregnum and Restoration, or from the transition from Middle E ...

than the Middle English of Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

's ''Canterbury Tales

''The Canterbury Tales'' ( enm, Tales of Caunterbury) is a collection of twenty-four stories that runs to over 17,000 lines written in Middle English by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1387 and 1400. It is widely regarded as Chaucer's ''magnum opus' ...

'' (the publication of Chaucer's work by Caxton was a precursor to Caxton's publication of Malory); if the spelling is modernized, it reads almost like Elizabethan

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The symbol of Britannia (a female personifi ...

English. Where the ''Canterbury Tales'' are in Middle English, Malory extends "one hand to Chaucer, and one to Spenser," by constructing a manuscript which is hard to place in one category. Malory's writing can be divisive today: sometimes seen as simplistic from an artistic viewpoint, "rambling" and full of repetitions, yet there are also opposite opinions, such as of those regarding it a "supreme aesthetic accomplishment". Because there is so much lengthy ground to cover, Malory uses "so—and—then," often to transition his retelling of the stories that become episodes instead of instances that can stand on their own.

Setting and themes

Most of the events take place in a

Most of the events take place in a historical fantasy

Historical fantasy is a category of fantasy and genre of historical fiction that incorporates fantastic elements (such as magic) into a more "realistic" narrative. There is much crossover with other subgenres of fantasy; those classed as Arthu ...

version of Britain and France at an unspecified time (on occasion, the plot ventures farther afield, to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and Sarras

Sarras is a mystical island to which the Holy Grail is brought in the Arthurian legend. In the Lancelot-Grail Cycle, Joseph of Arimathea and his followers visit the island on their way to Britain; while there Joseph's son Josephus is invested as ...

, and recalls Biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

tales from the ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

). Arthurian myth is set during the 5th to 6th centuries, however Malory's telling contains many anachronisms and makes no effort at historical accuracy–even more so than his sources. Earlier romance authors have already depicted the " Dark Ages" times of Arthur as a familiar, High

High may refer to:

Science and technology

* Height

* High (atmospheric), a high-pressure area

* High (computability), a quality of a Turing degree, in computability theory

* High (tectonics), in geology an area where relative tectonic uplift ...

-to-Late Medieval

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

style world of armored knights and grand castles taking place of the Post-Roman warriors and forts. Malory further modernized the legend by conflating the Celtic Britain with his own contemporary Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England (, ) was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from 12 July 927, when it emerged from various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

On 1 ...

(for example explicitly identifying Logres

Logres (among various other forms and spellings) is King Arthur's realm in the Matter of Britain. It derives from the medieval Welsh word '' Lloegyr'', a name of uncertain origin referring to South and Eastern England (''Lloegr'' in modern Welsh ...

as England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the ...

as Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

, and Astolat

Astolat (; French: Escalot) is a legendary castle and town of Great Britain named in Arthurian legends. It is the home of Elaine, "the lily maid of Astolat", as well of her father Sir Bernard and her brothers Lavaine and Tirre. It is known as Sha ...

as Guildford

Guildford ()

is a town in west Surrey, around southwest of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The name "Guildf ...

) and, completely ahistorically, replacing the legend's Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

invaders with the Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

in the role of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

's foreign pagan enemies. Although Malory hearkens back to an age of idealized vision of knighthood, with chivalric

Chivalry, or the chivalric code, is an informal and varying code of conduct developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It was associated with the medieval Christian institution of knighthood; knights' and gentlemen's behaviours were governed b ...

codes of honor and jousting

Jousting is a martial game or hastilude between two horse riders wielding lances with blunted tips, often as part of a tournament (medieval), tournament. The primary aim was to replicate a clash of heavy cavalry, with each participant trying t ...

tournaments, his stories lack mentions of agricultural life or commerce. As noted by Ian Scott-Kilvert

Ian Stanley Scott-Kilvert OBE (26 May 1917 – 8 October 1989) was a British editor and translator. He worked for the British Council, editing a series of pamphlet essays on British writers, and was chairman of the Byron Society.'Deaths', ''T ...

, characters "consist almost entirely of fighting men, their wives or mistresses, with an occasional clerk or an enchanter, a fairy

A fairy (also fay, fae, fey, fair folk, or faerie) is a type of mythical being or legendary creature found in the folklore of multiple European cultures (including Celtic, Slavic, Germanic, English, and French folklore), a form of spirit, ...

or a fiend, a giant or a dwarf," and "time does not work on the heroes of Malory."

According to Charles W. Moorman III

Charles Wickliffe Moorman III, (May 24, 1925 – May 3, 1996) was an American writer, and professor at the University of Southern Mississippi from 1954 to 1990. He is notable for his writings on Middle English, medieval literature, the Arthuria ...

, Malory intended "to set down in English a unified Arthuriad which should have as its great theme the birth, the flowering, and the decline of an almost perfect earthy civilization." Moorman identified three main motifs going through the work: Sir Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), also written as Launcelot and other variants (such as early German ''Lanzelet'', early French ''Lanselos'', early Welsh ''Lanslod Lak'', Italian ''Lancillotto'', Spanish ''Lanzarote del Lago' ...

's and Queen Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; cy, Gwenhwyfar ; br, Gwenivar, kw, Gwynnever), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First ment ...

's affair; the long blood feud between the families of King Lot

King Lot , also spelled Loth or Lott (Lleu or Llew in Welsh), is a British monarch in Arthurian legend. He was introduced in Geoffrey of Monmouth's influential chronicle ''Historia Regum Britanniae'' that portrayed him as King Arthur's brother- ...

and King Pellinore

King Pellinore (alternatively ''Pellinor'', ''Pellynore'' and other variants) is the king of Listenoise (possibly the Lake District) or of "the Isles" (possibly Anglesey, or perhaps the medieval kingdom of the same name) in Arthurian legend. In ...

; and the mystical Grail Quest

The Holy Grail (french: Saint Graal, br, Graal Santel, cy, Greal Sanctaidd, kw, Gral) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miracul ...

. Each of these plots would define one of the causes of the downfall of Arthur's kingdom, namely "the failures in love, in loyalty, in religion."

Volumes and internal chronology

Prior to Caxton's reorganization, Malory's work originally consisted of eight books:

#The birth and rise of Arthur: "From the Marriage of King Uther unto King Arthur (that reigned after him and did many battles)" (''Fro the Maryage of Kynge Uther unto Kynge Arthure that regned aftir hym and ded many batayles'')

#Arthur's war against the resurgent Western Romans: "The Noble Tale Between King Arthur and Lucius the Emperor of Rome" (''The Noble Tale betwyxt Kynge Arthure and Lucius the Emperour of Rome'')

#The early adventures of Sir Lancelot: "The Noble Tale of Sir Launcelot of the Lake" (''The Noble Tale of Sir Launcelot du Lake'')

#The story of

Prior to Caxton's reorganization, Malory's work originally consisted of eight books:

#The birth and rise of Arthur: "From the Marriage of King Uther unto King Arthur (that reigned after him and did many battles)" (''Fro the Maryage of Kynge Uther unto Kynge Arthure that regned aftir hym and ded many batayles'')

#Arthur's war against the resurgent Western Romans: "The Noble Tale Between King Arthur and Lucius the Emperor of Rome" (''The Noble Tale betwyxt Kynge Arthure and Lucius the Emperour of Rome'')

#The early adventures of Sir Lancelot: "The Noble Tale of Sir Launcelot of the Lake" (''The Noble Tale of Sir Launcelot du Lake'')

#The story of Sir Gareth

Sir Gareth (; Old French: ''Guerehet'', ''Guerrehet'') is a Knight of the Round Table in Arthurian legend. He is the youngest son of King Lot and Queen Morgause, King Arthur's half-sister, thus making him Arthur's nephew, as well as brother ...

: "The Tale of Sir Gareth of Orkney" (''The Tale of Sir Gareth of Orkeney'')

#The legend of Tristan and Iseult

Tristan and Iseult, also known as Tristan and Isolde and other names, is a medieval chivalric romance told in numerous variations since the 12th century. Based on a Celtic legend and possibly other sources, the tale is a tragedy about the illic ...

: "The Book of Sir Tristram de Lyones" (originally split between ''The Fyrste Boke of Sir Trystrams de Lyones'' and ''The Secunde Boke of Sir Trystrams de Lyones'')

#The quest for the Grail

The Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) was an American lunar science mission in NASA's Discovery Program which used high-quality gravitational field mapping of the Moon to determine its interior structure. The two small spacecraf ...

: "The Noble Tale of the Sangreal" (''The Noble Tale of the Sankegreall'')

#The forbidden love between Lancelot and Guinevere: "Sir Launcelot and Queen Guenever" (''Sir Launcelot and Quene Gwenyvere'')

#The breakup of the Knights of the Round Table

The Knights of the Round Table ( cy, Marchogion y Ford Gron, kw, Marghekyon an Moos Krenn, br, Marc'hegien an Daol Grenn) are the knights of the fellowship of King Arthur in the literary cycle of the Matter of Britain. First appearing in lit ...

and the last battle

''The Last Battle'' is a high fantasy novel for children by C. S. Lewis, published by The Bodley Head in 1956. It was the seventh and final novel in ''The Chronicles of Narnia'' (1950–1956). Like the other novels in the series, it was illustr ...

of Arthur: "The Death of Arthur" (''The Deth of Arthur'')

Moorman attempted to put the books of the Winchester Manuscript in chronological order. In his analysis, Malory's intended chronology can be divided into three parts: Book I followed by a 20-year interval that includes some events of Book III and others; the 15-year-long period of Book V, also spanning Books IV, II and the later parts of III (in that order); and finally Books VI, VII and VIII in a straightforward sequence beginning with the closing part of Book V (the Joyous Gard

Joyous Gard (French ''Joyeuse Garde'' and other variants) is a castle featured in the Matter of Britain literature of the legend of King Arthur. It was introduced in the 13th-century French Prose ''Lancelot'' as the home and formidable fortress ...

section).

Synopsis

Book I (Caxton I–IV)

Arthur is born to the High King of Britain (Malory's "England")

Arthur is born to the High King of Britain (Malory's "England") Uther Pendragon

Uther Pendragon (Brittonic) (; cy, Ythyr Ben Dragwn, Uthyr Pendragon, Uthyr Bendragon), also known as King Uther, was a legendary King of the Britons in sub-Roman Britain (c. 6th century). Uther was also the father of King Arthur.

A few m ...

and his new wife Igraine, and then taken by the wizard Merlin

Merlin ( cy, Myrddin, kw, Marzhin, br, Merzhin) is a mythical figure prominently featured in the legend of King Arthur and best known as a mage, with several other main roles. His usual depiction, based on an amalgamation of historic and le ...

to be secretly fostered by Sir Ector

Sir Ector , sometimes Hector, Antor, or Ectorius, is the father of Sir Kay and the adoptive father of King Arthur in the Matter of Britain. Sometimes portrayed as a king instead of merely a lord, he has an estate in the country as well as pro ...

in the country in turmoil after the death of Uther. Years later, the now teenage Arthur suddenly becomes the ruler of the leaderless Britain when he removes the fated sword from the stone in the contest set up by Merlin, which proves his birthright that he himself had not been aware of. The newly crowned King Arthur and his followers including King Ban Ban is the King of Benwick or Benoic in Arthurian legend. First appearing by this name in the ''Lancelot propre'' part of the Vulgate Cycle, he is the father of Sir Lancelot and Sir Hector de Maris, and is the brother of King Bors. Ban largely cor ...

and King Bors

Bors (; french: link=no, Bohort) is the name of two knights in Arthurian legend, an elder and a younger. The two first appear in the 13th-century Lancelot-Grail romance prose cycle. Bors the Elder is the King of Gaunnes (Gannes/Gaunes/Ganis) du ...

go on to fight against rivals and rebels, ultimately winning the war in the great Battle of Bedegraine. Arthur prevails due to his military prowess and the prophetic and magical counsel of Merlin (later replaced by the sorceress Nimue

The Lady of the Lake (french: Dame du Lac, Demoiselle du Lac, cy, Arglwyddes y Llyn, kw, Arloedhes an Lynn, br, Itron al Lenn, it, Dama del Lago) is a name or a title used by several either fairy or fairy-like but human enchantresses in the ...

), further helped by the sword Excalibur

Excalibur () is the legendary sword of King Arthur, sometimes also attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. It was associated with the Arthurian legend very early on. Excalibur and the Sword in th ...

that Arthur received from a Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake (french: Dame du Lac, Demoiselle du Lac, cy, Arglwyddes y Llyn, kw, Arloedhes an Lynn, br, Itron al Lenn, it, Dama del Lago) is a name or a title used by several either fairy or fairy-like but human enchantresses in the ...

. With the help of reconciled rebels, Arthur also crushes a foreign invasion in the Battle of Clarence. With his throne secure, Arthur marries the also young Princess Guinevere

Guinevere ( ; cy, Gwenhwyfar ; br, Gwenivar, kw, Gwynnever), also often written in Modern English as Guenevere or Guenever, was, according to Arthurian legend, an early-medieval queen of Great Britain and the wife of King Arthur. First ment ...

and inherits the Round Table

The Round Table ( cy, y Ford Gron; kw, an Moos Krenn; br, an Daol Grenn; la, Mensa Rotunda) is King Arthur's famed table in the Arthurian legend, around which he and his knights congregate. As its name suggests, it has no head, implying that e ...

from her father, King Leodegrance. He then gathers his chief knights, including some of his former enemies who now joined him, at his capital Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the ...

and establishes the Round Table fellowship as all swear to the Pentecostal Oath as a guide for knightly conduct.

The narrative of Malory's first book is mainly based on the Merlin (poem), Prose ''Merlin'' in the version from the Post-Vulgate Cycle, Post-Vulgate ''Suite du Merlin'' (possibly on the manuscript Cambridge University Library, Additional 7071). It also includes the tale of Sir Balin, Balyn and Balan (a lengthy section which Malory called a "booke" in itself), as well as other episodes such as the hunt for the Questing Beast and the treason of Arthur's sorceress half-sister Queen Morgan le Fay in the plot involving her lover Accolon. Furthermore, it tells of begetting of Arthur's incestuous son Mordred by one of his other royal half-sisters, Morgause (though Arthur did not know her as his sister); on Merlin's advice, Arthur then takes every newborn boy in his kingdom and all but Mordred, who miraculously survives and eventually indeed kills his father in the end, perish at sea (this is mentioned matter-of-fact, with no apparent moral overtone).

Malory addresses his contemporary preoccupations with Legitimacy (political), legitimacy and societal unrest, which will appear throughout the rest of ''Le Morte d'Arthur''. According to Helen Cooper (professor), Helen Cooper in ''Sir Thomas Malory: Le Morte D'arthur – The Winchester Manuscript'', the prose style, which mimics historical documents of the time, lends an air of authority to the whole work. This allowed contemporaries to read the book as a history rather than as a work of fiction, therefore making it a model of order for Malory's violent and chaotic times during the Wars of the Roses. Malory's concern with legitimacy reflects Tudor period, 15th-century England, where many were claiming their rights to power through violence and bloodshed.

Book II (Caxton V)

The opening of the second volume finds Arthur and his kingdom without an enemy. His throne is secure, and his knights including Griflet and Sir Tor, Tor as well as Arthur's own nephews Gawain and Ywain (sons of Morgause and Morgan, respectively) have proven themselves in various battles and fantastic quests as told in the first volume. Seeking more glory, Arthur and his knights then go to the war against (fictitious) Lucius Tiberius, Emperor Lucius who has just demanded Britain to resume paying tribute. Departing from Geoffrey of Monmouth's literary tradition in which Mordred is left in charge (as this happens there near the end of the story), Malory's Arthur leaves his court in the hands of Constantine III of Britain, Constantine of Cornwall and sails to Normandy to meet his cousin Hoel. After that, the story details Arthur's march on Rome through Almaine (Germany) and Italy. Following a series of battles resulting in the great victory over Lucius and his allies, and the Roman Senate's surrender, Arthur is crowned a Western Emperor but instead arranges a proxy government and returns to Britain. This book is based mostly on the first half of the Middle English heroic poem Alliterative ''Morte Arthure'' (itself heavily based on Geoffrey's pseudo-chronicle ''Historia Regum Britanniae''). Caxton's print version is abridged by more than half compared to Malory's manuscript. Vinaver theorized that Malory originally wrote this part first as a standalone work, while without knowledge of French romances. In effect, there is a time lapse that includes Arthur's war with King Claudas in France.Book III (Caxton VI)

Going back to a time before Book II, Malory establishes Sir

Going back to a time before Book II, Malory establishes Sir Lancelot

Lancelot du Lac (French for Lancelot of the Lake), also written as Launcelot and other variants (such as early German ''Lanzelet'', early French ''Lanselos'', early Welsh ''Lanslod Lak'', Italian ''Lancillotto'', Spanish ''Lanzarote del Lago' ...

, a young French orphan prince, as King Arthur's most revered knight through numerous episodic adventures, some of which he presented in comedic manner. Lancelot always adheres to the Pentecostal Oath, assisting ladies in distress and giving mercy for honorable enemies he has defeated in combat. However, the world Lancelot lives in is too complicated for simple mandates and, although Lancelot aspires to live by an ethical code, the actions of others make it difficult. Other issues are demonstrated when Morgan le Fay enchants Lancelot, which reflects a feminization of magic, and in how the prominence of jousting tournament fighting in this tale indicates a shift away from battlefield warfare towards a more mediated and virtuous form of violence.

Lancelot's character had previously appeared in the chronologically later Book II, fighting for Arthur against the Romans. In Book III, based on parts of the French Lancelot-Grail, Prose ''Lancelot'' (mostly its 'Agravain' section, along with the chapel perilous episode taken from ''Perlesvaus

''Perlesvaus'', also called ''Li Hauz Livres du Graal'' (''The High Book of the Grail''), is an Old French Arthurian romance dating to the first decade of the 13th century. It purports to be a continuation of Chrétien de Troyes' unfinished ''Perc ...

''), Malory attempts to turn the focus of courtly love from adultery to service by having Lancelot dedicate doing everything he does for Queen Guinevere, the wife of his lord and friend Arthur, but avoid (for a time being) to committing to an adulterous relationship with her. Nevertheless, it is still her love that is the ultimate source of Lancelot's supreme knightly qualities, something that Malory himself did not appear to be fully comfortable with as it seems to have clashed with his personal ideal of knighthood. Although a catalyst of the fall of Camelot, as it was in the French romantic prose cycle tradition, the moral handling of the adultery between Lancelot and Guinevere in ''Le Morte'' implies their relationship is true and pure, as Malory focused on the ennobling aspects of courtly love.

Book IV (Caxton VII)

The fourth volume primarily deals with the adventures of the young Gareth ("Beaumains") in his long quest for the sibling ladies Lynette and Lyonesse, Lynette and Lioness. The youngest of Arthur's nephews by Morgause and Lot, Gareth hides his identity as a nameless squire at Camelot as to achieve his knighthood in the most honest and honorable way. While this particular story is not directly based on any existing text unlike most of the content of previous volumes, it resembles various Arthurian romances of the Fair Unknown type.

The fourth volume primarily deals with the adventures of the young Gareth ("Beaumains") in his long quest for the sibling ladies Lynette and Lyonesse, Lynette and Lioness. The youngest of Arthur's nephews by Morgause and Lot, Gareth hides his identity as a nameless squire at Camelot as to achieve his knighthood in the most honest and honorable way. While this particular story is not directly based on any existing text unlike most of the content of previous volumes, it resembles various Arthurian romances of the Fair Unknown type.

Book V (Caxton VIII–XII)

A collection of the tales about Sir Tristan of Lyonesse as well as a variety of other knights such as Sir Dinadan, Sir Lamorak, Sir Palamedes (Arthurian legend), Palamedes, Sir Alexander the Orphan (Tristan's young relative abducted by Morgan) and "La Cote Male Taile, La Cote de Male Tayle". After telling of Tristan's birth and childhood, its primary focus is on the doomed adulterous relationship between Tristan and the Iseult, Belle Isolde, wife of his villainous uncle Mark of Cornwall, King Mark. It also includes the retrospective story of how Sir Galahad was born to Sir Lancelot and Princess Elaine of Corbenic, followed by Lancelot's years of madness. Based mainly on the French vast Prose Tristan, Prose ''Tristan'', or its lost English adaptation (and possibly also the Middle English verse romance ''Sir Tristrem''), Malory's treatment of the legend of the young Cornish prince Tristan is the centerpiece of ''Le Morte d'Arthur'' as well as the longest of his eight books. The variety of episodes and the alleged lack of coherence in the Tristan narrative raise questions about its role in Malory's text. However, the book foreshadows the rest of the text as well as including and interacting with characters and tales discussed in other parts of the work. It can be seen as an exploration of secular chivalry and a discussion of honor or "worship" when it is founded in a sense of shame and pride. If ''Le Morte'' is viewed as a text in which Malory is attempting to define the concept of knighthood, then the tale of Tristan becomes its critique, rather than Malory attempting to create an ideal knight as he does in some of the other books.Book VI (Caxton XIII–XVII)

Malory's primary source for this long part was the Lancelot-Grail, Vulgate ''Queste del Saint Graal'', chronicling the adventures of many knights in their spiritual quest to achieve the Holy Grail. Gawain is the first to embark on the quest for the Grail. Other knights like Lancelot, Percival, and Bors the Younger, likewise undergo the quest, eventually achieved by Galahad. Their exploits are intermingled with encounters with maidens and hermits who offer advice and interpret dreams along the way.