Lucretia Coffin Mott on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lucretia Mott (''née''

Mott and Cady Stanton became well acquainted at the World's Anti-Slavery Convention. Cady Stanton later recalled that they first discussed the possibility of a women's rights convention in London.

Women's rights activists advocated a range of issues, including equality in marriage, such as women's property rights and rights to their earnings. At that time it was very difficult to obtain divorce, and fathers were almost always granted custody of children. Cady Stanton sought to make divorce easier to obtain and to safeguard women's access to and control of their children. Though some early feminists disagreed, and viewed Cady Stanton's proposal as scandalous, Mott stated "her great faith in Elizabeth Stanton's quick instinct & clear insight in all appertaining to women's rights."

Mott's theology was influenced by

Mott and Cady Stanton became well acquainted at the World's Anti-Slavery Convention. Cady Stanton later recalled that they first discussed the possibility of a women's rights convention in London.

Women's rights activists advocated a range of issues, including equality in marriage, such as women's property rights and rights to their earnings. At that time it was very difficult to obtain divorce, and fathers were almost always granted custody of children. Cady Stanton sought to make divorce easier to obtain and to safeguard women's access to and control of their children. Though some early feminists disagreed, and viewed Cady Stanton's proposal as scandalous, Mott stated "her great faith in Elizabeth Stanton's quick instinct & clear insight in all appertaining to women's rights."

Mott's theology was influenced by

After the Civil War, Mott was elected the first president of the American Equal Rights Association, an organization that advocated universal suffrage. She resigned from the association in 1868 when

After the Civil War, Mott was elected the first president of the American Equal Rights Association, an organization that advocated universal suffrage. She resigned from the association in 1868 when

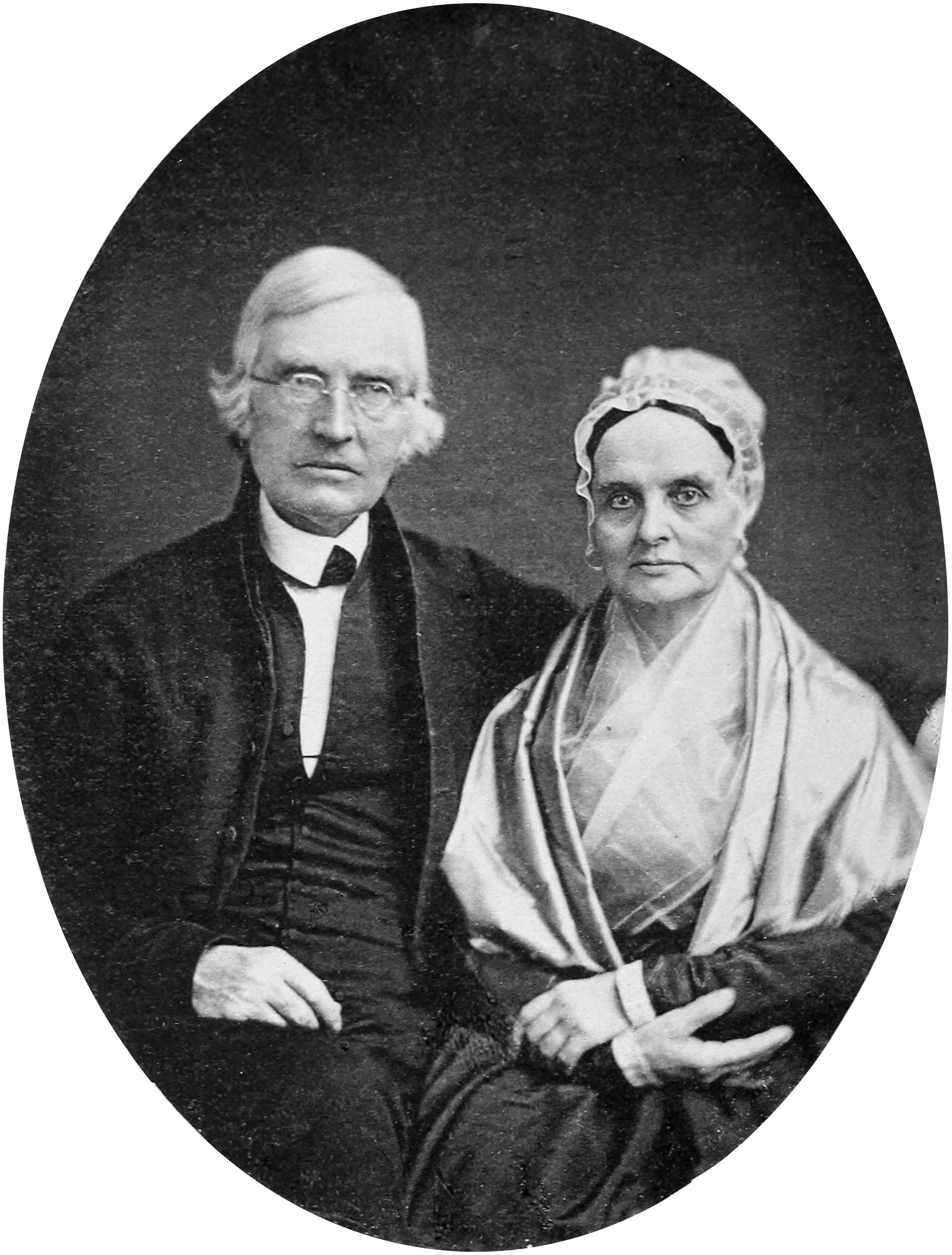

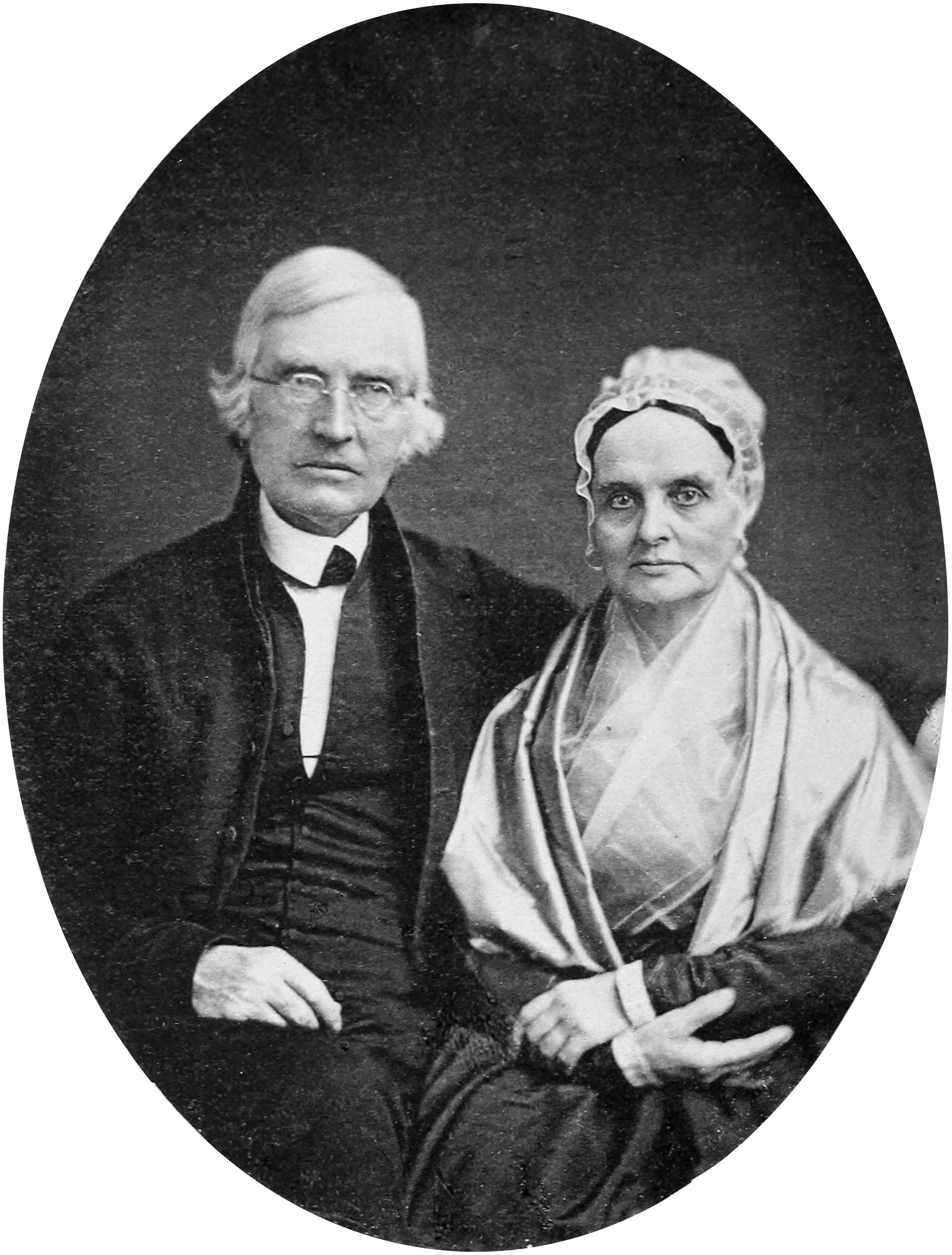

On April 10, 1811, Lucretia Coffin married James Mott at Pine Street Meeting in Philadelphia. They had six children. Their second child, Thomas Mott, died at age two. Their surviving children all became active in the anti-slavery and other reform movements, following in their parents' paths. Her great-granddaughter

On April 10, 1811, Lucretia Coffin married James Mott at Pine Street Meeting in Philadelphia. They had six children. Their second child, Thomas Mott, died at age two. Their surviving children all became active in the anti-slavery and other reform movements, following in their parents' paths. Her great-granddaughter

Lucretia Coffin Mott

''Discourse on woman'', 1849 (From a book, Chapter 6, without pagination, continuous text), in google books

Lucretia Mott

Women's Rights, National Historical Park, New York, National Park Service

* Th

Mott Manuscripts

held a

Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mott, Lucretia 1793 births 1880 deaths 19th-century American women writers 19th-century Quakers American abolitionists American anti-war activists American Christian pacifists American Quakers American social reformers American suffragists Quaker abolitionists Deaths from pneumonia in Pennsylvania Political activists from Pennsylvania People from Cheltenham, Pennsylvania People from Nantucket, Massachusetts Quaker ministers University and college founders Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania Quaker feminists Women civil rights activists

Coffin

A coffin is a funerary box used for viewing or keeping a corpse, either for burial or cremation.

Sometimes referred to as a casket, any box in which the dead are buried is a coffin, and while a casket was originally regarded as a box for jewel ...

; January 3, 1793 – November 11, 1880) was an American Quaker

Quakers (or Friends) are members of a Christian religious movement that started in England as a form of Protestantism in the 17th century, and has spread throughout North America, Central America, Africa, and Australia. Some Quakers originally c ...

, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongst the women excluded from the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London in 1840. In 1848 she was invited by Jane Hunt to a meeting that led to the first public gathering about women's rights, the Seneca Falls Convention, during which Mott co-wrote the Declaration of Sentiments.

Her speaking abilities made her an important abolitionist, feminist, and reformer; she had been a Quaker preacher early in her adulthood. When the United States outlawed slavery in 1865, she advocated giving former slaves, both male and female, the right to vote (suffrage). She remained a central figure in reform movements until her death in 1880. The area around her long-time residence in Cheltenham Township

Cheltenham Township is a home rule township in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, United States. Cheltenham's population density ranges from over 10,000 per square mile (25,900 per square kilometer) in rowhouses and high-rise apartments along Chelte ...

is now known as La Mott, in her honor.

Early life and education

Lucretia Coffin was born January 3, 1793, inNantucket

Nantucket () is an island about south from Cape Cod. Together with the small islands of Tuckernuck and Muskeget, it constitutes the Town and County of Nantucket, a combined county/town government that is part of the U.S. state of Massachuse ...

, Massachusetts, the second child of Anna Folger and Thomas Coffin. Through her mother, she was a descendant of Peter Folger and Mary Morrell Folger, early settlers of the colony. Her cousin was Benjamin Franklin, one of the Framers of the Constitution, while other Folger relatives were Tories, those who remained loyal to the British Crown

The Crown is the state (polity), state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, British Overseas Territories, overseas territories, Provinces and territorie ...

during the American Revolution.

She was sent at the age of 13 to the Nine Partners School, located in Dutchess County, New York, which was run by the Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

(Quakers). There she became a teacher after graduation. Her interest in women's rights began when she discovered that male teachers at the school were paid significantly more than female staff. After her family moved to Philadelphia, she and James Mott, another teacher at Nine Partners, followed.

Abolitionist

Early anti-slavery efforts

Like most Quakers, Mott considered slavery to be evil. Inspired in part by minister Elias Hicks, she and other Quakers refused to use cotton cloth, cane sugar, and other slavery-produced goods. In 1821, Mott became a Quaker minister. With her husband's support, she traveled extensively as a minister, and her sermons emphasized the Quaker inward light or the presence of the Divine within every individual. Her sermons also included herfree produce

The free-produce movement was an international boycott of goods produced by slave labor. It was used by the abolitionist movement as a non-violent way for individuals, including the disenfranchised, to fight slavery.

In this context, ''free'' ...

and anti-slavery sentiments. In 1833, her husband helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS; 1833–1870) was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society ...

.

By then an experienced minister and abolitionist, Lucretia Mott was the only woman to speak at the organizational meeting in Philadelphia. She tested the language of the society's Constitution and bolstered support when many delegates were precarious. Days after the conclusion of the convention, at the urging of other delegates, Mott and other white and black women founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Integrated from its founding, the organization opposed both slavery and racism, and developed close ties to Philadelphia's Black community. Mott herself often preached at Black parishes. Around this time, Mott's sister-in-law, Abigail Lydia Mott, and brother-in-law, Lindley Murray Moore, were helping to found the Rochester Anti-Slavery Society

Rochester may refer to:

Places Australia

* Rochester, Victoria

Canada

* Rochester, Alberta

United Kingdom

*Rochester, Kent

** City of Rochester-upon-Medway (1982–1998), district council area

** History of Rochester, Kent

**HM Prison ...

(see Julia Griffiths

Julia Griffiths (21 May 1811 – 1895) was a British abolitionist who worked with the American former slave Frederick Douglass. The two met in London, England, during Douglass's tour of the British Isles in 1845–47. In 1849, Griffiths joined Do ...

).

Amidst social persecution by abolition opponents and pain from dyspepsia, Mott continued her work for the abolitionist cause. She managed their household budget to extend hospitality to guests, including fugitive slaves, and donated to charities. Mott was praised for her ability to maintain her household while contributing to the cause. In the words of one editor, "She is proof that it is possible for a woman to widen her sphere without deserting it."

Mott and other female activists also organized anti-slavery fairs to raise awareness and revenue, providing much of the funding for the movement.

Women's participation in the anti-slavery movement threatened societal norms. Many members of the abolitionist movement opposed public activities by women, especially public speaking. At the Congregational Church

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

General Assembly, delegates agreed on a pastoral letter warning women that lecturing directly defied St. Paul's instruction for women to keep quiet in church.( 1 Timothy 2:12) Other people opposed women's speaking to mixed crowds of men and women, which they called "promiscuous." Others were uncertain about what was proper, as the rising popularity of the Grimké sisters and other women speakers attracted support for abolition.

Mott attended all three national Anti-Slavery Conventions of American Women (1837, 1838, 1839). During the 1838 convention in Philadelphia, a mob destroyed Pennsylvania Hall, a newly opened meeting place built by abolitionists. Mott and the white and black women delegates linked arms to exit the building safely through the crowd. Afterward, the mob targeted her home and Black institutions and neighborhoods in Philadelphia. As a friend redirected the mob, Mott waited in her parlor, willing to face her violent opponents.

Mott was involved in a number of anti-slavery organizations, including the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society (founded in 1838), the American Free Produce Association, and the American Anti-Slavery Society.

World's Anti-Slavery Convention

In June 1840, Mott attended theGeneral Anti-Slavery Convention

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

, better known as the World's Anti-Slavery Convention, in London, England. In spite of Mott's status as one of six women delegates, before the conference began, the men voted to exclude the American women from participating, and the female delegates were required to sit in a segregated area. Anti-slavery leaders didn't want the women's rights issue to become associated with the cause of ending slavery worldwide and dilute the focus on abolition. In addition, the social mores of the time denied women's full participation in public political life. Several of the American men attending the convention, including William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips, protested the women's exclusion. Garrison, Nathaniel Peabody Rogers

Nathaniel Peabody Rogers (June 3, 1794 – October 16, 1846) was an American attorney turned abolitionist writer, who served, from June 1838 until June 1846, as editor of the New England anti-slavery newspaper '' Herald of Freedom''. He was also ...

, William Adam, and African American activist Charles Lenox Remond sat with the women in the segregated area.

Activists Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

and her husband Henry Brewster Stanton

Henry Brewster Stanton (June 27, 1805 – January 14, 1887) was an American abolitionist, social reformer, attorney, journalist and politician. His writing was published in the '' New York Tribune,'' the ''New York Sun,'' and William Lloy ...

attended the convention while on their honeymoon. Stanton admired Mott, and the two women became united as friends and allies.

One Irish reporter deemed her the "Lioness of the Convention". Mott was among the women included in the commemorative painting of the convention, which also featured female British activists: Elizabeth Pease

Elizabeth Nichol (''née'' Pease; 5 January 1807 – 3 February 1897) was a 19th-century British Abolitionism in the United Kingdom, abolitionist, anti-segregationist, women's suffrage, woman suffragist, chartism, chartist and anti-vivisectionis ...

, Mary Anne Rawson

Mary Anne Rawson (1801–1887) was a slavery abolitionist above all. She was also a campaigner with the Tract Society and the British and Foreign Bible Society, for Italian nationalism and against child labour. She was first involved with a S ...

, Anne Knight

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

, Elizabeth Tredgold and Mary Clarkson, daughter of Thomas Clarkson. Benjamin Haydon the painting's creator had intended to give Mott a prominent place in the painting. However during a sitting on 29 June 1840 to capture her likeness, he took a dislike to her views and decided to not use her portrait prominently.

Encouraged by active debates in England and Scotland, Mott also returned with new energy for the anti-slavery cause in the United States. She and her husband allowed their Philadelphia-area home, called Roadside, in the district now known as La Mott, to be used as a stop on the Underground Railroad. She continued an active public lecture schedule, with destinations including the major Northern cities of New York City and Boston, as well as travel over several weeks to slave-owning states, with speeches in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore was d ...

, Maryland and other cities in Virginia. She arranged to meet with slave owners to discuss the morality of slavery. In the District of Columbia, Mott timed her lecture to coincide with the return of Congress from Christmas recess; more than 40 Congressmen attended. She had a personal audience with President John Tyler who, impressed with her speech, said, "I would like to hand Mr. Calhoun over to you", referring to the senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

and abolition opponent.

Women's rights

Overview

Mott and Cady Stanton became well acquainted at the World's Anti-Slavery Convention. Cady Stanton later recalled that they first discussed the possibility of a women's rights convention in London.

Women's rights activists advocated a range of issues, including equality in marriage, such as women's property rights and rights to their earnings. At that time it was very difficult to obtain divorce, and fathers were almost always granted custody of children. Cady Stanton sought to make divorce easier to obtain and to safeguard women's access to and control of their children. Though some early feminists disagreed, and viewed Cady Stanton's proposal as scandalous, Mott stated "her great faith in Elizabeth Stanton's quick instinct & clear insight in all appertaining to women's rights."

Mott's theology was influenced by

Mott and Cady Stanton became well acquainted at the World's Anti-Slavery Convention. Cady Stanton later recalled that they first discussed the possibility of a women's rights convention in London.

Women's rights activists advocated a range of issues, including equality in marriage, such as women's property rights and rights to their earnings. At that time it was very difficult to obtain divorce, and fathers were almost always granted custody of children. Cady Stanton sought to make divorce easier to obtain and to safeguard women's access to and control of their children. Though some early feminists disagreed, and viewed Cady Stanton's proposal as scandalous, Mott stated "her great faith in Elizabeth Stanton's quick instinct & clear insight in all appertaining to women's rights."

Mott's theology was influenced by Unitarians

Unitarian or Unitarianism may refer to:

Christian and Christian-derived theologies

A Unitarian is a follower of, or a member of an organisation that follows, any of several theologies referred to as Unitarianism:

* Unitarianism (1565–present) ...

including Theodore Parker and William Ellery Channing as well as early Quakers including William Penn. She thought that "the kingdom of God is within man" (1749) and was part of the group of religious liberals who formed the Free Religious Association in 1867, with Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise

Isaac Mayer Wise (29 March 1819, Lomnička – 26 March 1900, Cincinnati) was an American Reform rabbi, editor, and author. At his death he was called "the foremost rabbi in America".

Early life

Wise was born on 29 March 1819 in Steingrub in B ...

, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

In 1866, Mott joined with Stanton, Anthony, and Stone to establish the American Equal Rights Association. The following year, the organization became active in Kansas where black suffrage and woman suffrage were to be decided by popular vote, and it was then that Stanton and Anthony formed a political alliance with Train, leading to Mott's resignation. Kansas failed to pass both referendums.

Mott was a founder and president of the Northern Association for the Relief and Employment of Poor Women in Philadelphia (founded in 1846).

Seneca Falls Convention

In 1848, Mott and Cady Stanton organized the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, at Seneca Falls, New York. Stanton's resolution that it was "the duty of the women of this country to secure to themselves the sacred right to the elective franchise" was passed despite Mott's opposition. Mott viewed politics as corrupted by slavery and moral compromises, but she soon concluded that women's "right to the elective franchise however, is the same, and should be yielded to her, whether she exercises that right or not." Mott signed the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments. Despite Mott's opposition to electoral politics, her fame had reached into the political arena even before the July 1848 women's rights convention. During the June 1848 National Convention of the Liberty Party, 5 of the 84 voting delegates cast their ballots for Lucretia Mott to be their party's candidate for the Office of U.S. Vice President. In delegate voting, she placed 4th in a field of nine. Over the next few decades, women's suffrage became the focus of the women's rights movement. While Cady Stanton is usually credited as the leader of that effort, it was Mott's mentoring of Cady Stanton and their work together that inspired the event. Mott's sister,Martha Coffin Wright

Martha Coffin Wright (December 25, 1806 – 1875) was an American feminist, abolitionist, and signatory of the Declaration of Sentiments who was a close friend and supporter of Harriet Tubman.

Early life

Martha Coffin was born in Boston, Mass ...

, also helped organize the convention and signed the declaration.

Noted abolitionist and human rights activist Frederick Douglass was in attendance and played a key role in persuading the other attendees to agree to a resolution calling for women's suffrage.

''Sermon to the Medical Students''

The biological justifications of race as a biologically provable basis for difference gave rise to the stigma of innate, naturally determined inferiority in the 19th century. In 1849, Mott's "Sermon to the Medical Students" was published:"May you be faithful, and enter into a consideration as to how far you are partakers in this evil, even in other men's sins. How far, by permission, by apology, or otherwise, you are found lending your sanction to a system which degrades and brutalizes three million of our fellow beings."

''Discourse on Women''

In 1850, Mott published her speech ''Discourse on Woman'', a pamphlet about restrictions on women in the United States.American Equal Rights Association

After the Civil War, Mott was elected the first president of the American Equal Rights Association, an organization that advocated universal suffrage. She resigned from the association in 1868 when

After the Civil War, Mott was elected the first president of the American Equal Rights Association, an organization that advocated universal suffrage. She resigned from the association in 1868 when Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

and Susan B. Anthony allied with a controversial businessman named George Francis Train

George Francis Train (March 24, 1829 – January 18, 1904) was an American entrepreneur who organized the clipper ship line that sailed around Cape Horn to San Francisco; he also organized the Union Pacific Railroad and the Credit Mobilier in th ...

. Mott tried to reconcile the two factions that split the following year over the priorities of woman suffrage and Black male suffrage. Ever the peacemaker, Mott tried to heal the breach between Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone

Lucy Stone (August 13, 1818 – October 18, 1893) was an American orator, abolitionist and suffragist who was a vocal advocate for and organizer promoting rights for women. In 1847, Stone became the first woman from Massachusetts to earn a colle ...

over the immediate goal of the women's movement: suffrage for freedmen and all women, or suffrage for freedmen first?

Swarthmore College

In 1864, Mott and several other Hicksite Quakers incorporatedSwarthmore College

Swarthmore College ( , ) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania. Founded in 1864, with its first classes held in 1869, Swarthmore is one of the earliest coeduca ...

near Philadelphia, which remains one of the premier liberal arts college

A liberal arts college or liberal arts institution of higher education is a college with an emphasis on undergraduate study in liberal arts and sciences. Such colleges aim to impart a broad general knowledge and develop general intellectual capac ...

s in the country.

Pacifism

Mott was a pacifist, and in the 1830s, she attended meetings of theNew England Non-Resistance Society The New England Non-Resistance Society was an American peace group founded at a special peace convention organized by William Lloyd Garrison, in Boston in September 1838.Peter Brock ''Pacifism in the United States, from the Colonial era to the First ...

. She opposed the War with Mexico. After the Civil War, Mott increased her efforts to end war and violence, and she was a leading voice in the Universal Peace Union The Universal Peace Union was a pacifist organization founded by former members of the American Peace Society in Providence, Rhode Island with the adoption of its constitution on 16 May 1866; it was chartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 9 Apri ...

, founded in 1866.

Personal life

On April 10, 1811, Lucretia Coffin married James Mott at Pine Street Meeting in Philadelphia. They had six children. Their second child, Thomas Mott, died at age two. Their surviving children all became active in the anti-slavery and other reform movements, following in their parents' paths. Her great-granddaughter

On April 10, 1811, Lucretia Coffin married James Mott at Pine Street Meeting in Philadelphia. They had six children. Their second child, Thomas Mott, died at age two. Their surviving children all became active in the anti-slavery and other reform movements, following in their parents' paths. Her great-granddaughter May Hallowell Loud

Maria "May" Mott Hallowell Loud (August 22, 1860 - February 1, 1916) was an American artist, suffragist, and member of the Hallowell family.

Family and personal life

Maria Mott Hallowell, known as "May", was born in 1860 in Medford, Massachuse ...

became an artist.

Mott died on November 11, 1880 of pneumonia at her home, Roadside, in the district now known as La Mott, Cheltenham, Pennsylvania

Cheltenham is an unincorporated area, unincorporated community in Cheltenham Township, Pennsylvania, United States, with a ZIP code of 19012. It is located directly over the city line (Cheltenham Avenue) of Philadelphia. It also borders Northeast ...

. She was buried near to the highest point of Fair Hill Burial Ground

Fair Hill Burial Ground is a historic cemetery in the Fairhill neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Founded by the Religious Society of Friends in 1703, it fell into disuse until the 1840s when it was revived by the Hicksite Quaker communi ...

, a Quaker cemetery in North Philadelphia.

Mott's great-granddaughter served briefly as the Italian interpreter for American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

Betty Friedan during a controversial speaking engagement in Rome.

Legacy

Susan Jacoby

Susan Jacoby (; born June 4, 1945) is an American author. Her 2008 book about American anti-intellectualism, ''The Age of American Unreason'', was a ''New York Times'' best seller. She is an atheist and a secularist. Jacoby graduated from Michiga ...

writes, "When Mott died in 1880, she was widely judged by her contemporaries... as the greatest American woman of the nineteenth century." She was a mentor to Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

, who continued her work.

A version of the Equal Rights Amendment

The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) is a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution designed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex. Proponents assert it would end legal distinctions between men and ...

from 1923, which differs from the current text, was named the Lucretia Mott Amendment. That draft read, "Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation."

The Camp Town section of Cheltenham Township, Pennsylvania, which was the site of Camp William Penn, and of Mott's home, Roadside, was renamed La Mott in her honor in 1885.

The United States Post Office issued a stamp in 1948 on the centennial of the Seneca Falls Convention, featuring Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

, Carrie Chapman Catt, and Lucretia Mott.

In 1983, Mott was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame

The National Women's Hall of Fame (NWHF) is an American institution incorporated in 1969 by a group of men and women in Seneca Falls, New York, although it did not induct its first enshrinees until 1973. As of 2021, it had 303 inductees.

Induc ...

.

Mott is commemorated along with Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

and Susan B. Anthony in '' Portrait Monument'', a 1921 sculpture by Adelaide Johnson at the United States Capitol. Originally kept on display in the crypt of the US Capitol, the sculpture was moved to its current location and more prominently displayed in the rotunda in 1997.

The Lucretia Mott School in Washington D.C. was named for her, as was P.S. 215 Lucretia Mott, in Queens, New York City; the latter closed in 2015.

The U.S. Treasury Department announced in 2016 that an image of Mott will appear on the back of a newly designed $10 bill along with Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth (; born Isabella Baumfree; November 26, 1883) was an American abolitionist of New York Dutch heritage and a women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to f ...

, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (November 12, 1815 – October 26, 1902) was an American writer and activist who was a leader of the women's rights movement in the U.S. during the mid- to late-19th century. She was the main force behind the 1848 Seneca ...

, Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ...

and the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession

The Woman Suffrage Procession on 3 March 1913 was the first suffragist parade in Washington, D.C. It was also the first large, organized march on Washington for political purposes. The procession was organized by the suffragists Alice Paul and ...

. Designs for new $5, $10 and $20 bills will be unveiled in 2020 in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of American women winning the right to vote via the Nineteenth Amendment.

See also

* History of feminism *Jane Johnson (slave)

Jane Johnson (c. 1814-1827 – August 2, 1872) lynn, Katherine E. "Jane Johnson Found! But Is She 'Hannah Crafts'? The Search for the Author of The Bondswoman's Narrative" ''National Genealogical Society Quarterly,'' September 2002 was an ...

* List of suffragists and suffragettes

* List of civil rights leaders

*Suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

* Women's Social and Political Union

* Women's suffrage in the United States

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * *Lucretia Coffin Mott

''Discourse on woman'', 1849 (From a book, Chapter 6, without pagination, continuous text), in google books

External links

Lucretia Mott

Women's Rights, National Historical Park, New York, National Park Service

* Th

Mott Manuscripts

held a

Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Mott, Lucretia 1793 births 1880 deaths 19th-century American women writers 19th-century Quakers American abolitionists American anti-war activists American Christian pacifists American Quakers American social reformers American suffragists Quaker abolitionists Deaths from pneumonia in Pennsylvania Political activists from Pennsylvania People from Cheltenham, Pennsylvania People from Nantucket, Massachusetts Quaker ministers University and college founders Underground Railroad in Pennsylvania Quaker feminists Women civil rights activists