Louis George Gregory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

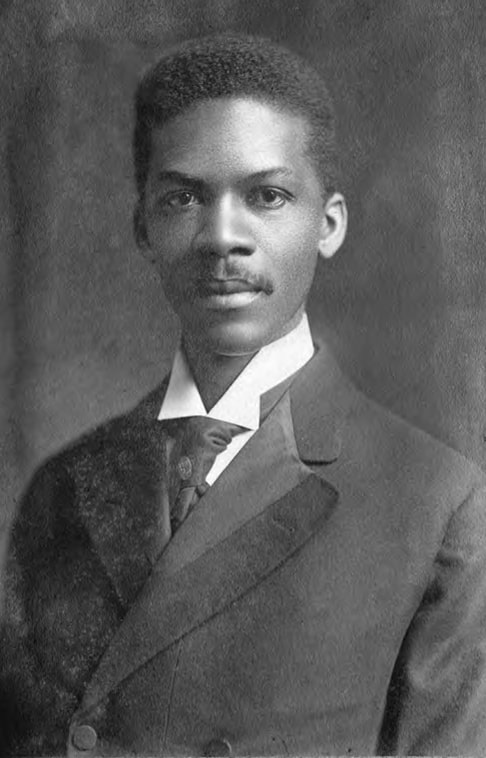

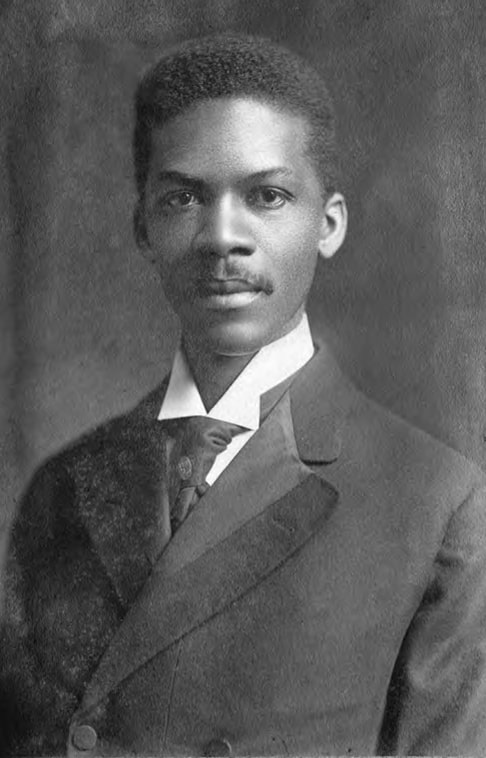

Louis George Gregory (born June 6, 1874, in

Louis George Gregory (born June 6, 1874, in

Mary Elizabeth

George, enslaved

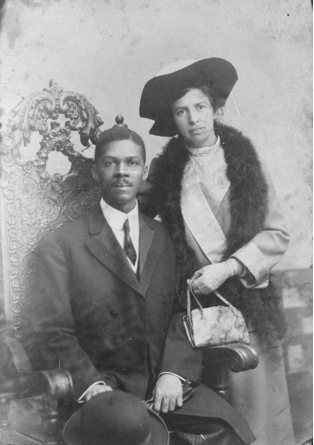

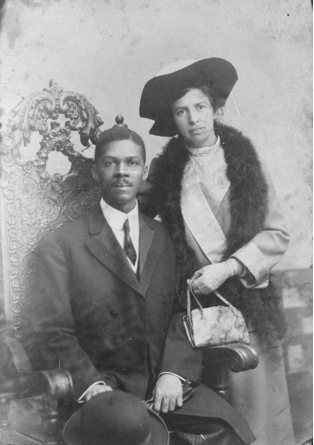

Gregory and Louisa Mathew had deepened their relationship. They married on September 27, 1912, becoming the first known Baháʼí interracial couple.

When Louisa accompanied Gregory during his travels in the United States, they encountered a range of different reactions. Interracial marriage was illegal or unrecognized in a majority of the states at that time.

Gregory and Louisa Mathew had deepened their relationship. They married on September 27, 1912, becoming the first known Baháʼí interracial couple.

When Louisa accompanied Gregory during his travels in the United States, they encountered a range of different reactions. Interracial marriage was illegal or unrecognized in a majority of the states at that time.

Louis Gregory MuseumThe Louis Gregory Project

*Louis Gregory a

Find A GraveMr. Gregory's resting place, Eliot, ME

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gregory, Louis George 1874 births 1951 deaths Hands of the Cause African-American Bahá'ís Fisk University alumni Howard University alumni Converts to the Bahá'í Faith 20th-century Bahá'ís People from Charleston, South Carolina

Louis George Gregory (born June 6, 1874, in

Louis George Gregory (born June 6, 1874, in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

; died July 30, 1951, in Eliot, Maine

Eliot is a town in York County, Maine, United States. Originally settled in 1623, it was formerly a part of Kittery, Maine, to its east. After Kittery, it is the next most southern town in the state of Maine, lying on the Piscataqua River across f ...

) was a prominent American member of the Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the Baháʼí Faith and the unity of religion, essential worth of all religions and Baháʼí Faith and the unity of humanity, the unity of all people. Established by ...

who was devoted to its expansion in the United States and elsewhere. He traveled especially in the South to spread the word about it. In 1922 he was the first African American elected to the nine-member National Spiritual Assembly

Spiritual Assembly is a term given by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to refer to elected councils that govern the Baháʼí Faith. Because the Baháʼí Faith has no clergy, they carry out the affairs of the community. In addition to existing at the local level ...

of the United States and Canada. He was repeatedly re-elected to that position, leading a generation and more of followers. He also worked to prosyletize the faith to Central and South America.

Gregory was posthumously appointed by Shoghi Effendi

Shoghí Effendi (; 1 March 1897 – 4 November 1957) was the grandson and successor of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, appointed to the role of Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith from 1921 until his death in 1957. He created a series of teaching plans that over ...

in 1951 as a Hand of the Cause

Hand of the Cause was a title given to prominent early members of the Baháʼí Faith, appointed for life by the religion's founders. Of the fifty individuals given the title, the last living was ʻAlí-Muhammad Varqá who died in 2007. Hands of ...

, the highest appointed rank in the Baháʼí Faith.

Early years

Louis George was born in Charleston on June 6, 1874, the second son of Ebenezer F. anMary Elizabeth

George, enslaved

African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s who were freed during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. His mother Mary Elizabeth was of mixed race, the daughter of Mary Bacot, an enslaved African, and her white master, eorge Washington Dargan of the Rough Fork plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

in Darlington, South Carolina

Darlington is a city located in Darlington County, South Carolina, United States. In 2010, its population was 6,289. It is the county seat of Darlington County. It is part of the Florence, South Carolina Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Darlington ...

. When Louis was four years old, his father Ebenezer died. He and his mother went to live with his paternal grandfather, a successful blacksmith. When Louis was seven, he witnessed the lynching of his grandfather by whites jealous of his success.

In 1881, Louis's mother remarried to George Gregory, who was the only freeman of African descent to join the Union Army from the 3000 in Charleston at the time. George Gregory rose to 1st Sgt. in the 104th United States Colored Troops

The United States Colored Troops (USCT) were regiments in the United States Army composed primarily of African-American (colored) soldiers, although members of other minority groups also served within the units. They were first recruited during ...

(USCT) after being recruited by Major Delaney, of African descent. After the war, he was honorifically called Colonel Gregory and his family received a Civil War pension. At this point Louis George Gregory took the name of his stepfather. Due to his military service, his stepson Louis George Gregory was introduced in family situations to make friends with the European descent children of Army officers who would visit the home. George Gregory was also a leader in the community, playing a significant role in the inter-racial United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America

The United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, often simply the United Brotherhood of Carpenters (UBC), was formed in 1881 by Peter J. McGuire and Gustav Luebkert. It has become one of the largest trade unions in the United State ...

; upon his death in 1929, the Union put out an advertisement in the Charleston Newspaper asking all Union members to attend, 1000 of both races did make it to Monrovia Union Cemetery, where headstones to George and Mary Elizabeth stand to this day.

During his elementary schooling, Louis Gregory attended the Avery Institute

The Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture is a division of the College of Charleston library system. The center is located on the site of the former Avery Normal Institute in the Harleston village district at 125 Bull Stre ...

, the first public school open to both African American and white children in Charleston. George and Mary Elizabeth wanted children, but she lost many as infants. Mary Elizabeth died in 1891, three months after giving birth; that infant died soon after birth. Gregory's older brother Theodore died the same year. Gregory still graduated from the Avery Institute

The Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture is a division of the College of Charleston library system. The center is located on the site of the former Avery Normal Institute in the Harleston village district at 125 Bull Stre ...

, and gave the graduation speech entitled, "Thou Shalt Not Live For Thyself Alone." Avery Institute honors Gregory by displaying his portrait in their preserved classroom.

Gregory gained a stepbrother, Harrison Gregory, when his stepfather married the widow Lauretta Gregory. Lauretta's husband, Louis Noisette, a Civil War veteran, had died while she was pregnant with Harrison.

The Noisette family became prominent in Charleston after leaving Saint-Domingue. Philippe Stanislas Noisette was the young son of a Nantes

Nantes (, , ; Gallo: or ; ) is a city in Loire-Atlantique on the Loire, from the Atlantic coast. The city is the sixth largest in France, with a population of 314,138 in Nantes proper and a metropolitan area of nearly 1 million inhabita ...

horticulturalist working for the King of France. His father sent him to Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

to send back exotic flowers. While there he married Celestine, who was of African descent. They fled the violence of the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt ...

to Charleston, together with two of Celestine's family members.

Because of the miscegenation laws of South Carolina, Philippe had to declare Celestine a slave in order to have her live with him. They had six children together, who were mixed-race. In 1809 he requested manumission of one of the family members, but the legislature refused it.

One of the two men fathered Benjamin who became enslaved by the Solomon family. Benjamin's children recorded in an 1893 deposition that throughout their enslavement their father made clear to them to remember their last name was Noisette rather than that of their enslaver. Harrison escaped enslavement in 1862 and joined the Union Navy on May 6, 1862, in Port Royal, South Carolina. Benjamin also escaped enslavement in 1862 and went on to the freeman's Camp Barker

Camp may refer to:

Outdoor accommodation and recreation

* Campsite or campground, a recreational outdoor sleeping and eating site

* a temporary settlement for nomads

* Camp, a term used in New England, Northern Ontario and New Brunswick to descri ...

, as it was known then, in Washington DC. Gregory's step-brother's father Louis Noisette remained enslaved until African-American soldiers liberated Charleston in February 1865. He then joined the 33rd USCT Regiment as a drummer to help liberate his mother and sister who remained enslaved in Savannah. After the war Louis Noisette married Lauretta, and had the child Harrison Noisette who became Harrison Gregory.

University and professional years

Gregory's generous stepfather paid for his first year atFisk University

Fisk University is a private historically black liberal arts college in Nashville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1866 and its campus is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1930, Fisk was the first Africa ...

in Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the List of muni ...

, where he studied English literature. Using the tailoring skills his mother had taught him he managed the finances needed for the rest of his bachelor's degree. There being no law schools that would accept him in the South, he continued on to Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is classified among "R2: Doctoral Universities – High research activity" and accredited by the Middle States Commissi ...

in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, one of the few universities to accept black graduate students

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by post-secondary students who have earned an undergraduate (bachelor's) degree.

The organization and struc ...

, to study law and received his LL.B

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

degree in Spring 1902. He was admitted to the bar, and along with another young lawyer, James A. Cobb, opened a law office in Washington D.C. The partnership ended in 1906, after Gregory started to work in the United States Department of the Treasury

The Department of the Treasury (USDT) is the national treasury and finance department of the federal government of the United States, where it serves as an executive department. The department oversees the Bureau of Engraving and Printing and t ...

. In 1904 Gregory was listed as a supporter of the committee for a celebration of Booker T. Washington

Booker Taliaferro Washington (April 5, 1856November 14, 1915) was an American educator, author, orator, and adviser to several presidents of the United States. Between 1890 and 1915, Washington was the dominant leader in the African-American c ...

. In 1906 Gregory served as vice president of the Howard University Law School Alumni association. Gregory had been attracted to the Niagara Movement

The Niagara Movement (NM) was a black civil rights organization founded in 1905 by a group of activists—many of whom were among the vanguard of African-American lawyers in the United States—led by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter. ...

and active in the Bethel Literary and Historical Society

The Bethel Literary and Historical Society was an organization founded in 1881 by African Methodist Episcopal Church Bishop Daniel Payne and continued at least until 1915. It represented a highly significant development in African-American society ...

, a Negro organization devoted to discussing issues of the day – he had been elected a vice president in 1907 and president in 1909. Meanwhile, Gregory was visible in the newspapers over racist incidents.

As a Baháʼí

Encountering the religion

At the Treasury Department Gregory met Thomas H. Gibbs, with whom he formed a close relationship. Gibbs, while not being a Baháʼí himself, shared information about the religion to Gregory, and Gregory attended a lecture byLua Getsinger

Louise Aurora Getsinger (1 November 1871, Hume, New York – 2 May 1916, Cairo, Egypt), known as Lua, was one of the first Western members of the Baháʼí Faith, recognized as joining the religion on May 21, 1897, just two years after Thornt ...

, a leading Baháʼí, in 1907. In that meeting he met Pauline Hannen and her husband who invited him to many other meetings through the next couple of years, and Gregory was much affected by the behavior of the Hannens and the religion after having become disillusioned with Christianity. Among the readings Gregory reviewed on the religion was an early edition of The Hidden Words. The meetings were also held among the poor at a school and a Baháʼí view of Christian scripture and prophecy much affected him and presented a framework for a reformulation of society. While the Hannens went on pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

in 1909 to visit ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (; Persian language, Persian: , 23 May 1844 – 28 November 1921), born ʻAbbás ( fa, عباس), was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh and served as head of the Baháʼí Faith from 1892 until 1921. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was later C ...

, then head of the religion, in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, Gregory left the Treasury Department and established his practice in Washington D.C. When the Hannens returned, Gregory once again started attending meetings on the religion and the burgeoning Baháʼí community of DC was holding more and more meetings - particularly integrated meetings of the Hannens and some others. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá also began to communicate either in letters or to those that visited on pilgrimage a preference for integration. On July 23, 1909, Gregory wrote to the Hannens that he was an adherent of the Baháʼí Faith:

It comes to me that I have never taken occasion to thank you specifically for all your kindness and patience, which finally culminated in my acceptance of the great truths of the Baháʼí Revelation. It has given me an entirely new conception of Christianity and of all religion, and with it my whole nature seems changed for the better...It is a sane and practical religion, which meets all the varying needs of life, and I hope I shall ever regard it as a priceless possession.

First actions

At this point, Gregory started organizing meetings for the religion as well, including one under the auspices of theBethel Literary and Historical Society

The Bethel Literary and Historical Society was an organization founded in 1881 by African Methodist Episcopal Church Bishop Daniel Payne and continued at least until 1915. It represented a highly significant development in African-American society ...

, a Negro organization of which he was president previously. He also wrote to ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, who responded to Gregory that he had high expectations of Gregory in the realm of race relations. The Hannens asked that Gregory attend some organizational meetings to help consult on opportunities for the religion. With such meetings the practical aspects of integration with some Baháʼís became crystallized while for others it became a strain they had to work to overcome. Gregory received a letter in November 1909 from ʻAbdu'l-Bahá saying:

I hope that thou mayest become… the means whereby the white and colored people shall close their eyes to racial differences and behold the reality of humanity, that is the universal truth which is the oneness of the kingdom of the human race…. Rely as much as thou canst on the True One, and be thou resigned to the Will of God, so that like unto a candle thou mayest be enkindled in the world of humanity and like unto a star thou mayest shine and gleam from the Horizon of Reality and become the cause of the guidance of both races.In 1910 Gregory stopped working as a lawyer and began a long period of service, holding meetings and traveling for the religion and writing and lecturing on the subject of racial unity. Some initial meetings were held in parallel among the races, but ʻAbdu'l-Bahá made it known that the direction of the community was toward integrated meetings. The fact that upper class white Baháʼís repeatedly achieved steps towards integration was a confirmation to Gregory of the power of the religion. Gregory, still president of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, arranged for presentations by several Baháʼís to the group. Gregory initiated a major trip through the South. He traveled to

Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

; Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city and the county town of County Durham

*County Durham, an English county

*Durham County, North Carolina, a county in North Carolina, United States

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in No ...

and other locations in North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

, the city of his family and childhood; and Macon, Georgia

Macon ( ), officially Macon–Bibb County, is a consolidated city-county in the U.S. state of Georgia. Situated near the fall line of the Ocmulgee River, it is located southeast of Atlanta and lies near the geographic center of the state of Geo ...

, where he told people about the religion. In Charleston he is known to have presented talks at the Carpenter's Union Hall. He contacted a priest who had encountered the religion at Green Acre

Green is the color between cyan and yellow on the visible spectrum. It is evoked by light which has a dominant wavelength of roughly 495570 nm. In subtractive color systems, used in painting and color printing, it is created by a combina ...

in Maine, where he met Mirzá ʻAbu'l-Faḍl. In Charleston Alonzo Twine converted; he was an African-American lawyer and the first known Baháʼí of South Carolina. But Twine was later committed to a mental institution by his mother and family priest, where he died a few years later. He continued to had out Baháʼí pamphlets he had made himself.

Gregory began to participate more in the early Baháʼí administration

The Baháʼí administration or Baháʼí administrative order is the administrative system of the Baháʼí Faith. It has two arms, the #Elected institutions, elected and the #Appointed institutions, appointed. The supreme governing institutio ...

. In February 1911 he was elected to Washington's Working Committee of the Baháʼí Assembly, the first African American to serve in that position. In April 1911 Gregory served as an officer of Harriet Gibbs Marshall's Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression, along with George William Cook of Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is classified among "R2: Doctoral Universities – High research activity" and accredited by the Middle States Commissi ...

and others. The school was advertised, especially in black publications, in several cities across the country.*

•

Pilgrimage

In late 1910 ʻAbdu'l-Bahá invited Gregory to go onpilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

. Gregory sailed from New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

on March 25, 1911. He traveled overland through Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

to Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

and Egypt. In Palestine, Gregory met with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, where he also visited the Shrine of Baháʼu'lláh

The Mansion of Bahjí ( ar, قصر بهجي, Qasr Bahjī, ''mansion of delight'') is a summer house in Acre, Israel where Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, died in 1892. He was buried in an adjacent house, which became the Shri ...

and the Shrine of the Báb

The Shrine of the Báb is a structure on the slopes of Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel, where the remains of the Báb, founder of the Bábí Faith and forerunner of Baháʼu'lláh in the Baháʼí Faith, are buried; it is considered to be the seco ...

. In Egypt he met with Shoghi Effendi

Shoghí Effendi (; 1 March 1897 – 4 November 1957) was the grandson and successor of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, appointed to the role of Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith from 1921 until his death in 1957. He created a series of teaching plans that over ...

. While in the Mideast, he discussed the race issue in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

with ʻAbdu'l-Bahá and the other pilgrims. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá (; Persian language, Persian: , 23 May 1844 – 28 November 1921), born ʻAbbás ( fa, عباس), was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh and served as head of the Baháʼí Faith from 1892 until 1921. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was later C ...

said there was no distinction between the races. During this time, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá started encouraging Gregory and Louisa Mathew, a white English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

pilgrim, to get to know each other.

After leaving Egypt, Gregory traveled to Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, where he spoke at a number of gatherings to Baháʼís and their friends. When he returned to the United States, he continued to travel, mainly in the southern United States to talk about the Baháʼí faith.

He held his first public meeting on the religion after his return, and published an article under his own name in the ''Washington Bee

''The Washington Bee'' was a Washington, D.C.-based American weekly newspaper founded in 1882 and primarily read by African Americans. Throughout almost all of its forty-year history, it was edited by African American lawyer-journalist William Cal ...

'' in November, inspired by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá in Britain that month. He was elected to a Washington Baháʼí working committee.

1912

In April Gregor was elected to the national Baháʼí "executive board". He assisted during ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's visit to the United States, during which he repeatedly emphasized the Baháʼí Faith and the oneness of humanity; he used black-colored references for pictures of beauty and virtue. SeeʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West were a series of trips ʻAbdu'l-Bahá undertook starting at the age of 66, journeying continuously from Palestine to the West between 1910 and 1913. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh, found ...

.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá thanked Gregory's efforts on several occasions. The first was on 23 April 1912 when ʻAbdu'l-Bahá attended several events; first he spoke at Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is classified among "R2: Doctoral Universities – High research activity" and accredited by the Middle States Commissi ...

to over 1000 students, faculty, administrators and visitors — an event commemorated in 2009. He attended a reception by the Persian Charge-de-Affairs and the Turkish Ambassador. At the reception, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá moved the place-cards to seat Gregory, the only African American, at the head table next to him.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá spoke at Bethel Literary and Historical Society

The Bethel Literary and Historical Society was an organization founded in 1881 by African Methodist Episcopal Church Bishop Daniel Payne and continued at least until 1915. It represented a highly significant development in African-American society ...

where Gregory had long been involved and served as president.

Later in June ʻAbdu'l-Bahá addressed the NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E.&nb ...

national convention in Chicago, which was reported by W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American-Ghanaian sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist. Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in ...

in ''The Crisis

''The Crisis'' is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois (editor), Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Mi ...

''.

Gregory and Louisa Mathew had deepened their relationship. They married on September 27, 1912, becoming the first known Baháʼí interracial couple.

When Louisa accompanied Gregory during his travels in the United States, they encountered a range of different reactions. Interracial marriage was illegal or unrecognized in a majority of the states at that time.

Gregory and Louisa Mathew had deepened their relationship. They married on September 27, 1912, becoming the first known Baháʼí interracial couple.

When Louisa accompanied Gregory during his travels in the United States, they encountered a range of different reactions. Interracial marriage was illegal or unrecognized in a majority of the states at that time.

Succeeding years of service

The Washington Baháʼí community struggled to conduct only integrated meetings and establish integrated institutions in Spring 1916. That summer they received ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's earliestTablets of the Divine Plan

The ''Tablets of the Divine Plan'' collectively refers to 14 letters ( tablets) written between March 1916 and March 1917 by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to Baháʼís in the United States and Canada. Included in multiple books, the first five tablets were pr ...

. Joseph Hannen, with whom Gregory worked on a committee, received the Tablet for the South. Republicans had earlier established integrated facilities in the capital for the federal government, but the election of Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

had resulted in his directing segregation in numerous facilities, to satisfy Southerners in his cabinet.

By December Gregory had traveled among 14 of the 16 southern states named, speaking mostly to student audiences, which were overwhelmingly segregated by law. He began a second round in 1917. The NAACP was founding chapters in South Carolina starting in 1918. But since 1915, there had been a revival of the KKK, and there was other social unrest associated with tensions over the Great War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in Europe, which the US entered in 1917. Gregory knew many of the initial organizers of the NAACP.

In 1919, the remaining letters of the ʻAbdu'l-Bahá arrived. He used the example of St. Gregory the Illuminator

Gregory the Illuminator ( Classical hy, Գրիգոր Լուսաւորիչ, reformed: Գրիգոր Լուսավորիչ, ''Grigor Lusavorich'';, ''Gregorios Phoster'' or , ''Gregorios Photistes''; la, Gregorius Armeniae Illuminator, cu, Svyas ...

as a model of effort to spread the religion. Hannen and Gregory were subsequently elected to a committee focused on the American South and Gregory focused on two approaches - presenting the religion's teachings on race issue to social leaders as well as to the general public - and initiated his next more extensive trip from 1919 to 1921 often with Roy Williams, an African-American Baháʼí from New York City. During 1920 a pilgrim returned from seeing ʻAbdu'l-Bahá with a focus on initiating conferences on race issues called "Race Amity Conferences" and Gregory consulted by letter on how to begin. The first one was held May 1921 in Washington DC.

Gregory met Josiah Morse of the University of South Carolina. Starting in the 1930s, several Baháʼís speakers began to appear at university-based events. Gregory developed a friendship with Samuel Chiles Mitchell, president of the University of South Carolina (1909–1913), and shared that ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's views he heard at the Lake Mohonk Conference on International Arbitration affected him in his interracial work into the 1930s.

Gregory also faced increasing opposition. In January 1921 he spoke in Columbia, SC, where some African-American ministers warned against his message and religion. Others invited Gregory to speak to their congregations. One of the ministers who opposed him had assisted in getting the first declared Baháʼí in the state committed to an institution for the mentally insane.

In 1922 Gregory was the first African American to be elected to the National Spiritual Assembly

Spiritual Assembly is a term given by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to refer to elected councils that govern the Baháʼí Faith. Because the Baháʼí Faith has no clergy, they carry out the affairs of the community. In addition to existing at the local level ...

of the United States and Canada, a nine-person body to which he would be repeatedly elected in 1924, 1927, 1932, 1934 and 1946. His correspondence and activities were often covered in local newspapers in the US and beyond.

In 1924 Gregory toured the country to numerous speaking engagements. He often appeared with Alain LeRoy Locke

Alain LeRoy Locke (September 13, 1885 – June 9, 1954) was an American writer, philosopher, educator, and patron of the arts. Distinguished in 1907 as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Locke became known as the philosophical architect ...

, a fellow Baháʼí and prominent African-American thinker of the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

.

Gregory's father died in 1929. He had praised Gregory for his work, marriage, and principles; although he never converted, he also was known to hand out Gregory's pamphlets. An estimated one thousand people attended the funeral, where Gregory read Baháʼí prayers.

In the 1930s Gregory worked in intra- and international developments of the religion. In December 1931 he helped start a Baháʼí study class in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

. He lived in Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the List of muni ...

for several months, where he worked with inquirers from Fisk University

Fisk University is a private historically black liberal arts college in Nashville, Tennessee. It was founded in 1866 and its campus is a historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1930, Fisk was the first Africa ...

. Some helped found that city's first local Spiritual Assembly

Spiritual Assembly is a term given by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to refer to elected councils that govern the Baháʼí Faith. Because the Baháʼí Faith has no clergy, they carry out the affairs of the community. In addition to existing at the local level ...

.

In response to Shoghi Effendi

Shoghí Effendi (; 1 March 1897 – 4 November 1957) was the grandson and successor of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, appointed to the role of Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith from 1921 until his death in 1957. He created a series of teaching plans that over ...

's call for the goals of the Tablets of the Divine Plan

The ''Tablets of the Divine Plan'' collectively refers to 14 letters ( tablets) written between March 1916 and March 1917 by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá to Baháʼís in the United States and Canada. Included in multiple books, the first five tablets were pr ...

, the United States community arranged a program of action. Gregory and his wife Louisa traveled to and lived in Haiti in 1934 promoting the religion. The Haitian government asked them to leave in a matter of months; Catholicism was the dominant established religion.

In 1940 the Atlanta Baháʼí community struggled over integrated meetings. Gregory was among those tasked with resolving the situation in favor of integrated meetings. In early 1942 Gregory spoke at several black schools and colleges in West Virginia, Virginia, and the Carolinas. He also served on the first "assembly development" committee, focused on supporting materials to expand the religion in Central and South America. In 1944 Gregory was on the planning committee for the "All-America Convention", which was attracting attendees from all Baháʼí national communities, both north and south. He wrote the convention report for the ''Baháʼí News

''Baháʼí News'' was a monthly magazine, published between December 1924 and October 1990, that covered "news and events in the worldwide Baháʼí community." The magazine was first published as ''Baháʼí News Letter'' for 40 issues, changin ...

'' national journal. He traveled from the winter of 1944 through 1945 among five southern states.

Newspapers covered the Race Amity conventions organized by Baháʼís from the 1920s through the 1950s, against a backdrop of persistent racial issues and violence in the US.

Later years

In December 1948 Gregory suffered a stroke while returning from a funeral for a friend. His wife's health was also declining and the couple began to stay closer to home. They lived atGreen Acre Baháʼí School

Green Acre Baháʼí School is a conference facility in Eliot, Maine, in the United States, and is one of three leading institutions owned by the Baháʼí Faith in the United States, National Spiritual Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United ...

in Eliot, Maine

Eliot is a town in York County, Maine, United States. Originally settled in 1623, it was formerly a part of Kittery, Maine, to its east. After Kittery, it is the next most southern town in the state of Maine, lying on the Piscataqua River across f ...

. Gregory carried on correspondence with U.S. District Court Judge Julius Waties Waring

Julius Waties Waring (July 27, 1880 – January 11, 1968) was a United States federal judge, United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina who played an important role in the early leg ...

and his wife in 1950-1; Waring was involved in ''Briggs v. Elliott

''Briggs v. Elliott'', 342 U.S. 350 (1952), on appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of South Carolina, challenged school segregation in Summerton, South Carolina. It was the first of the five cases combined into ''Brown v ...

''.

Gregory died aged seventy-seven on July 30, 1951. He is buried at a cemetery near the Green Acre Baháʼí school. His wife Louisa sought comfort with the Noisette family in New York after his passing.

Legacy and honors

*On his death,Shoghi Effendi

Shoghí Effendi (; 1 March 1897 – 4 November 1957) was the grandson and successor of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, appointed to the role of Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith from 1921 until his death in 1957. He created a series of teaching plans that over ...

, then head of the religion, cabled to the American Baháʼí community:

Profoundly deplore grievous loss of dearly beloved, noble-minded, golden-hearted Louis Gregory, pride and example to the Negro adherents of the Faith. Keenly feel loss of one so loved, admired and trusted by ʻAbdu'l-Bahá. Deserves rank of first*Gregory was amongHand of the Cause Hand of the Cause was a title given to prominent early members of the Baháʼí Faith, appointed for life by the religion's founders. Of the fifty individuals given the title, the last living was ʻAlí-Muhammad Varqá who died in 2007. Hands of ...of his race. Rising Baháʼí generation in African continent will glory in his memory and emulate his example. Advise hold memorial gathering in Temple in token recognition of his unique position, outstanding services.

Shoghi Effendi

Shoghí Effendi (; 1 March 1897 – 4 November 1957) was the grandson and successor of ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, appointed to the role of Guardian of the Baháʼí Faith from 1921 until his death in 1957. He created a series of teaching plans that over ...

's first round of appointees to the distinguished rank named Hands of the Cause

Hand of the Cause was a title given to prominent early members of the Baháʼí Faith, appointed for life by the religion's founders. Of the fifty individuals given the title, the last living was ʻAlí-Muhammad Varqá who died in 2007. Hands of ...

. Memorial observances of Gregory's death were among the first events of the newly arrived Baháʼís and first converts in Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territor ...

.

*The Baháʼí radio

Since 1977, the international community of the Baháʼí Faith has established several radio stations worldwide, particularly in the Americas. Programmes may include local news, music, topics related to socio-economic and community development, ed ...

station WLGI is named after Gregory: the ''Louis Gregory Institute''.

*The Louis Gregory Preschool in Lesotho Africa is named for him.

*The Louis G. Gregory Bahá'í Museum in Charleston South Carolina is a memorial to the life and work of its namesake.

Notes

Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

Louis Gregory Museum

*Louis Gregory a

Find A Grave

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gregory, Louis George 1874 births 1951 deaths Hands of the Cause African-American Bahá'ís Fisk University alumni Howard University alumni Converts to the Bahá'í Faith 20th-century Bahá'ís People from Charleston, South Carolina