Lumières Awards 2015 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Lumières (literally in English: ''The Lights'') was a cultural, philosophical, literary and intellectual movement beginning in the second half of the 17th century, originating in France, then

The Lumières (literally in English: ''The Lights'') was a cultural, philosophical, literary and intellectual movement beginning in the second half of the 17th century, originating in France, then

The Lumières movement was in large part an extension of the discoveries of

The Lumières movement was in large part an extension of the discoveries of

The ideal figure of the Lumières was a philosopher, a

The ideal figure of the Lumières was a philosopher, a

The

The

The Lumières (literally in English: ''The Lights'') was a cultural, philosophical, literary and intellectual movement beginning in the second half of the 17th century, originating in France, then

The Lumières (literally in English: ''The Lights'') was a cultural, philosophical, literary and intellectual movement beginning in the second half of the 17th century, originating in France, then western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

and spreading throughout the rest of Europe. It included philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

, John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

, Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English essayist, historian, and politician. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, is known for ...

, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

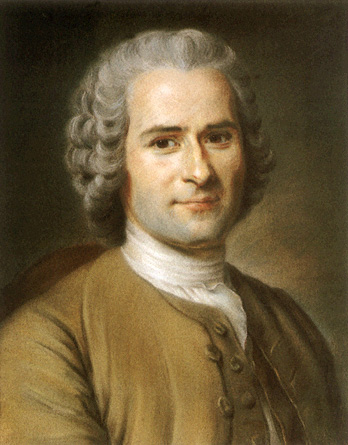

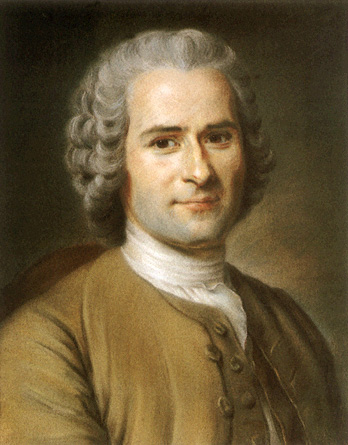

, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

, Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

, Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle (; 18 November 1647 – 28 December 1706) was a French philosopher, author, and lexicographer. He is best known for his '' Historical and Critical Dictionary'', whose publication began in 1697. Many of the more controversial ideas ...

and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

. This movement is influenced by the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

in southern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

arising directly from the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( ) was a period in History of Italy, Italian history between the 14th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Western Europe and marked t ...

with people like Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

. Over time it came to mean the , in English the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

.

Members of the movement saw themselves as a progressive élite, and battled against religious and political persecution, fighting against what they saw as the irrationality, arbitrariness, obscurantism

In philosophy, obscurantism or obscurationism is the Anti-intellectualism, anti-intellectual practice of deliberately presenting information in an wikt:abstruse, abstruse and imprecise manner that limits further inquiry and understanding of a subj ...

and superstition of the previous centuries. They redefined the study of knowledge to fit the ethics and aesthetics of their time. Their works had great influence at the end of the 18th century, in the American Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America in the original printing, is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the Second Continen ...

and the French Revolution.

This intellectual and cultural renewal by the Lumières movement was, in its strictest sense, limited to Europe. These ideas were well understood in Europe, but beyond France the idea of "enlightenment" had generally meant a light from outside, whereas in France it meant a light coming from knowledge one gained.

In the most general terms, in science and philosophy, the Enlightenment aimed for the triumph of reason over faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

and belief

A belief is a subjective Attitude (psychology), attitude that something is truth, true or a State of affairs (philosophy), state of affairs is the case. A subjective attitude is a mental state of having some Life stance, stance, take, or opinion ...

; in politics and economics, the triumph of the bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

over nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

and clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

.

Philosophical themes

Scientific Revolution

Advances in scientific method

The Lumières movement was in large part an extension of the discoveries of

The Lumières movement was in large part an extension of the discoveries of Nicolas Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a model of the universe that placed the Sun rather than Earth at its center. Copernicus likely developed his model independently of Aris ...

in the 16th century, which were not well known during his lifetime, and more so of the theories of Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

(1564 – 1642). Inquiries to establish certain axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

s and mathematical proof

A mathematical proof is a deductive reasoning, deductive Argument-deduction-proof distinctions, argument for a Proposition, mathematical statement, showing that the stated assumptions logically guarantee the conclusion. The argument may use othe ...

s continued as Cartesianism

Cartesianism is the philosophical and scientific system of René Descartes and its subsequent development by other seventeenth century thinkers, most notably François Poullain de la Barre, Nicolas Malebranche and Baruch Spinoza. Descartes i ...

throughout the 17th century.

Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (or Leibnitz; – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to many ...

(1646 – 1716) and Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

(1642 – 1727) had independently and almost simultaneously developed the calculus

Calculus is the mathematics, mathematical study of continuous change, in the same way that geometry is the study of shape, and algebra is the study of generalizations of arithmetic operations.

Originally called infinitesimal calculus or "the ...

, and René Descartes

René Descartes ( , ; ; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and Modern science, science. Mathematics was paramou ...

(1596 – 1650) the idea of monads. British philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

and David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

adopted an approach, later called empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

, which preferred the use of the senses

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditionally identified as su ...

and experience

Experience refers to Consciousness, conscious events in general, more specifically to perceptions, or to the practical knowledge and familiarity that is produced by these processes. Understood as a conscious event in the widest sense, experience i ...

over that of pure reason

The modern division of philosophy into theoretical philosophy and practical philosophyImmanuel Kant, ''Lectures on Ethics'', Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 41 ("On Universal Practical Philosophy"). Original text: Immanuel Kant, ''Kant’s G ...

.

Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (24 November 163221 February 1677), also known under his Latinized pen name Benedictus de Spinoza, was a philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, who was born in the Dutch Republic. A forerunner of the Age of Enlightenmen ...

took Descartes' side, most of all in his ''Ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

''. But he demurred from Descartes in ("On the Improvement of the Understanding"), where he argued that the process of perception

Perception () is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment. All perception involves signals that go through the nervous syste ...

is not one of pure reason, but also the senses and intuition

Intuition is the ability to acquire knowledge without recourse to conscious reasoning or needing an explanation. Different fields use the word "intuition" in very different ways, including but not limited to: direct access to unconscious knowledg ...

. Spinoza's thought was based on a model of the universe where God and Nature are one and the same. This became an anchor in the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

, held across the ages from Newton's time to that of Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

's (1743–1826).

A notable change was the emergence of a naturalist philosophy, spreading across Europe, embodied by Newton. The scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

– exploring experimental evidence and constructing consistent theories and axiom systems from observed phenomena – was undeniably useful. The predictive ability of its resulting theories set the tone for his masterwork ''Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, value, mind, and language. It is a rational and critical inquiry that reflects on ...

'' (1687). As an example of scientific progress in the Age of Reason

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empiric ...

and the Lumières movement, Newton's example remains unsurpassed, in taking observed facts and constructing a theory which explains them a priori

('from the earlier') and ('from the later') are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, Justification (epistemology), justification, or argument by their reliance on experience. knowledge is independent from any ...

, for example taking the motions of the planets observed by Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best know ...

to confirm his law of universal gravitation. Naturalism saw the unification of pure empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

as practiced by the likes of Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued for the importance of nat ...

with the axiomatic, "pure reason" approach of Descartes.

Belief in an intelligible world ordered by a Christian God became the crux of philosophical investigations of knowledge. On one side, religious philosophy concentrated on piety

Piety is a virtue which may include religious devotion or spirituality. A common element in most conceptions of piety is a duty of respect. In a religious context, piety may be expressed through pious activities or devotions, which may vary amon ...

, and the omniscience and ultimately mysterious nature of God; on the other were ideas such as deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

, underpinned by the impression that the world was comprehensible by human reason and that it was governed by universal physical laws. God was imagined as a "Great Watchmaker"; experimental natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

s found the world to be more and more ordered, even as machines and measuring instruments became ever more sophisticated and precise.

The most famous French natural philosopher of the 18th century, Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French Natural history, naturalist, mathematician, and cosmology, cosmologist. He held the position of ''intendant'' (director) at the ''Jardin du Roi'', now ca ...

, was critical of this natural theology in his masterwork ''Histoire Naturelle

The ''Histoire Naturelle, générale et particulière, avec la description du Cabinet du Roi'' (; ) is an encyclopaedic collection of 36 large (quarto) volumes written between 1749–1804, initially by the Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, Comte ...

''. Buffon rejected the idea of ascribing to divine intervention

Divine intervention is an event that occurs when a deity (i.e. God or gods) becomes actively involved in changing some situation in human affairs. In contrast to other kinds of divine action, the expression "divine ''intervention''" implies that ...

and the "supernatural" that which science could now explain. This criticism brought him up against the Sorbonne which, dominated by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, never stopped trying to censor him. In 1751, he was ordered to redact some propositions contrary to the teaching of the Church; having proposed 74,000 years for the age of the Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years. This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion (astrophysics), accretion, or Internal structure of Earth, core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating ...

, this was contrary to the Bible which, using the scientific method on data found in biblical concordances, dated it to around 6,000 years. The Church was also hostile to his no less illustrious contemporary Carl von Linné

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organi ...

, and some have concluded that the Church simply refused to believe that order existed in nature.

Individual liberty and the social contract

This effort to research and elucidate universal laws, and to determine their component parts, also became an important element in the construction of a philosophy ofindividualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

, where everyone had rights based only on fundamental human rights

Human rights are universally recognized moral principles or norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both national and international laws. These rights are considered inherent and inalienable, meaning th ...

. There developed the philosophical notion of the thoughtful subject

Subject ( "lying beneath") may refer to:

Philosophy

*''Hypokeimenon'', or ''subiectum'', in metaphysics, the "internal", non-objective being of a thing

**Subject (philosophy), a being that has subjective experiences, subjective consciousness, or ...

, an individual who could make decisions based on pure reason and no longer in the yoke of custom. In ''Two Treatises of Government

''Two Treatises of Government'' (full title: ''Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True O ...

'', John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

argued that property rights

The right to property, or the right to own property (cf. ownership), is often classified as a human right for natural persons regarding their Possession (law), possessions. A general recognition of a right to private property is found more rarely ...

are not held in common but are totally personal, and made legitimate by the work required to obtain the property, as well as its protection (recognition) by others. Once the idea of natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

is accepted, it becomes possible to form the modern view of what we would now call political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

.

In his famous essay '' Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?'' (, ), Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

defined the Lumières thus:

The Lumières' philosophy was thus based on the realities of a systematic, ordered and understandable world, which required Man also to think in an ordered and systematic way. As well as physical laws, this included ideas on the laws governing human affairs and the divine right of kings, leading to the idea that the monarch acts with the consent of the people, and not the other way around. This legal concept informed Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

's theory of the social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

as a reciprocal relationship between men, and more so between families and other groups, which would become increasingly stronger, accompanied by a concept of individual inalienable rights. The powers of God were moot amongst atheist Lumières.

The Lumières movement redefined the ideas of liberty, property and rationalism, which took on meanings that we still understand today, and introduced into political philosophy the idea of the free individual, liberty for all guaranteed by the State (and not the whim of the government) backed by a strong rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

.

To understand the interaction between the Age of Reason and the Lumières, one approach is to compare Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

with John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

. Hobbes, who lived for three quarters of the 17th century, had worked to create an ontology of human emotions, ultimately trying to make order out of an inherently chaotic universe. In the alternate, Locke saw in Nature a source of unity and universal rights, with the State's assurance of protection. This "culture revolution" over the 17th and 18th centuries was a battle between these two viewpoints of the relationship between Man and Nature.

This resulted, in France, in the spread of the notion of human rights, finding expression in the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (), set by France's National Constituent Assembly in 1789, is a human and civil rights document from the French Revolution; the French title can be translated in the modern era as "Decl ...

, which greatly influenced similar declarations of rights in the following centuries, and left in its wake global political upheaval. Especially in France and the United States, freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

, freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

and freedom of thought

Freedom of thought is the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.

Overview

Every person attempts to have a cognitive proficiency by developing knowledge, concepts, theo ...

were held to be fundamental rights.

Social values and manifests

Representation of the people

The core values supported by the Lumières werereligious tolerance

Religious tolerance or religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, ...

, liberty and social equality

Social equality is a state of affairs in which all individuals within society have equal rights, liberties, and status, possibly including civil rights, freedom of expression, autonomy, and equal access to certain public goods and social servi ...

.

In England, America and France, the application of these values resulted in a new definition of natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

and a separation of political power

In political science, power is the ability to influence or direct the actions, beliefs, or conduct of actors. Power does not exclusively refer to the threat or use of force (coercion) by one actor against another, but may also be exerted thro ...

. To these values may be added a love of nature and the cult of reason.

Philosophical goals

The ideal figure of the Lumières was a philosopher, a

The ideal figure of the Lumières was a philosopher, a man of letters

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the world of culture, either ...

with a social function of exercising his reason in all domains to guide his and others' conscience, to advocate a value system

In ethics and social sciences, value denotes the degree of importance of some thing or action, with the aim of determining which actions are best to do or what way is best to live ( normative ethics), or to describe the significance of different a ...

and use it in discussing the problems of the time. He is a committed individual, involved in society

A society () is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. ...

, an (''Encyclopédie

, better known as ''Encyclopédie'' (), was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes. It was edited by Denis ...

''; "Honest man who approaches everything with reason"), (Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during t ...

, "Who concerns himself with revealing error").

The rationalism of the Lumières was not to the exclusion of aesthetics. Reason and sentiment

Sentiment may refer to:

*Feelings, and emotions

*Public opinion, also called sentiment

*Sentimentality, an appeal to shallow, uncomplicated emotions at the expense of reason

*Sentimental novel, an 18th-century literary genre

* Market sentiment, op ...

went hand-in-hand in their philosophy. The thoughts of the Lumières were equally capable of intellectual rigour and sentimentality.

Despite controversy about the limits of their philosophy, especially when they denounced black slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, many Lumières criticised slavery, or colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

, or both, including Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

in ''De l'Esprit des Lois

''The Spirit of Law'' (French: ''De l'esprit des lois'', originally spelled ''De l'esprit des loix''), also known in English as ''The Spirit of heLaws'', is a treatise on political theory, as well as a pioneering work in comparative law by Mont ...

'' (while keeping a "personal" slave), Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

in '' Supplément au voyage de Bougainville'', Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

in ''Candide

( , ) is a French satire written by Voltaire, a philosopher of the Age of Enlightenment, first published in 1759. The novella has been widely translated, with English versions titled ''Candide: or, All for the Best'' (1759); ''Candide: or, The ...

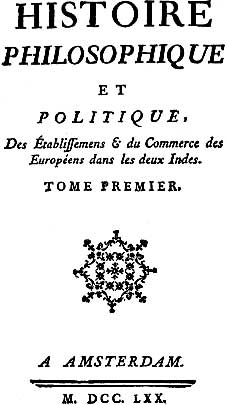

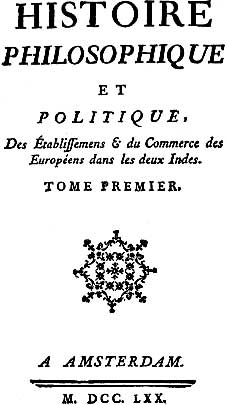

'' and Guillaume-Thomas Raynal in his encyclopaedic ''Histoire des deux Indes

The , more often known simply as , is an encyclopaedia on commerce between Europe and the Far East, Africa, and the Americas. It was published anonymously in Amsterdam in 1770 and attributed to Abbot Guillaume Thomas François Raynal, Guillaume ...

'', the very model of 18th-century anticolonialism

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholars of decolon ...

to which, among others, Diderot and d’Holbach contributed. It was stated without any proof that one of their number, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

, had shares in the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

.

Encyclopaedic goals

At the time, there was a particular taste for compendia of "all knowledge". This ideal found an instance in Diderot and d'Alembert's ("Encyclopaedia, or Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts"), usually known simply as the ''Encyclopédie

, better known as ''Encyclopédie'' (), was a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772, with later supplements, revised editions, and translations. It had many writers, known as the Encyclopédistes. It was edited by Denis ...

''. Published between 1750 and 1770 it aimed to lead people out of ignorance through the widest dissemination of knowledge.

Criticism

The Lumières movement was, for all its existence, pulled in two directions by opposing social forces: on one side, a strongspiritualism

Spiritualism may refer to:

* Spiritual church movement, a group of Spiritualist churches and denominations historically based in the African-American community

* Spiritualism (beliefs), a metaphysical belief that the world is made up of at leas ...

accompanied by a traditional faith in the religion of the Church; on the other, the rise of an anticlerical

Anti-clericalism is opposition to religious authority, typically in social or political matters. Historically, anti-clericalism in Christian traditions has been opposed to the influence of Catholicism. Anti-clericalism is related to secularism, ...

movement, critical of the differences between religious theory and practice, which was most manifest in France.

Anticlericism was not the only source of tension in France: some noblemen contested monarchical power and the upper classes wanted to see greater fruit from their labours. A relaxing of morals fomented opinion against absolutism and the Ancient Order. According to Dale K. Van Kley, Jansenism

Jansenism was a 17th- and 18th-century Christian theology, theological movement within Roman Catholicism, primarily active in Kingdom of France, France, which arose as an attempt to reconcile the theological concepts of Free will in theology, f ...

in France also became a source of division.

The French judicial system showed itself to be outdated. Even though commercial law had become codified during the 17th century, there was no uniform, or codified, civil law.

Voltaire

This social and legal background was criticised in works by the likes ofVoltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

. Exiled in England between 1726 and 1729, he studied the works of John Locke and Isaac Newton, and the English monarchy. He became well known for his denunciation of injustices such as those against Jean Calas

Jean Calas (1698 – 10 March 1762) was a merchant living in Toulouse, France, who was tried, judicially tortured, and executed for the murder of his son, despite his protestations of innocence. Calas was a Protestant in an officially Catholic so ...

, Pierre-Paul Sirven Pierre-Paul Sirven (1709–1777) is one of Voltaire's ''causes célèbres'' in his campaign to ''écraser l'infâme'' (crush infamy). Background

Sirven became an archivist and notary in Castres, southern France, in 1736. He was a Protestant with ...

, François-Jean de la Barre

François-Jean Lefebvre de la Barre (12 September 17451 July 1766) was a French nobleman. He was tortured and Decapitation, beheaded before his body was burnt on a pyre along with Voltaire's ''Dictionnaire philosophique, Philosophical Dictionar ...

and Thomas Arthur, comte de Lally

Thomas Arthur, comte de Lally, baron de Tollendal (13 January 17029 May 1766) was a French army officer. Lally commanded French forces, including two battalions of his own red-coated Regiment of Lally of the Irish Brigade, in India during the ...

.

The Lumières philosophy saw its climax in the middle of the 18th century.

For Voltaire, it was obvious that if the monarch can get the people to believe unreasonable things, then he can get them to ''do'' unreasonable things. This axiom became the basis for his criticism of the Lumières, and led to the basis of romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

: that constructions from pure reason created as many problems as they solved.

According to the Lumières philosophers, the crucial point of intellectual progress consisted of the synthesis of knowledge, enlightened by human reason, with the creation of a sovereign moral authority. A contrary point of view that developed, arguing that such a process would be swayed by social conventions, leading to a "New Truth" based on reason that was but a poor imitation of the ideal and unassailable truth.

The Lumières movement thus tried to find a balance between the idea of a "natural" liberty (or autonomy) and the freedom ''from'' that liberty, that is to say, the recognition that the autonomy found in nature was at odds with the discipline required for pure reason. At the same time, with various monarchs' reforms, there was a piecemeal attempt to redefine the order of society, and the relationship between monarch and subjects. The idea of a natural order was equally prevalent in scientific thought, for example, in the works of the biologist Carl von Linné

Carl Linnaeus (23 May 1707 – 10 January 1778), also known after ennoblement in 1761 as Carl von Linné, Blunt (2004), p. 171. was a Swedish biologist and physician who formalised binomial nomenclature, the modern system of naming organi ...

.

Kant

In Germany,Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

(like Rousseau, defining himself among the Lumières) heavily criticised the limitations of pure reason in his work ''Critique of Pure Reason

The ''Critique of Pure Reason'' (; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was foll ...

'' (), but also that of English empiricism in ''Critique of Practical Reason

The ''Critique of Practical Reason'' () is the second of Immanuel Kant's three critiques, published in 1788. Hence, it is sometimes referred to as the "second critique". It follows on from Kant's first critique, the ''Critique of Pure Reason'', ...

'' (). Compared with the rather subjective metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

of Descartes, Kant developed a more objective viewpoint in this branch of philosophy.

Adam Smith

Great thinkers at the end of the Lumières movement (Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, Thomas Jefferson and even the young Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

) adopted into their philosophy the ideas of self-organising and evolutionary forces. The Lumières' stance was then presented with reference to what was seen as a universal truth: that Good is fundamental in nature, but it is not self-evident. On the contrary, it is the advance of human reason that reveals this constant structure. Romanticism

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century. The purpose of the movement was to advocate for the importance of subjec ...

is the exact opposite of this stance.

Aestheticism

This resulted in reflections abouturbanism

Urbanism is the study of how inhabitants of urban areas, such as towns and cities, interact with the built environment. It is a direct component of disciplines such as urban planning, a profession focusing on the design and management of urban ...

. The Lumières' model town would be a joint effort between public provision and sympathetic architects, to create administrative or utilitarian buildings (town halls, hospitals, theatres, commissariats) all provided with views, squares, fountains, promenades, and so on.

The French Académie royale d'architecture

The Académie Royale d'Architecture (; ) was a French learned society founded in 1671. It had a leading role in influencing architectural theory and education, not only in France, but throughout Europe and the Americas from the late 17th centur ...

was of the opinion that ("The beautiful is the pleasant"). For Abbé Laugier

Marc-Antoine Laugier (Manosque, Provence, January 22, 1713 – Paris, April 5, 1769) was a Jesuit priest until 1755, then a Benedictine monk. Overlooking Claude Perrault and numerous other figures, Summerson notes,

Laugier is best known for ...

, on the contrary, the beautiful was that which was in line with rationality. The natural model for all architecture was the log cabin supported by four tree trunks, with four horizontal parts and a roof, respectively columns

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression member ...

, entablature

An entablature (; nativization of Italian , from "in" and "table") is the superstructure of moldings and bands which lies horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Entablatures are major elements of classical architecture, and ...

, and pediment

Pediments are a form of gable in classical architecture, usually of a triangular shape. Pediments are placed above the horizontal structure of the cornice (an elaborated lintel), or entablature if supported by columns.Summerson, 130 In an ...

s. The model of a Greek temple

Greek temples (, semantically distinct from Latin , " temple") were structures built to house deity statues within Greek sanctuaries in ancient Greek religion. The temple interiors did not serve as meeting places, since the sacrifices and ritu ...

was thus extended into the décor and the structure. This paradigm resulted in a change of style in the middle of the 18th century: Rococo

Rococo, less commonly Roccoco ( , ; or ), also known as Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and dramatic style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpte ...

was dismissed, Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

and Palladian architecture

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

became the principal references for neoclassical architecture

Neoclassical architecture, sometimes referred to as Classical Revival architecture, is an architectural style produced by the Neoclassicism, Neoclassical movement that began in the mid-18th century in Italy, France and Germany. It became one of t ...

.

The

The University of Virginia

The University of Virginia (UVA) is a Public university#United States, public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson and contains his The Lawn, Academical Village, a World H ...

, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

, was founded by Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

. He drew up plans for parts of the campus based on the values of the Lumières.

The Place Stanislas

The Place Stanislas is a large Pedestrian zone, pedestrianised Town Square, square in the France, French city of Nancy, France, Nancy, in the Lorraine historic region. Built between 1752 and 1756 on the orders of Stanislaus I, former King of Polan ...

at Nancy, France

Nancy is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the northeastern Departments of France, French department of Meurthe-et-Moselle. It was the capital of the Duchy of Lorraine, which was Lorraine and Barrois, annexed by France under King Louis X ...

is the focus of an array of neoclassical urban buildings, and has been on the UNESCO List of World Heritage Sites in France

This is a list of World Heritage Sites in France with properties of Cultural heritage, cultural and natural heritage in France as inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage Site, World Heritage List or as on the country's tentative list.Place de la Carrière

Place may refer to:

Geography

* Place (United States Census Bureau), defined as any concentration of population

** Census-designated place, a populated area lacking its own municipal government

* "Place", a type of street or road name

** Ofte ...

and the Place d’Alliance

Place may refer to:

Geography

* Place (United States Census Bureau), defined as any concentration of population

** Census-designated place, a populated area lacking its own municipal government

* "Place", a type of street or road name

** Of ...

, the administrative centre of the time.

Claude Nicolas Ledoux

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (; 21 March 1736 – 18 November 1806) was one of the earliest exponents of French Neoclassical architecture. He used his knowledge of architectural theory to design not only domestic architecture but also town planning; ...

(1736 – 1806) was a member of the Académie d'Architecture was without doubt the architect whose projects best represented the utopian, purely rational environment. (That which is rational, and thus based in the understanding of nature, cannot be at the same time utopian.) Starting in 1775 he built the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, a very industrial city in Doubs

Doubs (, ; ; ) is a department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in Eastern France. Named after the river Doubs, it had a population of 543,974 in 2019.French Revolution of 1789.

The philosophers of the Lumières movementIn French, the term (as a collective noun) is used to designate the free-thinkers, writers and philosophers who embraced a particular philosophy; it might be regarded as an abuse of language to use it to refer to the philosophy itself. came with many different talents:

The philosophers of the Lumières movementIn French, the term (as a collective noun) is used to designate the free-thinkers, writers and philosophers who embraced a particular philosophy; it might be regarded as an abuse of language to use it to refer to the philosophy itself. came with many different talents:

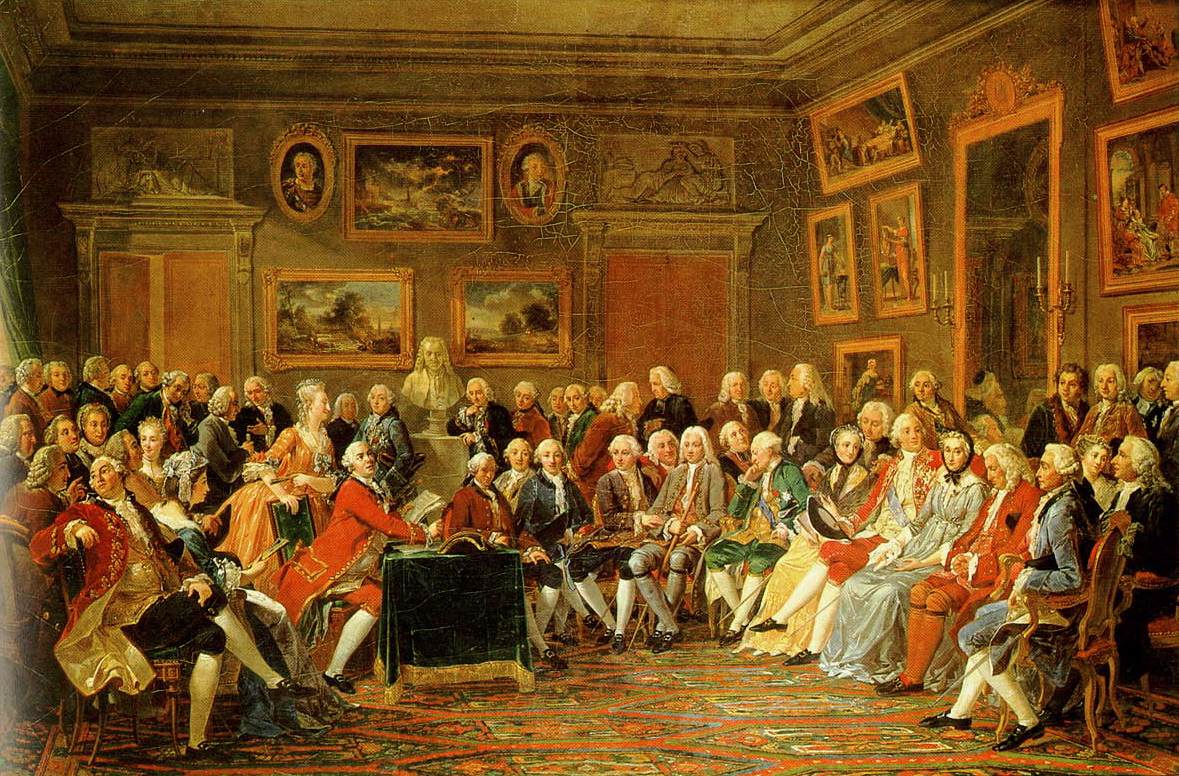

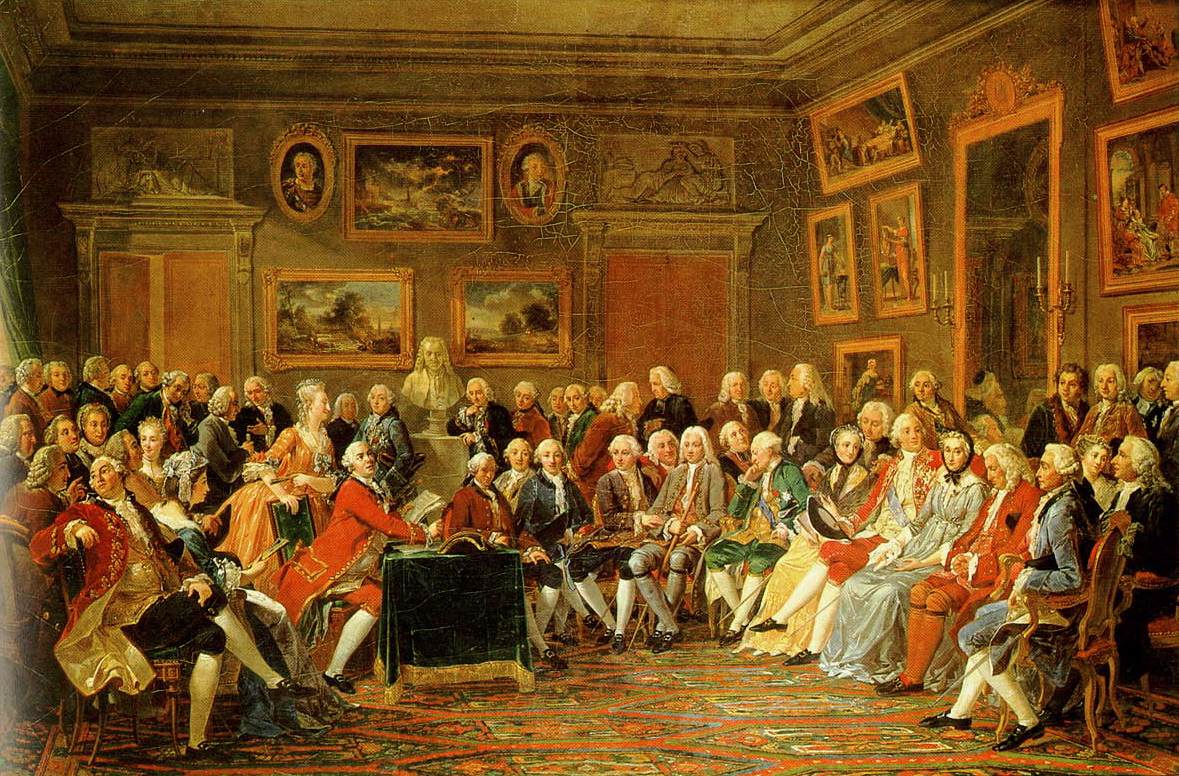

At first, literary cafés such as the Café Procope in Paris, were the favoured night-time haunt of young poets and critics, who could read and debate, and bragg about their latest success in the theatre or bookshops. But these were eclipsed by (Literary cafés), open to all who had some talent, at least for public speaking. Their defining characteristic was their intellectual mix; men would gather to express their views and satisfy their thirst for knowledge and to establish their world-view. But it was necessary to be "introduced" into these salons: received artists, thinkers and philosophers. Each hostess had her day, her speciality and her special guests. The model example is the hotel of Madame de Lambert (Anne-Thérèse de Marguenat de Courcelles) at the turn of the century.

Talented men regularly decamped there to expound their ideas and test their latest work on a privileged public. Worldly and cultured, the ''grandes dames'' who set up these salons enlivened the ''soirées'', encouraging the timid and cutting short arguments. Having strong, relatively liberated personalities, they were often writers and diarists themselves.

This social mixing was particularly prominent in 18th-century France, in the "" ("General States of Human Spirit") where the Lumières philosophy flourished. Some cultured women were treated as equal to the men on questions of religion, politics and science, and could bring a certain stylishness to debate, for example the contributions of Anne Dacier to the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, and the works of

At first, literary cafés such as the Café Procope in Paris, were the favoured night-time haunt of young poets and critics, who could read and debate, and bragg about their latest success in the theatre or bookshops. But these were eclipsed by (Literary cafés), open to all who had some talent, at least for public speaking. Their defining characteristic was their intellectual mix; men would gather to express their views and satisfy their thirst for knowledge and to establish their world-view. But it was necessary to be "introduced" into these salons: received artists, thinkers and philosophers. Each hostess had her day, her speciality and her special guests. The model example is the hotel of Madame de Lambert (Anne-Thérèse de Marguenat de Courcelles) at the turn of the century.

Talented men regularly decamped there to expound their ideas and test their latest work on a privileged public. Worldly and cultured, the ''grandes dames'' who set up these salons enlivened the ''soirées'', encouraging the timid and cutting short arguments. Having strong, relatively liberated personalities, they were often writers and diarists themselves.

This social mixing was particularly prominent in 18th-century France, in the "" ("General States of Human Spirit") where the Lumières philosophy flourished. Some cultured women were treated as equal to the men on questions of religion, politics and science, and could bring a certain stylishness to debate, for example the contributions of Anne Dacier to the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, and the works of

Key figures

Philosophers

Origins

The philosophers of the Lumières movementIn French, the term (as a collective noun) is used to designate the free-thinkers, writers and philosophers who embraced a particular philosophy; it might be regarded as an abuse of language to use it to refer to the philosophy itself. came with many different talents:

The philosophers of the Lumières movementIn French, the term (as a collective noun) is used to designate the free-thinkers, writers and philosophers who embraced a particular philosophy; it might be regarded as an abuse of language to use it to refer to the philosophy itself. came with many different talents: Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

had had a legal education but was equally at home with archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

and architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

; Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

had been a career diplomat and was a physicist. Condorcet wrote on subjects as wide-ranging as commerce, finance, education and science.

The social origins of the philosophers were also diverse: many were from middle-class families (Voltaire, Jefferson), others from more modest beginnings (Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

, Franklin, Diderot) or from the nobility (Montesquieu, Condorcet). Some had had a religious education (Diderot, Louis de Jaucourt) or one in the law (Montesquieu, Jefferson).

The philosophers formed networks and communicated in letters; the vitriolic correspondence between Rousseau and Voltaire is well known. The great figures of the 18th century met and debated in the salons, cafés or academies

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

. These thinkers and formed an international community. Franklin, Jefferson, Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

, David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; – 25 August 1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist who was best known for his highly influential system of empiricism, philosophical scepticism and metaphysical naturalism. Beg ...

and Ferdinando Galiani

Ferdinando Galiani (2 December 1728, Chieti, Kingdom of Naples – 30 October 1787, Naples, Kingdom of Naples), known in French contexts as ''Abbé'' Galiani, was an Italian economist, a leading Italian figure of the Enlightenment. Friedrich Niet ...

all spent many years in France.

Because they criticised the established order, the philosophers were chased by the authorities and had to resort to subterfuge to escape prison. François-Marie Arouet took on the pseudonym Voltaire. In 1774, Thomas Jefferson wrote a report on behalf of the Virginia delegates to the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates of twelve of the Thirteen Colonies held from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia at the beginning of the American Revolution. The meeting was organized b ...

, which was convened to discuss the grievances of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

's American colonies. Because its content, he could only publish it anonymously. Diderot's (" Letter on the Blind for the Use of those who can See") landed him in prison at the Château de Vincennes

The Château de Vincennes () is a former fortress and royal residence next to the town of Vincennes, on the eastern edge of Paris, alongside the Bois de Vincennes. It was largely built between 1361 and 1369, and was a preferred residence, after ...

. Voltaire was accused of writing pamphlets criticising Philippe II, Duke of Orléans

Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (Philippe Charles; 2 August 1674 – 2 December 1723), who was known as the Regent, was a French prince, soldier, and statesman who served as Regent of the Kingdom of France from 1715 to 1723. He is referred to i ...

(1674–1723), and imprisoned in the Bastille

The Bastille (, ) was a fortress in Paris, known as the Bastille Saint-Antoine. It played an important role in the internal conflicts of France and for most of its history was used as a state prison by the kings of France. It was stormed by a ...

. in 1721, Montesquieu published ("Persian Letters

''Persian Letters'' () is a literary work, published in 1721, by Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu, recounting the experiences of two fictional Persian noblemen, Usbek and Rica, who spend several years in France under Louis XIV and the ...

") anonymously in Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former provinces of the Netherlands, province on the western coast of the Netherland ...

. From 1728 to 1734, he went to many European countries.

Faced with censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governmen ...

and in financial difficulty, the philosophers often resorted to the protection of aristocrats and patrons: Chrétien Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes Chrétien is a given name and surname. In the French language, ''Chrétien'' is the masculine form of "Christian", as noun, adjective or adverb. Notable people with the name include:

Given name

* Chrétien de Troyes, 12th-century French poet

* ...

and Madame de Pompadour

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour (, ; 29 December 1721 – 15 April 1764), commonly known as Madame de Pompadour, was a member of the French court. She was the official chief mistress of King Louis XV from 1745 to 1751, and rema ...

, chief mistress of Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reached maturity (then defi ...

, supported Diderot. Marie-Thérèse Rodet Geoffrin (1699 – 1777) paid part of the publishing costs of the ''Encyclopédie''. From 1749 to 1777 she held a fortnightly , inviting artists, intellectuals, men of letters and philosophers. The other great ''salon'' of the time was that of Claudine Guérin de Tencin

Claudine Alexandrine Guérin de Tencin, Baroness of Saint-Martin-de-Ré (27 April 1682 – 4 December 1749) was a French Salon (gathering), salonist and author. She was the mother of Jean le Rond d'Alembert, who later became a prominent mathemat ...

. In the 1720s, Voltaire exiled himself in England, where he absorbed Locke's ideas.

The philosophers were, in general, less hostile to monarchical rule than they were to that of the clergy and the nobility. In his defence of Jean Calas

Jean Calas (1698 – 10 March 1762) was a merchant living in Toulouse, France, who was tried, judicially tortured, and executed for the murder of his son, despite his protestations of innocence. Calas was a Protestant in an officially Catholic so ...

, Voltaire defended Royal justice against the excesses of fantastical provincial courts. Many European monarchs – Charles III of Spain

Charles III (; 20 January 1716 – 14 December 1788) was King of Spain in the years 1759 to 1788. He was also Duke of Parma and Piacenza, as Charles I (1731–1735); King of Naples, as Charles VII; and King of Sicily, as Charles III (or V) (1735� ...

, Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa (Maria Theresia Walburga Amalia Christina; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was the ruler of the Habsburg monarchy from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position suo jure, in her own right. She was the ...

of the House of Habsburg, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II (13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from 18 August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy from 29 November 1780 until his death. He was the eldest son of Empress Maria Theresa and her husband, Francis I, ...

, Catherine II of Russia

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

, Gustave III of Sweden

Gustav III (29 March 1792), also called ''Gustavus III'', was King of Sweden from 1771 until his assassination in 1792. He was the eldest son of King Adolf Frederick and Queen Louisa Ulrika of Sweden.

Gustav was a vocal opponent of what he saw ...

– met with philosophers such as Voltaire, who was presented to the Court of Frederick the Great

Frederick II (; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was the monarch of Prussia from 1740 until his death in 1786. He was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled ''King in Prussia'', declaring himself ''King of Prussia'' after annexing Royal Prussia ...

, and Diderot, who was presented to the Court of Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

. Philosophers such as d'Holbach were advocates of "enlightened absolutism

Enlightened absolutism, also called enlightened despotism, refers to the conduct and policies of European absolute monarchs during the 18th and early 19th centuries who were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, espousing them to enhanc ...

" in the hope that their ideas would spread more quickly if they had the approval of the Head of State. Subsequent events would show the philosophers the limits of such an approach with sovereigns who were , "more absolutist than enlightened". Only Rousseau stuck rigidly to the revolutionary ideal of political equality.

Notable members

=France

= *Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle (; 18 November 1647 – 28 December 1706) was a French philosopher, author, and lexicographer. He is best known for his '' Historical and Critical Dictionary'', whose publication began in 1697. Many of the more controversial ideas ...

, Émilie du Châtelet

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet (; 17 December 1706 – 10 September 1749) was a French mathematician and physicist.

Her most recognized achievement is her philosophical magnum opus, ''Institutions de Physique'' ...

, Étienne Bonnot de Condillac

Étienne Bonnot de Condillac ( ; ; 30 September 1714 – 2 August or 3 August 1780) was a French philosopher, epistemologist, and Catholic priest, who studied in such areas as psychology and the philosophy of the mind.

Biography

He was born a ...

, Nicolas de Condorcet

Nicolas or Nicolás may refer to:

People Given name

* Nicolas (given name)

Mononym

* Nicolas (footballer, born 1999), Brazilian footballer

* Nicolas (footballer, born 2000), Brazilian footballer

Surname Nicolas

* Dafydd Nicolas (c.1705–1774), ...

, Denis Diderot

Denis Diderot (; ; 5 October 171331 July 1784) was a French philosopher, art critic, and writer, best known for serving as co-founder, chief editor, and contributor to the along with Jean le Rond d'Alembert. He was a prominent figure during th ...

, Jean le Rond D'Alembert

Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert ( ; ; 16 November 1717 – 29 October 1783) was a French mathematician, mechanician, physicist, philosopher, and music theorist. Until 1759 he was, together with Denis Diderot, a co-editor of the ''Encyclopé ...

, Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges (; born Marie Gouze; 7 May 17483 November 1793) was a French playwright and political activist. She is best known for her Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen and other writings on women's rights and Abol ...

, Vincent de Gournay, D'Holbach

Paul Thiry, Baron d'Holbach (; ; 8 December 1723 – 21 January 1789), known as d'Holbach, was a Franco-German philosopher, encyclopedist and writer, who was a prominent figure in the French Enlightenment. He was born in Edesheim, near Landau ...

, Bernard Le Bouyer de Fontenelle

Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle (; ; 11 February 1657

– 9 January 1757), also called Bernard Le Bouyer de Fontenelle, was a French author and an influential member of three of the academies of the Institut de France, noted especially for his ...

, Claude-Adrien Helvétius, Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier de La Fayette, Marquis de La Fayette (; 6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (), was a French military officer and politician who volunteered to join the Conti ...

, Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier, La Mettrie

Julien Offray de La Mettrie (; November 23, 1709 – November 11, 1751) was a French physician and philosopher, and one of the earliest of the French materialists of the Enlightenment. He is best known for his 1747 work '' L'homme machine'' ('' ...

, Louis de Jaucourt, Jean-François Marmontel

Jean-François Marmontel (; 11 July 1723 – 31 December 1799) was a French historian, writer and a member of the Encyclopédistes movement.

Biography

He was born of poor parents at Bort, Limousin (today in Corrèze). After studying wi ...

, Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis

Pierre Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (; ; 1698 – 27 July 1759) was a French mathematician, philosopher and man of letters. He became the director of the Académie des Sciences and the first president of the Prussian Academy of Science, at the i ...

, Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

, François Quesnay

François Quesnay (; ; 4 June 1694 – 16 December 1774) was a French economist and physician of the Physiocratic school. He is known for publishing the " Tableau économique" (Economic Table) in 1758, which provided the foundations of the ideas ...

, Antoine Destutt de Tracy

Antoine Louis Claude Destutt, comte de Tracy (; 20 July 1754 – 9 March 1836) was a French Enlightenment aristocrat and philosopher who coined the term "ideology".

Biography

The son of a distinguished soldier, Claude Destutt, he was born in ...

, Anne Robert Jacques Turgot

Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, Baron de l'Aulne ( ; ; 10 May 172718 March 1781), commonly known as Turgot, was a French economist and statesman. Sometimes considered a physiocrat, he is today best remembered as an early advocate for economic lib ...

, Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

, Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (; 7 September 1707 – 16 April 1788) was a French Natural history, naturalist, mathematician, and cosmology, cosmologist. He held the position of ''intendant'' (director) at the ''Jardin du Roi'', now ca ...

=World

= * England: Anthony Collins,John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

, Edward Gibbon

Edward Gibbon (; 8 May 173716 January 1794) was an English essayist, historian, and politician. His most important work, ''The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'', published in six volumes between 1776 and 1789, is known for ...

, William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous fo ...

, Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke

Henry St. John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke (; 16 September 1678 – 12 December 1751) was an English politician, government official and political philosopher. He was a leader of the Tory (British political party), Tories, and supported the ...

, Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

, James Oglethorpe

Lieutenant-General James Edward Oglethorpe (22 December 1696 – 30 June 1785) was a British Army officer, Tory politician and colonial administrator best known for founding the Province of Georgia in British North America. As a social refo ...

, William Paley

William Paley (July 174325 May 1805) was an English Anglican clergyman, Christian apologetics, Christian apologist, philosopher, and Utilitarianism, utilitarian. He is best known for his natural theology exposition of the teleological argument ...

, Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley (; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, Natural philosophy, natural philosopher, English Separatist, separatist theologian, Linguist, grammarian, multi-subject educator and Classical libera ...

, William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

, Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft ( , ; 27 April 175910 September 1797) was an English writer and philosopher best known for her advocacy of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional ...

*Ireland: George Berkeley

George Berkeley ( ; 12 March 168514 January 1753), known as Bishop Berkeley (Bishop of Cloyne of the Anglican Church of Ireland), was an Anglo-Irish philosopher, writer, and clergyman who is regarded as the founder of "immaterialism", a philos ...

, Richard Cantillon

Richard Cantillon (; 1680s – ) was an Irish-French economist and author of '' Essai Sur La Nature Du Commerce En Général'' (''Essay on the Nature of Trade in General''), a book considered by William Stanley Jevons to be the "cradle of ...

, John Toland

John Toland (30 November 167011 March 1722) was an Irish rationalist philosopher and freethinker, and occasional satirist, who wrote numerous books and pamphlets on political philosophy and philosophy of religion, which are early expressions ...

* Germany (Prussia): Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi

Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (; ; 25 January 1743 – 10 March 1819) was a German philosopher, writer and socialite. He is best known for popularizing the concept of nihilism. He promoted the idea that it is the necessary result of Enlightenment th ...

, Johann Gottfried von Herder

Johann Gottfried von Herder ( ; ; 25 August 174418 December 1803) was a Prussian philosopher, theologian, pastor, poet, and literary critic. Herder is associated with the Age of Enlightenment, ''Sturm und Drang'', and Weimar Classicism. He was ...

, Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (; ; 22 January 1729 – 15 February 1781) was a German philosopher, dramatist, publicist and art critic, and a representative of the Enlightenment era. His plays and theoretical writings substantially influenced the dev ...

, Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn (6 September 1729 – 4 January 1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian. His writings and ideas on Jews and the Jewish religion and identity were a central element in the development of the ''Haskalah'', or 'J ...

*Italy: Cesare Beccaria

Cesare Bonesana di Beccaria, Marquis of Gualdrasco and Villareggio (; 15 March 1738 – 28 November 1794) was an Italian criminologist, jurist, philosopher, economist, and politician who is widely considered one of the greatest thinkers of the ...

, Ferdinando Galiani

Ferdinando Galiani (2 December 1728, Chieti, Kingdom of Naples – 30 October 1787, Naples, Kingdom of Naples), known in French contexts as ''Abbé'' Galiani, was an Italian economist, a leading Italian figure of the Enlightenment. Friedrich Niet ...

, Mario Pagano

Francesco Mario Pagano (8 December 1748 – 29 October 1799) was an Italian jurist, author, thinker, and the founder of the Neapolitan school of law.''The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Political Thought'', ed. Goldie & Wokler, 2006, p. ...

, Giambattista Vico

Giambattista Vico (born Giovan Battista Vico ; ; 23 June 1668 – 23 January 1744) was an Italian philosopher, rhetorician, historian, and jurist during the Italian Enlightenment. He criticized the expansion and development of modern rationali ...

, Pietro Verri