Lydia Vandenburgh on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lydia ( Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient

Lydia ( Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient

The

The

The boundaries of historical Lydia varied across the centuries. It was bounded first by Mysia, Caria,

The boundaries of historical Lydia varied across the centuries. It was bounded first by Mysia, Caria,

In Greek myth, Lydia had also adopted the double-axe symbol, that also appears in the Mycenaean civilization, the '' labrys''. Omphale, daughter of the river Iardanos, was a ruler of Lydia, whom Heracles was required to serve for a time. His adventures in Lydia are the adventures of a Greek hero in a peripheral and foreign land: during his stay, Heracles enslaved the Itones; killed Syleus, who forced passers-by to hoe his vineyard; slew the serpent of the river Sangarios (which appears in the heavens as the constellation

In Greek myth, Lydia had also adopted the double-axe symbol, that also appears in the Mycenaean civilization, the '' labrys''. Omphale, daughter of the river Iardanos, was a ruler of Lydia, whom Heracles was required to serve for a time. His adventures in Lydia are the adventures of a Greek hero in a peripheral and foreign land: during his stay, Heracles enslaved the Itones; killed Syleus, who forced passers-by to hoe his vineyard; slew the serpent of the river Sangarios (which appears in the heavens as the constellation

According to Herodotus, the Lydians were the first people to use gold and silver coins and the first to establish retail shops in permanent locations. It is not known, however, whether Herodotus meant that the Lydians were the first to use coins of pure gold and pure silver or the first precious metal coins in general. Despite this ambiguity, this statement of Herodotus is one of the pieces of evidence most often cited on behalf of the argument that Lydians invented coinage, at least in the West, although the first coins (under Alyattes I, reigned c.591–c.560 BC) were neither gold nor silver but an alloy of the two called electrum.

The dating of these first stamped coins is one of the most frequently debated topics of ancient numismatics, with dates ranging from 700 BC to 550 BC, but the most common opinion is that they were minted at or near the beginning of the reign of King Alyattes (sometimes referred to incorrectly as Alyattes II). The first coins were made of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver that occurs naturally but that was further debased by the Lydians with added silver and copper.

The largest of these coins are commonly referred to as a 1/3 stater (''trite'') denomination, weighing around 4.7 grams, though no full staters of this type have ever been found, and the 1/3 stater probably should be referred to more correctly as a stater, after a type of a transversely held scale, the weights used in such a scale (from ancient Greek ίστημι=to stand), which also means "standard." These coins were stamped with a lion's head adorned with what is likely a sunburst, which was the king's symbol. The most prolific mint for early electrum coins was Sardis which produced large quantities of the lion head thirds, sixths and twelfths along with lion paw fractions. To complement the largest denomination, fractions were made, including a ''hekte'' (sixth), ''hemihekte'' (twelfth), and so forth down to a 96th, with the 1/96 stater weighing only about 0.15 grams. There is disagreement, however, over whether the fractions below the twelfth are actually Lydian.

Alyattes' son was

According to Herodotus, the Lydians were the first people to use gold and silver coins and the first to establish retail shops in permanent locations. It is not known, however, whether Herodotus meant that the Lydians were the first to use coins of pure gold and pure silver or the first precious metal coins in general. Despite this ambiguity, this statement of Herodotus is one of the pieces of evidence most often cited on behalf of the argument that Lydians invented coinage, at least in the West, although the first coins (under Alyattes I, reigned c.591–c.560 BC) were neither gold nor silver but an alloy of the two called electrum.

The dating of these first stamped coins is one of the most frequently debated topics of ancient numismatics, with dates ranging from 700 BC to 550 BC, but the most common opinion is that they were minted at or near the beginning of the reign of King Alyattes (sometimes referred to incorrectly as Alyattes II). The first coins were made of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver that occurs naturally but that was further debased by the Lydians with added silver and copper.

The largest of these coins are commonly referred to as a 1/3 stater (''trite'') denomination, weighing around 4.7 grams, though no full staters of this type have ever been found, and the 1/3 stater probably should be referred to more correctly as a stater, after a type of a transversely held scale, the weights used in such a scale (from ancient Greek ίστημι=to stand), which also means "standard." These coins were stamped with a lion's head adorned with what is likely a sunburst, which was the king's symbol. The most prolific mint for early electrum coins was Sardis which produced large quantities of the lion head thirds, sixths and twelfths along with lion paw fractions. To complement the largest denomination, fractions were made, including a ''hekte'' (sixth), ''hemihekte'' (twelfth), and so forth down to a 96th, with the 1/96 stater weighing only about 0.15 grams. There is disagreement, however, over whether the fractions below the twelfth are actually Lydian.

Alyattes' son was

Alyattes turned towards

Alyattes turned towards

Alyattes's eastern conquests brought the Lydian Empire in conflict in the 590s BCE with the Medes, and a war broke out between the Median and Lydian Empires in 590 BCE which was waged in eastern Anatolia lasted five years, until a Eclipse of Thales, solar eclipse occurred in 585 BCE during Battle of the Eclipse, a battle (hence called the Battle of the Eclipse) opposing the Lydian and Median armies, which both sides interpreted as an omen to end the war. The Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II and the king Syennesis of Cilicia acted as mediators in the ensuing peace treaty, which was sealed by the marriage of the Median king Cyaxares's son Astyages with Alyattes's daughter Aryenis, and the possible wedding of a daughter of Cyaxares with either Alyattes or with his son Croesus.

Alyattes's eastern conquests brought the Lydian Empire in conflict in the 590s BCE with the Medes, and a war broke out between the Median and Lydian Empires in 590 BCE which was waged in eastern Anatolia lasted five years, until a Eclipse of Thales, solar eclipse occurred in 585 BCE during Battle of the Eclipse, a battle (hence called the Battle of the Eclipse) opposing the Lydian and Median armies, which both sides interpreted as an omen to end the war. The Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II and the king Syennesis of Cilicia acted as mediators in the ensuing peace treaty, which was sealed by the marriage of the Median king Cyaxares's son Astyages with Alyattes's daughter Aryenis, and the possible wedding of a daughter of Cyaxares with either Alyattes or with his son Croesus.

In 547 BC, the Lydian king

In 547 BC, the Lydian king

When the Romans entered the capital Sardis in 133 BC, Lydia, as the other western parts of the Attalid legacy, became part of the

When the Romans entered the capital Sardis in 133 BC, Lydia, as the other western parts of the Attalid legacy, became part of the

Ancient episcopal sees of the late Roman province of Lydia are listed in the ''Annuario Pontificio'' as titular sees:''Annuario Pontificio 2013'' (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819–1013

Ancient episcopal sees of the late Roman province of Lydia are listed in the ''Annuario Pontificio'' as titular sees:''Annuario Pontificio 2013'' (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819–1013

Reid Goldsborough. "World's First Coin".

Livius.org: Lydia

{{Authority control Lydia, States and territories established in the 12th century BC States and territories disestablished in the 6th century BC Historical regions of Anatolia Ancient peoples History of Turkey Iron Age Anatolia Manisa Province History of İzmir Province Praetorian prefecture of the East Asia (Roman province) Iron Age countries in Asia Former monarchies of Western Asia

Lydia ( Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient

Lydia ( Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionian ...

in the modern western Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

provinces of Uşak, Manisa and inland Izmir. The ethnic group inhabiting this kingdom are known as the Lydians, and their language, known as Lydian, was a member of the Anatolian branch of the Indo-European language family. The capital of Lydia was Sardis.Rhodes, P.J. ''A History of the Classical Greek World 478–323 BC''. 2nd edition. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, p. 6.

The Kingdom of Lydia existed from about 1200 BC to 546 BC. At its greatest extent, during the 7th century BC, it covered all of western Anatolia. In 546 BC, it became a province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, known as the satrapy of Lydia or ''Sparda'' in Old Persian

Old Persian is one of the two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan language, Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native ...

. In 133 BC, it became part of the Roman province of Asia

The Asia ( grc, Ἀσία) was a Roman province covering most of western Anatolia, which was created following the Roman Republic's annexation of the Attalid Kingdom in 133 BC. After the establishment of the Roman Empire by Augustus, it was the ...

.

Lydian coins, made of silver, are among the oldest in existence, dated to around the 7th century BC.

Defining Lydia

The

The endonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

''Śfard'' (the name the Lydians called themselves) survives in bilingual and trilingual stone-carved notices of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

: the satrapy of ''Sparda'' (Old Persian

Old Persian is one of the two directly attested Old Iranian languages (the other being Avestan language, Avestan) and is the ancestor of Middle Persian (the language of Sasanian Empire). Like other Old Iranian languages, it was known to its native ...

), ''Saparda'', Babylonian ''Sapardu'', Elamitic

Elamite, also known as Hatamtite and formerly as Susian, is an extinct language that was spoken by the ancient Elamites. It was used in what is now southwestern Iran from 2600 BC to 330 BC. Elamite works disappear from the archeological record ...

''Išbarda'', Hebrew . These in the Greek tradition are associated with Sardis, the capital city of King Gyges Gyges can refer to:

* One of the Hecatoncheires from Greek mythology

* King Gyges of Lydia

* Ogyges

* Ring of Gyges

The Ring of Gyges ( grc, Γύγου Δακτύλιος, ''Gúgou Daktúlios'', ) is a hypothetical magic ring mentioned by the p ...

, constructed during the 7th century BC. Lydia is called ''Kisitan'' by Hayton of Corycus (in ''The Flower of the History of the East''), a name which was corrupted to ''Quesiton'' in '' The Travels of Sir John Mandeville''.

The region of the Lydian kingdom was during the 15th–14th centuries BCE part of the Arzawa kingdom. However, the Lydian language is usually not categorized as part of the Luwic subgroup, unlike the other nearby Anatolian languages Luwian, Carian, and Lycian.

Geography

Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires ...

and coastal Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionian ...

. Later, the military power of Alyattes and Croesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was ...

expanded Lydia, which, with its capital at Sardis, controlled all Asia Minor west of the River Halys, except Lycia. After the Persian conquest the River Maeander was regarded as its southern boundary, and during imperial Roman times Lydia comprised the country between Mysia and Caria on the one side and Phrygia and the Aegean Sea on the other.

Language

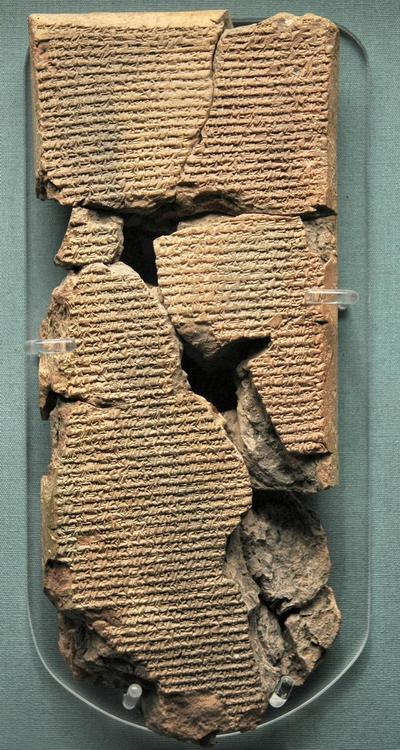

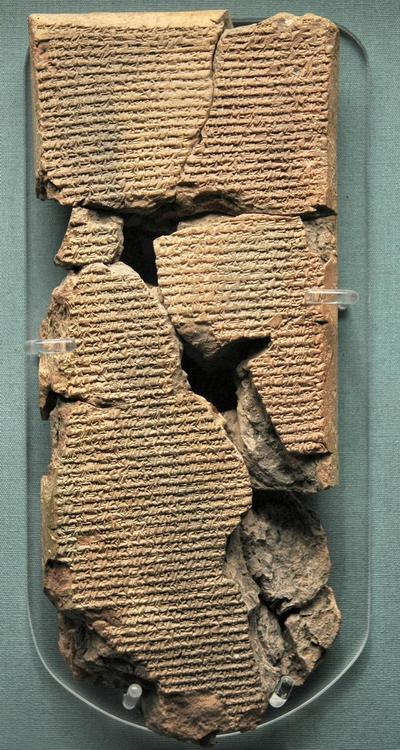

The Lydian language was anIndo-European language

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

in the Anatolian language family, related to Luwian and Hittite. Due to its fragmentary attestation, the meanings of many words are unknown but much of the grammar has been determined. Similar to other Anatolian languages, it featured extensive use of prefixes and grammatical particle

In grammar, the term ''particle'' (abbreviated ) has a traditional meaning, as a part of speech that cannot be inflected, and a modern meaning, as a function word associated with another word or phrase, generally in order to impart meaning. Altho ...

s to chain clauses together. Lydian had also undergone extensive syncope, leading to numerous consonant clusters atypical of Indo-European languages. Lydian finally became extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

during the 1st century BC.

History

Early history: Maeonia and Lydia

Lydia developed after the decline of the Hittite Empire in the 12th century BC. In Hittite times, the name for the region had been Arzawa. According to Greek source, the original name of the Lydian kingdom was ''Maionia'' (Μαιονία), or ''Maeonia'': Homer ('' Iliad'' ii. 865; v. 43, xi. 431) refers to the inhabitants of Lydia as ''Maiones'' (Μαίονες). Homer describes their capital not as Sardis but as ''Hyde'' (''Iliad'' xx. 385); Hyde may have been the name of the district in which Sardis was located. Later, Herodotus (''Histories

Histories or, in Latin, Historiae may refer to:

* the plural of history

* ''Histories'' (Herodotus), by Herodotus

* ''The Histories'', by Timaeus

* ''The Histories'' (Polybius), by Polybius

* ''Histories'' by Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust), ...

'' i. 7) adds that the "Meiones" were renamed Lydians after their king Lydus (Λυδός), son of Atys, during the mythical epoch that preceded the Heracleid dynasty. This etiological eponym served to account for the Greek ethnic name ''Lydoi'' (Λυδοί). The Hebrew term for Lydians, '' Lûḏîm'' (לודים), as found in the Book of Jeremiah

The Book of Jeremiah ( he, ספר יִרְמְיָהוּ) is the second of the Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible, and the second of the Prophets in the Christian Old Testament. The superscription at chapter Jeremiah 1:1–3 identifies the boo ...

(46.9), has been similarly considered, beginning with Flavius Josephus, to be derived from Lud son of Shem; however, Hippolytus of Rome (234 AD) offered an alternative opinion that the Lydians were descended from Ludim, son of Mizraim. During Biblical times, the Lydian warriors were famous archers. Some Maeones still existed during historical times in the upland interior along the River Hermus, where a town named Maeonia existed, according to Pliny the Elder (''Natural History'' book v:30) and Hierocles (author of Synecdemus).

In Greek mythology

Lydian mythology is virtually unknown, and their literature and rituals have been lost due to the absence of any monuments or archaeological finds with extensive inscriptions; therefore, myths involving Lydia are mainly from Greek mythology. For the Greeks, Tantalus was a primordial ruler of mythic Lydia, and Niobe his proud daughter; her husband Amphion associated Lydia with Thebes in Greece, and through Pelops the line of Tantalus was part of the founding myths of Mycenae's second dynasty. (In reference to the myth ofBellerophon

Bellerophon (; Ancient Greek: Βελλεροφῶν) or Bellerophontes (), born as Hipponous, was a hero of Greek mythology. He was "the greatest hero and slayer of monsters, alongside Cadmus and Perseus, before the days of Heracles", and his ...

, Karl Kerenyi remarked, in ''The Heroes of The Greeks'' 1959, p. 83. "As Lykia

Lycia ( Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; el, Λυκία, ; tr, Likya) was a state or nationality that flourished in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is t ...

was thus connected with Crete, and as the person of Pelops, the hero of Olympia, connected Lydia with the Peloponnesos, so Bellerophontes connected another Asian country, or rather two, Lykia and Karia

Karia is a settlement in Kenya

)

, national_anthem = " Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, ...

, with the kingdom of Argos".)

In Greek myth, Lydia had also adopted the double-axe symbol, that also appears in the Mycenaean civilization, the '' labrys''. Omphale, daughter of the river Iardanos, was a ruler of Lydia, whom Heracles was required to serve for a time. His adventures in Lydia are the adventures of a Greek hero in a peripheral and foreign land: during his stay, Heracles enslaved the Itones; killed Syleus, who forced passers-by to hoe his vineyard; slew the serpent of the river Sangarios (which appears in the heavens as the constellation

In Greek myth, Lydia had also adopted the double-axe symbol, that also appears in the Mycenaean civilization, the '' labrys''. Omphale, daughter of the river Iardanos, was a ruler of Lydia, whom Heracles was required to serve for a time. His adventures in Lydia are the adventures of a Greek hero in a peripheral and foreign land: during his stay, Heracles enslaved the Itones; killed Syleus, who forced passers-by to hoe his vineyard; slew the serpent of the river Sangarios (which appears in the heavens as the constellation Ophiucus

Ophiuchus () is a large constellation straddling the celestial equator. Its name comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning "serpent-bearer", and it is commonly represented as a man grasping a snake. The serpent is represented by the constellat ...

) and captured the simian tricksters, the Cercopes. Accounts tell of at least one son of Heracles who was born to either Omphale or a slave-girl: Herodotus (''Histories'' i. 7) says this was Alcaeus who began the line of Lydian Heracleidae which ended with the death of Candaules c. 687 BC. Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

(4.31.8) and Ovid (''Heroides'' 9.54) mentions a son called Lamos, while pseudo-Apollodorus (''Bibliotheke

Bibliotheca may refer to:

* ''Bibliotheca'' (Pseudo-Apollodorus), a grand summary of traditional Greek mythology and heroic legends

* '' Bibliotheca historica'', a first century BC work of universal history by Diodorus Siculus

* ''Bibliotheca'' ...

'' 2.7.8) gives the name Agelaus and Pausanias (2.21.3) names Tyrsenus as the son of Heracles by "the Lydian woman". All three heroic ancestors indicate a Lydian dynasty claiming Heracles as their ancestor. Herodotus (1.7) refers to a Heraclid dynasty of kings who ruled Lydia, yet were perhaps not descended from Omphale. He also mentions (1.94) the legend that the Etruscan civilization was founded by colonists from Lydia led by Tyrrhenus

In Etruscan mythology, Tyrrhenus (in el, Τυῤῥηνός) was one of the founders of the Etruscan League of twelve cities, along with his brother Tarchon. Herodotus describes him as the saviour of the Etruscans, because he led them from Lydia t ...

, brother of Lydus. Dionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus ( grc, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary sty ...

was skeptical of this story, indicating that the Etruscan language and customs were known to be totally dissimilar to those of the Lydians. In addition, the story of the "Lydian" origins of the Etruscans was not known to Xanthus of Lydia, an authority on the history of the Lydians.

Later chronologists ignored Herodotus' statement that Agron of Lydia, Agron was the first Heraclid to be a king, and included his immediate forefathers Alcaeus, Belus, and Ninus in their list of kings of Lydia. Strabo (5.2.2) has Atys, father of Lydus and Tyrrhenus, as a descendant of Heracles and Omphale but that contradicts virtually all other accounts which name Atys, Lydus, and Tyrrhenus among the pre-Heraclid kings and princes of Lydia. The gold deposits in the river Pactolus that were the source of the proverbial wealth of Croesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was ...

(Lydia's last king) were said to have been left there when the legendary king Midas of Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires ...

washed away the "Midas touch" in its waters.

In Euripides' tragedy ''The Bacchae'', Dionysus, while maintaining his human disguise, declares his country to be Lydia.

Lydians, the Tyrrhenians and the Etruscans

The relationship between the Etruscans of northern and central Italy and the Lydians has long been a subject of conjecture. While the Greek historian Herodotus stated that the Etruscans originated in Lydia, the 1st-century BC historianDionysius of Halicarnassus

Dionysius of Halicarnassus ( grc, Διονύσιος Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἁλικαρνασσεύς,

; – after 7 BC) was a Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric, who flourished during the reign of Emperor Augustus. His literary sty ...

, a Greek living in Rome, dismissed many of the ancient theories of other Greek historians and postulated that the Etruscans were indigenous people who had always lived in Etruria in Italy and were different from both the Pelasgians and the Lydians. Dionysius noted that the 5th-century historian Xanthus of Lydia, who was originally from Sardis and was regarded as an important source and authority for the history of Lydia, never suggested a Lydian origin of the Etruscans and never named Tyrrhenus as a ruler of the Lydians.

In modern times, all the evidence gathered so far by etruscologists points to an indigenous origin of the Etruscans. The classical scholar Michael Grant (author), Michael Grant commented on Herodotus' story, writing that it "is based on erroneous etymologies, like many other traditions about the origins of 'fringe' peoples of the Greek world". Grant writes there is evidence that the Etruscans themselves spread it to make their trading easier in Asia Minor when many cities in Asia Minor, and the Etruscans themselves, were at war with the Greeks. The French scholar Dominique Briquel also disputed the historical validity of Herodotus' text. Briquel demonstrated that "the story of an exodus from Lydia to Italy was a deliberate political fabrication created in the Hellenized milieu of the court at Sardis in the early 6th century BC." Briquel also commented that "the traditions handed down from the Greek authors on the origins of the Etruscan people are only the expression of the image that Etruscans' allies or adversaries wanted to divulge. For no reason, stories of this kind should be considered historical documents".

Archaeologically there is no evidence for a migration of the Lydians into Etruria. The most ancient phase of the Etruscan civilization is the Villanovan culture, which begins around 900 BC, which itself developed from the previous late Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture in the same region in Italy in the last quarter of the second millennium BC, which in turn derives from the Urnfield culture of Central Europe and has no relation with Asia Minor, and there is nothing about it that suggests an ethnic contribution from Asia Minor or the Near East or that can support a migration theory.

Linguists have identified an Lemnian language, Etruscan-like language in a Lemnos stele, set of inscriptions on the island of Lemnos, in the Aegean Sea. Since the Etruscan language was a Paleo-European languages#Paleo-European languages of Italy, Pre-Indo-European language and neither Indo-European or Semitic, Etruscan was not related to Lydian, which was a part of the Anatolian language, Anatolian branch of the Indo-European languages. Instead, Etruscan language and the Lemnian language are considered part of the pre-Indo-European Tyrrhenian language family together with the Rhaetian language of the Alps, which takes its name from the Rhaetian people.

A 2013 genetic study suggested that the maternal lineages – as reflected in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) – of western Anatolians, and the modern population of Tuscany had been largely separate for 5,000 to 10,000 years (with a 95% credible interval); the mtDNA of Etruscans was most similar to modern Tuscans and Neolithic populations from Central Europe. This was interpreted as suggesting that the Etruscan population were descended from the Villanovan culture. The study concluded that the Etruscans were indigenous, and that a link between Etruria, modern Tuscany and Lydia dates back to the Neolithic Europe, Neolithic period, at the time of the migrations of Early European Farmers from Anatolia to Europe.

A 2019 genetic study published in the journal ''Science (journal), Science'' analyzed the autosomal DNA of 11 Iron Age samples from the areas around Rome concluding that Etruscans (900–600 BC) and the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins (900–500 BC) from Latium vetus were genetically similar. Their DNA was a mixture of two-thirds Copper Age ancestry (Early European Farmers, EEF + Western Hunter-Gatherer, WHG; Etruscans ~66–72%, Latins ~62–75%) and one-third Steppe-related ancestry (Etruscans ~27–33%, Latins ~24–37%). The results of this study once again suggested that the Etruscans were indigenous, and that the Etruscans also had Steppe-related ancestry despite continuing to speak a pre-Indo-European language.

First coinage

According to Herodotus, the Lydians were the first people to use gold and silver coins and the first to establish retail shops in permanent locations. It is not known, however, whether Herodotus meant that the Lydians were the first to use coins of pure gold and pure silver or the first precious metal coins in general. Despite this ambiguity, this statement of Herodotus is one of the pieces of evidence most often cited on behalf of the argument that Lydians invented coinage, at least in the West, although the first coins (under Alyattes I, reigned c.591–c.560 BC) were neither gold nor silver but an alloy of the two called electrum.

The dating of these first stamped coins is one of the most frequently debated topics of ancient numismatics, with dates ranging from 700 BC to 550 BC, but the most common opinion is that they were minted at or near the beginning of the reign of King Alyattes (sometimes referred to incorrectly as Alyattes II). The first coins were made of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver that occurs naturally but that was further debased by the Lydians with added silver and copper.

The largest of these coins are commonly referred to as a 1/3 stater (''trite'') denomination, weighing around 4.7 grams, though no full staters of this type have ever been found, and the 1/3 stater probably should be referred to more correctly as a stater, after a type of a transversely held scale, the weights used in such a scale (from ancient Greek ίστημι=to stand), which also means "standard." These coins were stamped with a lion's head adorned with what is likely a sunburst, which was the king's symbol. The most prolific mint for early electrum coins was Sardis which produced large quantities of the lion head thirds, sixths and twelfths along with lion paw fractions. To complement the largest denomination, fractions were made, including a ''hekte'' (sixth), ''hemihekte'' (twelfth), and so forth down to a 96th, with the 1/96 stater weighing only about 0.15 grams. There is disagreement, however, over whether the fractions below the twelfth are actually Lydian.

Alyattes' son was

According to Herodotus, the Lydians were the first people to use gold and silver coins and the first to establish retail shops in permanent locations. It is not known, however, whether Herodotus meant that the Lydians were the first to use coins of pure gold and pure silver or the first precious metal coins in general. Despite this ambiguity, this statement of Herodotus is one of the pieces of evidence most often cited on behalf of the argument that Lydians invented coinage, at least in the West, although the first coins (under Alyattes I, reigned c.591–c.560 BC) were neither gold nor silver but an alloy of the two called electrum.

The dating of these first stamped coins is one of the most frequently debated topics of ancient numismatics, with dates ranging from 700 BC to 550 BC, but the most common opinion is that they were minted at or near the beginning of the reign of King Alyattes (sometimes referred to incorrectly as Alyattes II). The first coins were made of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver that occurs naturally but that was further debased by the Lydians with added silver and copper.

The largest of these coins are commonly referred to as a 1/3 stater (''trite'') denomination, weighing around 4.7 grams, though no full staters of this type have ever been found, and the 1/3 stater probably should be referred to more correctly as a stater, after a type of a transversely held scale, the weights used in such a scale (from ancient Greek ίστημι=to stand), which also means "standard." These coins were stamped with a lion's head adorned with what is likely a sunburst, which was the king's symbol. The most prolific mint for early electrum coins was Sardis which produced large quantities of the lion head thirds, sixths and twelfths along with lion paw fractions. To complement the largest denomination, fractions were made, including a ''hekte'' (sixth), ''hemihekte'' (twelfth), and so forth down to a 96th, with the 1/96 stater weighing only about 0.15 grams. There is disagreement, however, over whether the fractions below the twelfth are actually Lydian.

Alyattes' son was Croesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was ...

(Reigned c.560–c.546 BC), who became associated with great wealth. Croesus is credited with issuing the ''Croeseid'', the first true gold coins with a standardised purity for general circulation, and the world's first bimetallism, bimetallic monetary system circa 550 BCE.

It took some time before ancient coins were used for commerce and trade. Even the smallest-denomination electrum coins, perhaps worth about a day's subsistence, would have been too valuable for buying a loaf of bread. The first coins to be used for retailing on a large-scale basis were likely small silver fractions, Hemiobol, Ancient Greek coinage minted in Cyme (Aeolis) under Hermodike II then by the Ionians, Ionian Greeks in the late sixth century BC.

Sardis was renowned as a beautiful city. Around 550 BC, near the beginning of his reign, Croesus paid for the construction of the temple of Artemis at Ephesus, which became one of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. Croesus was defeated in battle by Cyrus the Great, Cyrus II Achaemenid Empire, of Persia in 546 BC, with the Lydian kingdom losing its autonomy and becoming a Persian satrapy.

Autochthonous dynasties

According to Herodotus, Lydia was ruled by three dynasties from the second millennium BC to 546 BC. The first two dynasties are legendary and the third is historical. Herodotus mentions three early Maeonian kings: Manes of Lydia, Manes, his son Atys and his grandson Lydus. Lydus gave his name to the country and its people. One of his descendants was Iardanus of Lydia, Iardanus, with whom Heracles was in service at one time. Heracles had an affair with one of Iardanus' slave-girls and their son Alcaeus was the first of the Lydian Heraclids. The Maeonians relinquished control to the Heracleidae and Herodotus says they ruled through 22 generations for a total of 505 years from c. 1192 BC. The first Heraclid king was Agron of Lydia, Agron, the great-grandson of Alcaeus. He was succeeded by 19 Heraclid kings, names unknown, all succeeding father to son. In the 8th century BC, Meles of Lydia, Meles became the 21st and penultimate Heraclid king and the last was his son Candaules (died c. 687 BC).The Mermnad Empire

=Gyges

= Available historical evidence suggests that Candaules was overthrown by a man named Gyges, of whose origins nothing is known except for the Greek historian Herodotus's claim that he was the son of a man named Dascylus. Gyges was helped in his coup against Candaules by a Carian prince from Milas, Mylasa named Arselis, suggesting that Gyges's Mermnad dynasty might have had good relations with Carian aristocrats thanks to which these latter would provide his rebellion with armed support against Candaules. Gyges's rise to power happened in the context of a period of turmoil following the invasion of the Cimmerians, a nomadic people from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, Pontic steppe who had invaded Western Asia, who around 675 BCE destroyed the previous major power in Anatolia, the kingdom of Phrygia. Gyges took advantage of the power vacuum created by the Cimmerian invasions to consolidate his kingdom and make it a military power, he contacted the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Neo-Assyrian court by sending diplomats to Nineveh to seek help against the Cimmerian invasions, and he attacked the Ionians, Ionian Greek cities of Miletus, Smyrna, and Colophon (city), Colophon. Gyges's extensive alliances with the Carian dynasts allowed him to recruit Carian and Ionian Greek soldiers to send overseas to assist the Ancient Egypt, Egyptian king Psamtik I of the city of Sais, with whom he had established contacts around 662 BCE. With the help of these armed forces, Psamtik I united Egypt under his rule after eliminating the eleven other kinglets with whom he had been co-ruling Lower Egypt. In 644 BCE, Lydia faced a third attack by the Cimmerians, led by their king Tugdamme, Lygdamis. This time, the Lydians were defeated, Sardis was sacked, and Gyges was killed.=Ardys and Sadyattes

= Gyges was succeeded by his son Ardys of Lydia, Ardys, who resumed diplomatic activity with Assyria and would also have to face the Cimmerians. Ardys attacked the Ionians, Ionian Greek city of Miletus and succeeded in capturing the city of Priene, after which Priene would remain under direct rule of the Lydian kingdom until its end. Ardys's reign was short-lived, and in 637 BCE, that is in Ardys's seventh regnal year, the Thracians, Thracian Treri, Treres tribe who had migrated across the Bosporus, Thracian Bosporus and invaded Anatolia, under their king Kobos, and in alliance with the Cimmerians and the Lycians, attacked Lydia. They defeated the Lydians again and for a second time sacked the Lydian capital of Sardis, except for its citadel. It is probable that Ardys was killed during this Cimmerian attack. Ardys was succeeded by his son, Sadyattes, who had an even more short-lived reign. Sadyattes died in 635 BCE, and it is possible that, like his grandfather Gyges and maybe his father Ardys as well, he died fighting the Cimmerians.=Alyattes

= Amidst extreme turmoil, Sadyattes was succeeded in 635 BCE by his son Alyattes, who would transform Lydia into a powerful empire. Soon after Alyattes's ascension and early during his reign, with Neo-Assyrian Empire, Assyrian approval and in alliance with the Lydians, the Scythians under their king Madyes entered Anatolia, expelled the Treres from Asia Minor, and defeated the Cimmerians so that they no longer constituted a threat again, following which the Scythians extended their domination to Central Anatolia until they were themselves expelled by the Medes from Western Asia in the 590s BCE. This final defeat of the Cimmerians was carried out by the joint forces of Madyes, who Strabo credits with expelling the Cimmerians from Asia Minor, and of Alyattes, whom Herodotus and Polyaenus claim finally defeated the Cimmerians. Alyattes turned towards

Alyattes turned towards Phrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires ...

in the east, where extended Lydian rule eastwards to Phrygia. Alyattes continued his expansionist policy in the east, and of all the peoples to the west of the Halys River whom Herodotus claimed Alyattes's successor Croesus ruled over - the Lydians, Phrygians, Mysians, Mariandyni, Chalybes, Paphlagonians, Thyni and Bithyni Thracians, Carians, Ionians, Doric Hexapolis, Dorians, Aeolis, Aeolians, and Pamphylians - it is very likely that a number of these populations had already been conquered under Alyattes, and it is not impossible that the Lydians might have subjected Lycia, given that the Lycian coast would have been important for the Lydians because it was close to a trade route connecting the Aegean Sea, Aegean region, the Levant, and Cyprus.

Alyattes's eastern conquests brought the Lydian Empire in conflict in the 590s BCE with the Medes, and a war broke out between the Median and Lydian Empires in 590 BCE which was waged in eastern Anatolia lasted five years, until a Eclipse of Thales, solar eclipse occurred in 585 BCE during Battle of the Eclipse, a battle (hence called the Battle of the Eclipse) opposing the Lydian and Median armies, which both sides interpreted as an omen to end the war. The Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II and the king Syennesis of Cilicia acted as mediators in the ensuing peace treaty, which was sealed by the marriage of the Median king Cyaxares's son Astyages with Alyattes's daughter Aryenis, and the possible wedding of a daughter of Cyaxares with either Alyattes or with his son Croesus.

Alyattes's eastern conquests brought the Lydian Empire in conflict in the 590s BCE with the Medes, and a war broke out between the Median and Lydian Empires in 590 BCE which was waged in eastern Anatolia lasted five years, until a Eclipse of Thales, solar eclipse occurred in 585 BCE during Battle of the Eclipse, a battle (hence called the Battle of the Eclipse) opposing the Lydian and Median armies, which both sides interpreted as an omen to end the war. The Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II and the king Syennesis of Cilicia acted as mediators in the ensuing peace treaty, which was sealed by the marriage of the Median king Cyaxares's son Astyages with Alyattes's daughter Aryenis, and the possible wedding of a daughter of Cyaxares with either Alyattes or with his son Croesus.

=Croesus

= Alyattes died shortly after the Battle of the Eclipse, in 585 BCE itself, following which Lydia faced a power struggle between his son Pantaleon, born from a Greek woman, and his other sonCroesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was ...

, born from a Carian noblewoman, out of which the latter emerged successful.

Croesus brought Caria under the direct control of the Lydian Empire, and he subjugated all of mainland Ionia

Ionia () was an ancient region on the western coast of Anatolia, to the south of present-day Izmir. It consisted of the northernmost territories of the Ionian League of Greek settlements. Never a unified state, it was named after the Ionian ...

, Aeolis, and Doric Hexapolis, Doris, but he abandoned his plans of annexing the Greek city-states on the islands of the Aegean Sea and he instead concluded treaties of friendship with them, which might have helped him participate in the lucrative trade the Aegean Greeks carried out with Egypt at Naucratis. According to Herodotus, Croesus ruled over all the peoples to the west of the Halys River, although the actual border of his kingdom was further to the east of the Halys, at an undetermined point in eastern Anatolia.

Croesus continued the friendly relations with the Medes concluded between his father Alyattes and the Median king Cyaxares, and he continued these good relations with the Medes after he succeeded Alyattes and Astyages succeeded Cyaxares. And, under Croesus's rule, Lydia continued its good relations started by Gyges with the Sais, Egypt, Saite Egyptian kingdom, then ruled by the Pharaoh, pharaoh Amasis II. Croesus also established trade and diplomatic relations with the Neo-Babylonian Empire of Nabonidus, and he further increased his contacts with the Greeks on the European continent by establishing relations with the city-state of Sparta.

In 550 BCE, Croesus's brother-in-law, the Median king Astyages, was overthrown by his own grandson, the Persian king Cyrus the Great, and Croesus responded by attacking Pteria (Cappadocia), Pteria, the capital of a Phrygian state vassal to the Lydians which might have attempted to declare its allegiance to the new Persian Empire of Cyrus. Cyrus retaliated by intervening in Cappadocia and defeating the Lydians at Pteria in a Battle of Pteria, battle, and again Battle of Thymbra, at Thymbra before Siege of Sardis (547 BC), besieging and capturing the Lydian capital of Sardis, thus bringing an end to the rule of the Mermnad dynasty and to the Lydian Empire. Lydia would never regain its independence and would remain a part of various successive empires.

Although the dates for the battles of Pteria and Thymbra and of end of the Lydian empire have been traditionally fixed to 547 BCE, more recent estimates suggest that Herodotus's account being unreliable chronologically concerning the fall of Lydia means that there are currently no ways of dating the end of the Lydian kingdom; theoretically, it may even have taken place after the fall of Babylon in 539 BC.

Persian Empire

In 547 BC, the Lydian king

In 547 BC, the Lydian king Croesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was ...

besieged and captured the Persian city of Pteria (Turkey), Pteria in Cappadocia and enslaved its inhabitants. The Persian king Cyrus The Great marched with his army against the Lydians. The Battle of Pteria resulted in a stalemate, forcing the Lydians to retreat to their capital city of Sardis. Some months later the Persian and Lydian kings met at the Battle of Thymbra. Cyrus won and captured the capital city of Sardis by 546 BC. Lydia became a province ( satrapy) of the Persian Empire.

Hellenistic Empire

Lydia remained a satrapy after Persia's conquest by the Macedonian king Alexander the Great, Alexander III (the Great) of Macedon. When Alexander's empire ended after his death, Lydia was possessed by the major Asian diadoch dynasty, the Seleucids, and when it was unable to maintain its territory in Asia Minor, Lydia was acquired by the Attalid dynasty of Pergamum. Its last king avoided the spoils and ravage of a Roman war of conquest by leaving the realm by testament to the Roman Empire.Roman province of Asia

When the Romans entered the capital Sardis in 133 BC, Lydia, as the other western parts of the Attalid legacy, became part of the

When the Romans entered the capital Sardis in 133 BC, Lydia, as the other western parts of the Attalid legacy, became part of the province of Asia

The Asia ( grc, Ἀσία) was a Roman province covering most of western Anatolia, which was created following the Roman Republic's annexation of the Attalid Kingdom in 133 BC. After the establishment of the Roman Empire by Augustus, it was the ...

, a very rich Roman province, worthy of a governor with the high rank of proconsul. The whole west of Asia Minor had Jewish colonies very early, and Christianity was also soon present there. Acts of the Apostles 16:14–15 mentions the baptism of a merchant woman called "Lydia" from Thyatira, known as Lydia of Thyatira, in what had once been the satrapy of Lydia. Christianity spread rapidly during the 3rd century AD, based on the nearby Exarchate of Ephesus.

Roman province of Lydia

Under the tetrarchy reform of Emperor Diocletian in 296 AD, Lydia was revived as the name of a separate Roman province, much smaller than the former satrapy, with its capital at Sardis. Together with the provinces of Caria, Hellespontus (province), Hellespontus, Lycia, Pamphylia, Phrygia prima and Phrygia secunda, Pisidia (all in modern Turkey) and the Insulae (Ionian islands, mostly in modern Greece), it formed the diocese (under a ''vicarius'') of Asia (Roman province), Asiana, which was part of the praetorian prefecture of Oriens, together with the dioceses Pontiana (most of the rest of Asia Minor), Oriens proper (mainly Syria), Aegyptus (Egypt) and Thraciae (on the Balkans, roughly Bulgaria).Byzantine (and Crusader) age

Under the Byzantine emperor Heraclius (610–641), Lydia became part of Anatolikon, one of the original ''Theme (Byzantine administrative unit), themata'', and later of Thrakesion. Although the Seljuk Turks conquered most of the rest of Anatolia, forming the Sultanate of Ikonion (Konya), Lydia remained part of the Byzantine Empire. While the Venetians occupied Constantinople and Greece as a result of the Fourth Crusade, Lydia continued as a part of the Byzantine rump state called the Empire of Nicaea, Nicene Empire based at İznik, Nicaea until 1261.Under Turkish rule

Lydia was captured finally by Turkish ''Anatolian Turkish Beyliks, beyliks'', which were all absorbed by the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman state in 1390. The area became part of the Ottoman Aidin Vilayet (''province''), and is now in the modern republic of Turkey.Christianity

Lydia had numerous Christian communities and, after Christianity became the State religion, official religion of the Roman Empire in the 4th century, Lydia became one of the provinces of the diocese of Asia in the Patriarchate of Constantinople. The ecclesiastical province of Lydia had a metropolitan diocese at Sardis and suffragan dioceses for Alaşehir, Philadelphia, Thyatira, Tripolis (Phrygia), Tripolis, Settae, Gordus (Lydia), Gordus, Tralles, Silandus, Maeonia (city), Maeonia, Apollonos Hierum, Mostene, Apollonias, Attalia, Hyrcania, Bage, Balandus, Hermocapella, Hierocaesarea, Acrassus, Dalda, Stratonicia, Cerasa, Jabala, Gabala, Satala, Aureliopolis and Hellenopolis. Bishops from the various dioceses of Lydia were well represented at the Council of Nicaea in 325 and at the later ecumenical councils.Episcopal sees

Ancient episcopal sees of the late Roman province of Lydia are listed in the ''Annuario Pontificio'' as titular sees:''Annuario Pontificio 2013'' (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819–1013

Ancient episcopal sees of the late Roman province of Lydia are listed in the ''Annuario Pontificio'' as titular sees:''Annuario Pontificio 2013'' (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819–1013

See also

* Ancient regions of Anatolia * Digda * List of Kings of Lydia * List of satraps of Lydia * LudimReferences

Sources

* * * * * * * *Further reading

Reid Goldsborough. "World's First Coin".

External links

*Livius.org: Lydia

{{Authority control Lydia, States and territories established in the 12th century BC States and territories disestablished in the 6th century BC Historical regions of Anatolia Ancient peoples History of Turkey Iron Age Anatolia Manisa Province History of İzmir Province Praetorian prefecture of the East Asia (Roman province) Iron Age countries in Asia Former monarchies of Western Asia