Louis MacNeice on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

MacNeice was awarded the

MacNeice was awarded the

* ''I Crossed the Minch'' (1938, travel, prose and verse)

* ''Modern Poetry: A Personal Essay'' (1938, criticism)

* ''

* ''I Crossed the Minch'' (1938, travel, prose and verse)

* ''Modern Poetry: A Personal Essay'' (1938, criticism)

* ''

Louis MacNeice Papers

at the

Local Writing Legends – Louis MacNeice

at bbc.co.uk

Profile at the Poetry Archive

Profile at Poets.org

Profile at Poetry Foundation

MacNeice at portraits at National Portrait Gallery

* Arthur Strain

"Writer's life celebrated"

BBC News, 12 September 2007. Text and audio file.

Louis MacNeice Memorial Programme

BBC Radio, 1963

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

Louis MacNeice collection, 1926-1959Finding aid to Louis MacNeice papers at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

{{DEFAULTSORT:MacNeice, Louis 1907 births 1963 deaths Academics of Bedford College, London Academics of the University of Birmingham Alumni of Merton College, Oxford Anglicans from Northern Ireland Classical scholars of the University of Birmingham Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Formalist poets Male poets from Northern Ireland People educated at Marlborough College Prix Italia winners 20th-century British male writers 20th-century Irish poets Translators of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Deaths from pneumonia in England

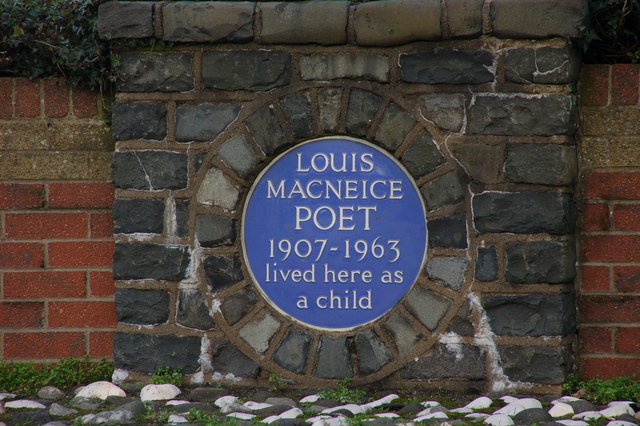

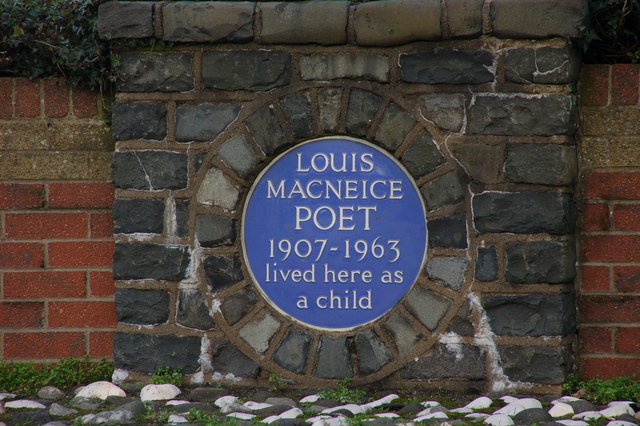

Frederick Louis MacNeice (12 September 1907 – 3 September 1963) was an Irish poet and playwright, and a member of the

Louis MacNeice (known as Freddie until his teens, when he adopted his middle name) was born in

Louis MacNeice (known as Freddie until his teens, when he adopted his middle name) was born in

Both were originally from the West of Ireland. MacNeice's father, an

.

Auden Group

The Auden Group or the Auden Generation is a group of British and Irish writers active in the 1930s that included W. H. Auden, Louis MacNeice, Cecil Day-Lewis, Stephen Spender, Christopher Isherwood, and sometimes Edward Upward and Rex Warner. ...

, which also included W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

, Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by the ...

and Cecil Day-Lewis. MacNeice's body of work was widely appreciated by the public during his lifetime, due in part to his relaxed but socially and emotionally aware style. Never as overtly or simplistically political as some of his contemporaries, he expressed a humane opposition to totalitarianism as well as an acute awareness of his roots.

Life

Ireland, 1907–1917

Louis MacNeice (known as Freddie until his teens, when he adopted his middle name) was born in

Louis MacNeice (known as Freddie until his teens, when he adopted his middle name) was born in Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

, the youngest son of Rev. John Frederick and Elizabeth Margaret ("Lily") MacNeice.Poetry Foundation profileBoth were originally from the West of Ireland. MacNeice's father, an

Anglican clergyman

The Anglican ministry is both the leadership and agency of Christian service in the Anglican Communion. "Ministry" commonly refers to the office of ordained clergy: the ''threefold order'' of bishops, priests and deacons. More accurately, Anglica ...

, would go on to become a bishop in the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

and his mother Elizabeth née Cleshan, from Ballymaconry, Connemara

Connemara (; )( ga, Conamara ) is a region on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of western County Galway, in the west of Ireland. The area has a strong association with traditional Irish culture and contains much of the Connacht Irish-speak ...

, County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

, had been a schoolmistress. The family moved to Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus ( , meaning " Fergus' rock") is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It sits on the north shore of Belfast Lough, from Belfast. The town had a population of 27,998 at the 2011 Census. It is County Antrim's oldest t ...

, County Antrim

County Antrim (named after the town of Antrim, ) is one of six counties of Northern Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. Adjoined to the north-east shore of Lough Neagh, the county covers an area of and has a population o ...

, soon after MacNeice's birth. When MacNeice was six, his mother was admitted to a Dublin nursing home suffering from severe clinical depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD), also known as clinical depression, is a mental disorder characterized by at least two weeks of pervasive low mood, low self-esteem, and loss of interest or pleasure in normally enjoyable activities. Intro ...

and he did not see her again. She survived uterine cancer

Uterine cancer, also known as womb cancer, includes two types of cancer that develop from the tissues of the uterus. Endometrial cancer forms from the lining of the uterus, and uterine sarcoma forms from the muscles or support tissue of the ut ...

but died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

in December 1914. MacNeice later described the cause of his mother's death as "obscure", and blamed his mother's cancer on his own difficult birth. His brother William, who had Down's syndrome

Down syndrome or Down's syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21. It is usually associated with physical growth delays, mild to moderate intellectual disa ...

, had been sent to live in an institution in Scotland during his mother's terminal illness. In 1917, his father remarried to Georgina Greer and MacNeice's sister Elizabeth was sent to board at a preparatory school at Sherborne

Sherborne is a market town and civil parish in north west Dorset, in South West England. It is sited on the River Yeo, on the edge of the Blackmore Vale, east of Yeovil. The parish includes the hamlets of Nether Coombe and Lower Clatcombe. ...

, England. MacNeice joined her at Sherborne Preparatory School later in the year.

School, 1917–1926

MacNeice was generally happy at Sherborne, which gave an education concentrating on theClassics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

(Greek and Latin) and literature (including the memorising of poetry). He was an enthusiastic sportsman, something which continued when he moved to Marlborough College

Marlborough College is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English Independent school (United Kingdom), independent boarding school) for pupils aged 13 to 18 in Marlborough, Wiltshire, England. Founded in 1843 for the sons of Church ...

in 1921, having won a classical scholarship. Marlborough was a less happy place, with a hierarchical and sometimes cruel social structure, but MacNeice's interest in ancient literature and civilisation deepened and expanded to include Egyptian

Egyptian describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of years of ...

and Norse mythology

Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia, and into the Nordic folklore of the modern period ...

. In 1922, he was invited to join Marlborough's secret 'Society of Amici' where he was a contemporary of John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman (; 28 August 190619 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of The Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture, ...

and Anthony Blunt, forming a lifelong friendship with the latter. He also wrote poetry and essays for the school magazines. By the end of his time at the school, MacNeice was sharing a study with Blunt and also sharing his aesthetic tastes, though not his sexual ones; Blunt said MacNeice was "totally, irredeemably heterosexual". In November 1925, MacNeice was awarded a postmastership to Merton College, Oxford

Merton College (in full: The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford) is one of the Colleges of Oxford University, constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. Its foundation can be traced back to the ...

, and he left Marlborough in the summer of the following year. He left behind his birth name of Frederick, his accent and his father's faith, although he never lost a sense of his Irishness; (the BBC radio premiere of MacNeice's '' The Dark Tower'' in January 1946, was preceded by the poet's ten-minute introduction in his distinctive Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

accent.)

Oxford, 1926–1930

It was during his first year as a student at Oxford that MacNeice first metW. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

, who had gained a reputation as the university's foremost poet during the preceding year. Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by the ...

and Cecil Day-Lewis were already part of Auden's circle, but MacNeice's closest Oxford friends were John Hilton, Christopher Holme and Graham Shepard

Graham Howard Shepard (1907–20 September 1943) was an English illustrator and cartoonist.

He was the son of Ernest H. Shepard, the illustrator of ''Winnie-the-Pooh'' and ''The Wind in the Willows''. He was educated at Marlborough College and ...

, who had been with him at Marlborough. MacNeice threw himself into the aesthetic culture, publishing poetry in literary magazines ''The Cherwell'' and ''Sir Galahad'', organising candle-lit readings of Shelley and Marlowe Marlowe may refer to:

Name

* Christopher Marlowe (1564–1593), English dramatist, poet and translator

* Philip Marlowe, fictional hardboiled detective created by author Raymond Chandler

* Marlowe (name), including list of people and characters w ...

, and visiting Paris with Hilton. Auden would become a lifelong friend who inspired MacNeice to take up poetry seriously.

In 1928 he was introduced to the Classics don John Beazley

Sir John Davidson Beazley, (; 13 September 1885 – 6 May 1970) was a British classical archaeologist and art historian, known for his classification of Attic vases by artistic style. He was Professor of Classical Archaeology and Art at the Un ...

and his stepdaughter Mary Ezra. A year later he thought to soften the news that he had been arrested for drunkenness by telegraphing his father to say he was engaged to be married to Mary. John MacNeice (by now Archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denominations, above that o ...

of Connor, and a Bishop a few years later) was horrified to discover his son was engaged to a Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

, while Ezra's family demanded assurances that Louis's brother's Down's syndrome

Down syndrome or Down's syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21. It is usually associated with physical growth delays, mild to moderate intellectual disa ...

was not hereditary. Amidst this turmoil MacNeice published four poems in ''Oxford Poetry, 1929'' and his first undergraduate collection ''Blind Fireworks'' (1929). Published by Gollancz, the volume was dedicated to "Giovanna" (Mary's full name was Giovanna Marie Thérèse Babette 908-1991. In 1930 the couple were married at Oxford Register Office

A register office or The General Register Office, much more commonly but erroneously registry office (except in official use), is a British government office where births, deaths, marriages, civil partnership, stillbirths and adoptions in England ...

, neither set of parents attending the ceremony. He was awarded a first-class degree in '' literae humaniores'', and had already gained an appointment as Assistant Lecturer in Classics at the University of Birmingham

, mottoeng = Through efforts to heights

, established = 1825 – Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery1836 – Birmingham Royal School of Medicine and Surgery1843 – Queen's College1875 – Mason Science College1898 – Mason Univers ...

.

Birmingham, 1930–1936

The newlyweds were found lodgings inBirmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

by E. R. Dodds

Eric Robertson Dodds (26 July 1893 – 8 April 1979) was an Irish classics, classical scholar. He was Regius Professor of Greek (Oxford), Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Oxford from 1936 to 1960.

Early life and education

Dodds wa ...

(a Professor of Greek and MacNeice's future literary executor

The literary estate of a deceased author consists mainly of the copyright and other intellectual property rights of published works, including film, translation rights, original manuscripts of published work, unpublished or partially completed wo ...

) and his wife Bet. Bet was a lecturer in the Department of English. The MacNeices lived in a former coachman's cottage in the grounds of a house in Selly Park

Selly Park is a Residential area, residential suburban district in south-west Birmingham, England. The suburb of Selly Park is located between the Bristol Road (A38 road, A38) and the Pershore Road (A441 road, A441).

Toponymy

Selly Park is name ...

belonging to another professor, Philip Sargant Florence

Philip Sargant Florence (25 June 1890 – 29 January 1982) was an American economist who spent most of his life in the United Kingdom.

Life

His wife Lella Secor Florence and their children

Born in Nutley, New Jersey in the United States, he wa ...

. Birmingham was a very different university (and city) from Oxford, MacNeice was not a natural lecturer, and he found it difficult to write poetry. He turned instead to a semi-autobiographical novel, ''Roundabout Way'', which was published in 1932 under the name of Louis Malone as he feared a novel by an academic would not be favourably reviewed. He felt that married life was not helping his poetry: "To write poems expressing doubt or melancholy, an anarchist conception of freedom or nostalgia for the open spaces (and these were the things that I wanted to express), seemed disloyal to Mariette. Instead I was disloyal to myself, wrote a novel which purported to be an idyll of domestic felicity. As we predicted, the novel was not well received."

The local Classical Association included George Augustus Auden

George Augustus Auden (27 August 1872 – 3 May 1957) was an English physician, professor of public health, school medical officer, and writer on archaeological subjects.

Biography

Auden was born at Horninglow, Burton-upon-Trent, the sixth ...

, Professor of Public Health and father of W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

, and by 1932 MacNeice and Auden's Oxford acquaintance had turned into a close friendship. Auden knew many Marxists

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectic ...

, and Blunt had also become a communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

by this time, but MacNeice, although sympathetic to the left, was always sceptical of easy answers and "the armchair reformist". ''The Strings are False'' (written at the time of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

) describes his wish for a change in society and even revolution, but also his intellectual opposition to Marxism and especially the communism embraced by many of his friends.

MacNeice started to write poetry again, and in January 1933 he and Auden led the first edition of Geoffrey Grigson

Geoffrey Edward Harvey Grigson (2 March 1905 – 25 November 1985) was a British poet, writer, editor, critic, exhibition curator, anthologist and naturalist. In the 1930s he was editor of the influential magazine ''New Verse'', and went on to p ...

's magazine ''New Verse''. MacNeice also started sending poems to T. S. Eliot at around this time, and although Eliot did not feel that they merited Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel B ...

publishing a volume of poems, several were published in Eliot's journal ''The Criterion

''The Criterion'' was a British literary magazine published from October 1922 to January 1939. ''The Criterion'' (or the ''Criterion'') was, for most of its run, a quarterly journal, although for a period in 1927–28 it was published monthly. It ...

''. On 15 May 1934, Louis and Mary's son Daniel John MacNeice was born. In September of that year, MacNeice travelled to Dublin with Dodds, who had republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

sympathies, and met William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

. Unsuccessful attempts at playwriting and another novel were followed in September 1935 by ''Poems'', the first of his collections for Faber and Faber, who would remain his publishers. This helped establish MacNeice as one of the new poets of the 1930s.

In November, Mary left MacNeice and their infant son for a Russian-American graduate student called Charles Katzmann who had been staying with the family. MacNeice engaged a nurse to look after Dan, and his sister and stepmother also helped on occasion. In early 1936, Blunt and MacNeice visited Spain, shortly after the election of the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

government. Auden and MacNeice travelled to Iceland in the summer of that year, which resulted in ''Letters from Iceland

''Letters from Iceland'' is a travel book in prose and verse by W. H. Auden and Louis MacNeice, published in 1937.

The book is made up of a series of letters and travel notes by Auden and MacNeice written during their trip to Iceland in 1936 c ...

'', a collection of poems, letters (some in verse) and essays. In October, MacNeice left Birmingham for a lecturing post in the Department of Greek at Bedford College for Women

Bedford College was in York Place after 1874

Bedford College was founded in London in 1849 as the first higher education college for women in the United Kingdom. In 1900, it became a constituent of the University of London

The University o ...

, part of the University of London

The University of London (UoL; abbreviated as Lond or more rarely Londin in post-nominals) is a federal public research university located in London, England, United Kingdom. The university was established by royal charter in 1836 as a degree ...

.

London, 1936–1940

MacNeice was featured in two high-profile collections of modernist poetry of 1936. The ''Faber Book of Modern Verse

The ''Faber Book of Modern Verse'' was a poetry anthology, edited in its first edition by Michael Roberts, and published in 1936 by Faber and Faber. There was a second edition (1951) edited by Anne Ridler, and a third edition (1965) edited by D ...

'', edited by young writer and critic Michael Roberts, printing MacNeice's '"An Eclogue

An eclogue is a poem in a classical style on a pastoral subject. Poems in the genre are sometimes also called bucolics.

Overview

The form of the word ''eclogue'' in contemporary English developed from Middle English , which came from Latin , wh ...

for Christmas", "Sunday Morning", "Perseus", "The Creditor" and "Snow" towards the end of the roughly chronological book.Korte, Schneider and Lethbridge (2000), ''Anthologies of British Poetry: Critical Perspectives from Literary and Cultural Studies'', ''Faber Book of Modern Verse'' (1936). Editions Rodopi B.V. pp. 156–164 In the book, MacNeice is set in amongst others of the new Auden Group

The Auden Group or the Auden Generation is a group of British and Irish writers active in the 1930s that included W. H. Auden, Louis MacNeice, Cecil Day-Lewis, Stephen Spender, Christopher Isherwood, and sometimes Edward Upward and Rex Warner. ...

, presenting a version of modernism in which Eliot is the star. MacNeice and his group were also featured in ''Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892–1935

The ''Oxford Book of Modern Verse 1892–1935'' was a poetry anthology edited by W. B. Yeats, and published in 1936 by Oxford University Press. A long and interesting introductory essay starts from the proposition that the poets included should ...

'', edited by Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

. This collection generally excluded American poets and was less well received critically, but instantaneously became a best-seller.

MacNeice moved into Geoffrey Grigson's former flat in Hampstead

Hampstead () is an area in London, which lies northwest of Charing Cross, and extends from Watling Street, the A5 road (Roman Watling Street) to Hampstead Heath, a large, hilly expanse of parkland. The area forms the northwest part of the Lon ...

with Daniel and his nurse. His translation of Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Greek ...

's ''Agamemnon

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon (; grc-gre, Ἀγαμέμνων ''Agamémnōn'') was a king of Mycenae who commanded the Greeks during the Trojan War. He was the son, or grandson, of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husb ...

'' was published in late 1936, and produced by the Group Theatre. Shortly afterwards his divorce from Mary was finalised. They continued to write frequent affectionate letters to one another, although Mary married Katzmann shortly after the divorce.

MacNeice started an affair with Nancy Coldstream. Nancy was, like her husband Bill

Bill(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

* Banknote, paper cash (especially in the United States)

* Bill (law), a proposed law put before a legislature

* Invoice, commercial document issued by a seller to a buyer

* Bill, a bird or animal's beak

Plac ...

, a painter and a friend of Auden who had introduced the couple to MacNeice while they were in Birmingham. MacNeice and Nancy visited the Hebrides

The Hebrides (; gd, Innse Gall, ; non, Suðreyjar, "southern isles") are an archipelago off the west coast of the Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner and Outer Hebrid ...

in 1937, which resulted in a book of prose and verse written by MacNeice with illustrations by Nancy, ''I Crossed the Minch''.

August 1937 saw the appearance of ''Letters from Iceland'' (which had been finished by the two authors in MacNeice's London home the previous year), and towards the end of the year a play called ''Out of the Picture'' was published and produced by the Group Theatre. Music was written for the production by Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

, as he had done previously for ''Agamemnon''. In 1938, Faber and Faber published a second collection of poems, ''The Earth Compels

''The Earth Compels'' was the second poetry collection by Louis MacNeice. It was published by Faber and Faber on 28 April 1938, and was one of four books by Louis MacNeice to appear in 1938, along with ''I Crossed the Minch'', ''Modern Poetry: A P ...

'', the Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

published ''Modern Poetry'', and Nancy once again contributed illustrations to a book about London Zoo, called simply ''Zoo

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called an animal park or menagerie) is a facility in which animals are kept within enclosures for public exhibition and often bred for conservation purposes.

The term ''zoological garden'' refers to zoo ...

''.

As the year – and his relationship with Nancy – drew to a close, he started work on ''Autumn Journal

''Autumn Journal'' is an autobiographical long poem in twenty-four sections by Louis MacNeice. It was written between August and December 1938, and published as a single volume by Faber and Faber in May 1939. Written in a discursive form, it sets ...

''. By Christmas, Nancy was in love with Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by the ...

's brother Michael, whom she was later to marry, and at the end of the year MacNeice visited Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

shortly before the city fell to Franco

Franco may refer to:

Name

* Franco (name)

* Francisco Franco (1892–1975), Spanish general and dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975

* Franco Luambo (1938–1989), Congolese musician, the "Grand Maître"

Prefix

* Franco, a prefix used when ref ...

. The poem was finished by February 1939, and published in May. It is widely viewed as MacNeice's masterpiece, recording his feelings as the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

raged and the United Kingdom headed towards war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

with Germany, as well as his personal concerns and reflections over the past decade.

During the Easter holiday that year, MacNeice made a brief lecture tour of various American universities, also meeting Mary and Charles Katzmann and giving a reading with Auden and Christopher Isherwood in New York attended by John Berryman

John Allyn McAlpin Berryman (born John Allyn Smith, Jr.; October 25, 1914 – January 7, 1972) was an American poet and scholar. He was a major figure in American poetry in the second half of the 20th century and is considered a key figure in th ...

, and at which Auden met Chester Kallman

Chester Simon Kallman (January 7, 1921 – January 18, 1975) was an American poet, librettist, and translator, best known for collaborating with W. H. Auden on opera librettos for Igor Stravinsky and other composers.

Life

Kallman was born in ...

for the first time. MacNeice also met the writer Eleanor Clark in New York, and arranged to spend the next academic year on sabbatical so that he could be with her. A lectureship at Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

was organised, and in December 1939 MacNeice sailed for America, leaving his son in Ireland. Cornell proved a success but the relationship with Eleanor did not, and MacNeice was back in London by the end of 1940. Faber and Faber published ''Selected Poems'' in March 1940, which contained 20 poems drawn from ''Poems 1935'', ''The Earth Compels'' and ''Autumn Journal''. It went through six impressions by 1945. MacNeice worked as a freelance journalist (he had resigned from his lecturing position at Bedford College while in America) and was awaiting the publication of ''Plant and Phantom'', which was dedicated to Clark (the previous year, the Cuala Press

The Cuala Press was an Irish private press set up in 1908 by Elizabeth Yeats with support from her brother William Butler Yeats that played an important role in the Celtic Revival of the early 20th century. Originally Dun Emer Press, from 1908 un ...

had published ''The Last Ditch'', a limited edition containing some poems that would appear in the new volume). In early 1941, MacNeice was employed by the BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...War and after, 1941–1963

MacNeice's work for the BBC initially involved writing and producing radio programmes intended to build support for the US, and later Russia – cultural programmes emphasising links between the countries rather than outright propaganda. A critical work onW. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

(on which he had been working since the poet's death in 1939) was published early in 1941, as were ''Plant and Phantom'' and ''Poems 1925–1940'' (an American anthology). At the end of the year, MacNeice started a relationship with Hedli Anderson

Antoinette Millicent Hedley Anderson (1907 – 1990) was an English singer and actor.

Known as Hedli Anderson, she studied singing in England and Germany before returning to London in 1934. Anderson joined the Group Theatre, and performed in ca ...

and they were married in July 1942, three months after the death of his father. Brigid Corinna MacNeice (known by her second name like her parents, or as "Bimba") was born a year later. By the end of the war MacNeice had written well over sixty scripts for the BBC and a further collection of poems, ''Springboard''. The radio play ''Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

'', produced in 1942 and later published as a book, featured music by William Walton

Sir William Turner Walton (29 March 19028 March 1983) was an English composer. During a sixty-year career, he wrote music in several classical genres and styles, from film scores to opera. His best-known works include ''Façade'', the cantat ...

, conducted by Adrian Boult, and starred Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

. 1943's ''He Had a Date'' (loosely based on the life and death of MacNeice's friend Graham Shepard

Graham Howard Shepard (1907–20 September 1943) was an English illustrator and cartoonist.

He was the son of Ernest H. Shepard, the illustrator of ''Winnie-the-Pooh'' and ''The Wind in the Willows''. He was educated at Marlborough College and ...

but also semi-autobiographical) was also published, as was '' The Dark Tower'' (1946, again with music by Britten). Dylan Thomas

Dylan Marlais Thomas (27 October 1914 – 9 November 1953) was a Welsh poet and writer whose works include the poems "Do not go gentle into that good night" and "And death shall have no dominion", as well as the "play for voices" ''Under ...

acted in some of MacNeice's plays during this period, and the two poets, both heavy drinkers, also became social companions. MacNeice narrated (and wrote poems for) the 1945 film Painted Boats

''Painted Boats'' (US titles ''The Girl on the Canal'' or ''The Girl of the Canal'') is a black-and-white British film directed by Charles Crichton and released by Ealing Studios in 1945. ''Painted Boats'', one of the lesser-known Ealing films ...

.

In 1947, the BBC sent MacNeice to report on Indian independence and partition

Partition may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Disk partitioning, the division of a hard disk drive

* Memory partition, a subdivision of a computer's memory, usually for use by a single job

Software

* Partition (database), the division of a ...

, and he continued to produce plays for the corporation, including a six-part radio adaptation of Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as treat ...

's ''Faust

Faust is the protagonist of a classic German legend based on the historical Johann Georg Faust ( 1480–1540).

The erudite Faust is highly successful yet dissatisfied with his life, which leads him to make a pact with the Devil at a crossroads ...

'' in 1949. 1948's collection of poems, ''Holes in the Sky'', met with a less favourable reception than previous books. In 1950 he was given eighteen months' leave to become Director of the British Institute in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, run by the British Council

The British Council is a British organisation specialising in international cultural and educational opportunities. It works in over 100 countries: promoting a wider knowledge of the United Kingdom and the English language (and the Welsh lan ...

. Patrick Leigh Fermor

Sir Patrick Michael Leigh Fermor (11 February 1915 – 10 June 2011) was an English writer, scholar, soldier and polyglot. He played a prominent role in the Cretan resistance during the Second World War, and was widely seen as Britain's greates ...

had previously been Deputy Director of the Institute, and he and his future wife, the Honourable Joan Elizabeth Rayner (née Eyres Monsell), became close friends of the MacNeices. ''Ten Burnt Offerings'', poems written in Greece, were broadcast by the BBC in 1951 and published the following year. The family returned to England in August 1951, and Dan (who had been at an English boarding school) left for America in early 1952 to stay with his mother, to avoid national service

National service is the system of voluntary government service, usually military service. Conscription is mandatory national service. The term ''national service'' comes from the United Kingdom's National Service (Armed Forces) Act 1939.

The ...

. Dan would return to England in 1953, but went to live permanently with his mother after a legal battle with MacNeice.

In 1953, MacNeice wrote ''Autumn Sequel'', a long autobiographical poem in terza rima

''Terza rima'' (, also , ; ) is a rhyming verse form, in which the poem, or each poem-section, consists of tercets (three line stanzas) with an interlocking three-line rhyme scheme: The last word of the second line in one tercet provides the rh ...

, which critics compared unfavourably with ''Autumn Journal''. The death of Dylan Thomas came partway through the writing of the poem, and MacNeice involved himself in memorials for the poet and attempts to raise money for his family. 1953 and 1954 brought lecture and performance tours of the USA (husband and wife would present an evening of song, monologue and poetry readings), and meetings with John Berryman

John Allyn McAlpin Berryman (born John Allyn Smith, Jr.; October 25, 1914 – January 7, 1972) was an American poet and scholar. He was a major figure in American poetry in the second half of the 20th century and is considered a key figure in th ...

(on the returning boat in 1953, and later in London) and Eleanor Clark (by now married to Robert Penn Warren

Robert Penn Warren (April 24, 1905 – September 15, 1989) was an American poet, novelist, and literary critic and was one of the founders of New Criticism. He was also a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers. He founded the liter ...

). MacNeice travelled to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

in 1955 and Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

in 1956 on lengthy assignments for the BBC. Another poorly received collection of poems, ''Visitations'', was published in 1957, and the MacNeices bought a holiday home on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

from J. B. Priestley

John Boynton Priestley (; 13 September 1894 – 14 August 1984) was an English novelist, playwright, screenwriter, broadcaster and social commentator.

His Yorkshire background is reflected in much of his fiction, notably in ''The Good Compa ...

(an acquaintance since MacNeice's arrival in London twenty years earlier). However, the marriage was starting to become strained. MacNeice was drinking increasingly heavily, and having more or less serious affairs with other women. At this time MacNeice became increasingly independent of spirit, spending time with other writers, including Dominic Behan

Dominic Behan ( ; ga, Doiminic Ó Beacháin; 22 October 1928 – 3 August 1989) was an Irish songwriter, singer, short story writer, novelist and playwright who wrote in Irish and English. He was also a socialist and an Irish republican. Born i ...

with whom he regularly drank to oblivion; the two men spent a particularly drunken night in the home of Cecil Woodham-Smith during a curious meeting in Ireland whilst Behan was working on assignment as a writer for ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth, reaction to stimuli, metabolism, energ ...

'' magazine and MacNeice on assignment with the BBC. During the trip, which allegedly lasted some weeks, neither writer managed successfully to file their copy.

MacNeice was awarded the

MacNeice was awarded the CBE

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established o ...

in the 1958 New Year's Honours list. A South African trip in 1959 was followed by the start of his final relationship, with the actress Mary Wimbush

Mary Wimbush (19 March 1924 – 31 October 2005) was an English actress whose career spanned 60 years. Active across film, television, theatre and radio, she was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Supporting Actress for the 1969 film ''Oh! ...

, who had performed in his plays since the forties. Hedli asked MacNeice to leave the family home in late 1960. In early 1961, ''Solstices'' was published, and in the middle of the year MacNeice became a half-time employee at the BBC, leaving him six months a year to work on his own projects. By this time he was "living on alcohol", and eating very little, but still writing (including a commissioned work on astrology, which he viewed as "hack-work"). In August 1963 he went caving in Yorkshire to gather sound effects for his final radio play, ''Persons from Porlock''. Caught in a storm on the moors, he did not change out of his wet clothes until he was home in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

. Bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

evolved into viral pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

, and he was admitted to hospital in London on 27 August, dying there on 3 September, aged 55.

His ashes were buried in Carrowdore

Carrowdore () is a small village on the Ards Peninsula in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is situated in the townland of Ballyrawer, the Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish of Donaghadee (civil parish), Donaghadee and the historic Barony (g ...

churchyard in County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 531,665. It borders County Antrim to the ...

, with his mother and maternal grandfather. His final book of poems, ''The Burning Perch'', was published a few days after his funeral – Auden, who gave a reading at MacNeice's memorial service, described the poems of his last two years as "among his very best".

Influence

MacNeice wrote in the introduction to his ''Autumn Journal

''Autumn Journal'' is an autobiographical long poem in twenty-four sections by Louis MacNeice. It was written between August and December 1938, and published as a single volume by Faber and Faber in May 1939. Written in a discursive form, it sets ...

'', "Poetry in my opinion must be honest before anything else and I refuse to be 'objective' or clear-cut at the cost of honesty." He has inspired many poets since his death, particularly those from Northern Ireland such as Paul Muldoon

Paul Muldoon (born 20 June 1951) is an Irish poet. He has published more than thirty collections and won a Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the T. S. Eliot Prize. At Princeton University he is currently both the Howard G. B. Clark '21 University P ...

and Michael Longley

Michael Longley, (born 27 July 1939, Belfast, Northern Ireland), is an Anglo-Irish poet.

Life and career

One of twin boys, Michael Longley was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, to English parents, Longley was educated at the Royal Belfast A ...

. There has been a movement to reclaim him as an Irish writer rather than a satellite of Auden. Longley has edited two selections of his work, and Muldoon gives more space to MacNeice than to any other author in his ''Faber Book of Contemporary Irish Poetry'', which covers the period from the death of W. B. Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

until 1986. Muldoon and Derek Mahon

Derek Mahon (23 November 1941 – 1 October 2020) was an Irish poet. He was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland but lived in a number of cities around the world. At his death it was noted that his, "influence in the Irish poetry community, lit ...

have both written elegies for MacNeice, Mahon's coming after a pilgrimage to the poet's grave in the company of Longley and Seamus Heaney

Seamus Justin Heaney (; 13 April 1939 – 30 August 2013) was an Irish poet, playwright and translator. He received the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature.

in 1965. At the time of MacNeice's death, John Berryman described him as "one of my best friends", and wrote an elegy in ''Dream Song #267''.

Archive

Louis MacNeice's archive was established at theHarry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pur ...

at the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

in 1964, a year after MacNeice's death. The collection, largely coming from MacNeice's sister Elizabeth Nicholson, includes manuscripts of poetic and dramatic works, a large number of books, correspondence, and books from MacNeice's library.

Works

Poetry collections

* ''Blind Fireworks'' (1929, mainly considered by MacNeice to be juvenilia and excluded from the 1949 ''Collected Poems'') * ''Poems'' (1935) * ''Letters from Iceland

''Letters from Iceland'' is a travel book in prose and verse by W. H. Auden and Louis MacNeice, published in 1937.

The book is made up of a series of letters and travel notes by Auden and MacNeice written during their trip to Iceland in 1936 c ...

'' (1937, with W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

, poetry and prose)

* ''The Earth Compels

''The Earth Compels'' was the second poetry collection by Louis MacNeice. It was published by Faber and Faber on 28 April 1938, and was one of four books by Louis MacNeice to appear in 1938, along with ''I Crossed the Minch'', ''Modern Poetry: A P ...

'' (1938)

* ''Autumn Journal

''Autumn Journal'' is an autobiographical long poem in twenty-four sections by Louis MacNeice. It was written between August and December 1938, and published as a single volume by Faber and Faber in May 1939. Written in a discursive form, it sets ...

'' (1939)

* ''The Last Ditch'' (1940)

* ''Selected Poems'' (1940)

* ''Plant and Phantom'' (1941)

* ''Springboard'' (1944)

* ''Prayer Before Birth

"Prayer Before Birth" is a poem written by the Irish poet Louis MacNeice (1907–1963) at the height of the Second World War. Written from the perspective of an unborn child, the poem expresses the author's fear at what the world's tyranny can do ...

'' (1944)

* ''Holes in the Sky'' (1948)

* ''Collected Poems, 1925–1948'' (1949)

* ''Ten Burnt Offerings'' (1952)

* ''Autumn Sequel'' (1954)

* ''Visitations'' (1957)

* ''Solstices'' (1961)

* ''The Burning Perch'' (1963)

* ''Star-gazer'' (1963)

* ''Selected Poems'' (1964, edited by W. H. Auden)

* ''Collected Poems'' (1966, edited by E. R. Dodds)

* ''Selected Poems'' (1988, edited by Michael Longley

Michael Longley, (born 27 July 1939, Belfast, Northern Ireland), is an Anglo-Irish poet.

Life and career

One of twin boys, Michael Longley was born in Belfast, Northern Ireland, to English parents, Longley was educated at the Royal Belfast A ...

, redesigned and republished by Wake Forest University Press, 2009)

* ''Collected Poems ''(2007, edited by Peter McDonald)

Plays

* '' The Agamemnon of Aeschylus'' (1936, translation) * ''Out of the Picture'' (1937) * ''Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

'' (1944, radio) & performed, Brighton Dome

The Brighton Dome is an arts venue in Brighton, England, that contains the Concert Hall, the Corn Exchange and the Studio Theatre (formerly the Pavilion Theatre). All three venues are linked to the rest of the Royal Pavilion Estate by a tunnel t ...

(2002)

* ''He Had a Date'' (1944, radio, not published separately)

* ''The Dark Tower and other radio scripts'' (1947)

* ''Goethe's Faust

''Faust'' is a tragic play in two parts by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, usually known in English as '' Faust, Part One'' and ''Faust, Part Two''. Nearly all of Part One and the majority of Part Two are written in rhymed verse. Although rarely s ...

'' (1949, published 1951, a translation)

* '' The Mad Islands'' 962

Year 962 ( CMLXII) was a common year starting on Wednesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* December – Arab–Byzantine wars – Sack of Aleppo: A Byzantine e ...

''and The Administrator'' 961

Year 961 (Roman numerals, CMLXI) was a common year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* March 6 – Siege of Chandax: Byzantine forces under Nikephoro ...

(1964, radio)

* '' Persons from Porlock'' 963

Year 963 ( CMLXIII) was a common year starting on Thursday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* March 15 – Emperor Romanos II dies at age 25, probably of poison admini ...

''and other plays for radio'' (1969)

* ''One for the Grave: a modern morality play'' 958

Year 958 ( CMLVIII) was a common year starting on Friday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Byzantine Empire

* October / November – Battle of Raban: The Byzantines under John Tzimiskes ...

(1968)

* ''Selected Plays of Louis MacNeice'', ed. Alan Heuser and Peter McDonald (1993)

MacNeice also wrote several plays which were never produced, and many for the BBC which were never published.

Books (fiction)

* ''Roundabout Way'' (1932, as "Louis Malone") * ''The Sixpence That Rolled Away'' (1956, for children)Books (non-fiction)

* ''I Crossed the Minch'' (1938, travel, prose and verse)

* ''Modern Poetry: A Personal Essay'' (1938, criticism)

* ''

* ''I Crossed the Minch'' (1938, travel, prose and verse)

* ''Modern Poetry: A Personal Essay'' (1938, criticism)

* ''Zoo

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called an animal park or menagerie) is a facility in which animals are kept within enclosures for public exhibition and often bred for conservation purposes.

The term ''zoological garden'' refers to zoo ...

'' (1938)

* ''The Poetry of W. B. Yeats'' (1941)

* ''The Strings Are False'' (1941, published 1965, autobiography)

* ''Meet the US Army'' (1943)

* ''Astrology'' (1964)

* ''Varieties of Parable'' (1965, criticism)

* ''Selected Prose of Louis MacNeice'', ed. Alan Heuser (1990)

Notes

* Louis MacNeice, ''Collected Poems'', ed. by Peter McDonald,Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel B ...

, 2007.

* ''Louis MacNeice: Selected Poems'', Longley, Michael (ed. and Introduction), Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel B ...

. ; published in the United States by Wake Forest University Press.

* Louis MacNeice, ''The Strings are False'' (autobiography), Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel B ...

, 1965.

* Jon Stallworthy

Jon Howie Stallworthy, (18 January 1935 – 19 November 2014) was a British literary critic and poet. He was Professor of English at the University of Oxford from 1992 to 2000, and Professor Emeritus in retirement. He was also a Fellow of Wolfs ...

''Louis MacNeice'' Faber and Faber

Faber and Faber Limited, usually abbreviated to Faber, is an independent publishing house in London. Published authors and poets include T. S. Eliot (an early Faber editor and director), W. H. Auden, Margaret Storey, William Golding, Samuel B ...

, 1995.

References

External links

Louis MacNeice Papers

at the

Harry Ransom Center

The Harry Ransom Center (until 1983 the Humanities Research Center) is an archive, library and museum at the University of Texas at Austin, specializing in the collection of literary and cultural artifacts from the Americas and Europe for the pur ...

Local Writing Legends – Louis MacNeice

at bbc.co.uk

Profile at the Poetry Archive

Profile at Poets.org

Profile at Poetry Foundation

MacNeice at portraits at National Portrait Gallery

* Arthur Strain

"Writer's life celebrated"

BBC News, 12 September 2007. Text and audio file.

Louis MacNeice Memorial Programme

BBC Radio, 1963

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

Emory University

Louis MacNeice collection, 1926-1959

{{DEFAULTSORT:MacNeice, Louis 1907 births 1963 deaths Academics of Bedford College, London Academics of the University of Birmingham Alumni of Merton College, Oxford Anglicans from Northern Ireland Classical scholars of the University of Birmingham Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Formalist poets Male poets from Northern Ireland People educated at Marlborough College Prix Italia winners 20th-century British male writers 20th-century Irish poets Translators of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Deaths from pneumonia in England