Luca Gentili Ridolfucci on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share

A

A

The LUCA certainly had

The LUCA certainly had  An alternative to the search for "universal" traits is to use genome analysis to identify phylogenetically ancient genes. This gives a picture of a LUCA that could live in a geochemically harsh environment and is like modern prokaryotes. Analysis of biochemical pathways implies the same sort of chemistry as does phylogenetic analysis. Weiss and colleagues write that "Experiments ... demonstrate that ... acetyl-CoA pathway hemicals used in anaerobic respiration

An alternative to the search for "universal" traits is to use genome analysis to identify phylogenetically ancient genes. This gives a picture of a LUCA that could live in a geochemically harsh environment and is like modern prokaryotes. Analysis of biochemical pathways implies the same sort of chemistry as does phylogenetic analysis. Weiss and colleagues write that "Experiments ... demonstrate that ... acetyl-CoA pathway hemicals used in anaerobic respiration

The most commonly accepted

The most commonly accepted

common descent

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal comm ...

—the most recent common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; the origins of virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es are unclear but they share the same genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

. LUCA probably harboured a variety of viruses. The LUCA is not the first life on Earth, but rather the latest form ancestral to all existing life.

While there is no specific fossil evidence of the LUCA, the detailed biochemical similarity of all current life confirms its existence. Its characteristics can be inferred from shared features of modern genomes. These genes describe a complex life form with many co-adapted In biology, co-adaptation is the process by which two or more species, genes or phenotypic traits undergo adaptation as a pair or group. This occurs when two or more interacting characteristics undergo natural selection together in response to the s ...

features, including transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

and translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

mechanisms to convert information from DNA to RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

to protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s. The LUCA probably lived in the high-temperature water of deep sea vents near ocean-floor magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

flows around 4 billion years ago.

Historical background

A

A phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

directly portrays the idea of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

by descent from a single ancestor. An early tree of life was sketched by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December 1829), often known simply as Lamarck (; ), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier. He was an early proponent of the idea that biologi ...

in his ''Philosophie zoologique

''Philosophie zoologique'' ("Zoological Philosophy, or Exposition with Regard to the Natural History of Animals") is an 1809 book by the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, in which he outlines his pre-Darwinian theory of evolution, part of ...

'' in 1809. Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

more famously proposed the theory of universal common descent through an evolutionary process in his book ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' in 1859: "Therefore I should infer from analogy that probably all the organic beings which have ever lived on this earth have descended from some one primordial form, into which life was first breathed." The last sentence of the book begins with a restatement of the hypothesis:

: "There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one ..."

The term "last universal common ancestor" or "LUCA" was first used in the 1990s for such a primordial organism.

Inferring LUCA's features

An anaerobic thermophile

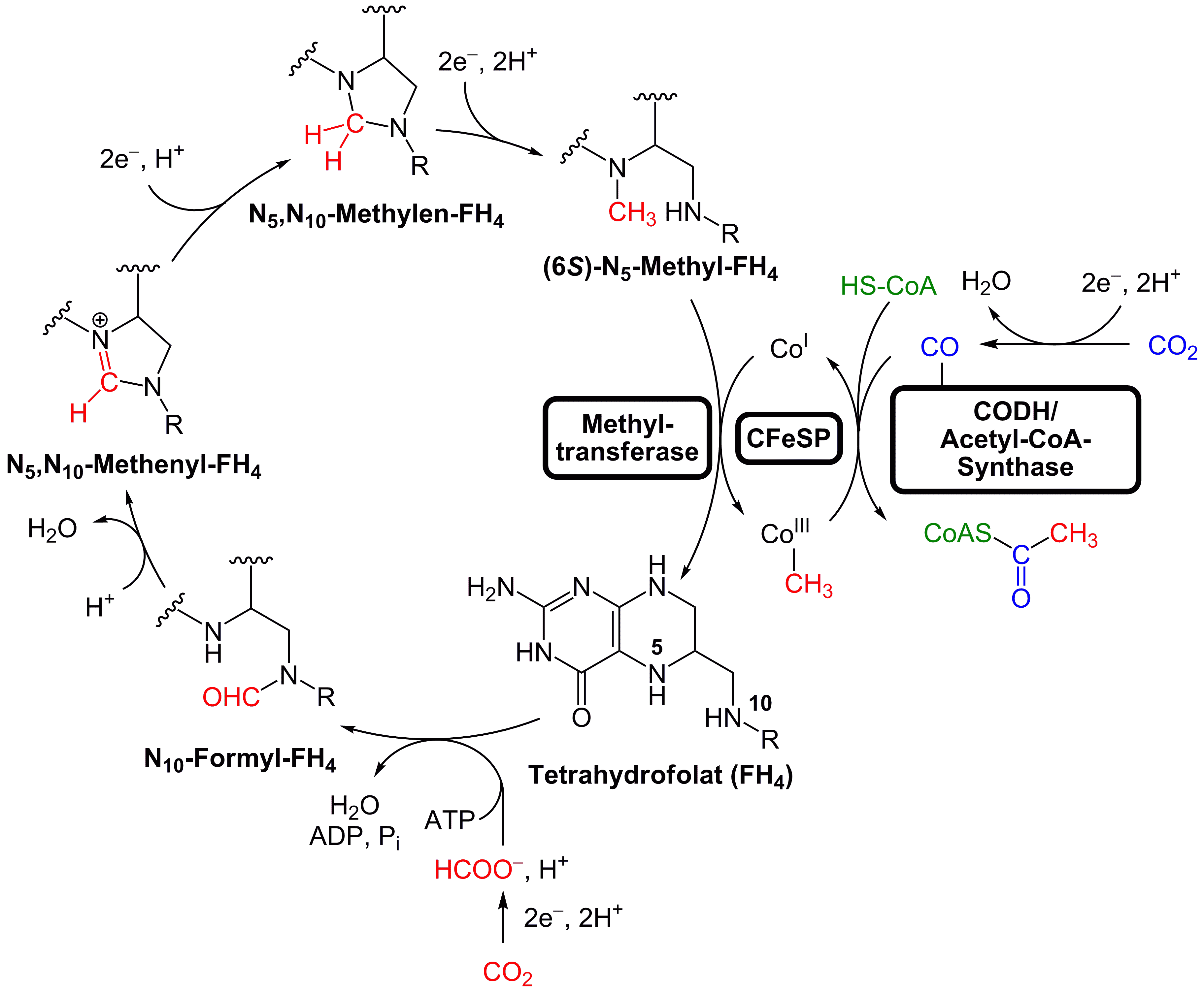

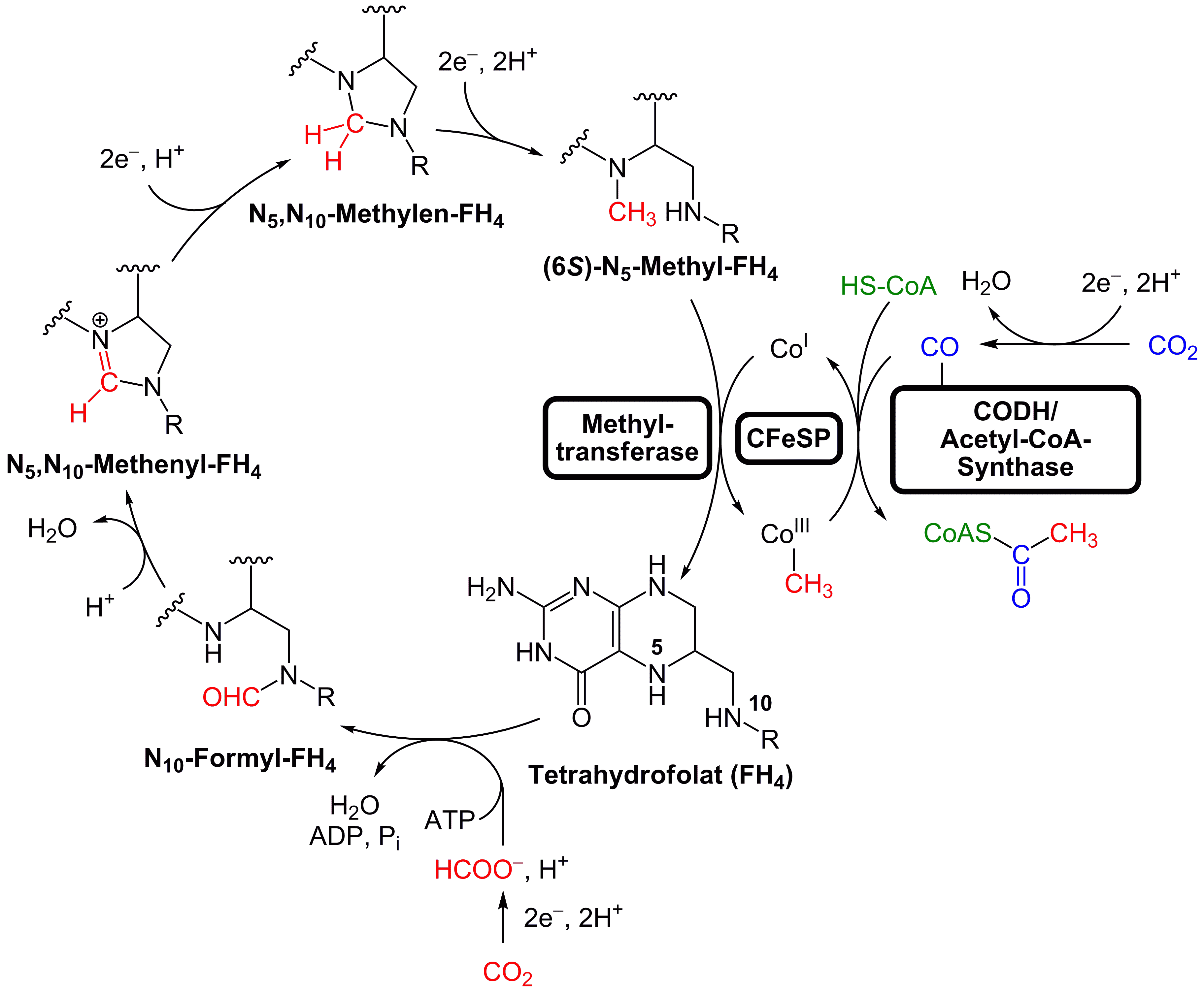

In 2016, Madeline C. Weiss and colleagues genetically analyzed 6.1 million protein-coding genes and 286,514 protein clusters from sequencedprokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a Unicellular organism, single-celled organism that lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek language, Greek wikt:πρό#Ancient Greek, πρό (, 'before') a ...

genomes representing many phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree (also phylogeny or evolutionary tree Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.) is a branching diagram or a tree showing the evolutionary relationships among various biological spec ...

s, and identified 355 protein clusters that were probably common to the LUCA. The results "depict LUCA as anaerobic

Anaerobic means "living, active, occurring, or existing in the absence of free oxygen", as opposed to aerobic which means "living, active, or occurring only in the presence of oxygen." Anaerobic may also refer to:

* Anaerobic adhesive, a bonding a ...

, CO2-fixing, H2-dependent with a Wood–Ljungdahl pathway

The Wood–Ljungdahl pathway is a set of biochemical reactions used by some bacteria. It is also known as the reductive acetyl-coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) pathway. This pathway enables these organisms to use hydrogen as an electron donor, and carb ...

(the reductive acetyl-coenzyme A

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for ...

pathway), N2-fixing and thermophilic

A thermophile is an organism—a type of extremophile—that thrives at relatively high temperatures, between . Many thermophiles are archaea, though they can be bacteria or fungi. Thermophilic eubacteria are suggested to have been among the earl ...

. LUCA's biochemistry was replete with FeS

Fez or Fes (; ar, فاس, fās; zgh, ⴼⵉⵣⴰⵣ, fizaz; french: Fès) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fès-Meknès administrative region. It is the second largest city in Morocco, with a population of 1.11 mi ...

clusters and radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

reaction mechanisms." The cofactors

Cofactor may also refer to:

* Cofactor (biochemistry), a substance that needs to be present in addition to an enzyme for a certain reaction to be catalysed

* A domain parameter in elliptic curve cryptography, defined as the ratio between the order ...

also reveal "dependence upon transition metal

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. They are the elements that can ...

s, flavins

Flavins (from Latin ''flavus'', "yellow") are organic compounds, like their base, pteridine. They are formed by the tricyclic heterocycle isoalloxazine. The biochemical source is the vitamin riboflavin. The flavin moiety is often attached with a ...

, S-adenosyl methionine

''S''-Adenosyl methionine (SAM), also known under the commercial names of SAMe, SAM-e, or AdoMet, is a common cosubstrate involved in methyl group transfers, transsulfuration, and aminopropylation. Although these anabolic reactions occur throug ...

, coenzyme A

Coenzyme A (CoA, SHCoA, CoASH) is a coenzyme, notable for its role in the synthesis and oxidation of fatty acids, and the oxidation of pyruvate in the citric acid cycle. All genomes sequenced to date encode enzymes that use coenzyme A as a subs ...

, ferredoxin

Ferredoxins (from Latin ''ferrum'': iron + redox, often abbreviated "fd") are iron–sulfur proteins that mediate electron transfer in a range of metabolic reactions. The term "ferredoxin" was coined by D.C. Wharton of the DuPont Co. and applied t ...

, molybdopterin

Molybdopterins are a class of cofactors found in most molybdenum-containing and all tungsten-containing enzymes. Synonyms for molybdopterin are: MPT and pyranopterin-dithiolate. The nomenclature for this biomolecule can be confusing: Molybdopter ...

, corrin

Corrin is a heterocyclic compound. It is the parent macrocycle related to the substituted derivative that is found in vitamin B12. Its name reflects that it is the "core" of vitamin B12 (cobalamins).Nelson, D. L.; Cox, M. M. "Lehninger, Princ ...

s and selenium

Selenium is a chemical element with the symbol Se and atomic number 34. It is a nonmetal (more rarely considered a metalloid) with properties that are intermediate between the elements above and below in the periodic table, sulfur and tellurium, ...

. Its genetic code required nucleoside

Nucleosides are glycosylamines that can be thought of as nucleotides without a phosphate group. A nucleoside consists simply of a nucleobase (also termed a nitrogenous base) and a five-carbon sugar (ribose or 2'-deoxyribose) whereas a nucleotide ...

modifications and S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methylation

In the chemical sciences, methylation denotes the addition of a methyl group on a substrate, or the substitution of an atom (or group) by a methyl group. Methylation is a form of alkylation, with a methyl group replacing a hydrogen atom. These t ...

s." The results are rather specific: they show that methanogen

Methanogens are microorganisms that produce methane as a metabolic byproduct in hypoxic conditions. They are prokaryotic and belong to the domain Archaea. All known methanogens are members of the archaeal phylum Euryarchaeota. Methanogens are com ...

ic clostridia

The Clostridia are a highly polyphyletic class of Bacillota, including '' Clostridium'' and other similar genera. They are distinguished from the Bacilli by lacking aerobic respiration. They are obligate anaerobes and oxygen is toxic to them. Sp ...

was basal, near the root of the phylogenetic tree, in the 355 protein lineages examined, and that the LUCA may therefore have inhabited an anaerobic hydrothermal vent

A hydrothermal vent is a fissure on the seabed from which geothermally heated water discharges. They are commonly found near volcanically active places, areas where tectonic plates are moving apart at mid-ocean ridges, ocean basins, and hotspot ...

setting in a geochemically active environment rich in H2, CO2, and iron,

where ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

water interacted with hot magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natural sa ...

beneath the ocean floor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

.

While the gross anatomy of the LUCA can only be reconstructed with much uncertainty, its biochemical mechanisms can be described in some detail, based on the "universal" properties currently shared by all independently living organisms on Earth.

gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

s and a genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

. Its genetic material was most likely DNA, so that it lived after the RNA world

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

. The DNA was kept double-stranded by an enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

, DNA polymerase

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create ...

, which recognises the structure and directionality of DNA. The integrity of the DNA was maintained by a group of repair

The technical meaning of maintenance involves functional checks, servicing, repairing or replacing of necessary devices, equipment, machinery, building infrastructure, and supporting utilities in industrial, business, and residential installa ...

enzymes including DNA topoisomerase

DNA topoisomerases (or topoisomerases) are enzymes that catalyze changes in the topological state of DNA, interconverting relaxed and supercoiled forms, linked (catenated) and unlinked species, and knotted and unknotted DNA. Topological issues i ...

. If the genetic code was based on dual-stranded DNA, it was expressed by copying the information to single-stranded RNA. The RNA was produced by a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that synthesizes RNA from a DNA template.

Using the enzyme helicase, RNAP locally opens the ...

using nucleotides similar to those of DNA. It had multiple DNA-binding protein

DNA-binding proteins are proteins that have DNA-binding domains and thus have a specific or general affinity for DNA#Base pairing, single- or double-stranded DNA. Sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins generally interact with the major groove ...

s, such as histone-fold proteins. The genetic code was expressed into protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s. These were assembled from 20 free amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s by translation

Translation is the communication of the Meaning (linguistic), meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The ...

of a messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the p ...

via a mechanism of ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s, transfer RNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

s, and a group of related proteins.

As for the cell's gross structure, it contained a water-based cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

effectively enclosed by a lipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many vir ...

membrane; it was capable of reproducing by cell division. It tended to exclude sodium

Sodium is a chemical element with the symbol Na (from Latin ''natrium'') and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 of the periodic table. Its only stable iso ...

and concentrate potassium

Potassium is the chemical element with the symbol K (from Neo-Latin ''kalium'') and atomic number19. Potassium is a silvery-white metal that is soft enough to be cut with a knife with little force. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmosphe ...

by means of specific ion transporter

In biology, a transporter is a transmembrane protein that moves ions (or other small molecules) across a biological membrane to accomplish many different biological functions including, cellular communication, maintaining homeostasis, energy produc ...

s (or ion pumps). The cell multiplied by duplicating all its contents followed by cellular division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there are ...

. The cell used chemiosmosis

Chemiosmosis is the movement of ions across a semipermeable membrane bound structure, down their electrochemical gradient. An important example is the formation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by the movement of hydrogen ions (H+) across a membra ...

to produce energy. It also reduced CO2 and oxidized H2 (methanogenesis

Methanogenesis or biomethanation is the formation of methane coupled to energy conservation by microbes known as methanogens. Organisms capable of producing methane for energy conservation have been identified only from the domain Archaea, a group ...

or acetogenesis Acetogenesis is a process through which acetate is produced either by the reduction of CO2 or by the reduction of organic acids, rather than by the oxidative breakdown of carbohydrates or ethanol, as with acetic acid bacteria.

The different bacte ...

) via acetyl

In organic chemistry, acetyl is a functional group with the chemical formula and the structure . It is sometimes represented by the symbol Ac (not to be confused with the element actinium). In IUPAC nomenclature, acetyl is called ethanoyl, ...

-thioester

In organic chemistry, thioesters are organosulfur compounds with the functional group . They are analogous to carboxylate esters () with the sulfur in the thioester playing the role of the linking oxygen in the carboxylate ester, as implied by t ...

s.

By phylogenetic bracketing

Phylogenetic bracketing is a method of inference used in biological sciences. It is used to infer the likelihood of unknown traits in organisms based on their position in a phylogenetic tree. One of the main applications of phylogenetic bracketing ...

, analysis of the presumed LUCA's offspring groups, LUCA appears to have been a small, single-celled organism. It likely had a ring-shaped coil of DNA floating freely within the cell. Morphologically, it would likely not have stood out within a mixed population of small modern-day bacteria. The originator of the three-domain system

The three-domain system is a biological classification introduced by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler, and Mark Wheelis in 1990 that divides cellular life forms into three domains, namely Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukaryota or Eukarya. The key difference fr ...

, Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese (; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal RNA, ...

, stated that in its genetic machinery, the LUCA would have been a "simpler, more rudimentary entity than the individual ancestors that spawned the three omains(and their descendants)".

An alternative to the search for "universal" traits is to use genome analysis to identify phylogenetically ancient genes. This gives a picture of a LUCA that could live in a geochemically harsh environment and is like modern prokaryotes. Analysis of biochemical pathways implies the same sort of chemistry as does phylogenetic analysis. Weiss and colleagues write that "Experiments ... demonstrate that ... acetyl-CoA pathway hemicals used in anaerobic respiration

An alternative to the search for "universal" traits is to use genome analysis to identify phylogenetically ancient genes. This gives a picture of a LUCA that could live in a geochemically harsh environment and is like modern prokaryotes. Analysis of biochemical pathways implies the same sort of chemistry as does phylogenetic analysis. Weiss and colleagues write that "Experiments ... demonstrate that ... acetyl-CoA pathway hemicals used in anaerobic respirationformate

Formate (IUPAC name: methanoate) is the conjugate base of formic acid. Formate is an anion () or its derivatives such as ester of formic acid. The salts and esters are generally colorless.Werner Reutemann and Heinz Kieczka "Formic Acid" in ''Ull ...

, methanol

Methanol (also called methyl alcohol and wood spirit, amongst other names) is an organic chemical and the simplest aliphatic alcohol, with the formula C H3 O H (a methyl group linked to a hydroxyl group, often abbreviated as MeOH). It is a ...

, acetyl

In organic chemistry, acetyl is a functional group with the chemical formula and the structure . It is sometimes represented by the symbol Ac (not to be confused with the element actinium). In IUPAC nomenclature, acetyl is called ethanoyl, ...

moieties, and even pyruvate

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic aci ...

arise spontaneously ... from CO2, native metals, and water", a combination present in hydrothermal vents.

Alternative interpretations

Some other researchers have challenged Weiss et al.'s 2016 conclusions. Sarah Berkemer and Shawn McGlynn argue that Weiss et al. undersampled the families of proteins, so that the phylogenetic trees were not complete and failed to describe the evolution of proteins correctly. A phylogenomic and geochemical analysis of a set of proteins that probably traced to the LUCA show that it had K+-dependent GTPases and the ionic composition and concentration of its intracellular fluid was seemingly high K+/Na+ ratio, , Fe2+, CO2+, Ni2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, pyrophosphate, and which would imply a terrestrialhot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

habitat. It possibly had a phosphate-based metabolism. Further, these proteins were unrelated to autotroph

An autotroph or primary producer is an organism that produces complex organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) using carbon from simple substances such as carbon dioxide,Morris, J. et al. (2019). "Biology: How Life Works", ...

y (the ability of an organism to create its own organic matter

Organic matter, organic material, or natural organic matter refers to the large source of carbon-based compounds found within natural and engineered, terrestrial, and aquatic environments. It is matter composed of organic compounds that have c ...

), suggesting that the LUCA had a heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

ic lifestyle (consuming organic matter) and that its growth was dependent on organic matter produced by the physical environment. Nick Lane argues that Na+/H+ antiporters could readily explain the low concentration of Na+ in the LUCA and its descendants.

The identification of thermophilic genes in the LUCA has also been criticized, as they may instead represent genes that evolved later in archaea or bacteria, then migrated between these via horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

s, as in Woese's 1998 hypothesis. Further, the presence of the energy-handling enzymes CODH/acetyl-coenzyme A

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized for ...

synthase in LUCA could be compatible not only with being an autotroph

An autotroph or primary producer is an organism that produces complex organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins) using carbon from simple substances such as carbon dioxide,Morris, J. et al. (2019). "Biology: How Life Works", ...

but also with life as a mixotroph A mixotroph is an organism that can use a mix of different sources of energy and carbon, instead of having a single trophic mode on the continuum from complete autotrophy at one end to heterotrophy at the other. It is estimated that mixotrophs comp ...

or heterotroph

A heterotroph (; ) is an organism that cannot produce its own food, instead taking nutrition from other sources of organic carbon, mainly plant or animal matter. In the food chain, heterotrophs are primary, secondary and tertiary consumers, but ...

. Weiss et al. 2018 reply that no enzyme defines a trophic lifestyle, and that heterotrophs evolved from autotrophs.

Age

Studies from 2000 to 2018 have suggested an increasingly ancient time for the LUCA. In 2000, estimates of the LUCA's age ranged from 3.5 to 3.8 billion years ago in thePaleoarchean

The Paleoarchean (), also spelled Palaeoarchaean (formerly known as early Archean), is a Geologic time scale#Terminology, geologic era within the Archean, Archaean Eon. The name derives from Greek "Palaios" ''ancient''. It spans the period of time ...

, a few hundred million years before the earliest fossil evidence of life, for which candidates range in age from 3.48 to 4.28 billion years ago. This placed the LUCA shortly after the Late Heavy Asteroid Bombardment which was thought to have repeatedly sterilized Earth's surface.

However, a 2018 study from the University of Bristol

, mottoeng = earningpromotes one's innate power (from Horace, ''Ode 4.4'')

, established = 1595 – Merchant Venturers School1876 – University College, Bristol1909 – received royal charter

, type ...

, applying a molecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleoti ...

model, found that the data (102 species, 29 common protein-coding genes, mostly ribosomal) is compatible only with LUCA as early as within 0.05 billion years of the maximum possible age given by the Earth-sterilizing Moon-forming event about 4.5 billion years ago.

Root of the tree of life

tree of life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythological, religious, and philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A History ...

, based on several molecular studies, has its root between a monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gro ...

domain

Domain may refer to:

Mathematics

*Domain of a function, the set of input values for which the (total) function is defined

**Domain of definition of a partial function

**Natural domain of a partial function

**Domain of holomorphy of a function

* Do ...

Bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

and a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

formed by Archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

and Eukaryota

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the ...

. A small minority of studies place the root in the domain bacteria, in the phylum Bacillota

The Bacillota (synonym Firmicutes) are a phylum of bacteria, most of which have gram-positive cell wall structure. The renaming of phyla such as Firmicutes in 2021 remains controversial among microbiologists, many of whom continue to use the earl ...

, or state that the phylum Chloroflexota

The Chloroflexota are a phylum of bacteria containing isolates with a diversity of phenotypes, including members that are aerobic thermophiles, which use oxygen and grow well in high temperatures; anoxygenic phototrophs, which use light for photo ...

(formerly Chloroflexi) is basal to a clade with Archaea and Eukaryotes and the rest of bacteria (as proposed by Thomas Cavalier-Smith

Thomas (Tom) Cavalier-Smith, FRS, FRSC, NERC Professorial Fellow (21 October 1942 – 19 March 2021), was a professor of evolutionary biology in the Department of Zoology, at the University of Oxford.

His research has led to discov ...

). Recent genomic analyses recover a two-domain system with the domains Archaea and Bacteria; in this view of the tree of life, Eukaryotes are derived from Archaea.

With the later gene pool of the LUCA's descendants, sharing a common framework of the AT/GC rule and the standard twenty amino acids, horizontal gene transfer would have become feasible and could have been common. In 1998, Carl Woese

Carl Richard Woese (; July 15, 1928 – December 30, 2012) was an American microbiologist and biophysicist. Woese is famous for defining the Archaea (a new domain of life) in 1977 through a pioneering phylogenetic taxonomy of 16S ribosomal RNA, ...

proposed that no individual organism could be considered a LUCA, and that the genetic heritage of all modern organisms derived through horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between Unicellular organism, unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offsprin ...

among an ancient community of organisms. Other authors concur that there was a "complex collective genome" at the time of the LUCA, and that horizontal gene transfer was important in the evolution of later groups; Nicolas Glansdorff states that "Of course, LUCA was not living alone at that time (as the African Eve

In human genetics, the Mitochondrial Eve (also ''mt-Eve, mt-MRCA'') is the matrilineal most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all living humans. In other words, she is defined as the most recent woman from whom all living humans descend in an un ...

herself) but among many other organisms that have no descendants today." In 2010, based on "the vast array of molecular sequences now available from all domains of life," a " formal test" of universal common ancestry was published. The formal test favored the existence of a universal common ancestor over a wide class of alternative hypotheses that included horizontal gene transfer. Basic biochemical principles make it overwhelmingly likely that all organisms do have a single common ancestor. While the test overwhelmingly favored the existence of a single LUCA, this does not imply that the LUCA was ever alone: Instead, it was the only cell whose descendants survived beyond the Paleoarchean

The Paleoarchean (), also spelled Palaeoarchaean (formerly known as early Archean), is a Geologic time scale#Terminology, geologic era within the Archean, Archaean Eon. The name derives from Greek "Palaios" ''ancient''. It spans the period of time ...

, outcompeting all others.

LUCA's viruses

Based on howvirus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

es are currently distributed across the bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

and archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebac ...

, the LUCA may well have been prey to multiple viruses, ancestral to those that now have those two domains as their hosts. further, extensive virus evolution seems to have preceded the LUCA, since the jelly-roll structure of capsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

proteins is shared by RNA and DNA viruses across all three domains of life. LUCA's viruses were probably mainly dsDNA viruses in the groups called ''Duplodnaviria

''Duplodnaviria'' is a realm of viruses that includes all double-stranded DNA viruses that encode the HK97 fold major capsid protein. The HK97 fold major capsid protein (HK97 MCP) is the primary component of the viral capsid, which stores the v ...

'' and ''Varidnaviria

''Varidnaviria'' is a realm of viruses that includes all DNA viruses that encode major capsid proteins that contain a vertical jelly roll fold. The major capsid proteins (MCP) form into pseudohexameric subunits of the viral capsid, which stores t ...

''. Two other single-stranded DNA virus

A DNA virus is a virus that has a genome made of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) that is replicated by a DNA polymerase. They can be divided between those that have two strands of DNA in their genome, called double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses, and t ...

groups within the ''Monodnaviria

''Monodnaviria'' is a realm of viruses that includes all single-stranded DNA viruses that encode an endonuclease of the HUH superfamily that initiates rolling circle replication of the circular viral genome. Viruses descended from such viruses a ...

'', the ''Microviridae

''Microviridae'' is a family of bacteriophages with a single-stranded DNA genome. The name of this family is derived from the ancient Greek word (), meaning "small". This refers to the size of their genomes, which are among the smallest of the ...

'' and the ''Tubulavirales

''Tubulavirales'' is an order of viruses.

Taxonomy

The following families are recognized:

* ''Inoviridae

Filamentous bacteriophage is a family of viruses (''Inoviridae'') that infect bacteria. The phages are named for their filamentous sha ...

'', likely infected the last bacterial common ancestor. The last archaeal common ancestor was probably host to spindle-shaped viruses. All of these could well have affected the LUCA, in which case each must since have been lost in the host domain where it is no longer extant.

By contrast, RNA viruses do not appear to have been important parasites of LUCA, even though straightforward thinking might have envisaged viruses as beginning with RNA viruses directly derived from an RNA world. Instead, by the time the LUCA lived, RNA viruses had probably already been out-competed by DNA viruses.

See also

* * *Darwinian threshold

Darwinian threshold or Darwinian transition is a term introduced by Carl Woese to describe a transition period during the evolution of the first Cell (biology), cells when Transmission (genetics), genetic transmission moves from a predominantly hor ...

- Transition period during the evolution of the first cells

*

*

*

*

Notes

References

Further reading

*External links

* {{Organisms et al. Origin of life Evolutionary biology Genetic genealogy Phylogenetics Hypothetical life forms Last common ancestors Events in biological evolution