Lang Hancock on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Langley Frederick George "Lang" Hancock (10 June 1909 27 March 1992) was an Australian

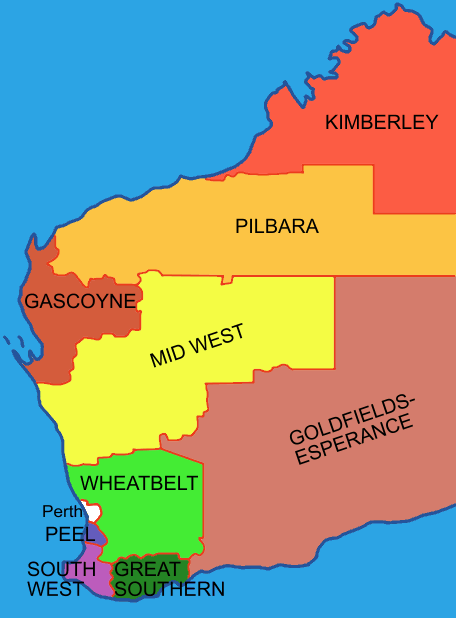

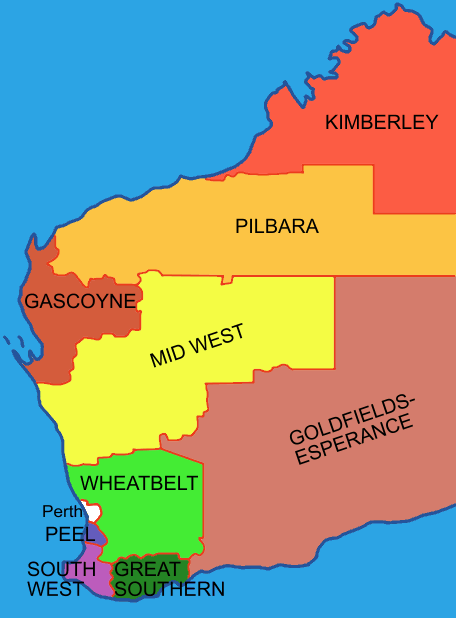

On 16 November 1952, Hancock claimed he discovered the world's largest deposit of iron ore in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Hancock said he was flying from Nunyerry to Perth with his wife, Hope, when they were forced by bad weather to fly low, through the gorges of the

On 16 November 1952, Hancock claimed he discovered the world's largest deposit of iron ore in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Hancock said he was flying from Nunyerry to Perth with his wife, Hope, when they were forced by bad weather to fly low, through the gorges of the

Although the marriage would later prove tumultuous, early on Hancock was clearly infatuated with his young wife. He gave her money and investments in

Although the marriage would later prove tumultuous, early on Hancock was clearly infatuated with his young wife. He gave her money and investments in

Hancock Prospecting website

ABC North-West WA, 8 July 2005.

Book review of Robert Wainwright's ''Rose''

from aussiereviews.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Hancock, Lang 1909 births 1992 deaths Volunteer Defence Corps soldiers People educated at Hale School People from Perth, Western Australia Pilbara Australian prospectors Lang Australian company founders Australian billionaires

iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the ...

magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

from Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to t ...

who maintained a high profile in the spheres of business and politics. Famous initially for discovering the world's largest iron ore deposit in 1952 and becoming one of the richest men in Australia, he is now perhaps best remembered for his marriage to the much-younger Rose Porteous, a Filipino woman and his former maid. Hancock's daughter, Gina Rinehart, was bitterly opposed to Hancock's relationship with Porteous. The conflicts between Rinehart and Porteous overshadowed his final years and continued until more than a decade after his death.

Aside from his extensively publicised personal life, Hancock's extreme right-wing views on the government of Australia

The Australian Government, also known as the Commonwealth Government, is the national government of Australia, a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy. Like other Westminster-style systems of government, the Australian Governmen ...

, Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

, and sociopolitical topics caused widespread controversy during his life.

Early life

Hancock was born on 10 June 1909 in Leederville, Perth, Western Australia. He was the oldest of four children born to Lilian () and George Hancock; his mother was born inSouth Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest o ...

and his father in Western Australia. His father's great-aunt was Emma Withnell, while a cousin was Sir Valston Hancock.Melville J. Davies, 'Hancock, Langley Frederick (Lang) (1909–1992)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hancock-langley-frederick-lang-17492/text29181, published online 2016, accessed online 15 August 2018. Hancock spent his early childhood on his family's station at Ashburton Downs, later moving to Mulga Downs Station in the north-west after his father, George Hancock, bought a farming estate there. After initially being educated at home, at the age of eight he began boarding at the St Aloysius Convent of Mercy

St Aloysius Convent of Mercy is a former Catholic convent located on Stirling Terrace in Toodyay, Western Australia, part of a larger site owned by the Church. This building is a part of the complex built by the Sisters of Mercy to provide a ...

in Toodyay. He later attended Hale School in Perth from 1924 to 1927, where he played for the school cricket and football teams. Upon completing his secondary education, he returned to Mulga Downs Station to help his father manage the property.

As a young man, Hancock was widely considered charming and charismatic. In 1935 he married 21-year-old Susette Maley, described by his biographer Debi Marshall as "an attractive blonde with laughing eyes". The couple lived at Mulga Downs for many years, but Maley pined for city life and eventually left Hancock to return to Perth. Their separation – formalised in 1944 – was amicable. Also in 1935, Hancock took over the management of Mulga Downs station from his father. He partnered with his old schoolmate E. A. "Peter" Wright in running the property, later boasting that no deals between the two men were ever sealed with anything stronger than a handshake

A handshake is a globally widespread, brief greeting or parting tradition in which two people grasp one of each other's like hands, in most cases accompanied by a brief up-and-down movement of the grasped hands. Customs surrounding handshakes a ...

.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, Hancock served in a militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

unit, the 11th (North-West) Battalion, Volunteer Defence Corps, and attained the rank of sergeant

Sergeant ( abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other ...

. On 4 August 1947, he married his second wife, Hope Margaret Nicholas, the mother of his only acknowledged child, Gina Rinehart. Lang and Hope remained married for 35 years, until her death in 1983 at the age of 66. In 2012, Hilda Kickett, who had long claimed to be Lang Hancock's illegitimate daughter, claimed that the late mining magnate had had an illicit affair with an Aboriginal cook on his property at Mulga Downs resulting in her conception. These claims have not been corroborated.

Wittenoom Gorge

As a child, Hancock showed a keen interest in mining and prospecting and discovered asbestos at Wittenoom Gorge at the age of ten. He staked a claim at Wittenoom in 1934 and began miningblue asbestos

Riebeckite is a sodium-rich member of the amphibole group of silicate minerals, chemical formula Na2(Fe2+3Fe3+2)Si8O22(OH)2. It forms a solid solution series with magnesioriebeckite. It crystallizes in the monoclinic system, usually as long prism ...

there in 1938 with the company Australian Blue Asbestos Australian Blue Asbestos Pty. Ltd. (ABA) was a company founded by Lang Hancock, operated between the years (1938–1966) responsible for the mining, bagging and distribution of blue asbestos or crocidolite, in Wittenoom, in northern Western Austra ...

.

The mine attracted the attention of national behemoths CSR Limited

CSR may refer to:

Biology

* Central serous retinopathy, a visual impairment

* Cheyne–Stokes respiration, an abnormal respiration pattern

* Child sex ratio, ratio between female and male births

* Class switch recombination, a process that cha ...

, who purchased the claim in 1943. Hancock retained a 49% share after the sale, but appears to have become quickly disillusioned about this arrangement, complaining that CSR viewed their 51% share as a licence to ignore his views. He sold the remainder of his claim in 1948. The mine would later become the source of much controversy, when hundreds of cases of asbestos-related diseases

Asbestos-related diseases are disorders of the lung and pleura caused by the inhalation of asbestos fibres. Asbestos-related diseases include non-malignant disorders such as asbestosis (pulmonary fibrosis due to asbestos), diffuse pleural thicken ...

came to light. He was aware of the dangers of asbestos prior to selling his stake in Australian Blue Asbestos (as recently discovered papers have shown) but never accepted any liability, nor have his companies since his death. Neither the Australian federal government nor the Western Australian state government have pursued his companies for damages as of 2017.

The Pilbara discovery

On 16 November 1952, Hancock claimed he discovered the world's largest deposit of iron ore in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Hancock said he was flying from Nunyerry to Perth with his wife, Hope, when they were forced by bad weather to fly low, through the gorges of the

On 16 November 1952, Hancock claimed he discovered the world's largest deposit of iron ore in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. Hancock said he was flying from Nunyerry to Perth with his wife, Hope, when they were forced by bad weather to fly low, through the gorges of the Turner River

The Turner River is a river in the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

Overview

The headwaters of the river rise below Pullcunah Hill and flows in a northerly direction and crosses the North West Coastal Highway approximately south of ...

. In Hancock's own words,

The story is widely accepted in modern descriptions of the discovery, but one biographer, Neill Phillipson, disputes Hancock's account. In ''Man of Iron'' he argues that there was no rain in the area of the Turner River on 16 November 1952 or indeed on ''any'' day in November 1952, a fact the Australian Bureau of Metrology confirms. Hancock returned to the area many times and, accompanied by prospector Ken McCamey, followed the iron ore over a distance of 112 km. He soon came to realise that he had stumbled across reserves of iron ore so vast that they could supply the entire world, thus confirming the discovery of the geologist Harry Page Woodward, who after his survey asserted:

After 1920 development of the Yampi Sound deposits started but exports to Japan were curtailed by the Commonwealth Government

The Australian Government, also known as the Commonwealth Government, is the national government of Australia, a federal parliamentary constitutional monarchy. Like other Westminster-style systems of government, the Australian Government ...

in 1938. Prospecting and exploration of other ore deposits continued until 1952 where an agreement between the Government of Western Australia

The Government of Western Australia, formally referred to as His Majesty's Government of Western Australia, is the Australian state democratic administrative authority of Western Australia. It is also commonly referred to as the WA Government o ...

and BHP to build a steel mill and smelter in Kwinana was established. All other iron ore, known or unknown, was reserved to the Crown for 9 years. Representations were made to the Commonwealth Government to have the embargo lifted and in 1960 Limited approval was granted for the export of iron ore from non-BHP deposits. This sparked a wave of intensive prospecting and exploration concentrated in the North West, the Hamersley Ranges in particular, where formation had been known but ore bodies not yet delineated. At this time Hancock revealed his discovery. Hancock had lobbied furiously for a decade to get the ban lifted and in 1961 was finally able to reveal his discovery and stake his claim.

In the mid sixties Hancock turned once more to Peter Wright and the pair entered into a deal with mining giant Rio Tinto Group

Rio Tinto Group is an Anglo-Australian multinational company that is the world's second-largest metals and mining corporation (behind BHP). The company was founded in 1873 when of a group of investors purchased a mine complex on the Rio Tint ...

to develop the iron ore find. Hancock named it "Hope Downs" after his wife. Under the terms of the deal Rio Tinto set up and still administer a mine in the area. Wright and Hancock walked away with annual royalties of A$25 million, split evenly between the two men. In 1990, Hancock was estimated

Estimation (or estimating) is the process of finding an estimate or approximation, which is a value that is usable for some purpose even if input data may be incomplete, uncertain, or unstable. The value is nonetheless usable because it is der ...

by ''Business Review Weekly

''BRW'' (formerly ''Business Review Weekly'') was an Australian business magazine published by the Fairfax Media group. The magazine was headquartered in Melbourne. It regularly compiled lists which rank corporations and individuals according to ...

'' to be worth a minimum of A$125 million.

Political activity

Although Lang Hancock never aspired to political office, he held strongconservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

political views and often entered the political arena. In addition to his activities in the 1950s, lobbying against government restrictions on the mining of iron ore, Hancock donated considerable sums of money to politicians of many political stripes. His political views aligned most closely with the Liberal and National Parties of Australia. He was a good friend and strong supporter of Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, establishe ...

Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of governm ...

Joh Bjelke-Petersen and donated A$632,000 to the Queensland National Party while Sir Joh was in charge. He gave A$314,000 to their counterparts in Western Australia, but also gave the Western Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also simply known as Labor, is the major centre-left political party in Australia, one of two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-right Liberal Party of Australia. The party forms t ...

A$985,000; because "at least they can't do any harm". Hancock had had a falling-out with Sir Charles Court and the Western Australian Liberals and was adamant that the Liberals should be kept out of power as long as possible.

Hancock also offered strong advice to the politicians he favoured. In 1977 he sent a Telex

The telex network is a station-to-station switched network of teleprinters similar to a telephone network, using telegraph-grade connecting circuits for two-way text-based messages. Telex was a major method of sending written messages electroni ...

to the then-Treasurer of Australia

The Treasurer of Australia (or Federal Treasurer) is a high ranking official and senior minister of the Crown in the Government of Australia who is the head of the Ministry of the Treasury which is responsible for government expenditure and ...

Sir Phillip Lynch

Sir Phillip Reginald Lynch KCMG (27 July 1933 – 19 June 1984) was an Australian politician who served in the House of Representatives from 1966 to 1982. He was deputy leader of the Liberal Party from 1972 to 1982, and served as a governmen ...

, telling him he needed to "stop money coming in to finance subversive activities, such as Friends of the Earth

Friends of the Earth International (FoEI) is an international network of environmental organizations in 73 countries. The organization was founded in 1969 in San Francisco by David Brower, Donald Aitken and Gary Soucie after Brower's split wi ...

, which is a well-heeled foreign operation." He also suggested to Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen that the Federal Government should attempt to censor the works of Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader (; born February 27, 1934) is an American political activist, author, lecturer, and attorney noted for his involvement in consumer protection, environmentalism, and government reform causes.

The son of Lebanese immigrants to the Un ...

and John Kenneth Galbraith

John Kenneth Galbraith (October 15, 1908 – April 29, 2006), also known as Ken Galbraith, was a Canadian-American economist, diplomat, public official, and intellectual. His books on economic topics were bestsellers from the 1950s through t ...

, lest they "wreck Fraser Fraser may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Fraser Point, South Orkney Islands

Australia

* Fraser, Australian Capital Territory, a suburb in the Canberra district of Belconnen

* Division of Fraser (Australian Capital Territory), a former federal e ...

's government".

In 1969 Hancock and his partner Peter Wright commenced publication in Perth of a weekly newspaper, ''The Sunday Independent'', principally to help further their mining interests. Faced with strong competition, the newspaper is thought never to have turned a profit, Hancock largely relinquishing his interest in it in the early 70s and Wright selling it to ''The Truth'' in 1984.

Hancock was a staunch proponent of small government and resented what he considered to be interference by the Commonwealth Government in Western Australian affairs. He declared before a state Royal Commission in 1991 that "I have always believed that the best government is the least government", and that "Although governments do not and cannot positively help business, they can be disruptive and destructive."

Hancock bankrolled an unsuccessful secessionist party in the 1970s, and in 1979 published a book, ''Wake Up Australia'', outlining what he saw as the case for Western Australian secession. The book was launched by Gina Rinehart and Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

Attitudes towards Aboriginal people

Hancock is quoted as saying, :"Mining in Australia occupies less than one-fifth of one percent of the total surface of our continent and yet it supports 14 million people. Nothing should be sacred from mining whether it's your ground, my ground, the blackfellow's ground or anybody else's. So the question ofAboriginal land rights

Indigenous land rights are the rights of Indigenous peoples to land and natural resources therein, either individually or collectively, mostly in colonised countries. Land and resource-related rights are of fundamental importance to Indigenou ...

and things of this nature shouldn’t exist."

In a 1984 television interview, Hancock suggested forcing unemployed indigenous Australians − specifically "the ones that are no good to themselves and who can't accept things, the half-castes" − to collect their welfare cheques from a central location. "And when they had gravitated there, I would dope the water up so that they were sterile and would breed themselves out in the future, and that would solve the problem."

Rose Porteous

In 1983, the same year as Hope Hancock's death, Rose Lacson (now Porteous) arrived in Australia from thePhilippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

on a three-month working visa. By the arrangement of Hancock's daughter, Gina Rinehart, Porteous began working as a maid

A maid, or housemaid or maidservant, is a female domestic worker. In the Victorian era domestic service was the second largest category of employment in England and Wales, after agricultural work. In developed Western nations, full-time maids ...

for the newly widowed Lang Hancock.

Hancock and Porteous became romantically involved over the course of Porteous' employment and they were wed on 6 July 1985 in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mounta ...

. It was a third marriage for each of them. Porteous, who was thirty-nine years younger than her husband, was often accused of gold digging because of their age disparity

Concepts of age disparity in sexual relationships, including what defines an age disparity, have developed over time and vary among societies. Differences in age preferences for mates can stem from partner availability, gender roles, and evoluti ...

, as well as being unfaithful and promiscuous. As Porteous later stated: "I have been accused of sleeping with every man in Australia ... I would have been a very busy woman." Hancock's daughter, Gina Rinehart, who stood to inherit his entire estate, did not attend the wedding.

Although the marriage would later prove tumultuous, early on Hancock was clearly infatuated with his young wife. He gave her money and investments in

Although the marriage would later prove tumultuous, early on Hancock was clearly infatuated with his young wife. He gave her money and investments in real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more genera ...

in the Sydney area. Porteous, in turn, helped Hancock to look and act like a much younger man, belying his eight decades. As ''The Age

''The Age'' is a daily newspaper in Melbourne, Australia, that has been published since 1854. Owned and published by Nine Entertainment, ''The Age'' primarily serves Victoria (Australia), Victoria, but copies also sell in Tasmania, the Austral ...

'' put it, "Rose made Lang feel younger, sprucing up his wardrobe, dying his hair and getting rid of his cane." Together they built the "Prix d'Amour", a lavish 16-block mansion overlooking the Swan River. The mansion, which was modelled after Tara, the plantation mansion from the movie '' Gone with the Wind'', was the setting for many large parties at which Hancock and Porteous would "dance into the night".

As the marriage wore on, however, the relationship between Lang and Rose began to break down. Rinehart would later claim that Hancock's bride had paid little attention to his worsening health, but had instead "screeched at him for money". Although there were many quarrels, the Hancocks remained married until Lang's death in 1992.

On 25 June 1992, less than three months after Hancock's death, Porteous married for the fourth time, to Hancock's long-time friend William Porteous. Rinehart was indignant at the haste with which her stepmother had remarried.

The Prix d'Amour, built in 1990, was bulldozed in March 2006. West Australian finance minister Max Evans mourned the loss of the home as the excavators moved in and recalled Hancock had been bemused by his wife's desire for the sprawling mansion:

"He'd say, 'Mr Evans, I don't know why Rose wants this house, I'd be happy sleeping in a transportable.' "

Mrs Porteous told him she'd always wanted to live in Prix D'Amour, "but I don't want to clean it", she had added quickly.

Death and inquest

In March 1992 Hancock died, aged 82 years, while living in the guesthouse of the Prix D'Amour, the palatial home he had built for his third wife, Rose. According to his daughter, the death was "unexpected" and came "despite strong will to live". An autopsy showed that he had died of arterioscleroticheart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, h ...

and police investigation revealed no evidence to contradict that. However, Hancock's daughter insisted that her stepmother had unnaturally hastened his death. Two successive state coroners refused to allow an inquest, but one was eventually granted in 1999 under the direction of the WA Attorney-General, Peter Foss.

After preliminary hearings during 2000, the inquest began in April 2001 with an initial estimate of 63 witnesses to be called over five weeks. The inquest was dominated by claims that Porteous had literally nagged Hancock to death with shrill tantrums and arguments. Porteous denied the allegations, famously explaining: "For anyone else it would be a tantrum, for me it's just raising my voice." In the last few days of Hancock's life, Porteous had attempted to pressure him into changing his will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and wi ...

and Hancock eventually took out a restraining order against her. The inquest was put on hold after allegations that Rinehart had paid witnesses to appear and that some had lied in their testimony. It resumed three months later with a smaller witness list and ended with the finding that Hancock had died of natural causes and not as a result of Porteous' behaviour.

With a legal bill of A$2.7m, Rose and William Porteous commenced action against Rinehart, that was eventually settled out of court in 2003.

Legacy

Hancock's daughter, Gina Rinehart, continues to chair Hancock Prospecting and its expansion into mining projects continues in Western Australia and other states of Australia, estimated to be earning about A$870 million in revenue in 2011. Rinehart is Australia's richest person and was also the world's richest woman for a period of time, with a net worth of 29.17 billion during 2012; by 2019, her wealth had eased to around $US14.8 billion, according to ''Forbes

''Forbes'' () is an American business magazine owned by Integrated Whale Media Investments and the Forbes family. Published eight times a year, it features articles on finance, industry, investing, and marketing topics. ''Forbes'' also r ...

''.

The Hancock Range, situated about north-west of the town of Newman

Newman is a surname of English origin and may refer to many people:

The surname Newman is widespread in the core Anglosphere.

A

* Abram Newman (1736–1799), British grocer

* Adrian Newman (disambiguation), multiple people

*Al Newman (born 196 ...

at , commemorates the family's contribution to the establishment of the pastoral and mining industry in the Pilbara region.

Bibliography

* * * * *References

External links

Hancock Prospecting website

ABC North-West WA, 8 July 2005.

Book review of Robert Wainwright's ''Rose''

from aussiereviews.com {{DEFAULTSORT:Hancock, Lang 1909 births 1992 deaths Volunteer Defence Corps soldiers People educated at Hale School People from Perth, Western Australia Pilbara Australian prospectors Lang Australian company founders Australian billionaires