List Of Biophysically Important Macromolecular Crystal Structures on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

1985 -

1985 -  1996 -

1996 -  1998 -

1998 -  2009 - The Vault particle is an intriguing new discovery of a large hollow particle common in cells, with several different suggestions for its possible biological function. The crystal structures (PDB files 2zuo, 2zv4, 2zv5 and 4hl8) show that each half of the vault is made up of 39 copies of a long 12-domain protein that swirl together to form the enclosure. Disorder at the very top and bottom ends suggests openings for possible access to the interior of the vault.

2009 - The Vault particle is an intriguing new discovery of a large hollow particle common in cells, with several different suggestions for its possible biological function. The crystal structures (PDB files 2zuo, 2zv4, 2zv5 and 4hl8) show that each half of the vault is made up of 39 copies of a long 12-domain protein that swirl together to form the enclosure. Disorder at the very top and bottom ends suggests openings for possible access to the interior of the vault.

Crystal structures of protein and nucleic acid molecules and their complexes are central to the practice of most parts of

1960 -

1960 -

effect of factors such as pH and 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate, DPG. For decades hemoglobin was the primary teaching example for the concept of allostery, as well as being an intensive focus of research and discussion on allostery. In 1909, hemoglobin crystals from >100 species were used to relate taxonomy to molecular properties. That book was cited by biophysics

Biophysics is an interdisciplinary science that applies approaches and methods traditionally used in physics to study biological phenomena. Biophysics covers all scales of biological organization, from molecular to organismic and populations. ...

, and have shaped much of what we understand scientifically at the atomic-detail level of biology. Their importance is underlined by the United Nations declaring 2014 as the International Year of Crystallography

The International Year of Crystallography (abbreviation: IYCr2014) is an event promoted in the year 2014 by the United Nations to celebrate the centenary of the discovery of X-ray crystallography and to emphasise the global importance of crystall ...

, as the 100th anniversary of Max von Laue

Max Theodor Felix von Laue (; 9 October 1879 – 24 April 1960) was a German physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1914 for his discovery of the diffraction of X-rays by crystals.

In addition to his scientific endeavors with cont ...

's 1914 Nobel prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

for discovering the diffraction

Diffraction is defined as the interference or bending of waves around the corners of an obstacle or through an aperture into the region of geometrical shadow of the obstacle/aperture. The diffracting object or aperture effectively becomes a s ...

of X-rays by crystals. This chronological list of biophysically notable protein and nucleic acid structures is loosely based on a review in the ''Biophysical Journal

The ''Biophysical Journal'' is a biweekly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Cell Press on behalf of the Biophysical Society. The journal was established in 1960 and covers all aspects of biophysics.

The journal occasionally publishes s ...

''. The list includes all the first dozen distinct structures, those that broke new ground in subject or method, and those that became model systems for work in future biophysical areas of research.

Myoglobin

1960 -

1960 - Myoglobin

Myoglobin (symbol Mb or MB) is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein found in the cardiac and skeletal muscle tissue of vertebrates in general and in almost all mammals. Myoglobin is distantly related to hemoglobin. Compared to hemoglobin, myoglobi ...

was the very first high-resolution crystal structure of a protein molecule. Myoglobin cradles an iron-containing heme

Heme, or haem (pronounced / hi:m/ ), is a precursor to hemoglobin, which is necessary to bind oxygen in the bloodstream. Heme is biosynthesized in both the bone marrow and the liver.

In biochemical terms, heme is a coordination complex "consisti ...

group that reversibly binds oxygen for use in powering muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscl ...

fibers, and those first crystals were of myoglobin from the sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

, whose muscles need copious oxygen storage for deep dives. The myoglobin 3-dimensional structure is made up of 8 alpha-helices

The alpha helix (α-helix) is a common motif in the secondary structure of proteins and is a right hand-helix conformation in which every backbone N−H group hydrogen bonds to the backbone C=O group of the amino acid located four residues ear ...

, and the crystal structure showed that their conformation was right-handed and very closely matched the geometry proposed by Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific top ...

, with 3.6 residues per turn and backbone hydrogen bonds from the peptide NH of one residue to the peptide CO of residue i+4. Myoglobin is a model system for many types of biophysical studies, especially involving the binding process of small ligands such as oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

and carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simple ...

.

Hemoglobin

1960 - TheHemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin BrE) (from the Greek word αἷμα, ''haîma'' 'blood' + Latin ''globus'' 'ball, sphere' + ''-in'') (), abbreviated Hb or Hgb, is the iron-containing oxygen-transport metalloprotein present in red blood cells (erythrocyte ...

crystal structure showed a tetramer of two related chain types and was solved at much lower resolution than the monomeric myoglobin, but it clearly had the same basic 8-helix architecture (now called the "globin fold"). Further hemoglobin crystal structures at higher resolution quaternary_conformation_between_the_oxy_and_deoxy_states_of_hemoglobin,_which_explains_the_cooperativity_of_oxygen_binding_in_the_blood_and_the_allostery.html" "title="Quaternary structure">quaternary conformation between the oxy and deoxy states of hemoglobin, which explains the cooperativity of oxygen binding in the blood and the allostery">allosteric

In biochemistry, allosteric regulation (or allosteric control) is the regulation of an enzyme by binding an effector molecule at a site other than the enzyme's active site.

The site to which the effector binds is termed the ''allosteric site ...Perutz Perutz is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Leo Perutz (1882–1957), Czech-Austrian novelist and mathematician

*Max Ferdinand Perutz (1914–2002), Austrian-British molecular biologist

*Robin Perutz, son of Max, chemist

*Otto Pe ...

in the 1938 report of horse hemoglobin crystals that began his long saga to solve the crystal structure. Hemoglobin crystals are pleochroic

Pleochroism (from Greek πλέων, ''pléōn'', "more" and χρῶμα, ''khrôma'', "color") is an optical phenomenon in which a substance has different colors when observed at different angles, especially with polarized light.

Backgroun ...

- dark red in two directions and pale red in the third - because of the orientation of the hemes, and the bright Soret band Soret may refer to:

Persons

* Charles Soret (1854–1904), a chemist, and son of Jacques-Louis Soret

**Thermophoresis, also known (particularly in liquid mixtures) as the Soret effect, named for him

* Frédéric Soret (1795–1865), a physicist an ...

of the heme porphyrin

Porphyrins ( ) are a group of heterocyclic macrocycle organic compounds, composed of four modified pyrrole subunits interconnected at their α carbon atoms via methine bridges (=CH−). The parent of porphyrin is porphine, a rare chemical com ...

groups is used in spectroscopic analysis of hemoglobin ligand binding.

Hen-egg-white lysozyme

1965 - Hen-egg-whitelysozyme

Lysozyme (EC 3.2.1.17, muramidase, ''N''-acetylmuramide glycanhydrolase; systematic name peptidoglycan ''N''-acetylmuramoylhydrolase) is an antimicrobial enzyme produced by animals that forms part of the innate immune system. It is a glycoside ...

(PDB file 1lyz). was the first crystal structure of an enzyme (it cleaves small carbohydrates

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or may ...

into simple sugars), used for early studies of enzyme mechanism. It contained beta sheet

The beta sheet, (β-sheet) (also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a g ...

(antiparallel) as well as helices, and was also the first macromolecular structure to have its atomic coordinates refined (in real space). The starting material for preparation can be bought at the grocery store, and hen-egg lysozyme crystallizes very readily in many different space groups

In mathematics, physics and chemistry, a space group is the symmetry group of an object in space, usually in three dimensions. The elements of a space group (its symmetry operations) are the rigid transformations of an object that leave it unchan ...

; it is the favorite test case for new crystallographic experiments and instruments. Recent examples are nanocrystals of lysozyme for free-electron laser data collection and microcrystals for micro electron diffraction.

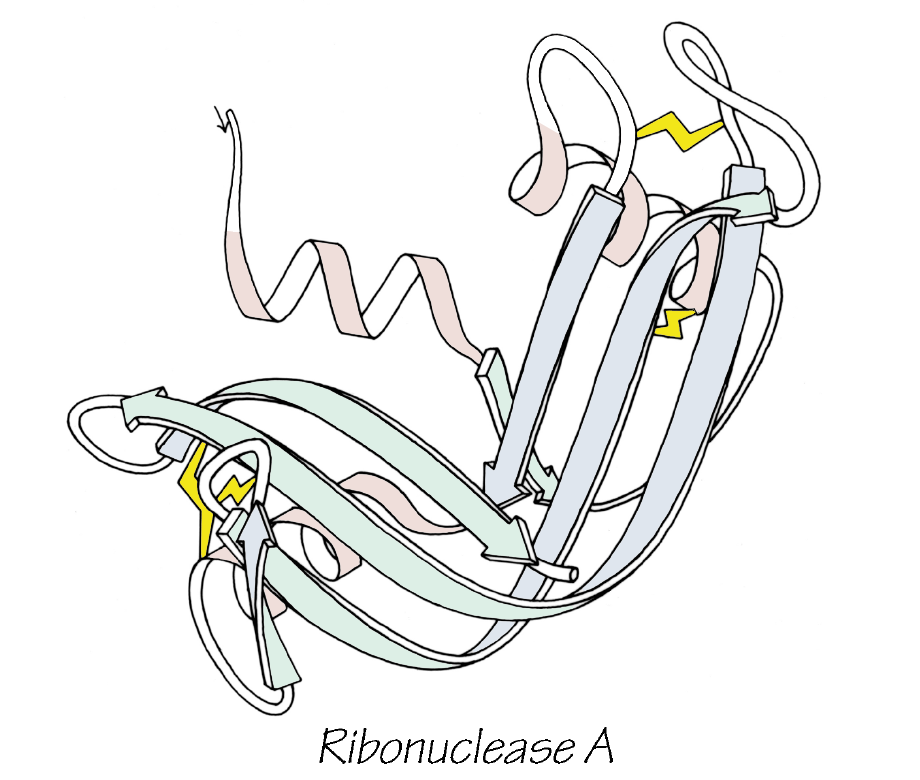

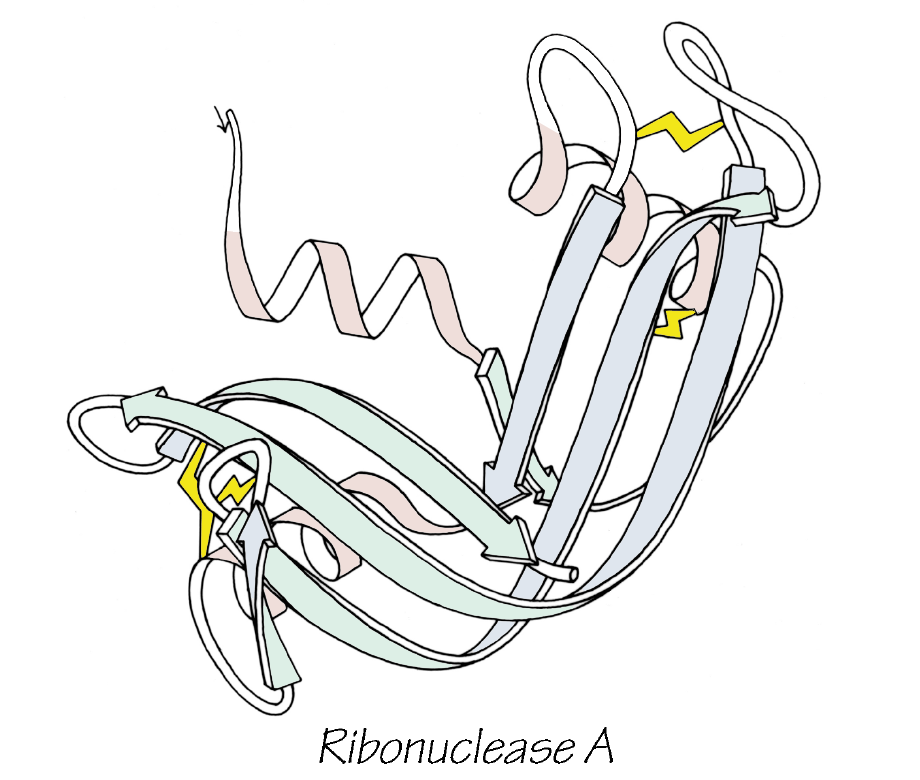

Ribonuclease

1967 -Ribonuclease A

Pancreatic ribonuclease family (, ''RNase'', ''RNase I'', ''RNase A'', ''pancreatic RNase'', ''ribonuclease I'', ''endoribonuclease I'', ''ribonucleic phosphatase'', ''alkaline ribonuclease'', ''ribonuclease'', ''gene S glycoproteins'', ''Ceratit ...

(PDB file 2RSA) is an RNA-cleaving enzyme stabilized by 4 disulfide bonds. It was used in Anfinsen's seminal research on protein folding which led to the concept that a protein's 3-dimensional structure was determined by its amino-acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ami ...

sequence. Ribonuclease S, the cleaved, two-component form studied by Fred Richards, was also enzymatically active, had a nearly identical crystal structure (PDB file 1RNS), and was shown to be catalytically active even in the crystal, helping dispel doubts about the relevance of protein crystal structures to biological function.

Serine proteases

1967 - Theserine proteases

Serine proteases (or serine endopeptidases) are enzymes that cleave peptide bonds in proteins. Serine serves as the nucleophilic amino acid at the (enzyme's) active site.

They are found ubiquitously in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Serin ...

are a historically very important group of enzyme structures, because collectively they illuminated catalytic mechanism (in their case, by the Ser-His-Asp "catalytic triad"), the basis of differing substrate specificities, and the activation mechanism by which a controlled enzymatic cleavage buries the new chain end to properly rearrange the active site. The early crystal structures included chymotrypsin

Chymotrypsin (, chymotrypsins A and B, alpha-chymar ophth, avazyme, chymar, chymotest, enzeon, quimar, quimotrase, alpha-chymar, alpha-chymotrypsin A, alpha-chymotrypsin) is a digestive enzyme component of pancreatic juice acting in the duodenu ...

(PDB file 2CHA), chymotrypsinogen

Chymotrypsinogen is an inactive precursor (zymogen) of chymotrypsin, a digestive enzyme which breaks proteins down into smaller peptides. Chymotrypsinogen is a single polypeptide chain consisting of 245 amino acid residues. It is synthesized in the ...

(PDB file 1CHG), trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the dig ...

(PDB file 1PTN), and elastase

In molecular biology, elastase is an enzyme from the class of ''proteases (peptidases)'' that break down proteins. In particular, it is a serine protease.

Forms and classification

Eight human genes exist for elastase:

Some bacteria (includin ...

(PDB file 1EST). They also were the first protein structures that showed two near-identical domains, presumably related by gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene. ...

. One reason for their wide use as textbook and classroom examples was the insertion-code numbering system (hated by all computer programmers), which made Ser195 and His57 consistent and memorable despite the protein-specific sequence differences.

Papain

1968 -Papain

Papain, also known as papaya proteinase I, is a cysteine protease () enzyme present in papaya (''Carica papaya'') and mountain papaya (''Vasconcellea cundinamarcensis''). It is the namesake member of the papain-like protease family.

It has wide ...

Carboxypeptidase

1969 -Carboxypeptidase A

Carboxypeptidase A usually refers to the pancreatic exopeptidase that hydrolyzes peptide bonds of C-terminal residues with aromatic or aliphatic side-chains. Most scientists in the field now refer to this enzyme as CPA1, and to a related pancrea ...

is a zinc metalloprotease

A metalloproteinase, or metalloprotease, is any protease enzyme whose catalytic mechanism involves a metal. An example is ADAM12 which plays a significant role in the fusion of muscle cells during embryo development, in a process known as myogen ...

. Its crystal structure (PDB file 1CPA) showed the first parallel beta structure: a large, twisted, central sheet of 8 strands with the active-site Zn located at the C-terminal end of the middle strands and the sheet flanked on both sides with alpha helices. It is an exopeptidase

An exopeptidase is any peptidase that catalyzes the cleavage of the terminal (or the penultimate) peptide bond; the process releases a single amino acid, dipeptide or a tripeptide from the peptide chain. Depending on whether the amino acid is rel ...

that cleaves peptides or proteins from the carboxy-terminal end rather than internal to the sequence. Later a small protein inhibitor of carboxypeptidase was solved (PDB file 4CPA) that mechanically stops the catalysis by presenting its C-terminal end just sticking out from between a ring of disulfide bonds with tight structure behind it, preventing the enzyme from sucking in the chain past the first residue.

Subtilisin

1969 -Subtilisin

Subtilisin is a protease (a protein-digesting enzyme) initially obtained from ''Bacillus subtilis''.

Subtilisins belong to subtilases, a group of serine proteases that – like all serine proteases – initiate the nucleophilic attack on the p ...

(PDB file 1sbt ) was a second type of serine protease with a near-identical active site to the trypsin family of enzymes, but with a completely different overall fold. This gave the first view of convergent evolution at the atomic level. Later, an intensive mutational study on subtilisin documented the effects of all 19 other amino acids at each individual position.

Lactate dehydrogenase

1970 -Lactate dehydrogenase

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH or LD) is an enzyme found in nearly all living cells. LDH catalyzes the conversion of lactate to pyruvate and back, as it converts NAD+ to NADH and back. A dehydrogenase is an enzyme that transfers a hydride from on ...

Trypsin inhibitor

1970 - Basic pancreatictrypsin inhibitor A trypsin inhibitor (TI) is a protein and a type of serine protease inhibitor (serpin) that reduces the biological activity of trypsin by controlling the activation and catalytic reactions of proteins. Trypsin is an enzyme involved in the breakdown ...

, or BPTI (PDB file 2pti), is a small, very stable protein that has been a highly productive model system for study of super-tight binding, disulfide bond

In biochemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) refers to a functional group with the structure . The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and is usually derived by the coupling of two thiol groups. In ...

(SS) formation, protein folding

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein chain is translated to its native three-dimensional structure, typically a "folded" conformation by which the protein becomes biologically functional. Via an expeditious and reproduci ...

, molecular stability by amino-acid mutations

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

or hydrogen-deuterium exchange, and fast local dynamics by NMR

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is a physical phenomenon in which nuclei in a strong constant magnetic field are perturbed by a weak oscillating magnetic field (in the near field) and respond by producing an electromagnetic signal with a ...

. Biologically, BPTI binds and inhibits trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting these long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the dig ...

while stored in the pancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an end ...

, allowing activation of protein digestion only after trypsin is released into the stomach.

Rubredoxin

1970 -Rubredoxin

Rubredoxins are a class of low-molecular-weight iron-containing proteins found in sulfur-metabolizing bacteria and archaea. Sometimes rubredoxins are classified as iron-sulfur proteins; however, in contrast to iron-sulfur proteins, rubredoxins do ...

(PDB file 2rxn) was the first redox structure solved, a minimalist protein with the iron bound by 4 Cys sidechains from 2 loops at the top of β hairpins. It diffracted to 1.2Å, enabling the first reciprocal-space refinement

Refinement may refer to: Mathematics

* Equilibrium refinement, the identification of actualized equilibria in game theory

* Refinement of an equivalence relation, in mathematics

** Refinement (topology), the refinement of an open cover in mathem ...

of a protein (4,5rxn). B: beware 4rxn, done without geometry restraints! Archaeal

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archaebact ...

rubredoxins account for many of the highest-resolution small structures in the PDB.

Insulin

1971 -Insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the ''INS'' gene. It is considered to be the main anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabolism o ...

(PDB file 1INS) is a hormone

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones are required ...

central to the metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

of sugar and fat storage, and important in human diseases such as obesity

Obesity is a medical condition, sometimes considered a disease, in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that it may negatively affect health. People are classified as obese when their body mass index (BMI)—a person's we ...

and diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ap ...

. It is biophysically notable for its Zn binding, its equilibrium between monomer, dimer, and hexamer states, its ability to form crystals in vivo, and its synthesis as a longer "pro" form which is then cleaved to fold up as the active 2-chain, SS-linked monomer. Insulin was a success of NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

's crystal-growth program on the Space Shuttle

The Space Shuttle is a retired, partially reusable low Earth orbital spacecraft system operated from 1981 to 2011 by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the Space Shuttle program. Its official program na ...

, producing bulk preparations of very uniform tiny crystals for controlled dosage.

Staphylococcal nuclease

1971 - Staphylococcal nucleaseCytochrome C

1971 -Cytochrome C

The cytochrome complex, or cyt ''c'', is a small hemeprotein found loosely associated with the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. It belongs to the cytochrome c family of proteins and plays a major role in cell apoptosis. Cytochrome c is hig ...

T4 phage lysozyme

1974 - T4 phagelysozyme

Lysozyme (EC 3.2.1.17, muramidase, ''N''-acetylmuramide glycanhydrolase; systematic name peptidoglycan ''N''-acetylmuramoylhydrolase) is an antimicrobial enzyme produced by animals that forms part of the innate immune system. It is a glycoside ...

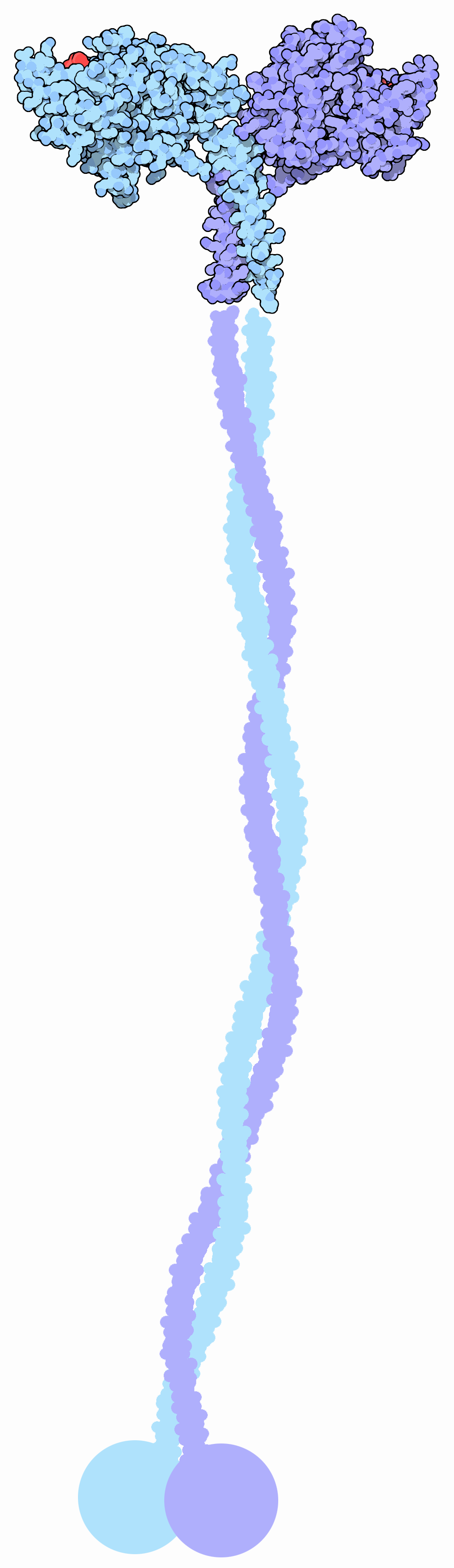

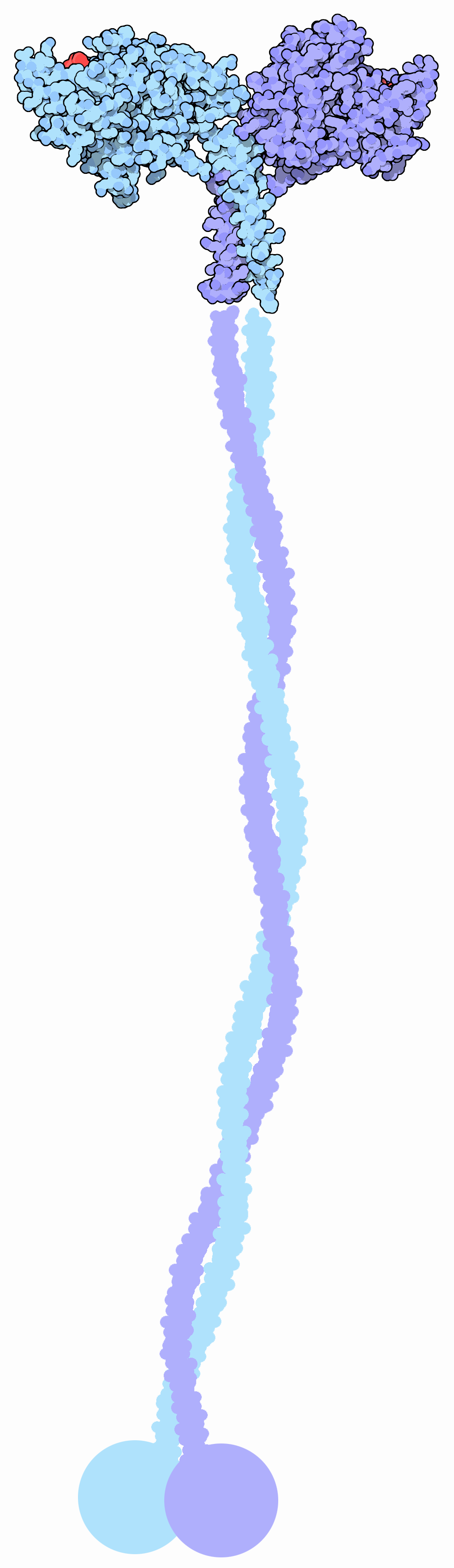

Immunoglobulins

1974 -Immunoglobulin

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

s

Superoxide dismutase

1975 - Cu,ZnSuperoxide dismutase

Superoxide dismutase (SOD, ) is an enzyme that alternately catalyzes the dismutation (or partitioning) of the superoxide () radical into ordinary molecular oxygen (O2) and hydrogen peroxide (). Superoxide is produced as a by-product of oxygen me ...

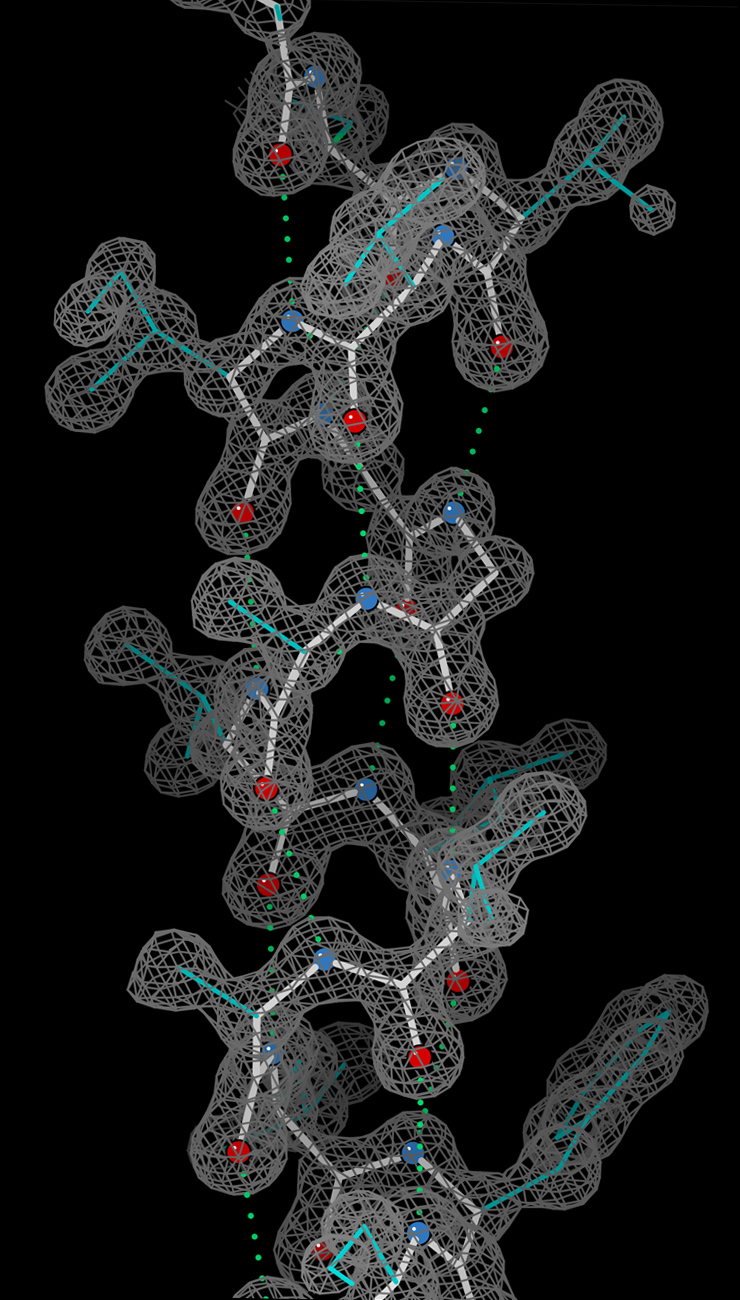

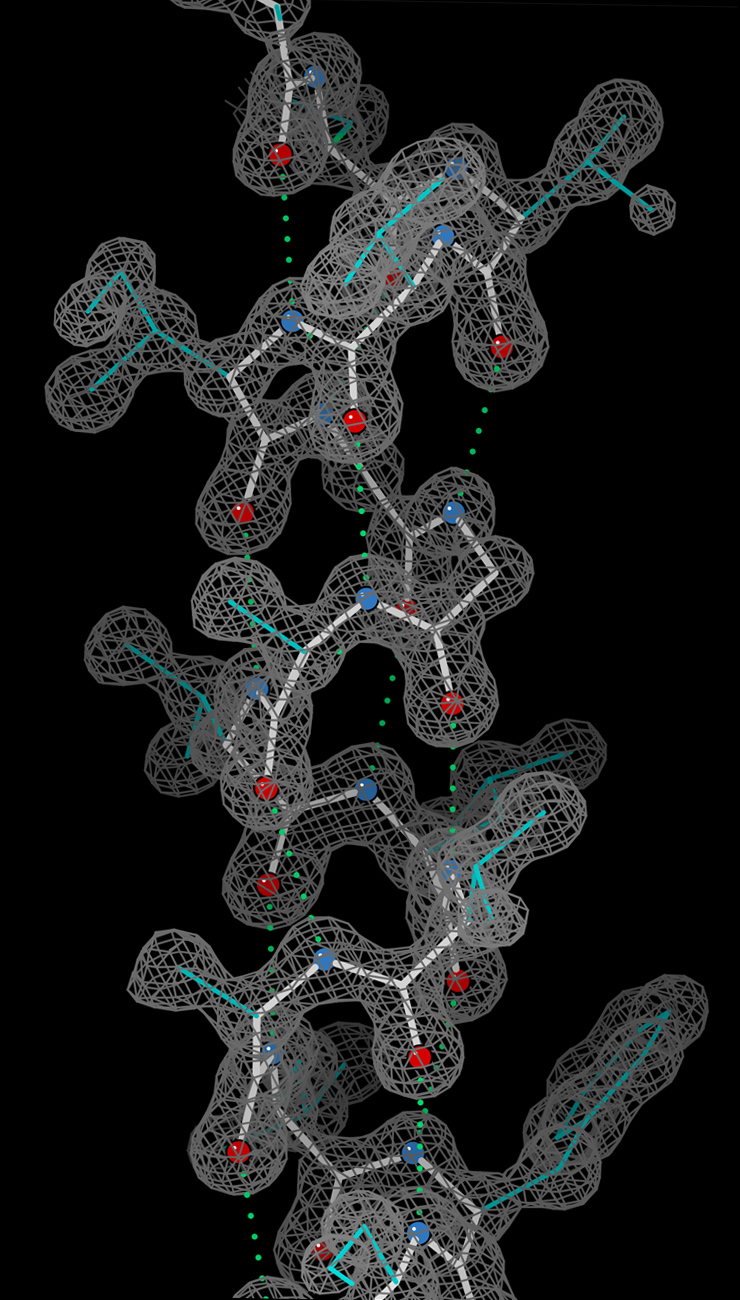

Transfer RNA

1976 -Transfer RNA

Transfer RNA (abbreviated tRNA and formerly referred to as sRNA, for soluble RNA) is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes), that serves as the physical link between the mRNA and the amino ac ...

Triose phosphate isomerase

1976 -Triose phosphate isomerase

Triose-phosphate isomerase (TPI or TIM) is an enzyme () that catalyzes the reversible interconversion of the triose phosphate isomers dihydroxyacetone phosphate and D-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate.

TPI plays an important role in glycolysis and ...

Pepsin-like aspartic proteases

1976 - Rhizopuspepsin 1976 -Endothiapepsin

Endothiapepsin (, ''Endothia aspartic proteinase'', ''Endothia acid proteinase'', ''Endothia parasitica acid proteinase'', ''Endothia parasitica aspartic proteinase'') is an enzyme. This enzyme catalyses the following chemical reaction

: Hydrolys ...

1976 - Penicillopepsin

Later structures (1978 onwards)

1978 - Icosahedralvirus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky's 1 ...

1981 - Dickerson B-form DNA dodecamer

1981 - Crambin

Crambin is a small seed storage protein from the Abyssinian cabbage. It belongs to thionins

Thionins are a family of small proteins found solely in higher plants. Typically, a thionin consists of 45–48 amino acid residues. 6–8 of these are ...

1985 - Calmodulin

Calmodulin (CaM) (an abbreviation for calcium-modulated protein) is a multifunctional intermediate calcium-binding messenger protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells. It is an intracellular target of the secondary messenger Ca2+, and the bind ...

1985 - DNA polymerase

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create ...

1985 -

1985 - Photosynthetic reaction center

A photosynthetic reaction center is a complex of several proteins, pigments and other co-factors that together execute the primary energy conversion reactions of photosynthesis. Molecular excitations, either originating directly from sunlight or t ...

Pairs of bacteriochlorophylls (green) inside the membrane capture energy from sunlight, then traveling by many steps to become available at the heme groups (red) in the cytochrome-C module at the top. This was first crystal structure solved for a membrane protein, a milestone recognized by a Nobel Prize to Hartmut Michel, Hans Deisenhofer, and Robert Huber.

1986 - Repressor/DNA interactions

1987 - Major histocompatibility complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. These cell surface proteins are calle ...

'

1987 - Ubiquitin

Ubiquitin is a small (8.6 kDa) regulatory protein found in most tissues of eukaryotic organisms, i.e., it is found ''ubiquitously''. It was discovered in 1975 by Gideon Goldstein and further characterized throughout the late 1970s and 1980s. Fo ...

1987 - ROP protein

Rop (also known as repressor of primer, or as RNA one modulator (ROM)) is a small dimeric protein responsible for keeping the copy number of ColE1 family and related bacterial plasmids low in '' E. coli'' by increasing the speed of pairing between ...

1989 - HIV-1 protease

HIV-1 protease (PR) is a retroviral aspartyl protease (retropepsin), an enzyme involved with peptide bond hydrolysis in retroviruses, that is essential for the life-cycle of HIV, the retrovirus that causes AIDS. HIV protease cleaves newly synthes ...

1990 - Bacteriorhodopsin

Bacteriorhodopsin is a protein used by Archaea, most notably by haloarchaea, a class of the Euryarchaeota. It acts as a proton pump; that is, it captures light energy and uses it to move protons across the membrane out of the cell. The resulting ...

1991 - GCN4 coiled coil

A coiled coil is a structural motif in proteins in which 2–7

alpha-helices are coiled together like the strands of a rope. (Dimers and trimers are the most common types.) Many coiled coil-type proteins are involved in important biological fun ...

1991 - HIV-1 reverse transcriptase

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to generate complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B to replicate their genomes, ...

1993 - Beta helix of Pectate lyase

1994 - Collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix found in the body's various connective tissues. As the main component of connective tissue, it is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up from 25% to 35% of the whole ...

1994 - Barnase

Barnase (a portmanteau of "BActerial" "RiboNucleASE") is a bacterial protein that consists of 110 amino acids and has ribonuclease activity. It is synthesized and secreted by the bacterium ''Bacillus amyloliquefaciens'', but is lethal to the cell ...

/barstar complex

1994 - F1 ATPase

1995 - Heterotrimeric G proteins

Heterotrimeric G protein, also sometimes referred to as the ''"large" G proteins'' (as opposed to the subclass of smaller, monomeric small GTPases) are membrane-associated G proteins that form a heterotrimeric complex. The biggest non-structura ...

1996 - Green fluorescent protein

The green fluorescent protein (GFP) is a protein that exhibits bright green fluorescence when exposed to light in the blue to ultraviolet range. The label ''GFP'' traditionally refers to the protein first isolated from the jellyfish ''Aequorea ...

1996 - CDK/cyclin

Cyclin is a family of proteins that controls the progression of a cell through the cell cycle by activating cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) enzymes or group of enzymes required for synthesis of cell cycle.

Etymology

Cyclins were originally disco ...

complex

1996 -

1996 - Kinesin

A kinesin is a protein belonging to a class of motor proteins found in eukaryotic cells.

Kinesins move along microtubule (MT) filaments and are powered by the hydrolysis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (thus kinesins are ATPases, a type of enzy ...

motor protein

1997 - GroEL

GroEL is a protein which belongs to the chaperonin family of molecular chaperones, and is found in many bacteria. It is required for the proper folding of many proteins. To function properly, GroEL requires the lid-like cochaperonin protein comp ...

/ES chaperone

1997 - Nucleosome

A nucleosome is the basic structural unit of DNA packaging in eukaryotes. The structure of a nucleosome consists of a segment of DNA wound around eight histone proteins and resembles thread wrapped around a spool. The nucleosome is the fundamen ...

1998 - Group I self-splicing intron

1998 -

1998 - DNA topoisomerase

DNA topoisomerases (or topoisomerases) are enzymes that catalyze changes in the topological state of DNA, interconverting relaxed and supercoiled forms, linked (catenated) and unlinked species, and knotted and unknotted DNA. Topological issues i ...

s perform the biologically important and necessary job of untangling DNA strands or helices that get entwined with each other or twisted too tightly during normal cellular processes such as the transcription

Transcription refers to the process of converting sounds (voice, music etc.) into letters or musical notes, or producing a copy of something in another medium, including:

Genetics

* Transcription (biology), the copying of DNA into RNA, the fir ...

of genetic information.

1998 - Tubulin

Tubulin in molecular biology can refer either to the tubulin protein superfamily of globular proteins, or one of the member proteins of that superfamily. α- and β-tubulins polymerize into microtubules, a major component of the eukaryotic cytoske ...

alpha/beta dimer

1998 - Potassium channel

Potassium channels are the most widely distributed type of ion channel found in virtually all organisms. They form potassium-selective pores that span cell membranes. Potassium channels are found in most cell types and control a wide variety of cel ...

1998 - Holliday junction

A Holliday junction is a branched nucleic acid structure that contains four double-stranded arms joined. These arms may adopt one of several conformations depending on buffer salt concentrations and the sequence of nucleobases closest to the ju ...

2000 - Ribosome

Ribosomes ( ) are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (mRNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules to ...

s are a central part of biology and biophysics, which first became accessible structurally in 2000.

2000 - AAA+ ATPase

2002 - Ankyrin

Ankyrins are a family of proteins that mediate the attachment of integral membrane proteins to the spectrin-actin based membrane cytoskeleton. Ankyrins have binding sites for the beta subunit of spectrin and at least 12 families of integral mem ...

repeats

2003 - TOP7 protein design

Protein design is the rational design of new protein molecules to design novel activity, behavior, or purpose, and to advance basic understanding of protein function. Proteins can be designed from scratch (''de novo'' design) or by making calcula ...

2004 - Cyanobacterial Circadian clock

A circadian clock, or circadian oscillator, is a biochemical oscillator that cycles with a stable phase (waves), phase and is synchronized with solar time.

Such a clock's ''in vivo'' period is necessarily almost exactly 24 hours (the earth's curre ...

proteins

2004 - Riboswitch

In molecular biology, a riboswitch is a regulatory segment of a messenger RNA molecule that binds a small molecule, resulting in a change in production of the proteins encoded by the mRNA. Thus, an mRNA that contains a riboswitch is directly invo ...

2006 - Human exosome

2007 - G-protein-coupled receptor

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as seven-(pass)-transmembrane domain receptors, 7TM receptors, heptahelical receptors, serpentine receptors, and G protein-linked receptors (GPLR), form a large group of evolutionarily-related p ...

2009 - The Vault particle is an intriguing new discovery of a large hollow particle common in cells, with several different suggestions for its possible biological function. The crystal structures (PDB files 2zuo, 2zv4, 2zv5 and 4hl8) show that each half of the vault is made up of 39 copies of a long 12-domain protein that swirl together to form the enclosure. Disorder at the very top and bottom ends suggests openings for possible access to the interior of the vault.

2009 - The Vault particle is an intriguing new discovery of a large hollow particle common in cells, with several different suggestions for its possible biological function. The crystal structures (PDB files 2zuo, 2zv4, 2zv5 and 4hl8) show that each half of the vault is made up of 39 copies of a long 12-domain protein that swirl together to form the enclosure. Disorder at the very top and bottom ends suggests openings for possible access to the interior of the vault.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Biophysically important macromolecular crystal structures Structural biology Macromolecular crystal structures Macromolecular crystal structures Macromolecular crystal structures