Long's Expedition of 1820 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Stephen H. Long Expedition of 1820 traversed America's Great Plains and up to the foothills of the

The Stephen H. Long Expedition of 1820 traversed America's Great Plains and up to the foothills of the

The Stephen H. Long Expedition of 1820 traversed America's Great Plains and up to the foothills of the

The Stephen H. Long Expedition of 1820 traversed America's Great Plains and up to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

. It was the first scientific party hired by the United States government to explore the West. Lewis and Clark (1803–1806) and Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

(1805–1807) explored the western frontier but they were primarily military expeditions. A group of scientists traveled to St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

(present Missouri) and on to Council Bluff (Nebraska) for the Yellowstone expedition of the upper Missouri River that would have established a number of military posts. The expensive effort was cancelled following a financial crash, steamboat failures, operational scandals, and negotiation of the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819, which changed the border between New Spain and the United States. The scientists were reassigned to an expedition led by Stephen Harriman Long

Stephen Harriman Long (December 30, 1784 – September 4, 1864) was an American army civil engineer, explorer, and inventor. As an inventor, he is noted for his developments in the design of steam locomotives. He was also one of the most pro ...

. From June 6 to September 13, 1820, Long and fellow scientists traveled across the Great Plains beginning at the Missouri River near present Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest cit ...

, along the Platte River

The Platte River () is a major river in the State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which itsel ...

to the Front Range

The Front Range is a mountain range of the Southern Rocky Mountains of North America located in the central portion of the U.S. State of Colorado, and southeastern portion of the U.S. State of Wyoming. It is the first mountain range encountered ...

, and east along the Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

and Canadian River

The Canadian River is the longest tributary of the Arkansas River in the United States. It is about long, starting in Colorado and traveling through New Mexico, the Texas Panhandle, and Oklahoma. The drainage area is about .Fort Smith in Arkansas. They recorded many new species of plants, insects, and animals. Long termed the land the

The military and scientific expedition planned to travel up the river by steamboat and collect scientific information of the northwest. In the spring of 1819, Long and his scientists began their journey from

The military and scientific expedition planned to travel up the river by steamboat and collect scientific information of the northwest. In the spring of 1819, Long and his scientists began their journey from  The funding for the Yellowstone expedition was withdrawn for a number of reasons. There had been operational scandals and steamboat failures of the expedition. There were also Congressional budget cuts due to the financial crash following the

The funding for the Yellowstone expedition was withdrawn for a number of reasons. There had been operational scandals and steamboat failures of the expedition. There were also Congressional budget cuts due to the financial crash following the  Rather than a string of military posts, the Congressional budget only allowed for one outpost, Fort Atkinson, which was established at the site of Atkinson's winter quarters along the Missouri River. The lean budget meant that the party did not have the men, horses, food, and equipment required for a journey of this scope and length of time. They were warned by white and Native American people against the trip because they would be passing through dry, barren lands, with inadequate supplies, and subject to hostile native tribes.

Rather than a string of military posts, the Congressional budget only allowed for one outpost, Fort Atkinson, which was established at the site of Atkinson's winter quarters along the Missouri River. The lean budget meant that the party did not have the men, horses, food, and equipment required for a journey of this scope and length of time. They were warned by white and Native American people against the trip because they would be passing through dry, barren lands, with inadequate supplies, and subject to hostile native tribes.

Great American Desert

The term Great American Desert was used in the 19th century to describe the part of North America east of the Rocky Mountains to about the 100th meridian. It can be traced to Stephen H. Long's 1820 scientific expedition which put the Great Am ...

.

Background and preparation

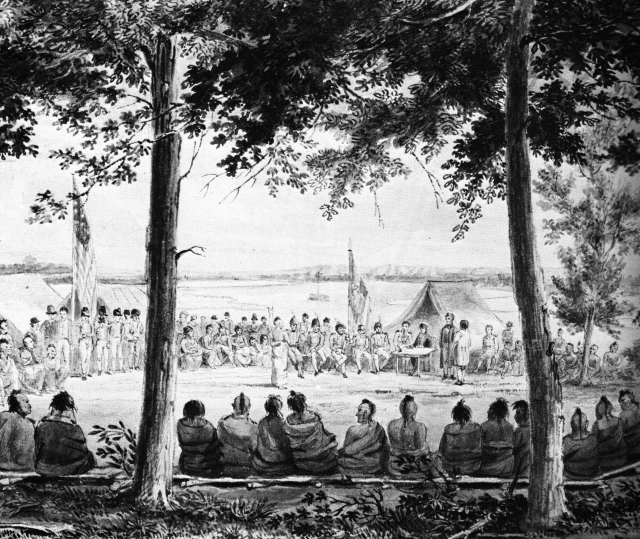

By 1818, British traders operated in the northern Great Plains. The Yellowstone expedition, authorized by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun, was a "grandiose" plan to build a number of military outposts along the upper Missouri River. Colonel Henry Atkinson commanded more than 1100 soldiers of the Sixth Infantry Regiment and the Rifle Regiment to carry out the orders to establish the military posts. The military and scientific expedition planned to travel up the river by steamboat and collect scientific information of the northwest. In the spring of 1819, Long and his scientists began their journey from

The military and scientific expedition planned to travel up the river by steamboat and collect scientific information of the northwest. In the spring of 1819, Long and his scientists began their journey from Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania, the second-most populous city in Pennsylva ...

, Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

on the ''Western Engineer

The paddle steamer ''Western Engineer'' was the first steamboat on the Missouri River. It was purpose built after a design by Major Stephen Harriman Long by the Allegheny Arsenal in Pittsburgh, for the scientific party of the Yellowstone expedi ...

'' that Long designed for the expedition. They traveled along the Ohio River and Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

, and arrived at St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

on June 9, 1819. From there, they made their way along the Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and Missouri Rivers, headed for the Council Bluff area of present Nebraska. Dr. William Baldwin

William Joseph Baldwin (born February 21, 1963), Note: While birthplace is routinely listed as Massapequa, that town has no hospital, and brother Alec Baldwin was born in nearby Amityville, which does. known also as Billy Baldwin,is an American ...

, assigned the roles of botanist and surgeon, became quite ill with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, i ...

. He left the expedition at Franklin, Missouri

Franklin is a city in Howard County, Missouri, United States. It is located along the Missouri River in the central part of the state. Located in a rural area, the city had a population of 70 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Columbia, Miss ...

on July 18, and died on August 31, 1819. Continuing on the Missouri River, the scientists occasionally left the boat to find and document flora and fauna. They reached Council Bluff on September 19, the first steam boat to travel that far up the Missouri River. They set up the Engineer Cantonment

Engineer Cantonment is an archaeological site in Washington County, in the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. Located in the floodplain of the Missouri River near present-day Omaha, Nebraska, it was the temporary winter camp of ...

, staying there throughout the winter. The Sixth Infantry Regiment camped nearby at the Cantonment Missouri.

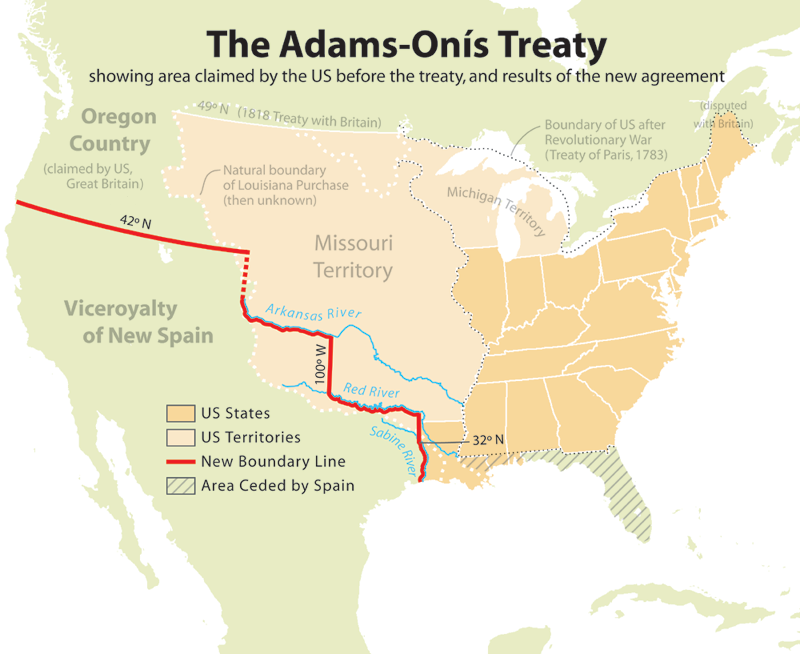

The funding for the Yellowstone expedition was withdrawn for a number of reasons. There had been operational scandals and steamboat failures of the expedition. There were also Congressional budget cuts due to the financial crash following the

The funding for the Yellowstone expedition was withdrawn for a number of reasons. There had been operational scandals and steamboat failures of the expedition. There were also Congressional budget cuts due to the financial crash following the Panic of 1819

The Panic of 1819 was the first widespread and durable financial crisis in the United States that slowed westward expansion in the Cotton Belt and was followed by a general collapse of the American economy that persisted through 1821. The Panic ...

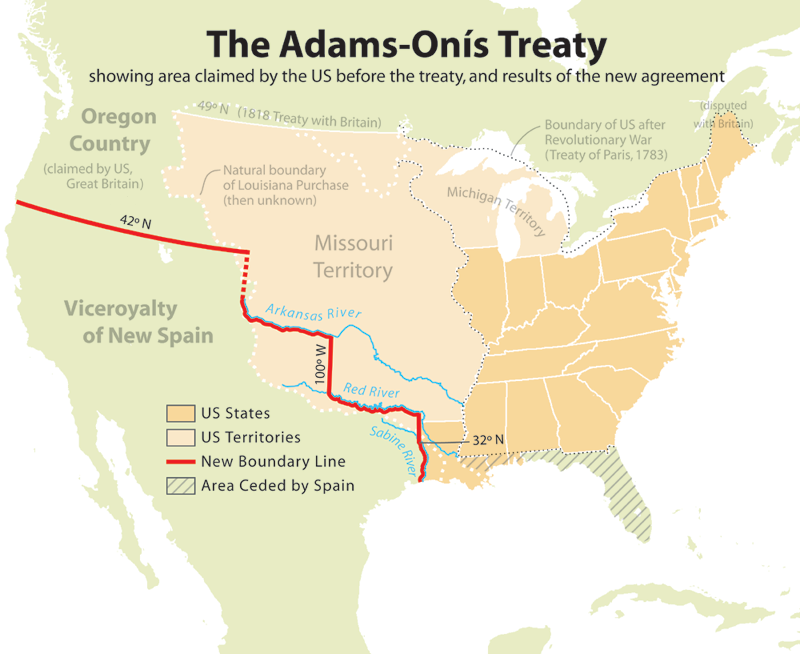

. Another key factor was that the United States and Spain had just completed the Adams–Onís Treaty that made a new United States border to the Pacific Ocean. President James Madison decided that it was now more important to understand the route along the Platte River to the Rocky Mountains and south to the Spanish colonies

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

bordered by the Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

and Red Rivers.

While Congress no longer funded the Yellowstone expedition, it did provide funding for a scaled-down scientific exploration of the Great Plains by Major Stephen Harriman Long

Stephen Harriman Long (December 30, 1784 – September 4, 1864) was an American army civil engineer, explorer, and inventor. As an inventor, he is noted for his developments in the design of steam locomotives. He was also one of the most pro ...

. The scientists that were assigned to the Yellowstone expedition were reassigned to the Long expedition of the Great Plains.

Rather than a string of military posts, the Congressional budget only allowed for one outpost, Fort Atkinson, which was established at the site of Atkinson's winter quarters along the Missouri River. The lean budget meant that the party did not have the men, horses, food, and equipment required for a journey of this scope and length of time. They were warned by white and Native American people against the trip because they would be passing through dry, barren lands, with inadequate supplies, and subject to hostile native tribes.

Rather than a string of military posts, the Congressional budget only allowed for one outpost, Fort Atkinson, which was established at the site of Atkinson's winter quarters along the Missouri River. The lean budget meant that the party did not have the men, horses, food, and equipment required for a journey of this scope and length of time. They were warned by white and Native American people against the trip because they would be passing through dry, barren lands, with inadequate supplies, and subject to hostile native tribes.

Expedition

Objective

The expedition, which occurred from June through September 1820, began along the Missouri River inNebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the sout ...

, traversed through the Plains to the Front Range

The Front Range is a mountain range of the Southern Rocky Mountains of North America located in the central portion of the U.S. State of Colorado, and southeastern portion of the U.S. State of Wyoming. It is the first mountain range encountered ...

of present-day Colorado, southeast along the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

and Canadian River

The Canadian River is the longest tributary of the Arkansas River in the United States. It is about long, starting in Colorado and traveling through New Mexico, the Texas Panhandle, and Oklahoma. The drainage area is about .Oklahoma. The expedition's objective was to travel along the

Long reported that the plains were a

Long reported that the plains were a

200th Anniversary Long Expedition Video

The Garden of the Gods, Colorado Springs {{Authority control 1820 in the United States Botanical expeditions Military expeditions of the United States Exploration of North America American explorers North American expeditions Missouri River Arkansas River Pikes Peak History of United States expansionism

Platte River

The Platte River () is a major river in the State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which itsel ...

to its source, and then travel east along the Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

and Red Rivers to the Mississippi. The scientists were tasked to document the natural resources and the Native Americans, and to map the area that they traversed through the Great Plains. Long said that he wanted all vegetation, land and water life, and geological formations to be studied and documented, along with diseases of animals and insects. "Manners and customs" of Native Americans were to be documented. Illustrations were to capture landscapes "distinguished for their beauty and grandeur".

Expedition team

MajorStephen Harriman Long

Stephen Harriman Long (December 30, 1784 – September 4, 1864) was an American army civil engineer, explorer, and inventor. As an inventor, he is noted for his developments in the design of steam locomotives. He was also one of the most pro ...

, a topographical engineer and scientist with the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

, led the party through the first military and scientific reconnaissance of the Great Plains. Long's scientists had expertise in botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, ethnology

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology). ...

, geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ea ...

, and zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

. Prior to the invention of the permanent photograph, an artist illustrated the landscape.

Long was the group's topographical engineer and cartographer. Lieutenant W. H. Swift was the commanding guard and assistant topographer. Captain John R. Bell was the journalist. Dr. Edwin James was the expedition's physician, botanist and geologist. Titian Peale

Titian Ramsay Peale (November 2, 1799 – March 13, 1885) was an American artist, naturalist, and explorer from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was a scientific illustrator whose paintings and drawings of wildlife are known for their beauty an ...

and Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Georgia, the R ...

were the zoologists. Peale was also an artist. Samuel Seymour was the illustrator.

Corporal Parish and six privates of the Sixth Infantry Regiment, as well as guides and hunters, accompanied Long's expedition. Joseph Bijeau was a Crow language

Crow ( native name: ''Apsáalooke'' ) is a Missouri Valley Siouan language spoken primarily by the Crow Nation in present-day southeastern Montana. The word, ''Apsáalooke,'' translates to "children of the raven." It is one of the larger popul ...

and Native American sign language interpreter. Abram Deloux was a guide and hunter. Stephen Julien was a French and Native American interpreter. D. Adams was a Spanish interpreter. Z. Wilson was the Baggage Master. Duncan and Oakley were engagees. There were eight pack horses and mules, in addition to the horses for each man. The pack animals carried food, camping equipment, rifles, tools necessary for scientific and topographical study, and specimen containers.

Nebraska

Leaving theEngineer Cantonment

Engineer Cantonment is an archaeological site in Washington County, in the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. Located in the floodplain of the Missouri River near present-day Omaha, Nebraska, it was the temporary winter camp of ...

along the Missouri River, the group began their southwestward journey on June 6, 1820. They rose at 5:00 a.m. each morning and covered 20 to 30 miles each day. Riding horseback, Captain Bell led the group of 21 men at a moderate pace. He was followed by the guide, soldiers, and attendants with pack horses. The scientists fell in as they saw fit. Long brought up the rear, managing issues as they arose, ensuring the group stayed together, and ensuring that the cargo remained secure on the pack horses. They made Elkhorn River

The Elkhorn River is a river in northeastern Nebraska, United States, that originates in the eastern Sandhills and is one of the largest tributaries of the Platte River, flowing and joining the Platte just southwest of Omaha, approximately s ...

, a tributary of the Platte River, on June 9 where they met up with French traders bound for an Omaha village to trade goods for fur pelts. One of the men had been recently shot during a Native American attack on the Pratte and Vasquez party. In the early days of their expedition, they passed Pawnee villages and traveled through mostly treeless prairie and were subject to thunderstorms. Near the Loup River

The Loup River (pronounced /lup/) is a tributary of the Platte River, approximately long, in central Nebraska in the United States. The river drains a sparsely populated rural agricultural area on the eastern edge of the Great Plains southeast ...

, they met two Pawnee riding horseback who were bound for a celebration with the Omaha people. They recorded sighting of Bartram's sandpiper, marbled godwit

The marbled godwit (''Limosa fedoa'') is a large migratory shorebird in the family Scolopacidae. On average, it is the largest of the four species of godwit.

Taxonomy

In 1750 the English naturalist George Edwards included an illustration and a ...

s, and other birds and a number of plants, including rabbits foot plaintain and sweet pea

The sweet pea, ''Lathyrus odoratus'', is a flowering plant in the genus ''Lathyrus'' in the family (biology), family Fabaceae (legumes), native plant, native to Sicily, southern Italy and the Aegean Islands.

It is an annual plant, annual climbi ...

s. After crossing Beaver Creek, they met up with three Frenchmen and two Native Americans who were carrying vaccine supplied by the Department of War for the Pawnee. The men had not eaten since they left Missouri and were given some food before they resumed their journey. The expedition camped one night at a Grand Pawnee village.

Since their journey began, they traveled for two weeks on the north side of the Platte River, and across to the South Platte River near present North Platte, Nebraska

North Platte is a city in and the county seat of Lincoln County, Nebraska, United States. It is located in the west-central part of the state, along Interstate 80, at the confluence of the North and South Platte Rivers forming the Platte River. T ...

, where they saw an immense herd of at least 10,000 bison. James collected prairie plants, some recorded for the first time. Peale and Say recorded pronghorn

The pronghorn (, ) (''Antilocapra americana'') is a species of artiodactyl (even-toed, hoofed) mammal indigenous to interior western and central North America. Though not an antelope, it is known colloquially in North America as the American a ...

s, wapiti ( elk), black-tailed jackrabbit

The black-tailed jackrabbit (''Lepus californicus''), also known as the American desert hare, is a common hare of the western United States and Mexico, where it is found at elevations from sea level up to . Reaching a length around , and a ...

, badger

Badgers are short-legged omnivores in the family Mustelidae (which also includes the otters, wolverines, martens, minks, polecats, weasels, and ferrets). Badgers are a polyphyletic rather than a natural taxonomic grouping, being united by ...

s, prairie wolves ( coyote), white-tailed deer

The white-tailed deer (''Odocoileus virginianus''), also known as the whitetail or Virginia deer, is a medium-sized deer native to North America, Central America, and South America as far south as Peru and Bolivia. It has also been introduced t ...

, and prairie dogs. They also found great horned owl

The great horned owl (''Bubo virginianus''), also known as the tiger owl (originally derived from early naturalists' description as the "winged tiger" or "tiger of the air"), or the hoot owl, is a large owl native to the Americas. It is an extre ...

s and golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known birds of ...

s. Traveling southwest, the climate and terrain was more desert-like, with shallow rivers, and bright sunlight that bounced off the sand and hurt their eyes. They passed sites of former Native American villages, but did not see any more Native Americans for more than a month and a half.

Colorado

On June 30, the expeditionary force saw a thin blue line on the horizon. They had their first view of theRocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

near what is now Bijou Creek

Bijou Creek is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed March 25, 2011 tributary of the South Platte River in Colorado. The creek flows northeast from elevated terrain in southe ...

in Fort Morgan. Long named the creek Bijeaus Creek for his guide. Seymour and Peale sketched the mountain range. One peak, higher than the others, was later named Longs Peak

Longs Peak (Arapaho: ) is a high and prominent mountain in the northern Front Range of the Rocky Mountains of North America. The fourteener is located in the Rocky Mountain National Park Wilderness, southwest by south ( bearing 209°) of th ...

for their leader. Following South Platte into Waterton Canyon (Platte Canyon

The Platte Canyon is a deep, narrow, scenic gorge on the South Platte River in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. The canyon is southwest of Denver on the border between Jefferson and Douglas counties. The canyon is at the entrance to the mountai ...

, southwest of present Denver

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Colorado), the men camped for several days to study and record their findings in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. James noted the presence of scrubby oaks, specifically the undescribed Gambel's oak, Say found the first species of solpugids in North America, and a rock wren was collected. A few men decided to follow the South Platte further up the mountains, but they became ill, likely due to altitude sickness

Altitude sickness, the mildest form being acute mountain sickness (AMS), is the harmful effect of high altitude, caused by rapid exposure to low amounts of oxygen at high elevation. People can respond to high altitude in different ways. Sympt ...

. The expedition next headed south towards the Arkansas River, stopping to enjoy the views of what is now Roxborough State Park

Roxborough State Park is a state park of Colorado, United States, known for dramatic red sandstone formations. Located in Douglas County south of Denver, Colorado, the park was established in 1975. In 1980 it was recognized as a National Na ...

. Long took a side journey to the top of Dawson Butte (southwest of Castle Rock, while some of the men traveled along Rampart Range

The Rampart Range is a mountain range in Douglas, El Paso, and Teller counties, Colorado. It is part of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. The range is almost entirely public land within the Pike National Forest

The Pike National Forest ...

, discovering the dusky grouse

The dusky grouse (''Dendragapus obscurus'') is a species of forest-dwelling grouse native to the Rocky Mountains in North America.del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., & Sargatal, J., eds. (1994). ''Handbook of the Birds of the World'' 2: 401-402. Lynx Edi ...

and band-tailed pigeon

The band-tailed pigeon (''Patagioenas fasciata'') is a medium-sized bird of the Americas. Its closest relatives are the Chilean pigeon and the ring-tailed pigeon, which form a clade of ''Patagioenas'' with a terminal tail band and iridescent p ...

.

The group continued to travel south along the Front Range

The Front Range is a mountain range of the Southern Rocky Mountains of North America located in the central portion of the U.S. State of Colorado, and southeastern portion of the U.S. State of Wyoming. It is the first mountain range encountered ...

. Among the new plants that James found was ''aquilegia coerulea

''Aquilegia coerulea'', the Colorado blue columbine, is a species of flowering plant in the buttercup family Ranunculaceae, native to the Rocky Mountains, USA. ''Aquilegia coerulea'' is the state flower of Colorado.

The Latin specific name '' ...

'', the columbine that later became the Colorado state flower. It was found in present day Douglas County near Elephant Rock amongst oak brush land, grassland, and ponderosa pine forest. In addition to other animals that they saw earlier on their trek, they saw kangaroo rat

Kangaroo rats, small mostly nocturnal rodents of genus ''Dipodomys'', are native to arid areas of western North America. The common name derives from their bipedal form. They hop in a manner similar to the much larger kangaroo, but developed t ...

s, a white grizzly bear, robins, and many beaver dams. Bell was inspired to describe it as a place where "naturalists find new inhabitants, the botanist is at a loss which new plant he will first take in hand—the geologist grand subjects for speculation—the geographer & topographer all have subjects for observation."

On July 1, the expedition traveled through Garden of the Gods

Garden of the Gods (Arapaho: ''Ho3o’uu Niitko’usi’i'') is a public park located in Colorado Springs, Colorado, United States. It was designated a National Natural Landmark in 1971.

Name

The area now known as Garden of the Gods was f ...

( Colorado Springs, Colorado) and the foothills of Pikes Peak and nearby mountains and camped along Fountain Creek

Fountain Creek is a stream that originates in Woodland Park in Teller County and flows through El Paso County to its confluence with the Arkansas River near Pueblo in Pueblo County, Colorado. The creek,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydr ...

south of Colorado Springs

Colorado Springs is a home rule municipality in, and the county seat of, El Paso County, Colorado, United States. It is the largest city in El Paso County, with a population of 478,961 at the 2020 United States Census, a 15.02% increase since ...

. It was an area full of wildlife, in addition to other animals that they saw previously, they found wild turkey

The wild turkey (''Meleagris gallopavo'') is an upland ground bird native to North America, one of two extant species of turkey and the heaviest member of the order Galliformes. It is the ancestor to the domestic turkey, which was originally d ...

s, burrowing owl

The burrowing owl (''Athene cunicularia''), also called the shoco, is a small, long-legged owl found throughout open landscapes of North and South America. Burrowing owls can be found in grasslands, rangelands, agricultural areas, deserts, or an ...

s, mule deer

The mule deer (''Odocoileus hemionus'') is a deer indigenous to western North America; it is named for its ears, which are large like those of the mule. Two subspecies of mule deer are grouped into the black-tailed deer.

Unlike the related whi ...

, and a mockingbird

Mockingbirds are a group of New World passerine birds from the family Mimidae. They are best known for the habit of some species mimicking the songs of other birds and the sounds of insects and amphibians, often loudly and in rapid succession. ...

. They lost their supply of fresh water after the creek overflowed during rainstorms, mixing with "historic accumulations of bison dung". Long had been looking for Pikes Peak

Pikes Peak is the highest summit of the southern Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, in North America. The ultra-prominent fourteener is located in Pike National Forest, west of downtown Colorado Springs, Colorado. The town of Manitou S ...

that Zebulon Pike

Zebulon Montgomery Pike (January 5, 1779 – April 27, 1813) was an American brigadier general and explorer for whom Pikes Peak in Colorado was named. As a U.S. Army officer he led two expeditions under authority of President Thomas Jefferson ...

spotted during his expedition. On July 13, James and some others men from the expedition climbed the 14,000-foot mountain peak, the first white person to climb a mountain of that height in North America, according to Richard G. Beidelman. James climbed through alpine

Alpine may refer to any mountainous region. It may also refer to:

Places Europe

* Alps, a European mountain range

** Alpine states, which overlap with the European range

Australia

* Alpine, New South Wales, a Northern Village

* Alpine National Pa ...

fields and high alpine tundra. He saw a pika

A pika ( or ; archaically spelled pica) is a small, mountain-dwelling mammal found in Asia and North America. With short limbs, very round body, an even coat of fur, and no external tail, they resemble their close relative, the rabbit, but wi ...

and "numbers of unknown and interesting plants". At the top of the peak, there was little vegetation, but there were clouds of migratory grasshoppers. The temperature on the summit was 42°, compared to 96° at the main camp. As they headed down the mountain, James realized that the fire from his earlier campsite started a forest fire in the spruce-fir forest. James was concerned that the fire might attract Native Americans. After James's return to the expedition party, the group headed southwest to the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

. The temperature was 100° and the environs were that of semi-arid and barren desert. For 28 miles, they experienced "thirst, heat, and fatigue". Once they found the Arkansas River, some of the party rested. James took a trip up the Arkansas to Royal Gorge

The Royal Gorge is a canyon of the Arkansas River located west of Cañon City, Colorado. The canyon begins at the mouth of Grape Creek, about west of central Cañon City, and continues in a west-northwesterly direction for approximately until ...

(near Cañon City

A canyon (from ; archaic British English spelling: ''cañon''), or gorge, is a deep cleft between escarpments or cliffs resulting from weathering and the erosive activity of a river over geologic time scales. Rivers have a natural tendency to cu ...

). He found it to be "the grandest & most romantic scenery I ever beheld".

They traveled southeast along the Arkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

on July 19. Near La Junta the party divided into two groups on July 24. Bell led a group with zoologist Thomas Say

Thomas Say (June 27, 1787 – October 10, 1834) was an American entomologist, conchologist, and herpetologist. His studies of insects and shells, numerous contributions to scientific journals, and scientific expeditions to Florida, Georgia, the R ...

along the Arkansas River. Three soldiers took Say's trip journal, observations of Native Americans and animals, and Swift's topographical journal and then deserted the expedition.

Oklahoma to Fort Smith, Arkansas

Long led ten men, including botanist Edwin James, south and east into Oklahoma and Texas, they traveled along the Canadian River, mistaking it for the Red River. They met up with a band ofKiowa Apache

The Plains Apache are a small Southern Athabaskan group who live on the Southern Plains of North America, in close association with the linguistically unrelated Kiowa Tribe. Today, they are centered in Southwestern Oklahoma and Northern Texas a ...

s on August 11 and camped with them. It may have been the first recorded contact on the Llano Estacado of Anglo-Americans and Kiowa Apaches. They did not meet up with any other Native American on the rest of the trip.

Having run out of food, the men hunted for deer and buffalo, but there were not sufficient resources that summer to adequately feed them. Therefore, they ate owl, badger, skunk, and horse meat. The climate was difficult—with high temperatures, no shade, and drought—and they often went without water for 24 hours. The water in streams was often undrinkable due to low water levels and the presence of horse manure and sand. They also suffered from biting insects. The two groups of men met up at Fort Smith (Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

) on September 13. During the expedition, the team met up with Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho ba ...

, Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enr ...

, Comanche, and Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

people in Colorado and Oklahoma.

Collection

Over the course of the expedition, the team collected: * More than sixty prepared skins of new or rare animals * Between four and five hundred plants new to the United States * Several thousand insects, hundreds of which were likely new *Terrestrial

Terrestrial refers to things related to land or the planet Earth.

Terrestrial may also refer to:

* Terrestrial animal, an animal that lives on land opposed to living in water, or sometimes an animal that lives on or near the ground, as opposed to ...

and fluviatile shells

* Collections of fossils and minerals

Peale made 122 sketches of animals and other subjects and Seymour made 150 landscapes.

Report

Long reported that the plains were a

Long reported that the plains were a Great American Desert

The term Great American Desert was used in the 19th century to describe the part of North America east of the Rocky Mountains to about the 100th meridian. It can be traced to Stephen H. Long's 1820 scientific expedition which put the Great Am ...

that was not suited for agriculture. By the time that European Americans settled in the Plains, the technology existed for successful deep-well drilling and use of barbed wire. The Long Expedition was carried out during a dry period, which may have influenced the opinion that the land was desert. They would have had better luck finding suitable drinking water if they had traveled up the tributaries that fed into the main rivers.

The scientific and military information about the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the We ...

from Long's expedition was published in scientific journals and books.

See also

* Timeline of the American Old West * Clear Creek, Colorado * Palmer Site, Nebraska *Trapper's Trail

The Trapper's Trail or Trappers' Trail is a north-south path along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains that links the Great Platte River Road at Fort Laramie and the Santa Fe Trail at Bent's Old Fort. Along this path there were a number of ...

, Colorado - used by the expedition

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

200th Anniversary Long Expedition Video

The Garden of the Gods, Colorado Springs {{Authority control 1820 in the United States Botanical expeditions Military expeditions of the United States Exploration of North America American explorers North American expeditions Missouri River Arkansas River Pikes Peak History of United States expansionism