Lower Mississippi Valley Yellow Fever Epidemic Of 1878 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In 1878, a severe

yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

epidemic swept through the lower Mississippi Valley

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

.

Events Leading Up to the Epidemic

During theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

was occupied with Union troops, and the local populace believed that yellow fever would only kill the northern troops. These rumors instilled fear into the Union troops, and they actively practiced sanitation and quarantine procedures during their occupation in 1862 until the government pulled federal troops out of the city in 1877. The withdrawal of Union troops resulted in the relaxation of sanitation and quarantine efforts in Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

. Following the yellow fever epidemic in Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Shreveport, Louisiana

Shreveport ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Louisiana. It is the third most populous city in Louisiana after New Orleans and Baton Rouge, respectively. The Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan area, with a population of 393,406 in 2020, is t ...

, where 769 people died between August and November, the states in the Lower Mississippi Valley began to take precautions for any following epidemics. After the epidemic in Shreveport, the Quarantine Act of 1878 was passed that allowed the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

federal government to assume control over the state in quarantines, but the law did not allow for the federal government to intercede on local medical authorities or health boards. In March of that year, a virulent strain of Yellow Fever was found in Havana, Cuba

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, and New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

health officials ordered the detainment of all vessels from the Cuban and Brazilian regions. It is unknown what exactly led to the outbreak in the Mississippi River Valley as causes range from unchecked vessels from the fruit trade to refugees from the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Ten Years' War

The Ten Years' War ( es, Guerra de los Diez Años; 1868–1878), also known as the Great War () and the War of '68, was part of Cuba's fight for independence from Spain. The uprising was led by Cuban-born planters and other wealthy natives. O ...

in Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

, which was experiencing a rise in yellow fever cases, however, investigations at the time suggest that the epidemic originated from the steamer ''Emily B. Souder'' on May 22, 1878.

Effects of the epidemic on the region

The entire Mississippi River Valley fromSt. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

south was affected, and tens of thousands fled the stricken cities of New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Vicksburg Vicksburg most commonly refers to:

* Vicksburg, Mississippi, a city in western Mississippi, United States

* The Vicksburg Campaign, an American Civil War campaign

* The Siege of Vicksburg, an American Civil War battle

Vicksburg is also the name of ...

, and Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

. The epidemic in the Lower Mississippi Valley also greatly affected trade in the region, with orders of steamboats to be tied up in order to reduce the amount of travel along the Mississippi River, railroad lines were halted, and all the workers to be laid off. Carrigan states that "An estimated 15,000 heads of households were unemployed in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, 8,000 in Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

, and several thousands more in scattered small towns - representing a total of over 100,000 persons in dire need."

New Orleans

When the epidemic broke out from the ''Emily B. Souder'' in May, roughly 40,000 residents that represent 20% of the city population fled the city, many of whom fled via the new railroads systems constructed during theReconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

period after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, which further spread the virus across the Lower Mississippi Valley. The city saw roughly 20,000 total infections during the epidemic with 5,000 resulting in deaths, and saw a loss of more than $15 million due to the disruptions in trade from the epidemic.

Due to the struggles of the remaining citizens, numerous organizations formed relief committees that relied heavily on aid from the federal government in the form of relief rations and money donations from unaffected cities in the Northern United States. The federal relief came with heavy restrictions, as they were only allowed to be given to households that had yellow fever and could provide proof via a doctor's certificate or given to people considered "destitute." These restrictions led to many citizens having to go without federal aid, resulting in roughly 10,000 people receiving aid despite there being 20,000 cases of yellow fever alone.

Memphis

Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

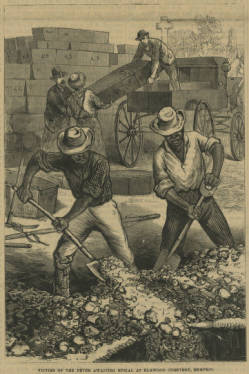

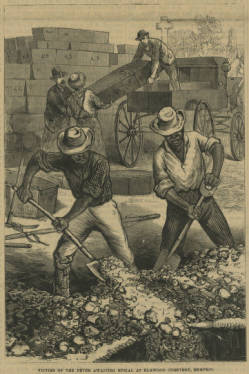

suffered several epidemics during the 1870s, culminating in the 1879 epidemic following the most severe bout of the fever, the 1878 wave. During this year, there were more than 5,000 fatalities in the city. Some contemporary accounts said that commercial interests had prevented the rapid reporting of the outbreak of the epidemic, increasing the total number of deaths. People still did not understand how the disease developed or was transmitted, and did not know how to prevent it.Crosby, M. C. (2006), ''The American Plague: The Untold Story of Yellow Fever, the Epidemic That Shaped Our History''.

These misconceptions regarding the mechanism of the virus exacerbated the rising death toll in Memphis as people operated under false notions of safety in the fever-ridden zones of the city. According to J.M. Keating, renowned for his highly-referenced history of the 1878 yellow fever epidemic in Memphis, his text underscores the lack of consensus among medical professionals at this time. He spends the first two chapters of his anthology explaining the conflicting theories regarding the epidemiology of the virus and makes no mention of what is now known to be the real culprit, the Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its legs ...

mosquito. Unknown to physicians at the time, yellow fever was spread through the bite of an infected mosquito which proliferated in warm, moist areas of high population density. Given its urban and largely unsanitary environment in a vital trading location on the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, Memphis became the ideal locale for the virus to take root after spreading from its origin in New Orleans.

Similar to the preventative measures taken in New Orleans was the implementation of the quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been ...

in Memphis. Once the spread of the virus to Memphis became imminent, a city-wide quarantine was instated which barred entry into the city. Unknown to public officials in Memphis, the virus had already arrived to the city by the time the quarantine went into effect, making this a futile approach to reducing spread. Beyond the quarantine, other common precautions included avoiding coming in contact with the “excreta” or bodily fluids of fever victims due to the misconception that the virus could be transferred through these liquids. While the impact of the mosquito remained unnoticed, ill-prepared citizens continued to operate unprotected under these poor defenses, adding to the ever-growing number of fever victims.

For those who wished to avoid the grip of the fever in the city, flight from Memphis was appealing to a majority of the city’s population. The news of deaths in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

and in the nearby town of Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Hickman

Hickman or Hickmann may refer to:

People

* Hickman (surname), notable people with the surname Hickman or Hickmann

* Hickman Ewing, American attorney

* Hickman Price (1911–1989), assistant secretary in the United States Department of Commerce

* ...

in August led to the mass withdrawal of an estimated 25,000 residents from the city of Memphis within four days, which led to further spread of the virus across the Lower Mississippi Valley. This exodus of a large proportion of the population of Memphis consisted primarily of those of the white Protestant class who possessed the means to leave the city for safety. Left behind were African American residents and a large circle of Irish Catholics who lacked the wealth to uproot from their homes located in the poorest sectors of town. The departure of white Protestants not only fueled the animosity that existed between the Catholics of the city and themselves, but also left Memphis ill-equipped in the manpower needed to sustain fever relief efforts. Consequently, the integral role Catholic clergy came to play in aiding fever victims was largely a product of the gap left by white Protestant flight.

In light of this reality, Catholic intervention in the path of the fever in Memphis becomes crucial to understanding the story of these devastating months. Catholic clergy opened their churches and convents to render aid on a non-discriminatory basis, aiding a community that would have remained insufficiently aided otherwise. Despite their extensive service during the epidemic years in Memphis, the involvement of Catholic clergy in fever relief efforts has largely gone undocumented. No explanation for their absence from fever records is confirmed. However, the death the Catholic community experienced was a blow from which their population would never recover, effecting a change in the character of Memphis felt deeply in the years after the fever had run its course.

In addition to extensive mortality, Memphis also saw an economic crisis during the epidemic, where trade was halted entirely in the city, and the lack of commerce led to mass starvations throughout the city, inciting riots and looting. All in all, Ellis states that " of the approximately 20,000 persons remaining in the city, an estimated 17,000 contracted the fever, of whom 5,150 died. There were at least 11,000 cases among 14,000 blacks, resulting in 946 deaths. By contrast, virtually all of the 6,000 whites were stricken, and 4,204 cases proved fatal. The disaster's economic cost to the city was later calculated to be upward of fifteen million dollars."

Mississippi

The 1878 epidemic was the worst that occurred in the state ofMississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. Sometimes known as "Yellow Jack", and "Bronze John", devastated Mississippi socially and economically. Entire families were killed, while others fled their homes for the presumed safety of other parts of the state. Quarantine regulations, passed to prevent the spread of the disease, brought trade to a stop. Some local economies never recovered. Beechland, near Vicksburg, became a ghost town because of the epidemic. By the end of the year, 3,227 people had died from the disease.

In the town of Grenada located in northern Mississippi, about 1,000 people of the town's population fled while the remaining population suffered "approximately 1,050 cases and 350 deaths." The town was a known railroad town, and it was found that the refugees from railroad towns often spread the illness with them along the railroads.

Aftermath

The epidemic lasted until late October when lower temperatures drove off the '' A. Aegypti'' mosquitoes, the primary carrier of yellow fever, away or into hibernation. It was not until November 19 when the epidemic was officially declared to be over. Ellis states that "according to estimates, there were around 120,000 cases of yellow fever and approximately 20,000 deaths." The Lower Mississippi Valley also experienced roughly $30 million in economic losses due to the disruption of commerce caused by the epidemic.References

{{Epidemics 1878 natural disasters in the United States 1878 disease outbreaks 19th-century epidemics Yellow fever Disease outbreaks in the United States Mississippi River